Open Journal of Nursing

Vol.3 No.1(2013), Article ID:29551,7 pages DOI:10.4236/ojn.2013.31013

The development of patient education: Experiences of collaborative work between special and primary care in Finland*

![]()

1Oulu University Hospital, Oulu, Finland

2Institute of Health Sciences, University of Oulu, Oulu, Finland

3National Institute for Health and Welfare, Oulu, Finland

Email: #kaija.lipponen@oulu.fi

Received 24 January 2013; revised 28 February 2013; accepted 10 March 2013

Keywords: Patient Education; Collaborative Project; Development Work; Networking; Health Care Staff; Interview Study

ABSTRACT

Evaluating care pathways, strengthening patient education, developing staff’s patient education skills, and improving collaboration between primary and special healthcare workers are all topical challenges. Successful patient education requires seamless cooperation across organizational boundaries throughout the whole nursing process. The aim of this study is to describe participants’ experiences of development work between primary and special health care units on patient education. In this qualitative descriptive study twenty four health care workers who took part in development work in a collaborative project of special and primary health care service in northern Finland were interviewed when they had nine months’ experience of the development work. The material was analysed using content analysis. Experiences of the nature of development work were described using the following categories: attachment to development work, delight in participation, factors supporting success and challenges of development work. Improvement of co-operation between special and primary health service is a topical challenge. Participation in development work offers occupational learning opportunities. Evaluation and development of own work strengthens staff members’ occupational know-how. The results of this research may be utilized in the planning and execution of development work in the field of health care.

1. INTRODUCTION

Changes in the health care system, e.g. an increasing number of outpatients, shortening of nursing hours, development of patient-oriented service processes, management and evaluation of care pathways, as well as recruitment and well-being of staff have posed demands on regional networking and co-operation between special and primary health care [1].

The continuity of care and guidance of patients can be improved by enhancing patient education and by developing support for patients’ self-care and follow-up [2,3]. Evaluation of care chains and development of operation models as well as the strengthening of staff’s guidance skills are primary areas of development in the field of health care [4]. The functionality and productiveness of patient education require seamless co-operation between special and primary health care throughout the whole service process [5,6]. High-quality patient education requires that the care staff have occupational responsibility to maintain and develop their readiness for education work, to promote choices related to the health of the patient and secure a sufficient amount of education [6,7].

In health care organizations, project work is used as a tool for development work and the number of projects as part of the work is expected to increase [4,8]. Development should be included in the basic work of each employee because development work has no power if it is not connected to basic work and if people are not truly committed [9]. Participatory and co-operational development work has positive impacts on the meaningfulness of work and on the quality of care [10,11]. The central elements of maintaining the ability to work and of development work taking place in work communities include employees’ ability to influence their own work, take responsibility and learn new things. Employees want to improve their working skills, be assigned new tasks, face new challenges and find new perspectives on occupational procedures [12,13].

Different staff development interventions have shown positive effects for workers such as a strong rise in job satisfaction [14]. The intervention consisting of education, support and clinical supervision has been discovered to have positive effects on work satisfaction [15]. Participatory organizational intervention carried out by a work team has decreased effort-reward imbalance and absenteeism rates [16]. Team building has also shown to improve job satisfaction of nursing staff [17]. Development of staff’s expertise does not relate simply training the staff, but also to offering the staff different types of opportunities for learning and development [8,10,18]. Evaluation of own work by taking part in development work offers the staff occupational challenges and an opportunity to learn on the job [12,19]. Staff’s contentment with work, occupational growth and development of expertise are beneficial for the organization and for the people using the services [10,18,20,21].

The aim of this study was to describe employees’ experiences of development work in Northern Finland. The research was related to development work that involved regional development of patient education exceeding organizational boundaries. Network development is defined as various ways to promote factors such as skills, knowledge and social support as well as functionality in work units and work processes that cross organization boundaries. Employees from different organizations work in multiprofessional teams, where self-determining, supportive, participative and co-operative strategies are applied. The central part of development work is collaborative learning that involves groups of people working together to solve problems and create new innovations to help their organizations run more smoothly [1].

