Creative Education

Vol.08 No.12(2017), Article ID:79452,23 pages

10.4236/ce.2017.812134

The Use of Cell Phones in School: Hybridization of Knowledge and Teaching Practices

Josiane da Cruz Lima Ribeiro1, Rodrigo dos Reis Nunes2, Ricardo José Rocha Amorim2

1State High School João Queiróz, Department of Education of the State of Bahia, Tapiramutá, Bahia, Brazil

2Department of Education, University of the State of Bahia, Campus IV, Jacobina, Brazil

Email josianeribeiro@gmail.com, rodrigoserrolandia@hotmail.com, amorim.ricardo@gmail.com

Copyright © 2017 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY 4.0).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received: August 21, 2017; Accepted: September 26, 2017; Published: September 29, 2017

ABSTRACT

This work has investigated how the experiences with the use of the cell phone in the school can imply innovations in teaching and learning aiming to know if, through a teaching plan, we could produce an interdisciplinary project contemplating the use of the cell phone in the classroom. Initially, we outlined a panorama of the school in the digital age, exposing obstacles and possibilities of change from the insertion of mobile technologies in the school space. We know about the relevance in approaching the use of the cell phone as a mobile technology in education, since it has been a necessary item for the consumer society, which reflects the identity of its users and enters the classrooms attached to the student’s bodies. Most of teachers are unprepared to deal with these demands that emerge from the digital age, needing to reflect and act on their practice to meet the aspirations of digital natives and contemporaneity. We undertook a qualitative research and adopted with predominant research-action, during the process, considering the specificities of the school context. The results obtained from experience, based on a dialogic, reflexive and participatory relationship, enabled teachers to reflect and act on their pedagogical practice and culminated in a Good Practices Guide. The guide was prepared in collaboration with the teachers who participated in training workshops. It contains the rules for the use of the cell phone in the school with recommendations on the use of classroom applications, didactic sequences and interdisciplinary projects. With the outcome of the research and training undertaken, the viability of using the cell phone in the school materialized through the productions and interventions of the teachers and the achievement of the proposed objectives allowed the understanding that teaching and learning can be hybrids and occur on network, anywhere, anytime.

Keywords:

Cell Phone, Hybrid and Ubiquitous Learning, Digital Native and Immigrant

1. Introduction

Immigrants and digital natives are immersed in the world surrounded by technologies, mobile culture, cyber culture, establishing a cohesion between social life, cell phones and the internet.

If technology is society itself, as Castells (2009) tells us, we cannot frustrate by realizing that “in contemporary cities, traditional spaces of place (streets, squares, avenues, monuments) are, little by little, becoming spaces of flows, flexible spaces, communicational, digital places” (Leão, 2004: 21) and the school is limited in this space and the incursion of digital mobile technologies to provide significant learning.

According to Leão (2004) , we must incorporate the triple vision and realize that cyberspace encompasses computer networks, interconnected people and the space (virtual, social, informational, cultural and community) that emerge from the human-document-machines. Moreover, we need to consider that there is no cultural multiplicity and identity only in cyberspace, and these are built in the daily doing, in subjective contacts.

Youth born in the digital age, the digital natives, intensively experience interactions between machines, such as cybernetics being, provided mainly by immersion in mobile technologies and the internet of things, establishing qualitative ways of learning, educating, interacting and living.

For Fundação (Telefônica, 2014) , which carried out the JuventudeConectada research, conceived by the Foundation, in partnership with IBOPE Inteligência, the Paulo Montenegro Institute and the School of the Future―USP:

“We cannot depreciate the impact that these innovations should have on today’s way of life, increasing the degree of discomfort of digital immigrants in the face of the need to learn to relate to “smart devices” that until recently were simply a refrigerator, a TV, or a clock, and did not require large processes to be operated. On the other hand, for digital natives and, therefore, the focus of this research, these devices will be a natural extension of the controls they already play in games, smart TVs, smartphones and tablets. The admirable new world has never been so new or challenging.” (Telefônica, 2014: 16) .

This research aims to understand opportunities, transformations and trends of young behavior in the digital age, from four research axes: education, activism, entrepreneurship and behavior and brings contributions on the theme developed here. Among the data, we highlight those referring to young people from the northeast of Brazil who stand out as the biggest enthusiasts of Internet use, for 60% of young people surveyed, the internet changed their information search habits, for 67%, the internet contributes to approximate people. Privacy and data security is a cause of concern for 63% of the young people heard (Telefônica, 2014: 111) .

The school needs to adapt to the social practices that emerge from this “networked society” (Castells, 2009; Papadakis, 2016) , because every day teachers and curricular knowledge lose space in dispute with cyberspace and cyberculture (Lemos, 2009; Lemos, 2013) .

The simple distribution of devices in schools is one of the factors that intensify this distance, since this insertion does not attempt to positively integrate the contemporary technologies in the curriculum, considering that the teachers do not participate in processes of formation that make them appropriate of these technologies.

In this sense, Perrenoud (2002) conceives reflexive practice and critical involvement as priority orientations for teacher training, defending the idea that social transformations and innovations are perceived in school very slowly, mainly because the will to change the school and adapt it to mutant social contexts is not shared by all, in view of the precariousness of teaching work, low wages, “doing better with less” slogans, among other factors. In addition to teaching content, the teacher needs to possess/construct other knowledge that is given by the exchanges between colleagues, by their experience and by the continuous teaching practice. Thus Perrenoud (2002) states that the “reflexive paradigm” can articulate knowledge, practice, experiences, efficacy and ethics and favor learning through action-reflection-action.

The acquisition of knowledge and the practice of innovation by teachers is a complex and nonlinear process. Imbernón (2011) tells us that this complexity is overcome when the training adapts to the educational reality of the learner, making it meaningful and useful when the training has a high adaptability component to the different reality of the teacher. The reflexive stance defended by Perrenoud (2002) , based on the ideas of Donald Schön, is nourished by the will of the teacher to carry out his/her work, by overcoming limits, by reflection on his/her action with knowledge, with people, institutions, technologies. For the author, inserting such a position in the professional identity of the teacher:

“[]…is to free professionals from prescribed work, to invite them to build their own procedures according to the students, the practice, the environment, the possible partnerships and cooperation, the resources and limits of each institution, obstacles found or foreseeable.” (Perrenoud, 2002: 198) .

