American Journal of Computational Mathematics

Vol.05 No.03(2015), Article ID:59553,41 pages

10.4236/ajcm.2015.53032

Nonlinear Waves in Solid Continua with Finite Deformation

K. S. Surana1, J. Knight1, J. N. Reddy2

1Department of Mechanical Engineering, University of Kansas, Lawrence, KS, USA

2Department of Mechanical Engineering, Texas A & M University, College Station, TX, USA

Email: kssurana@ku.edu, jknight@ku.edu, jnreddy@tamu.edu

Copyright © 2015 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received 28 July 2015; accepted 7 September 2015; published 11 September 2015

ABSTRACT

This work considers initiation of nonlinear waves, their propagation, reflection, and their interactions in thermoelastic solids and thermoviscoelastic solids with and without memory. The conservation and balance laws constituting the mathematical models as well as the constitutive theories are derived for finite deformation and finite strain using second Piola-Kirchoff stress tensor and Green’s strain tensor and their material derivatives [1] . Fourier heat conduction law with constant conductivity is used as the constitutive theory for heat vector. Numerical studies are performed using space-time variationally consistent finite element formulations derived using space-time residual functionals and the non-linear equations resulting from the first variation of the residual functional are solved using Newton’s Linear Method with line search. Space-time local approximations are considered in higher order scalar product spaces that permit desired order of global differentiability in space and time. Computed results for non-linear wave propagation, reflection, and interaction are compared with linear wave propagation to demonstrate significant differences between the two, the importance of the nonlinear wave propagation over linear wave propagation as well as to illustrate the meritorious features of the mathematical models and the space-time variationally consistent space-time finite element process with time marching in obtaining the numerical solutions of the evolutions.

Keywords:

Linear and Nonlinear Waves, Second Piola-Kirchoff Stress, Green's Strain, Constitutive Theories, Dissipation, Memory, Rheology, Finite Strain

1. Literature Review, Outline, and Significance

The subject of nonlinear wave propagation in which nonlinearity primarily arises due to consideration of finite deformation and finite strain is an area of significant interest due to the introduction of polymeric solids and their abundant use in industrial applications. Polymers can undergo finite deformation, finite strain, have a dissipation mechanism, and exhibit rheological behavior. Thus, the deformation physics in such materials is quite complex. Development of mathematical models for finite deformation and finite strain for solid continua in Lagrangian description using conservation and balance laws resulting in initial value problems (IVP) and time accurate numerical simulations of the evolution described by the IVPs is the main objective of this research.

A review of the published works related to the research presented here is given in the following. In the published works cited and discussed here we address four basic questions: 1) what is the source of nonlinearity, 2) type of material considered (elastic, viscoelastic, etc.), 3) constitutive theories, 4) methodology or approach used to obtain numerical solution of the resulting mathematical model. In reference [2] conservation and balance laws are considered and some aspects of the constitutive theories are also discussed with the main objective of obtaining simplified mathematical models with various assumptions that would permit theoretical or semianalytical solutions. Many specialized forms of the 1D and 2D wave equations and their possible solutions are discussed. Reference [3] considers solids under high-pressure shock compression. This book presents many aspects of mechanics, physics, and chemistry in such deformation. Plasticity or irreversible deformation processes are a central point of focus in this reference. The material in the book is largely devoted to experiments, design of experiments, and analysis of experimental data. Experimentally focused work on “nonlinear phenomena in the propagation of elastic waves in solids” is also presented in reference [4] . The authors consider Green’s strain and many applications to different and unique materials. Precise mathematical models used, the constitutive theories considered and their derivations are not given. In reference [5] , the authors consider a one degree of freedom oscillator subjected to an external force and a restoring viscoelastic force with memory based on a phenomenological approach. Such models are not valid in the thermodynamic sense and their extension to R2 and R3 is not possible [1] . Finite amplitude waves in isotropic elastic plates are considered by Lima and Hamilton [6] . A perturbation technique with semianalytical solution is used to obtain the solutions of the governing equation of equilibrium in Lagrangian description. Periodic harmonic solutions are presented. In reference [7] , thermoelastic small-amplitude wave propagation in nonlinear elastic media is considered. Helmholtz free energy density is expressed as a nonlinear function of the principal stretches and is used to derive the constitutive equation for stress. For thermoelastic material based on reference [1] , this approach of deriving constitutive theory is unfounded. This approach is applied to layered structures. Lima and Hamilton [8] presented a study of finite amplitude waves in isotropic elastic waveguides with arbitrary cross-sectional area using perturbation and modal analysis techniques to obtain the solutions of nonlinear equations of motion for harmonic motion. The second Piola-Kirchoff stress tensor is expressed as a quadratic function of the Green’s strain tensor using a special form given in references [9] [10] . A study of nonlinear deformation waves in solids and dispersion due to microstructures using Mindlin type model is considered in reference [11] . Finite volume method is used to study propagation and interaction of one-dimensional waves. Nonlinear transient thermal stresses and elastic wave propagation studies in thick temperature-gradient dependent FGM cylinder using a second-order point-collocation method are presented in reference [12] . In reference [13] , numerical simulations of linear and nonlinear waves in hypoelastic solids are presented using conservation element and solution element method (CESE). These investigations are hypothetical as the constitutive theories for hypoelastic solids are hypothetical since these constitutive theories cannot describe the constitution of solids. Numerical simulations of nonlinear elastic wave propagation in piecewise homogeneous media are considered in reference [14] . Wave reflection, transmission, and interaction of waves are not clearly demonstrated primarily due to complexity of the properties of the domain. Vibrations and wave propagation in thick FGM cylinders with temperature dependent material properties are investigated in reference [15] . A nodal discontinuous Galerkin finite element method is considered for nonlinear elastic wave propagation in reference [16] . Nonlinear transient stress wave propagation in thick FGM cylinder using a unified generalized thermoelasticity theory is considered in reference [17] . Nonlinear constitutive model for axisymmetric bending of annular graphene-like nanoplates with gradient elasticity enhancement effects is considered in reference [18] . In reference [19] , nonlinear semianalytical finite-element algorithm for the analysis of internal resonance conditions in complex wave guides is considered. Linear stress waves in elastic medium for infinitesimal deformation linear elasticity have been studied by Surana et al. [20] .

