Applied Mathematics

Vol.5 No.16(2014), Article ID:49468,11 pages

DOI:10.4236/am.2014.516244

Asymptotic Harmonic Behavior in the Prime Number Distribution

Maurice H.P.M. van Putten

Sejong University, Seoul, South Korea

Email:mvp@sejong.ac.kr

Copyright © 2014 by author and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received 16 June 2014; revised 19 July 2014; accepted 29 July 2014

Abstract

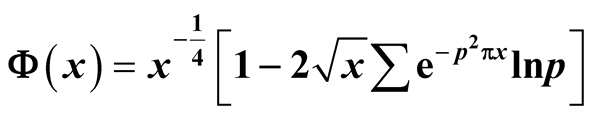

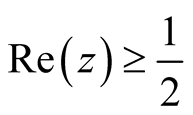

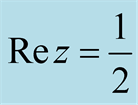

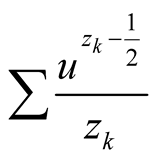

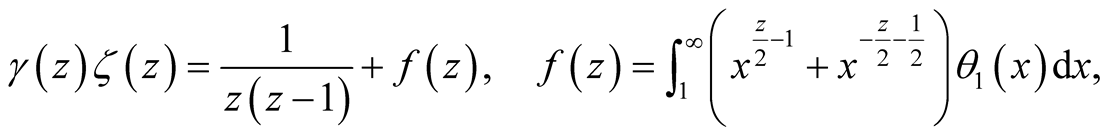

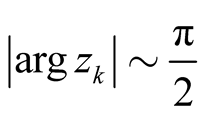

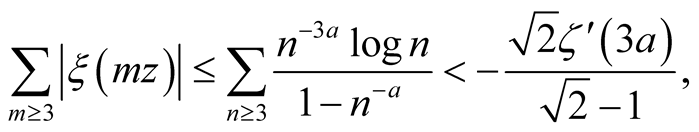

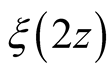

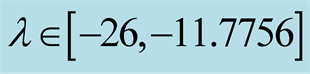

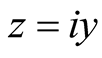

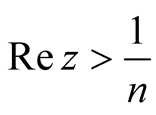

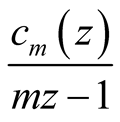

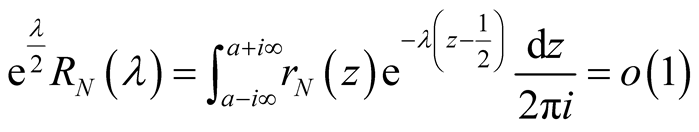

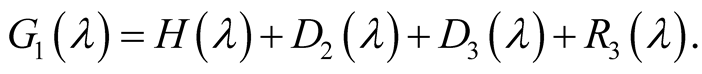

We consider

on

on , where the sum

is over all primes

, where the sum

is over all primes . If

. If

is bounded on

is bounded on , then the Riemann

hypothesis is true or there are infinitely many zeros

, then the Riemann

hypothesis is true or there are infinitely many zeros . The first 21 zeros

give rise to asymptotic harmonic behavior in

. The first 21 zeros

give rise to asymptotic harmonic behavior in

defined by the prime numbers up to one trillion.

defined by the prime numbers up to one trillion.

Keywords: Prime Number Distribution,Summation,Regularization

1. Introduction

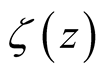

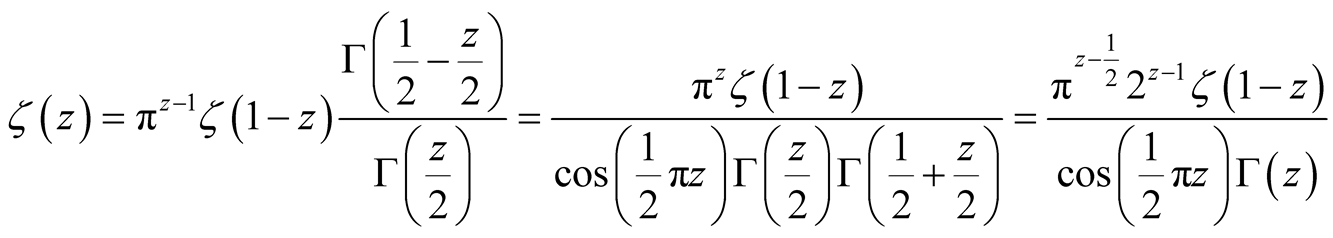

The Riemann-zeta function is the analytic extension of

(1)

(1)

where Euler’s identity on the right hand side expresses the relation of the integers

to the primes. The zeros

of Riemann’s analytic continuation of (1) comprise the negative even integers,

of Riemann’s analytic continuation of (1) comprise the negative even integers, , and an infinite number of nontrivial zeros

, and an infinite number of nontrivial zeros

in the strip

in the strip .

.

A general approach to find zeros is by continuation[1]

. If

is a starting point of a path

is a starting point of a path

with tangent

with tangent ,

,

(2)

(2)

then the endpoint

is a zero of

is a zero of , all of which are isolated.

All known nontrivial zeros satisfy

, all of which are isolated.

All known nontrivial zeros satisfy to within numerical precision, the first three of which are

to within numerical precision, the first three of which are ,

,

By the symmetry

By the symmetry

(3)

(3)

it suffices to study zeros in the half plane .

