J. Biomedical Science and Engineering, 2010, 3, 20-26 doi:10.4236/jbise.2010.31003 Published Online January 2010 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/jbise/ JBiSE ). Published Online January 2010 in SciRes. http://www.scirp.org/journal/jbise Applications of a new In vivo tumor spheroid based shell-less chorioallantoic membrane 3-D model in bioengineering research Nzola De Magalhães1, Lih-Huei L. Liaw2, Michael Berns2, Vittorio Cristini3, Zhongping Chen2, Dwayne Stupack4, John Lowengrub5 1Department of Biomedical Engineering, University of California, Irvine, USA; 2Beckman Laser Institute and Medical Clinic, University of California, Irvine, USA; 3Health Sciences Center, University of Texas, Houston, Houston, USA; 4Moores Cancer Center, University of California, San Diego, USA; 5Department of Mathematics, University of California, Irvine, USA. Email: nmmagalh@uci.edu Received 20 September 2009; revised 11 November 2009; accepted 3 December 2009. ABSTRACT The chicken chorioallantoic membrane (CAM) is a classical in vivo biological model in studies of angio- genesis. Combined with the right tumor system and experimental configuration this classical model can offer new approaches to investigating tumor proc- esses. The increase in development of biotechnolo- gical devices for cancer diagnosis and treatment, calls for more sophisticated tumor models that can easily adapt to the technology, and provide a more accurate, stable and consistent platform for rapid quantitative and qualitative analysis. As we discuss a variety of applications of this novel in vivo tumor spheroid based shell-less CAM model in biomedical engineer- ing research, we will show that it is extremely versa- tile and easily adaptable to an array of biomedical applications. The model is particularly useful in quantitative studies of the progression of avascular tumors into vascularized tumors in the CAM. Its en- vironment is more stable, flat and has a large work- ing area and wider field of view excellent for imaging and longitudinal studies. Finally, rapid data acquisi- tion, screening and validation of biomedical devices and therapeutics are possible with the short experi- mental window. Keywords: CAM; Cancer; Spheroid; Optical Coherence Tomography; Photodynamic Therapy; Computational Modeling; Angiogenesis 1. INTRODUCTION Effective investigations in cancer research, whether in cancer dynamics, drug delivery, drug and diagnostic tool development, involves the use biological models that closely reflect realistic solid tumors. While in vitro models may not provide a complete as- sessment of the processes that occur only in the envi- ronment of solid tumors [1], scientists have relied on tumor in vivo models or the integration of tumor in vitro models with in vivo models to circumvent the shortcom- ings in in vitro models. Current integration approaches typically introduce tumor cells to in vivo models as single cell suspensions, multi-layered systems such as biopsies, or embedded in scaffolds such as gels or sponges prior to implantation [2, 3]. Additionally, some investigators add exogenous fac- tors in the culture medium or scaffolds to induce certain functions such as angiogenesis [4] and invasion, that may manifest only in in vivo environments [5]. Single cell suspensions and biopsies may not be ideal tumor systems for bioengineering applications requiring quantitative analysis. This is because, biopsies cut di- rectly from the animal host may not have a homogene- ous cell population, and single cell suspensions lack a uniform and constant shape. In contrast, the symmetric 3D configuration of multi- layered tumor spheroids, a sphere, and the radial de- pendency of their proliferative and metabolic properties, can facilitate the generation of boundary conditions and fixed data points useful in quantitative investigations, such as computational modeling of tumor growth [5]. Tumor spheroids have been used extensively in studies of cancer dynamics both as an in vitro model [7,8,9,10] and combination with an in vivo model [9] because they manifest