Vol.2, No.2, 162-169 (2010) doi:10.4236/health.2010.22024 SciRes Copyright © 2010 Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/ Health Modified rives-stoppa repair for abdominal incisional hernias Peter Nau, Clancy J. Clark, Mason Fisher, Gregory Walker, Bradley J. Needleman, E. Christopher Ellison, Peter Musc ar ella Department of Surgery, The Ohio State University, Columbus, America; Pete.Muscarella@osumc.edu Received 26 October 2009, revised 23 December 2009; accepted 24 December 2009. ABSTRACT Incisional hernias are a prevalent problem in abdominal surgery and occur in 11% of patients who undergo laparotomy. Primary suture clo- sure of incisional hernias results in a 31%-58% chance of recurrence. The addition of a pros- thetic mesh implant decreases recurrence rates to 8%-10%. Popularized in Europe by Rives and Stoppa, the sublay technique has proven to be very effective, with low recurrence rates (0%-23%) and minimal complications. The pur- pose of the study was to evaluate the experi- ence of a single surgeon at a large tertiary care center performing a modified Rives-Stoppa re- p air for abdominal incisional hernias. To do this, the records of all patients undergoing a modi- fied Rives-Stoppa incisional hernia repair be- tween January 2000 and August 2003 were ret- rospectively reviewed. Outpatient clinic notes, discharge summaries, operative reports, and laboratory data were reviewed for patient demographics, surgical data and postoperative complications. Univariate analysis was per- formed in order to identify predictors for recur- rence. During the study period, 83 patients un- derwent a modified Rives-Stoppa incisional hernia repair. Nineteen patients were excluded due to incomplete medical records. No patients required postoperative exploration for an in- tra-abdominal catastrophe. Twenty-five percent (n=16) of patients had a complication as a result of the hernia repair. Only two patients (3.1%) developed recurrent incisional hernias. History of diabetes (p=0.007) and benign prostatic hy- perplasia (p=0.000) were the only significant predictors for recurrence. The results presented here confirm that the modified Rives-Stoppa retromuscular repair is an effective method for the repair of incisional hernias. The complica- tion and recurrence rates compare favorably to results for currently popular alternative tech- niques. Keywords: Incisional Hernia Repair; Mesh; Rives-Stoppa Repair; Abdominal Wall Defects 1. INTRODUCTION Incisional hernias are a common problem in abdominal surgery and occur in up to 11% of patients who undergo laparotomy [1]. Complications of incisional hernias in- clude infection, ulceration, incarceration of viscera, and small bowel obstruction [2-4]. Patients also experience discomfort and a cosmetically unpleasing bulge at the incision site. Successful repair of incisional hernias con- tinues to be challenging. Primary suture closure of inci- sional hernias results in recurrence rates of 31%-58% [5-10]. The addition of prosthetic mesh implants has been shown to decrease the incidence of recurrence to 8%-10% [11-14]. A tension-free prosthetic mesh repair of incisional hernias dates back the to 1940’s and 1950’s with the introduction of metal wire mesh and polypropylene mesh respectively [15-17 ]. With the development of new prosthetic materials, advances in minimally invasive techniques, and improvements in open surgical proce- dures, surgeons continue to debate the appropriate op- erative technique for the repair of incisional hernias, particularly regarding the anatomic placement and type of prosthetic mesh. Various operative techniques for in- cisional hernia repair use onlay, sublay (retromuscular or extrafascial), or underlay (intraperitoneal or subfascial) placement of mesh. Popularized in Europe by Rives and Stoppa, the sublay technique has proven to be very ef- fective, with low recurrence rates (0%-23%) and mini- mal complications [18-25]. Disadvantages include com- plexity, long operative times, and the possibility of chronic abdominal pain [26]. The experience of one surgeon at The Ohio State University Medical Center suggests that a modified HEALTH /  P. Nau et al. / Health 2 (2010) 162-169 SciRes Copyright © 2010 Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/ HEALTH / 163 Rives-Stoppa incisional hernia repair compares favora- bly to the standard Rives-Stoppa repair as well as to other techniques for addressing incisional hernias. The purpose of this study was to fully characterize the com- plications and recurrence rates of this surgical technique by conducting a retrospective review of patients who had undergone a modified Rives-Stoppa incisional hernia repair. 