From the brief literature review presented here we note the following. 1) The mathematical models resulting from conservation and balance laws are not explicitly defined and stated in most cases. 2) The constitutive theories for thermoelastic and thermoviscoelastic materials with and without memory and the basis for their derivations are mostly absent. In many instances phenomenological approach is used. 3) A mix of various space-time decoupled methods based on finite volume, finite element approaches for discretization in space followed by some time integration scheme is used to obtain evolutions described by the IVPs. In many instances semi-ana- lytical approaches are considered for highly simplified mathematical models that lack the desired physics. 4) In the model problems considered and the numerical studies presented for them, the complexity of the physics of the model problem rarely permits the assessment of the importance of nonlinearity when compared to the corresponding solutions from the linear models. 5) The issue of time accuracy of numerical solutions is never addressed in any of the references. This is of utmost significance as only with the correct time evolution can we assess the importance and significance of the nonlinear wave propagation.

The outline of the work presented in the paper is given in the following. General considerations and scope of study are contained in Section 2. The mathematical models in R3 (3D) are presented in Section 3. The mathematical models in R1 (1D) are given in Section 4. The dimensionless forms of the mathematical models in R1 are presented in Section 4.4. The computational framework, the space-time finite element formulations based on space-time residual functional and the time marching procedure for computing evolutions are presented in Section 5. Descriptions of model problems, schematics, loadings, boundary conditions and the material coefficients are given in Sections 6, 6.1, and 6.2. Computations of evolutions, convergence of the solutions, converged numerical results for the three types of solid continua considered here are presented in Section 6.3. Summary of the work and the conclusions drawn from the work presented in this paper are given in Section 7.

There are many important and meritorious aspects of the present work compared to the published works. Conservation and balance laws including constitutive theories are presented in R3 and R1 for finite deformation and finite strain in Lagrangian description for thermoelastic and thermoviscoelastic solids with and without memory using second Piola-Kirchoff stress tensor and Green’s strain tensor as conjugate pair. Dimensionless forms of the mathematical models in R1 are used for presenting linear as well as nonlinear wave initiation, propagation, reflection and subsequent propagation. Some of the significant aspects of the present work are: 1) demonstration of the fact that nonlinear waves result in shock formation and complex thermal field due to dissipation. 2) Wave amplitude decay and base elongation due to dissipation are clearly demonstrated for linear as well as nonlinear waves in case of solid continua with damping. 3) Rheological behavior due to memory is demonstrated for thermoviscoelastic solid continua with memory. 4) The finite element formulations used based on space-time couple approach are shown to be free of inherent numerical dispersion. 5) Computations of evolutions for large values of time are presented to illustrate various aspects of linear and nonlinear wave propagation. 6) It is clearly shown that extremely low values of space-time residuals obtained for all numerical computations confirm time accuracy (i.e. proximity of the computed solutions to the theoretical solutions) of the results presented in the paper.

2. Considerations in the Present Study and the Scope of Work

The work presented here considers nonlinear wave propagation, reflection and interaction in thermoelastic solid continua and thermoviscoelastic solid continua with and without memory. The mathematical models in Lagrangian description consist of conservation and balance laws and the appropriate constitutive theories for stress tensor and heat vector [1] . The primary source of nonlinearity is due to finite deformation and finite strain. The contravariant second Piola-Kirchoff stress tensor and Green’s strain are used as conjugate pairs in the derivations of the balance laws and the constitutive theories. The solid continua are assumed compressible thus permitting finite deformation and associated changes in density. For thermoelastic solid, rate constitutive theory of order zero is used in which the contravariant second Piola-Kirchoff stress is a linear function of the Green’s strain tensor. The work presented here only considers thermal affects due to rate of entropy production associated with rate of dissipation due to rate of mechanical work, thus for thermoelastic solids, the energy equation and entropy inequality resulting from the first and second law of thermodynamics are not required. In the case of thermoviscoelastic solids with and without memory, the second Piola-Kirchoff stress tensor is decomposed into equilibrium stress tensor and deviatoric stress tensor. The constitutive theory for the second Piola-Kirchoff equilibrium stress tensor is derived in terms of thermodynamic pressure. The constitutive theory for deviatoric second Piola-Kirchoff stress tensor for thermoviscoelastic solids without memory is considered as a first order rate theory [1] in which the deviatoric second Piola-Kirchoff stress tensor is a linear function of the Green’s strain tensor and its material derivative. In the case of thermoviscoelastic solids with memory, the constitutive theory for deviatoric second Piola-Kirchoff stress tensor is a first order rate theory in deviatoric second Piola- Kirchoff stress tensor as well as Green’s strain tensor.

