American Journal of Industrial and Business Management

Vol.3 No.2(2013), Article ID:30136,7 pages DOI:10.4236/ajibm.2013.32027

Technology Enabled Customer Relationship Management in Supermarket Industry in Nigeria

![]()

National Centre for Technology Management, Federal Ministry of Science and Technology, Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife, Nigeria.

Email: muyiwaolamade@yahoo.com, yusuffshola@yahoo.com, kz4tawa@gmail.com

Copyright © 2013 Olamade O. Owolabi et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Received February 1st, 2013; revised March 1st, 2013; accepted April 8th, 2013

Keywords: Technology; Customers; Relationship Management; Supermarket

ABSTRACT

Customer Relationship Management (CRM) is an enterprise-wide business strategy directed at attracting, retaining and effectively serving customers to grow up their value over the long term. Because customers differ in their preferences and purchasing habit, and their mobility is enhanced by increasing availability of information, firms invest in technologies that help them gain detailed understanding of their customers, allowing them to know how to respond to customer needs and market products and services more effectively. While the modern CRM strategy is intensive in the use of analytical technologies, the Nigeria supermarket industry still at the first stage of its development phase have largely interacted with customers through personal interaction partly due to the low level of competition for customers, high cost of investment in analytical CRM infrastructure and lack of dynamic capability to integrate technology, people and processes.

1. Introduction

In today’s hyper competitive business environment, the process of acquiring, serving, and retaining customers is crucial for business success. Customers are assets, and their values grow and decline [1]. The health of a firm is intricately linked to the health of its customer base. The ability, therefore, to acquire and grow customers’ assets over the long term is strongly correlated with the requirement of businesses to grow and prosper in the long term. Firms aiming to serve their customer better and forestall their deflecting to competitors due to dissatisfaction need superior strategies to support their business processes.

These processes are directly or indirectly associated with the services rendered by firms to get the best value from their customers. Implementing an enterprise-wide approach to customer management that coordinates tailored treatment of customers based on their value and needs, among other business improvement strategies, has been widely recognized as enhancing the value of customers. This can be achieved through a meticulously implemented Customer Relationship Management (CRM) program.

A large base of loyal customers is required for the survival of and long term prosperity of a supermarket. While the supermarket industry is still at the early development stage in most African countries aside from South Africa, supermarkets in more advanced economies have developed capability to attract, retain and grow the value of customers over the long term.

According to [2], African supermarket industry has witnessed a developmental growth since the mid 1990s through Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) due to urbanization and the rise of the middle class in some African countries like Kenya and South Africa. [3] observed that the supermarket development phase in developing countries which started in the 1980s in the larger and richer Latin-America countries is now being experienced in some parts of South Asia and West Africa. Supermarkets in Africa are extending into poor neighborhoods of large cities and towns resulting in a diffusion and extension of supermarkets away from being mere luxury top-end niches to being mass market merchandisers. [4] conceptualized this development as a changing system of demand for and supply of supermarket services. In Nigeria, a number of supermarket chains have emerged, recent years, at the top end of the market catering to a limited market of high and middle income consumers and expatriates in Nigeria. This pattern, however, is changing as supermarkets are taking up vantage locations in poor neighborhoods in large cities. Opportunities for growth in the Nigeria supermarket industry are enormous. Presently, less than 2% of total food sales are through supermarkets. A 2008 global retail report placed Nigeria 11 out of the top 15 global markets by opportunity.

The objective of this paper is to examine the Customer Relationship Management (CRM) practices of the supermarket industry in Nigeria with particular emphasis on the use of technology to retain and grow customer value. The paper sought first to know the prevalence of the application of technology enabled CRM in the supermarket industry, the type of technology deployed and intensity of use as well as the constraints to the deployment of technology in customer relationship management. Four cities (Lagos, Abuja, Port Harcourt and Kano) considered as being the commercial and industrial hubs of the country with considerable size of middle class population and expatriate workers were selected for the study. Response to the questionnaires was encouraging with retrieval rate of about 73%. Information was obtained through structured questionnaires administered on the senior management staff with over five year of experience in the marketing and ICT departments of the supermarkets. This was supplemented by oral interview with help desk officers and check-out counter staff.