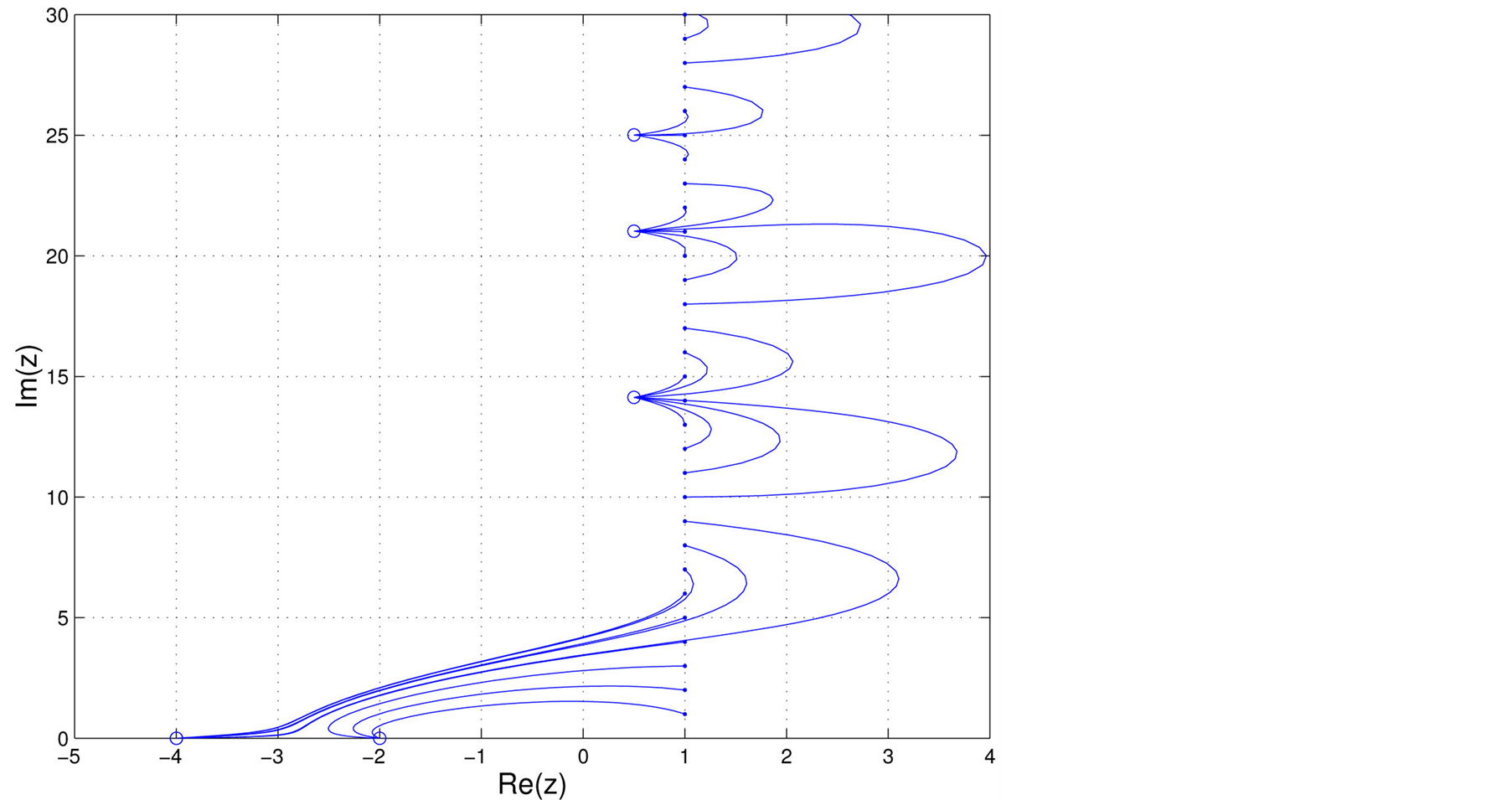

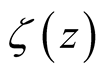

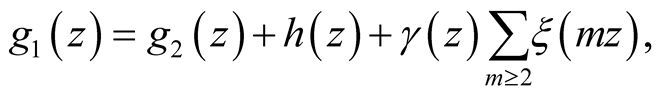

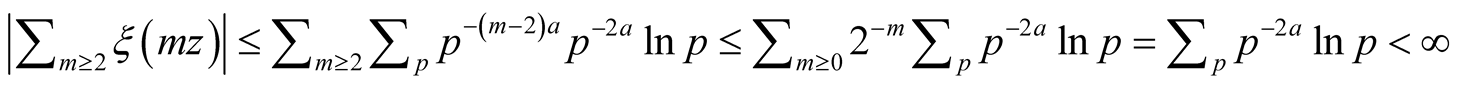

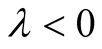

Figure 1illustrates root finding by (2) for the first few zeros.

.

Figure 1illustrates root finding by (2) for the first few zeros.

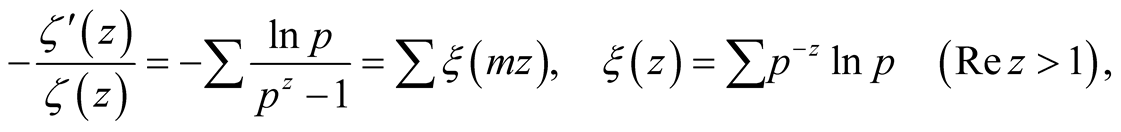

Continuation (2) is determined by the prime numbers, since

(4)

(4)

whereby

(5)

(5)

The poles of

at the zeros are therefore expressed by the prime number distribution.

at the zeros are therefore expressed by the prime number distribution.

