Theoretical Economics Letters

Vol.06 No.05(2016), Article ID:70693,14 pages

10.4236/tel.2016.65099

Product Repositioning in the UK Newspaper Industry

Stefan Behringer

Mercator School of Management, Universität Duisburg-Essen, Duisburg, Germany

Copyright © 2016 by author and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY 4.0).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received: August 1, 2016; Accepted: September 17, 2016; Published: September 20, 2016

ABSTRACT

This paper investigates the alleged predatory behaviour in the UK quality newspaper industry in the 1990s in terms of product repositioning using a horizontal differentiation model and industry data. It supports the call for an “effects based” approach to competition law by showing that non-price conduct can be a critical and less visible, complementary means to achieve a predatory goal than mere price cuts.

Keywords:

Spatial Predation, Location Models, Product Repositioning, Predatory Pricing

1. Introduction

In this paper, I investigate a case of alleged predatory behaviour in the UK which has received much attention in the 1990s, namely the “price war” in the weekly quality broadsheet newspaper industry. The public discussion of this period has portrayed it exclusively as being a case of presumed predatory pricing. I argue instead that the newspaper industry is a prima facie case for an analysis that should be conducted in terms of the standard Hotelling location model of horizontal product differentiation. The adequacy of this model implies that there is an important non-price dimension to this case which a predator may use as an instrument to adversely affect a potential prey. It thus adds to the recent emphasis on models that investigate product repositioning as a strategic tool (see e.g. Pakes, [1] ) which amounts to what could be called “spatial pre- dation”.

Predatory behaviour is commonly defined as a strategic mechanism through which a firm attempts to inhibit a competitor, usually by reducing its profitability, and in parti- cular to induce market exit. Traditionally such behaviour has received a thorough discussion within the “Law and Economics” literature and more recently within game theoretic models in industrial economics. These discussions carry important implica- tions about the design and purpose of an efficient competition policy and antitrust law1.

The economic theory literature contains numerous models that capture examples of predatory behaviour such as signaling and reputation models that build on the exis- tence of asymmetric information. Alternatively, deep pocket predation tries to rationalize short run costly price wars under perfect information on the product market but re- quires some capital market imperfection (financial predation) and barriers to prevent the prey from re-entering once the predator tries to recoup its losses. Some models of predatory behaviour also look at non-price conduct such as predatory product innova- tion or preannouncements. The heterogeneity of rationales to be investigated under the “ predation” heading is thus substantial.

Arguing in favour of a more economics and “effects-based” rather than “form-based” approach to EU Competition Law, Gual, et al. [4] identify a set of economically sound predation mechanisms: focusing on financial predation, signalling, and reputation me- chanisms2. This allows for a simplification of the analysis but it is vital to note that such mechanisms can employ a wide set of strategic instruments. What complicates the matter for investigators further is that conversely, using price as the instrument, any of the economically sound predation mechanisms may be employed.

Much of the legal focus in actual cases has traditionally been on pricing conduct and in particular the Areeda-Turner pricing rule of “ pricing below cost”. Whereas this rule served as the simple standard test for predatory behaviour in the courtroom it has been noted that the rule is insufficient for two-sided markets such as newspapers (e.g. see Wright [6] or Anderson and Gabszewicz [7] ). For a recent proposal of how to use the rule in the context of two-sided markets see Behringer and Filistrucchi [8] .

The objective of this paper is to support the call by Gual, et al. [4] by showing that non-price conduct can be a critical and less visible3, complementary means to achieve a predatory goal than mere price cuts. Looking at circulation and pricing data from the period I am able to “bring data to the model” and find that this second, non-price dimension explains much of the damage done to the prey’s profit in this period.

2. The UK Newspaper Industry in the 1990s

During the early 1990 the UK quality broadsheet newspaper industry composed of The Times, the Independent, the Guardian, and the Daily Telegraph, has seen a relatively homogenous and stable pricing pattern for weekly editions. Then, on the 6. September 1993 News International Newspaper Ltd. (NIN) recently acquired by Rupert Murdoch decided to cut the price for The Times from 45p to 30p, thereby undercutting the Guardian at 45p, the Independent at 45p, and the Daily Telegraph at 48p. Public perception had it that a “price war” in the quality newspaper industry had begun.