similar growth and morphological dynamics of solid tumors. They begin with an avascular growth stage where the tumor grows to a certain size in vitro generat- ing a necrotic center. As we demonstrate later in the arti- cle, tumor spheroids can induce angiogenesis and pro-  N. De Magalhães et al. / J. Biomedical Science and Engineering 3 (2010) 20-26 SciRes Copyright © 2010 JBiSE 21 Figure 1. H&E histological section of a 1 mm diameter ACBT glioblastoma spheroid embedded in CAM. Grey area is the CAM; center region in purple denotes the tu- mor spheroid. Dark purple regions along the top mem- brane denote tumor cells invading regions of the CAM; (a) Top view of tumor spheroid and CAM interface of the formalin fixed spheroid inside CAM (mesoderm) after removal from the chicken and embryo prior to histologi- cal processing; (b) Tumor microvasculature as a result of angiogenesis (1,2,3). mote vascular growth when introduced to an in vivo en- vironment with existing vascular network. Biomedical imaging systems ideally require a wide working area, and a steady flat environment for consis- tent analysis. Imaging resolution and light penetration deep into animal tissue can be compromised due to ex- cessive light scattering and absorption from animal tis- sues. Qualitative and quantitative data acquisition may be facilitated with tissue of greater transparency such as the chicken embryo chorioallantoic membrane (CAM). The traditional in-shell CAM model [12], although still useful as an alternative system to animal models for studies of tumor angiogenesis[13] and tumor dynamics [14,15], is not optimal for imaging and biomedical en- gineering investigations due to its restricted and unstable environment. Within the shell environment, the embryo can move freely in the presence of perturbations. Drug injections and imaging studies can be challenging with constant movement of the medium. In addition, the ex- perimental window of the shell model can be very small, restricting access to the entire vessel network and limit- ing the size of the experimental site. Surface tension may cause the surface of the CAM in the shell model to curve. The shell-less CAM version was introduced to address the drawbacks of the traditional shell CAM model [16,17,18]. The shell-less CAM model not only offers a stable and flat environment, it also offers a large ex- perimental area and wider field of view useful for imag- ing and biomedical engineering applications. Unlike current shell-less models, our model is the first model to use three-dimensional spheroids as the tumor system of choice. The three-dimensional spheroids are implanted directly into the CAM, and vascularized spheroids are generated endogenously without the use of growth factors to promote angiogenesis or scaffolds to secure and confine the tumor inside the CAM. This form of vascularization allows the study of the tumorigenic behavior of three dimensional tumors with- out the application of exogenous signals that could oth- erwise interfere with the natural processes of tumors. Tumor spheroids combined with the shell-less CAM model can enhance the capabilities of bioengineering modalities by providing a sophisticated tumor model with excellent imaging properties that can facilitate the studies of the angiogenic switch, and model the onset of tumor progression quickly and more effectively. 2. MATERIALS AND METHODS The in vivo shell-less CAM tumor spheroid model was prepared as follows: Initially, monolayers of ACBT grade IV human glio blastoma were cultured in T-75 culture flasks containing enhanced Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM), supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum, 1% of streptomycin, penicillin, L-glutamine, and non-essential amino acids. The cells were maintained at 37ºC and 8% CO2 in a tissue culture incubator. After reaching 60% confluence, small tumor aggregates started to form. Using the liquid overlay method [7], ACBT suspension aggregates were collected from the flasks and transferred to culture medium filled square Petri-dishes with the bottom