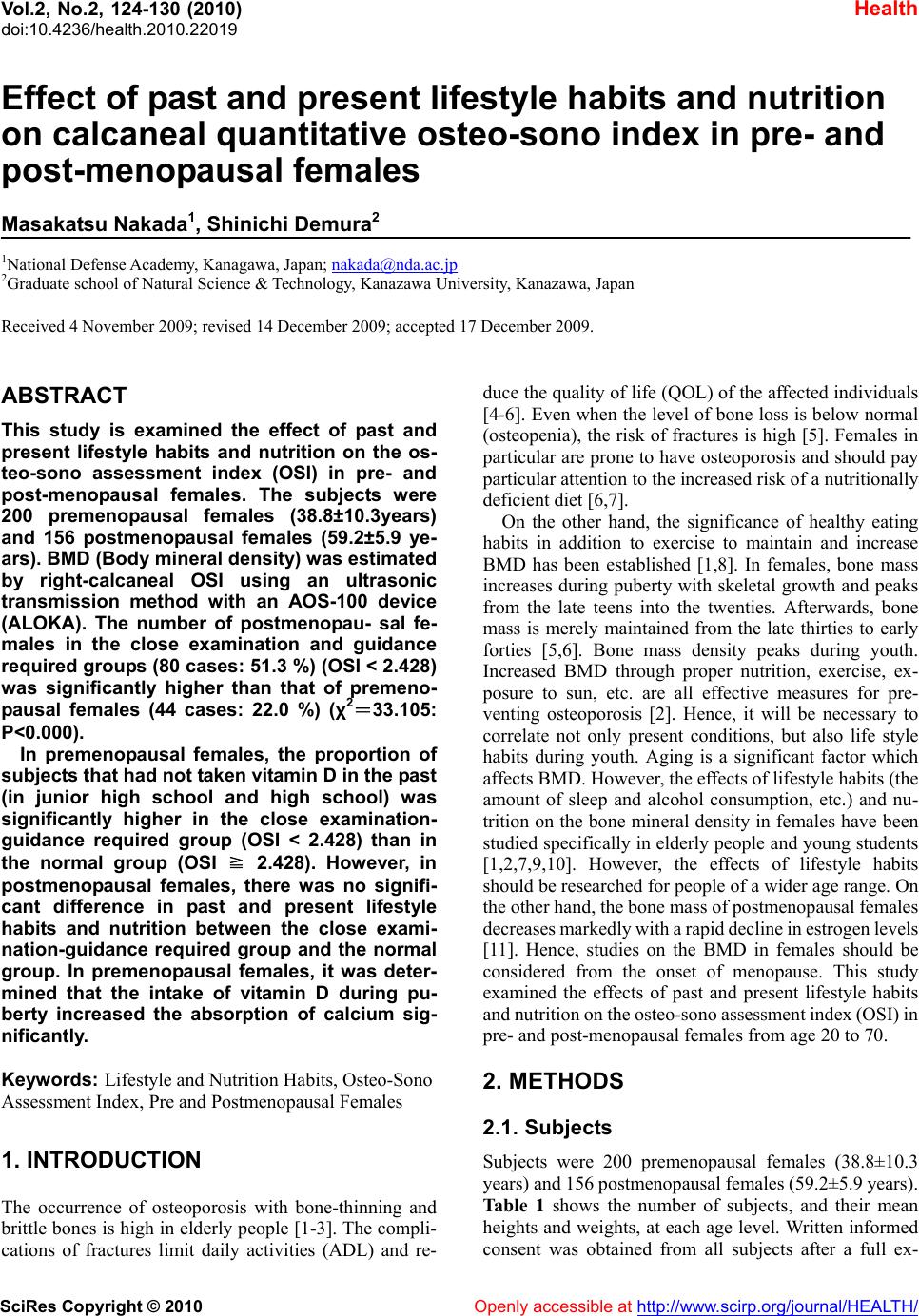

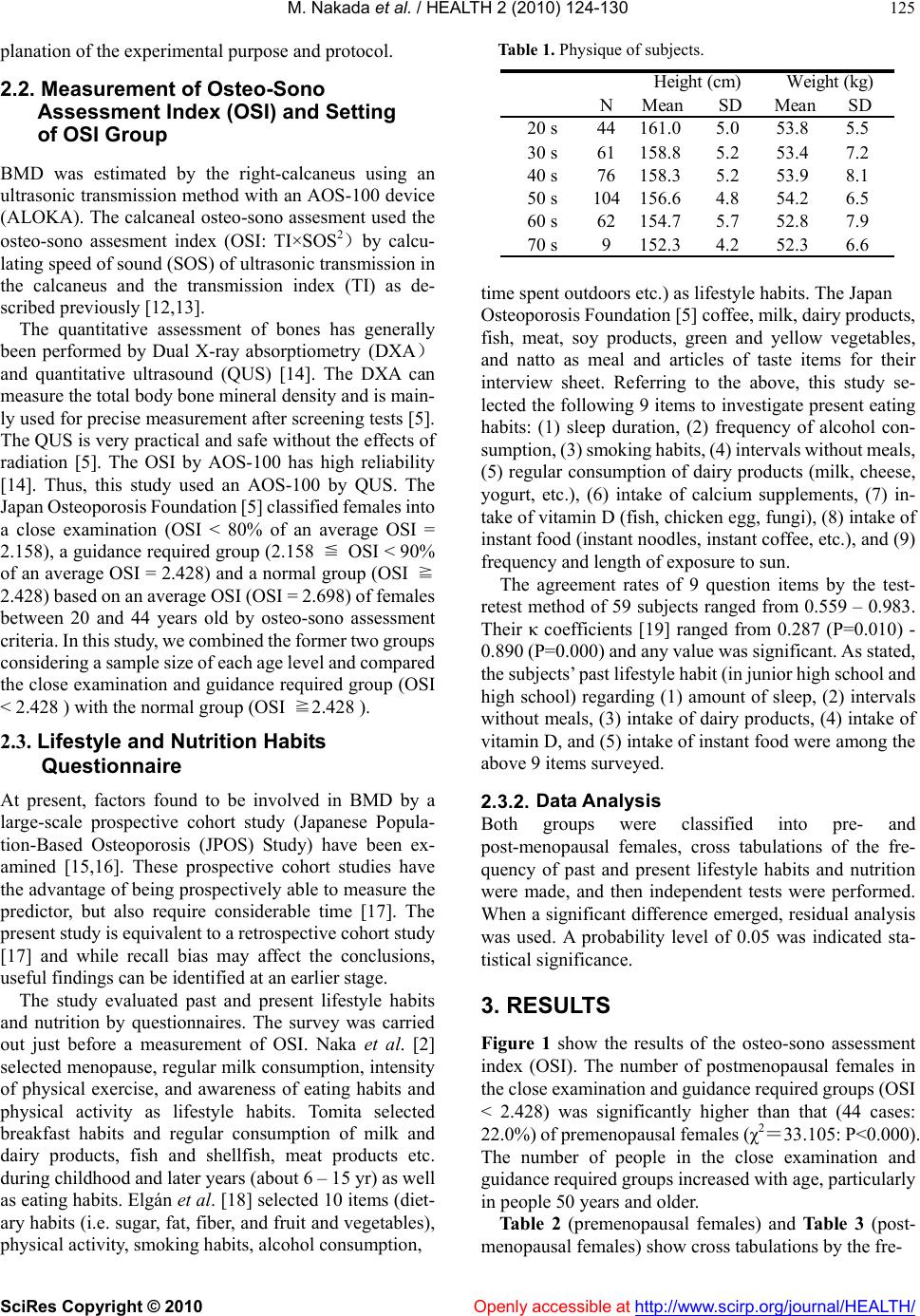

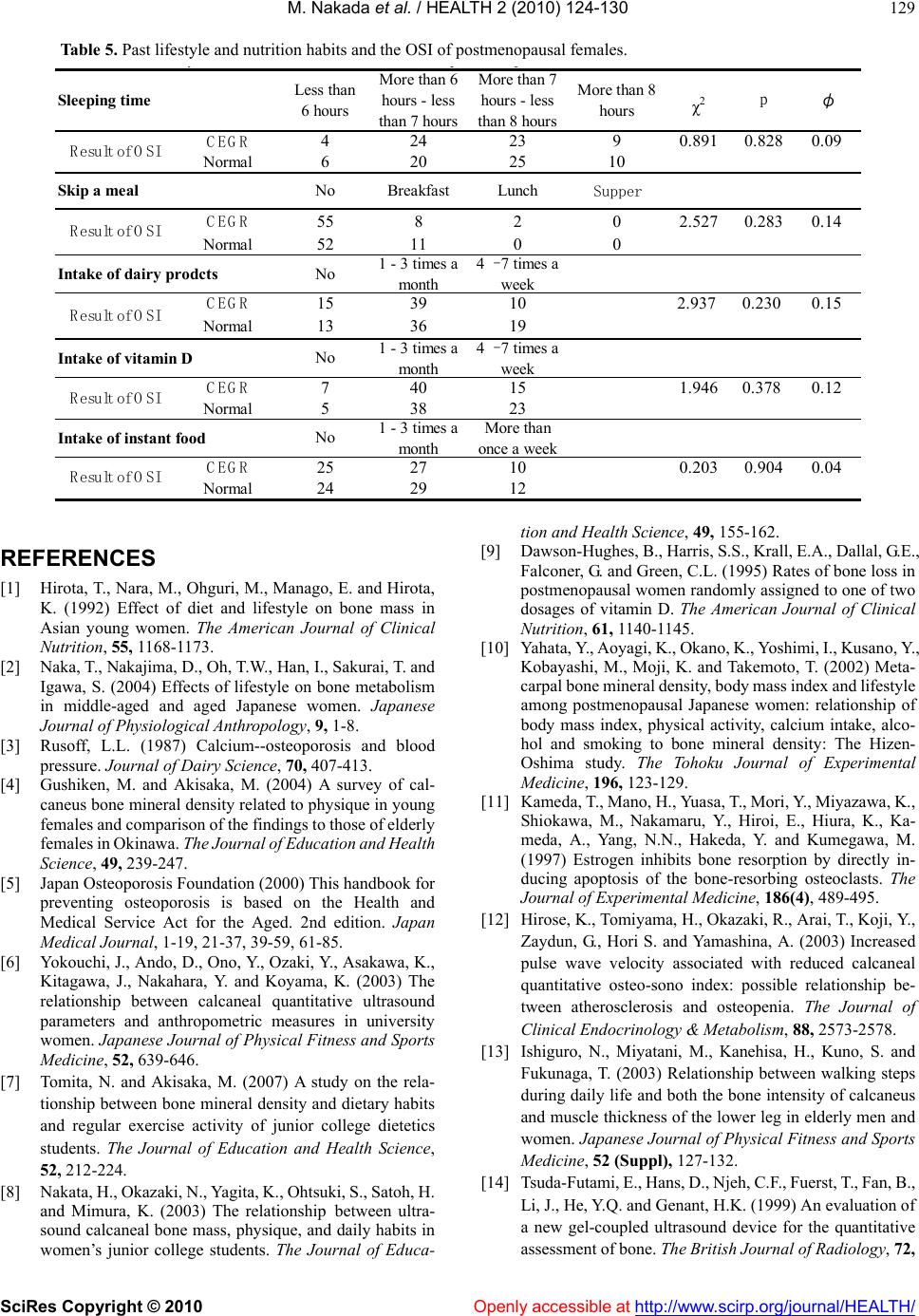

Vol.2, No.2, 124-130 (2010) doi:10.4236/health.2010.22019 SciRes Copyright © 2010 Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ Health Effect of past and present lifestyle habits and nutrition on calcaneal quantitative osteo-sono index in pre- and post-menopausal females Masakatsu Nakada1, Shinichi Demura2 1National Defense Academy, Kanagawa, Japan; nakada@nda.ac.jp 2Graduate school of Natural Science & Technology, Kanazawa University, Kanazawa, Japan Received 4 November 2009; revised 14 December 2009; accepted 17 December 2009. ABSTRACT This study is examined the effect of past and present lifestyle habits and nutrition on the os- teo-sono assessment index (OSI) in pre- and post-menopausal females. The subjects were 200 premenopausal females (38.8±10.3years) and 156 postmenopausal females (59.2±5.9 ye- ars). BMD (Body mineral density) was estimated by right-calcaneal OSI using an ultrasonic transmission method with an AOS-100 device (ALOKA). The number of postmenopau- sal fe- males in the close examination and guidance required groups (80 cases: 51.3 %) (OSI < 2.428) was significantly higher than that of premeno- pausal females (44 cases: 22.0 %) (χ2=33.105: P<0.000). In premenopausal females, the proportion of subjects that had not taken vitamin D in the past (in junior high school and high school) was significantly higher in the close examination- guidance required group (OSI < 2.428) than in the normal group (OSI ≧ 2.428). However, in postmenopausal females, there was no signifi- cant difference in past and present lifestyle habits and nutrition between the close exami- nation-guidance required group and the normal group. In premenopausal females, it was deter- mined that the intake of vitamin D during pu- berty increased the absorption of calcium sig- nificantly. Keywords: Lifestyle and Nutrition Habits, Osteo-Sono Assessment Index, Pre and Postmenopausal Females 1. INTRODUCTION The occurrence of osteoporosis with bone-thinning and brittle bones is high in elderly people [1-3]. The compli- cations of fractures limit daily activities (ADL) and re- duce the quality of life (QOL) of the affected individuals [4-6]. Even when the level of bone loss is below normal (osteopenia), the risk of fractures is high [5]. Females in particular are prone to have osteoporosis and should pay particular attention to the increased risk of a nutritionally deficient diet [6,7]. On the other hand, the significance of healthy eating habits in addition to exercise to maintain and increase BMD has been established [1,8]. In females, bone mass increases during puberty with skeletal growth and peaks from the late teens into the twenties. Afterwards, bone mass is merely maintained from the late thirties to early forties [5,6]. Bone mass density peaks during youth. Increased BMD through proper nutrition, exercise, ex- posure to sun, etc. are all effective measures for pre- venting osteoporosis [2]. Hence, it will be necessary to correlate not only present conditions, but also life style habits during youth. Aging is a significant factor which affects BMD. However, the effects of lifestyle habits (the