Before deciding on its drastic price cut, NIN had run a price experiment in Kent County which showed the following changes in circulation after three weeks: The Times was up 13.8%, at the expense of between 5% and 6.8% losses incurred by Inde- pendent and Guardian and up to 2.6% losses incurred by the Telegraph.

The Independent, quoting a media analyst conjectured that the price cut was directed against its market share. “When the Independent was launched in 1986, it took more readers from The Times than the Guardian or the Telegraph’ (...) It has been the Independent holding back The Times ever since”4. Immediately after the announce- ment, Robin Cook, then the Labour party’s trade and industry spokesman wrote to the Office of Fair Trading (OFT) demanding an inquiry into possible unfair competition. The Independent estimated that at the current level of circulation of around 350,000 (August 1993) this price cut came at a cost to The Times of about £50,000 per day.

Bryan Carsberg, director general of the OFT observed “with interest” the alleged newspaper “price war” that Mr. Murdoch ignited. His office’s definition of predatory pricing―the deliberate acceptance of losses in the short term with the intention of eliminating competition so that enhanced profits may be achieved in the long term― looks prima facie as if it may indeed apply to the battle between the loss-making Times and the struggling Independent.

Because of its substantial financial difficulties, the Independent decided to raise its price from 45p to 50p on the 12. October 1993 but then came under even more pressure as the Telegraph under Conrad Black also decided to drop its price from 48p to 30p on 1. August 1994.

Due to the increasing financial strain, the editor of the Independent, Andreas Smith, put the Independent on a one-day sale for 20p and put a strong personal statement into his paper trying to keep the readers: “We remain dedicated to journalism of the highest quality and integrity. Readers will understand that this can never be cheap”, thus raising public awareness of the alleged predatory behaviour of The Times5. The Guar- dian was argued to be relatively unaffected due to its market niche position.

On 24. June 1994, The Times decreased is price again from 30p to 20p. By this time the issue has received strong political attention. Tam Dalyell, Labour MP said it was an issue of “the quality of democracy”, and Tony Wright, Labour MP said that the use of monopoly power to drive out competitors was “offensive” to the public interest. A plurality of opinion was vital. Robin Cook demanded that the OFT should come up with a decision in favour of predatory behaviour since Bryan Carsberg had been talking about a thin dividing line between normal and aggressive competition and with the new price cut this line now surely had been crossed.

The Independent quotes Dalyell’s estimates that of the 20p The Times received for each copy, 17.5p went to wholesalers and retailers and the cost of printing a copy was 15p. “This is a £ 30 m a year subsidy”6. The Independent reacted on the 1. August 1994 and reduced its price from 50p to 30p permanently in order to stop the decline of its circulation that decreased by 20% since The Times had first reduced its price. Its financial situation was known to be severe. In the beginning of 1994 a substantial refinancing had to take place which prevented the paper from being taken over from Carlo de Benedetti, another newspaper tycoon.

On 21. October 1994, the OFT issued a decision in the case. Bryan Carsberg said that his inquiry into the price cuts had not established a case for formal action under the competition legislation. In the OFT release he is quoted:

“The structure and characteristics of the market for national daily newspapers suggest that predation is unlikely to prove a feasible strategy for the owners of the Daily Telegraph or The Times. The cover price reductions have had wide-ranging effects on other newspapers, national broadsheets, mid-market titles and regional newspapers, and appear not to be targeted upon any particular title. In view of the number of competing titles, it does not seem likely that a predator would be able to recoup any losses out of supra-normal profits in the future. (...) The Times has been making losses for many years. (...) The Times’ decision to reduce cover prices appears to be a reasonable commercial strategy designed to improve its compe- titive position in prevailing market circumstances.”7.

