Open Journal of Psychiatry

Vol.4 No.1(2014), Article ID:42276,12 pages DOI:10.4236/ojpsych.2014.41012

Perceptions of treatment among offenders with mental health problems and problematic substance use: The possible relevance of psychopathic personality traits

1Department of Clinical Neuroscience, Division of Forensic Psychiatry, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden

2Department of Psychology, Stockholm University, Stockholm, Sweden

Email: *Natalie.Durbeej@ki.se

Copyright © 2014 Natalie Durbeej et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. In accordance of the Creative Commons Attribution License all Copyrights © 2014 are reserved for SCIRP and the owner of the intellectual property Natalie Durbeej et al. All Copyright © 2014 are guarded by law and by SCIRP as a guardian.

Received 23 December 2013; revised 15 January 2014; accepted 22 January 2014

KEYWORDS

Substance Abuse; Treatment; Recidivism; Psychopathy; Offenders

ABSTRACT

Substance abuse is related to re-offending, and substance abuse treatment may be effective in reducing criminal recidivism. Psychopathy, however, another factor that strongly correlates with re-offending, may be negatively associated with treatment utilization. This qualitative study explored perceptions of substance abuse treatment among offenders with mental health problems, problematic substance use, and various degrees of psychopathic personality traits. An Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA) revealed that some treatment perceptions may vary with degree of psychopathic traits. For instance, participants with low and high degrees of psychopathic personality traits had different views on treatment requirements imposed upon them. Many treatment perceptions were also similar between the two participant groups. Thus, treatment perceptions may not be explained by degree of psychopathic personality traits alone, but the presence of some particular psychopathic traits may be relevant in explaining certain treatment perceptions. The results highlight the complex relationship between the individual and the treatment system, and may give input to future studies on rehabilitation of offenders with multiple treatment needs.

1. INTRODUCTION

The associations between mental health problems, substance abuse and criminality have been firmly established in research [1]. Co-morbidity of substance abuse and mental health problems is common among offenders [2,3] and has been identified as an important risk factor for criminal behavior [1,4]. In order to reduce the risk of criminal recidivism, mental health problems as well as substance abuse should be taken into account [5].

In addition to substance abuse and mental health problems, psychopathy has been identified as an important predictor of criminal behavior, particularly violence [6]. There has been a long-standing debate on the definition of the psychopathy-concept. The Canadian psychologist Robert Hare suggested that psychopathy should be considered as a cluster of interpersonal and affective personality traits as well as antisocial behaviors such as grandiosity, callousness, lack of empathy, impulsivity and criminal versatility [7]. Other researchers have proposed that the concept merely involves interpersonal and affective traits, and that antisocial behavior is a consequence, rather than an inherent part of the construct [8]. Although there are different opinions on this topic, the definition suggested by Robert Hare has been used frequently in research during the past decades [9].

Psychopathy or psychopathic personality traits may be prevalent among offenders with mental health problems. As an example, one study suggested a psychopathy prevalence rate of 23% among offenders with mental disorder [10]. Psychopathy is also an important predictor of re-offending among offenders with mental health problems as well as in other populations [6,11,12]. As a consequence, researchers and clinicians have highlighted the need to elaborate treatment strategies for crime prevention targeting offenders with psychopathic personality traits [13].

1.1. Treatment Utilization and Criminal Recidivism among Offenders with Mental Health Problems and Problematic Substance Use

Substance abuse is common among offenders with mental health problems [3,14]. Offenders with mental health problems and problematic substance use1 have multiple treatment needs [14,15]. After release from prison or forensic psychiatric care, many end up homeless and unemployed, and have a high risk of recidivating into criminal behavior. Thus, this population may require support regarding employment and housing as well as interventions that target mental health problems, problematic substance use, and criminal behavior. The need to develop strategies for treatment, support, and crime prevention particularly targeting these individuals has been repeatedly highlighted [14-16].

Research on treatment utilization among offenders with mental health and problematic substance use is rather scarce. However, results from a Swedish study— Mental disorder, Substance Abuse and Crime (MSAC)— indicated that this population utilized heavy amounts of outpatient substance abuse treatment and psychiatric treatment, but with great variation [17]. Some treatment utilization patterns suggested were discontinuous with disruptive stays in treatment, whereas others were stable over time. An earlier study of the same population concluded that more than six weeks in planned outpatient treatment focusing problematic substance use was associated with a reduced risk of re-offending [18]. In addition, international research has highlighted the benefit of other treatment programs, e.g. therapeutic communities, methadone maintenance programs and incarcerationbased drug treatments in reducing crime rates among offenders [19-21].

1.2. Treatment Utilization and Criminal Recidivism among Offenders with Psychopathic Personality Traits

As mentioned above, research has highlighted the benefit of interventions targeting problematic substance use in order to reduce criminal behavior. However, interventions with the aim to reduce criminal behavior among offenders with psychopathic personality traits have yielded mixed results. Some studies have suggested that treatment fails to reduce criminal behavior in this population [22,23], whereas others have yielded more optimistic results. For example, Salekin proposed that particular treatment programs, including cognitive-behavioral and psychodynamic interventions were successful in reducing crime rates among offenders with psychopathic personality traits [24] and Skeem, Monahan, and Mulvey showed that mental health treatment reduced violent behavior among psychiatric patients regardless of psychopathic personality traits [25]. According to a recent review of the psychopathy research field, the pessimistic view on treatment effectiveness for this population has been the result of inappropriate research designs used to explore this topic [26].

Offenders with psychopathic personality traits commonly abuse substances [27]. Research has shown higher rates of attrition and relapse following substance abuse treatment participation among such individuals, relative to their non-psychopathic counterparts [28,29].

1.3. Psychopathic Personality Traits as Barriers to Treatment Utilization

Utilization of substance abuse treatment may be related to a variety of factors, both personal and contextual [30]. Facilitators and barriers to treatment (i.e. factors positively and negatively associated with treatment utilization) have been explored with the aim to predict who will and who will not utilize such treatment. The specific traits of psychopathy may hypothetically function as barriers to substance abuse treatment [31]. For example, individuals with traits such as impulsivity and proneness to boredom may not take treatment utilization seriously, which can result in an increased likelihood of withdrawing from treatment. In addition, individuals with features such as early behavior problems and criminal versatility commonly have difficulties in complying with treatment rules, which can result in treatment drop-out. Another personality trait included in psychopathy is grandiosity. People with this trait might fail to identify aspects of themselves that they need to change which in turn might inhibit treatment utilization. Finally, those with traits such as a lack of empathy and shallow effect may have difficulties in establishing a meaningful alliance with treatment providers, which in turn may lead to a failure to complete treatment. According to Douglas and Skeem, poor treatment utilization may predict future violence [5]. Thus, individuals with psychopathic personality traits may be regarded as having an elevated risk of re-offending based on their low likelihood of utilizing treatment and proneness to criminal behavior.