amount of sleep and alcohol consumption, etc.) and nu- trition on the bone mineral density in females have been studied specifically in elderly people and young students [1,2,7,9,10]. However, the effects of lifestyle habits should be researched for people of a wider age range. On the other hand, the bone mass of postmenopausal females decreases markedly with a rapid decline in estrogen levels [11]. Hence, studies on the BMD in females should be considered from the onset of menopause. This study examined the effects of past and present lifestyle habits and nutrition on the osteo-sono assessment index (OSI) in pre- and post-menopausal females from age 20 to 70. 2. METHODS 2.1. Subjects Subjects were 200 premenopausal females (38.8±10.3 years) and 156 postmenopausal females (59.2±5.9 years). Table 1 shows the number of subjects, and their mean heights and weights, at each age level. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects after a full ex-  M. Nakada et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 124-130 SciRes Copyright © 2010 Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 125 planation of the experimental purpose and protocol. 2.2. Measurement of Osteo-Sono Assessment Index (OSI) and Setting of OSI Group BMD was estimated by the right-calcaneus using an ultrasonic transmission method with an AOS-100 device (ALOKA). The calcaneal osteo-sono assesment used the osteo-sono assesment index (OSI: TI×SOS2)by calcu- lating speed of sound (SOS) of ultrasonic transmission in the calcaneus and the transmission index (TI) as de- scribed previously [12,13]. The quantitative assessment of bones has generally been performed by Dual X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) and quantitative ultrasound (QUS) [14]. The DXA can measure the total body bone mineral density and is main- ly used for precise measurement after screening tests [5]. The QUS is very practical and safe without the effects of radiation [5]. The OSI by AOS-100 has high reliability [14]. Thus, this study used an AOS-100 by QUS. The Japan Osteoporosis Foundation [5] classified females into a close examination (OSI < 80% of an average OSI = 2.158), a guidance required group (2.158 ≦ OSI < 90% of an average OSI = 2.428) and a normal group (OSI ≧ 2.428) based on an average OSI (OSI = 2.698) of females between 20 and 44 years old by osteo-sono assessment criteria. In this study, we combined the former two groups considering a sample size of each age level and compared the close examination and guidance required group (OSI < 2.428 ) with the normal group (OSI ≧2.428 ). 2.3. Lifestyle and Nutrition Habits Questionnaire At present, factors found to be involved in BMD by a large-scale prospective cohort study (Japanese Popula- tion-Based Osteoporosis (JPOS) Study) have been ex- amined [15,16]. These prospective cohort studies have the advantage of being prospectively able to measure the predictor, but also require considerable time [17]. The present study is equivalent to a retrospective cohort study [17] and while recall bias may affect the conclusions, useful findings can be identified at an earlier stage. The study evaluated past and present lifestyle habits and nutrition by questionnaires. The survey was carried out just