In the 21st century, the role of the reflective teacher demands the incorporation of pedagogical mediation, where the teacher is the facilitator, or motivator of learning, who is available to be a bridge between the learner and his/her learning, teachers and students to collaborate to reach their goals (Masetto, 2013; Papadakis, 2016) .

Thus, including the technologies in the school with access to the internet does not guarantee learning by the teachers to the students, the pedagogical practices are not modified and the school has not been able to be a producer of knowledge and culture. Also, it is added to the fact that teacher training in technologies is incipient and fragile because it focuses on “punctual, lightening and compensatory actions” (Richit, 2014: 87) .

In the face of the considerations between the culture of the digital natives and the complexity surrounding the pedagogical practice, we see that “the school is in crisis because it is incompatible with the subjectivities of contemporaneity” (Sales, 2014: 242) , at the same time that there is still an anachronistic curriculum, unable to respond to the demands and temporalities that are currently configured.

In this way, for Barbosa et al. (2011) and Papadakis (2016) , education must stop focusing on the teacher and focus on the subject’s action, rethinking the structure and organization of curricula―which are still linear and fragmented―and suggest the m-learning (mobile learning) and u-learning (ubiquitous learning) as forms of learning that involve the profile of digital natives.

Initially, the concept of mobile learning was conceived as an extension of e-learning, but mobile learning (m-learning) “refers to learning processes supported by the use of use of mobile and wireless information and communication technologies, whose key feature is the mobility of learners (Papadakis & Kalogiannakis, 2017) .

Mobility is what stands out in mobile learning because it proposes other educational spaces and times. Thus, there are mobilities of physical order (displacements, different spaces), technological (different devices accompany their users, the cell phone, for example), conceptual (learning of different concepts and contents), socio-interactionist (we learn with interactions with diverse groups) and temporal (we learn all the time) (Barbosa et al., 2011; Papadakis & Kalogiannakis, 2017) .

The ubiquitous term came from Mark Weiser’s (1991) conception of ubiquitous computing, which is the idea of several computers or computing resources, such as cell phones, cars, video games, among others, being accessed by a single individual, which is understood as the third wave of computation, preceded by the first wave (several people/a single computer), second wave (one person/one computer). Ubiquity is present and has become naturalized in our daily lives in the most different “intelligent” computational devices. In this way, the concept of u-learning:

“refers to learning processes supported by various mobile and wireless information and communication technologies, sensors and localization mechanisms, which collaborate to integrate learning into their learning context and their surroundings, allowing the formation of virtual and real networks between people, objects, situations, and events, so that it can be supported a continuous, significant and contextualized learning to the learner.” (Barbosa et al., 2011: 28) .

In this perspective, the ubiquitous learning (u-learning) encompasses the learning situations supported by accessible information and communication technologies, not limited to them, since in addition to carrying technological devices, the learner has access to several other objects in his/her computers that can be used for a variety of purposes.

Saccol, Schlemmer and Barbosa (2011) develop these learning concepts and establish a study showing benefits, limitations and advances for the use of mobile devices, since certain practices can only be restricted to a purely technological approach and simple reproduction of concepts and techniques.

Considering the various benefits and limitations of mobile and ubiquitous learning, we have noticed that mobile technology favors relevant changes in teaching and learning, reducing the distance between who teaches and learns, provoking a review of the roles and functions performed by the subjects of learning.

It is not a matter of proposing a theory of learning, but of promoting a pedagogical adaptation of existing ones, which will result in a hybrid learning, mixing the already existing forms of pedagogical doing with emerging forms. It is important to emphasize that the emphasis on technologies will not cause changes in education, “but the way the subjects use it is that ‘emerges’ and ‘shapes’ the innovation” (Barbosa et al., 2011: 99) .

The complexity that permeates the educational process is evident, especially in the digital age, virtualized, of networked society, of information, of increasingly globalized and plural knowledge. Schools still cannot keep up with the rapid changes of the contemporary world, become less and less attractive and are unable to integrate other forms of learning, since they sometimes deny the incorporation of technologies in pedagogical action because they have not yet understood their potentialities.

Many opportunities are lost, the first is to contemplate the knowledge and cultures of the plural subjects who enter the school spaces, with all their diversity of identity and multiplicity of languages. The second is deterritorialization and reflection of their practices, by allowing themselves to explore and include the potentialities of cultural artifacts that emerge from cyber culture and are in the hands of learners, natives, and digital immigrants. The third, maybe the most important, is to open up to learn to learn, where teachers, managers and parents in a dialectical relationship with their students and children, metamorphose themselves to act in the world that more and more, transcends the limits of cyberspace.

According to Kenski (2013) , “flexibility, mobility, personalization of paths, attendance to individual needs are just some general aspects of the new educational demands, more coherent with the multiple temporalities” (Kenski, 2013: 15) .

The school of the digital age needs to reorganize itself to make sense in the life of teachers and students and it must become a learning school (Bonilla, 2002) that contemplates the insertion of digital technologies in a critical and dialectical way, making choices that support the education and learning needs.

Therefore, considering digital technologies as a new way of teaching and learning to meet the expectations of postmodern subjects requires a connection between public policies, network learning, continuing education (Perrenoud, 2002) and permanent (Imbernón, 2011) of teachers in service and pedagogical mediation (Masetto, 2013) so that the spaces and times of learning are extended and become spaces of flows, transforming (in)formation in knowledge.

In the next topic, we will deal with the workshops, since in order to achieve teacher education we need to promote reflection-action-reflection cycles and produce a network of dialogues between teachers and students about the inclusion of the cell phone in the classroom as a tool of learning. With the experiences of teacher practices, working with workshops as a research device, we were able to construct interdisciplinary projects that contemplated the use of the cell phone in the classroom.