1.4. The Importance of Qualitative Studies in Treatment Research

In most substance abuse treatment research, the perspectives of the substance users remain ignored [30]. Qualitative studies are useful as they catch participants’ experiences in their own words, helping to yield a deep understanding of which factors that may facilitate and inhibit treatment utilization. Conducting qualitative studies may also be beneficial to improve retention rates and to add knowledge that may be used by clinicians and service providers in order to elaborate treatment strategies producing positive outcomes.

To conclude, offenders with mental health problems and problematic substance use have multiple treatment needs and may also have psychopathic personality traits. The presence of such traits might imply a proneness to criminal recidivism and/or a resistance to utilize treatment. As many of the psychopathic personality traits hypothetically may function as barriers to treatment utilization, the presence of such traits may be of relevance for treatment perceptions. According to our knowledge, there is a lack of qualitative studies exploring how offenders with mental health problems, problematic substance use and psychopathic personality traits perceive treatment.

1.5. Aims and Research Questions

The aim of this study was to explore perceptions of substance abuse treatment among Swedish offenders with mental health problems, problematic substance use and various degrees of psychopathic personality traits. The following research questions were addressed:

Which are the perceived facilitators and barriers to treatment utilization among the participants?

What are their perceptions of treatment utilization?

Which elements of treatment are perceived as having an impact on ongoing problems?

Are there any differences in the above treatment perceptions between those with a high degree of psychopathic personality traits and those with a low degree of such traits?

2. METHOD

2.1. Study Design and Sampling

A qualitative study design was chosen, which is considered appropriate when the aim is to capture participant perspectives in an under researched area or to evaluate and improve existing clinical practice [32]. For data collection, in-depth, semi-structured interviews were conducted.

The study was conducted within the larger ongoing prospective MSAC-study; a Swedish research program that explores the relevance of substance abuse treatment among offenders with mental health problems and problematic substance use [33]. The participants were recruited between 2006 and 2009, and inclusion criteria involved 1) having been referred to a forensic psychiatric assessment2, 2) having a record of hazardous use of alcohol and/or illicit drugs according to the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT [34]) and the Drug Use Disorders Identification Test (DUDIT [35]) and 3) being registered in the Stockholm County (population: 1.9 million). Hazardous use of alcohol was defined as an AUDIT score of 8 or more points for men and 6 or more points for women, whereas hazardous use of illicit drugs was defined as a DUDIT score of 1 point or more for both men and women [34,36].

Participants of the present study were sampled among MSAC-participants subjected to the Swedish translation of the Psychopathy Checklist Revised (PCL-R) (n = 158) for assessment of psychopathic personality traits [7]. The PCL-R is a semi-structured interview, which consists of 20 items, scored 0, 1 or 2, to indicate absence, partial presence or presence, respectively, of the trait referenced in the item. The scoring relies on the interview with the subject as well as on additional file information. Within the MSAC-study, the additional file information comprised the final report of the forensic psychiatric assessment (involving information on parameters such as current and previous social and mental health status), which was used in order to complement the interview data. In Scandinavian countries, a cut-off score of 26 PCL-R points has been suggested as valid in order to define psychopathy [37]. Also, 0 to 19 PCL-R points and 20 to 29 PCL-R points have been suggested as an indication of low and moderate psychopathy, respectively [38].

The PCL-R can be divided into two factors; Factor 1, which involves interpersonal and affective traits and Factor 2 that deals with features referring to an antisocial and impulsive lifestyle [7]. The total score of Factor 1 is 16 points whereas Factor 2 has a total score of 20 points. Two of the items (many short-term marital relationships and sexual promiscuity) do not load on any of the two factors. The PCL-R has established good psychometric properties in various offender populations including Swedish offenders with mental health problems [12,39].

Using the total score of all PCL-R items, we subdivided MSAC-participants into two groups with the latter serving as a reference group: 1) participants with a high degree of psychopathic personality traits, i.e. ≥26 points on the PCL-R, and 2) participants with a low degree of psychopathic personality traits, i.e. 0 - 5 points on the PCL-R. Among the 158 participants subjected to the PCL-R, 19 individuals displayed a high degree of psychopathic personality traits and 21 individuals displayed a low degree of such traits. Thus, 40 individuals were eligible for inclusion in the present study.

Among the individuals eligible for inclusion, females (n = 2) were not invited to participate, due to the fact that none displayed high PCL-R scores and our assumption that it would be somewhat complicated to analyze the results from a mixed gender study cohort. The remaining 38 individuals divided into the two above groups were ranked in ascending order according to their study ID numbers assigned at recruitment to the MSAC-study. Starting with those with the lowest study ID numbers in each group, the individuals were contacted individually by telephone by the first author of the study and were invited to participate and told that the interview would concern their perceptions of treatment. Hence, the individuals were consecutively recruited to the study. Among the 38 individuals, 17 were contacted of which twelve accepted study participation and five declined. Given that the data analysis chosen for the study (see below) advocates fairly small samples sizes, i.e. about ten participants [40], we decided not to recruit further individuals. Thus, the remaining 21 individuals were not contacted for study participation. Among the twelve individuals included in the study, six displayed a high degree of psychopathic personality traits and six displayed a low degree of such traits.

All MSAC-participants who had been subjected to the PCL-R had also been interviewed with the Swedish translation of the sixth version of the Addiction Severity Index (ASI-6 [41,42]); a semi-structured interview used by various professionals and researchers to assess current and prior problematic use, problems related to such use as well as the need for treatment. The interview covers items within the following nine domains: medical, employment, alcohol, drugs, legal, psychiatric, and family/social domains, with the latter subdivided into family/social problems, family/social support and child problems. According to recent studies the ASI-6 has adequate psychometric properties [41,43].

Research assistants with a BA degree or with extensive experience of forensic psychiatric care carried out PCL-R and ASI-6 interviews. The interviews were conducted in prison settings or at forensic psychiatric clinics shortly before the participants were to be released into the community. The interviewers had participated in three days of formal training in administering the instruments.

2.2. Interview Procedure

The semi-structured in-depth interviews were conducted by the first author of the study, and took place at cafés in the Stockholm city center as well as in prison and remand settings.