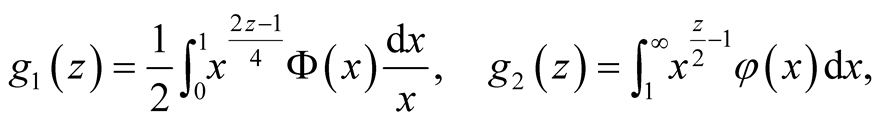

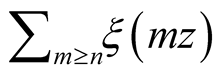

In this paper, we study the distribution of zeros

by Fourier analysis of the function

by Fourier analysis of the function

(6)

(6)

on , where

, where

(7)

(7)

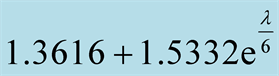

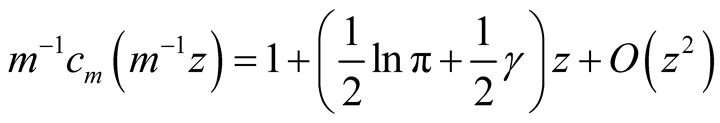

with summation over all primes. In what follows, we put

(8)

(8)

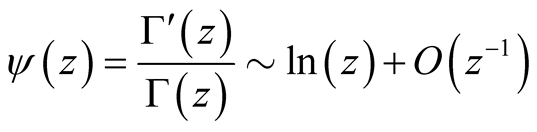

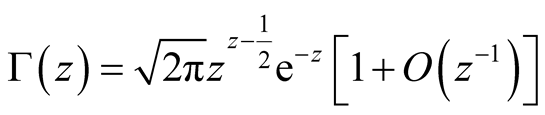

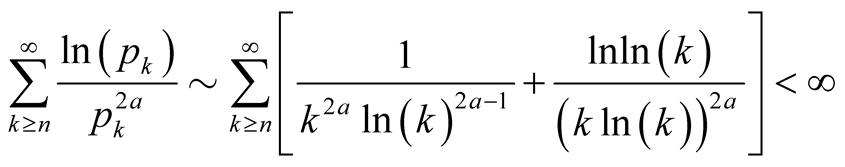

The

are absolutely summable by Stirling’s formula and

the asymptotic distribution of

are absolutely summable by Stirling’s formula and

the asymptotic distribution of .

.

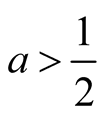

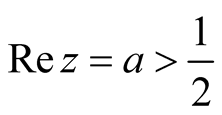

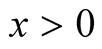

Theorem 1.1. In the limit as

becomes small, we have the asymptotic behavior

becomes small, we have the asymptotic behavior

(9)

(9)

In (9), is evidently unbounded in the limit as

is evidently unbounded in the limit as

approaches zero whenever a finite number of zeros

approaches zero whenever a finite number of zeros

exists off the critical line .

.

Corollary 1.2. If

is bounded, then the Riemann hypothesis is true or there are infinitely many zeros

is bounded, then the Riemann hypothesis is true or there are infinitely many zeros

.

.

A similar relation between the distribution of

and the primes is [2]

[3]

and the primes is [2]

[3]

(10)

(10)

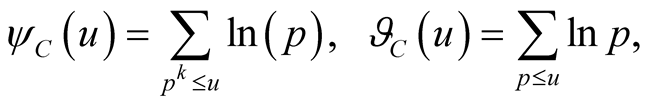

based on the Chebyshev functions

Figure 1.Shown are the

trajectories of continuation

in the complex plane

in the complex plane

by numerical integration of (2) with initial data

by numerical integration of (2) with initial data

indicated by small dots on

indicated by small dots on . Continuation produces

roots indicated by open circles, defined by finite endpoints of

. Continuation produces

roots indicated by open circles, defined by finite endpoints of

in the limit as

in the limit as

approaches infinity. The roots produced by the choice of initial data are the first

three on

approaches infinity. The roots produced by the choice of initial data are the first

three on

and −2 and −4 of the trivial roots.

and −2 and −4 of the trivial roots.

(11)

(11)

where the sum is over all primes

and integers

and integers . In (9),

. In (9), has a normalization by

has a normalization by

according to and

according to and

is absolutely convergent for all

is absolutely convergent for all , whereas in (10)

, whereas in (10)

is normalized by

is normalized by

and the sum

and the sum

is not absolutely convergent. Similar to Corollary

1.2, the left hand side of (10) will be bounded in the limit of large

is not absolutely convergent. Similar to Corollary

1.2, the left hand side of (10) will be bounded in the limit of large

if the Riemann hypothesis is true.

if the Riemann hypothesis is true.

Section 2 presents some preliminaries on . Section 3 gives an integral

representation of

. Section 3 gives an integral

representation of

and a discussion on its singularity at

and a discussion on its singularity at . In Section 4, Cauchy’s

integral formula is applied to derive a sum of residues associated with the

. In Section 4, Cauchy’s

integral formula is applied to derive a sum of residues associated with the . The proof Theorem 1.1

follows from a Fourier transform and asymptotic analysis (Section 5). In Section

6, we illustrate a direct evaluation of

. The proof Theorem 1.1

follows from a Fourier transform and asymptotic analysis (Section 5). In Section

6, we illustrate a direct evaluation of

using the primes up to one trillion, showing harmonic behavior arising from

using the primes up to one trillion, showing harmonic behavior arising from

by the first few zeros

by the first few zeros . We summarize our findings

in Section 7.

. We summarize our findings

in Section 7.