2. MATERIALS AND METHODS Between January 2000 and August 2003, 83 patients in the practice of one surgeon at a large urban academic hospital (The Ohio State University Medical Center) underwent a modified Rives-Stoppa incisional hernia repair. Of the 83 patients initially identified, 19 patients were excluded due to incomplete medical records. Out- patient clinic notes, discharge summaries, operative re- ports, and laboratory data of 64 patients were reviewed. There were 20 males and 44 females (mean age 50 years, range 27-85). The majority of incisional hernias were midline and supraumbilical, with several (n=3) flank hernias. Forty-five percent (n=29) of the incisional her- nias were recurrent (mean 2, range 1-7, S.D.± 1.6). At the time of repair, most incisional hernias were sympto- matic and evident on physical exam. Six percent (n=4) were incarcerated at the time of presentation and one patient had an inf ected abdominal wound (Table 1). The operative technique is a variation of the previ- ously described Rives-Stoppa technique [18,22,27]. All patients received intravenous prophylactic antibiotics (Cefazolin, 1 g) prior to incision. Patients were placed supine for midline hernias, or in lateral decubitus for flank hernias. The old incision scar and hernia sac were removed en bloc using an elliptical incision. Dissection of the hernia sac in all patients required entry into the peritoneum and division of adhesions to the sac, if iden- tified. The fascial plane between the rectus muscle and posterior rectus sheath was dissected as far lateral as possible, typically 5-10 cm, between eight and ten poly- butester (Novofil, United States Surgical/Syneture, Norwalk, CT) “U-stitch” anchoring sutures were placed only in the posterior rectus sheath, not penetrating the rectus muscle, anterior rectus sheath or skin. The fascial defect was closed by reapproximating the posterior rec- tus sheath with running polybutester suture reinforced with simple interrupted polybutester suture (Figure 1). Tension was minimal and the posterior rectus fascia was closed in all 64 patients. Below the arcuate line, the peritoneum was carefully reapproximated. Monofila- ment polypropylene mesh (Bard Mesh Flat Sheets, Davol Inc., Cranston, RI) was cut to size slightly larger (5 cm overlap) than the fascial defect and anchored us- ing the previously placed sutures (Figure 2). Cefazolin (1 g) powder was placed on the mesh prior to closure of Table 1. Hernia characteris tics. N (%) Recurrent 29 (45.3) Location Supraumbilical 42 (65.6) Umbilical 9 (14.1) Infraumbilical 8 (12.5) Paramedian 1 (1.6) Subcostal 1 (1.6) Flank 3 (4.7) Symptomatic 59 (92.2) Evident on Physical Exam61 (95.3) Incarcerated 4 (6.4) Infected 1 (1.6) Ulcerated 0 (0) the anterior rectus sheath (Figure 3). In the majority of the patients (n=46), one to two bulb suction drains were placed between the skin and the anterior rectus sheath. The skin was approx imated with interrupted, d ermal 2-0 polyglycolic acid sutures (Dexon II, Syneture, Norwalk, CT) and staples. Oral prohylactic antibiotics (Cefalexin, 500 mg PO TID) were started postoperatively and con- tinued until drain removal. Hospital discharge typically occurred on post-operative day 3 (mean 5, range 2-29, S.D.± 3.9). Follow-up information was available for 61 patients, with mean follow-up of 20 weeks (range 1-144 weeks, S.D.