2. Review of Literature

2.1. Concept of CRM

Customer Relationship Management (CRM) is the seamless integration of technology and marketing strategy to effectively manage and improve relationship with existing and potential customers to meet business objectives. It is a business approach that integrates people, process and technology to maximize relationships with customers [5,6]. The early application of CRM was offered as a solution to redefine customer relationship using computerized tools. Managing customer relationships was easier in earlier times as merchants have considerable knowledge of their customers; who they are, what they generally purchase, and could also predict what their future purchases could be. The knowledge helped the merchants then to create highly effective customer relationships [7,8]. As important and effective the traditional customer relationship strategy was, it could not stand up to the increasing challenges of today’s rapidly changing, information intensive business environment. Customers now are more mobile than before, city size is greatly expanding, and firms are adding more new units and getting larger. Generally, marketing reach is greatly expanding. The unpredictability of customer buying behavior especially in information-rich sectors like retail (supermarkets) is fast giving way to one-to-one marketing with the aim to personalizing the marketing efforts [8].

The modern CRM was invented because customers differ in their preferences and purchasing habit and do not all share similar view on product and services needs. CRM enables firms to gain detailed understanding of their customers, allowing them to know how to respond to customer needs and how to market products and services more effectively. CRM has evolved both in its functionality and adoption in more recent years [5]. According to [9], CRM strategy ranks among the top five corporate objectives. [10] forecasts spending on social software to support sales, marketing and customer service processes to exceed $1 billion worldwide by year 2013. The rapid growth of CRM can be attributed to fierce business competition for valuable customers, economics of customer retention (life-time value) and technology advances [11,12]. Today, firms invest considerable resources in systems and strategies aimed at knowing their customers well by collecting and analyzing customer data. The rapid advances in information and communications technology provide greater opportunities for modern firms to establish, nurture, and sustain long term relationships with their customers.

The underlying premise of CRM is that firms need customer knowledge to effectively segment customers, develop and maintain long-term relationships with profitable customers, determine how to handle unprofitable customers, customize market offerings and promotional efforts. CRM systems basically enable firms to incorporate all aspects of their activities seamlessly so as to design strategies uniquely targeted to customer needs. If this is successful, a firm can provide better customer service, increase customer satisfaction and help sales staff close deals faster and create enduring competitive advantage [13-15]. Positive effects of CRM on firms’ competitive edge have been extensively discussed in the works of [16-20]. Basically, the focus of CRM strategies to leverage competitiveness of firms have been broadly categorized into three as acquisition of customers [21], retention of customers [22] and customer profitability [23]. Other research works like [24-27] have also looked into the critical success factors for CRM implementation.

2.2. Success Factor in CRM Implementation

Even with the great achievements and potential capabilities of CRM strategies, [6] regretted that the past 25 years have overemphasized the technology side of CRM with little consideration on process-and-people issues, which are intimately responsible for successful CRM implementation. CRM technology is often incorrectly equated with CRM and seeing CRM as a technology initiative is a key reason for CRM failure in many firms that have implemented CRM strategies [28,29].

In a survey of 1337 firms who have implemented CRM systems to support their sales force, [30] estimated that only 25 percent reported significant improvements in performance. CRM scholars have advanced reasons why a CRM system will fail to yield expected results. Two key reasons are lack of strategic planning prior to the implementation of CRM [31], and lack of capabilities to effectively integrate CRM technologies into the sales processes of a firm [32,33]. Arising from this failure [34] explored the factors that contribute to successful CRM strategy implementation as experienced by users in the private sector. They applied the resource-advantage (R-A) theory as a theoretical foundation to explaining the potential of CRM as an advantage-producing resource for sale management and factors contributing to a successful CRM implementation. The research concluded that CRM is a higher-order resource that is enabled by four organizational capabilities: organizational learning, business process orientation, customer-centric orientation, and tasktechnology fit (TTF). Where these capabilities are absent or in minimal consideration a firm’s ability to effectively implement CRM and to also attain a positional advantage may be limited.