The mathematical models are non-dimensionalized for use in the computational framework. Explicit forms of the mathematical models are presented in R1. These models are used to study one dimensional nonlinear wave propagation, reflection, and interaction in the three types of solid continua considered here. Linear forms of these mathematical models based on small-strain small-deformation assumptions are also considered in the numerical studies. The evolutions of the nonlinear and linear waves are compared to demonstrate the differences between the two. Ramp and pulse stress loadings and pulse velocity loading are considered in the numerical studies.

The dimensionless form of the mathematical models in R1 are utilized to construct the space-time coupled finite element processes for an increment of time (giving a space-time strip) based on space-time residual func- tionals that are space-time variationally consistent, hence the computations during the entire evolution remain unconditionally stable. Evolutions are computed by time marching using the space-time strip. The space-time local approximations for the dependent variables over a space-time element are considered in higher order scalar product spaces that permit higher order global differentiability of the space-time approximations over a discretization of the strip as well as at the inter-strip boundaries. The minimally conforming spaces ensure the space- time integrals over discretization of a space-time strip are in the Riemann sense. This feature enables computations of time accurate evolutions.

3. Mathematical Models in R3

In this section we present mathematical models for thermoelastic and thermoviscoelastic solids with and without memory consisting of conservation and balance laws and the constitutive theories. The mathematical models are first presented in R3. These are then followed by explicit forms of the mathematical models in R1 for 1-D wave propagation including their dimensionless forms. Finite deformation and finite strain are considered in the mathematical models. Contravariant second Piola-Kirchoff stress and Green’s strain tensor are used as conjugate pairs [1] . Solid continua are considered compressible. In the mathematical models, the energy equation is only considered if the rate of mechanical work results in entropy production. The mathematical models are considered in Lagrangian description.

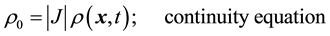

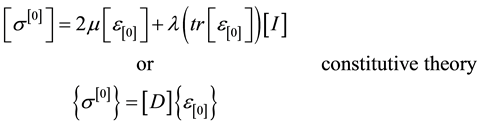

3.1. Thermoelastic Solid Continua in R3

In such solid continua the deformation process is reversible; hence rate of mechanical work does not result in rate of entropy production. Thus, the specific internal energy in the absence of strain energy is not affected by the rate of work. As a consequence, mechanical deformation and thermal effects remain uncoupled; hence the thermal behavior can be studied independent of the mechanical deformation. Since in the present work we only consider thermal effects due to rate of entropy production resulting from the rate of work, for thermoelastic solids the mathematical model only consists of conservation of mass, balance of linear momenta, and balance of angular momenta. The energy equation in this case is a linear (or nonlinear) diffusion equation and entropy inequality contains no dissipation terms but forms the basis for deriving constitutive theory for the heat vector appearing in the energy equation. The constitutive theory for the contravariant second Piola-Kirchoff stress

is based on

is based on

and Green’s strain tensor

and Green’s strain tensor

as conjugagte pair and is derived using strain energy

as conjugagte pair and is derived using strain energy

density function or theory of generators and invariants (see reference [1] for details). Thus for compressible thermoelastic solids, the mathematical model consists of continuity equation (conservation of mass), momentum equations (balance of linear momenta), balance of angular momenta, and the constitutive theory for the stress tensor. In the absence of body forces, we can have the following in Lagrangian description [1] . In the

constitutive equation for

we assume

we assume

as a linear function of

as a linear function of .

.

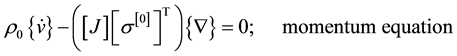

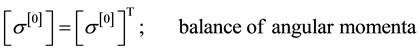

(3.1)

(3.1)

(3.2)

(3.2)

(3.3)

(3.3)

(3.4)

(3.4)

In which

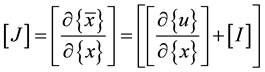

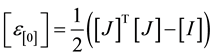

(3.5)

(3.5)

(3.6)

(3.6)

(3.7)

(3.7)

(3.8)

(3.8)

(3.9)

(3.9)

The

are coordinates of a material point

are coordinates of a material point

in which

hence

thermoelastic compressible solid continua,

final form of the mathematical model for thermoelastic solids in R3 in which (3.10) only needs to be used to determine

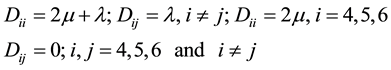

3.2. Thermoviscoelastic Solid Continua without Memory in R3

In such solid continua the deformation process is not reversible due to rate of mechanical work resulting in entropy production (dissipation) which affects the specific internal energy. Hence, in such solid continua, the material exhibits elasticity as well as dissipation mechanism but has no memory (or rheology). In such solid continua, the mechanical deformation and thermal effects are coupled implying that the energy equation resulting from the first law of thermodynamics is an integral part of the complete mathematical model. Entropy

inequality resulting from the second law of thermodynamics along with decomposition of

riving constitutive theory for heat vector and

[1] . The complete mathematical model for thermoviscoelastic solid continua without memory consists of conservation of mass, balance of linear momenta, balance of angular momenta, which are the same as in the case of thermoelastic solids (Equations (3.1)-(3.3)). Additionally, the energy equation and constitutive theories for

derivative of

theory for

and

Here

3.3. Thermoviscoelastic Solids with Memory in R3

In such solid continua the deformation process is also not reversible. In these solids the rate of mechanical work also results in rate of entropy production (dissipation). Additionally, such solids exhibit rheological behavior, i.e. memory. Due to rate of entropy production, the thermal and mechanical effects are coupled; hence the energy equation is an integral part of the complete mathematical model. Entropy inequality resulting from the second

law of thermodynamics along with the stress decomposition

ogy. Constitutive theory used for

following (in the absence of body forces).

where coefficients of

in the same manner as coefficients of

We consider compressive thermodynamic pressure to be positive, hence the negative sign in the constitutive theory for

tion. The constitutive theory for

solid continua without memory) in the following form if we neglect

divide throughout by

in which

Equation (3.26) is the final form used in the present work to obtain its equivalent form in R1.