covered with 2% agar. Cul- ture medium was changed three times a week. The tumor spheroids derived from ACBT suspension aggregates grew to 1 mm in diameter in approximately 30 days. For consistency, 1 mm3 spheroids were selected from the spheroid colony on the day of implantation. Three days old white fertilized Leghorn chicken eggs (AA Lab Eggs, Inc, Westminster, CA, USA) were disin- fected with 70% alcohol wipes, and incubated in a ven- tilated hatching incubator at 38°C for three hours. After incubation, eggs were removed from the incubator, and under light restricted conditions, egg contents were carefully transferred from the egg shells to a condiment cup. The cups are covered with a breathable polyethy- lene sheet (fisher brand) and returned to the incubator. On day seven of embryonic stage (EA), the cups con- taining the chicken embryos were removed from the incubators. After a small incision was made on the outer membrane of the CAM, one tumor spheroid was im-  N. De Magalhães et al. / J. Biomedical Science and Engineering 3 (2010) 20-26 SciRes Copyright © 2010 JBiSE 22 planted onto the mesoderm of CAM. Chicken embryos were returned to the incubator for 24 hrs. The implanta- tion was assessed after 24 hours, and angiogenesis was assessed 7 days post implantation (EA 14) using a ste- reomicroscope (Olympus, model SZH) coupled to a digital camera (Olympus DP 10). After visual assess- ment, the CAM/spheroid interfaces were fixed with 10% formalin, removed from the CAM, and stored in 10% formalin solution overnight. The samples were processed, embedded in paraffin and cut in 6 µm serial sections. The sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) to distinguish the tumor, tumor microvasculature and CAM environ- ments. 3. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION Microvasculature is observed around the spheroid region in Figure 1(a). The middle H&E stained histological section of the CAM/tumor spheroid interface (largest cross-sectional area of tumor spheroid) shows three dis- tinct microvessels at the center of the spheroid (Figure 1(b)). New tumor regions are observed, as well as inva- sion in adjacent CAM areas. Vascularized tumor spheroids were endogenously generated with this spheroid based shell-less CAM model using spheroids derived from human glioblastoma (U-87 MG and ACBT), human breast cancer (MCF-7), and human pancreatic cancer (BXPC-3) cell lines. En- dogenous tumor induced angiogenesis is evident by the penetration of the blood vessels to the center of the ACBT tumor spheroid as shown in Figure 1(b). New tumor regions on the CAM (grey regions) adjacent to the tumor spheroid (middle purple mass) show the invasive capability of the tumor. Not only is this system adaptable to different types of tumor cell lines to generate vascularized tumor spheroids, it can be used to investigate multiple tumor related processes including, tumor growth, angiogenesis, inva- sion and metastasis. The experimental configuration of this system allows its integration with biomedical engi- neering platforms for more sophisticated analysis of these biological processes. The following section discusses applications of this model in some areas of biomedical research, including therapeutic, computational, and optical imaging studies. 4. APPLICATIONS IN BIOMEDICAL ENGINEERING RESEARCH 4.1. Application in Therapeutic Studies: Photodynamic Therapy The CAM system has been used previously to study the effects of therapeutic drugs, such as chemotherapy drugs and photodynamic therapy (PDT) photosensitizers [19] on tumor cells and microvasculature. The advantage of Figure 2. ALA mediated Photodynamic Therapy (PDT) in vascularized tumor spheroids implanted on the CAM of a chicken embryo. (a) Normal vascularized ACBT glioma sphe- roid pre-PDT; (b) Vascularized ACBT glioma spheroid post- PDT. using this CAM-spheroid model to study therapeutic efficacy is that, multiple spheroids can be implanted on the same system for dosimetry analysis andmulti-param- eter evaluations. In a previous Photodynamic Therapy study, the shell-less CAM-tumor