Subsequently there was a period of increase in cover prices as the costs of news printing were rising for all firms. The Times decided to increase its prices from 20p to 25p on the 3. July 1995 and at the same date the Daily Telegraph also increased from 30p to 35p. The Independent followed on the 17. July and increased its price to 35p. Another wave of price increases was initiated by The Times and the Daily Telegraph on the 20. November 1995 who raised their prices to 30p and 40p respectively. The Inde- pendent leapfrogged on the 22. January 1996 ending a period of rapid price fluctuations that lasted for 29 months.

The exact consequences of the alleged price war period are a matter of vigorous public disagreement. In fact no consensus emerged even to who the alleged predator The Times was preying against. The data shows the following picture between August 1993 and January 1996: The Times has increased circulation market share from about 17% to 28%. The Independent has moved from 16% to 12% and the Daily Telegraph has moved from 49% to 43%. The market share of the Guardian has moved very little. Looking at these figures one has to keep in mind that the prices of The Times are still 15p, that of the Independent and the Daily Telegraph 5p lower than in 1993.

3. The Data

The circulation data covers total monthly circulation figures and cover prices for the Guardian, the Independent, The Times and the Daily Telegraph from 1990 to 2000 for a total of 132 months8. The data on market shares is depicted in Figure 1, the data on

prices in Figure 2 and Figure 3. In all figures the horizontal axis depicts the months running from January 1990 (1), to December 2000 (134). Figure 1 has market shares as a fraction of one, Figure 2 and Figure 3 have prices in Pounds Sterling on the vertical axis.

4. Location Model

I set out to shed some light upon issues of the alleged predation using the Hotelling location model. The model is conceptually very simple but fits the localized competition of the newspaper market quite well. The product differentiation is assu-

Figure 1. Market shares.

Figure 2. Prices I.

Figure 3. Prices II.

med to be one dimensional and firms can charge different prices influencing the posi- tion of marginal consumers drawn from some distribution function over the charac- teristic space which I simplify to be the real line. The standard “transport cost” para- meterized by t is thus a shared disutility that occurs if a reader does not consume the newspaper that exactly corresponds to her most preferred variety.

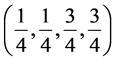

Mathematically the model can become very complex once locations of the firms on the characteristic space are no longer fixed. For example, given a uniform distribution of consumers, and two firms the only pure strategy Nash equilibrium (NE) in location

is , but with three players no pure strategy NE exists. With four players the only NE is

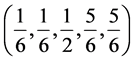

, but with three players no pure strategy NE exists. With four players the only NE is  with five the only NE is

with five the only NE is  but then equilibria become much more complex.

but then equilibria become much more complex.

Given that both locations and prices are chosen calculations get even more involved. Also almost all theoretical models assume that there are only two firms and if the n-firm case is analyzed symmetry assumptions about substitution patterns or the use of a circular characteristic space (e.g. Sutton [10] ) erase many of the realistic properties of the simple model for the newspaper industry.

The characteristic space on which the newspapers can position their products is the political position of the paper and I assume that consumers are standard normally distributed over this space. It is common consensus that the four British quality broadsheets can be ordered as the Guardian, the Independent, The Times and the Daily Telegraph on the political line ranging from Centre left to Centre right. Note that given this interpretation a circular characteristic space that simplifies endpoint problems makes little sense.

A full characterization of the theoretical setup with more than two firms, variable location, variable price, and endpoints implies an analytical challenge. A full analytical analysis that looks at equilibria with four firms can be found in Behringer and Filistrucchi [11] . Instead here I investigate the alleged predation issue by putting real data to the model, using a spreadsheet approach.

I use data of the industry from 1990 to 2000, that contain prices and market shares. Assuming that consumers are fully rational and maximize their welfare allows to determine the position of the marginal consumers from the realized circulations for given prices. The standard focus on price predation will not allow for myopic profit maximization but has to take into account exit probabilities and recoupment periods which I simplify here by assuming that firms behave non-strategically.