Remarks:

Even though the model problems considered in the present work are wave propagation studies in R1, the mathematical models in R3 are necessary to demonstrate the presence of all relevant terms, many of which drop out in R1 as in R1 there is no concept of the other two dimensions.

4. Mathematical Models in R1

In this section explicit forms of the mathematical models for 1D wave propagation in R1 for thermoelastic and thermoviscoelastic solid continua with and without memory are presented. These models are derived using the mathematical models presented in Section 3 for the three dimensional case, i.e. in R3, hence they hold for finite deformation and finite strain. We assume directions 1 and

4.1. Thermoelastic Solid Matter (Compressible): R1

For 1D wave propagation in R1 the mathematical models of Section 3.1 in R3 reduce to

in which

Alternate form of the mathematical model using v

It is some times more convenient to introduce velocity

model. This form of the mathematical model is specially helpful in studies in which velocity needs to be speci-

fied as a boundary condition or initial condition. Thus, using velocity

This mathematical model contains dependent variables

4.2. Thermoviscoelastic Solids without Memory in R1

Using equations in Section 3.2, we can obtain the following in R1. We consider

in which

of known

Remarks

For solid matter the equation of state is rather involved [1] even though there is no particular problem in incorporating it in (4.3). Since the main objective of this research is the study of linear and nonlinear wave pro-

pagation, the constitutive theory for

tion is applied to linear and nonlinear wave propagation so that the comparisons of linear and nonlinear wave propagation studies remain meaningful. This is obviously an assumption that will undoubtedly influence the model behavior, the extent of which is believed to be not serious. There is further work in progress that incorporates actual equations of state for

Using (4.4),

model can likewise be expressed either in terms of

this mathematical model contains the same stress measure as in case of thermoelastic solids 4.1.

The factor of

constitutive theory. Here also

including continuity) in five dependent variables

has closure. Material coefficients

spectively. An alternate form of (4.5) can be derived by using

pared to (4.5)) but also contains additional equation

4.3. Thermoviscoelastic Solids with Memory in R1

Using the mathematical model of Section 3.3 (in R3) we can obtain the explicit form of the equations in the mathematical model in R1. In this case also we employ Equation (4.4). The final form of the equations for the

mathematical model in R1 is given in the following (in terms of

Here

This model has five equations and five dependent variables (same as for thermoviscoelastic solids without memory). Similar to Section 4.2, here also, we can derive an alternate form of (4.6) by using velocity

dependent variable. Here also

4.4. Dimensionless Form of the Mathematical Models in R1

We present the dimensionless forms of the mathematical models given in Sections 4.1-4.3 by choosing appropriate reference quantities. We consider the mathematical models derived in Sections 4.1-4.3 and introduce

hat

dimensions or units in terms of force

dimensionalizing. Additionally, we may have to choose other reference quantities too, for example,

temperature

speed of sound is a good choice for reference velocity

and

Using (4.7), the mathematical models in Sections 4.1-4.3 can be nondimensionalized.

4.4.1. Thermoelastic Solids: R1

The dimensionless forms are the same as in Section 4.1, Equations (4.1) and (4.2), with and without velocity as a dependent variable respectively, hence they are not repeated here for the sake of brevity.

4.4.2. Thermoviscoelastic Solids without Memory: R1

The mathematical model in Section 4.2 (Equations (4.5)) can be nondimensionalized using (4.7). The resulting dimensionless forms of the equations are

The dimensionless modulus of elasticity is given by

troduce velocity,

placed by

4.4.3. Thermoviscoelastic Solids with Memory: R1

The mathematical model in Section 4.3 (Equation (4.6)) can be nondimensionalized using (4.7). The resulting dimensionless form of the equations are

where Deborah number

5. Computational Framework for Numerical Simulation of Evolution

The mathematical models described in Sections 3 and 4 are a system of nonlinear partial differential equations (for finite strain measures) describing evolutions i.e. these are initial value problems (IVPs). Even in R1, the equations are complex enough not to permit theoretical or analytical solutions. In the present work, we consider a space-time coupled finite element formulation based on space-time residual functional for an increment of time with time marching for computing evolutions. The space-time local approximations are considered in higher order scalar product spaces that permit higher order global differentiability in space and time. Details of space-time coupled methods for IVPs, time marching, higher order global differentiability approximation spaces, space-time variationally consistent integral forms etc. can be found in references [21] -[30] . In the following we present a summary.