2. MATERIAL AND METHODS

2.1. Design

The study was undertaken as part of a larger research and development project implemented in Northern Finland in 2006-2008. The development project was carried out as regional co-operation with 14 health centers as well as four hospitals. All the health centers and hospitals were self-selected to the project after meetings between representatives from the municipalities and hospitals. Criteria for inclusion were that the organizations should commit themselves to the entire two-year study period and that the team members could participate in development project during their working hours. Participating organizations signed a written agreement stating that they were committed to the project. Participation was voluntary and based on the interests of the target organizations to be included in the development work on patient education. The objective of the project was to develop the quality of patient education and to increase the efficiency of cooperation between special and primary health care units regionally over organizational boundaries.

In this study, health care staff was seen as a resource to improve the quality of patient education. The regional networking was implemented in self-ruling multiprofessional teams of special and primary health care staff. The practical objective was the modelling of patient education for the service process of six patient groups. Teams were formed according to six patient groups: cardiovascular (17 members), cerebral infarction (14), total joint replacement (12), chronic ulcer (12), cancer (11) and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (5) team. The teams were formed according to these patient groups based on using a lot of services of both special and primary health care units. Each team had members from both primary and special health care units. The members of teams were experts in their own fields, working closely with these patient groups.

The development work included five main elements: regional networking, self-ruling teamwork, collaborative learning, staff education and guidance. In regional networking employees from different organizations worked closely together in multiprofessional teams. Within these teams self-determining, participative and co-operative strategies was applied and members used their own expertise in developmental work for the good of the whole team. In collaborative learning, new knowledge is created within a group where members interact by sharing work experiences. The teams get together once in a month, participated in training sessions and meetings and also make visits in workplaces of each team member. Between the team-meetings the team members were working self-supporting in their workplace or on free time. Team members took part in educational sessions on average two times during the project period. This education was provided to give staff the tools to develop quality of patient education and work processes. Guidance was offered to each team two times including information about the participatory methods of modelling patient education over organizational boundaries. In all teams the nature of development work was the same, that’s why the data will not be analyzed according to patient groups.

2.2. Data Collection

This study consist of interviews (n = 24) with people involved in development work. The interviews were thematic with the following themes: the significance, usefulness and impacts of the development work, and the health staff’s experiences of participating in it. In addition, participants were asked to assess the effect of the development work on their own readiness to undertake patient education (with regard to knowledge, skills, attitude and education methods), information flow and cooperation. Participants were also asked to evaluate the general contribution of the project. The themes were chosen according to the objectives of the development work and they were based on the intuition of the researchers. The questions were not presented using specific words in a certain order: the interview was a discussion on topics chosen in advance. However, the same themes were gone through in each interview. The interviewees also evaluated their experience on participation using school grades from 4 - 10 and with a verbal scale from “going through the motions” to “great”. This article describes the experiences on taking part in development work.

The interviews took place when the teams had nine months’ experience of the development work. The interviewees were recruited discretionarily so that the group included an informant from each team and each occupational group (20 nurses, two physiotherapists, a publichealth nurse and a practical nurse) as well as from every municipality involved in the development work (n = 14). All participants were actively involved in the development work and working within either primary (n = 15) or special (n = 9) healthcare. The age of the participants ranged from 24 to 53 years (mean = 40) and they were working in different stages of the care chain in special (n = 9) or primary (n = 15) health care, and all were women. Two men were involved in this development work but they did not wish to participate in the interviews.