spheroid model was used to ex- amine the effects of combined Amino-levulinic Acid (ALA) mediated PDT on tumor growth and microvascu- lature [9]. Damage to the tumor cells, extracellular ma- trix (ECM) and microvasculature (occluding) after acute ALA-mediated PDT was observed in Figure 2(b). Indi- vidual blood cells are no longer distinct, and microvas- culature lining was no longer visible (Figure 2(b)), com- pared to normal tumor vasculature observed in Figure 2(a). This shows that PDT was effective in causing vas- cular damage inside the tumor and on the CAM. The tumor cell shape and nucleus is no longer round. Previ- ous studies have reported similar findings [19,20]. Addi- tionally, the extracellular matrix (ECM) of the tumor environment was observed to have a rough characteristic after PDT treatment. Standard assays have used tumor cell suspensions embedded in the CAM to investigate the effect of PDT on tumor growth and angiogenesis [5]. Because cells suspensions tend to be more diffuse than spheroids, it is possible that in cell suspension, the PDT effect could be excessive since solid tumors do not appear in nature as cell suspensions. Furthermore, the use of exogenous angiogenic factors to induce angiogenesis may introduce differences in PDT efficacy. This in vivo shell-less CAM – tumor spheroid model would be a great model to con- duct comparative studies since no exogenous factors are used to induce angiogenesis, and the morphology of the spheroid and its natural growth in the CAM represent a  N. De Magalhães et al. / J. Biomedical Science and Engineering 3 (2010) 20-26 SciRes Copyright © 2010 JBiSE 23 Figure 3. (a) 3-D Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT) and (c) Optical Doppler Tomography (ODT) imaging of CAM-spheroid section of a live chicken embryo (Image Acquisition Time ~2 min). (b) This figure shows real time ODT imaging of blood flow in a major blood vessel in the CAM next to the spheroid. The different colors represent the velocity of blood flow. Black color repre- sents zero velocity and red color represents maximum velocity. Velocity increases from black, green, yellow to red. more realistic model of in vivo tumors. The use of this model is not limited to photodynamic therapy. Nanotherapy has been a growing field of invest tigation in recent years. Scientists are interested in de- veloping effective delivery mechanisms for therapeutic drugs of the same nanoscale as their biological targets. Scientists have used the traditional CAM system to test the delivery capabilities and target selectivity of thera- peutic drugs and hydrophobic nanoparticles carrying therapeutic drugs [19] for photodynamic therapy based [21] and chemotherapy based [22] cancer treatments. Nanoparticles for drug delivery and treatment pur- poses could be introduced into the CAM vascular net- work for analysis and validation of its effectiveness to reach the tumor spheroid region penetrate the tumor mi- crovasculature and release the therapeutic drug. When used in conjunction with a color coded marker or visual tag, the nanoparticles can be tracked by means of in vivo imaging systems as they progress from the CAM vascu- lar network to the tumor spheroid microvasculature. As discussed in the following section, Doppler studies [23,24], such as rate of nanoparticle delivery to the target site could also be quickly assessed by coupling our tu- mor system with a Doppler based imaging system. 4.2. Application in Optical Imaging Studies Sophisticated imaging devices with cancer diagnostic implications can be validated and optimized using this fast and simple in vivo shell-less CAM – tumor spheroid model. The large aperture and flat surface of the model could facilitate imaging, system alignment and diagnos- tic experiments. This shell-less CAM tumor spheroid model was used to validate a combined Optical Coher- ence Tomography (OCT) and Optical Doppler tomogra- phy (ODT) system developed by Zhongping Chen et al [23,25,26]. OCT has been used extensively in the clinical arena as an alternative to conventional systems such as MRI