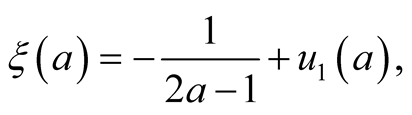

2.Background

Our analysis begins with some known properties of

in, e.g.,[4] -[9]

.

in, e.g.,[4] -[9]

.

Riemann obtained an analytic extension of

by expressing

by expressing

in terms of

in terms of ,

,

(12)

(12)

where

(13)

(13)

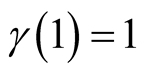

Here, satisfies

satisfies

as

as

approaches zero by the identity

approaches zero by the identity

for the Jacobi function

for the Jacobi function

1. On

1. On , it obtains

the meromorphic expression (e.g. Borwein et al., 2006)

, it obtains

the meromorphic expression (e.g. Borwein et al., 2006)

(14)

(14)

which gives a maximal analytic continuation of

and shows a simple pole at

and shows a simple pole at

with residue 1.

with residue 1.

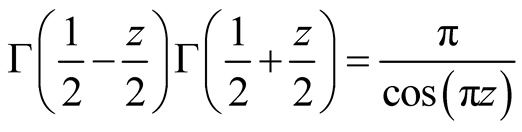

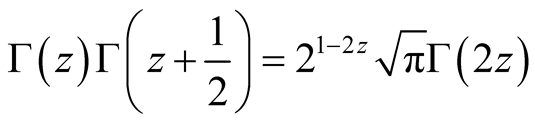

Riemann further introduced the symmetric form ,

, satisfying

satisfying

, whereby

, whereby

(15)

(15)

using

and

and . Along

. Along ,

, is nonvanishing [10] -[13]

, allowing

is nonvanishing [10] -[13]

, allowing

(16)

(16)

in terms of the digamma function

(17)

(17)

in the limit of large .

.

Lemma 2.1. In the limit of large , the logarithmic

derivative of

, the logarithmic

derivative of

satisfies

satisfies

(18)

(18)

Proof. The result follows from (17) and (16). Lemma 2.2.Along the line , we have the asymptotic expansion

, we have the asymptotic expansion in the limit of large

in the limit of large , whereby the

, whereby the

are absolutely summable.

are absolutely summable.

Proof.Recall (8) and the asymptotic expansion

with a branch cut along the negative real axis. In the limit of large

with a branch cut along the negative real axis. In the limit of large ,

, , and hence

, and hence , since

, since

as

as

becomes large. Hence,the

are absolutely summable. Numerically, their sum is small,

are absolutely summable. Numerically, their sum is small,

based on a large number of known zeros .Lemma 2.3. In the

limit of large

.Lemma 2.3. In the

limit of large , we have

, we have

(19)

(19)

Proof. By Lemma 2.1-2.2, we have

(20)

(20)

(21)

(21)

on

for some positive constants

for some positive constants .,

.,

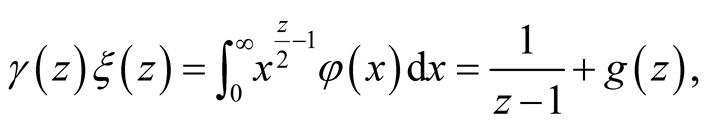

3.An IntegralRepresentation of

Following the same steps leading to the Riemann integral for , we have

, we have

(22)

(22)

where

absorbs the simple pole in

absorbs the simple pole in

at

at

due to the simple pole in

due to the simple pole in

at

at , leaving

, leaving

analytic at

analytic at . Following a decomposition

. Following a decomposition ,

,

(23)

(23)

and substitution ,

, appears as the Laplace transforms

appears as the Laplace transforms

(24)

(24)

These integral expressions allow continuations to , respectively, the entire

complex plane.

, respectively, the entire

complex plane.

Lemma 3.1. Analytic extension of

extends to

extends to .

.

Proof. With , the second term on the right hand

side in (5) satisfies

, the second term on the right hand

side in (5) satisfies

(25)

(25)

which is bounded in . Since the second term

. Since the second term

in (5) is analytic in

in (5) is analytic in , it follows that

, it follows that

in is analytic on

in is analytic on . Following (5) as

. Following (5) as

approaches

approaches

from the right, we have

from the right, we have

(26)

(26)

where

is analytic at

is analytic at . By (22), as

. By (22), as

approaches

approaches

from the right, we have

from the right, we have

(27)

(27)

where

is analytic about

is analytic about .