2. Teaching Practice: Workshops as a Device

Articulating action and reflection in the educational context is a challenge that must be established as a recurrent practice in making educational, especially when we use workshops as a device in teaching practice. We adopted the workshops as a methodology, since they presuppose collective formation, interaction, participation, exchange of knowledge, creativity, dialogue in favor of the collective and dialectical construction of pedagogical knowledge that joins theory and practice, in an adaptive coming and going for the needs of teaching and learning.

When we bring the workshops as a device, we think of the workshop design as a method for building strategies and knowledge, which favors theory and practice for the achievement of common goals, in our case the use of the mobile phone as a learning tool. We thought of moments that offered opportunities for experimentation of concrete learning situations, the deepening of theoretical knowledge, the collective, individual and in pairs production of didactic sequences and interdisciplinary projects that contemplate the use of the cell phone in the classroom in educational and critical way.

The workshops were done in four moments, based on a previous flexible planning that included aspects of the discussions and studies of the initial meetings of the practice and also of what was signaled by the teachers in the process of partial evaluation of the meetings.

The researcher, also as a teacher, was not limited to the role of reproducing knowledge, but rather she mediated the workshops, allowing the collaborating teachers to share/deepen the knowledge and discoveries, in a supportive, interactive, collaborative, exchange and appreciation environment of the lived experiences.

As a first objective, we planned to build through the workshops opportunities for developing pedagogical work, including the use of the cell phone in the classroom, integrating the teachers’ prior knowledge, acquiring new knowledge and critical reflection on their practice. Throughout the meetings, the workshops developed involved the knowledge of theories, the elaboration of interdisciplinary activities from real contexts of teaching and learning, analysis and reflection of sequences, projects and a final product.

We articulated the demands that emerged from research devices and meetings with teachers in four moments that are complementary to each other:

Workshop 1: The world in the palm of the hand-Reading circle on mobile, ubiquitous learning and hybrid teaching and lesson plan production using mobile applications;

Workshop 2: First touches-Elaboration of proposals/didactic sequences contemplating the topics: Nomophobia, Netiquette, Internet Ethics, Internet Search, Nudes, Applications, Sustainability and Use of Mobile, Virtual Identity; Partial evaluation of the intervention;

Workshop 3: Sharing and experiencing knowledge-Participation of the digital native Antonio Vinicius Machado de Almeida to hold workshop on the Prezi with teachers; Socialization of experiences on the use of video editors KineMaster, VivaVídeo and Google docs for the elaboration of online questionnaires;

Workshop 4: Final touches-Elaboration of an Interdisciplinary Project; Preparation of the Good Practice Guide-Use of the cell phone in the school and final evaluation of the intervention.

This last workshop aimed to build an interdisciplinary project, including one of the subjects suggested by teachers and students during the workshops and studies carried out to prepare the Guide to Good Practices-Use of mobile phones at school.

We started the discussion about the subject that would generate the proposals of the Guide based on what we discussed during the practice and what it presented as a demand in the classroom. The teachers opted for Mobile Citizenship so that we could include in the proposals the ethical question of cell phone use, sustainability, among other aspects. Continuing the discussion, each step described in the script includes a commentary or guidelines. The material was delivered printed and we also posted on the Facebook group so that all the teachers had access and could consult it when they considered it necessary. We discussed each point and added the information and suggestions of the group of teachers. Finally, we made the orientation of the proposal, requesting that the teachers consider the subject generating of the proposal, as well as all the discussions and activities carried out during the study on the use of the cell phone in the classroom, also considering contents of his/her area or the topics discussed.

The proposals should consider activities that favor the use of the cell phone both in school space and in other spaces and contemplate the suggestions of use discussed or tried in the practice.

In the space of the meeting, the groups were formed and began to outline their ideas, discussing, researching in their notebooks, cell phones, tablets and computers in the teachers’ room. We helped the groups, asking questions, suggesting sites, among other aspects.

Teachers have prepared the following proposals:

@ Social Networks at School: ethical and moral, a pedagogical goal;

@ Ethics: living in the digital world;

@ Hybrid reading on Facebook;

@ The functionality of the applications;

@ Use of the cell phone as a learning tool.

The proposals did not directly address the issue of Mobile Citizenship, but rather a diversity of approaches that considered the aspects signaled by students and teachers during activities, studies and workshops. In addition, in our opinion, they considered the availability of teachers to work with the subjects and uses of the cell phone that they demonstrate to have more skill and safety.

3. Reflections and Ponderations

In this section, some reflections are presented about the productions made in the workshops (didactic sequences and interdisciplinary projects) with an analysis of the strategies used by the teachers according the cell phone modality of use in the classroom. Also, the final products thought by them in the elaborated proposals to realize as the provided practice implied innovations in teaching and learning.

By planning this practice proposal, we started with the idea of providing to teachers some moment so that they could reflect and intervene on/in pedagogical practice, taking into account the demands that emerged from the student’s entrance into the school, carrying their cellular devices. Cellular devices have a wide diffusion among the most popular classes, according to our Brazilian reality―especially in Bahia state and in Tapiramutá city. This technology, “in the hands of the student”, allows to innovate the methodologies used and transform the traditional routines into more dynamic activities that bring the student to the center of the learning process in a curious and creative way.

By proposing to teachers the elaboration of didactic sequences contemplating the subjects chosen and suggested by them and by the students, we aimed to understand if, when conducting a workshop with these subjects, teachers could review their (pre)conception, learning with others and positively including mobile technologies in “agenda” of the pedagogical routine.

The methodologies/strategies used in the sequences produced by the groups of teachers show an openness and flexibility by firstly considering “the voice of the student”, since the beginning of the activities always started from the previous knowledge of the students, of a chat, of discussions about the subject and the diagnosis of the problem emphasized in the sequence. We consider this as a gain for planning because it gives students greater participation, involvement in activities and demonstration of the skills and knowledge they already have about the technologies and can share with their classmates and teachers as well. This methodology, according to Barbosa et al. (2011) , is problematizing problem-based learning, which awakens the curiosity and interest of learners to identify “temporary doubts or provisional certainties about the problem to be investigated” (Barbosa et al., 2011: 67) . It also highlights some benefits regarding the adoption of this methodology combined with the use of technologies:

• It values the daily knowledge of the subject that emerge from its context (the starting point);

• It instigates curiosity, promoting research, manipulation, discovery, exploration, experimentation and creation;

• It values learning to think, learning to ask questions, learning to learn, learning to be and learning to live together;

• It enables a high level of interaction and interactivity, as well as the articulation of different points of view;

• It enables the paradigm to be broken, shifting the teacher from the role of principal actor and placing him as a partner in the process. (...) (Barbosa, et al., 2011: 68) .