and CT to image the morphology of soft tissue [27]. In addi- tion, ODT has been used to investigate and measure flow of blood and other fluids in tissue [24,27,28,29,30]. Both systems can be combined to provide both morphological and functional information of the tissue of interest [24,28]. The structure and morphology of the CAM-spheroid interface (Figure 3(a) and 3(c)), as well as the blood flow in the vessels (Figures 3(b) and 3(c)) were ana- lyzed simultaneously using this combined system. The morphology of CAM – tumor system was suc- cessfully assessed using this combined OCT-ODT sys- tem. The shape of the tumor spheroid as well as of the blood vessels along the surface of the CAM is clearly evident in Figures 3(a) and 3(c). However, any branch- ing of vessels into the tumor spheroid cannot be detected from the OCT and ODT images. In addition, Figure 3(b) shows the real-time imaging of a functional major blood vessel in the CAM with large blood flow in the center, and less blood flow in the periphery. The ODT channel of the system can detect velocity changes based on color mapping, with black color representing zero velocity and red color represent- ing maximum velocity. Thus, velocity increases from black, blue, and green, yellow to red. Figure 3(c) illus- trates the variation of blood velocity along major vessels. Yellow regions depict centers of high velocity, while blue regions depict areas of low velocity. There is a blue region on the major blood vessel adjacent to the tumor spheroid. One can speculate that low blood flow in that region may be an indication of branching of vessels near the tumor causing a reduction of flow in main vessel. Further work is necessary to investigate this phenomena and any impact that tumor induced angiogenesis may have on blood flow in major vessels adjacent to tumor masses. Moreover, future advancements in the technology of the ODT system may allow the direction of blood flow to be detected, leading to the identification of different types of vessels in tissue such as capillaries and veins. 4.3. Application and Integration in In Silico and Computational Studies Mathematical modeling and multi-scale computer simu- lations of tumor dynamics have a promising future as innovative diagnostic tools for treatment of cancer in addition and complementary to experimental and clinical  N. De Magalhães et al. / J. Biomedical Science and Engineering 3 (2010) 20-26 SciRes Copyright © 2010 JBiSE 24 Figure 4. 3-D In-silico simulation of Tumor Spheroid in- duced Angiogenesis: (a) Early time; (b) Later time. The thin curves show vessel sprouts, the thick red curves describe blood-carrying vessels. The inner surface bounds the perine- crotic region. Figure courtesy of Dr. Fang Jin using methods described in [36,39]. investigations [31]. Various mathematical models have been designed to perform in silico (on the computer) experiments or simulations to investigate and predict tumor behavior and response to therapy both in vivo and in vitro [32,33]. These include modeling of tumor growth [34,35,36], invasion [37], angiogenesis and vascular growth [36,38, 39,40], drug delivery [5,41,42] and therapeutic response [43,44]. The in-silico results are compared with experi- mental and histological in vitro and in vivo data to vali- date and optimize the model’s predictions. In addition to providing more insight into the cancer dynamics, the predictive capability of the computer tumor simulator may offer many future clinical applications. To simulate tumor processes, these models require the acquisition of parameters such as tumor and necrotic core sizes before and after angiogenesis, density of blood vessels, speed of vessel migration towards the tumor, and gradients of growth factors involved in an- giogenesis such as VEGF. The predictive capabilities of these models can be improved and optimized with the use of in vivo biological models that represent the dy- namics of realistic tumors. Current computational models often use tumor sphe- roids to integrate in vitro experimental data with vascu- lar tumor growth simulations