The interview study followed the ethical principles of qualitative research [17]. The researchers contacted the discretionarily chosen team members via secure work e-mail addresses informing them of the purpose of the study and asking if they were interested in participating. The message explained the purpose of the research and the criteria for choosing the interviewees, listed the contact information of the researchers and offered the interviewees an opportunity to take part in the study. The researchers stated that participation in the study was voluntary and that any information they gave would be treated as confidential. Those who agreed to being interviewed contacted the researchers through e-mail or by telephone. Interviews were carried out in the interviewees’ workplace on convenient dates for them. The interview sessions lasted approximately an hour and were recorded. At the start of interviews, the participants were told about the recording procedure and were informed that no-one but the researchers doing the interviews would handle the recordings. Participants were giving a piece of paper outlining the main topics of the theme interview and were emphasized that there were no right or wrong answers. They were also informed that their anonymity would be ensured in the report. Thus, within this paper direct quotations are presented anonymously.

2.3. Data Analysis

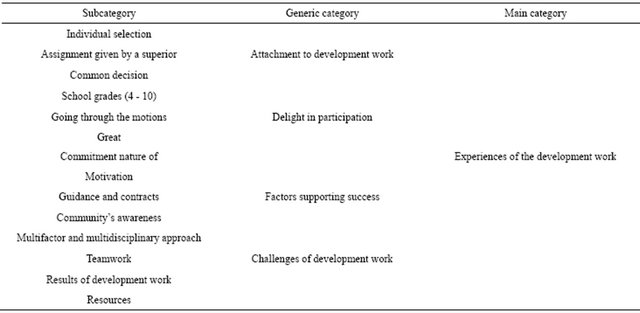

The recorded interviews were transcribed verbatim, and the material was analysed using inductive content analysis [22] by one of the researchers (KL). First, the material (368 text pages) was read through several times. One complete thought from one or a few sentences was chosen as the unit of analysis. The analysis process proceeded from simplifying to grouping and abstracting [22, 23]. All the statements related to a particular theme (for example, participating in development work) were picked out from the material. Then the core meaning of the statements was identified and similar statements were grouped as one category and given a descriptive name (attachment to development work, delight in participation, factors supporting success and challenges of development work). Finally, the researchers identified a single main category covering all the categories and descriptively named it “the nature of development work”. The analysis process is outlined in the Table 1.

3. FINDINGS

Experiences of the nature of development work can be described with four categories: 1) attachment to development work, 2) delight in participation, 3) factors supporting success and 4) challenges of development work (Table 1).

3.1. Attachment to Development Work

The interviewees were chosen to take part in patient education development work based on their individual strengths and their own willingness, or they were assigned by their superiors. Interest in development work and the subject matter, personal characteristics and special know-how formed the base for the individual decisions. Experience and good performance in previous assignments had an impact as well. With individual decisions there was really no common discussion on the issue, but the superior had a clear idea of who might take part. Extensive experience in project work and previous participation in patient education development or patient group related development were considered criteria for selection. Personal characteristics were considered to have an impact on the decision as well.

“I’m very excited about patient education and I was involved in the previous project as well.”

“I have this kind of energy that I always want to do more and do everything better than before.”

Involvement in development work was also perceived as an assignment given by a superior. Superiors made the decision concerning participation and chose the partici-

Table 1. Participants’ experiences of the nature of development work.

pants. The superiors could state their decision without actually asking the employee. There were some cases where superiors forgot to inform the employee about their decision and employees heard about the selection later on from someone else. Professional title, job description and its development were also common factors.

“Our superior informed us about this project and explained that one physiotherapist should participate.”

Attachment to development work was perceived also as a common decision. Some work units considered the matter within the unit before choosing or recruiting employees for the development work. The selected participants were suggested by superiors and chosen jointly. Sometimes the work community’s representative for development work was chosen by lot.

“We had a ward meeting where the project were introduced, and then we decided on how we should get involved. Our head nurse had this idea that I should participate.”

3.2. Delight in Participation

Participation in development work was perceived as a positive experience, although hard, laborious and somewhat unclear in relation to its objectives and requiring tolerance of uncertainty. The school grades (4 - 10) given for the participation by the interviewees varied from good to excellent (8 to 9). One team leader described this as follows: “I would probably grade it 8.5 or 9, so put quite a lot of effort in to this.” Participation had positive and negative sides to it as well as a side that could not be changed. Especially the initiation stage was perceived as quite negative. One nurse described it this way: “At first it felt forced and this was just another project among others.”