To illustrate the excerpt, let’s take as an example part of the sequence about Cell Phone and Sustainability:

We observed that the initial moment of the sequence reaffirms the benefits of the problematizing methodology, widens the possibilities of interaction between the teacher and the students, prompts the research that will be oriented later to this stage, the critical reflection on the environmental impacts caused by the inappropriate disposal of the cell phone in the environment, among other things.

The second moment of the sequence was described as follows:

In this sequence, the teachers started from the students’ prior knowledge and went on to guide the research on the Internet, directing them to seek the complementary information for the questions that were asked and to know other aspects relevant to the subject in question. The lectures do not appear as the main element, the teachers act as learning provokers, articulators of the practice (Barbosa, et al., 2011) , accompanying the students in the search process of the construction of knowledge until the achievement of the proposed objectives and the concretization of learning in the socialization of the final product.

In addition to using the cell phone to be a research tool, the sequence will provoke a critical reflection on the environmental impacts caused by excessive consumption of cell phones to “meet” the fads and launches that overlap daily. Thus, through this planning, we understand that the teachers were able to convert the studies carried out in the training meetings and to allocate the pedagogical use of the cell phone to the research in the classroom.

The other strategies used by the teachers for the elaboration of sequences and projects were:

We organized the strategies used in strategies without using technological devices, hybrid and using technological devices in order to perceive the proposed diversity and also how many didactic strategies have been based on technological resources, as cell phones, tablets as video projector, notebooks.

As we can observe in Table 1, hybrid strategies and the use of technological devices dominate teachers’ preference for planning, mainly because they are elaborated proposals aimed at including the use of the cell phone in the classroom. Strategies that do not use technological devices are no less provocative of learning, since they provide an initial contact with the subject, from many ideas to more comprehensive and collective actions such as the elaboration of a plan of action of conscious consumption with members of the Collegiate and the Environmental Department of Tapiramutá.

So, we believe that it is necessary to emphasize that when we spread the idea of using the cell phone in the classroom, we look forward to a hybrid education based on blended methodologies that provide mobility and connectivity to learning. For Moran (2015) , that defends hybrid education as a key concept in today’s education, “hybrid is a rich, appropriate and complicated concept. Everything can be mixed, combined, and we can, with the same ingredients, prepare various ‘dishes’ with very different flavors.” (Moran, 2015: 27) .

The author emphasizes the “complicated” term, possibly because managers and teachers do not always make the right decisions when adopting or not technologies for use, because they have difficulties to evolve, to be coherent and not to practice what they teach, generating an incoherence of behaviors. We can establish a link with the results of the questionnaires in the mosaic of technological habits where 30% of teachers stated that they allow students to use the cell phone in the classroom, while 95% of teachers reported that they bring the cell phones to school and 85% keep them connected/available daily. While CEJQ’s managers and teachers remain connected and immersed in the network, they wanted the use of cell phones banned in classrooms.

It’s very interesting to observe a process of reflection and intervention on the practice for teachers to rethink the role of mobile technologies in the school space and to provide the hybridization and cyborgization of the curriculum to meet the needs of the high school youth, as we saw in the Table 1. Still, in the words of Moran (2015) :

“Teaching is hybrid because we are all learners and educators, consumers and producers of information and knowledge. In a short time, we have passed from large media consumers to “prosumers”-producers and consumers of multiple media, platforms and formats to access information, publish our stories, feelings, reflections and worldview. We are what we write, what we post, what we “liked”. (...) We all teach and learn all the time, in a much freer way, in more or less informal, open or monitored groups.” (Moran, 2015: 28) .

There were multiple and rich strategies designed by teachers to use applications, social network, produce diverse media, read hypermedia texts, among others, to give priority to students’ “prosumer” involvement, with more attractive methodologies and teaching by interdisciplinary projects. We believe that teachers have been able to include in their planning uses of the cell phone they have already mastered and have contemplated others that have been provided in the practice and research spaces.

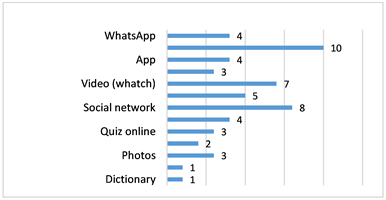

Among the other aspects of sequences and interdisciplinary projects, we want to consider the modalities of cell phone use that were made feasible in the teachers’ proposals. We checked the usage recurrences and arrived at the following result (Graphic 1):

The highest incidences of cell phone use were with research and social networking, (seven recurrences for Facebook and one for Pral-portal of educational relationship between students and teachers), which coincides with the greater

Table 1. Strategies-Sequences and projects.

Source: Research Data.

uses signaled by teachers and students.

We understand by means of the modalities of use of the cellular adopted by the teachers in the sequences and projects that, after the studies and the realized workshops, they managed to include pedagogically the cellular in the planning of the activities, contemplating what was discussed in the workshops, which implies innovations and hybridizations in teaching and learning, mixing online activities with activities based on the analog format of teaching.

Graphic 1. Modalities of cell phone use.

Valente (2015) tells us that, in pedagogical approaches that contemplate hybrid teaching “strategy consists of focusing on the learning process on the student rather than on the transmission of information that the teacher traditionally performs” (Valente, 2015: 13) . He also complemented by saying that the student studies and accesses different environments, participates in varied learning situations, solves problems, among other activities with the collaborative support of teachers and colleagues.

Even teachers who did not adopt specific models of Hybrid Teaching as presented by Bacich, Neto, & Trevisani (2015) ―model of rotation, flex model, a la carte and enriched virtual model, which was not the focus of this research, we noticed that the strategies and modalities of use offered by teachers take to actions that are in line with the methodology of hybrid teaching. We believe that with pedagogical improvement through lifelong learning, we could experience researches and interventions the hybrid teaching models for the enrichment of learning mediated by mobile technologies.