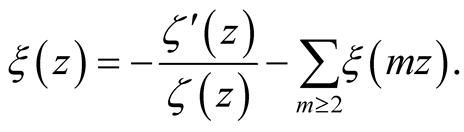

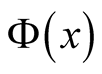

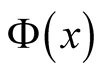

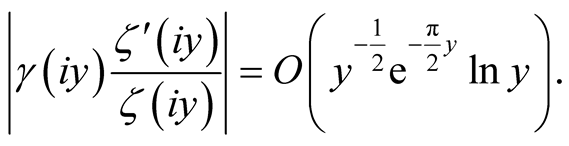

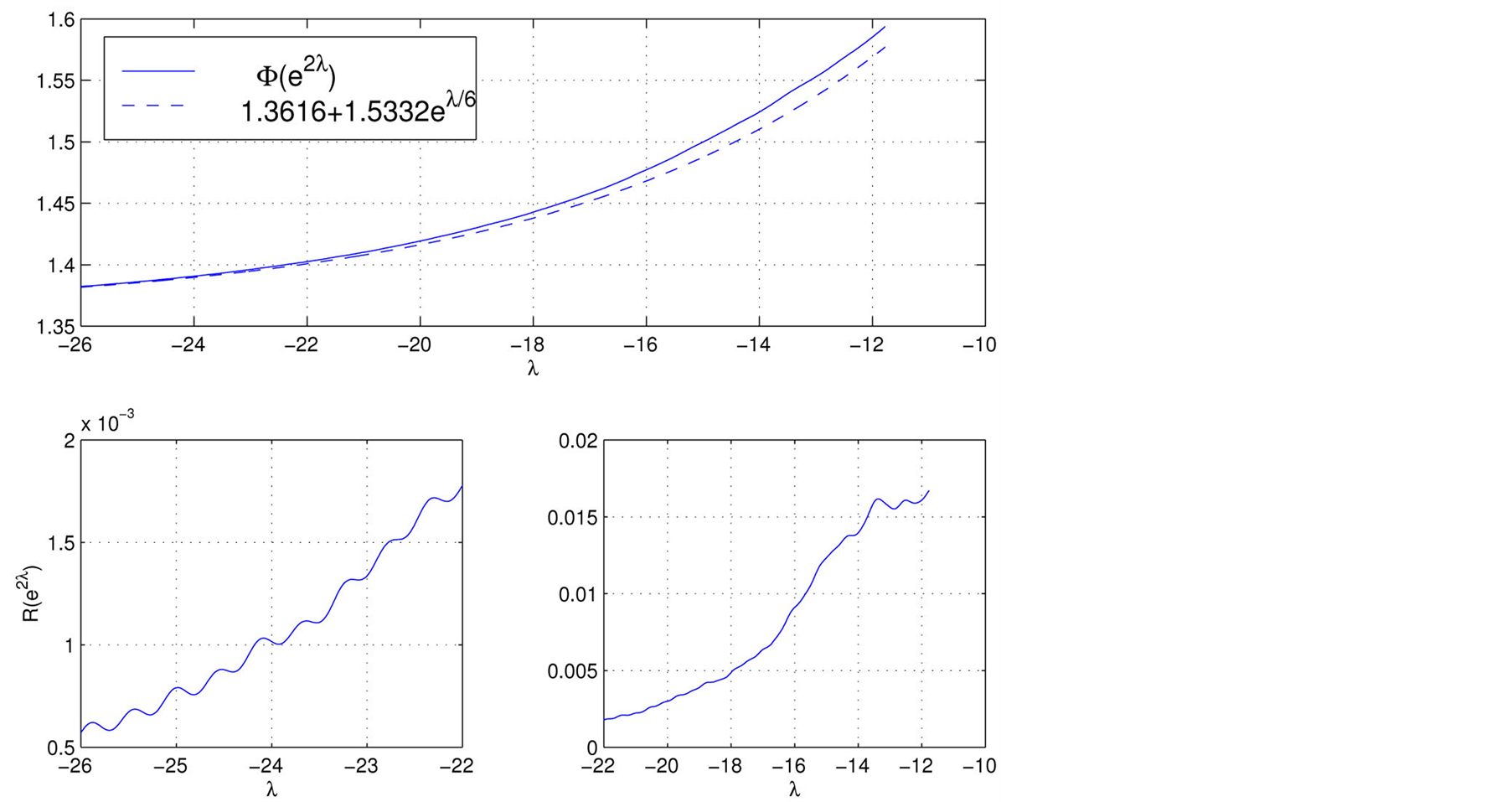

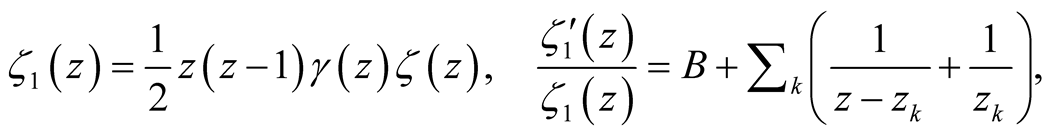

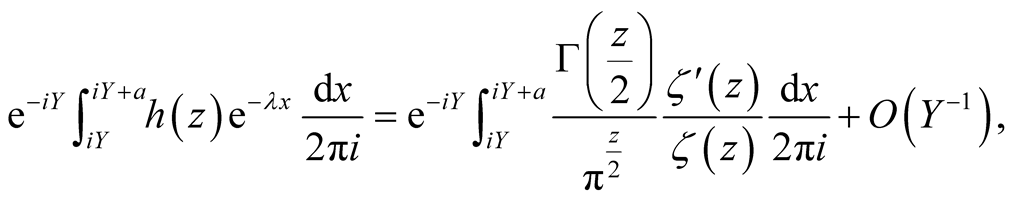

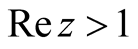

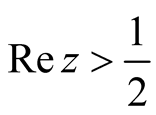

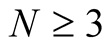

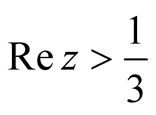

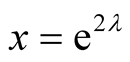

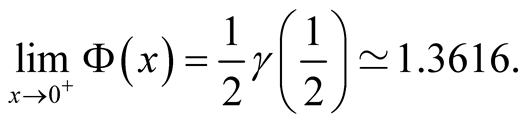

Figure 2 shows a numerical evaluation of

.

Figure 2 shows a numerical evaluation of

for small

for small

evaluated for the 37.6 billion primes up to one trillion, allowing

evaluated for the 37.6 billion primes up to one trillion, allowing

down to

down to

in view of the requirement for an accurate truncation in

in view of the requirement for an accurate truncation in

as defined by (7). The result shows asymptotic harmonic behavior in the limit as

as defined by (7). The result shows asymptotic harmonic behavior in the limit as

becomes small.

becomes small.