On the contrary I am able to show, given that prices and locations do influence circulation as in the Hotelling model, to what extent the strategic location on the Hotelling line, e.g. a move in the newspaper’s political position, can be used as a means to “spatially predate” against a prey. Note that unless a more complete analysis of the market and profits as outlined below has been undertaken, such predation only implies a strategic (but less visible) move against a competitor which may be justified by standard competitive reasons.

In a Hotelling model with uniformly distributed consumers and a shared linear disu- tility from distance such product repositioning will be neutral with respect to the market shares of a predator. Given any prices, a move towards a competitor on the unit line just takes as many readers from the prey as it gives to the firm in the predator’s back- yard leaving the market share of the predator unaffected. This holds if the predator is not located next to the endpoints of the unit line and hence only if one has strictly more than two firms. One may also think about a situation where two non-boundary firms (or one firm owning two newspapers) on opposing sides of a prey “squeeze” the latter without cost which would be even more effective.

5. The Analysis

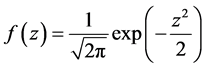

The model is a standard Hotelling model. I assume four firms (newspapers), the Guardian (G), the Independent (I), The Times (T), and the Daily Telegraph (DT) and a mass of consumers located on the real line with a density given by a standard normal distribution function  as

as

(1)

(1)

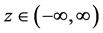

where . Demand is fully inelastic and consumers have utility

. Demand is fully inelastic and consumers have utility  from consuming the good and a quadratic cost (as proposed in d’Aspremont et al. [12] ) proportional to the distance between their location and that of the firm

from consuming the good and a quadratic cost (as proposed in d’Aspremont et al. [12] ) proportional to the distance between their location and that of the firm . The po- sition of a marginal consumer (

. The po- sition of a marginal consumer ( ) between two firms i and

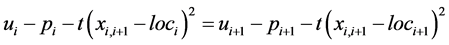

) between two firms i and  can be determined by the standard indifference condition

can be determined by the standard indifference condition

(2)

(2)

of the consumer located at . The position of the marginal consumers can thus be determined, and I am interested in the political position of the newspaper that has led to the observed market shares for given prices. This can be calculated as

. The position of the marginal consumers can thus be determined, and I am interested in the political position of the newspaper that has led to the observed market shares for given prices. This can be calculated as

As I assume that the fixed benefit of consumption for given prices

and the formula can be used recursively to obtain the other newspaper’s locations. As all formulae involve the location of another firm solving for the locations that satisfy the maximization implies one degree of freedom. Market shares

for the upper limit of the integral

I now proceed to use Formula (4) recursively to determine the location of the four newspapers on the political line given their choices of prices. The degree of freedom in the analysis is taken into account by fixing the location of the Guardian exogenously. This is a priori restrictive but the Guardian was not involved in the price war and is generally perceived to have an uncompromising and invariant political position. Furthermore an alternative symmetric specification is tested below.

I thus first determine

with

and then proceed recursively to solve out for the remaining locations using a spreadsheet analysis. The outcome, taking into account the varying pricing regimes and market share movements reveal the implied locations as given in bold lines in Figure 4 where again months from January 1990 to December 2000 are located on the horizontal axis and the locations of the indifferent consumers given by the dotted lines.

The analysis of the data thus allows for the following interpretation: The Times left its almost Centrist position in the early 90s following the acquisition of Murdoch leaning more and more towards the political Left. This move towards the Left of the political spectrum implied an increased competition for both the Independent and the

Figure 4. Locations I.

Guardian who were unable to accommodate and lost market share. The very significant gain in market share of The Times however was also caused by the Daily Telegraph who has moved substantially towards the political Right during the decade allowing for a more relaxed competition for The Times on this side of the market.

Clearly any more detailed causal inference is not valid on the grounds of this purely descriptive analysis taking firm decisions as exogenous and market shares at the (price adjusted) outcome of the Hotelling model. However it is clear that the location deci- sions of The Times away from the mode of the distribution of consumers and towards the Independent led to an increasing pressure on the latter with the Guardian’s position assumed unchanged. Whereas moving from the mode of consumer comes at a cost at equal prices, spacial predation against a prey with a higher price and quadratic disutility in a move away from the mode may even be profitable taking more from the prey than losing in ones backyard.