± 30.1) and mean number of follow-up visits of three (range 1-13, S.D. ± 2.9). All patients were exam- ined during follow-up by the surgeon who completed the operation. Three patients had no follow-up information available and their records indicated that another physi- cian is currently following them. Physician correspon- dence information was reviewed to determine any com- plications or recurrences in these three patients. One patient died of causes unrelated to the repair of the inci- sional hernia, and there is no evidence that any of these patients developed a recurrent incisional hernia. This study was approved by the medical center institutional review board. Statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS for Windows (Version 11.5.0, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). 3. RESULTS All 64 patients tolerated the procedure well with no in- traoperative complications. There were two (3.1%) pe- rioperative complications. No myocardial infarctions or cases of pneumonia were recorded. One patient suffered a pulmonary embolism and was treated with anticoagu- lant therapy. The second patient was readmitted for drainage of a rectus sheath hematoma found anterior to the prosthetic mesh. Three (4.7%) patients required pe- rioperative packed red blood cell transfusions. Blood loss was negligible, with a mean post-operative d ecrease n hemoglobin of 0.8 g/dl (S.D. ±1.3). i  P. Nau et al. / Health 2 (2010) 162-169 SciRes Copyright © 2010 http://www.scirp.org/journal/ 164 Figure 1. The posterior rectus sheath is dissected away from the overlying rectus abdominus muscle on both sides of the defect using electrocautery. The peritoneum is mobilized below the level of the arcuate line. Care must be taken to ligate and divide perforating blood vessels, as unidentified injury to these structures could result in the formation of rectus hematomas postoperatively. The posterior layer is approximated with running suture and reinforced in- termittently with additional suture in order to avoid excess tension and tearing during ma- nipulation. Figure 2. Polypropylene mesh is trimmed and placed into the space behind the rectus muscle. Previously placed anchoring sutures are passed through the mesh and used for fixation. Openly accessible at HEALTH /  P. Nau et al. / Health 2 (2010) 162-169 SciRes Copyright © 2010 Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/ HEALTH / 165 Figure 3. Bulb suction drains are placed into the subcutaneous space and brought out of the skin through separate stab incisions. The skin is approximated with dermal sutures and staples in order to maintain an adequate seal for drain. There were complications in twenty-five percent (n=16) of patients as a result of the hernia repair. The majority of the complications were minor with only seven patients requiring admission to the hospital for management (15.6%). Six patients (9.4%) had superfi- cial wound or deep mesh infections, defined as purulent drainage or positive wound cultures. None required re- moval of the prosthetic mesh and all were successfully managed with antibiotics and wound management. One patient developed erythema adjacent to the skin staples, four (6.3%) developed seromas, and three (4.7%) de- veloped wound hematomas. In no case was evidence of infection, including erythema or purulent drainage noted in those patients with sero mas. Wound cultures were not performed routinely on suspected seromas in the absence of clinical signs of infection. A hematoma was defined as a fluid collection with bloody drainage. Although no patients developed fistulas, four patients (6.3%) pre- sented post-operatively with partial small bowel obstruc- tions, all of who were successfully treated with nasogas- tric decompression. Fifteen patients (23.4%) are being managed for chronic abdominal pain (Table 2). In the subgroup of morbidly obese patients (n=27), there were two partial small bowel obstructions (7 .4%), one seroma (3.7%), one hematoma (3.7%), and two surgical site in- Table 2. Complications. N (%) Infection 6 (9.4) Seroma 4 (6.3) Hematoma 3 (4.7) pSBO* 4 (6.3) Staple Reaction 1 (1.6) Fistula 0 (0) Chronic Pain 15 (23.4) Recurrence 2 (3.1) *partial small bowel obstruction. fections (7.4%).Two patients (3.1%) developed recurrent incisional hernias. The first patient developed a small (1-2 cm) supraumbilical recurrent hernia 10 months (post-operative day 285) following the hernia repa ir. The patient subsequently developed a second small perium- bilical hernia. The second patient was originally treated