In order to ensure minimal distraction, the interviews were conducted at cafés with few customers and low levels of noise, and were performed in private areas of the cafés. Also, the interviews performed in the prison and remand settings took place in separate interview rooms where only the interviewer and the informant were present. An interview-guide was developed by the authors and used during all interview sessions (see Appendix). The guide was based on the study objectives as well as on literature reviews of the research field and was used in order to provide structure to the interviews and to ensure that similar topics were covered with all informants. However, during each interview, additional questions were also asked to elucidate the informants’ story. At the end of each interview, the interviewer gave a brief summary of what the informant had talked about. The informant was then given the opportunity to give feedback and to correct any misinterpretation that might have arisen. All interviews lasted 94 minutes on average (SD = 15.74 minutes, range = 69 - 118 minutes), were recorded using an mp3-player and were transcribed verbatim. Significant pauses and laughs during the interview were also noted in the transcripts whereas identifiable features were omitted. Each interview generated 18 to 34 pages of typewritten text.

2.3. Participants

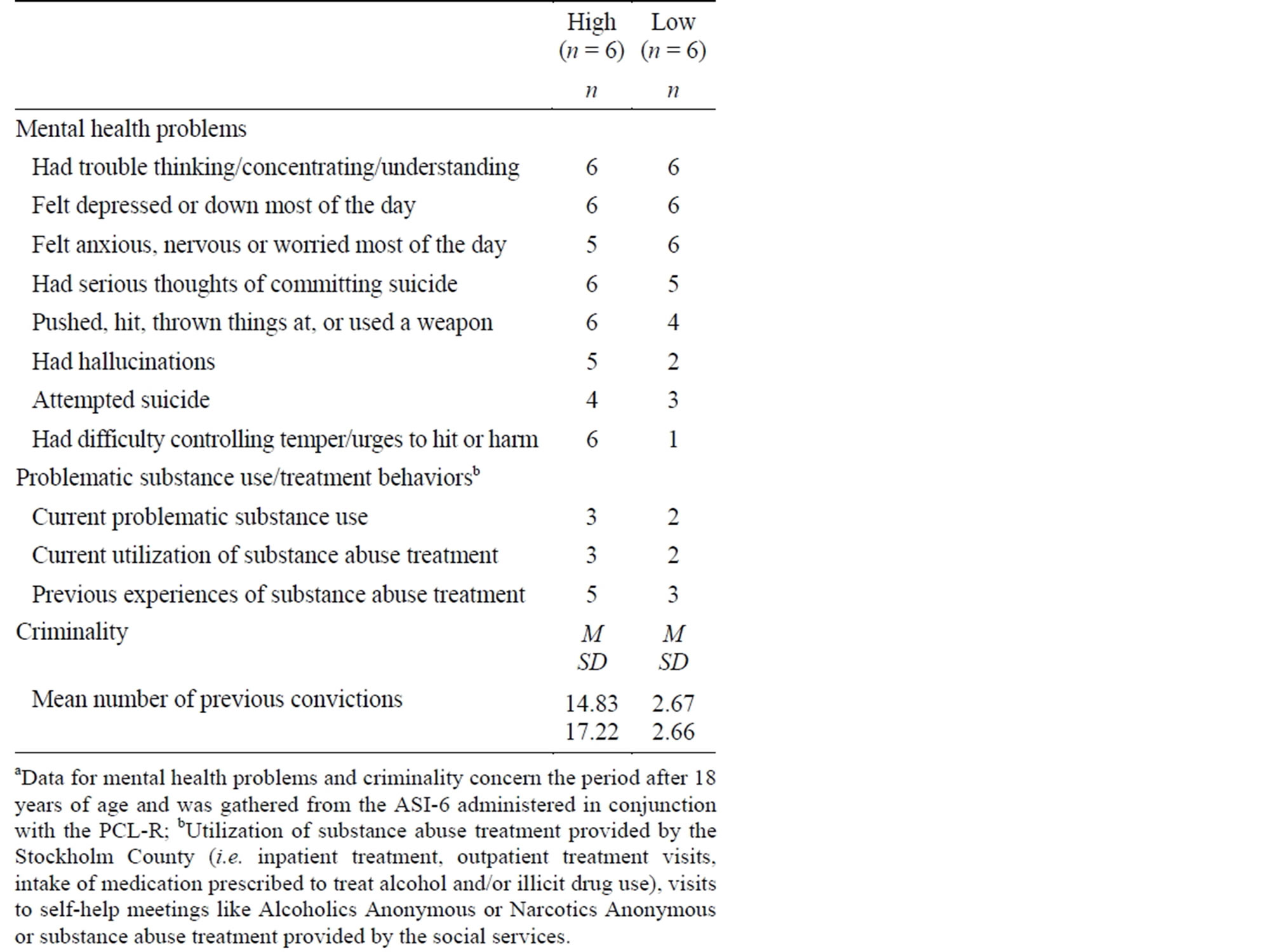

Twelve male individuals participated in study. The mean age of all participants was 38 years (SD = 15.60 years, range = 23 - 65 years). Four were born outside of Sweden. Two of the participants were in prison, one was on remand, and the remaining individuals resided in the community. Among the six individuals who displayed a high degree of psychopathic personality traits, the mean PCL-R score was 27.17 (SD = 1.83) and the mean Factor 1 and Factor 2 scores were 7.83 (SD = 0.98) and 15.67 (SD = 0.81), respectively. Table 1 presents self-reported mental health problems, problematic substance use, treatment behaviors and criminality among participants with a high and low degree of psychopathic personality traits, respectively.

As illustrated, all participants had experienced cognitive problems and had felt depressed after 18 years of age. At the time of the in depth-interview, five informants had a problematic substance use and five were utilizing substance abuse treatment. All participants had had a record of hazardous use of alcohol and/or illicit drugs at the time of inclusion to the MSAC-study. Eight participants had previous experiences of utilizing substance abuse treatment. The subgroup with a high degree of psychopathic personality traits had about 15 previous convictions on average, compared to those with a low

Table 1. Self-reported mental health problems, problematic substance use, treatment behaviors and criminality among participants with a high and low degree of psychopathic personality traits, respectivelya (n = 12).

degree of such traits who had about three.

2.4. Data Analysis

The data analysis was conducted using Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA [44]). IPA is designed to explore participants’ views and experiences of a certain topic. As such, it is concerned with illustrating personal perceptions, rather than producing an objective statement of the topic. Access to such perceptions is dependent on the researcher’s own preconceptions through a process of interpretative activity.