In a second modelling attempt I relax this assumption and resolve the issue of the degree of freedom differently over time by also allowing the location of the Guardian to

vary. In the first period

(6). In the following periods

and

for

location. This way I can obtain results that are qualitatively identical.

6. Separating the Price Effect

As can be seen from (4), the details of a quantitative analysis are sensitive to the choice of the heterogeneity parameter t. A high value will imply that only market share effects influence the solved out positions of the firms’ location decisions. Given that the parameter is low, price differences have a relatively more important effect on implied locations. In this section I compare the combined effect as predicted by the Hotelling model with the extreme case of a pure location effect where I look at very large t (L).

Technically I can make the analysis more sensitive w.r.t. price changes using lower t values in the spreadsheet computations but I get into problems once the term under the roots in (4) becomes negative. To remain in the Hotelling picture, one “ umbrella” undercuts the other fully and there is no intersection, and hence position of the marginal consumer, given differing prices. Hence in the above analysis depicted in Figure 4 I have chosen t as low as possible under the condition that the roots remain positive. Note that due to the symmetry of this parameter for all firms this allows us to compare the relative importance of price versus market share effects. From Figure 5 one can see that the conclusion that there is a move of The Times towards the Inde- pendent holds true, even if one completely abstracts from price effects. Under these conditions the locations of the firms are given by the dotted lines. The result of the previous section is thus robust.

As argued before for the uniform distribution case with linear shared disutility and any given prices, when a non-boundary predator moves towards a prey this is neutral for its circulation. Thus non-boundary firms cannot affect their circulation unilaterally by location choice whereas a boundary firm can always gain market share by moving away from the boundary. Note that the Independent is not a boundary firm even if one holds the location of the Guardian fixed.

Figure 5. Locations II.

The Times’ move towards the Independent increases competition for the latter but benefits the Daily Telegraph. This allows for the Daily Telegraph to move to the political

Right without losing too much market share to The Times (resulting from its boundary position) with The Times gaining most market share.

I also observe two qualitatively separate phases of the alleged price war, the price cut of The Times to 30p from months 47-56 (September 93-August 1994) with the Inde- pendent increasing its price and the Daily Telegraph staying put) and The Times cut to 20p from periods 57-68 (July 1994-June 1995) where the Independent and Daily Telegraph follow simultaneously by cutting price to 30p in month 58 (August 1994). Taking into account the price change in the first phase shows that locations of the Daily Telegraph and The Times have not changed much neither towards the Daily Telegraph nor the Independent. Price changes alone can explain what happens to market shares and its importance can be seen by the large differences in locations with small and large t. A relative price advantage of The Times implies, ceteris paribus, that the real price adjusted location of the Independent is even further away from The Times.

Looking at the second phase changes things: The price advantage of The Times increases again but now with the real location of The Times being much closer to the Independent. Here, very little of the observed changes result from the changes in prices as can be seen by the small differences with small and large t and location effects dominate what happens to market shares. As The Times final location is now much closer to the Independent than before the alleged price war this opens the possibility for there being “spatial predation” in addition to the alleged price predation.

Again, the Times move towards the Independent in the political dimension would decrease its market share given similar prices as it is a move away from the mode of the consumer distribution. However its market share improves, not only at the expense of the Independent (who hardly moves either with or without taking price changes into account) but due to the Daily Telegraph who takes the chance to move further to the right reducing its captive consumers.

To summarize: Whereas the first phase of the alleged price war consisted in a solitary cut in price by The Times, the second phase which implied another substantial price cut was accommodated by price cuts of its competitors flanked by “spatial predation”, i.e. a clear move towards the political Left increasing the pressure on the Independent. This strategic move which given similar prices implies a loss in market share for the predator was made less costly by the continuing rightward move of the Daily Telegraph reducing the latter’s share of captive consumers.

