Open Journal of Nursing

Vol.3 No.2(2013), Article ID:32476,11 pages DOI:10.4236/ojn.2013.32032

Factors influencing female patients’ recovery after their first myocardial infarction as experienced by cardiac rehabilitation nurses*

![]()

1School of Social and Health Sciences, Halmstad University, Halmstad, Sweden

2School of Health Sciences, Jönköping University, Jönköping, Sweden

Email: #inger.wieslander@hh.se

Copyright © 2013 Inger Wieslander et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Received 15 March 2013; revised 20 April 2013; accepted 10 May 2013

Keywords: Cardiac Rehabilitation Nurses; Myocardial Infarction; Recovery; Transition Process; Women

ABSTRACT

Background: In the developed part of the world, coronary heart disease is the major cause of death and is one of the leading causes of disease burden. In Sweden, more than 30,000 people per year are affected by myocardial infarction and out of these approximately 40% are women. Nearly 70% of the women survive and after a myocardial infarction a recovery process follows. Today’s health care focuses more on treatment, symptoms and risk factors than on the individuals’ perceptions of the recovery process. Aim: To explore cardiac rehabilitation nurses’ experiences of factors influencing female patients’ recovery after their first myocardial infarction. Methods: Twenty cardiac rehabilitation nurses were interviewed. The study was conducted using qualitative content analysis. Results: The cardiac rehabilitation nurses experienced that women’s recovery after a first myocardial infarction was influenced whether they had a supportive context, their ability to cope with the stresses of life, if they wanted to be involved in their own personal care and how they related to themselves. Conclusions: Women’s recovery after a myocardial infarction was influenced by factors related to surroundings as well as own individual factors. The underlying meaning of women’s recovery can be described as the transition process of a recovery to health. Our findings suggest that a focus on personcentered nursing would be beneficial in order to promote the every woman’s personal and unique recovery after a myocardial infarction. Finally, the cardiac rehabilitation nurses’ experiences of factors in- fluencing male patients’ recovery after their first myocardial infarction should be important to investigate.

1. INTRODUCTION

In the developed part of the world, coronary heart disease (CHD) is the major cause of death and is one of the leading causes of disease burden [1]. Myocardial infarction (MI) has long been seen as a male disease despite the fact that it is also a health problem for women [2]. In Sweden, more than 30,000 people per year are affected by MI and out of these approximately 40% are women. Nearly 70% of the women survive [3] and after an MI a recovery process follows [4].

European guidelines on cardiovascular health care emphasize the inclusion of secondary prevention [5]. It is important to note that secondary prevention care after an MI has not improved during the last 15 years at the same rate as acute MI care [6]. One reason could be that research and health care focus more on treatment, symptoms and risk factors and not on the individuals’ perceptions of the recovery process after an MI [4]. Today’s health care requires both preventative and health promotion interventions which emphasize that it is no longer enough to focus only on curing and alleviating disease [7]. A central part of secondary prevention is cardiac rehabilitation programs [CRP] in order to improve quality of life among patients [8]. The goals of CRP are to reduce the risk of relapse, promote lifestyle and health behaviour changes as well as to facilitate the patients’ recovery [3,5]. Research has shown that participation in CRP promotes patients’ health and quality of life as well as preventing new cardiac events [9]. However, women do not participate in CRP to the same extent as men [10, 11]. Women’s life situation after an MI is more likely to be affected negatively as they are, to a greater extent, more concerned about new cardiac events [12].

The concept of recovery can be defined in different ways depending on in which context, profession and culture it is used [13]. Recovery and rehabilitation are often used interchangeably [3], even though there is a distinct difference between them. Slade and Hayward [14] describe that recovery includes both personal recovery and clinical recovery. Clinical recovery, as well as the rehabilitation, focuses upon the reduction of symptoms and increased levels of functioning, which are more in line with the professional perspective [14,15]. Personal recovery can be seen as a multidimensional process [15] and as each person’s unique journey [14,16,17]. This unique journey is about the individual’s ability to adapt to the new situation after a disease and at the same time to have the power to develop their own new life situation. The person needs to have the opportunity to choose different ways in the recovery process in order to gain health [14,16,17]. Research on recovery and MI, shows that patients and health care professionals describe recovery as an on-going and enduring process that includes learning to adapt to a new life situation [18]. Women, despite illness, describe recovery after an MI as a gradual and personal process in which they face challenges with a combination of strengths, weaknesses and available resources to gain health [19].

A cardiac rehabilitation nurse [CRN] is an expert in both health promotion and in illness prevention [20]. In addition to an adequate knowledge of cardiology and cardiovascular nursing, a CRN has a central role in CRP [20,21]. However, empirical studies concerning nurses’ experiences of women’s recovery after a first MI are rare. Most previous research focuses on recovery from the women’s and their partners’ point of view [12,22-30]. Since CRNs meet many women who have experienced an MI, their experiences of the women’s recovery process may be an important complement in the daily work to support counseling female patients through their recovery process after their first MI. Accordingly the aim of the study was to explore cardiac rehabilitation nurses’ experiences of the factors that influence female patients’ recovery after their first MI.

2. METHODS

2.1. Design and Setting

The study had an explorative and descriptive design based on qualitative content analysis [31]. The interviews were carried out between April and December 2010 at 10 different hospitals (4 university, 3 county and 3 district hospitals) in Sweden. The heads of the cardiology departments were contacted and asked to give permission for cardiac rehabilitation nurses to participate in the study. All 10 Heads gave their approval and forwarded the names of the CRNs who met the inclusion criteria.