5.1. Space-Time Finite Element Formulation Based on Residual Functional and the Solution Procedure

For the sake of simplicity, we consider mathematical models in R1 describing one-dimensional wave propagation in thermoelastic and thermoviscoelastic media with and without memory. This choice is due to simplicity of physics so that the significant and subtle features of linear and non-linear wave propagation can be clearly demonstrated. Thus the mathematical models in Section 4 (R1) contain

or

Equations (5.1) or (5.2) are a system of

terms. In (5.1),

subdivision of the space-time domain

The nth space-time strip, with domain

in which

If we substitute

Figure 1. Space-time domain, space-time strips, and discretization for nth space-time strip. (a) Space-time domain; (b) Space-time strips

On the other hand, if we substitute

We consider the space-time finite element method based on residual functional (space-time least squares method). See references [21] -[30] for more details. Let

Since

Based on the calculus of variations [21] , an extremum of the functional

Thus,

In (5.11),

This is a unique extremum principle (see reference [21] for details). Since some of the equations in the mathematical model are nonlinear, some

(5.10) is a nonlinear function. Consider the local approximations

and

in which

dependent variable

the dependent variables

With (5.13) and (5.14),

Let

We expand

Then

An improved solution,

Use of

which when approximated using (5.12) gives a positive definite coefficient matrix due to the fact that

in which

5.2. Time Marching Procedure: Computations of Evolution

We initiate computations with the first space-time strip shown in Figure 2 with boundary conditions on two boundaries (for example) and initial conditions at time

continued till the desired time

6. Model Problems

We consider one-dimensional axial wave propagation in thermoelastic solid continua and thermoviscoelastic solid continua with and without memory. In all three mathematical models (Section 4.4) Green’s strain tensor is used as a measure of finite strain and the second Piola-Kirchoff stress tensor as energy conjugate stress measure. Figure 3(a) shows a schematic of the dimensionless rod of length one unit. The fixed end at

Figure 2. First two space-time strips with BCs and ICs.

Figure 3. Problem schematic, stress pulse, stress ramp, and velocity pulse loading. (a) Schematic; (b) Stress pulse loading: L1; (c) Stress ramp loading: L2; (d) Velocity pulse loading: L3.

origin of the x-frame. The dimensionless axial rod is of unit length. The right end of the rod (at

6.1. Loadings

We consider three different types of loads applied to the end of the rod at

Loading L1:

This loading consists of a stress pulse

The stress pulse

Loading L2:

This loading consists of stress

The ramp

Loading L3:

This loading (Figure 3(d)) consists of a velocity pulse,

The velocity

6.2. Material Coefficients, Reference Quantities and Dimensionless Parameters

We define the material coefficients for thermoelastic sold continua and the thermoviscoelastic solid continua with and without memory, choice of reference quantities, and the resulting dimensionless material coefficients and the dimensionless variables and the parameters. The basic material is hard rubber or polymer which we would treat as thermoelastic, thermoviscoelastic without memory as well as with memory.

Thermoelastic Solid Continua (TE)

If we choose

Thermoviscoelastic Solid without Memory (TVE)

reference speed of sound

reference time

characteristic kinetic energy.

If we choose

Thermoviscoelastic Solid with Memory (TVEM)

The material coefficients, reference quantities, and dimensionless quantities and parameters for TVE hold

here. Additionally for this solid continua we have Deborah number,

ues of

6.3. Computations of Evolutions: Numerical Results

In the following sections we report numerical studies for loading L1 and L2 for TE, TVE, and TVEM solid continua. Evolution in each case is computed using space-time strip with time marching until the desired value of time is reached. The choice of

space-time local approximation function is important. Since all three mathematical models (dimensionless forms given by (4.1), (4.8), and (4.9)) are a system of first order partial differential equations in space coordinate

first space-time strip with loading L2 and

degrees of freedom for TE, TVE solids and for TVEM. Plots of residual function I versus degrees of freedom for TE, TVE, and TVEM for both linear and nonlinear cases corresponding to infintesimal (linear) and finite strain formulations (nonlinear) are given in Figure 4. In the mathematical models,

case), the strain measure is Green’s strain and

continuity equation. From the graphs in Figure 4, we note that: 1) in all three cases (TE, TVE, and TVEM) the

residual I is of the order of

choices of h, p, and k, the evolution is expected to stay accurate as long as I of the order of

Figure 4. Convergence of residual functional I: I versus dof. (a) TE; (b) TVE; (c) TVEM.

6.3.1. Linear and Nonlinear Waves in TE Solid Continua

In this section, we present computed evolutions for TE solid continua for linear and nonlinear cases. In linear wave propagation with infintesimal deformation, there is no change in density and the stress

compressive

Loading L1

(a) Compressive

We consider a compressive stress pulse with

When

Figures 6(a)-(f) show plots of velocity v over

Figure 5. Evolution of

Figure 6. Evolution of

wave lags the linear case. Most dramatic is the reflection of the velocity wave shown in Figure 6(c) and its exploded view in Figure 6(d). Dramatically different behaviors for linear and nonlinear waves are clearly observed, yet upon further evolution, the wave shape is recovered (Figure 6(e) for

(b) Tensile

In this study, we choose a tensile stress pulse with

Loading L2

(a) Compressive

In this study, we consider loading L2 with

(b) Tensile

In this study, we consider tensile stress loading with

6.3.2. Linear and Nonlinear Waves in TVE Solid Continua

In this section, we consider linear and nonlinear waves in TVE solid continua. These solids have elasticity, mechanism of dissipation i.e. conversion of mechanical energy into entropy production which results in heat, hence influences specific internal energy. The dissipation mechanism is obviously present in linear (small strain) as well as nonlinear cases (Green’s strain). For linear case,

continua, Section 6.3.1)

constant wave speed during evolution. In the case of TVE solid continua, we can take more liberty with the magnitude of stress

Figure 7. Evolution of

Figure 8. Evolution of

Figure 9. Evolution of

Loading L1

(a) Compressive

Evolutions are computed for compressive pulse of

(b) Tensile

When

Loading L2: Tensile

In this case we consider tensile ramp loading with

6.3.3. Linear and Nonlinear Waves in TVEM

Loading L1: Compressive and Tensile

Figure 10. Evolution of

Figure 11. Evolution of temperature θ along the length of the rod: TVE, L1, Δt = 0.1, σ1 = −0.1. (a) t = 5Δt; (b) t = 9Δt; (c) Reflection, t = 11Δt; (d) Details of reflection, t = 11Δt; (e) t = 17Δt; (f) t = 23Δt.