The assumptions of the Hotelling model underlying the result deserve some further comments. The model implies a focus on market shares and not on absolute circulation quantities. The Hotelling model assumes that consumers demand is fully inelastic. In fact, the total circulation numbers are quite stable over the 90s possibly also due to the fact that many newspapers are sold in subscriptions. The fact that I am investigating a period with substantial overall price decreases relaxes the constraint imposed by this assumption. Also the assumption of normality does not affect the qualitative result about The Times relocation. Any distribution that is not significantly skewed will yield the same outcome qualitatively.

It is indisputable that there are alternative possibilities to link the alleged predatory behaviour of The Times with modern economic theory. Essentially this analysis uses a static model in order to explain a dynamic phenomenon. In line with standard repeated game analysis and looking at the pricing strategies one may interpret the alleged predatory period as the end of a collusive period in quantities in the standard Green and Porter [13] type analysis.

Promising is also the attempt to recognize the newspaper industry as a typical case of a two-sided market (for surveys see Armstrong [14] and Anderson and Jullien [15] . In particular treatments similar to Argentesi and Filistrucchi [16] and Kaiser and Wright [17] that also look at the publishing industry seem to be applicable. A price war (and the implied loss of sales revenue) may then be intended to increase circulation which may in turn imply an increase in advertising revenue. Clearly below cost prices can then be non-predatory (as defined by the Areeda-Turner rule) if the loss of revenue from readers can be made up by the increase in advertising revenue resulting from higher circulation. The analysis of the allegedly predatory period in the UK newspaper industry can be performed along such lines if data on advertising revenue is available over the relevant period. Such an analysis is currently undertaken in Behringer and Filistrucchi [18] .

7. Conclusions

In order to distinguish illegal from competitive behaviour, Gual et al. [4] on page 23 of their guidelines for interpretation of EU law claim that modern legal analysis, incor- porating the findings of economic theory, should “carefully identify a precise story of competitive harm and the restrictions on the facts that need to be established in order to substantiate it”.

As emphasized by the authors, subscribing to some form of an economically sound predatory mechanism, here financial predation, (with all the necessary conditions attached that need to be checked such as capital market imperfections and the ability to recoup losses in subsequent periods) legal investigators and competition authorities should not be confused by the variety in the set of strategic tools employed. As shown above, financial predation can be implemented by choosing from different instruments that may allow for substitution but may also be complementary as in our case and not only by employing price strategies.

Focusing on price predation as the prima facie case for predatory behaviour and on a simple price cost rule as evidence for such price predation, (as out of fashion in the US but still practiced in EU case law) may misguide a coherent analysis of predatory behaviour that aims at harming competitor’s profits. The former approach ignores that efficient predatory behaviour may employ more sophisticated mechanisms, for example those based on information asymmetries. The second implies a focus on price as the major strategic instrument which ignores that many of the predatory mechanisms can be pursued using alternative instruments. The present analysis points to one such case.

Acknowledgements

This paper originated as the MSc thesis “Predation: Economic Theory and Case Study Evidence” at the London School of Economics with John Sutton. I am also grateful to Simon Anderson, Lapo Filistrucchi, Marco Gambaro, David Genesove, Martin Hellwig, Markus Reisinger, Patrick Rey, Joel Waldfogel, Julian Wright, and participants of the 5. Workshop on Media Economics in Bologna, the 6. ZEW Mannheim Conference on ICT and at WHU Koblenz for comments.

Cite this paper

Behringer, S. (2016) Product Repositioning in the UK Newspaper Industry. Theoretical Economics Letters, 6, 986-999. http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/tel.2016.65099

References

- 1. Pakes, A. (2016) Empirical Tools and Competition Analysis: Past Progress and Current Problems. International Journal of Industrial Organization.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijindorg.2016.04.010 - 2. Elzinga, K.G. and Mills, D.E. (2015) Predatory Pricing. In: Blair, R.D. and Sokol, D.D., Eds., The Oxford Handbook of International Antitrust Economics (Vol. 2), Oxford University Press.