2.2. Participants

The inclusion criteria were CRNs, who were actively working with comprehensive CRPs in which physical training, education, risk factor modification, medical checks-ups, pharmacological treatment, psychological support and counseling, as well as vocational rehabilitation were included. The CRNs also had to be members of a multidisciplinary cardiac rehabilitation team (e.g. cardiologist, nurse, and physiotherapist) and fully understand, read and speak Swedish. Twenty-one CRNs were informed and asked to participate by the main author (IW), only one declined; due to time constraints. All CRNs were females and ages ranged between 28 and 65. The time having worked in cardiac care was between 4 and 25 years and between 2 and 23 years within cardiac rehabilitation.

2.3. Data Collection

Data was collected through interviews conducted and recorded by the main author (IW). The main author phoned the CRNs and asked them to choose a place and time for the interview. All interviews were conducted at the informants’ work place. Four pilot interviews were conducted, which then were included in the analysis. The interviews started with an open main question: “What do you think about women’s recovery after a first myocardial infarction?” In order to reach depth in data follow up questions such as “What do you think when you say…?” and “Can you explain more about…?” were asked. The interviews lasted between 35 and 75 minutes. All the interviews were transcribed verbatim.

2.4. Data Analysis

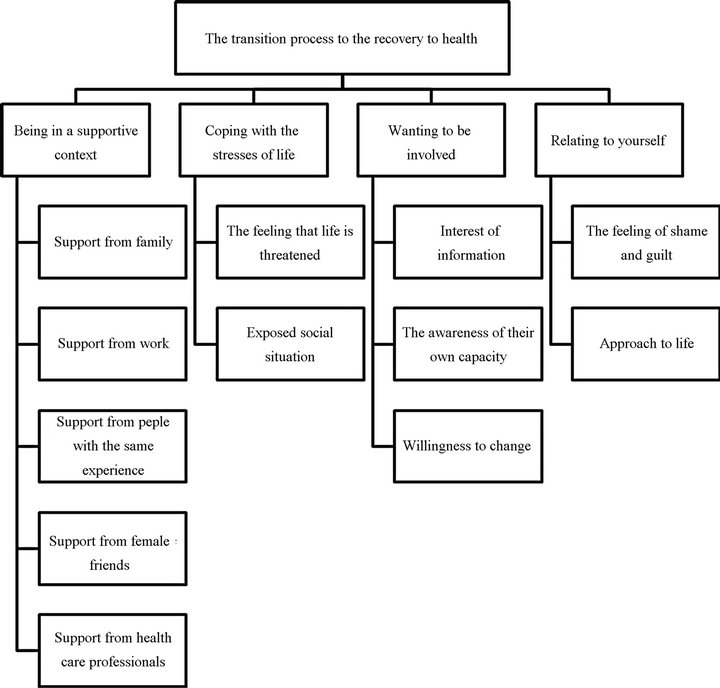

Data was processed by the main author, in collaboration with the co-authors, using qualitative content analysis which consists of several analysis steps as described by Graneheim and Lundman [32]. The interviews were read through several times to become familiar with the text. Meaning units that were related to the aim of the study were placed in an analytical matrix. These meaning units were then condensed without losing the core of the content. In the next analysis step, the condensed meaning units were abbreviated to codes. These codes were compared, based on differences and similarities, and 12 subcategories were created forming 4 categories at a manifest level. Based on the content of these categories an overall theme emerged, which expressed the latent meaning of the content (Figure 1) [32].

2.5. Ethical Consideration

The ethical principles of the study were according to the requirements of the world medical association declaration of Helsinki [33] and the heads of the cardiology departments have approved the study. After the participants were fully informed, both verbally and in writing, of the aim of the study and the voluntary nature of participation, as well as the possibility of withdrawing, an informed consent was obtained.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Being in a Supportive Context

This category described that CRNs’ experiences that women’s opportunities to receiving support could either help or hinder the women’s recovery process. A major requirement for recovery was access to a good social network, where family, relatives, peers and friends had a supportive attitude, as well as support from health care and workplace.

The newly found situation involved not only the woman, but the whole family so therefore it was important how the support from the family was. The women, who had a functioning family life, where they felt safe and harmonious, generally recovered more easily. “The family, home, and how they have it at home, has an impact” ... (n3). It was important that the female’s partner was actively involved in the recovery process, as well as a well-functioning dialogue between family members. Interaction with children and grandchildren could distract the women from having negative thoughts. In cases where the children helped with practical things also created better possibilities for the women to recover. Likewise, when the family took into account, that it is not always the woman, the mother, who has to do everything in the

Figure 1. Illustration of the transition process to the recovery to health through theme, categories and subcategories.

family, this influenced the woman’s recovery in a positive way. However, the women’s recovery was negatively influenced when they lacked support from their families as well as unsympathetic partners and family members who, neither understood, nor took into account the new situation. Many women, I’ve heard this many times by women who say that “Yes, but you were in hospital for four days, now you’re all right. What is wrong with you”? (n1). The families did not take time to listen, but instead, perceived the women as somewhat whining. Furthermore, they wanted everything to work in the home as before and desired the traditional female role. The women had more difficulty to implement the necessary recommended lifestyle changes. However, women became passive, especially in cases where women were overprotected by their family and were not allowed to do any daily work or exercise at all; which did not help the recovery process.