IPA is not a prescriptive approach but provides a set of flexible guidelines than can be adapted in light of the study aim [44]. With reference to these guidelines, the analysis was performed in four stages. In the first stage, a template was defined which would direct the analysis in the subsequent stages [45]. For defining the template, the authors, independently of one another, read four transcripts several times and marked content in the transcripts that was related to the research questions. The authors then met to assess the agreement in their markings. The agreement varied between 77% and 91%. The authors further discussed which content that was to be included in the template. It was decided that content involving perceptions of substance abuse treatment provided by institutions (e.g. the county council or the social services) or voluntary organizations (e.g. Alcoholics Anonymous or Narcotics Anonymous) should be included. The final template was then used for further identifying segments of text to be subject to analysis.

During the second stage, all transcripts were read until a sense of whole was gained. During reading, keywords were noted in the margins. The keywords were then transformed into preliminary sub-themes which were based on what the informant talked about without interpretation of the narratives. The preliminary sub-themes emerged both from raw data and from the concepts a priori defined in the template.

In the next stage, an interpretative approach was applied. Thus, the names previously given to the subthemes were changed to reflect a more latent content of the narratives. Constantly, all interviews were re-read and the content of the narratives was categorized as either belonging or not belonging to the sub-themes already emerged. Content that did not fit into the already existing sub-themes was categorized into new subthemes.

During the fourth stage, all sub-themes were clustered together into themes of a more general content. Those sub-themes that did not fit any of the themes were removed. Differences in perceptions of treatment between participants with a high and low degree of psychopathic personality traits were specially noted upon. All participants were given a pseudonym so that their quotes could be traced throughout the transcriptions without identifying the individuals. Participants categorized as having a high degree of psychopathic personality traits, were given a pseudonym with the initial letter “H” (in the text referred to as the H-group) whereas participants classified as having a low degree of psychopathic personality traits were given a pseudonym with the initial letter “L” (in the text referred to as the L-group). Clustering of sub-themes resulted in seven final themes. During stages two, three and four, the first author of the study performed the analysis, but regularly met with the others in order to discuss interpretations of segments of text and to further refine sub-themes, themes and clustering of themes. The final themes and their sub-themes are described in more detail in the result section below.

2.5. Ethical Considerations

All participants of the present study had signed a written consent form at recruitment to the MSAC-study. Ethical permission for the study was granted by the Regional Ethical Review Board in Stockholm (permit no. 2005/ 1265-31).

3. RESULTS

3.1. Feeling like an Outsider

Informants from both the Hand the L-group identified that the long wait for treatment had contributed to feeling like an outsider in relation to the treatment system. Some stated that lengthy phone queues when calling treatment providers, as well as having to spend several hours in waiting rooms before treatment appointments created a feeling of limited treatment access. Both groups also described that an ongoing problematic substance use contributed to the outsider feeling. The informants stated that they wanted to get access to the treatment system, but that a hectic life-style associated with ongoing substance use made it hard for them to manage to seek treatment.

To some H-participants, the concept of treatment had no significance. It was mainly perceived as a word used by authorities and caregivers and sometimes perceived as a term referring to a meaningless “cosmetic” activity, in the sense that treatment programs only existed for the sake of providing society with a positive image of treatment allocation. Several H-participants had also experienced a struggle with caregivers and social services when seeking treatment, describing that efforts were needed to make caregivers and social services listen to their problems, and to give them treatment access. Howard stated the following:

I had to struggle with them [the social services] for an entire year. I even had to smoke a joint in front of them so they would get it; that I needed treatment. (Howard)

Finally, the H-informants described that treatment providers seemed to want to hand over the patient’s problems to other treatment providers, which resulted in them being excluded from many treatment services and created a situation where one could risk falling through the cracks in the treatment system.

3.2. Psychological Barriers to Treatment Utilization

Among informants from both groups, keeping up appearances was viewed as one barrier to treatment utilization. The informants stated that they had kept a straight face rather than showing how they actually felt and seeking help. One could be reluctant to ask for help due to too much self-pride and try to handle a problem on one’s own, as exemplified by the following statements:

Yes, it’s humiliating, that has been my opinion my whole life. I’m a man, I cannot ask for help. Unfortunately, that’s the way it is. And being proud, that fake self-pride; “I don’t need any help, I can make it on my own”. (Harold)

No, I’ve been at home, thinking, and spending time with my family… Just trying to forget and make it on my own without seeking any help. (Louis)

Lack of confidence in treatment was perceived as a barrier to treatment utilization among the H-participants, who viewed treatment to be non-responsive to treatment needs or ineffective in reducing or eliminating problems. As an example, Hank said:

I don’t have enough confidence in treatment providers. In treatment you should be able to open up and talk about your problems, but then they say that they’re not bound by professional secrecy. No, I don’t want that kind of treatment. (Hank)

Members of the H-group also pointed out the perceived stigma of treatment utilization as a barrier. For example, one participant described that he was unwilling to utilize treatment at an outpatient facility for problematic substance use and psychiatric problems, because he was afraid of being labeled as a “mental case” and concerned about what other people would think of him. In addition, lack of willingness to change served as a treatment barrier among the H-participants who told that their reluctance to give up their criminal life-style prevented them from seeking treatment. Finally, according to some L-participants, lack of perceived treatment need served as a factor that contributed to not seeking treatment, as suggested by the following quotations:

No, that [utilizing substance abuse treatment] wouldn’t be relevant. I have no such problems. (Leonard)

No, my alcohol consumption is under control. I don’t need any treatment. (Lance)

3.3. Turning Points

Informants from both groups described that having hit the rock bottom had acted as a turning point for a change of attitudes towards treatment. Realizing that one had an ongoing problematic substance use, or having gone through a crisis such as having an overdose, or losing custody of a child, had facilitated a more positive attitude towards treatment utilization. Informants of both groups also described turning points for a change of treatment behavior which included being subjected to formal and informal pressures. The participants stated that they had been subjected to legal pressures, as they had been sentenced to treatment by court, and described that they had experienced pressures from other authorities such as the social services. For instance, Harry acknowledged that he had entered treatment in order to avoid being committed to compulsory treatment3:

The social services forced me more or less. They told me that if I didn’t go there voluntarily they would commit me to compulsory treatment. Therefore, there wasn’t much to consider. It’s never fun being treated under such circumstances. (Harry)

In addition, both groups mentioned that they had experienced pressures to participate in treatment from informal actors such as family or friends. Liam said the following:

I only did it [initiated treatment] for the sake of my friends. Because they wanted me to go there, and in some way I wanted to relieve them from their responsibility. (Liam)

Finally, among informants from both groups, identifying a treatment goal was perceived as an incentive for a change of treatment behavior. Goals that were mentioned included wanting to stop using illicit drugs altogether or wanting to achieve a better social situation (housing or employment); circumstances that all had initiated treatment utilization.