If the integral

Figure 2.The top window shows

on

on

and its leading order approximation

and its leading order approximation . The asymptotic harmonic

behavior is apparent in the residual difference (52) between the two, shown in the

bottom two windows, including the period of 2.2496 in

. The asymptotic harmonic

behavior is apparent in the residual difference (52) between the two, shown in the

bottom two windows, including the period of 2.2496 in associated with the first zero

associated with the first zero .

.

(28)

(28)

is absolutely convergent as

approaches zero, e.g., when

approaches zero, e.g., when

is of one sign in some neighborhood of

is of one sign in some neighborhood of

, as in the numerical evaluation shown in Figure 2, then

, as in the numerical evaluation shown in Figure 2, then

has an analytic extension into

has an analytic extension into

with no singularities, implying the absence of

in this region. However, this requires information on the point wise behavior of

in this region. However, this requires information on the point wise behavior of , which goes beyond the relatively weaker integrability

property (23).

, which goes beyond the relatively weaker integrability

property (23).

To make a step in this direction, we next apply a linear transform to (5) to derive

the asymptotic behavior of

in terms of the distribution

in terms of the distribution .

.

4.A Sum of Residues ZAssociated with the Non-Trivial Zeros

Consider

(29)

(29)

and its Fourier transform

(30)

(30)

Lemma 4.1. has a simple pole at

has a simple pole at

with residue 1 and simple poles at each of the nontrivial zeros

with residue 1 and simple poles at each of the nontrivial zeros

of

of

with residue

with residue .

.

Proof. We have (e.g. Borwein et al. 2006)

(31)

(31)

where

is a constant, so that

is a constant, so that

(32)

(32)

Here

(33)

(33)

where

denotes the digamma function as before, includes contributions from the logarithmic

derivative of the factor to

denotes the digamma function as before, includes contributions from the logarithmic

derivative of the factor to

in (31), whose singularities are restricted to the trivial zeros of

in (31), whose singularities are restricted to the trivial zeros of . We now consider

the Fourier integral over

. We now consider

the Fourier integral over

as part of contour integration closed over

as part of contour integration closed over

and

and .

.

Proposition 4.2. The Fourier transform of

over

over

satisfies

satisfies

(34)

(34)

in the limit of large .

.

Proof. Integration over

gives

gives

(35)

(35)

where we choose

to be between two consecutive values of

to be between two consecutive values of . We have

. We have

(36)

(36)

In the limit as

approaches infinity,

approaches infinity, approaches zero and

approaches zero and

becomes small by Lemma 2.2., whence

becomes small by Lemma 2.2., whence

(37)

(37)

Next, integration over

with a small semicircle around

with a small semicircle around

obtains an

obtains an

result in the limit of large

result in the limit of large

by application of Lemma 2.1-2.3 and the Riemann-Lebesgue Lemma. The result now follows

in the limit as

by application of Lemma 2.1-2.3 and the Riemann-Lebesgue Lemma. The result now follows

in the limit as

approaches infinity, taking into account the residue sum

approaches infinity, taking into account the residue sum

associated with the

associated with the

and absolute summability of the

and absolute summability of the . ,

. ,

5.Proof of Theorem 1.1

Multiplying (5) by , we have

, we have

(38)

(38)

that is, by (22) and (29),

(39)

(39)

We thus consider

(40)

(40)

which ab initio is defined on

by Euler’s identity with Fourier transform

by Euler’s identity with Fourier transform

(41)

(41)

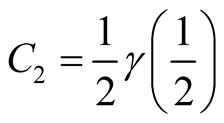

Turning to the right hand side of (40), we consider the coefficients

(42)

(42)

Here, since

since . In particular,

. In particular, and

and

has a well defined limit and

has a well defined limit and

in the limit as

in the limit as

becomes arbitrarily large.

becomes arbitrarily large.

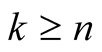

Lemma 5.1. The sum

is well-defined on

is well-defined on .

.

Proof. The result follows from the case . By the Prime Number

Theorem,

. By the Prime Number

Theorem, , whereby summation over the tails

, whereby summation over the tails

satisfy

satisfy

(43)

(43)

whenever . Hence, for

. Hence, for ,

, whenever

whenever . It follows that

. It follows that

(44)

(44)

on .Lemma 5.2.For any

.Lemma 5.2.For any , the Fourier

transform of

, the Fourier

transform of

over

over

satisfies

satisfies

(45)

(45)

Proof. The Fourier integral can be obtained in a contour integration with closure

over

and the edges

and the edges

for large

for large . In the

notation (42), it obtains a residue

. In the

notation (42), it obtains a residue

at , since

, since , whence

, whence

(46)

(46)

The integral (46) exists by virtue of a removable singularity of

at

at . It asymptotically decays to zero for large

. It asymptotically decays to zero for large

when

when

by the Riemann-Lebesgue Lemma. We now consider (40) with (22),

by the Riemann-Lebesgue Lemma. We now consider (40) with (22),

(47)

(47)

with a remainder

(48)

(48)

Lemma 5.3. For , the Fourier transform

, the Fourier transform

(49)

(49)

in the limit of large .

.