Support from work where the women were given possibilities to participate in various rehabilitation groups during working hours affected their recovery positively. “…, it all depends on... what they are working with. Large companies often let them go, but small, private companies, where they often do not have many employees, therefore more dependent upon staff, where it is a little harder to take one afternoon off a week ...” (n3). The women’s recovery was facilitated when employers arranged more regular working hours and less planned overtime.

Regarding support from people with the same experience, it emerged that women usually experienced great gains when they met others in the same situation in the rehabilitation groups. “I’ve heard women say that really, to meet other women in the same situation is better than the entire health care! So it is of great importance” (n2). Friendships developed, for example at the exercise training during the months the group members met, which led the women to continue to meet and exercise together, share experiences and support each other, after the initial group training period had come to an end. The women emphasized the importance of meeting people who understood their situation which was perceived as an additional support, something that made them realize that they were not alone.

Concerning support from female friends, it became evident that women willingly spoke more to their friends than to their partners when it came to their innermost thoughts and their situation. “And then women have more than men, good friends who support each other, I am sure we can say ...” (n13). Since emotional support was important for the women with regard to recovery, it was important that there were female friends around when needed.

Support from healthcare professionals deals with counseling and support during the women’s recovery process. This involved: having an experienced nurse to turn to, having confidence and assurance in the nurse, as well as, continuity of care. The CRNs, as well as the team’s approach, were also important in regard to the women’s recovery. “The fact that we also provide support, that they can call us and get adequate and accurate answers to their, all the questions they have… that we have the expertise, that we have faith to give a correct answer. Both in medical terms, and to be able to encourage and help them when attempting to quit smoking...” (n11). The women’s recovery was also influenced when the nurses managed to get the women: motivated to exercise, to be aware of both their risk and health factors which resulted in the women feeling better and stronger after visiting the nurse. Even physical training, under supervision, gave the women security which stimulated them to do more physical exercise. Likewise, medical assistance was of great importance. Their recovery was also affected by them knowing that they were prescribed the appropriate medication, and that the physician spoke about what they should or should not do.

3.2. Coping with the Stresses of Life

This category described the CRNs’ experiences of that the women’s recovery was influenced by their ability to cope with the stresses of life such as: concerns for themselves and returning to work, the fear of dying and not doing enough for the family. Furthermore, the CRNs described that women’s recovery was affected by whether the woman had: a socially vulnerable situation with high demands, lack of finances, additional diseases and intensive treatments, as well as, whether they had experienced previous severe life events.

Regarding the feeling that life is threatened, it became clear that the women’s recovery was affected by the fear of dying and of being inadequate. The women admitted to keeping a closer watch on their own physical and mental symptoms which contributed to them noticing everything that felt different within the body compared with before. “There are ... many who talk about ... that they have, indeed a fear that it will happen again.” (n3). These thoughts came in the evening when it was quiet; therefore, sleeping habits could be adversely affected. Not infrequently, women had difficulty formulating their concerns into words and they avoided any discussions that they had been close to death. Instead, they had a need to dwell upon what had happened, to digest their new situation, in order to be able go forward in the recovery process. The women also had concerns about sexuality, and there were women who did not dare to have sexual intercourse as they were afraid that something could happen to the heart. The concern could also be about the fear of being sexually inactive and that inactivity and loss of desire would be permanent. Furthermore, it was also found that women were concerned about how the family would manage, now that they had suffered from ill health and could not cope with everyday tasks in the same way as before. “But it also seems like there is much concern for ... for the family ... usually the first ... you could say the first three or four months” (n1). Even the thought of returning to work concerned the women. Work could be experienced as difficult, both physically and mentally. “Obstacles to recovery, that is, I often have the feeling, those who are working, they will have the same amount of stress, they often say, as before. What will happen?” (n7). Many times, the women wished to have a longer period of sick leave in order to have time to their recovery.

Coping with stresses in life was affected by whether the women had an exposed social situation. The women’s recovery was influenced by earlier completed traumatic life events, such as: abuse, divorce, serious illness within the family and death. “The fact that women have, quite often, experienced some rather severe life events which surface again when you have a heart attack. Yes, something from the past that you think you have got over, but it still pops up in your head, in connection with a heart attack. It can be anxiety, anguish; therefore, it becomes a tougher time before they recover.” (n14). Furthermore, it was also found that there were women who stated that they already had a reduced work capacity, due to illness, resulting in a partial or full disability pension. This could be an additional burden that affected their recovery after an MI. Previous mental illness, depression and the onset of depression during the recovery phase also contributed to the fact that some women often declined to participate in CRP. “If you have experienced a breakdown in the past or suffered from depression; you are, of course, more vulnerable” (n14). Another factor that affected the women’s recovery was which stage in life the women were in. The older women accepted, more easily, their illness, which they associated with age. They were not as easily affected by stress and often put more time and effort on lifestyle changes than younger women. Elderly women had more time and used it well, walking, as well as planning the purchase and cooking of healthy nutriatious food; which made the recovery easier. Younger women who worked and had young children did not have time to think and act this way.