for a recurrent midline incisional hernia and a primary flank hernia. Recurrence of the flank hernia developed six weeks post-operatively (post-operative day 42). The flank hernia has recurred twice and it is believed that inadequate repair can be attribu ted to insufficient overlap of mesh and fascia or incomplete coverage of the fascial defect. Both patients had medical histories significant for diabetes and a respiratory disorder. The study p opulation was a typical patient populatio n for recurrent complex  P. Nau et al. / Health 2 (2010) 162-169 SciRes Copyright © 2010 Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/ HEALTH / 166 Table 3. Potential prognostic factors for hernia recurrence. N (%) p Smoking 18 (28.1) COPD* 8 (12.5.) 0.103 Asthma 7 (10.9) 0.072 Diabetes (Type I or II) 14 (21.9) 0.007 Sleep Apnea 12 (18.8) 0.490 Morbid Obesity 27 (42.2) 0.220 Chronic Steroid Use 3 (4.7) 0.750 Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia 2 (3.1) 0.000 Cirrhosis 3 (4.7) 0.750 Malabsorptive Surgery† 30 (46.9) 0.177 *COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. †Malabsorptive sur- gery defined as roux-en-Y gastric bypass (25), cystojejunostomy (1), choledochojejunostomy (3), or vertical banded gastroplasty (1). incisional hernias, with numerous potential risk factors for recurrence (Table 3). Forty-two percent of patients (n=27) were considered to be morbidly obese (BMI > 40 kg/m2) and 46.9% of patients (n=30) had previously undergone a surgical procedure that could potentially result in malabsorption (Rouxen-Y gastric bypass, choledocho-jejunostomy, etc.). In the subgroup of mor- bidly obese patients, no recurrences were observed. With univariate analysis, a history of diabetes (p=0.007) or benign prostatic hyperplasia (p=0.000) were the only significant pr ognostic factors for recurrence. 4. DISCUSSION Surgical techniques for the repair of incisional hernias continue to evolve with advances in prosthetic materials and minimally invasive technology. Luijendijk et al. conducted a randomized, multicenter study suggesting that mesh repair is superior to suture repair [28]. The optimal technique for mesh placement has not been es- tablished and re mains controversial. Laparoscop ic repair appears to have numerous benefits, including low recur- rence rates, decreased hospital length of stay, decreased postoperative pain, an d earlier return to work and normal activities. Although a single randomized trial has been designed [29], the results are still pending and no ran- domized controlled trials are available to prove any benefit of laparoscopic techniques over open repair. A meta-analysis by Goodney et al. indicated that laparo- scopic ventral hernia repair may have lower complica- tion rates [30]. Initial concern for increased fistula for- mation and small bowel obstruction with the laparo- scopic underlay techniques have also been raised, but appear to be less of concern with recent studies and changes in mesh technology [11]. It has been our ex- perience that catastroph ic abdominal complications, such as small bowel perforation, can occur with the laparo- scopic repair. Although this does not appear to occur frequently, these types of complications can be disas- trous in that they may require multiple surgeries, mesh removal, long-term wound care, and skin grafting pro- cedures. The end result is usually an incisional hernia that is larger than the initial hernia. There are currently no reliable methods fo r selecting appropriate patien ts for laparoscopic incisional hernia repair. The data from our study suggests that the technique described here is rarely, if ever, associated with these types of complications. The separation of components technique, originally described by Ramirez et al. in 1990 has recently drawn interest for complex incisional hernia rep air. After mobi- lization of skin flaps, the external oblique muscle is re- leased just lateral to its rectus sheath insertion from the underlying internal oblique muscle. This enables the well vascularized rectus abdominis muscle complex to be advanced medially, allowing for coverage of the her- nia defect [31]. Up to a 20 cm defect at the waist, 12 cm in the