Figure 12. Evolution of

Figure 13. Evolution of temperature θ along the length of the rod: TVE, L1, Δt = 0.1, σ1 = 0.1. (a) t = 5Δt; (b) t = 9Δt; (c) Reflection, t = 11Δt; (d) Details of reflection, t = 11Δt; (e) t = 17Δt; (f) t = 23Δt.

Figure 14. Evolution of

Figure 15. Evolution of temperature θ along the length of the rod: TVE, L2, Δt = 0.1, σ1 = 0.4. (a) t = 5Δt; (b) t = 9Δt; (c) Reflection, t = 11Δt; (d) Details of reflection, t = 11Δt; (e) t = 17Δt; (f) t = 23Δt.

TVEM are solid continua with dissipation and memory (rheology). If the damping coefficient is same in TVE and TVEM, then the dissipation remains the same in both. Thus for the same damping coefficient in TVE and TVEM, the only difference in the behavior of stress wave in TVEM compared to TVE solid is due to rheology i.e. stress relaxation. Thus, in this study the most meaningful illustration is the comparison of nonlinear stress waves for TVE and TVEM. We choose

Due to damping, the wave magnitudes progressively diminish along with base elongation as evolution proceeds. For TVEM, the peak values of pulse are consistently higher due to rheology, i.e. stress relaxation. In this case, the relaxation time (De) controls the relaxed state and hence additional time is required to achieve the same lower peak values as for TVE solid continua. For example, in Figure 16(a), Figure 16 (b), Figure 16 (e), and Figure 16(f), the peaks corresponding to TVEM (dashed line) will achieve the same lower values as the corresponding peaks for TVE solid continua (solid lines) if more time was allowed to elapse. Secondly, we note that the supports of the stress waves for TVEM are shorter than those of the corresponding TVE solid continua.

Similar results are presented in Figures 17(a)-(f) for

Loading L2: Tensile

For loading L2, we consider

6.3.4. Evolution for Large Values of Time: Tensile

In the studies presented here, we consider loading L2 for TVE and also for TVEM. We choose

Figure 20 shows plots of displacement

studies are obtained. The displacement values

TVE Solid Continua:

TVEM Solid Continua:

These values of displacements at

Figure 16. Comparison evolution of

Figure 17. Comparison evolution of

Figure 18. Evolution of

Figure 19. Evolution of temperature θ along the length of the rod: TVEM, L2, Δt = 0.1, σ1 = 0.4. (a) t = 5Δt; (b) t = 9Δt; (c) Reflection, t = 11Δt; (d) Details of reflection, t = 11Δt; (e) t = 17Δt; (f) t = 23Δt.

Figure 20. Displacement μ at x = 1:0: TVE, L2, Δt = 0.1, σ1 = 0.4.

Figure 21. Displacement μ at x = 1:0: TVEM, L2, Δt = 0.1, σ1 = 0.4.

Figure 20 and Figure 21. We observe that: 1) displacement

linear case as expected due to increase of stiffness caused by tensile stress field which results in lower values of displacement. This holds true in Figure 20 and Figure 21 as well during the evolution. 2) In the case of TVEM,

the displacement values for

that upon complete stress relaxation the TVEM behavior is the same as the behavior of TVE solid continua. However, the peak values in Figure 21 for linear as well as nonlinear cases are not the same as the corresponding values in Figure 20. Figure 22 shows plots of peak positive displacement of the free end

differences in the displacement values for TVE solid continua and TVEM solid continua for linear case

Remarks

Numerical studies were also conducted for loading L3 consisting of a velocity pulse. We note that if a velocity pulse of the same signature as generated by the loading L1 is applied at

Figure 22. Peak positive displacement of free end

7. Summary and Conclusions

In this paper, initiation, propagation, reflection, and the interaction of one-dimensional nonlinear waves in thermoelastic solid continua and thermoviscoelastic solid continua with and without memory have been presented. The mathematical models are first presented in R3 and then specialized for R1 for 1D wave propagation. The second Piola-Kirchoff stress and Green’s strain tensors are used as conjugate pairs in the conservation and balance laws. The constitutive theory for the second Piola-Kirchoff stress tensor is a linear function of Green’s strain tensor for TE. For TVE and TVEM, the constitutive theories are linear in strain tensor, its material derivative, and the material derivative of the second Piola-Kirchoff stress tensor. The constitutive theory used for heat vector is simple Fourier heat conduction law with constant thermal conductivity. The mathematical models for the nonlinear case consider the solid continua to be compressible. The mathematical models permit linear as well as nonlinear wave propagation studies. In the case of linear waves, the Green’s strain tensor becomes linearized small strain tensor and the second Piola-Kirchoff stress tensor is simply Cauchy stress tensor. For linear wave propagation the solid matter is incompressible.

In the case of thermoelastic solid continua, the rate of mechanical work does not result in rate of entropy production, hence the energy equation can be decoupled from the rest of the mathematical model. In this case, deformation i.e. wave propagation and thermal effect can be studied separately. For thermoviscoelastic solid continua with and without memory, the rate of mechanical work results in entropy production; hence in these solid continua energy equation is integral part of the mathematical models. The present work is based on some assumptions in order to simplify the mathematical model.