Looking into why firms adopt CRM strategies, [35] identified the top three objectives of implementing CRM among US and European firms as gaining customer fidelity, providing a personalized service to customers and better knowledge of customers. If the objectives of CRM are to be realized, [36] argues that an integrated approach is needed for both the formulation and implementation of CRM strategy. Firms implementing CRM ideas need first identify the key levers that can ensure them a competitive advantage. The centrality of CRM strategies should be on components that can produce competitive advantage rather than the best practices also used by rival firms. Since CRM is a strategic approach to customer service management, it is very important to consider setting the objective in line with the firm’s cooperate strategy rather than at the functional units. A holistic view of how, where and when CRM can be implemented so as to enhance customer experience is key to realizing CRM objectives [37].

[37] advanced three important considerations central to formulating CRM strategy as: 1) strategic implementation with a clear business goal; 2) agendas driven by insight into customers and demand patterns; and 3) enterprise-wide approach to customer management to coordinate tailored treatment of customers based on their value and needs. If the CRM strategy is not developed in such a way that it suits the customer it could have a negative impact on the sales force and loyalty of the customers. A customer-centric management system helps the firm to focus attention on customer identification, customer interactions and service, and customer differentiation as well as deploy expertise from different functional areas of the firm to promote the quality of customer experience [31,38]. As it is required that CRM strategy be customer-centric, it must also take into consideration the ability of personnel to effectively handle CRM technologies deployed by the firm. This tasktechnology fit can be achieved through customization of packages and adequate training [34]. At the level of implementation, [36] identified four critical elements for successful CRM implementation as; CRM readiness, CRM change management, CRM project management and employee engagement. A CRM implementation program may be judged as successful when CRM assists a firm to profitably deliver market offering to customers that 1) provide values to customers at a lower cost (relative to competition); 2) provide more value at the same relative cost (relative to competition), or provide more value at a lower cost (relative to industry competition) [39].

2.3. Classification and Components of CRM

Following [40], there are four classifications of CRM namely: operational CRM; analytical CRM; collaborative CRM and e-CRM. Operational CRM entails collection of customer data at the different touch-points of contacts through which firms interact with their customers (mail, sales force, contact center, fax, web, contact management systems, etc). The data obtained are then stored and arranged in a customer database. At technology level, operational CRM entails the automation of customer-facing aspects of the business with particular emphasis on marketing automation, sale force automation, and service automation [11]. Analytical CRM refers to firm-level processes involved in analyzing customer and market-level information to provide the intelligence and insights that guide a firm’s strategic marketing, CRM, service, and go-to-market choices [41]. Data obtained through operational CRM touch-points are analyzed so as to generate customer profiles, identify their behavioral patterns, service level determination, and support the segmentation of customer. Collaborative CRM is a hybrid of operational and analytical CRM. According to [42] the systems are integrated with enterprise-wide systems to allow a greater responsiveness to customers throughout the relationship units between customers and the firm. [41] in their enterprise-level CRM model and processes, integrates the two processes (Operational and Analytical CRM) by embedding the sales force in the context of an organizational-wide focus while the customer is placed at the center. e-CRM enables information on customers to be available at all touch-points between a firm and among its external business counterparts basically through the Internet and Intranet. The focus of e-CRM is emplacing a forum with which internal (firm) and external users can share customer information through the Internet or Intranet and to carry out other electronic commerce transactions.

CRM consists of several components that are essential to the firm implementing it. The recent trends in the development of CRM have enabled users to combine these components for a better result. [43] categorizes these components as time management, sales/sales management, telemarketing/telesales, customer contact centre, e-marketing, business intelligence, field service support, e-business, multimodal access, data sharing tools. These components have also been classified into front-end and back-end systems. The front-end systems are customer facing side which is more of operational CRM. The backend deals with analytical CRM where stored customer data are analyzed so as to segment them and make strategic moves aimed at offering the customer a valued-packed service.