Moreover, women who have had Coronary Artery Bypass Surgery [CABG] had more often a longer and tougher recovery period than women who underwent Percutaneous Coronary Intervention (PCI) or any other intervention, in connection to their MI. This was the reason why they felt fatigued and could not face up to current situations in the same way as the women who had undergone PCI. Even certain drugs and their side effects affect the women’s daily life in a negative manner.

Furthermore, the women’s social situation with poor finances and a lack of time, regardless of age, contributed to the fact that they did not have the opportunity to focus on themselves and their own situation. This is a reason why the women did not participate in CRP, which also affect their recovery process. “You can be on low income, perhaps a single parent, you are struggling financially and you become sick too. Yes, things like that.” (n16). The women, intellectually, understood that CRP group meetings would be important to their recovery, but regardless of how hard they tried to plan their lives, there was a lack of time and money.

3.3. Wanting to Be Involved

This category described the CRNs’ experiences of how the women’s recovery was influenced by their interest and desire to know how they, themselves, affect their new life situation and make sure that they prioritized themselves.

The women’s recovery was affected by their own interest of information with regard to the desire to know of risk and health factors, and understanding what exactly an MI was and what they should think about in the future. “The experience is that women are more interested in finding out, getting knowledge than men. They have more questions and concerns and it feels like they care more” (n4). They wanted to learn about the importance of diet and exercise in order to recover, how their prescribed drugs worked and about the body’s normal physical and mental reactions. When the women had many questions concerning their new life situation, the new-found knowledge gave them a certain security. CRPs, which lasted for four to five weeks, gave them the opportunity to take in the knowledge gradually. The more information the women took in, the higher was their chance to recover.

Through the women’s involvement in their care, the awareness of their own capacity was strengthened and led them not to see themselves only as “sick persons”. They realized that they should be in charge of their own lives; therefore, changing their present situation into something better, which also led to a part of their recovery, “That you gain an insight into your illness and that you can accept this and get an understanding of what it implies” (n12). Likewise, when the women did group physical training, they became aware of what they managed without getting chest pain. This meant that they became less worried about straining themselves physically when they were on their own.

Regarding willingness to change, it was described that many women were interested in getting help and support in order to change their lifestyles, and therefore, prioritizing participation in various CRPs. The women, who went to CRPs, were motivated to learn new things regarding: diet, exercise, medications, and just what research revealed concerning health factors; which helped in the recovery. “Women change their diet, exercise habits and weight” (n15). Women were particularly keen to change their diet. Those, who found it easy to get started with physical training, recovered more quickly. Women, who relatively quickly went back to work, possibly only part-time, and those who tried to change their work situation to prevent negative stress, generally recovered more quickly than women who continued to be on sickleave. To effectively implement the changes in life was easier for the women who lived a somewhat carefree life when they fell ill and had a supportive family.

3.4. Relating to Yourself

This category highlighted the CRNs’ experiences of that women’s recovery was influenced by the way they related to themselves.

Regarding the feeling of shame and guilt, it emerged that there were women who expressed embarrassment over, both their smoking habits, and their overweight. They expressed an intention to stop smoking but they had relapsed and returned to their comforting smoking habits, which created a feeling of guilt. Not infrequently, they ended their participation in the CRPs which could affect their recovery adversely. Women also felt ashamed and guilty that they had fallen ill in the first place. “Women make themselves feel guilty ... I should not be doing this ... How did this happen? I should have foreseen” (n19). There were also women who felt guilty that their recovery took such a long time. These women needed to receive help to think through their life and work situation before they could continue their recovery.

The women’s approach to life could affect their recovery. The women who had a positive attitude experienced, in general, less anxiety than those with a pessimistic attitude. “It is individual how you recover. It depends on what kind of personality you have ...” (n13). Even women, who had to have total control over their home situation, and thought that everything would work as it always had done, otherwise their world around them would collapse, usually had difficulty in recovering. Having to be perfect was a common feature of these women. These women did not allow themselves to be sick and prioritized others before themselves; therefore, hampering their own recovery. “When it comes to women so maybe … they have to fix it by themselves … They must be the strong one in the family in some way, they do not have time to be sick and it could be the career. Such things influence” (n12). Furthermore, there were women who had difficulty accepting their illness. They had difficulty in seeing themselves as sick and did not understand the onset of the illness; despite the many risk factors. The women with a more positive outlook on life changed their lifestyles when they now had got a second chance. They expressed that they had been given a new lease of life; thanks to: a deeper understanding of their first MI, an altered diet, new exercise habits, and their letting go of certain everyday demands. However, there were women who reported finding it challenging to relax their demands on themselves regarding the performance of everyday tasks.