before a measurement of OSI. Naka et al. [2] selected menopause, regular milk consumption, intensity of physical exercise, and awareness of eating habits and physical activity as lifestyle habits. Tomita selected breakfast habits and regular consumption of milk and dairy products, fish and shellfish, meat products etc. during childhood and later years (about 6 – 15 yr) as well as eating habits. Elgán et al. [18] selected 10 items (diet- ary habits (i.e. sugar, fat, fiber, and fruit and vegetables), physical activity, smoking habits, alcohol consumption, Table 1. Physique of subjects. NMeanSD Mean SD 20 s44161.05.053.85.5 30 s61158.85.253.47.2 40 s76158.35.253.98.1 50 s104156.64.854.26.5 60 s62154.75.752.87.9 70 s9152.34.252.36.6 Height (cm)Weight (kg) time spent outdoors etc.) as lifestyle habits. The Japan Osteoporosis Foundation [5] coffee, milk, dairy products, fish, meat, soy products, green and yellow vegetables, and natto as meal and articles of taste items for their interview sheet. Referring to the above, this study se- lected the following 9 items to investigate present eating habits: (1) sleep duration, (2) frequency of alcohol con- sumption, (3) smoking habits, (4) intervals without meals, (5) regular consumption of dairy products (milk, cheese, yogurt, etc.), (6) intake of calcium supplements, (7) in- take of vitamin D (fish, chicken egg, fungi), (8) intake of instant food (instant noodles, instant coffee, etc.), and (9) frequency and length of exposure to sun. The agreement rates of 9 question items by the test- retest method of 59 subjects ranged from 0.559 – 0.983. Their κ coefficients [19] ranged from 0.287 (P=0.010) - 0.890 (P=0.000) and any value was significant. As stated, the subjects’ past lifestyle habit (in junior high school and high school) regarding (1) amount of sleep, (2) intervals without meals, (3) intake of dairy products, (4) intake of vitamin D, and (5) intake of instant food were among the above 9 items surveyed. 2.3.2. Data Analysis Both groups were classified into pre- and post-menopausal females, cross tabulations of the fre- quency of past and present lifestyle habits and nutrition were made, and then independent tests were performed. When a significant difference emerged, residual analysis was used. A probability level of 0.05 was indicated sta- tistical significance. 3. RESULTS Figure 1 show the results of the osteo-sono assessment index (OSI). The number of postmenopausal females in the close examination and guidance required groups (OSI < 2.428) was significantly higher than that (44 cases: 22.0%) of premenopausal females (χ2=33.105: P<0.000). The number of people in the close examination and guidance required groups increased with age, particularly in people 50 years and older. Table 2 (premenopausal females) and Table 3 (post- menopausal females) show cross tabulations by the fre-  M. Nakada et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 124-130 SciRes Copyright © 2010 Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 126 Table 2. Present lifestyle and nutrition habits and the OSI of premenopausal females. Sleeping timeLess than 6 hours More than 6 hours - less than 7 hours More than 7 hours - less than 8 hours More than 8 hours χ 2 pφ CEGR 10(-1.04) 