3.4. Treatment Context Matters

Informants from the Has well as the L-group complained about the lack of activities in treatment facilities. Due to lack of activities, treatment utilization was perceived as an experience with little significance, as described by Henry and Lawrence:

When I was at the detoxification unit, all I did was walking down the hall, back and forth. I don’t know if that is what you call treatment... (Henry)

I mean, going to the substance abuse clinic, all you do is complain. Why can’t we all [in treatment] get together and do something? Like an activity. They [treatment providers] could try out other methods. Some of us would appreciate that. (Lawrence)

One view expressed by both groups was that there was too much focus on medication; i.e. that medication was commonly delivered in favor of providing other elements of treatment such as psychotherapy. L-group informants stated that there was usually a poor physical treatment environment within treatment settings. Worn-out treatment facilities with unpainted walls as well as old furniture gave a negative impression. Some even claimed that their health had worsened when they had spent time in such an environment.

3.5. The Perceived Imbalance between Caregivers and Caretakers

Informants from both groups described occasions when they had been subjected to control by treatment providers and social services. Being subjected to control could be perceived as inconvenient, for instance when one had to provide urine specimens or blood samples to prove being abstinent. Some participants also stated that they had been subjected to control in order to receive various interventions from the social services, sometimes perceived as rather irrelevant. Members of the two groups had somewhat different perceptions of the control requirements imposed on them. The L-informants described that such requirements were manageable, although sometimes inconvenient, whereas the H-participants said that they were often difficult to fulfill. Lloyd and Harold stated the following:

In general, it doesn’t bother me. It’s done quite easily, and there’s nothing to worry about. I just go there and leave my samples, and I keep my appointments. That has worked well. (Lloyd)

Although I was homeless and a substance abuser, they [the social services] claimed that I did not fit in to the category they gave rental apartments to […] It’s like this; you have to be clean for one year before you can get an apartment. And that’s not very easy when you’re homeless; that is, to stay clean when you have to sleep at toilets and in basements… (Harold)

Participants from both groups also described they had been subject to prejudice from caregivers. The H-informants had felt that the prejudice involved being viewed as a criminal whereas the L-informants identified other types of prejudice, such as caregivers’ views that a having a problematic substance use was ones’ own fault. The H-group informants also described a sense of inferiority towards caregivers. Caregivers could be viewed as superior, deciding how the treatment should be assigned. Harry stated:

In treatment, I’m automatically placed in an inferior position. I have to prove this and that. It’s me against them [the treatment providers], somehow. They can decide whatever they want. (Harry)

3.6. A Variety of Positive Outcomes of Treatment Utilization

Informants from both groups identified mental/emotional outcomes of treatment utilization such as increased confidence and self-esteem.

Among the H-informants, the mental/emotional outcomes that were mentioned also involved an increased understanding of one’s behavior:

I got a deeper insight, and I got to know why I behaved like I did and not only what my behavior was like. (Hugo)

Among both groups, the social outcomes involved descriptions of how caregivers had supported them to re-integrate into society and to remain drug-free. Finally, both groups of informants had experienced instrumental outcomes, referring to various privileges in prison, such as change of environment, or faster release from prison.

3.7. Perceptions of the Ideal Treatment

The informants also discussed which components that should be part of the ideal treatment, which in turn would have an impact on ongoing problems. Both groups stressed the importance of an individualized and allencompassing treatment, i.e. one that should be able to target the individuals’ specific treatment needs, and deal with housing, economy, complete abstinence from alcohol or illicit drugs, and target primary needs such as food and clothing. Moreover, psychotherapy, i.e. the opportunity to engage in a structured dialogue with a caregiver over a longer time period, was identified by both groups as another prerequisite for a successful treatment outcome. According to the informants, psychotherapy would not only be beneficial for the patient but also for caregivers as it might increase caregivers’ understanding of the patient perspective. Also, a therapeutic alliance4 built on empathy and trust, was considered to be an essential factor. Unique to the H-informants was the opinion that they wanted caregivers to help increase their motivation and to treat them with respect:

[I want to be treated] like a normal citizen, with respect and not like I am an animal. Because I am no worse than others just because I have been a junkie, a drug addict, for ten years. (Harry)

Finally, both groups stressed the importance of structure in the treatment system, involving rules and checkups of patients. Such structure was perceived to prevent relapse into alcohol and/or illicit drugs.

4. DISCUSSION

The present study explored treatment perceptions among offenders with mental health problems, problematic substance use and various degrees of psychopathic personality traits. The findings suggest that some treatment perceptions may vary with degree of psychopathic personality traits. For instance, the two groups had different perceptions of the control requirements imposed upon them; the L-informants stated that the requirements were rather manageable whereas the H-participants said that they were often difficult to fulfill. In addition, the H-informants stated that they felt inferior towards treatment providers and that they wanted caregivers to treat them with respect.

In treatment research, it has been suggested that the patient-caregiver relationship is characterized by asymmetry of power, meaning that the caregiver knows better than the patient what he or she needs and decides how the treatment should be assigned [47]. In addition, a central and unique feature of treatment that focus problematic substance use is the control of patients (i.e. control of abstinence) which relies heavily on regulations and instructing activities in order to produce positive outcomes [48]. In the present study, conforming to asymmetry of power and control may have been perceived as difficult by the H-participants [31]. Antisocial features, e.g. early behavior problems and criminal versatility may have interfered with the capacity or willingness to comply with treatment rules, and traits such as proneness to boredom or impulsivity may have contributed to a failure to fully engage in treatment.

According to Skeem and colleagues, treatment programs should be modified in order to suit offenders with psychopathic personality traits [25]. Among individuals with mental health problems and co-occurring substance abuse, low-demand treatment programs with high flexibility and little or no control of patients have produced better treatment retention, better substance use outcomes and less criminal activity, relative to high-demand treatment programs [49]. The results of the present study, which indicated that the H-group may have had difficulties in conforming to control, may be interpreted as if low-demand treatment programs could be suitable also for them. Moreover, the H-participants stated that they wanted caregivers to help increase their motivation. It has been suggested that treatment programs for individuals with psychopathic personality traits should focus on motivation to change as these individuals generally lack motivation [13]. Rather than viewing them as incurable cases, clinicians should acknowledge that they require time and effort in treatment. These suggestions are also in line with the findings of the present study.

There were many similarities in treatment perceptions between the two groups of participants. As an example, informants from both groups shared the view on what factors that should be part of the “ideal treatment”. The results indicate that degree of psychopathic personality traits may not be the only dimension that influences treatment perceptions. However, the presence of some particular traits included in the psychopathy concept, also present among non-psychopaths (e.g. impulsivity, proneness to boredom) may be relevant in explaining certain treatment perceptions.