The last items of analysis that we will bring to this discussion will be the final products of the interdisciplinary projects and sequences, which are listed here in the order that appears in the guide to good practices:

• Production of videos (theatrical plays) on the ethical and moral issues of the use of the cellphone in the intra and extracurricular space;

• Production of essays and articles of opinion;

• Production of a Photographic Exhibition on the Uses of Contemporary Technologies: an issue of accessibility;

• Production of Interviews;

• Independent or group production―Workshop Technologies and use of cellular and social networks in the classroom;

• Magazines with tips for using social networks;

• videos and Theatrical plays;

• Groups in social networks;

• Facebook profile of the authors studied and their respective works;

• Biographical video of the author searched;

• Posters and information;

• Graphs, polls, slides and round tables;

• Internet Label Campaign (Netiquette) in the school space and in the local community;

• Elaboration of etiquette rules on the internet;

• Mental map;

• Audio recording (spot);

• Flyers and posters;

• Creation of a virtual school space in the school using PRAL to socialize the discussion;

• Video lesson on the subject studied;

• Online Mural of Application Usage Recommendation;

• First Seminar on Sexuality in School;

• Campaign for proper collection and disposal of cell phones;

• Videos, audios, photos, videos, posters published in social network;

• Video production “Sustainability”: what do we have to do with this?

• Conscious Consumption Action Plan;

• Newspaper;

• Production of the video with its respective edition: Interview with the midwives of our city;

• Photographic exhibition: The work of the midwives of Tapiramutá-Bahia;

• Production, editing and presentation of the video documentary IndiosPaiaiás at the 2015 Art Fair;

• Production of audios and videos with pronunciations in English.

The multiplicity and richness of products that teachers have been able to gather in interdisciplinary projects are clear. The final products sought in the projects are quite innovative, offer mobile and ubiquitous learning, articulate the school with other segments of society; using heterogeneous media, the productions of the students are inserted in the network, leading the teaching and learning.

Let’s take as example two final products that were planned and executed during the intervention and materialized in 2015: The photographic exhibition “The office of the midwives of Tapiramutá-Bahia” and the video documentary “ÍndiosPaiaiá”, both works were results of the classes of the History, on second grade, high school, in 2015. We followed the process of developing the didactic sequence in the classroom with the teacher and the students, observing the strategies that the teacher used so that the students learned, could carry out the steps and the activities. The productions were socialized by the classes on the XII Art Fair 2015, whose theme was “Tapiramutá: weaving memories, identities and cultures”, an event that has been happening in the school space for 12 years and every year it approaches a different theme.

The photographic exhibition was held in a stand entitled “Memories”, space in which were distributed several objects that are part of the culture of the city. With the field surveys carried out on the midwives in Tapiramutá, the students created a panel with the images, using sieves as ornament; they also produced an album contemplating the life histories of some midwives and a video with interviews that was being displayed in the “multimedia tv” in the stand for the visitors. The video was socialized in Jornada Pedagógica/2016 by the responsible teacher as one of the successful experiences of the year 2015.

About the documentary “ÍndiosPaiaiás”, the students defined it as “a short movie that assimilates the culture and history of the Paiaiás Indians with the city of Tapiramutá”. The movie was first shown in the classroom, at which time we were invited to watch the production of the students and reexhibited on one of the nights of the Art Fair on stage, in the outer area of the school for the school and local community, at that time, there were the presences of the mayor of the municipality and government secretaries who honored the production of the Students. The video can be watched at the link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YnR4IaK8LyU, with name “ÍndiosPaiaiás”, was published on December 29, 2015 and is a beautiful, original production that was created, recorded and edited only by the students.

The two final products highlighted bring us the understanding that by blending online and offline activities we can achieve excellent results that give the teaching and learning process meaning, dynamism, authorship, youth protagonism and motivation both students and of the teacher who obtain good Results in their proposals. According to Moran (2015) :

“Learning happens in the fluid, constant and intense movement between group and personal communication, between collaboration with motivated people and the dialogue of each one with himself, with all the instances that compose and define him, in a permanent reworking.” (Moran, 2015: 33) .

At the moment, we followed the teacher’s orientation with the classes to carry out these activities, we noticed that he always acted as mediator, there was no lecture moment, dialogue, collaboration, guidance for the use of technological resources and follow-up of the step-by-step activities of the groups were the distinctive traits for success to be achieved.

Thus, to reach these activities, the teacher had to provide adequate didactic treatment to the content, the proposed activities and see this as a differential for the promotion of learning, as traditional and mobile as ubiquitous learning. Only mechanically using mobile technologies by fad or by imposing others do not enable students to develop the skills and competencies needed to recognize themselves in the digital age.

We emphasize that difficulties arose from the materialization of planning in the sequences, so we instructed the teachers to review and detail their productions always thinking about a writing that would be divulged to others and that the sequences and projects would be available for appropriations and adjustments, which needed a look more careful. This difficulty lies in the mistaken practice of high school teachers in considering that only an itinerary of activities without detail is sufficient for good planning, as we have already observed in the absence of delivery of didactic sequences to pedagogical coordination and in discourses in complementary activities in the school unit.

In Good Practice Guide, not all interdisciplinary sequences and projects have the power to leverage such hybrid, mobile and ubiquitous learning as the two experiences cited, but we clarified that it was not our intention to conduct a hierarchy of productions, on the contrary, with all the discussions and practices provided, we are pleased to realize that teachers have innovated in their strategies, included different modalities of using the mobile phone and envisioned renewed final products to promote learning between the physical and digital worlds.

4. Architecting the Good Practice Guide “Cell Phone Use in School”

By attempting to elaborate the Good Practice Guide, we aimed to produce a guide that involves the steps of the actions and reflections that were implemented in the CEJQ, from the moment the class assembly was held, culminating in the elaboration of the combined ones for the use of the cell phone in the classroom until the production of the interdisciplinary projects, last stage of the intervention. In addition, we will bring in this chapter considerations regarding the final evaluation of the course to understand if the teachers think that the practice made possible the reflection on the challenges, perspectives and possibilities of pedagogical use of the cell phone in the school.