upper abdomen, and 10 cm in the lower abdomen can be closed using additional relaxing incisions. Ad- vantages include utilization of a dynamic muscle group that remains innervated for closure of the defect, and potentially improved cosmetic results as excess skin is commonly excised prior to closure of the wound. Shestak et al. reported only one recurrence, two superfi- cial wound infections, and one seroma in 22 patients undergoing this procedure [32]. In contrast, another study demonstrated recurrent hernias in 32.0% of pa- tients and complications, including fascial dehiscence, hematoma, seroma, wound infection, skin necrosis, and respiratory insufficiency, in 39.5% of patients [33]. The modified Rives-Stoppa technique allows for cosmeti- cally pleasing results, in that redundant skin is removed en bloc with the underlying hernia sac. Skin necrosis is rare because large skins flaps are not created and careful attention is paid to preserving the perforating blood ves- sels that supply the remaining skin and subcutaneous tissues. The Rives-Stoppa technique preserves the func- tionality and integrity of the abdominal wall, factors considered to be crucial for effective repair of abdominal wall defects by proponents of the separation of compo- nents technique. Furthermore, the Rives-Stoppa tech- nique employs the use of mesh as reinforcement, and this is generally believed to decrease recurrence rates as described previously. The data reported here indicate that a modified Rives-Stoppa retromuscular repair results in favorable recurrence and complication rates when compared with the standard Rives-Stoppa repair as well as other tech- niques. The experience of a single surgeon’s practice at The Ohio State University is comparable to previously reported results (Table 4). Benefits of this technique include the ability to explore the entire fascial defect and to identify any potentially weak points in the fascia. Fenestrations in the peritoneum can be recognized, and if necessary, selection of a larger mesh implant to cover  P. Nau et al. / Health 2 (2010) 162-169 SciRes Copyright © 2010 Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/ HEALTH / 167 Table 4. Studies of the rives-stoppa open mesh repair Seroma, N(%) Infection, N(%) Recur- rence, N(%) Knight et al. 2002 [18] 1 (1.5) 2 (3.1) 0 (0) Bauer et al. 2002 [19] 7 (12.3) 2 (3.5) 0 (0) Toniato et al. 2002 [22] -- 6 (7.8) 2 (2.6) Luijendijk et al. 2000 [21] 4 (4.8) 3 (4) 17 (23) Balen et al. 1998 [26] 2 (4.4) 1 (2) 1 (2) McLanahan et al. 1997 [24] 1 (1) 13 (13) 3 (3.5) Sugerman et al. 1996 [23] 5 (5) 17 (17) 4 (4) Temudom et al. 1996 [28] 3 (6) 6 (12) 2 (4) Adloff et al. 1987 [30] -- 3 (2.3) 6 (4) these areas of potential weakness can be made. Place- ment of the mesh between the posterior rectus sheath and the rectus muscle takes advantage of the intra-abd- ominal pressure to secure the mesh, while minimizing the risk of adhesion and fistula formation. Unique to this series of patients was the surgeon’s ability to close the posterior rectus sheath with suture. Extensive dissection of the plane between the posterior rectus sheath and the rectus muscle likely decreases tension when closing this layer. Inability to close the posterior rectus sheath re- quires bridging the fascial defect and would likely in- crease the risk of recurrence. It should be noted that the majority of the complica- tions in this series were minor and easily managed on an outpatient basis. Despite pre- and post-operative pro- phylactic antibiotics, bulb suction drainage, and direct placement of cefazolin powder on the prosthetic mesh, the infection rate still approached 10%. This may be attributed to patient factors, natural reaction to a foreign material, and/or long-term placement of bulb suction drains. Colonization of drain sites increases with time and they are a potential portal of entry for bacterial in- fection [34]. Criteria for drain removal generally re- quired that the drain output be less than 30 ml per day in an attempt to minimize the incidence of seroma forma- tion. As a result, drains remained in place for a mean duration of three weeks (range 7-85 days, S.D. ±15.7). Removing drains earlier might help to