1) The equilibrium second Piola-Kirchoff stress is expressed as a function of thermodynamic pressure (equation of state) and

2) For compressible matter, the specific heat is a function of thermodynamic pressure (p) and temperature or density and temperature due to

3) Even though lack of precise account of compressibility in the energy equation may affect the overall results somewhat, the present forms used here are adequate enough to demonstrate the complex temperature distribution along the rod due to dissipation during wave propagation and reflection.

The space-time integral formulation based on space-time residual functional for a space-time strip with time marching is highly meritorious in (a) reducing the problem size, (b) ensuring accurate evolution for the current space-time strip before time marching is commenced. When the space-time residual functional is

From the numerical studies we observe the following.

1) In thermoelastic solid continua, linear or nonlinear waves maintain their amplitude and support for all space-time strips as well as for extended time evolution confirming that the computational process utilized here is elatively free of numerical dispersion.

2) The compressive nonlinear waves lag the linear waves due to increased density, hence reducing wave speed.

3) The tensile nonlinear waves lead the linear waves because of reduced density, hence increasing wave speed.

4) Both 2) and 3) hold for thermoelastic solid continua as well as thermoviscoelastic solid continua.

5) In both thermoviscoelastic solid continua with memory as well as the thermoviscoelastic solids without memory, the wave amplitude decays and the wave base elongates as evolution proceeds due to dissipation i.e. conversion of mechanical energy into entropy which results in temperature rise along the length of the rod. Complex temperature distribution due to dissipation is free of oscillations and is simulated without any difficulty together with the deformation field.

6) Progressively changing density due to compressibility or elongation results in progressively changing wave speed which finally results in piling up of waves forming a shock. This phenomenon exists in compressive as well as tensile nonlinear waves when the matter is compressible. Compared to linear waves, in the case of nonlinear compressive waves the shock formation occurs behind the linear wave, whereas in the case of tensile wave the shocks are formed ahead of the linear wave. Since in tension, large values of

7) In the case of TVEM, the results are similar to TVE solid continua except that in case of TVEM momentarily higher stress magnitudes are observed during evolutions because of rheology.

8) From the extended time evolutions shown in Figure 20 and Figure 21 for TVE and TVEM (for L2 loading) for 4000 time steps we make some remarks.

a) Transient response has dramatically higher displacements than the static response. A rod of length one unit is elongated as much as 0.75 units during evolution.

b) Evolutions are smooth and free of numerical dispersion and are time accurate. This is confirmed by I values

c) Linear and nonlinear responses differ significantly. Tension increases the effective stiffness value as compression reduces it.

d) Peak positive displacements for linear and nonlinear cases for TVE and TVEM shown in Figure 22 show the differences in linear and nonlinear responses quite clearly.

This work demonstrates the significance of nonlinearity due to Green’s strain and the need for incorporating it in wave propagation studies involving finite deformation. This is dramatically illustrated for tensile loading (L2) with

Acknowledgements

The computational infrastructure and the computational resources provided by the computational mechanics laboratory (CML) of the Department of Mechanical Engineering of the University of Kansas are gratefully acknowledged.

Cite this paper

K. S.Surana,J.Knight,J. N.Reddy, (2015) Nonlinear Waves in Solid Continua with Finite Deformation. American Journal of Computational Mathematics,05,345-386. doi: 10.4236/ajcm.2015.53032

References

- 1. Surana, K.S. (2014) Advanced Mechanics of Continua. CRC Press, Boca Raton.

- 2. Engelbrecht, J. (1983) Nonlinear Wave Processes of Deformation in Solids. Pitman Publishing, London.

- 3. Graham, R.A. (1993) Solids under High-Pressure Shock Compression. Springer-Verlag, New York.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4613-9278-1 - 4. Zarembo, L.K. and Krasil’nikov, V.A. (1970) Nonlinear Phenomena in the Propagation of Elastic Waves in Solids. Soviet Physics Uspekhi, 13, 778-797.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1070/PU1971v013n06ABEH004281 - 5. Fosdick, R., Ketema, Y. and Yu, J.H. (1997) A Non-linear Oscillator with History Dependent Force. International Journal of Non-Linear Mechanics, 33, 447-459.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1070/PU1971v013n06ABEH004281 - 6. Lima, W.J.N. de and Hamilton, M.F. (2003) Finite-Amplitude Waves in Isotropic Elastic Plates. Journal of Sound and Vibration, 265, 819-839.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0022-460X(02)01260-9 - 7. Gei, M., Bigoni, D. and Franceschini, G. (2004) Thermoelastic Small-Amplitude Wave Propagation in Nonlinear Elastic Multilayers. Mathematics and Mechanics of Solids, 9, 555-568.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1081286504038675 - 8. Lima, W.J.N. de and Hamilton, M.F. (2005) Finite Amplitude Waves in Isotropic Elastic Waveguides with Arbitrary Constant Cross-Sectional Area. Wave Motion, 41, 1-11.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.wavemoti.2004.05.004 - 9. Renton, J.D. (1987) Applied Elasticity: Matrix and Tensor Analysis of Elastic Continua. Ellis Horwood, Chichester.

- 10. Landau, L.D. and Lifshitz, E.M. (1986) Theory of Elasticity. Pergamon Press, New York.