The feasibility of this final product is a way of giving visibility to what was built with study, research, reflection, action without being forced to prescribe how it should be used or handled, but rather to offer possibilities of using the cell phone in the classroom, in the expectation to innovate and intervene qualitatively in teaching and learning.

Good practices are taken by us as strategies, methodological possibilities for use of the cell phone in the classroom evaluated and built by teachers as innovative, productive and enriching pedagogical doing, so we qualify as “good practices” because we believe that the formation made the foundation of the production and supported the proposals made.

For the collective construction of the Good Practice Guide, teachers participated in a focus group, pedagogical discussion and workshops that provided diverse moments of learning, action and reflection on the practice and in the workshops were oriented to elaborate proposals of activities that contemplated the use of the cell phone in classroom. In the end, the Guide was organized on 86 pages, in which we covered most of the teachers’ productions in the sections, only digital productions (videos and prezis) were not included. It is structured as follows:

@ Section 1-Contains the cell phone classroom-based combinations that are the result of the Class Assembly, the first activity developed by the teachers in the school space, aiming at the dialogue with the students and the creation of rules to be assumed in the school space. In addition, there are suggestions for what activities the cell phone should be used, there is a text that deals with the impressions that natives and digital immigrants have regarding the cell phone and some guidelines that will guide the readers in the choice of applications to be used in the room of class;

@ Section 2-It is composed of didactic sequences with diverse subjects and that meet the suggestions of teachers and students. The teachers elaborated didactic sequences that contemplate diverse forms of use of the cell phone in the most different spaces (school, house, squares, streets of the city, among others). They are sequences that use the cell phone in its diverse potential to film, to photograph, to record audios, to make searches, to record notes, to follow the own learning, use of applications, among others;

@ Section 3-Contains the Interdisciplinary Projects: proposals elaborated collaboratively by the teachers, that contemplate the ethical use of the cell phone, of the social networks, the hybrid reading in the Facebook, the evaluation of applications, the analysis of virtual profiles and the accomplishment of survey with the community.

The didactic sequences and interdisciplinary projects complement one another, which give cohesion to the work that was done in the school space. Initially, we thought of developing only an interdisciplinary project that contemplated all the learning needs of the students, but with the immersion in the field we realized that the subjects that emerged were and are quite relevant to the proposal of the guide and we opted, together with the teachers, for not Transform into a unique project, but rather give variety to the focus and use of the cell phone in the classroom. This conferred on the collaborative production multiple hybrid teaching and learning opportunities merged between moments with analogical activities and moments with use of digital mobile technologies.

Thus, the development of the Good Practice Guide went beyond what we had envisaged as an objective, since we initially thought of a proposal and achieved a rich variety of interdisciplinary sequences, reflections and projects. Such multiplicity certifies to the cell phone other perspective than not as a “villain” or “distractor” in the classroom, but rather a cultural artifact, a pedagogical tool that can rather leverage other learning and consider the constant changes in the digital age.

As Kenski (2013) tells us:

“The pedagogical proposal appropriate to these new times must be no more than to retain information in itself. New referrals and new postures guide us to use filtering mechanisms, critical selection, collective reflection and dialogue about the focuses of our attention and the search for information.” (Kenski, 2013: 87) .

In the initial discussions about the problems caused by use of the cell phone in the classroom many teachers-not only in the space of the CEJQ, but through the media reports as they viralized videos in the network where a manager was attacked for “taking” the cell phone of a student, teachers prosecuted, among other situations―feared that the role of the teacher would disappear through the loss of authority in the classroom. In this view, with all the studies and reflections made, we realized that “school is the privileged space for the formation of people in citizens and for the contextualized systematization of knowledge” (Kenski, 2013: 86) .

In order for school and teachers to continue to make sense in the lives of students, whether they are natives, immigrants or digital colonizers, we need to constantly carry out a critical review of our pedagogical actions, given that the urgencies of this constantly changing world require qualified citizens to find themselves in this tangle of fragmented information and knowledge that become ephemeral swiftly.

The proposals presented in the Guide extrapolate this simple search for information, since they provide different moments of interaction among students, teachers, school community, local community and municipal agencies. This success has been achieved through the process of ongoing formation to which teachers have adhered, with the support of reflection on their practice, the acquisition of new knowledge, the valorization of their abilities, and the recognition of their limitations and the willingness to learn all the time.

The workshops were emphasized as a process that presuppose the reflection of the teachers about their practice, allowing them to “examine their implicit theories, their schemes of functioning, their attitudes, etc., carrying out a constant process of self-evaluation that guides their work” (Imbernón, 2011: 51) . In addition, this concept of practice subtends the discovery, organization, foundation, revision and construction of pedagogical knowledge individually and collectively (Imbernón, 2011) .

The exchange of experiences and the search for solutions to face the challenges that arise in schools must be the imperative for teachers to produce successful practices with the use of cell phones in the classroom. Good practices need to be disseminated so that the school community, the local community, other schools and the bodies to which we are subordinate be aware of the representations and connections of the use of the cell phone with teaching and learning.

In this way, taking advantage of the positive aspects of mobile technologies, we will be able to raise the quality of education through the activities proposed in the Good Practice Guide, creating environments conducive to personalization of teaching, fostering autonomy and cooperation between students and teachers. Through digital tools, users connect with hybrid learning processes, which can happen in the most diverse spaces, making them producers and knowledge sharers.

5. Final Considerations

At the end of the research and intervention process, we realized that the discussion about the banning of cell phones in the classroom became innocuous because of the massive use not only of the students, but also of the efforts of several institutions and researchers to contribute to thinking of digital mobile technology included in teaching pedagogical practices, as it has been done with other technologies that preceded this digital era.

We affirmed that non-mastery and non-comprehension of the pedagogical/methodological use of mobile digital technologies in the classroom are some of the factors that may have generated strangeness and discomfort for managers, teachers and, consequently, parents of students. This positioning is not intended to blame anyone, but rather to reinforce the need for ongoing formation as a premise for the provision of a quality education that is based on the incessant need of the school to attend to the society of which it is a part.