3. Result and Analysis

CRM Perception and Implementation

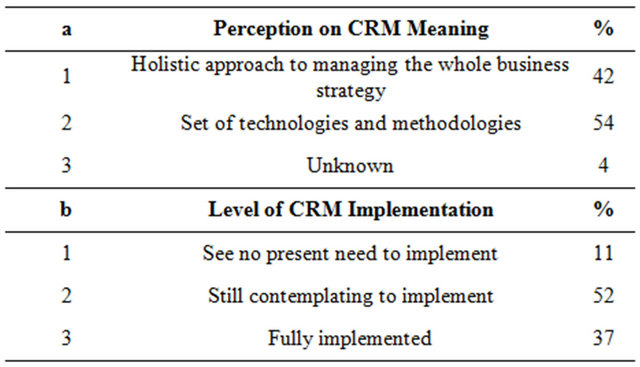

The concept of CRM, though a very recent adoption, is generally well known to retail business firms in Nigeria. As summarized in Table 1(a), two perceptions of CRM were generally held showing that firms are quite familiar with the concept. The greater percentage of 54% held the strict technology view of CRM defining it as a set of technology and methodologies for managing customer relationship. 42% held the view that CRM is a holistic business strategy of managing customer cutting across functions within the organization. Very few firms (4%) were neither familiar with the concept nor hoping to adopt it very soon. Research results have shown that the adoption of CRM does not translate linearly into substantial performance improvement. Much of the failure in CRM strategy has been attributed to equating CRM with CRM technology [28,29]. By adopting a technology view of CRM a large percentage of firms in the retail business in Nigeria demonstrated partial understanding of CRM as an advantage-producing resource that significantly imTable 1. CRM: Meaning and implementation.

proves performance when it integrates people, process and technology. When the strategic orientation of CRM as opposed to the technology orientation is adopted in the introduction of CRM, a process of strategic thinking is triggered for the planning and acquisition of essential organizational capabilities: organizational learning, business process orientation, customer-centric orientation and task-technology fit, that are critical for CRM strategy success.

As information on product offerings becomes more available to customers and marketing reach expands, customers become more mobile and unpredictable in their buying behavior. Competition among firms to keep loyal customers and win new ones becomes intense. The intensity of competition in the retail business sector in Nigeria may be gauged by the level of commitment of firms to manage customer relationship through implementation of CRM strategy. Table 1(b) implies a low intensity competition in the sector.

52% of the firms at the time of completing this research are still contemplating implementing CRM strategy and 11% have no compelling need to do so at this time. It is considered here that those supermarkets (37%) have fully implemented CRM strategy has not significantly improved performance through the delivery of superior value to customers. A business environment characterized by very keen and intense competition for customer retention and the benefits of implementing CRM strategy is significant in terms of improved performance will provide a strong pull effect for firms to implement CRM strategy. The competitive environment of the supermarket sector in Nigeria is not presently so intense as to confer very strong competitive advantage on implementing firms.

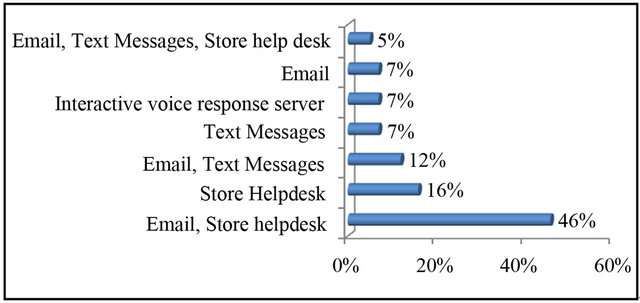

Another factor that may be responsible for non implementation of CRM by a large number of firms is the low level of e-readiness of firms. Among the firms surveyed about 65% do not have online presence. Services offered online by the rest 35% are generally limited to the display of corporate information and product categories with only about 3% offering provision for online ordering, however, without online payment. These services did not fully support an analytical CRM strategy aimed at collecting and analyzing a firm’s information regarding customers’ interaction, tracking individual customer behavior over time and using this knowledge to configure solutions precisely tailored to the needs of customers. A look at Figure 1 shows that supermarkets in Nigeria interacts with their customers principally through combinations of store help desks and e-mail (46%), short message services (Text Messages) and e-mail (12%), and store help desks as the largest single channel medium used to interact with customers. CRM as implemented by the firms is basically operational. Supermarkets collect

Figure 1. CRM media used by supermarkets.

customer data at the various points of contacts through which they interact with their customers (store help desks, e-mail and short message service). Our work finds no evidence of firm-level of processing and analyzing customer and market-level information to provide intelligence and insights for strategic action.