Many of the findings of the present study also support previous research. Among individuals with problematic substance use, stigma [50], and lack of willingness to change [51] have been suggested as barriers to substance abuse treatment whereas having hit the rock bottom [52] and formal and informal pressures [53] have been recognized as turning points to treatment, or treatment facilitators. Thus, both Hand L-participants of this study appear to be similar to other individuals with problematic substance use with regard to certain treatment perceptions. However, the sample size was limited and more research is needed in order to generalize this finding.

Offenders with mental health problems, problematic substance use and various degrees of psychopathic personality traits are of great concern to society. They have multiple treatment needs, and the sometimes rather poor outcomes of rehabilitation are costly, including expenditures for legal processes, prison care, social services, psychiatric care and substance abuse treatment. Of importance are the contribution of the clients’ own views on treatment and what could be done to improve outcomes. The results of the study can provide knowledge for clinicians and administrators working with treatment planning and allocation of treatment. Such knowledge may be used to elaborate treatment strategies, and to improve treatment participation and retention, which in turn could lead to reduced crime rates and other positive outcomes in this population.

Methodological Considerations

The study was conducted using established validation standards commonly applied in IPA [44]. Regular meetings between the authors were held to ensure ongoing critique of the work and credibility of emergent themes. Only the first author had information on which participants were categorized as having a high or low degree of psychopathic personality traits, which also served as a means to achieve credibility. To ensure the coherence of the results, contradictions in the data were noticed and included in the analysis, and the interpretations were constantly checked back to ensure that they were warranted by the data.

All interviews were conducted in settings with minimal distraction. Some participants were familiar with the interviewer as she had previously encountered them in association with recruitment to the MSAC-study. These circumstances may have contributed to a relaxing atmosphere in which the participants could speak freely about their treatment perceptions. As each participant was given the opportunity to give feedback on the interviewer’s summary at the end of each interview, the risk of misinterpretation may be considered as low, assuring respondent validation. However, the results may have been affected by recall bias, as psychopathy is associated with manipulative behavior and lying [7]. Data collection through another source such as ward observations, could have contributed to further support of the findings. Moreover, an additional interview of each participant, conducted by a second interviewer, may have counter-acted subjectivity and provided means for follow-up questions in other unprobed areas.

The study aim was to explore perceptions of substance abuse treatment. Four participants had no experience of such treatment, but were represented in the first two themes of the results. As IPA aims to explore individual experiences and views on a specific topic of interest, the inclusion of these participants was considered as justified [44].

Moreover, IPA is often used in studies with fairly homogeneous samples, but may also be used when the aim is to compare two groups regarding their experiences or views on a certain topic, obviously requiring heterogeneity among the participants [44]. In such cases, Smith and colleagues emphasize the importance of assuring that the two groups are homogenous in other aspects than the variable that separates them. The sample of the present study was homogenous in that all participants were offenders with (current and/or prior) mental health problems and problematic substance use, and heterogeneous in that they had various degrees of psychopathic personality traits. In line with the above recommendations, we believed that the use of IPA would be appropriate for our study. Moreover, we observed many similarities in treatment perceptions among Hand L-participants. As stated, the sample was homogeneous in several aspects, which may have contributed to these findings. In addition to high and low PCL-R scores, other factors such as mental health status and the presence of a problematic substance use may need to be considered in order to explain certain treatment perceptions.

The H-participants displayed more features of antisocial and impulsive behavior than affective and interpersonal traits of psychopathy. According to Skeem and Cooke, the psychopathy construct merely includes interpersonal and affective traits [8]. In line with this view, the H-participants may be regarded as more antisocial/impulsive than truly psychopathic. However, according to Hare’s definition of psychopathy, considering impulsive and antisocial behavior to be a part of the construct [9], they may be regarded as psychopathic. In the study, however, we referred to the two participant groups as having high and low degrees of psychopathic personality traits, rather than being psychopathic and nonpsychopathic. Future studies should include offenders with more affective and interpersonal PCL-R traits in order to explore whether psychopathic personality traits influence treatment perceptions.

Furthermore, our study was conducted with a purposive sample of offenders with various degrees of psychopathic personality traits. Due to the nonrandomized sample used, the results are not representative for a wider population. However, achieving a representative result is not the aim of most approaches to qualitative research [32]. Instead, the aim is to produce an in-depth analysis of the accounts of a small number of participants. Although the findings may not be generalized to a larger population, the findings can be generalized to other similar contexts, as suggested by the transferability principle, commonly applied in qualitative research [54]. Thus, the treatment perceptions suggested may not be present among all offenders with mental health problems, problematic substance use and various degrees of psychopathic personality traits but occur among individuals utilizing treatment in other clinical settings. Also, the treatment perceptions suggested do not reflect actual treatment behavior. In order to draw any conclusions about the relationship between psychopathic personality traits and treatment behavior, quantitative studies that include control groups and randomization of participants to treatment settings should be conducted.

5. CONCLUSION

Among offenders with mental health problems and problematic substance use, some psychopathic personality traits may be relevant in explaining certain treatment perceptions. The degree of psychopathic personality traits may, however, not be the only dimension that influences treatment perceptions. The results highlight the complexity of the relationship between the individual and the treatment system and may serve as a starting point for further studies on this topic.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Preparation of this article was supported by the Swedish Council for Working Life and Social Research (Grant 2005/5:11). The authors thank John Monahan, PhD, University of Virginia for support and advice.

REFERENCES

- Elbogen, E.B. and Johnson, S.C. (2009) The intricate link between violence and mental disorder: Results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. Archives of General Psychiatry, 66, 152-161. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2008.537

- Chiles, J.A., Von Cleve, E., Jemelka, R.P. and Trupin, E.W. (1990) Substance abuse and psychiatric disorders in prison inmates. Hospital and Community Psychiatry, 41, 1132-1134.

- Putkonen, A., Kotilainen, I., Joyal, C.C. and Tiihonen, J. (2004) Co morbid personality disorder and substance use disorders of mentally ill homicide offenders: A structured clinical study on dual and triple diagnoses. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 30, 59-72. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a007068

- Douglas, K.S., Guy, L.S. and Hart, S.D. (2009) Psychosis as a risk factor for violence to others: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 135, 679-706. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0016311

- Douglas, K.S. and Skeem, J.L. (2005) Violence risk assessment. Getting specific about being dynamic. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 11, 347-383. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/1076-8971.11.3.347

- Porter, S. and Porter, S. (2007) Psychopathy and violent crime. In: Hervé, H. and Yuille, J.C., Eds., The Psychopath: Theory, Research and Practice, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers, Mahwah, 287-300.