Proof. Since

is analytic in

is analytic in , we are at liberty

to consider the transform

, we are at liberty

to consider the transform

on

on

. The result follows from the Riemann-Lebesgue

Lemma. Proof of Theorem 1.1. The Fourier transform of (47) is

. The result follows from the Riemann-Lebesgue

Lemma. Proof of Theorem 1.1. The Fourier transform of (47) is

(50)

(50)

By Proposition 4.2 and Lemmas 5.1-5.2, we have

(51)

(51)

With , Theorem 1.1 now follows. ,

, Theorem 1.1 now follows. ,

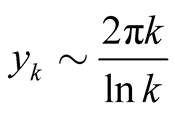

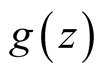

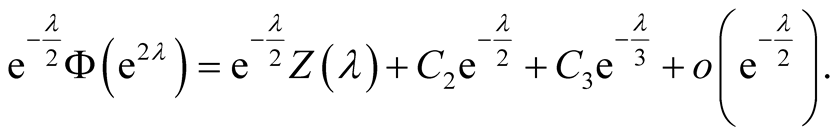

6.Numerical Illustration of Asymptotic Harmonic Behavior

The harmonic behavior emerges in

(52)

(52)

To search for higher harmonics

associated with the zeros

associated with the zeros

in

in

, we compare the spectrum of

, we compare the spectrum of

by taking a Fast Fourier Transform with respect to

by taking a Fast Fourier Transform with respect to ,

,

(53)

(53)

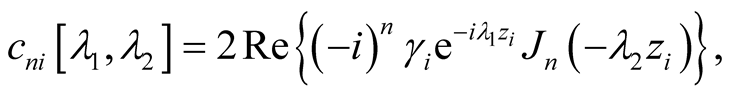

and compare the results with an analytic expression for the Fourier coefficients

of the

,

,

(54)

(54)

where

denotes the Bessel function of the first of order

denotes the Bessel function of the first of order .

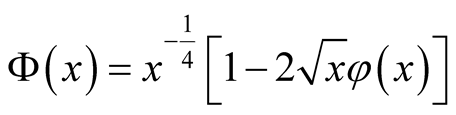

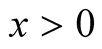

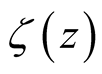

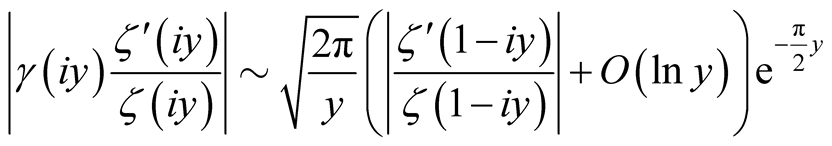

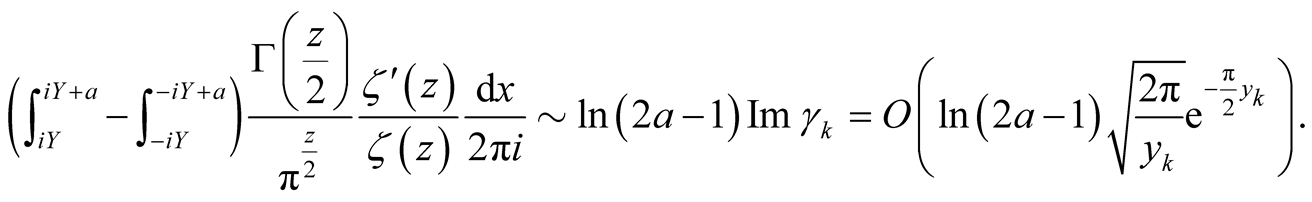

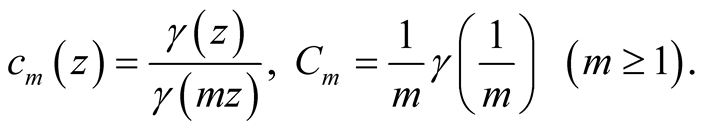

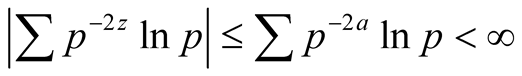

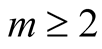

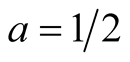

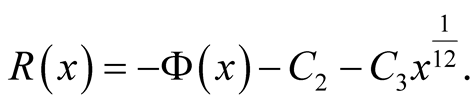

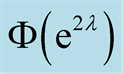

Figure 3 shows the first 21 harmonics in our evaluation of

.

Figure 3 shows the first 21 harmonics in our evaluation of , which is about

the maximum that can be calculated by direct summation in quad precision.

, which is about

the maximum that can be calculated by direct summation in quad precision.

7.Conclusions

The zeros

of the Riemann-zeta function are endpoints of continuation, defined by an expressed

by a regularized sum

of the Riemann-zeta function are endpoints of continuation, defined by an expressed

by a regularized sum

over the prime numbers defined by (6).

over the prime numbers defined by (6).

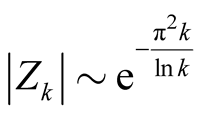

The zeros

of

of

introduce asymptotic harmonic behavior in

introduce asymptotic harmonic behavior in

as a function of

as a function of defined by the sum

defined by the sum

of residues of the

of residues of the , shown in

Figure 2,Figure 3. Primes up to 4 billion

are needed to identify the first 4 harmonics, up to 70 billion for the 10 and up

to 1 trillion for the first 21. It appears that, effectively, the prime number range

scales exponentially with the number of harmonics it contains.

, shown in

Figure 2,Figure 3. Primes up to 4 billion

are needed to identify the first 4 harmonics, up to 70 billion for the 10 and up

to 1 trillion for the first 21. It appears that, effectively, the prime number range

scales exponentially with the number of harmonics it contains.