[44] have argued that though analytical CRM allow real-time capture of valuable customer data, it is unable to capture knowledge that the customer may have acquired elsewhere as well as capture customer preferences other than what has been pre-defined through websites. However, personal interaction with customers, unlike structured data gathered from transactions, lead to richer content that can help explain why customers behave the way they do. According to [45] customers know more about the firms they do business with than the firms knows about their customers. Thus, when the customers and salespersons or stores help desk come together, they both bring their knowledge and experiences to the interaction. If personal interactions with customers are properly managed, Nigeria supermarkets may improve performance by customer intimacy arising from extensive use of store help desks.

Though, the supermarkets may be lacking in structured data and its attendant benefits, the two-way exchange with customers reveals customer knowledge needs that the supermarkets may not be capturing. Meeting customers’ needs by taking time to listen to them and later providing knowledge will foster the relationship between the customers and the firm [44]. The ultimate goal is to transform these relationships into greater profitability by reducing customer acquisition costs, increasing repeat purchases, and charging higher prices [12].

Anchoring CRM strategy principally on personal interactions with customers is supported by the work of [46] Nonaka posited that informal relationships and the tapping of subjective insights, intuitions, and hunches of people could eventually lead innovative products.

Examining the supermarkets for objectives of implementing CRM, we found that the firms have clear cut goals and are driven by insight into customers’ needs and demand pattern. The firms surveyed clearly identified their three top goals of CRM implementation as: 1) gaining customer fidelity; 2) provide personalized services to customers; and 3) have better knowledge of the customers. However, as [37] suggested, implementation was not on enterprise wide scale. In the face of very low online presence of supermarkets in Nigeria (35%) personal interaction and not analytical CRM strategy will be more appropriate to achieving the goals of CRM set by the firms. While transactional data used in analytical CRM is useful to identify problems and preferences, it is difficult to determine the reason for customer decisions. With personal interactions, which require less investment in online presence, the supermarkets can ask customers directly and have an idea of the sources of problems, preferences, and needs. The leverage offered by personal interactions over analytical CRM (less investment in technology upgrade and learning, less worry on technology-task fit, low cost of knowledge sharing etc) appeared to have been the attraction of supermarkets in Nigeria.

4. Conclusion

The process of collecting and analyzing a firm’s information regarding customer interactions in order to enhance the customers’ values to the firm may be analytical or by personal interactions or both. Supermarkets operating in Nigeria may have chosen to grow customers’ value through personal interactions due to the high cost of investment in analytical CRM infrastructure and low level of dynamic capability to integrate infrastructure into people and processes. However, there are extensive literature support for enhancing customer loyalty and increasing switching costs through personal interactions. Due to the present infrastructure deficit in the country and low intensity of competition for customers’ loyalty, the huge investments in analytical CRM are considered uncalled for by the firms. As more big players, especially foreign firms join the sector and competition becomes more intense, firms may consider investing in analytical CRM and the attendant learning. For the present time, having good processes and systems to manage customer knowledge gained through personal interactions will deliver the benefits CRM suited to the present competitive environment.

REFERENCES

- S. M. Shugan, “Brand Loyalty Programs: Are They Shams?” Marketing Science, Vol. 24, No. 2, 2005, pp. 185-193. doi:10.1287/mksc.1050.0124

- D. Weatherspoon and T. Reardon, “The Rise of Supermarkets in Africa: Implications for Agri-Food Systems and Rural Poor,” Development Policy Review, Vol. 21, No. 3, 2003, pp. 1-17. doi:10.1111/1467-7679.00214

- L. Botha and H. Schalkwyk, “An Inquiry into the Evolving Supermarket Industry in Africa,” International Food & Agribusiness Management Association’s 17th Annual World Symposium, Parma, 23-26 June 2007, pp. 1-13.

- T. Reardon, J. Berdegue, M. Lundy, P. Schutz, F. Balsevich, R. Hernandez, E. Perez, P. Jano and H. Wang, “Supermarkets and Rural Livelihoods: A Research Method,” Staff Paper, Michigan State University, East Lansing, 2004.

- K. Sanjeev, A. Prabhu and T. Tom, “Quantitative Model for CRM Performance,” Journal of International Technology and Information Management, Vol. 17, No. 2, 2008, pp. 99-110.