and vascular extrapolations [36,39]. An example of in silico tumor spheroid inducing angiogenesis is shown in Figure 4. The in vivo shell-less CAM 3-dimensional tumor spheroid model has the po- tential to enhance the capabilities of computational models by providing data for an in vivo and three-di- mensional component representative of solid tumors. Thus, by integrating this data, tumor simulations will reflect more realistic representation of tumor vasculature and behavior. The shell-less CAM tumor spheroid system may be used to acquire the parameters described above and validate computational models because it can yield fast results due to its short experimental period. Furthermore, the transparency of the CAM may facilitate data proc- essing using imaging systems. In addition to the CAM’s flat surface and closed system, the spheroid’s initial symmetrical geometry may facilitate the formulation of equations and boundary conditions that represent the processes such as growth and angiogenesis that govern tumor proliferation. Thus, quantitative information can be extracted from tissue samples of the shell-less CAM tumor spheroid system. This model would be easily adaptable to existing mathematical models already using the tumor spheroid as an in vitro system, as the spheroid is simply being transferred to an in vivo platform (the CAM), enabling the incorporation of the in vivo compo- nent to existing mathematical principles. Once these models are optimized they have the poten- tial to be used to predict the aggressiveness of a patient’s tumor. In addition, they could also predict a patient’s tumor response prior to treatment. That is, the in silico model could be used as a diag- nostic tool to recommend the most effective individual- ized treatment based on the patient’s prognosis. This can prevent the development of resistance to treatment by eliminating trial and error treatment sampling. Other advantages of the in silico model include providing fast and non-invasive diagnosis thus minimizing the dis- comfort to the patient, and improving overall quality of life. Finally, while the application of in-silico models in cancer therapy require improved understanding of cancer behavior and mechanisms, their versatility allows opti- mization and calibration of parameters to match with new developments and knowledge of cancer dynamics. 5. CONCLUSIONS The in vivo 3-dimensional tumor spheroid based shell- less CAM model presented in this article is a new, at- tractive and practical system to study multiple mecha- nisms of tumor biology, including tumor growth, inva- sion, and angiogenesis. In addition, this system has a vast and dynamic application in many biomedical and bioengineering studies including drug discovery, nano- particle delivery, therapeutic efficacy, cancer diagnostic imaging device development and validation, and mathematical and computer simulations of cancer dy- namics [45]. The development of this system successfully created vascularized spheroids in the CAM in the absence of exogenous factors four days after implantation. Due to the system’s analogous representation of the microenvi- ronment found in vivo solid tumors, this model can be used as an alternative or complement to animal models, and the research findings can provide preliminary im- plications to clinical studies. 6. ACKNOWLEDGMENT This article was made possible by the tremendous generosity, expertise and mentorship of the honorable Ms. Li-Huei Liaw. We acknowledge  N. De Magalhães et al. / J. Biomedical Science and Engineering 3 (2010) 20-26 SciRes Copyright © 2010 JBiSE 25 Linda Li and Angela Giogys for the valuable contributions during the data processing stage. We also extend our gratitude to Dr. Tromberg for the use of the Beckman Laser Institute facilities. We further thank Dr. Fang Jin for his assistance with the in silico vascular tumor shown in Figure 4. Financial support for this project was provided by the NIH F31 Grants CA12371-01 and CA12371-02, and the Merck-UNCF pre-doctoral fell- owship, and NIH grant number EB-00293. REFERENCES [1] Zietarska, M. et al. (2007) Molecular description of a 3D in vitro model for the study of epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC). Mol Carcinog, 46(10), 872-85. [2] Nakatsu, M.N. and Hughes, C.C. (2008) An optimized three-dimensional in vitro model for the analysis of angiogenesis. Methods Enzymol, 443, 65-82. [3] Claudia F. et al (2007) Engineering tumors with 3D scaffolds. Nature Methods, 4 (10): 855-860. [4] Szpaderska, A.M. and DiPietro, L.A. (2003) In vitro matrigel angiogenesis model. Methods Mol Med, 78, 311-315. [5] Duong, H.S. et al. (2005) A novel 3-dimensional culture system as an in vitro model for studying oral cancer cell invasion. Int J Exp Pathol, 86(6), 365-74. [6] Hammer-Wilson, M.J., Cao, D., Kimel, S. and Berns, M.W. (2002) Photodynamic parameters in the chick chorioallantoic membrane (CAM) bioassay for photo- sensitizers and administered intraperitoneally (IP) into the chick embryo. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci., 1, 721-728. [7] Santini, M. and Rainaldi, G. (1999) Three-dimensional spheroid model in tumor biology. Pathobiology, 67, 148- 157. [8] Liang, Y., Pjesivac-Grbovic, J., Cantrell, C. and Freyer, J.P. (2005) A multiscale model for avascular tumor growth. Biophysical Journal, 89, 3884-3894. [9] Madsen, S.J, Sun, C.H., Tromberg, B.J., Wallace, V.P. and Hirschberg, H. (2000) Photodynamic therapy of human glioma spheroids using 5-aminolevulinic acid. Photochemistry and Photobiology, 72, 128-134. [10] Reyes-Aldasoro, C.C. et al. (2008) Estimation of apparent tumor vascular permeability from multiphoton fluorescence microscopic images of P22 rat sarcomas in vivo. Microcirculation, 15(1), 65-79. [11] De Magalhães, N., Liaw, L.H.L., Li, L., Liogys, A., Madsen, S.J., Hirschberg, H. and Tromberg, B.J. (2006) Investigating the effects of combined photodynamic and anti-angiogenic therapies using a three-dimensional in vivo brain tumor system. SPIE Proceedings on Photonic Therapeutics and Diagnostics, 6078, 503-508. [12] Knighton, D. et al. (1975) Study of avascular and vascular phases of tumor growth in chick embryo. Clinical Research, 23(4), 557. [13] Ishiwata, I. et al. (1999) Tumor angiogenesis factors produced by cancer cells. Hum Cell, 12(1), 37-46. [14] Ribatti, D., Nico, B., Vacca, A., Roncali, L., Burri, P. and Djonov, V. (2001) Chorioallantoic membrane capillary bed: a useful target for studying angiogenesis and anti-angiogenesis in vivo. The Anatomical Record, 264, 317-324. [15] Stewart, J. (1999) Calculus, Brooks/Cole Publishing Company, 6, 378. [16] Dunn, B.E. (1974) Technique of shell-less culture of the 72-hour avian embryo. Poult Sci, 53(1), 409-412. [17] Jakobson, A.M., Hahnenberger, R. and Magnusson, A. (1989) A simple method for shell-less cultivation of chick embryos. Pharmacol Toxicol, 64(2), 193-195. [18] Ono, T. (2000) Exo ovo culture of avian embryos. Methods Mol Biol, 135, 39-46. [19] Vargas, A., Zeisser-Labouèbe, M., Lange, N., Gurny, R., Delie, F. (2007) The chick embryo and its chorioallantoic membrane (CAM) for the in vivo evaluation of drug delivery systems. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews, 59(11), 1162-1176. [20] Hammer-Wilson, M.J., Akian, L., Espinoza, J., Kimel, S. and Berns, M.W. (1999) Photodynamic parameters in the chick chorioallantoic membrane (CAM) bioassay for topically applied photosensitizers. J. Photochem. Photobiol, 53, 44-52. [21] Vargas, A., Eid, M., Fanchaouy, M., Gurny, R., Delie, F. (2008) In vivo photodynamic activity of photosensitizer- loaded nanoparticles: formulation properties, administra- tion parameters and biological issues involved in PDT outcome. European Journal of Pharmaceutics and Bio- pharmaceutics, 69, 43-53. [22] Imtiaz, A. et al (2009) Introducing Nanochemo- prevention as a Novel approach for cancer control: proof of principle with green tea polyphenol epigallocatechin- 3-gallate. Cancer Res, 69(5), 1712-1716. [23] Chen, Z. (2004) Optical doppler tomography. In Handbook of Coherent Domain Optical Methods, Tuchin V.V. (ed), Kluwer Academic Publishers, Boston, 2, 315- 