Such propositions lead us to conjecture that the school in the contemporary world needs deeper and more critical changes than the simple insertion of these apparatuses into its space. We believe that with the research and intervention undertaken in the CEJQ we can achieve the objectives we have set and respond satisfactorily to the research problems. As we could see in the description of the actions, the initial frisson caused by the entrance of the cell phones in the school was directed to the discovery of strategies for the appropriate and pedagogical use of TIMS.

Thus, the use of the cell phone in the classroom can become a useful tool for the teaching and learning process, it can re-signify the identities of teachers and students in the school space, since the uses we make of this mobile device is ubiquitous and engender new habits, practices, multiple interactions that do not fail to impact our identity constitution. The experiences with the use of the cellular in the school can imply innovations in the teaching and the learning in the perspective of hybrid learning and in network and through a plan of teacher formation we were able to produce interdisciplinary projects that contemplated use of the cellular in classroom.

The question of the use of the cell phone by the students was related to the control that the management and the teachers needed to have within the school unit, even if the teachers already used the cell phone to attend to their particular and professional needs, the same was not accepted for the students, being seen as transgression or disorder. With the early studies on the understanding of digital natives and their identities, because they no longer learn how teachers were educated or do not respond satisfactorily to the methodologies that are often used in school, teachers have come to recognize that student public needs other learning to motivate them and make them protagonists of teaching and learning.

Then, we realized that the training process undertaken in the CEJQ space was significant, contributing positively to the pedagogical practice of teachers. What can be corroborated when we ask them to highlight situations of their professional or personal life that have been modified from the discussions made, in this respect, we highlight the following comments/topics:

- Acceptance of the cell phone:

• The way of accepting the use of the cell phone in the classroom, which was once seen as something bad that only bothered, today was incorporated into pedagogical practices and is used as an ally of learning [sic].

• Personally, I learned that the mobile has not only entertainment functions but also applications that can promote learning. Professionally, using the cell phone as a learning tool for my students. Not ceasing to be sensitive to the group that does not yet have accessibility to its use [sic].

- Changes in habits and uses:

• After class assembly, I realized that my students were more concentrated in class and only used the cell phone when much needed [sic].

• The use I make of my cell phone today. I used it just to make calls. Today, I almost do not use the computer, because the cell phone serves a lot of my needs, mainly for research, banking applications and, especially, social networks. I’m almost a digital native [sic].

- Modifications and reflections on pedagogical practice:

• I did a Prezi and videos to present papers about my practice in the classroom. I was more curious to use the applications of my cell phone, such as the application of Banco do Brasil, Bradesco, the server portal, educational applications in my area [sic].

• Helped me to stop to think of learning situations in which I would continually seek to insert the digital technologies in my classes. Seeking in this way, create teaching and learning conditions for better use of the cell phone to interview, photograph, produce videos, research, applications for study [sic].

• Thinking that the teacher is not an absolute holder of knowledge, and that the student can also bring knowledge that collaborates with some moment of the lesson. Recognize students’ skills in areas I do not have, such as handling and knowledge of technologies. And that I can also put myself in the place of those who are learning [sic].

In addition to the highlighted topics, we also noticed that the identity of teachers, who have been placed on many occasions as “digital immigrants” or “digital illiterates”, has undergone subtle changes since they now perceive themselves as capable of learning with students and their students. Colleagues were divided and now are mingled between traditional and contemporary innovations that provoke uncomfortable changes, but on the other hand are propelling other forms of teaching and learning.

The changes related to the use of the cell phone in the classroom by teachers and students were also noticed, 95.5% of the teachers said they noticed changes in the way the students use the cell phone in the classroom, informed that the students “passed to be more aware of the appropriate use after the class assembly”, “began to use the cell phone for study, as research and not to stay in social networks”, “students have come to respect more the combined for the good use of the cell phone in the classroom”, “there was a motivation, interest on the part of learners with the activities suggested” and “ they came to see that the cell phone can be a powerful learning tool”.

Regarding the changes made by teachers, 100% reported that differentiated attitudes are visible and justified: “they began to modify their practices of use and are showing students that the cell phone is a great tool to promote learning”, “not there is more stress than ever asking students to keep their cell phone”; “When we qualify our educational practice, there are improvements in the learners’ learning”, “cell phone is now to be used yes!”.

The reports of the activities developed in the workshops and the mentioned passages, indicate the understanding that the habits and uses adopted by students and teachers in relation to the cell phone in the classroom experienced progressive qualifications, the cell phone is now seen as an ally as a beneficial tool which assists teaching and learning.

Given the complexity involved in the pedagogical work mediated by the digital technologies that reinvent themselves every day, they modify identities and demand other methodologies, learning, reflections and actions, we believe that the present study will have continuity and other implications in the other spaces and times that are offered in school spaces.

We concluded that the teacher practice needs are much more complex than the insertion of the cell phone as a pedagogical artifact in classroom, we say this because there are teachers who present difficulties of handling the technologies from the most basic use that is the formatting of works, elaboration of slides, sending of emails, use of social networks, video conversion, among other things, which is possibly an obstacle to the appropriation of technological innovations. It is only in qualitative researches involved, with direct interventions, that we can know and approach different educational realities on the same locus: there are teachers who are very skillful, they dominate diverse technological tools; on the other hand, there are others that lack basic learning in which concerns technological devices.

This leads us to say that the formations offered by the various educational sectors are based on very theoretical studies that often do not “arrive” in the practice of the classroom, in the day-by-day teaching. In addition, the speed with which the technologies are emerging is so massive and shocking that the school has not been able to closely monitor many of these technological changes. When teachers are able to take ownership of a new technology, this technology is already obsolete.

We believe that the research carried out is relevant to basic education, since it deals with themes that have not yet been supplanted in the digital age, brings to light reflections and propositions about the potentialities of cell phone use as a useful tool to the teaching and learning process, such potentialities imply educational innovations in the perspective of hybrid, mobile, ubiquitous and networked learning. The process of experiential formation supported these discussions, encompassing different forms of search for knowledge, understanding that the school has not taken account of the socio-cultural transformations that emanate from this era, which imposes the need for the permanent formation of teachers for the critical integration of new technologies on the teaching and learning process.