- B. Goldenberg, “CRM: The Past and the Future,” Customer Relationship Magazine, Vol. 10, No. 1, 2006, p. 18.

- D. Goodhue, B. Wixom and H. Watson, “Realizing Business Benefits through CRM: Hitting the Right Target In the Right Way,” MIS Quarterly Executive, Vol. 1, No. 2, 2002, pp. 79-94.

- E. Riyad, “Towards a Successful CRM Implementation in Banks: An Integrated Model,” The Service Industries Journal, Vol. 27, No. 8, 2007, pp. 1021-1039. doi:10.1080/02642060701673703

- S. Nelson, “CRM Is Dead; Long Live CRM,” In: J. Freeland, Ed., Defying the Limits, Montgomery Research, 5th Edition, John Freeland, San Francisco, 2004, pp. 194-195.

- Gartner, Inc., “Gartner Says Spending on Social Software to Support Sales, Marketing and Customer Service Processes Will Exceed $1 Billion Worldwide by 2013,” Gartner, Inc., Connecticut, 2011.

- F. Buttle, “Customer Relationship Management: Concept and Tools,” Elsevier Butterworth-Heinemann, Oxford, 2004.

- R. Winer, “A Framework for Customer Relationship Management,” California Management Review, Vol. 43, No. 4, 2001, pp. 89-105. doi:10.2307/41166102

- K. Srivastava, S. Tasadduq and F. Liam, “Marketing, Business Processes, and Shareholder Value: An Organizationally Embedded View of Marketing Activities and the Discipline of Marketing,” Journal of Marketing, Vol. 63, No. 4, 1999, pp. 168-179. doi:10.2307/1252110

- Y. Cho, J. Hiltz and J. Fjermestad, “An Analysis of Online Customer Complaints: Implications for Web Complaint Management,” Proceedings of the 35th Hawaii International Conference on Systems Science, Los Alamitos, 7-10 January 2002, pp. 2308-2317.

- A. Kamakura and M. Wedel, “Market Segmentation: Conceptual and Methodological Foundations,” 2nd Edition, Kluwer Academic Press, New York, 1999.

- Y. Xu, D. Yen, B. Lin and D. Chou, “Adoption of Customer Relationship Management Technology,” Industrial Management and Data Systems, Vol. 102, No. 8, 2002, pp. 442-452. doi:10.1108/02635570210445871

- S. Hart, G. Hogg and M. Banerjee, “Does the Level of Experience Have an Effect on CRM Programs? Exploratory Research Findings,” Industrial Marketing Management, Vol. 33, No. 2, 2004, pp. 549-560. doi:10.1016/j.indmarman.2004.01.007

- M. Kennedy and A. King, “Using customer Relationship Management to Increase Profit,” Strategic Finance, Vol. 85, No. 9, 2004, pp. 36-42.

- G. Alvonitis and N. Panagopoulos, “Antecedents and Consequences of CRM Technology Acceptance in the Sales Force,” Industrial Marketing Management, Vol. 34, No. 4, 2005, pp. 355-368. doi:10.1016/j.indmarman.2004.09.021

- T. Tellefsen and G. Thomas, “The Antecedents and Consequences of Organizational and Personal Commitment in Business Service Relationship,” Industrial Marketing Management, Vol. 34, No. 1, 2005, pp. 23-37. doi:10.1016/j.indmarman.2004.07.001

- P. Kotler, “Marketing Management: Analysis, Planning, Implementation, and Control,” Prentice Hall International, Upper Saddle River, 1997.

- H. Peck, A. Payne, M. Christopher and M. Clark, “Relationship Marketing—Strategy and Implementation,” Butterworth Heinemann, Burlington, 2004.

- I. Gordon, “Relationship Marketing: New Strategies, Techniques and Technologies to Win Customers You Want and Keep Them Forever,” John Wiley and Sons, Hoboken, 1998.

- D. Justla, J. Craig and P. Bodorik, “Enabling and Measuring Electronic Customer Relationship Management Readiness,” Proceedings of the 34th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Maui, 3-6 January 2001, p. 7023.

- M. Abdullah, A. Al-Nasser and N. Husain, “Evaluating Functional Relationship between Image, Customer Satisfaction and Customer Loyalty Using General Maximum Entropy,” Total Quality Management, Vol. 11, No. 4, 2002, pp. 4-5.