- 11. Engelbrecht, J., Berezovski, A. and Salupere, A. (2007) Nonlinear Deformation Waves in Solds and Dispersion. Wave Motion, 44, 493-500.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.wavemoti.2007.02.006 - 12. Shariyat, M., Lavasani, S.M.H. and Khaghani, M. (2010) Nonlinear Transient Thermal Stress and Elastic Wave Propagation Analyses of Thick Temperature-Dependent FGM Cylinders, Using a Second-Order Point-Collocation Method. Applied Mathematical Modeling, 34, 898-918.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.apm.2009.07.007 - 13. Yu, S.T.J., Yang, L., Lowe, R. and Bechtel, S.E. (2010) Numerical Simulation of Linear and Nonlinear Waves in Hypoelastic Solids by the CESE Method. Wave Motion, 47, 168-182.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.wavemoti.2009.09.005 - 14. Berezovski, A., Berezovski, M. and Engelbrecht, J. (2006) Numerical Simulation of Nonlinear Elastic Wave Propagation in Piecewise Homogeneous Media. Materials Science and Engineering A, 418, 364-369.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.msea.2005.12.005 - 15. Shariyat, M., Khaghani, M. and Lavasani, S.M.H. (2010) Nonlinear Thermoelasticity, Vibration, and Stress Wave Propagation Analyses of Thick FGM Cylinders with Temperature-Dependent Material Properties. European Journal of Mechanics A/Solids, 29, 378-391.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.euromechsol.2009.10.007 - 16. Li, Y., Vandewoestyne, B. and Abeele, K.V.D. (2012) A Nodal Discontinuous Galerkin Finite Element Method for Nonlinear Elastic Wave Propagation. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 131, 3650-3663.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1121/1.3693654 - 17. Shariyat, M. (2012) Nonlinear Transient Stress and Wave Propagation Analyses of the FGM Thick Cylinders, Employing a Unified Generalized Thermoelasticity Theory. International Journal of Mechanical Sciences, 65, 24-37.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmecsci.2012.09.001 - 18. Yu, Y.M. and Lim, C.W. (2013) Nonlinear Constitutive Model for Axisymetric Bending of Annular Graphene-Like Nanoplate with Gradient Elasticity Enhancement Effects. Journal of Engineering Mechanics, 139, 1025-1035.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)EM.1943-7889.0000625 - 19. Nucera, C. and di Scalea, F.L. (2014) Nonlinear Semianalytical Finite-Element Algorithm for the Analysis of Internal Resonance Conditions in Complex Waveguides. Journal of Engineering Mechanics, 140, 502-522.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)EM.1943-7889.0000670 - 20. Surana, K.S., Maduri, R. and Reddy, J.N. (2006) One Dimensional Elastic Wave Propagation in Periodically Laminated Composites Using h; p; k Framework and STLS Finite Element Processes. Mechanics of Advanced Materials and Structures, 13, 161-196.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15376490500451809 - 21. Surana, K.S. and Reddy, J.N. (2015) Mathematics of Computations and the Finite Element Method for Initial Value Problems. Book Manuscript in Progress.

- 22. Surana, K.S., Ahmadi, A.R. and Reddy, J. (2002) The k-Version of Finite Element Method for Self-Adjoint Operators in BVP. International Journal of Computational Engineering Science, 3, 155-218.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1142/S1465876302000605 - 23. Surana, K.S., Ahmadi, A.R. and Reddy, J. (2003) The k-Version of Finite Element Method for Non-Self-Adjoint Operators in BVP. International Journal of Computational Engineering Science, 4, 737-812.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1142/S1465876303002179 - 24. Surana, K.S., Ahmadi, A.R. and Reddy J. (2004) The k-version of Finite Element Method for Nonlinear Operators in BVP. International Journal of Computational Engineering Science, 5, 133-207.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1142/S1465876304002307 - 25. Winterscheidt, D. and Surana, K.S. (1993) p-Version Least-Squares Finite Element Formulation for Convection-Diffusion Problems. International Journal for Numerical Methods in Engineering, 36, 111-133.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/nme.1620360107 - 26. Winterscheidt, D. and Surana, K.S. (1994) p-Version Least Squares Finite Element Formulation for Two-Dimensional, Incopressible Fluid Flow. International Journal for Numerical Methods in Fluids, 18, 43-69.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/fld.1650180104 - 27. Bell, B.C. and Surana, K.S. (1994) A Space-Time Coupled p-Version Least-Squares Finite Element Formulation for Unsteady Fluid Dynamics Problems. International Journal for Numerical Methods in Engineering, 37, 3545-3569.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/nme.1620372008 - 28. Bell, B.C. and Surana, K.S. (1996) A Space-Time Coupled p-Version Least Squares Finite Element Formulation for Unsteady Two-Dimensional Navier-Stokes Equations. International Journal for Numerical Methods in Engineering, 39, 2593-2618.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-0207(19960815)39:15<2593::AID-NME968>3.0.CO;2-2 - 29. Surana, K.S., Reddy, J.N. and Allu, S. (2007) The k-Version of Finite Element Method for Initial Value Problems: Mathematical and Computational Framework. International Journal of Computational Methods in Engineering Science and Mechanics, 8, 123-136.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15502280701252321 - 30. Surana, K.S., Allu, S., Reddy, J.N. and Tenpas, P.W. (2008) Least Squares Finite Element Processes in hpk Mathematical Framework for Non-Linear Conservation Law. International Journal of Numerical Methods in Fluids, 57, 1545-1568.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/fld.1695 - 31. Reddy, J.N. (2004) An Introduction to Nonlinear Finite Element Analysis. Oxford University Press, New York.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198525295.001.0001 - 32. Bathe, K.J. (1996) Finite Element Procedures. Prentice Hall, New Jersey.

- 33. Riks, E. (1979) An Incremental Approach to the Solution of Snapping and Buckling Problems. International Journal of Solids and Structures, 15, 529-551.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0020-7683(79)90081-7