4. DISCUSSION

The CRNs experienced that women’s recovery after an MI was influenced by factors related both to their surroundings as well as by their own factors. The underlying meaning of the women’s recovery can be described as: the transition process to the recovery to health. This transition process agrees with Schumacher and Meleis [34] interpretation of the concept “transition” as a profound inner process that influences the whole person and implies a new appreciation of life. The transition process to the recovery to health of the women, according to the CRNs’ experiences in this study, depended on the women’s ability to cope with the new life situation, as well as if they wanted to be involved in their care and were interested in increasing their knowledge of their illness and their treatment options. The transition process also depended on whether they had a positive approach to life and if the women had a good supportive context. This is in line with Meleis et al. [35] who describe that transition requires that a person has the ability to absorb new knowledge, change their behavior and thus the definition of self. It is important that CRNs are aware, that transition after an MI is a personal journey; so therefore, nursing should be person-centered in order to promote the women’s unique recovery. Thus, CRNs should not put a time limit for the transition period because there are critical points and events which can affect the transition process [35]. An essential requirement for recovery for the women was access to support from their surroundings such as family, relatives, friends, and workplace as well as from other women with the same experiences. The women’s recovery was, however, influenced negatively when they lacked support from their families. This indicates that it is important that families receive support from health care professionals in order to have the strength to give support to the ill person, which is confirmed by Ziegert [36]. The results even show that the women wanted counseling and support from the health care professionals during their recovery process. This is supported by Meleis et al. [35] who describes that confirmation, counseling and feedback are presumptions in order to get a successful transition to health. Earlier research has shown that the length of time of recovery for women, who received support from health care professionals throughout CRP, was shorter than for women who did not receive this support [37]. Therefore, it is essential that the CRNs support the women both in their clinical and personal recovery [14,16,17,19] and give the women the opportunity to an individually designed secondary prevention. Support from their surroundings, gives the women an opportunity to share their thoughts and gives people an understanding for the women’s new situation. Women also need to share their thoughts with people with the same experience. The importance of peer support for women is well-known in research [38,39] where women describe that peer support gives them valuable experiences when they have the opportunity to share their feelings with other women. This indicates that peer support is an essential intervention in order to promote the women’s recovery. Thus, the CRNs are faced with the challenge of how to best organize and integrate peer support interventions into the usual health care.

The results show that the women’s recovery was influenced by the fear of dying and the feeling of not being adequate, which is confirmed in earlier studies [12,18,19, 22,40]. Fears of dying in our results show that the women felt anxiety and were afraid of suffering another MI. These findings correspond to earlier studies that indicate that women with MI can experience this worry and anxiety; especially during the first four months [12, 19,22,40,41]. Therefore, it is important that CRNs meet the women’s needs and discuss their concerns so that the anxiety does not become pathological and negatively interfere their ability to recovery for a longer time. Furthermore, sexual concerns seem to induce worry and anxiety for the women. In Arenhall et al.’s study [42] male partners experienced that their partner was more fragile after an MI, which could result in male partners becoming more hesitant when it came to sexual intimacy. Research has shown that knowledge regarding sexuality after an MI is poor for both male and female patients. In fact, females have even lesser knowledge in comparison to males [43]. CRNs’ knowledge and counseling, related to sexual issues, can play a key role: both in a supportive manner as well as impeding women to feel safe to talk about sexual concerns during their recovery process. Therefore, CRNs need both knowledge and specific education in order to provide counseling and support when addressing sexual issues [44-46].

Other factors that affected the women’s ability to cope with their new life situation were whether the women had a socially vulnerable situation i.e. poor finances and lack of time. These factors, regardless of the women’s age, contributed to the fact that they did not have the opportunity to focus on themselves and their own situation. This could be one of the reasons why the women do not participate in CRP, which is also underlined in others studies [12,22]. Research has also shown that acute cardiac care, where both male and female patients from lower income groups did not undergo intervention as often as high earners; is a fact which affected their recovery [47]. Therefore, nurses must attach importance to being aware of socio-economic disparities when it comes to having access to both acute care and secondary prevention [48]. To address the barriers related to the access to secondary prevention, due to e.g. poor finances and place of residence, new innovative methods such as mHealth and eHealth need to be developed [49,50]. As peer support seemed to be important for women’s recovery [38,39], support by telephone or internet from peers may provide sufficient support for women who for some reason are isolated and not able to attend CRPs at hospitals [51]. As research even has shown that eHealth has been suggested as a potential solution for health care professionals to connect to patients who not are able to participate to CRPs at hospitals, it is important that the nurses develop new innovative digital methods regarding eHealth for patients [52]. In addition, the development of digital CRPs present particular challenges as these services should be accessible to all patients in order to promote a more equitable care. This is important as low socio-economic status has been shown to be associated with increased heart disease incidence and mortality [24, 53].

The results show that women’s recovery was influenced by their interest and desire of knowledge of how they, themselves, could affect their new life situation and how they prioritized themselves. If the women learned that they should not see themselves as ill and that they could take control of their lives by changing their situation into something better; the recovery process was affected positively. The individual recovery process is about learning to live with the changes that an MI entails [18,19,34], as well as a high degree of involvement in, and knowledge of, your own care. All this promotes a successful personal transition process [34,35]. Research shows that if patients are involved in their own recovery process it leads to better results of the treatment, and to a higher degree of satisfaction regarding the care [54]. It also shows how important it is that CRPs strive to care for the relationship with the patient, as research has found that the quality of the nurse-patient relationship is of great importance for the patient’s involvement [55]. Many patients have expressed the wish to have more involvement in the MI-care; certainly more than they are offered at present [56]. Therefore, this requires that the nurses encourage the patient to be involved in her own process of recovery as well as nurses are aware of people’s different needs for tailored information to gather knowledge [57,58].