At the beginning, the development work was troublesome and time-consuming. The objectives (to develop and modelling patient education) were considered to be too extensive to achieve. The participants did not have a clear idea of how to proceed and sometimes initial excitement turned into lack of enthusiasm. Should teams be successful at development work-that also demands to tolerate uncertainty?

“At first I was afraid of the workload but I turned out to be manageable.”

“I wasn’t sure the project was for me.”

However, the participants were willing to participate in development work again. The experience was positive and participation was perceived as useful, educational and corresponding to expectations. However, correspondence between the subject matter and one’s own work was one of the conditions for repeated participation.

“You get some extra challenges so it is not just everyday work.”

“You got into the group you were probably most interested in.”

3.3. Factors Supporting Success

Co-operation between special and primary health care, temporality, producing an operations model for guidance with the help of teamwork, learning and different types of actors are central in development work. Development work was supported by commitment on the part of both the employer and the employee. Development work was part of everyday work but required commitment and motivation. One nurse put it like this: “It’s relevant that we have people who are actually interested in the subject matter.”

A highly committed employee was considered a benefit for the whole organization. Employer’s commitment was considered mainly formal when it did not include investment in development work resources. Time as well as courage and skills to utilize work hours were considered the most important resource for development work. A wide selection of participants broadened the perspective for all. Closeness of the team and voluntary participation as well as the ability to adapt to new situation, experience of project work and good basic knowledge of the issue promoted the success of development work. In addition, teams needed a team leader who had things under control.

Guidance and contracts on time schedules, meeting frequency, goals and concretization of the goals as well as feedback and guidance concerning the progress of work supported the success of development work. From the perspective of patient care, consistent subject matter and freedom to develop it were important for the process. Participants’ appreciation of expertise was also essential.

“Our expertise is the basis for the development of practical work…”

There was also a need for continued of teamwork after the development work is finished. During the development work, common guidance situations for the team leaders or use of an online discussion channel and videoconferencing might promote the success of the project. Work community’s awareness of the development work promoted its success. The working method of the teams had some positive sides to it as well. It enabled the application of good development ideas from different places in real time.

3.4. Challenges of Development Work

Challenges of development work were related to teamwork, development results and resources. Many types of insecurities were related to development work. A multiactor and multidisciplinary approach was considered challenging as well as functional. Because the group consisted of people unfamiliar to each other, it took time to achieve mutual understanding. However, one nurse described it this as follows: “…it was good we didn’t know each other because this way we didn’t have any preconceptions.”

It is important that during the initiation of development work superiors and employees attend the information meeting together and that sufficient amount of time is preserved for setting the teamwork in motion. Involvement in development work offers an opportunity to learn, and as many people as possible should take part in it during their careers. Teamwork training would be useful because knowledge and experience speed up the initiation of the process.

There were doubts about achieving real results and whether or not the results would be utilized in practical work. The results of development work were presented in electrical form as well to ease the dissemination of information. The purpose was to use the patient education operations models in a way that actually benefits the patients. “Now people can contact, for example, the cardiac nurse directly in case they have some problems or questions.”

The participants were unsure about the impacts of development work on their own learning and wondered if teamwork could offer them a sufficient amount of information and skills for patient education. More training related to guidance and treating illnesses would be needed. Utilization of existing and newly developed structures (e.g. nurse networks), commitment of employers and care work managers to development work, resources and rewards were considered important.

4. DISCUSSION

The study shows that attachment to development work offered the staff a positive challenge to evolve and an opportunity to develop individual skills, the whole care process and collective learning in a network environment. The experience can be considered positive because individual desire to grow, referring to the will to face challenges and evolve in the job, affects the readiness to commit to change and take part in the execution [6,8, 19].