29(2.39)4( -2.05 1( 0.96)7.891 0.048*0.20 Normal48(1.04) 71(-2.39)36 ( 2.05 1( -0.96) Alcohol intakeNo 1 - 3 times a month 1 - 3 times a wee nearly ever da CEGR 1986107.760.051 0.20 Normal5062 22 21 Smoking NoHave a habitQuit CEGR 35450.602 0.740.06 Normal 1271612 Skip a mealNoBreakfast LunchSupper CEGR 355001.664 0.6450.09 Normal 1251824 Intake of dairy prodctsNo 1 - 3 times a month 4 – 7 times a wee CEGR 320210.630.73 0.06 Normal 156279 Intake of Ca supplementNoRarely Continuous CEGR 33730.564 0.7540.05 Normal 1103114 Intake of vitamin DNo 1 - 3 times a wee 4 – 7 times a wee CEGR 525142.200 0.333 0.11 Normal 89454 Intake of instant foodNo 1 - 3 times a month More than once a wee CEGR 514251.816 0.4030.10 Normal 275671 Sunbathing No 1 - 3 times a wee More than 4 times a week CEGR 1415151.5570.459 0.09 Normal 396846 Note) CEGR:close examination or guidance required group, *:P<0.05, Result of OSI Result of OSI Result of OSI Result of OSI Result of OSI Result of OSI Result of OSI Result of OSI Result of OSI Number shown in parenthese is the Z score of residual analysis. 13.5 3.5 44.4 19.4 8.7 1.3 1.6 2.3 37.8 18.5 44.4 35.5 39.4 19.7 14.8 11.4 48. 7 78 11.1 45.2 51.9 65.8 83.6 86.4 0%20% 40% 60% 80%100% Postmenopausal Premenopausal 70 s 60 s 50 s 40 s 30 s 20 s close examination required guidance required normal Age and OSI group Figure 1. Result of osteo-sono assessment index (OSI). ency of OSI groups and the frequency of present lifestyle habits and nutrition. An independent test showed sig-  M. Nakada et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 124-130 SciRes Copyright © 2010 Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 127 nificant differences in the amount of sleep in the premenopausal group of females. However, the results of residual analysis showed no significant differences in any category. In postmenopausal females, there was no sig- nificant difference in any present lifestyle habits or nu- trition. Table 4 (premenopausal females) and Table 5 (post- menopausal females) show cross tabulations by the fre- quency of OSI groups and past lifestyle habits and nutri- tion (in junior high school and high school). An inde- pendent test showed significant differences in the amount of sleep and intake of vitamin D in the group of pre- menopausal females. The results of residual analysis showed significant differences in the intake of vitamin D, and there was a higher proportion of subjects taking no vitamin D in the close examination-guidance required group (z=2.77>2.64:p<0.05). In postmenopausal fe- males, there was no significant difference in past lifestyle habits and nutrition. 4. DISCUSSION The Japan Osteoporosis Foundation [5] set the level for close examination (OSI < 2.158) when using an AOS-100 device (ALOKA) as 0.8 - 1.0 % in people 40-year olds, and 5.2 -11.4 % in 50-year olds. In this study, they were respectively 1.3 % and 8.7 %. Hence, the level for close examination was considered to be standard. There were no differences in present lifestyle habits and nutrition by OSI level. Nutrition and eating habits in addition to exercise habits are important for maintaining and increasing BMD. Principal minerals for absorption of calcium are magnesium and Vitamin D [7]. We surveyed past