Furthermore, the results show that CRNs experienced that the women expressed embarrassment and feelings of guilt over their lifestyle and that they had fallen ill. They expressed an intention to stop smoking but many relapsed into their comforting smoking habits, often ending their participation in the CRPs and then were left with a feeling of guilt that their recovery had taken such a long time. The result of guilt due to illness also corresponds to earlier research [40]. It is important that CRNs acknowledge the women’s attempt to change their life situation and not to blame them if they do not succeed. If the women feel ashamed of their lifestyle and that they suffered a first MI, it will not lead to empowerment, but to the opposite. Results even show that women, who have to have total control over their home situation, usually experienced difficulty in recovering. The pressure of being perfect was a common feature of these women who did not allow themselves to be sick and put themselves last therefore, hampering their recovery. Research describes that it is common that women, during their recovery process, still continue to be responsible for much of the work at home; including keeping in contact with relatives and friends [28]. Schumacher and Meleis [34] describe that persons who can handle their new life situation regarding surroundings and who can manage the demands of the new situation promotes their transition more positively than those who cannot. Therefore, this suggests that the women’s difficulties in letting go of the household chores to their partner does not depend on their partner’s incompetence but because women want to keep their matriarchal gender role [28,29]. Worth noting is that CRNs, in this study, did not highlight women’s stress as a factor affecting women’s recovery, since earlier research shows that stress is a major factor for MI [12,38].

Methodological Consideration

In order to increase the variation in the material a quailtative content analysis was chosen [32]. The purposive selection of cardiac rehabilitation nurses, who have different experiences (age, different working experience in cardiac care, different hospitals) of female patients’ recovery, increased the potential for achieving rich variation of the phenomenon under study, which strengthen the credibility but among the respondents there were no male CRN and this could limit the credibility of the study. Qualitative interviews with the same main question were deemed suitable for catch the aim. The follow-up questions allowed the CRNs to reflect and expand their views on the factors that influence female patients’ recovery after their first MI. Another aspect of credibility in the present study was seeking agreement between the authors, how well the codes, categories and the theme covered the data. The authors worked both individually and together during the analysis process until a consensus was reached. Likewise, if the chosen quotations reflect the content of each category, it offers the reader an opportunity to determine the credibility of the study [32]. To establish dependability frequent discussions and a continuous dialogue among the authors took place so that our standpoints concerning differences and similarities of content were consistent over time [32]. The results could be of interest from the transferability perspective, as the CRNs’ experiences can be useful in cardiac clinical nursing as a contribution to the ongoing discussion and improvement of nursing care connected with female patients’ recovery after an MI [32].

5. CONCLUSION AND IMPLICATION

Cardiac rehabilitation nurses experienced that women’s recovery after an MI was influenced by factors that were both related to their surroundings as well as by their own individual factors. The underlying meaning of women’s recovery is characterized as the transition process for a recovery to health. This transition process is influenced by the women’s ability to cope with the new life situation, if they wanted to be involved in their care, if they had a positive approach to life, as well as, if the women had a good supportive context. Our findings suggest that a focus on person-centered nursing would be beneficial in order to promote the every woman’s personal and unique recovery after an MI. The present study also emphasizes the importance of how new innovative digital methods could be developed in order to face the barriers related to the access to CRP and increasing its accessibility, in order to meet different patients’ needs. These findings also raise questions about the women’s own attitudes and experiences of how their recovery is promoted in the MI care. Finally, the CRNs’ experiences of factors influencing male patients’ recovery after their first MI should be important to investigate.

REFERENCES

- Gaziano, T.A., Bitton, A., Anand, S., Abrahams-Gessel, S. and Murphy, A. (2010) Growing epidemic of coronary heart disease in lowand middle-income countries. Current Problems in Cardiology, 35, 72-115. doi:10.1016/j.cpcardiol.2009.10.002

- Wenger, N.K. (2003) Coronary heart disease: The female heart is vulnerable. Progress in Cardiovascular Diseases, 46, 199-229. doi:10.1016/j.pcad.2003.08.003

- The National Board of Health and Welfare (2008) The National Board of Health and Welfare guidelines for cardiac care. Socialstyrelsen, Stockholm.

- Johansson Sundler, A. (2008) Mitt hjärta, mitt liv: Kvinnors osäkra resa mot hälsa efter en hjärtinfarkt. My heart, my life: Women’s uncertain health journey following a myocardial infarction. Växjö University Press, Växjö.

- Perk, J., Guy De Backer, G., Gohlke, H., Graham, I., Zeljko Reiner, Z., Verschuren, M., et al. (2012) European guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice (version 2012). European Heart Journal, 33, 1-77.

- SWEDEHEART (2012) SWEDEHEART 2011 annual report. Matador Kommunikation, Uppsala.

- World Health Organization (WHO) (2005) Preventing chronic diseases: A vital investment: WHO global report. World Health Organization, Geneva.

- World Health Organization (WHO) (1993) Needs and action priorities in cardiac rehabilitation and secondary prevention in patients with coronary heart disease. WHO Regional Office for Europe, Geneva.