- J. Fjermestad, C. Nicholas and J. Romano, “An Integrative Implementation Framework for Electronic Customer Relationship Management: Revisiting the General Principles of Usability and Resistance,” Proceedings of the 36th Annual Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Los Alamitos, 6-9 January 2003, p. 183.

- R. Ocker, and S. Mudambi, “Assessing the Readiness of Firms for CRM: A Literature Review and Research Model,” Proceedings of the 36th Annual Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Los Alamitos, 6-9 January 2003, p. 181.

- H. Kale, “CRM Failure and the Seven Deadly Sins,” Marketing Management, Vol. 13, No. 5, 2004, pp. 42-46.

- W. Reinartz, M. Krafft and W. Hoyer, “The Customer Relationship Management Process: Its Measurement and Impact on Performance,” Journal of Marketing Research, Vol. 41, No. 3, 2004, pp. 293-305. doi:10.1509/jmkr.41.3.293.35991

- J. Dickie, “Does CRM = Sales Effectiveness or Sales Ineffectiveness?” IT Toolbox, Scottsdale, 2005.

- G. Day, “Capabilities for Forging Customer Relationships,” Marketing Science Institute Working Paper, Cambridge, 2000.

- R. Erffmeyer and D. Johnson, “An Exploratory Study of Sales Force Automation Practices: Expectations and Realities,” Journal of Personal Selling & Sales Management, Vol. 21, No. 2, 2001, pp. 167-175.

- C. Speier and V. Venkastesh, “The Hidden Minefields in the Adoption of Sales Force Automation Technologies,” Journal of Marketing, Vol. 66, No. 3, 2002, pp. 98-112. doi:10.1509/jmkg.66.3.98.18510

- P. Raman, C. Wittmann and A. Rauseo, “Leveraging CRM for Sales: The Role of Organizational Capabilities in Successful CRM Implementation,” Journal of Personal Selling and Sales Management, Vol. 26, No. 1, 2006, pp. 39- 53. doi:10.2753/PSS0885-3134260104

- Institute of Direct Marketing-IDM, “The IDM Guide to CRM Mastery,” Institute of Direct Marketing-IDM, Middlesex, 2002.

- A. Payne and P. Frow, “Customer Relationship Management: From Strategy to Implementation,” Journal of Marketing Management, Vol. 22, No. 1-2, 2006, pp. 135-168.

- G. Larry, “The Role of Customer Intelligence in Successful CRM,” DM Review, 2004, pp. 12-14.

- D. Peppers and M. Rogers, “The One to One Future,” Doubleday, New York, 1999.

- D. Hunt and C. Lambe, “Marketing’s Contribution to Business Strategy: Market Orientation, Relationship Marketing, and Resources-Advantage Theory,” International Journal of Management Reviews, Vol. 2, No. 1, 2000, pp. 17- 34. doi:10.1111/1468-2370.00029

- M. Xu and J. Walton, “Gaining Customer Knowledge through Analytical CRM,” Industrial Management & Data Systems, Vol. 105, No. 7, 2005, pp. 955-971. doi:10.1108/02635570510616139

- F. John, A. Michael, W. Thomas and H. Charlotte, “CRM in Sales-Intensive Organizations: A Review and Future Direction,” Journal of Personal Selling & Sales Management, Vol. 25, No. 2, 2005, pp. 169-180.

- H. Kracklauer, D. Mills and D. Seifert, “Collaborative Customer Relationship Management: Taking CRM to the Next Level,” Harvard Business School Soldiers Field Boston, 2004.

- G. Barton, “CRM Automation,” Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River, 2002.

- M. García-Murillo and H. Annabi, “Customer Knowledge Management,” The Journal of the Operational Research Society, Vol. 53, No. 8, 2002, pp. 875-884. doi:10.1057/palgrave.jors.2601365

- Y. Butler, “Knowledge Management: If Only You Knew What You Knew,” The Australian Library Journal, Vol. 49, No. 1, 2000, pp. 31-42.

- I. Nonaka, “The Knowledge Creating Company,” Harvard Business Review on Knowledge Management, Harvard Business School Press, Cambridge, 1991, pp. 21-46.