According to Fusilero et al. [13] development work requires motivation, project work skills and individual know-how. Superior’s trust in the abilities of an employee operated as an incentive in this study as well. From the perspective of the work community, delegating challenging assignments only to the most capable is risky and disregards the employees that really need to develop their skills. Occupational development was considered to benefit the whole organization and involvement of as many people as possible in this type of work was seen as a desirable goal because success in development work is a strengthening and rewarding experience [5,14]. Earlier studies have also indicated that maintenance and development of know-how is necessary for staff and patients alike in the context of patient education [2,3,7,18,21].

According to Henderson and Winch [18], the results of development work, in this case the practices developed to support the improvement of the quality of patient education, may remain disconnected if they are not fully supported by management and superiors. Giving feedback, acknowledgement and recognition together with positive attention and joint pondering are important for maintaining a high level of motivation. Development work should not be the responsibility of employees alone: supporters are needed, people who guide the group toward the goal through rocky patches. In this study the employees felt that feedback was random. Feedback and acknowledgement of good performance gives the work meaning and provides a break from everyday routines [11,16].

Network co-operation in teams and exchange of information and experiences, learning and production of new information were perceived as meaningful [10,12, 17]. Commitment on the part of both the employee and the employer affected the success of development work [9]. More extensive discussion on development work in the workplace and staff members’ and superiors’ support to participants in development work would have a positive impact on spreading the results of development work as well.

Objectives that were related to basic work supported the successfulness of the development work. Improvement of patient education was considered a meaningful and useful objective. However, it would be important to have joint discussions on the goals and available resources before the initiation of development work. When development is closely attached to the operation of the organization, operational culture and the use of staff expertise, the preconditions for operation are good [4,15, 20].

The interviewees and researchers had met previously during the development work, and familiarity had helped in creating a confidential co-operation relationship. There is a risk of a conscious or unconscious desire to please having an effect on the statements of the interviewees involved in these types of interviews [23]. Inductive content analysis was used in the research process. The researchers attempted to indicate the connections between the result, the interpretation and the material. The subjectivity of qualitative research limits the transferability of the results to other circumstances. Even the sample size was twenty four; it represented all patient groups and professional groups as well as special and primary care units. In addition, saturation was received. However, the results of this research can only be generalized in the context of patient education development work. The interpretations may be applied in similar contexts or with similar research subjects.

5. CONCLUSION

In conclusion, participation in development calls for commitment and motivation. It is important to take as much interest as possible in the purpose and objectives of development work and the recruitment of participants so that the initiation of development work is smooth and unproblematic. Development work should be part of basic work. However, it is important that development is considered an issue that is important for the whole work community and that participant receive support from colleagues and superiors. Participation in development work offers occupational learning opportunities. Evaluation and development of own work strengthens staff members’ occupational know-how. The results of this research may to some extent be utilized in the planning and execution of development work in the field of health care.

6. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We wish to extend our thanks to the nursing staff participating of this study.

![]()

![]()

REFERENCES

- Kanste, O., Lipponen, K., Kääriäinen, M. and Kyngäs, H. (2010) Effects of network development on attitudes towards work and well-being at work among health care staff in northern Finland. International Journal of Circumpolar Health, 69, 394-403. doi:10.3402/ijch.v69i4.17675

- Johansson, K., Salanterä, S. and Katajisto, J. (2007) Empowering orthopaedic patients through preadmission education: Results from a clinical study. Patient Education and Counseling, 66, 84-91. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2006.10.011

- Efraimsson, E., Hillervik, C. and Ehrenberg, A. (2008) Effects of COPD self-care management education at a nurse-led primary health care clinic. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 22, 178-185. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6712.2007.00510.x

- Ahgren, B. and Axelsson, R. (2007) Determinants of integrated health care development: Chains of care in Sweden. International Journal of Health Planning and Management, 22, 145-157. doi:10.1002/hpm.870

- Kerosuo, H. (2006) Boundaries in action. An activitytheoretical study of development, learning and change in health care for patients with multiple and chronic illnesses. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Helsinki, Helsinki.