- Hare, R.D. (2003) Manual for the revised psychopathy checklist. 2nd Edition, Multi-Health Systems, Toronto.

- Skeem, J.L. and Cooke, D. (2010) Is criminal behavior a central component of psychopathy? Conceptual directions for resolving the debate. Psychological Assessment, 22, 433-445. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0008512

- Hare, R.D. and Neumann, C.S. (2010) The role of antisociality in the psychopathy construct: Comment on Skeem and Cooke. Psychological Assessment, 22, 446-454. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0013635

- Blackburn, R., Logan, C., Donnelly, J. and Renwick, S. (2003) Personality disorders, psychopathy and other mental disorders: Co-morbidity among patients at English and Scottish high-security hospitals. The Journal of Forensic Psychiatry and Psychology, 14, 111-137. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/1478994031000077925

- Hemphill, J.F., Hare, R.D. and Wong, S. (1998) Psychopathy and recidivism: A review. Legal and Criminological Psychology, 3, 139-170. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8333.1998.tb00355.x

- Tengström, A., Grann, M., Långström, N. and Kullgren, G. (2000) Psychopathy (PCL-R) as a predictor of violent recidivism among criminal offenders with schizophrenia. Law and Human Behavior, 24, 45-58. http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/A:1005474719516

- Salekin, R.T., Worley, C. and Grimes, R.D. (2010) Treatment of psychopathy: A review and brief introduction to the mental model approach for psychopathy. Behavioral Sciences and the Law, 28, 235-266. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/bsl.928

- Hartwell, S.W. (2004) Triple stigma: Persons with mental illness and substance abuse problems in the criminal justice system. Criminal Justice Policy Review, 15, 84-99. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0887403403255064

- Lindqvist, P. (2007) Mental disorder, substance misuse and violent behavior: The Swedish experience of caring for the triply troubled. Criminal Behavior and Mental Health, 17, 242-249. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/cbm.658

- Ruiz, M.A., Douglas, K.S., Edens, J.F., Nikolova, N.L. and Lilienfeld, S.O. (2012) Co occurring mental health and substance use problems in offenders: Implications for risk assessment. Psychological Assessment, 24, 77-87. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0024623

- Alm, C., Eriksson, Å., Palmstierna, T., Kristiansson, M., Berman, A.H. and Gumpert, C.H. (2011) Treatment patterns among offenders with mental health problems and substance use problems. Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research, 38, 497-509. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11414-011-9237-z

- Gumpert, C.H., Winerdal, U., Grundtman, M., Berman, A.H., Kristiansson, M. and Palmstierna, T. (2010) The relationship between substance abuse treatment and crime relapse among individuals with suspected mental disorder, substance abuse, and antisocial behavior. Findings from the MSAC Study. International Journal of Forensic Mental Health, 9, 82-92. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14999013.2010.499557

- Holloway, K.R., Bennet, T.H. and Farrington, D.P. (2006) The effectiveness of drug treatment programs in reducing criminal behavior: A meta-analysis. Psicothema, 18, 620- 629.

- Mitchell, O., Wilson, D.B. and Mackenzie, D.L. (2007) Does incarceration-based drug treatment reduce recidivism? A meta-analytic synthesis of the research. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 3, 353-375. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11292-007-9040-2

- Prendergast, M.L., Podus, D., Chang, E. and Urada, D. (2002) The effectiveness of drug abuse treatment: A meta-analysis of comparison group studies. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 67, 53-72. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0376-8716(02)00014-5

- Rice, M., Harris, G. and Cormier, C. (1992) An evaluation of a maximum security therapeutic community for psychopaths and other mentally disordered offenders. Law and Human Behavior, 16, 399-412. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF02352266

- Young, M., Justice, J., Erdberg, P. and Gacono, C. (2000) The incarcerated psychopath in psychiatric treatment: management or treatment? In: Gacono, C., Ed., The Clinical and Forensic Assessment of Psychopathy: A Practitioner’s Guide, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers, Hillsdale, 313-331.

- Salekin, R.T. (2002) Psychopathy and therapeutic pessimism: Clinical lore or clinical reality? Clinical Psychology Review, 22, 79-112. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0272-7358(01)00083-6

- Skeem, J.L., Monahan, J. and Mulvey, E.P. (2002) Psychopathy, treatment involvement, and subsequent violence among civil psychiatric patients. Law and Human Behavior, 26, 577-603. http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/A:1020993916404

- Skeem, J.L, Polaschek, D., Patrick, C.J. and Lilienfeld, S.O. (2011) Psychopathic personality: Bridging the gap between scientific evidence and public policy. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 12, 95-162. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1529100611426706

- Taylor, J. and Lang, A.R. (2006) Psychopathy and substance use disorders. In: Patrick, C.J., Ed., Handbook of Psychopathy, Guilford Press, New York, 495-511.

- Alterman, A.I., Rutherford, M., Cacciola, J.S., McKay, J. and Boardman, C. (1998) Prediction of 7 months methadone maintenance treatment response by four measures of antisociality. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 49, 217-223. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0376-8716(98)00015-5

- Richards, H.J., Casey, J.O. and Lucente, S.W. (2003) Psychopathy and treatment response in incarcerated female substance abusers. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 30, 251-276. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0093854802251010

- Tsogia, D., Copello, A. and Orford, J. (2001) Entering treatment for substance misuse: A review of the literature. Journal of Mental Health, 10, 481-499. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09638230120041254

- Thornton, D. and Blud, L. (2007) The influence of psychopathic traits on response to treatment. In: Hervé, H. and Yuille, J.C., Eds., The Psychopath: Theory, Research and Practice, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers, Mahwah, 411-428.

- Maxwell, J.A. (2005) Qualitative research design. An interactive approach. 2nd Edition, Sage, Thousand Oakes.

- Durbeej, N., Berman, A.H., Gumpert, C.H., Palmstierna, T., Kristiansson, M. and Alm, C. (2010) Validation of the alcohol use disorders identification test and the drug use disorders identification test in a Swedish sample of suspected offenders with signs of mental health problems: Results from the mental disorder, substance abuse and crime study. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 39, 364-377. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2010.07.007

- Saunders, J.B., Aasland, O.G., Babor, T.F., de la Fuente, J.R. and Grant, B.F. (1993) Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): WHO collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption. Addiction, 88, 791-804. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02093.x

- Berman, A.H., Bergman, H., Palmstierna, T. and Schlyter, F. (2005) Evaluation of the Drug Use Disorders Identification Test (DUDIT) in criminal justice and detoxifications settings and in Swedish population sample. European Addiction Research, 11, 22-31. http://dx.doi.org/10.1159/000081413

- The National Board of Health and Welfare (2007) Nationella riktlinjer för missbruksoch beroendevård: Vägledning för socialtjänstens och hälsooch sjukvårdens verksamhet för personer med missbruksoch beroendeproblem [Swedish national guidelines for treatment of substance abuse and dependence]. The National Board of Health and Welfare, Stockholm.