From the end of this work, we recognized that feedback of the pedagogical practice with alternatives for the adequate use of the cell phone in the school space in the motivation and construction of knowledge became feasible, supplanting the uncritical and vertical use of mobile technologies and bringing to the surface reflections on the subject and a rich understanding about the implications that the use brings for teachers and students, without ignoring that education is being constantly modified by social changings.

Acknowledgements

This work is partially supported by INES, grants CNPq/465614/2014-0 and FACEPE/APQ/0388-1.03/14.

Cite this paper

Ribeiro, J. C. L., Nunes, R. R., & Amorim, R. J. R. (2017). The Use of Cell Phones in School: Hybridization of Knowledge and Teaching Practices. Creative Education, 8, 1968-1990. https://doi.org/10.4236/ce.2017.812134

References

- 1. Bacich, L., Neto, A. T., & Trevisani, F. M. (2015). Ensino híbrido: personalizacao e tecnologia na educacao. [Hybrideducation: Personalization and Technology in Education.]. Porto Alegre: Penso. [Paper reference 1]

- 2. Barbosa, J., Schlemmer, E., & Saccol, A. (2011). M-learning e u-learning: Novas perspectiva da aprendizagem móvel e ubíqua. [M-Learning and U-Learning: New Perspective on Mobile and Ubiquitous Learning.] Sao Paulo: Pearson Prentice Hall. [Paper reference 8]

- 3. Bonilla, M. H. S. (2002). Escola aprendente: Desafios e possibilidades postos no contexto da sociedade do conhecimento. [Learning School: Challenges and Possibilities Put in Contextof the Knowledge Society.] Tese de Doutorado-Salvador: UFBA. [Paper reference 1]

- 4. Castells, M., Fernández-Ardévol, M., Qiu, J. L., & Sey, A. (2009). Comunicacao móvel e sociedade. Uma perspectiva Global. [Mobile and Society. A Global Perspective.] Lisboa: Fundacao Calouste Gulbenkian. [Paper reference 2]

- 5. Imbernón, F. (2011). Formacao docente e profissional: Formar-se para a mudanca e a incerteza. [Teacher and Professional Training: Forming for Change and Uncertainty.] Sao Paulo: Cortez. [Paper reference 4]

- 6. Kenski, V. M. (2013). Tecnologias e tempo docente. [Teaching Technologies and Time.] Sao Paulo: Papirus. [Paper reference 5]

- 7. Leao, L. (2004). Derivas: Cartografias do ciberespaco. [Drives: Cartographies of Cyberspace.] Sao Paulo: Annablume. [Paper reference 2]

- 8. Lemos, A. (2013). Cibercultura—Tecnologia e vida social na cultura contemporanea (6th ed.). [Cyberculture-Technology and Social Life in Contemporary Culture.] Porto Alegre: Sulina. [Paper reference 1]

- 9. Lemos, S. (2009). Nativos digitais x aprendizagens: Um desafio para a escola. [Digital Natives vs. Learning: A Challenge for the School.] Boletim Técnico do Senac, Rio de Janeiro, 35. [Paper reference 1]

- 10. Moran, J. (2015). Educacao híbrida: Um conceito-chave para a educacao, hoje. [A. do livro] Lilian Bacich, Adolfo Tanzi Neto e Fernando de Mello Trevisan. Ensino Híbrido: Personalizacao e tecnologia na educacao. [Hybrid Teaching: Personalization and Technology in Education.] Porto Alegre: Penso. [Paper reference 6]

- 11. Masetto, M. T. (2013). Behrens, Marilda Aparecida. Novas Tecnologias e mediacao pedagógica. [New Technologies and Pedagogical Mediation.] Campinas: Papirus. [Paper reference 2]

- 12. Papadakis, S. (2016). Creativity and Innovation in European Education. 10 Years Twinning. Past, Present and the Future. International Journal of Technology Enhanced Learning, 8, 279-296. [Paper reference 3]

- 13. Papadakis, S., & Kalogiannakis, M. (2017). Mobile Educational Applications for Children. What Educators and Parents Need to Know. International Journal of Mobile Learning and Organisation, 11, 256-277. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJMLO.2017.10003925 [Paper reference 2]

- 14. Perrenoud, P. (2002). A prática reflexiva no ofício de professor: Profissionalizacao e razao pedagógica. [Reflexive Practice in the Teacher’s Office: Professionalism and Reason Pedagogical.] Porto Alegre: Artmed. [Paper reference 5]

- 15. Richit, A. (2014). Formacao de professores em tecnologias digitais: Desdobramentos nas práticas escolares em face do Programa Um Computador por Aluno. [Teacher Training in Digital Technologies: Developments in Practices in the Face of the One Computer Per Student Program.] Colombia, 14. http://aprendeenlinea.udea.edu.co/revistas/index.php/unip/article/view/21342 [Paper reference 1]

- 16. Sales, S. R. (2014). Tecnologias digitais e juventude ciborgue: alguns desafios para o currículo do ensino médio. In: J. Dayrell, P. Carrano, & C. L. Maia (Eds.), Juventude e ensino médio sujeitos e currículos em diálogo (pp. 229-248). [Youth and High School Subjects and Curricula in Dialogue.]. Belo Horizonte: UFMG. [Paper reference 2]

- 17. Telefonica, J. C. (2014). Fundacao Telefonica. [Telefonica Foundation.] Sao Paulo: Fundacao Telefonica. http://fundacaotelefonica.org.br/acervo/juventude-conectada/ [Paper reference 3]

- 18. Valente, J. A. (2015). Prefácio. [A. do livro] Lilian BACICH, Adolfo Tanzi Neto e Fernando de Mello Trevisan. Ensino Híbrido: Personalizacao e tecnologia na educacao. [Hybrid Teaching: Personalization and Technology in Education.] Porto Alegre: Penso. [Paper reference 2]

- 19. Weiser, M. (1991). The Computer for the 21st Century. Scientific American. https://www.lri.fr/~mbl/Stanford/CS477/papers/Weiser-SciAm.pdf [Paper reference 1]