- Arranz, P., Ulla, S., Ramos, J., del Rincon, C. and Lopez-Fando, T. (2005) Evaluation of a counseling training program for nursing staff. Patient Education and Counseling, 56, 233-239. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2004.02.017

- Kääriäinen, M. (2007) The quality of counselling: The development of a hypothetical model. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Oulu, Oulu.

- Smith, T., Ingersoll, G., Robinson, R., Hercules, H. and Carey J. (2008) Recruiting, retaining, and advancing careers for employees from underrepresented groups. The Journal of Nursing Administration, 38, 184-193. doi:10.1097/01.NNA.0000312756.68794.f8

- Kouri, P., Karjalainen-Jurvelin, R. and Kinnunen J. (2005) Commitment of project participants to developing health care services based on the Internet technology. International Journal of Health Informatics, 74, 1000-1011.

- Hallin, K. and Danielson E. (2008) Registered nurses perceptions of their work and professional development. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 61, 62-70.

- Johnson, A., Hong, H., Groth, M. and Parker, S.K. (2010). Learning and development: Promoting nurses’ performance and work attitudes. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 67, 609-620. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2010.05487.x

- Eraut, M. (2004) Informal learning in the workplace. Studies in Continuing Education, 26, 247-273. doi:10.1080/158037042000225245

- Fusilero, J., Lini, L., Prohaska, P., Szweda, C., Carney, K. and Mion, L. (2008) The career advancement for registered nurse excellence program. Journal of Nursing Administration, 38, 526-531. doi:10.1097/NNA.0b013e31818ebf06

- Innstrand, S.T., Espnes, G.A. and Mykletun, R. (2004) Job stress, burnout and job satisfaction: An intervention study for staff working with people with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 17, 119-126. doi:10.1111/j.1360-2322.2004.00189.x

- Häggström, E., Skovdahl, K., Flächman, B., Kihlgren, A.L. and Kihlgren, M. (2005) Work satisfaction and dissatisfaction—Caregivers’ experiences after two-year intervention in a newly opened nursing home. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 14, 9-19. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2702.2004.00977.x

- Kalisch, B.J., Curley, M. and Stefanov, S. (2007) An intervention to enhance nursing staff teamwork and engagement. The Journal of Nursing Administration, 37, 77- 84. doi:10.1097/00005110-200702000-00010

- Amos, M.A., Hu, J. and Herrick, C.A. (2005) The impact of team building on communication and job satisfaction of nursing staff. Journal for Nurses in Staff Development, 21, 10-16. doi:10.1097/00124645-200501000-00003

- Henderson, A. and Winch, S. (2008) Staff development in the Australian context: Engaging with clinical contexts for successful knowledge transfer and utilisation. Nurse Education in Practice, 8, 165-169. doi:10.1016/j.nepr.2007.04.009

- Gustafsson, C. and Fagerberg, I. (2004) Reflection, the way to professional development? Journal of Clinical Nursing, 13, 271-280. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2702.2003.00880.x

- Hasson, H. and Arnetz, J. (2008) The impact of an educational intervention for elderly care nurses on care recipients’ and family relatives’ ratings of quality of care: A prospective, controlled intervention study. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 45, 166-179. doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2006.09.001

- Laird-Fick, H.S., Solomon, D., Jodoin, C., Dwamena, F., Alexander, K. and Rawsthorne, L. (2011) Training residents and nurses to work as a patient-centered care team on a medical ward. Patient Education and Counseling, 84, 90-97. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2010.05.018

- Elo, S. and Kyngäs, H. (2008) The qualitative content analysis process. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 62, 107- 115. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x

- Polit, D. and Beck, C. (2011) Nursing research: Generating and assessing evidence for nursing practice. 9th Edition, Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia.

NOTES

*Conflict of Interest Statement: the authors have no conflicts of interest concerning this study.

#Corresponding author.