decrease infection rates. It is also unclear whether continuing oral antibiot- ics while the drains are in imparts any benefit for the patient, but was performed in order to decrease the chance of infection. The direct application of antibiotics on the mesh at the time of surgery is clearly controver- sial, but has been described previously [35,36]. The ra- tionale is to improve the local concentration of antibiot- ics and this may have potential benefits, particularly for obese patients in whom systemic antibiotic therapy may not be as effective. Although post-operative complica- tions were not significant risk factors for hernia recur- rence (data not shown), other studies have recognized an increased risk of recurrence following infection [28,37]. The concern is generally that infected mesh must be re- moved to successfully treat th e infection and removal of the mesh results in hernia recurrence. In a study of pa- tients undergoing concurrent incisional hernia repair and elective colon resections, the authors concluded that prosthetic mesh may be employed for incisional hernia repairs in contaminated fields without increasin g the risk of complications [38]. In a study comparing different mesh materials, Leber et al. concluded that multifila- ment polyester mesh (Mersilene) has a significantly in- creased risk of infection as compared to double-filament polypropylene mesh (Prolene) [39]. Infection rates vary among studies, but this is understandable given varia- tions in antibiotic usage, drain management, and types of mesh employed. Considering the current body of evi- dence, the appropriate prevention and management of wound infection in patients undergoing mesh incisional hernia repair remains to be determined. Chronic pain was a concern of almost a quarter of study patients, but comparison of pre and post-operative pain was not available in this study. The concern of chronic pain has also been raised in previous studies [12, 20]. McLanahan et al. reported that 11% of patients had moderate to severe pain at 12 months after incisional hernia repair [20]. In a 1997 symposium on incisional hernia repair, Schumpelick argued that mesh can limit range of motion and result in a stiff abdomen [21]. De- creased abdominal wall compliance has been confirmed with three dimensional stereography [40]. Given the potentially negativ e long-term effects of prosthetic mesh repair, data characterizing the quality-of-life, chronic pain, and physical limitations of mesh implants should prove to be helpful. Although diabetes and benign prostatic hyperplasia were the only identified risk factors for recurrence in this study, previously identified risk factors for recurrence were common in the study population. Considering the size and non-randomized nature of this study, it is possi- ble that we did not have sufficient statistical power to display the significance of these known risk factors. Sugerman et al. have shown that severe obesity is a greater risk factor for hernia recurrence than chronic steroid use [41]. In the subgroup of morbidly obese pa- tients we expected to see increased rates of recurrence and infection, however, this was not the case. The ma- jority of the obese patients who underwent hernia repair were actively losing weight from recent gastric bypass surgery. It is possible that weight loss, the presence of redundant skin, and general changes in body habitus facilitated the repair and decreased the risk of recur- rence. The modified Rives-Stoppa retromuscular repair, as described here, appears to be an effective treatment for incisional hernias. These results compare favorably with other published reports for the Rives-Stoppa repair and other techniques. The recurrence rate of 3.2% is clearly  P. Nau et al. / Health 2 (2010) 162-169 SciRes Copyright © 2010 Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/ HEALTH / 168 acceptable in this series that includes numerous patients with multiple risk factors, and a considerable number of patients who have failed previous attempts at repair. We also believe that the absence of catastrophic abdominal events following repair is important to note. Wound in- fection, chronic pain, and persistent