and present consumption of dairy products and vi- tamin D excluding magnesium and present intake of calcium supplements. Lloyd et al. [20] reported that by increasing daily calcium intake from 80% of the recom- mended daily allowance to 110% via supplementation with calcium citrate malate resulted in significant in- creases in total body and spinal bone density in adoles- cent girls. The proportion of those test subjects taking no vitamin D (fish, chicken egg, fungi etc) was higher in the close examination-guidance required group than in the normal group. The considerable amount of time that elderly people spend indoors also decreases Vitamin D synthesis through the skin in addition to their intake of vitamin D [5]. Dawson-Hughes et al. [21] examined during a long-term (3-year) study that the proper intake of vitamin D with intake of calcium helps reduce the de- crease of BMD. Intake of sufficient calcium and vitamin D additionally promotes the absorption of calcium in the small intestines, maintains calcitriol in the blood, and prevents an increased parathyroid hormone (PTH) level. This contributes to a reduction of bone loss [5,21]. The absorption of calcium is supported by the intake of vita- min D during puberty (junior high school and high school age) which increases bone mass with skeletal growth which may be very important for increasing peak bone mass. On the other hand, there was no difference in the past or present lifestyle habits and nutrition in postmenopausal females between the close examination and guidance required groups and the normal group. Bone mass de- creases with age at the rate of about 3 % a year through a lack of estrogen even in normal postmenopausal females [22]. Elderly people may need to increase their daily requirement of calcium as their intestinal calcium ab- sorption decreases [23]. Hence, with increasing age and lack of estrogen, the bone metabolism of postmenopausal females is largely affected, thus obscuring the effect of past and present life habits on bone mass changes. In addition, because of the long interval since puberty for postmenopausal females, subsequent lifestyle habits (eating habits and exercise) may have a greater affect on BMD. Hence, a long-term study should be done consid- ering the BMD of youth. This study did not examine the effect of exercise stimulus. Sanada et al. [24] reportedly showed a signifi- cant relationship between calcaneal bone strength and the strength of triceps muscle in postmenopausal females. Bone mass increases by imposing the load of body mass on the lumbar spine. Thus, the bone structure of the lower limbs and thereby the bones of the upper and lower limbs and spine benefit from the mechanical muscle stimulus received from twisting, distortion, and towing. Therefore, BMD is the result of past and present exercise and life- style habits. 5. SUMMARY This study examined the effect of past and present life- style habits and nutrition on OSI in pre- and post- menopausal females from 20 to 70 years of age. 1) The number of postmenopausal females in the close examination and guidance required groups (80 cases: 51.3 %) (OSI < 2.428) was significantly higher than that of premenopausal females (44 cases: 22.0 %) (χ2=33.105: P<0.000). 