- 3. Evans, D.S. and Schmalensee, R. (2013) The Antitrust Analysis of Multi-Sided Platform Businesses, No. w18783. National Bureau of Economic Research.

http://dx.doi.org/10.3386/w18783 - 4. Gual, J., Hellwig, M., Perrot, A., Polo, M., Rey, P., Schmidt, K. and Stenbacka, R. (2005) An Economic Approach to Article 82, Report by the Economic Advisory Group for Competition Policy, Bruxelles.

- 5. Bolton, P., Brodley, J. and Riordan, M. (2000) Predatory Pricing: Strategic Theory and Legal Policy. Georgetown Law Review, 88, 2239-2330.

- 6. Wright, J. (2004) One-Sided Logic in Two-Sided Markets. Review of Network Economics, 3, 44-64.

http://dx.doi.org/10.2202/1446-9022.1042 - 7. Anderson, S.P. and Gabszewicz, J.J. (2005) The Media and Advertising: A Tale of Two-Sided Markets. In: Ginsburgh, V. and Throsby, D., Eds., Handbook of Cultural Economics, Elsevier Science.

- 8. Behringer, S. and Filistrucchi, L. (2015) Areeda-Turner in Two-Sided Markets. Review of Industrial Organization, 46, 287-306.

- 9. Gentzkow, M. and Shapiro, J.M. (2006) Media Bias and Reputation. Journal of Political Economy, 114, 280-316.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/499414 - 10. Sutton, J. (2007) Market Share Dynamics and the “Persistence of Leadership” Debate. American Economic Review, 97, 222-241.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1257/aer.97.1.222 - 11. Behringer, S. and Filistrucchi, L. (2015) Hotelling Competition and Political Differentiation with More than Two Newspapers. Information Economics and Policy, 30, 36-49.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.infoecopol.2014.10.004 - 12. d’Aspremont, C., Gabszewicz, J.J. and Thisse, J.-F. (1979) On Hotelling’s Stability in Competition. Econometrica, 47, 1145-1150.

http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1911955 - 13. Green, E.J. and Porter, R.H. (1984) Noncooperative Collusion under Imperfect Price Information. Econometrica, 52, 87-100.

http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1911462 - 14. Armstrong, M. (2006) Competition in Two-Sided Markets. RAND Journal of Economics, 37, 668-691.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1756-2171.2006.tb00037.x - 15. Anderson, S.P. and Jullien, B. (2016) The Advertising-Financed Business Model in Two-Sided Media Markets. In: Anderson, S., Waldfogel, J. and Stromberg, D., Eds., Handbook of Media Economics, Elsevier Science.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-444-62721-6.00002-0 - 16. Argentesi, E. and Filistrucchi, L. (2007) Estimating Market Power in a Two-Sided Market: The Case of Newspapers. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 22, 1247-1266.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/jae.997 - 17. Kaiser, U. and Wright, J. (2006) Price Structure in Two-Sided Markets: Evidence from the Magazine Industry. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 24, 1-28.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijindorg.2005.06.002 - 18. Behringer, S. and Filistrucchi, L. (2016) Price Wars in Two-Sided Markets: The Case of the U.K. Quality Newspapers, Work in Progress.

NOTES

1For a recent survey of the theoretical findings see Elzinga and Mills [2] , for one that emphasizes the role of multi-sided platforms see Evans and Schmalensee [3] .

2This broad classification is shared with Bolton et al. [5] .

3However recent methodology aiming to detect “slant” in newspaper language may also be used to improve visibility of the means we focus on, see Gentzkow and Shapiro [9] .

4Independent, 3. September, 1993, “Media analysts say “Times” cut is commercial madness”.

5Independent, 23. June, 1994, “The Price War and your newspaper”.

6Independent, 21. July, 1994, “Newspaper War goes to Commons: MPs press Heseltine on Predatory Policy”.

7Office of Fair Trading (OFT), Press Release, 21. October 1994.

8Data on circulation come from those collected by the Audit Bureau of Circulation (ABC) National Newspaper Certification Audits for quality newspapers. Data on prices were collected using the Guardian’s (2005) communication “Newspaper price rises” that contains prices for all newspapers investigated.