abdominal stiffness continue to be problematic, but manageable. Random- ized prospective trials are required to determine the op- timum technique for incisional hernia repair. REFERENCES [1] Mudge, M. and Hughes, L.E. (1985) Incisional hernia: a 10 year prospective study of incidence and attitudes. Br J Surg, 72, 70–71. [2] Petersen, S., Henke, G.., Freitag, M., Faulhaber, A. and Ludwig, K. (2001) Deep prosthesis infection in incisional hernia repair: predictive factors and clinical outcome. Eur J Surg, 167, 453–457. [3] Read, R.C., and Yoder, G. (1989) Recent trends in the management of incisional herniation. Arch Surg, 124, 485–488. [4] Rives, J., Lardennois, B., Pire, J.C. and Hibon, J. (1973) [Large incisional hernias. The importance of flail abdo- men and of subsequent respiratory disorders]. Chirurgie, 99, 547–563. [5] George, C.D. and Ellis, H. (1986) The results of inci- sional hernia repair: a twelve year review. Ann R Coll Surg Engl, 68, 185–187. [6] Langer, S. and Christiansen, J. (1985) Long-term results after incisional hernia repair. Acta Chir Scand, 151, 217–219. [7] Luijendijk, R.W., Lemmen, M.H., Hop, W.C. and Were- ldsma, J.C. (1997) Incisional hernia recurrence following "vest- over-pants" or vertical Mayo repair of primary her- nias of the midline. World J Surg, discussion 66, 21, 62–65. [8] Manninen, M.J., Lavonius, M. and Perhoniemi, V.J. (1991) Results of incisional hernia repair. A retrospec- tive study of 172 unselected hernioplasties. Eur J Surg, 157, 29–31. [9] Stevick, C.A., Long, J.B., Jamasbi, B. and Nash, M. (1988) Ventral hernia following abdominal aortic recon- struction, Am Surg, 54,287–289. [10] van der Linden, F.T. and van Vroonhoven, T.J. (1988) Long-term results after surgical correction of incisional hernia, Neth J Surg, 40, 127–129. [11] Cassar, K. and Munro, A. (2002) Surgical treatment of incisional hernia, Br J Surg, 89, 534–545. [12] Korenkov, M., Sauerland, S., Arndt, M., Bograd, L., Neugebauer, E.A. and Troidl, H. (2002) Randomized clinical trial of suture repair, polypropylene mesh or autodermal hernioplasty for incisional hernia, Br J Surg, 89, 50–56. [13] Liakakos, T., Karanikas, I., Panagiotidis, H. and Dendri- nos, S. (1994) Use of Marlex mesh in the repair of recur- rent incisional h ern i a. Br J Surg, 81, 248–249. [14] Molloy, R.G., Moran, K.T., Waldron, R.P., Brady, M.P. and Kirwan, W.O. (1991) Massive incisional hernia: ab- dominal wall replacement with Marlex mesh. Br J Surg, 78, 242–244. [15] Crosthwait, R.W. (1960) Ventral hernia: a rapid method of repair. Am J Surg. 99, 330–331. [16] Usher, F.C., Ochsner, J. and Tu ttle Jr., L.L. (1958) Use of marlex mesh i n the repair of incisional hernias. Am Surg, 24, 969–974. [17] Validire, J., Imbaud, P., Dutet, D. and Duron, J.J. (1986) Large abdominal incisional hernias: repair by fascial ap- proximation reinforced with a stainless steel mesh. Br J Surg, 73, 8–10. [18] Bauer, J.J., Harris, M.T., Gorfine, S.R. and Kreel, I. (2002) Rives-Stoppa procedure for repair of large inci- sional hernias: experience with 57 patients. Herni a , 6, 120–123. [19] Knight, R. and Fenoglio, M.E. (2002) The use of the Kugel mesh in ventral hernia repairs. Am J Surg, 183, 642–645. [20] McLanahan, D., King, L.T., Weems, C., Novotney, M. and Gibson, K. (1997) Retrorectus prosthetic mesh repair of midline abdominal hernia. Am J Surg, 173, 445–449. [21] Schumpelick, V., Junge, K., Rosch, R., Klinge, U. and Stumpf, M. (2002) [Retromuscular mesh repair for ven- tral incision hernia in Germany]. Chirurg, 73, 888–894. [22] Stoppa, R.E. (1989) The treatment of complicated groin and incisional hernias. World J Surg, 13, 545–554. [23] Temudom, T., Siadati, M. and Sarr, M.G. (1996) Repair of complex giant or recurrent ventral hernias by using tension-free intraparietal prosthetic mesh (Stoppa tech- nique): lessons learned from our initial experience (fifty patients). Surgery, discussion 743–734,120, 738-743; [24] Toniato, A., Pagetta, C., Bernante, P., Piotto, A. and Pe- lizzo, M.R. (2002) Incisional hernia treatment with pro- gressive pneumoperitoneum and retromuscular prosthetic hernioplasty. Langenbecks Arch Surg, 387, 246–248. [25] Yaghoobi Notash, A., Yaghoobi Notash, A., Jr., Seied