2) In premenopausal females, the number of subjects who had not taken vitamin D in the past (in junior high school and high school) was significantly higher in a close examination-guidance required group (OSI < 2.428) than in the normal group (OSI ≧ 2.428). However, in postmenopausal females, there was no significant dif- ference in past and present lifestyle habits and nutrition between the two groups. 3) In premenopausal females, it was inferred that in- creased intake of vitamin D during puberty is important to increase the absorption of calcium.  M. Nakada et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 124-130 SciRes Copyright © 2010 Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 128 Table 3. Present lifestyle and nutrition habits and the OSI of postmenopausal females. Sleeping timeLess than 6 hours More than 6 hours - less than 7 hours More than 7 hours - less than 8 hours More than 8 hours χ 2 pφ CEGR 22371741.330 0.722 0.09 Normal 17 38192 Alcohol intakeNo 1 - 3 times a month 1 - 3 times a week nearly ever da CEGR 44168113.907 0.2720.16 Normal 43 8817 Smoking NoHave a habitQuit CEGR 68741.028 0.5980.08 Normal 63 67 Skip a mealNoBreakfast LunchSupper CEGR 713301.942 0.584 0.12 Normal 66311 Intake of dairy prodctsNo 1 - 3 times a month 4 – 7 times a week CEGR 429451.001 0.606 0.08 Normal 22548 Intake of Ca supplementNoRarely Continuous CEGR 5711102.349 0.309 0.12 Normal 60 511 Intake of vitamin DNo 1 - 3 times a week 4 – 7 times a week CEGR 740320.012 0.9940.01 Normal 73830 Intake of instant foodNo 1 - 3 times a month More than once a wee CEGR 2124332.787 0.2480.14 Normal 27 2422 Sunbathing No 1 - 3 times a week More than 4 times a wee CEGR 1231302.534 0.2820.13 Normal 10 2339 Result of OSI Result of OSI Result of OSI Result of OSI Result of OSI Result of OSI Result of OSI Result of OSI Result of OSI Table 4. Past lifestyle and nutrition and the OSI of premenopausal females. Sleeping timeLess than 6 hours More than 6 hours - less than 7 hours More than 7 hours - less than 8 hours More than 8 hour s χ 2 pφ CEGR 1(-1.96)10(-0.89)15(0.87)7(2.16)8.4710.037* 0.23 Normal 20(1.96) 48(0.89)46(-0.87) 10(-2.16) Skip a mealNoBreakfast LunchSupper CEGR 325001.225 0.2680.08 Normal 112 3100 Intake of dairy prodctsNo 1 - 3 times a mon th 4 – 7 times a week CEGR 420141.825 0.4020.10 Normal 16 6172 Intake of vitamin DNo 1 - 3 times a week 4 – 7 times a week CEGR 5(2.77*)22(0.17)8(-1.47)8.712 0.013*0.22 Normal 4(-2.77*) 87(-0.17)51(1.47) Intake of instant foodNo 1 - 3 times a mon th More than once a week CEGR 71980.710 0.7010.06 Normal 24 7944 Note) CEGR:close examination or uidance re uired rou *:P<0.05 Result of OSI Result of OSI Result of OSI Result of OSI Result of OSI Number shown in parentheses is the Z score of the residual analysis  M. Nakada et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 124-130 SciRes Copyright © 2010 http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/Openly accessible at 129 yle and nutrition habits and the OSI of postmenopausal females. Table 5. Past lifest Sleeping timeLess than 6 hours More than 6 hours - less than 7 hours More than 7 hours - less than 8 hours More than 8 hours χ 2 pφ CEGR 4242390.891 0.8280.09 Normal 6202510 Skip a mealNoBreakfast LunchSupper CEGR 