- Grann, M., Långström, N., Tengström, A. and Stålenheim, E.G. (1998) Reliability of file based retrospective ratings of psychopathy with the PCL-R. Journal of Personality Assessment, 70, 416-426. http://dx.doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa7003_2

- Hare, R.D. (1991) The Hare PCL-R: Rating booklet. MultiHealth Systems, Toronto.

- Fulero, S. (1995) Review of the hare psychopathy checklist-revised. In: Conoley, J.C. and Impara, J.C., Eds., Twelfth Mental Measurements Yearbook, Buros Institute, Lincoln, 453-454.

- Smith, J.A., Jarman, M. and Osborn, M. (1999) Doing interpretative phenomenological analysis. In: Murray, M. and Chamberlain, K., Eds., Qualitative Health Psychology: Theories and Methods, Sage, London, 218-241. http://dx.doi.org/10.4135/9781446217870.n14

- Cacciola, J.S., Alterman, A.I., Habing, B. and McLellan, A.T. (2011) Recent status score for version 6 of the Addiction Severity Index (ASI-6). Addiction, 106, 1588-1602. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03482.x

- Öberg, D., Sallmén, B., Berman, A.H. and Horner, C. (2006) Swedish version of the ASI-6. Adapted version, MSAC-project. Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm.

- Kessler, F., Cacciola, J.S., Alterman, A.I., Faller, S., SouzaFormigioni, M.L., Santos Cruz, M., et al. (2012) Psychometric properties of the sixth version of the Addiction Severity Index (ASI-6) in Brazil. Revsita Brasiliera de Psiquiatria, 34, 24-33.

- Smith, J.A., Flowers, P. and Larkin, M. (2009) Interpretative phenomenological analysis: Theory, method and research. Sage, London.

- Crabtree, B.F. and Miller, W.L. (1999) Doing qualitative research. Sage, Thousand Oakes.

- Martin, D.J., Garske, J.P. and Davis, M.K. (2000) Relation of the therapeutic alliance with outcome and other variables: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68, 438-450. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.68.3.438

- Kettunen, T., Poskiparta, M. and Gerlander, M. (2002) Nurse-patient power relationship: Preliminary evidence of patients’ power messages. Patient Education and Counseling, 47, 101-113. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0738-3991(01)00179-3

- Blomqvist, J., Palm, J. and Storbjörk, J. (2009) “More cure and less control” or “more care and lower costs”? Recent changes in services for problem drug users in Stockholm and Sweden. Drugs: Education, Prevention and Policy, 16, 479-496. http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/09687630802640305

- Brunette, M., Mueser, K.T. and Drake, R.E. (2004) A review of research on residential programs for people with severe mental illness and co-occurring substance use disorders. Drug and Alcohol Review, 23, 471-481. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09595230412331324590

- Bobrova, N., Rhodes, T., Power, R., Alcorn, R., Neifeld, E., Krasiukov, N., et al. (2006) Barriers to accessing drug treatment in Russia: A qualitative study among injecting drug users in two cities. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 82, 57-63. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0376-8716(06)80010-4

- Mowbray, O., Perron, B.E., Bohnert, A.S., Krentzman, A.R. and Vaughn, M.G. (2010) Service use and barriers to care among heroin users: Results from a national survey. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 36, 305-310. http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/00952990.2010.503824

- Cunningham, J.A., Sobell, L.C., Sobell, M.B. and Gaskinn, J. (1994) Alcohol and drug abusers’ reasons for seeking treatment. Addictive Behaviors, 19, 691-698. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0306-4603(94)90023-X

- Orford, J., Kerr, C., Copello, A., Hodgson, R., Alwyn, T., Black, R., Smith, M., Thistlethwaite, G., Westwood, A. and Slegg, G. (2006) Why people enter treatment for alcohol problems: Findings from UK alcohol treatment trial pre-treatment interviews. Journal of Substance Use, 11, 161-176.

- Morse, J.M. (1999) Qualitative generalizability. Qualitative Health Research, 9, 5-6. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/104973299129121622

APPENDIX

Please tell me about your current life situation (e.g. living conditions, employment, interests, and social networks).

What do you think is positive and less positive concerning your current life situation?

Are you currently experiencing any problems? If yes, what problems do you experience? How do you handle these problems?

Do you need support or help for anything? If yes, what for? What kind of support or help do you need?

What do you associate the word “treatment” with?

Is there anything that you need treatment for? If yes, what for? What kind of treatment do you need?

What role do alcohol and illicit drugs play in your life?

What do you associate the word “substance abuse treatment” with?

Are you currently utilizing any treatment for problematic substance use? If yes, please describe the treatment you receive?

What are your main reasons for utilizing substance abuse treatment/not utilizing such treatment?

How do you perceive utilizing substance abuse treatment/not utilizing such treatment?

How are you being approached by caregivers in your treatment program?

What are your treatment expectations?

What are your positive and negative experiences of substance abuse treatment?

What are the key characteristics of successful substance abuse treatment according to your opinion?

How do you perceive the health care provided in the Stockholm County and in Sweden?

What are your suggestions for improving the treatment system that focus on problematic substance use?

Is there anything that you would like to add/clarify/ emphasize based on what we have talked about?

Thank you for your participation!

NOTES

*Corresponding author.

1In this paper, the term problematic substance use is used to subsume various types of alcoholor drug-related problems, such as hazardous use, harmful use, substance abuse, and substance dependence.

2The Swedish Penal Code states that a person convicted of a crime committed under the influence of a severe mental disorder may not be sentenced to prison. Instead he or she should be referred to compulsory inpatient psychiatric care. The concept of severe mental disorder includes psychosis, severe depression with suicidal ideation and other types of disorders such as personality disorders with compulsive behavior or uncontrollable impulsivity. The court refers all suspects with a previous history or current indication of mental health problems for a forensic psychiatric assessment. The aim of this assessment is to evaluate whether a crime was committed under the influence of a severe mental disorder.

3In Sweden, the social services may report clients with problematic substance use to a special court that might sentence them to compulsory treatment. Compulsory treatment should be considered if there is an obvious risk that the client, due to ongoing use of alcohol or illicit drugs, might harm himor herself or others, and does not consent to voluntary treatment.

4A therapeutic alliance has been defined as the affective bond between patient and treatment provider and the patient’s and treatment providers’ ability to agree on treatment tasks and goals [46].