Farshi, J., Ahmadi Amoli, H., Salimi, J. and Mamarabadi, M. (2006) Outcomes of the Rives-Stoppa technique in incisional hernia repair: ten years of experience. Hernia. [26] LeBlanc, K.A. and Whitaker, J.M. (2002) Management of chronic postoperative pain following incisional hernia repair with Composix mesh: a report of two cases. Her- nia, 6, 194–197. [27] Rives, J. (1987) Major incisional hernia. In J. P. Chevrel (Ed.), Surgery of the abdominal wall, New York: Springer-Verlag, 116–144. [28] Luijendijk, R.W., Hop, W.C., van den Tol, M.P., de Lange, D.C., Braaksma, M.M., JN, I.J., Boelhouwer, R. U., de Vries, B.C., Salu, M.K., Wereldsma, J.C., Bruijninckx, C.M. and Jeekel, J.A. (2000) Comparison of suture repair with mesh repair for incisional hernia. N Engl J Med, 343, 392–398. [29] Itani, K.M., Neumayer, L., Reda, D., Kim, L. and An- thony, T. (2004) Repair of ventral incisional hernia: the design of a randomized trial to compare open and laparoscopic surgical techniques. Am J Surg, 188, 22S–29S. [30] Goodney, P.P., Birkmeyer, C.M. and Birkmeyer, J.D. (2002) Short-term outcomes of laparoscopic and open ventral hernia repair: a meta-analysis. Arch Surg, 137, 1161–165.  P. Nau et al. / Health 2 (2010) 162-169 SciRes Copyright © 2010 http://www.scirp.org/journal/Openly accessible at HEALTH / 169 [31] Ramirez, O.M., Ruas, E. and Dellon, A.L. (1990) "Com- ponents separation" method for closure of abdomi- nal-wall defects: an anatomic and clinical study. Plast Reconstr urg, 86, 519–526. [32] Shestak, K.C., Edington, H.J. and Johnson, R.R. (2000) The separation of anatomic components technique for the reconstruction of massive midline abdominal wall de- fects: anatomy, surgical technique, applications, and limitations revisited. Plast Reconstr Surg, quiz 739, 105, 731–738. [33] de Vries Reilingh, T.S., van Goor, H., Rosman, C., Be- melmans, M.H., de Jong, D., van Nieuwenhoven, E.J., van Engeland, M.I. and Bleichrodt, R.P. (2003) "Com- ponents separation technique" for the repair of large ab- dominal wall hernias. J Am Coll Sur g , 196, 32–37. [34] Drinkwater, C.J. and Neil, M.J. (1995) Optimal timing of wound drain removal following total joint arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty, 10, 185–189. [35] Dirschl, D.R., and Wilson, F.C. (1991) Topical antibiotic irrigation in the prophylaxis of operative wound infec- tions in orthopedic surgery. Orthop Clin North Am, 22, 419–426. [36] O'Connor Jr, L.T. and Goldstein, M. (2002) Topical pe- rioperative antibiotic prophylaxis for minor clean ingui- nal surgery. J Am Coll Surg, 194, 407–410. [37] Bauer, J.J., Harris, M.T., Kreel, I. and Gelernt, I.M. (1999) Twelve-year experience with expanded polytetra- fluoroethylene in the repair of abdominal wall defects. Mt Sinai J Med, 66, 20–25. [38] Birolini, C., Utiyama, E.M., Rodrigues Jr., A.J. and Bi- rolini, D. (2000) Elective colonic operation and pros- thetic repair of incisional hernia: does contamination contraindicate abdominal wall prosthesis use? J Am Coll Surg, 191, 366–372. [39] Leber, P.D. and Davis, C.S. (1998) Threats to the validity of clinical trials employing enrichment strategies for sample selection. Control Clin Trials, 19, 178–187. [40] Welty, G., Klinge, U., Klosterhalfen, B., Kasperk, R. and Schumpelick, V. (2001) Functional impairment and com- plaints following incisional hernia repair with different poly p ropyle ne meshes . Hernia, 5, 142–147. [41] Sugerman, H.J., Kellum Jr., J.M., Reines, H.D., DeMaria, E.J., Newsome, H.H. and Lowry, J.W. (1996) Greater risk of incisional hernia with morbidly obese than ster- oid-dependent patients and low recurrence with prefas- cial polypropylene mesh. Am J Surg, 171, 80–84. [42] Balen, E.M., Diez-Caballero, A., Hernandez-Lizoain, J. L., Pardo, F., Torramade, J.R., Regueira, F.M. and Cien- fuegos, J.A. (1998) Repair of ventral hernias with ex- panded polytetrafluoroethylene patch. Br J Surg, 85, 1415–1418. [43] Adloff, M. and Arnaud, J.P. (1987) Surgical management of large incisional hernias by an intraperitoneal Mersi- lene mesh and an aponeurotic graft. Surg Gynecol Obstet, 165, 204–206.

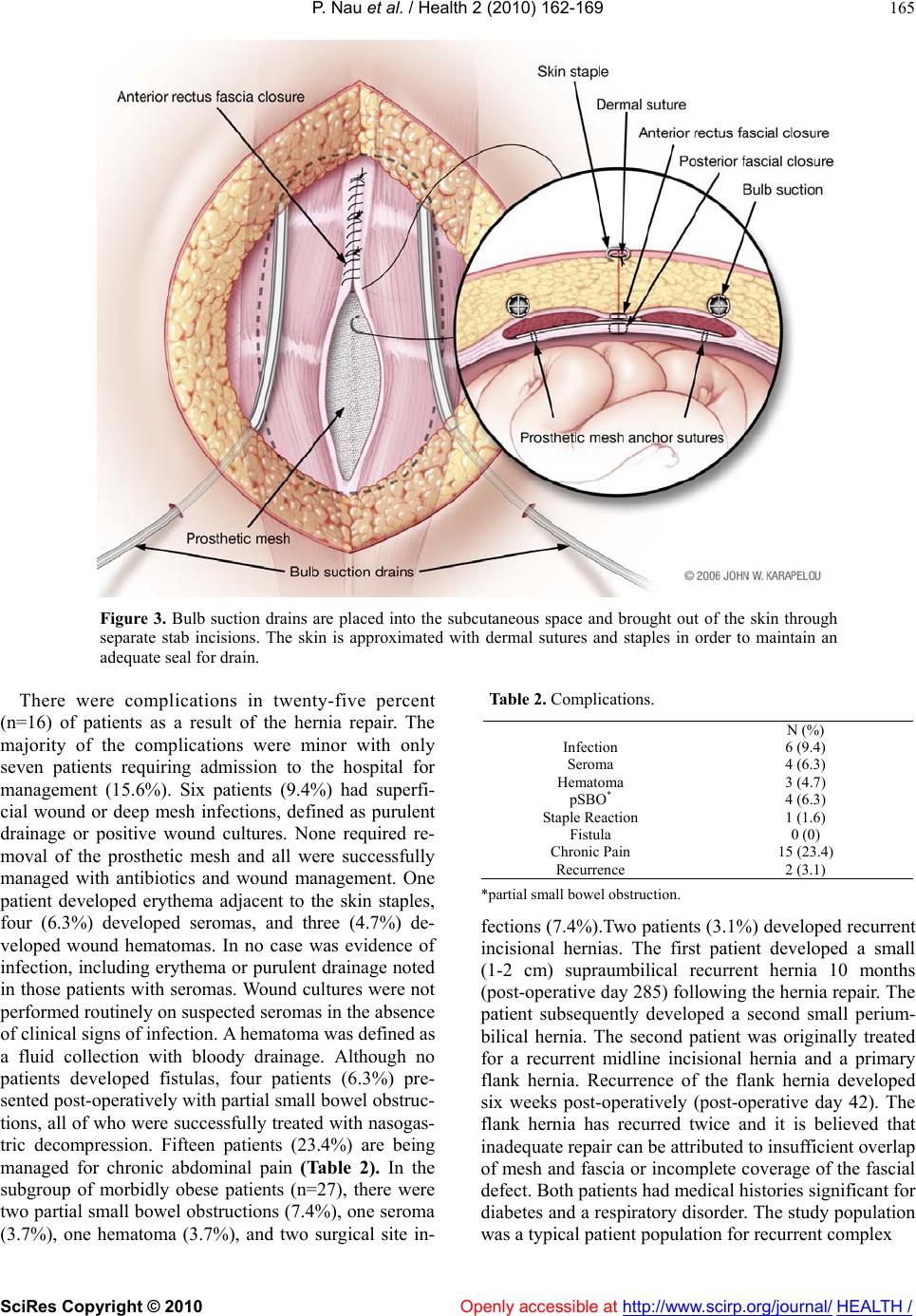

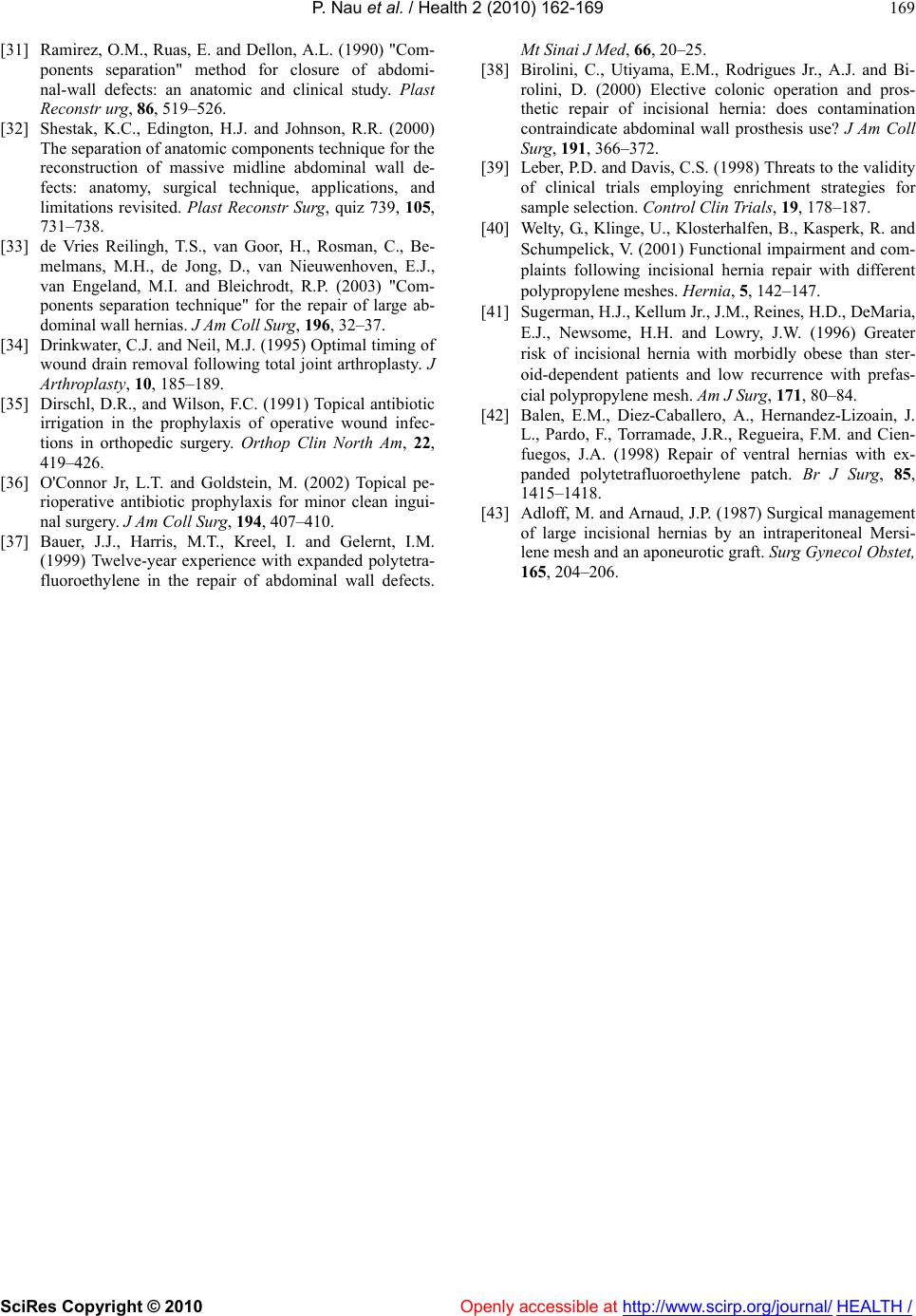

|