Theorem 1.1 describes a correlation between the distribution of the primes and the

distribution of the nontrivial zeros . Suppose there are a finite

number of zeros

. Suppose there are a finite

number of zeros

in

in . We may then consider

. We may then consider

for which

for which

gives rise to dominant exponential growth in

gives rise to dominant exponential growth in

in the limit as

in the limit as

becomes large. This observation leads to Corollary 1.2.

becomes large. This observation leads to Corollary 1.2.

can remain bounded in

can remain bounded in

only if the Riemann hypothesis is true, or if

only if the Riemann hypothesis is true, or if remains fortuitously bounded as an infinite sum over

remains fortuitously bounded as an infinite sum over

with no maximum in

with no maximum in .

.

Conversely,Riemann hypothesis implies

(55)

(55)

According to (9) and our numerical calculation shown in

Figure 3,the zeros

explored to large k by

explored to large k by

Figure 3.Shown are the absolute values of the Fourier coefficients

of

of

obtained by a Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) of (52) on the computational domain (53),

where

obtained by a Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) of (52) on the computational domain (53),

where ,

, covers 32 periods of

covers 32 periods of

(dots), on the basis of the 37,607,912,2019 primes up to 1,000,000,000,0039. The

resulting spectrum is compared with the exact spectra

(dots), on the basis of the 37,607,912,2019 primes up to 1,000,000,000,0039. The

resulting spectrum is compared with the exact spectra

of the

of the

given by the analytic expression (54) for

given by the analytic expression (54) for

(continuous line). Shown are also the individual spectra of

(continuous line). Shown are also the individual spectra of

for

for

and 15 associated with the zeros

and 15 associated with the zeros ,

, and

and . The match between the computed and exact spectra accurately

identifies the first 21 harmonics of

. The match between the computed and exact spectra accurately

identifies the first 21 harmonics of

in

in

out of 22 shown, corresponding to the first 21 nontrivial zeros

out of 22 shown, corresponding to the first 21 nontrivial zeros

of

of .

.

existing numerical experiments effectively probe (and constrain) a distribution in primes which extends exponentially large in k.

Acknowledgements

The author gratefully acknowledges stimulating discussions with Fabian Ziltener and Anton F.P. van Putten. Some of the manuscript was prepared at the Korea Institute for Advanced Study, Dongdaemun-Gu, Seoul. This research was supported in part by the National Science Foundation through TeraGrid resources provided by Purdue University under grant number TG-DMS100033. We specifically acknowledge the assistance of VickiHalberstadt,RichRaymond and KimberlyDillman. The computations have been carried out using Lahey Fortran 95.

References

- Keller, H.B. (1987) Numerical Methods in Bifurcation Problems. Springer Verlag/Tata Institute for Fundamental Research, Berlin.

- Hadamard, J. (1893) Etude sur les propriétés des fonctions entiéres et en particulier d’une fonction. Journal de Mathématiques Pures et Appliquées, 9, 171-216.

- von Mangoldt, H. (1985) Zu Riemann’s Abhandlung “Über die Anzahl der Priemzahlen unter einer gegebenen Grösse”. Journal für die Reine und Angewandte Mathematik, 114, 255-305.

- Titchmarsh, E.C. (1986) The Theory of the Riemann Zeta-Function. 2nd Edition, Oxford.

- Lehmer, D.H. (1988) The Sum of Like Powers of the Zeros of the Riemann Zeta Function. Mathematics of Computation, 50, 265-273. http://dx.doi.org/10.1090/S0025-5718-1988-0917834-X

- Dusart, P. (1999) Inégalités explicites pour Ψ(X), θ(X), π(X) et les nombres premiers. Comptes Rendus Mathematiques (Mathematical Reports) des l’Academie des Sciences, 21, 53-59.

- Keiper, J.B. (1992) Power Series Expansions of Riemann’s ζ Function. Mathematics of Computation, 58, 765-773.

- Ford, K. (2002) Zero-Free Regions for the Riemann Zeta Function. Number Theory for the Millenium, 2, 25-26.

- Borwein, P., Choi, S., Rooney, B. and Weirathmueller, A. (2006) The Riemann Hypothesis. Springer Verlag, Berlin.

- Littlewood, J.E. (1922) Researches in the Theory of the Riemann ζ-Function. Proceedings of the London Mathematical Society, Series 2, 20, 22-27.

- Littlewood, J.E. (1926) On the Riemann Zeta-Function. Proceedings of the London Mathematical Society, Series 2, 24, 175-201. http://dx.doi.org/10.1112/plms/s2-24.1.175

- Littlewood, J.E. (1928) Mathematical Notes (5): On the Function 1/ζ(1+ti). Proceedings of the London Mathematical Society, Series 2, 27, 349-357. http://dx.doi.org/10.1112/plms/s2-27.1.349

- Wintner, A. (1941) On the Asymptotic Behavior of the Riemann Zeta-Function on the Line . American Journal of Mathematics, 63, 575-580. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2371370

- Richert, H.E. (1967) Zur Abschätzung der Riemannschen Zetafunktion in der Nähe der Vertikalen σ = 1. Mathematische Annalen, 169, 97-101. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF01399533

- Cheng, Y. (1999) An Explicit Upper Bound for the Riemann Zeta Function near the Line σ = 1. Rocky Mountain Journal of Mathematics, 29, 115-140. http://dx.doi.org/10.1216/rmjm/1181071682

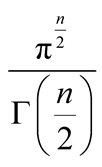

NOTES

1When

is an integer,

is an integer, is one-half the surface area of

is one-half the surface area of .

.

. Also

. Also