- Piepoli, MF., Corrà, U., Benzer, W., Bjarnason-Wehrens, B., Dendale, P., Gaita D., et al. (2010) Secondary prevention through cardiac rehabilitation: from knowledge to implementation. A position paper from the cardiac rehabilitation section of the European association of cardiovascular prevention and rehabilitation. Cardiac rehabilitation section of the European association of cardiovascular prevention and rehabilitation. European Journal of Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation, 17, 1-17. doi:10.1097/HJR.0b013e3283313592

- Jackson, L., Leclerc, J., Erskine, Y. and Linden, W. (2005) Getting the most out of cardiac rehabilitation: A review of referral and adherence predictors. Heart, 91, 10-14. doi:10.1136/hrt.2004.045559

- De Feo, S., Tramarin, R., Ambrosetti, M., Riccio, C., Temporelli, P.L., Favretto, G., et al. (2012) Gender differences in cardiac rehabilitation programs from the Italian survey on cardiac rehabilitation (ISYDE-2008). International Journal of Cardiology, 160, 133-139. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2011.04.011

- Sjöström-Strand, A., Ivarsson, B. and Sjöberg, T. (2011) Women’s experience of a myocardial infarction: 5 years later. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 25, 459- 466. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6712.2010.00849.x

- Jackson, J.C., Hart, R.P., Gordon, S.M., Shintani, A., Truman, B., May, L., et al. (2003) Six-month neuropsychological outcome of medical intensive care unit patients. Critical Care Medicine, 31, 1226-1234. doi:10.1097/01.CCM.0000059996.30263.94

- Slade, M. and Hayward M. (2007) Recovery, psychosis and psychiatry: Research is better than rhetoric. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 116, 81-83. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.2007.01047.x

- Mancini, M.A., Hardiman, E.R. and Lawson, H.A. (2005) Making sense of it all: Consumer providers’ theories about factors facilitating and impeding recovery from psychiatric disabilities. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 29, 48-55. doi:10.2975/29.2005.48.55

- Anthony, W.A. (1993) Recovery from mental illness: The guiding vision of the mental health service system in the 1990s. Innovations & Research, 2, 17-24.

- Deegan, P. (1996) Recovery as a journey of the heart. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 19, 91-97.

- Tod, A. (2008) Exploring the meaning of recovery following myocardial infarction. Nursing Standard, 23, 35- 42.

- Tobin, B. (2000) Getting back to normal: Women’s recovery after a myocardial infarction. Canadian Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing, 11, 11-19.

- Fridlund, B. (2002) The role of the nurse in cardiac rehabilitations programmes. European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing, 1, 15-18. doi:10.1016/S1474-5151(01)00017-2

- Hedback, B., Perk, J. and Wodlin, P. (1993) Long-term reduction of cardiac mortality after myocardial infarction: 10-year results of a comprehensive rehabilitation programme. European Heart Journal, 14, 831-835. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/14.6.831

- Kerr, E.E. and Fothergill-Bourbonnais, F. (2002) The recovery mosaic: Older women’s lived experiences after a myocardial infarction. Heart & Lung, 31, 355-367. doi:10.1067/mhl.2002.127939

- Rankin, S.H. (2002) Women recovering from acute myocardial infarction: Psychosocial and physical functioning outcomes for 12 months after acute myocardial infarction. Heart & Lung, 31, 399-410. doi:10.1067/mhl.2002.129447

- McSweeney, J.C. and Coon, S. (2004) Women’s inhibittors and facilitators associated with making behavioral changes after myocardial infarction. Medical-Surgical Nursing, 13, 49-56.

- Svedlund, M. and Danielson, E. (2004) Myocardial infarction: Narrations by afflicted women and their partners of lived experiences in daily life following an acute myocardial infarction. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 13, 438- 446. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2702.2004.00915.x

- Worrall-Carter, L., Jones, T. and Driscoll, A. (2005) The experiences and adjustments of women following their first acute myocardial infarction. Contemporary nurse. A Journal for the Australian Nursing Profession, 19, 211- 221.

- Day, W. and Batten, L. (2006) Cardiac rehabilitation for women: One size does not fit all. Australian Journal of Advanced Nursing, 24, 21-26.

- Hildingh, C., Fridlund, B. and Lidell, E. (2007) Women’s experiences of recovery after myocardial infarction: A meta-synthesis. Heart & Lung, 36, 410-417.

- Eriksson, M., Asplund, K. and Svedlund, M. (2009) Patients’ and their partners’ experiences of returning home after hospital discharge following acute myocardial infarction. Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing, 8, 267-273. doi:10.1016/j.ejcnurse.2009.03.003

- Stevens, S. and Thomas, S.P. (2012) Recovery of midlife women from myocardial infarction. Health Care for Women International Health, 33, 1096-1113. doi:10.1080/07399332.2012.684815

- Downe-Wamboldt, B. (1992) Content analysis: Method, applications, and issues. Health Care for Women International, 2, 313-321. doi:10.1080/07399339209516006

- Graneheim, U.H. and Lundman, B. (2004) Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: Concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Education Today, 24, 105-112. doi:10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001

- World Medical Association (2008) Declaration of Helsinki—Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. The World Medical Association (WMA), Seoul.

- Schumacher, K.L. and Meleis, A.I. (1994) Transitions: A central concept in nursing. The Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 26, 119-127. doi:10.1111/j.1547-5069.1994.tb00929.x

- Meleis, A.I., Sawyer, L.M., Im, E., Messias, D.K. and Shumacher, K. (2000) Experiencing transitions: An emerging middle-range theory. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 23, 12-28.

- Ziegert, K. (2011) Maintaining families’ well-being in everyday life. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being, 6.

- Wieslander, I., Baigi, A., Turesson, C. and Fridlund, B. (2005) Women’s social support and social network after their first myocardial infarction: A 4-year follow-up with focus on cardiac rehabilitation. European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing, 4, 278-285. doi:10.1016/j.ejcnurse.2005.06.004

- Sjöström-Strand, A. and Fridlund, B. (2006) Women’s descriptions of coping with stress at the time of and after a myocardial infarction: A phenomenographic analysis. Canadian Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing, 16, 5-12.