558202.527 0.2830.14 Normal 52 1100 Intake of dairy prodctsNo 1 - 3 times a mo n th 4 – 7 times a wee CEGR 1539102.937 0.2300.15 Normal 13 3619 Intake of vitamin DNo 1 - 3 times a mo n th 4 – 7 times a wee CEGR 740151.9460.3780.12 Normal 53823 Intake of instant foodNo 1 - 3 times a mo n th More than once a wee CEGR 2527100.203 0.9040.04 Normal 24 2912 Result of OSI Result of OSI Result of OSI Result of OSI Result of OSI REFERENCES [1] Hirota, T., Nara, M., Ohguri, M., Manago, E. and Hirota, K. (1992) Effect of diet and lifestyle on bone mass in Asian young women. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 55, 1168-1173. [2] Naka, T., Nakajima, D., Oh, T.W., Han, I., Sakurai, T. and Igawa, S. (2004) Effects of lifestyle on bone metabolism in middle-aged and aged Japanese women. Japanese Journal of Physiological Anthropology, 9, 1-8. [3] Rusoff, L.L. (1987) Calcium--osteoporosis and blood pressure. Journal of Dairy Science, 70, 407-413. [4] Gushiken, M. and Akisaka, M. (2004) A survey of cal- caneus bone mineral density related to physique in young females and comparison of the findings to those of elderly females in Okinawa. The Journal of Education and Health Science, 49, 239-247. [5] Japan Osteoporosis Foundation (2000) This handbook for preventing osteoporosis is based on the Health and Medical Service Act for the Aged. 2nd edition. Japan Medical Journal, 1-19, 21-37, 39-59, 61-85. [6] Yokouchi, J., Ando, D., Ono, Y., Ozaki, Y., Asakawa, K., Kitagawa, J., Nakahara, Y. and Koyama, K. (2003) The relationship between calcaneal quantitative ultrasound parameters and anthropometric measures in university women. Japanese Journal of Physical Fitness and Sports Medicine, 52, 639-646. [7] Tomita, N. and Akisaka, M. (2007) A study on the rela- tionship between bone mineral density and dietary habits and regular exercise activity of junior college dietetics students. The Journal of Education and Health Science, 52, 212-224. [8] Nakata, H., Okazaki, N., Yagita, K., Ohtsuki, S., Satoh, H. and Mimura, K. (2003) The relationship between ultra- sound calcaneal bone mass, physique, and daily habits in women’s junior college students. The Journal of Educa- tion and Health Science, 49, 155-162. [9] Dawson-Hughes, B., Harris, S.S., Krall, E.A., Dallal, G.E., Falconer, G. and Green, C.L. (1995) Rates of bone loss in postmenopausal women randomly assigned to one of two dosages of vitamin D. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 61, 1140-1145. [10] Yahata, Y., Aoyagi, K., Okano, K., Yoshimi, I., Kusano, Y., Kobayashi, M., Moji, K. and Takemoto, T. (2002) Meta- carpal bone mineral density, body mass index and lifestyle among postmenopausal Japanese women: relationship of body mass index, physical activity, calcium intake, alco- hol and smoking to bone mineral density: The Hizen- Oshima study. The Tohoku Journal of Experimental Medicine, 196, 123-129. [11] Kameda, T., Mano, H., Yuasa, T., Mori, Y., Miyazawa, K., Shiokawa, M., Nakamaru, Y., Hiroi, E., Hiura, K., Ka- meda, A., Yang, N.N., Hakeda, Y. and Kumegawa, M. (1997) Estrogen inhibits bone resorption by directly in- ducing apoptosis of the bone-resorbing osteoclasts. The Journal of Experimental Medicine, 186(4), 489-495. [12] Hirose, K., Tomiyama, H., Okazaki, R., Arai, T., Koji, Y., Zaydun, G., Hori S. and Yamashina, A. (2003) Increased pulse wave velocity associated with reduced calcaneal quantitative osteo-sono index: possible relationship be- tween atherosclerosis and osteopenia. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 88, 2573-2578. [13] Ishiguro, N., Miyatani, M., Kanehisa, H., Kuno, S. and Fukunaga, T. (2003) Relationship between walking steps during daily life and both the bone intensity of calcaneus and muscle thickness of the lower leg in elderly men and women. Japanese Journal of Physical Fitness and Sports Medicine, 52 (Suppl), 127-132. [14] Tsuda-Futami, E., Hans, D., Njeh, C.F., Fuerst, T., Fan, B., Li, J., He, Y.Q. and Genant, H.K. (1999) An evaluation of a new gel-coupled ultrasound device for the quantitative assessment of bone. The British Journal of Radiology, 72,  M. Nakada et al. / HEALTH 2 (2010) 124-130 SciRes Copyright © 2010 Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 130 691-700. [15] Ikeda, Y., Iki, M., Morita, A., Kajita, E., Kagamimori, S., Kagawa, Y. and Yoneshima, H. (2006) Intake of fer- mented soybeans, natto, is associated with reduced bone loss in postmenopausal women: Japanese Popula- tion-Based Osteoporosis (JPOS) Study. The Journal of Nutrition, 136, 1323-1328. [16] Morita, A., Iki, M., Dohi, Y., Ikeda, Y., Kagamimori, S., Kagawa, Y., Matsuzaki, T., Yoneshima, H. and Marumo, F. (2004) Prediction of bone mineral density from vitamin D receptor polymorphisms is uncertain in representative samples of Japanese Women. The Japanese Popula- tion-based Osteoporosis (JPOS) Study. International Journal of Epidemiology, 33, 979-988. [17] Demura, S. (2007) Health and sports science research method. Kyorin-shoin, Tokyo, 65-86. [18] Elgán, C. and Fridlund, B. (2006) Bone mineral density in relation to body mass index among young women: a prospective cohort study. International Journal of Nurs- ing Studies, 43, 663-672. [19] Cohen J (1988) Statistical power analysis for the behav- ioral sciences 2nd. Lawrence Erlbaum Assoc Inc. [20] Lloyd, T., Andon, M.B., Rollings, N., Martel, J.K., Landis J.R., Demers, L.M., Eggli, D.F., Kieselhorst, K. and Kulin, H.E. (1993) Calcium supplementation and bone mineral density in adolescent girls. The Journal of the American Medical Association, 270, 841-844. [21] Dawson-Hughes, B., Harris, S.S., Krall, E.A. and Dallal, G.E. (1997) Effect of calcium and vitamin D supplemen- tation on bone density in men and women 65 years of age or older. The New England Journal of Medicine, 337, 670-676. [22] Dawson-Hughes, B. (1996) Calcium and vitamin D nu- tritional needs of elderly women. The Journal of Nutrition 126, 1165s-1167s. [23] Gallagher, J.C., Riggs, B.L., Eisman, J., Hamstra, A., Arnaud, S.B. and DeLuca, H.F. (1979) Intestinal calcium absorption and serum vitamin D metabolites in normal subjects and osteoporotic patients: effect of age and die- tary calcium. The Journal of Clinical Investigation, 64, 729-736. [24] Sanada, K., Sato, S., Kambe, Y., Kuchiki, T., Bunya, T. and Ebashi, H.(1999) Relationships between the gas- trocnemius or soleus muscle thickness and the calcaneal bone stiffness in post menopausal women. Japanese Journal of Physical Fitness and Sports Medicine, 48, 291-300.

|