- White, J., Hunter, M. and Holttum, S. (2007) How do women experience myocardial infarction? A qualitative exploration of illness perceptions, adjustment and coping. Psychology Health & Medicine, 12, 278-288. doi:10.1080/13548500600971288

- Svedlund, M., Danielson, E. and Norberg, A. (2001) Women’s narratives during the acute phase of their myocardial infarction. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 35, 197- 205. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2648.2001.01837.x

- Alsén, P., Brink, E., Persson, L.O., Brändström, Y. and Karlson, B.W. (2010) Illness perceptions after myocardial infarction: Relations to fatigue, emotional distress, and health-related quality of life. Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing, 25, E1-E10.

- Arenhall, E., Kristofferzon, M.L., Fridlund, B., Malm, D. and Nilsson, U. (2011) The male partners’ experiences of the intimate relationships after a first myocardial infarction. European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing, 10, 108-114. doi:10.1016/j.ejcnurse.2010.05.003

- Nilsson, U.G., Svedberg, P., Fridlund, B., Alm-Roijer, C., Thylén I. and SAMMI-Study Group (2012) Sex knowledge in males and females recovering from a myocardial infarction: A brief communication. Clinical Nursing Research, 21, 486-494. doi:10.1177/1054773812437241

- Jaarsma, T., Strömberg, A., Fridlund, B., De Geest, S., Mårtensson, J., Moons, P., et al. (2010) Sexual counselling of cardiac patients: Nurses’ perception of practice, responsibility and confidence. European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing, 9, 24-29. doi:10.1016/j.ejcnurse.2009.11.003

- Jaarsma, T., Steinke, E.E. and Gianotten, W.L. (2010) Sexual problems in cardiac patients: How to assess, when to refer. Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing, 25, 159-164.

- Steinke, E.E. (2010) Sexual dysfunction in women with cardiovascular disease: What do we know? Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing, 25, 151-158.

- Rosvall, M., Chaix, B., Lynch, J., Lindström, M. and Merlo, J. (2008) The association between socioeconomic position, use of revascularization procedures and fiveyear survival after recovery from acute myocardial infarction. BMC Public Health, 1, 44. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-8-44

- Haglund, B., Köster, M., Nilsson, T. and Rosén, M. (2004) Inequality in access to coronary revascularization in Sweden. Scandinavian Cardiovascular Journal, 38, 334-339. doi:10.1080/14017430410021516

- Varnfield, M., Karunanithi, M.K., Särelä, A., Garcia, E., Fairfull, A., Oldenburg, B.F., et al. (2011) Uptake of a technology-assisted home-care cardiac rehabilitation program. The Medical Journal of Australia, 194, S15-S19.

- Pfaeffli, L., Maddison, R., Whittaker, R., Stewart, R., Kerr, A., Jiang, Y., et al. (2012) A Health cardiac rehabilitation exercise intervention: findings from content development studies. BMC Cardiovascular Disorders, 12, 36. doi:10.1186/1471-2261-12-36

- Parry, M.J., Watt-Watson, J., Hodnett, E., Tranmer, J., Dennis, C.L. and Brooks, D. (2009) Cardiac Home Education and Support Trial (CHEST): A pilot study. Canadian Journal of Cardiology, 25, 393-398. doi:10.1016/S0828-282X(09)70531-8

- Vandelanotte, C., Dwyer, T., Van Itallie, A., Hanley, C. and Mummery, W.K. (2010) The development of an internet-based outpatient cardiac rehabilitation intervenetion: A Delphi study. BMC Cardiovascular Disorders, 10, 27. doi:10.1186/1471-2261-10-27

- Pollitt, R.A., Rose, K.M. and Kaufman, J.S. (2005) Evaluating the evidence for models of life course socioeconomic factors and cardiovascular outcomes: A systematic review. BMC Public Health, 5, 7-13.

- Williams, G.C., Freedman, Z.R. and Deci, E.L. (1998) Supporting autonomy to motivate patients with diabetes for glucose control. Diabetes Care, 21, 1644-1651. doi:10.2337/diacare.21.10.1644

- Sahlsten, M.J., Larsson, I.E., Sjöström, B., Lindencrona, C.S. and Plos, K.A. (2007) Patient participation in nursing care: Towards a concept clarification from a nurse perspective. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 16, 630-637. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2702.2006.01660.x

- Arnetz, J.E. and Arnetz, B.B. (2009) Gender differences in patient perceptions of involvement in myocardial infarction care. European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing, 8, 174-181. doi:10.1016/j.ejcnurse.2008.11.002

- Young, L.E. and Murray, J. (2011) Patients’ perception of their experience of primary percutaneous intervention for ST segment elevation myocardial infarction. Canadian Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing, 21, 20-30.

- Sherrod, M., McIntire Sherrod, N., Tate Spitzer, M. and Cheek, D. (2012) Prevention of heart disease in women: Considerable challenges remain. Open Journal of Nursing, 2, 176-180. doi:10.4236/ojn.2012.23027

NOTES

*This study was supported by research grants from The Swedish HeartLung Foundation and The Swedish Heart and Lung Association.

#Corresponding author.