342. [24] Ding, Z, Zhao, Y, Ren, H, Nelson, J. and Chen, Z. (2002) Real-time phase-resolved optical coherence tomography and optical Doppler tomography. Optics Express, 10: 236-245. [25] Chen, Z., Milner, T., Srinivas, S., Malekafzali, A., Wang, X., Van Gemert, M. and Nelson, J. (1997) Imaging in vivo blood flow velocity using optical doppler tomo- graphy. Opt. Lett., 22, 1119-1121. [26] Chen, Z. Milner and T.E et al. (2000) Noninvasive imaging of in vivo blood flow velocity using optical doppler tomography. Optical Low Coherence Reflec- tometry and Tomography, SPIE Milestone Series Book of Selected Papers. [27] Baumal, C.R. (1999) Clinical applications of optical coherence tomography. Curr Opin Ophthalmol, 10(3), 182-188. [28] Donald, I., MacVicar, J. and Brown, T.G. (1958) Inves- tigation of abdominal masses by pulsed ultrasound. Lancet, 1(7032), 1188-1195. [29] Kehlet-Barton, J. et al. (1999) Three-dimensional recon- struction of blood vessels from in vivo color Doppler optical coherence tomography images. Dermatology, 198(4), 355-361. [30] Szkulmowska, A. et al. (2008) Phase-resolved doppler optical coherence tomography--limitations and improve- ments. Opt Lett, 33(13), 1425-1427.  N. De Magalhães et al. / J. Biomedical Science and Engineering 3 (2010) 20-26 SciRes Copyright © 2010 26 JBiSE [31] Gomez-Lopez, G. and Valencia, A. (2008) Bioin- formatics and cancer research: building bridges for translational research. Clin Transl Oncol, 10(2), 85-95. [32] Roose, T., Chapman, S.J. and Maini, P.K. (2007) Mathe- matical models of avascular tumor growth, SIAM Review, 49, 179-208. [33] Cristini Cristini, V., Frieboes, H.B., Li, X., Lowengrub, J. S., Macklin, P., Sanga, S., Wise, S.M. and Zheng, X. (2008) Nonlinear modeling and simulation of tumor growth. In Modeling and simulation in science, engineering and technology, ed. Bellomo, N., Chaplain, M.A.J., De Angeles, E., Birkaeuser, Boston. [34] Macklin, P. and Lowengrub, J. (2007) Nonlinear simulation of the effect of microenvironment on tumor growth. J Theor Biol, 245(4), 677-704. [35] Wise, S.M., Lowengrub, J.S., Frieboes, H.B., and Cristini, V. (2008) Three-dimensional multispecies nonlinear tumor growth—I Model and numerical method. J. Theor. Biol., 253, 524-543. [36] Bearer, E S., Lowengrub, J S., Frieboes, H.B., Chuang, Y.L., Jin, F., Wise, S.M., Ferrari, M., Agus, D.B., Cristini, V. (2009) Multiparameter computational modeling of tumor invasion. Cancer Res., 69, 4493- 4501. [37] Cristini, V., Li, X., Lowengrub, J.S. and Wise, S.M. (2009), Nonlinear simulations of solid tumor growth using a mixture model: invasion and branching. J Math Biol, 58, 723-63. [38] Mantzaris, N.V, Steve, S. and Othmer, H.G. (2004) Mathematical modeling of tumor-induced angiogenesis. J. Math. Biol., 49, 111-187. [39] Frieboes, H.B. et al. (2007) Computer simulation of glioma growth and morphology. Neuroimage, 37 (Suppl 1), 59-70. [40] Macklin, P., McDougall, S., Anderson, A.R.A., Chaplain, M.A.J., Cristini, V. and Lowengrub, J.S. (2009) Multiscale modeling and nonlinear simulation of vascular tumor growth. J. Math. Biol., 58, 765-798. [41] Sinek, J.P., Sanga, S., Zheng, X., Frieboes, H.B., Ferrari, M. and Cristini, V. (2009) Predicting drug pharmaco- kinetics and effect in vascularized tumors using computer simulation. J. Math Biol, 58, 485-510 [42] Frieboes, H.B., et al. (2006) An integrated compu- tational/experimental model of tumor invasion. Cancer Res, 66(3), 1597-604. [43] Madsen, S.J., Sun, C.H., Tromberg, B.J., Cristini, V., De Magalhães, N. and Hirschberg, H. (2006) Multicell tumor spheroids in photodynamic therapy. Lasers Surg Med, 38(5), 555-564. [44] Sinek, J. et al (2004) Two-dimensional chemotherapy simulations demonstrate fundamental transport and tumor response limitations involving nanoparticles. Biomed Microdevices, 6(4), 297-309. [45] Herzenberg, L. et al. (2004) American cancer society. Clinical Oncology (Blackwell Publishing), 254-260.

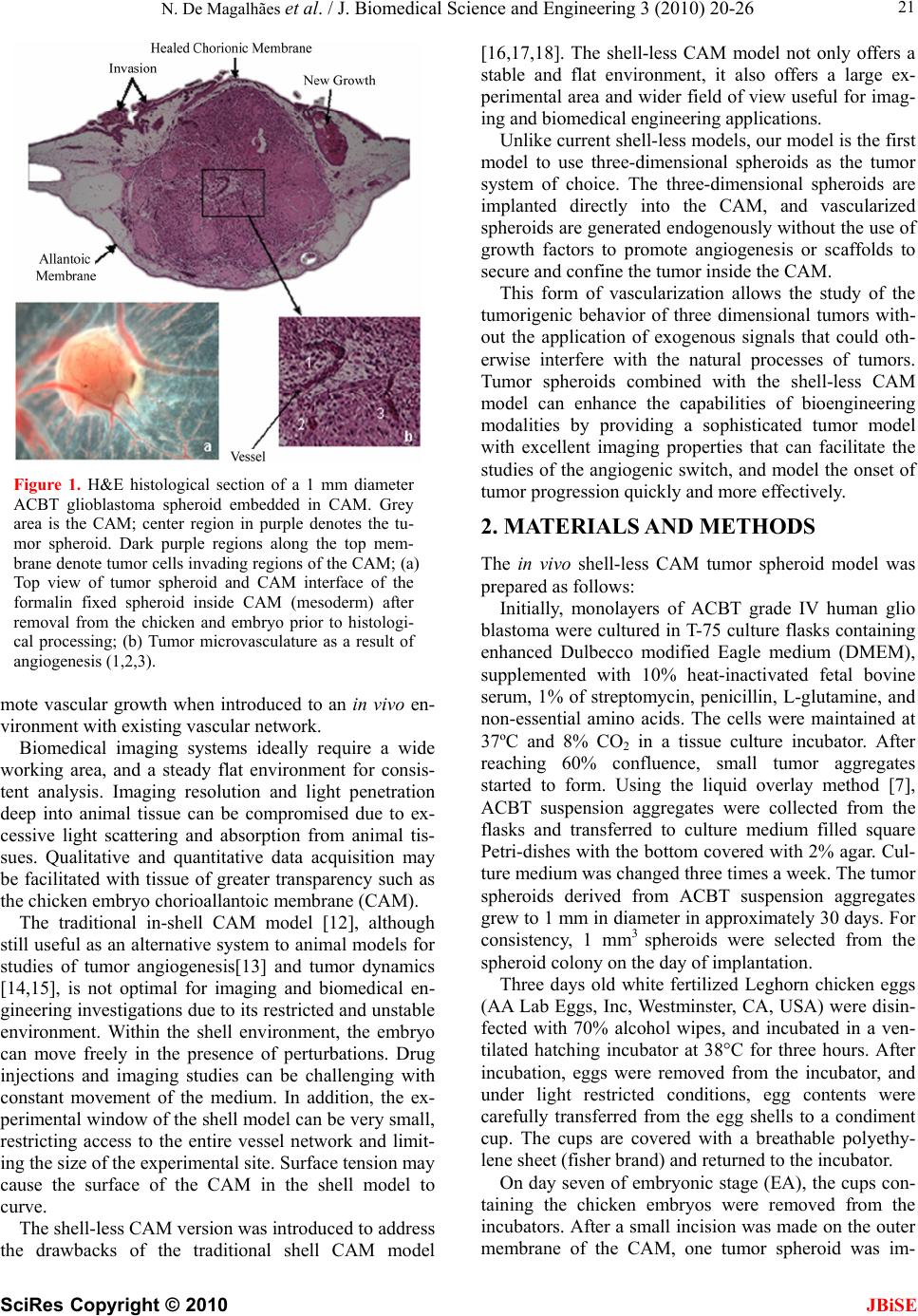

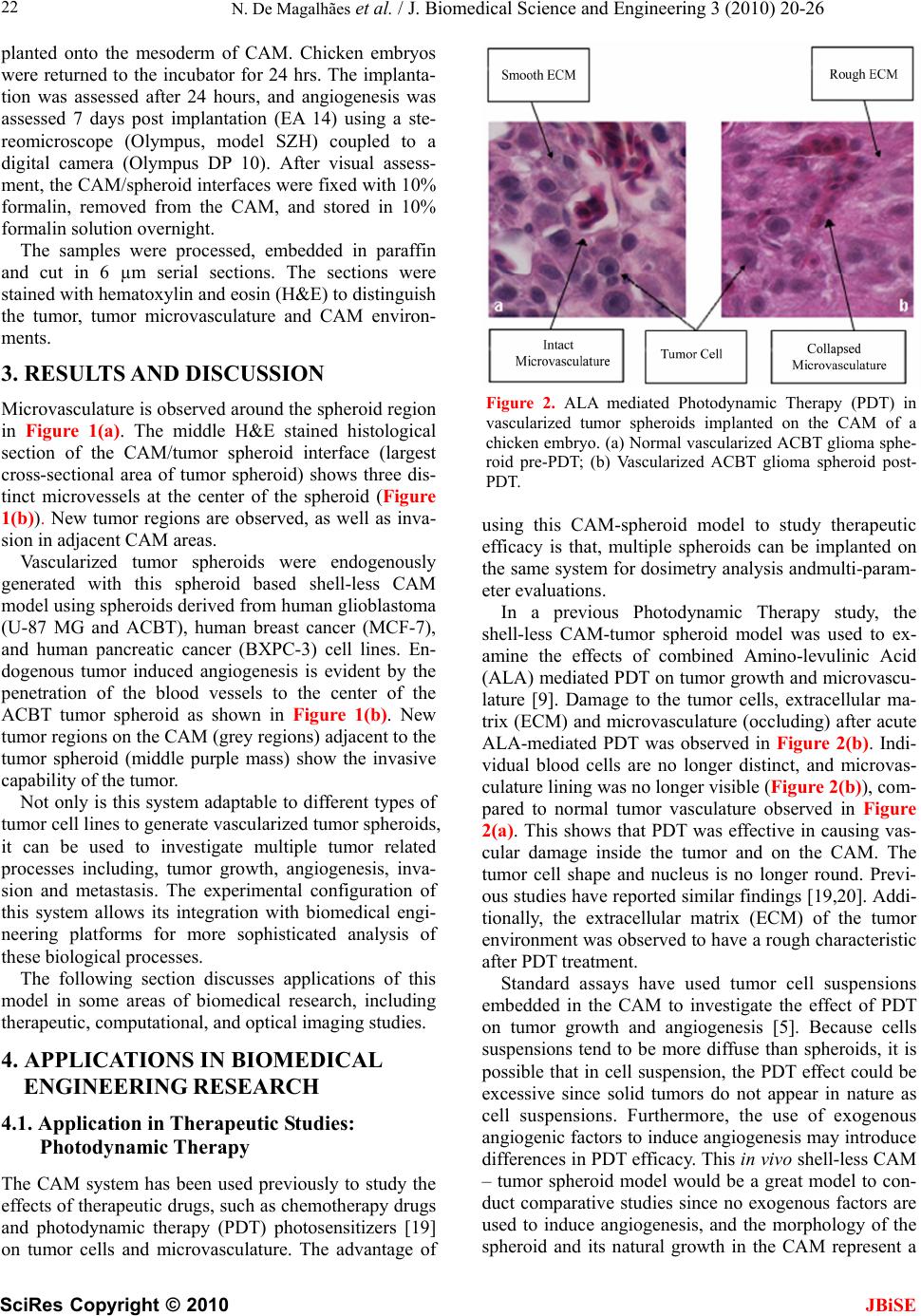

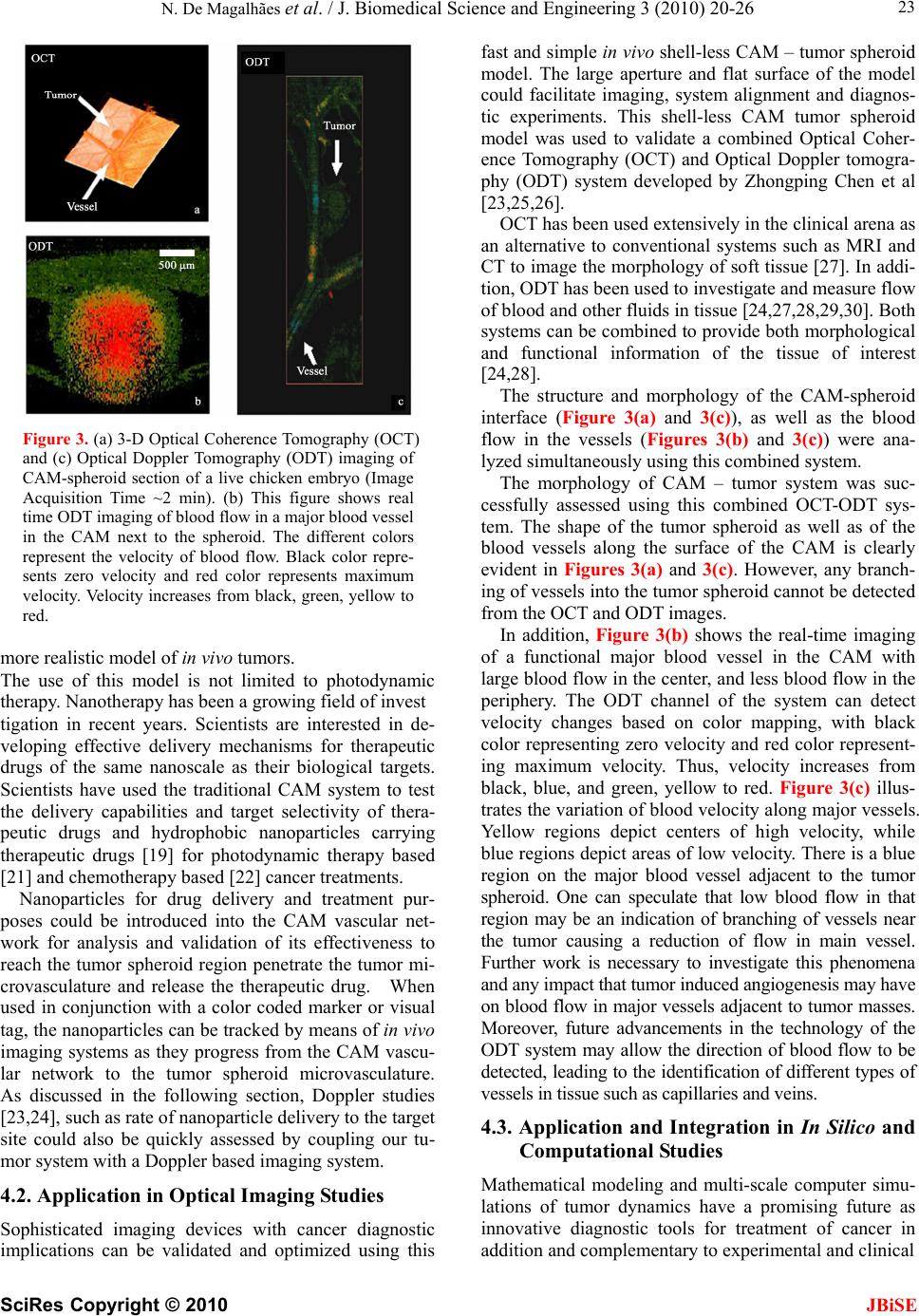

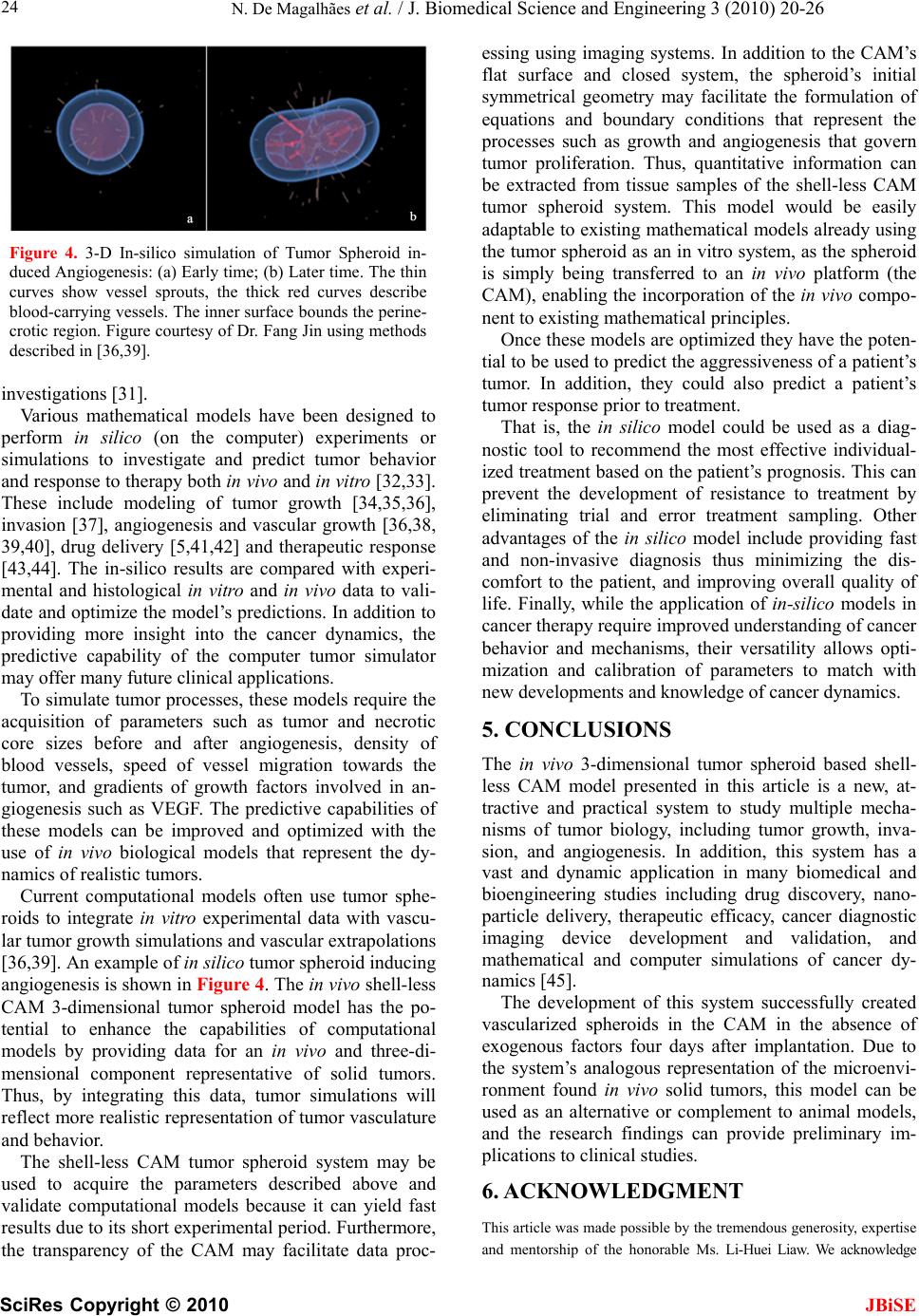

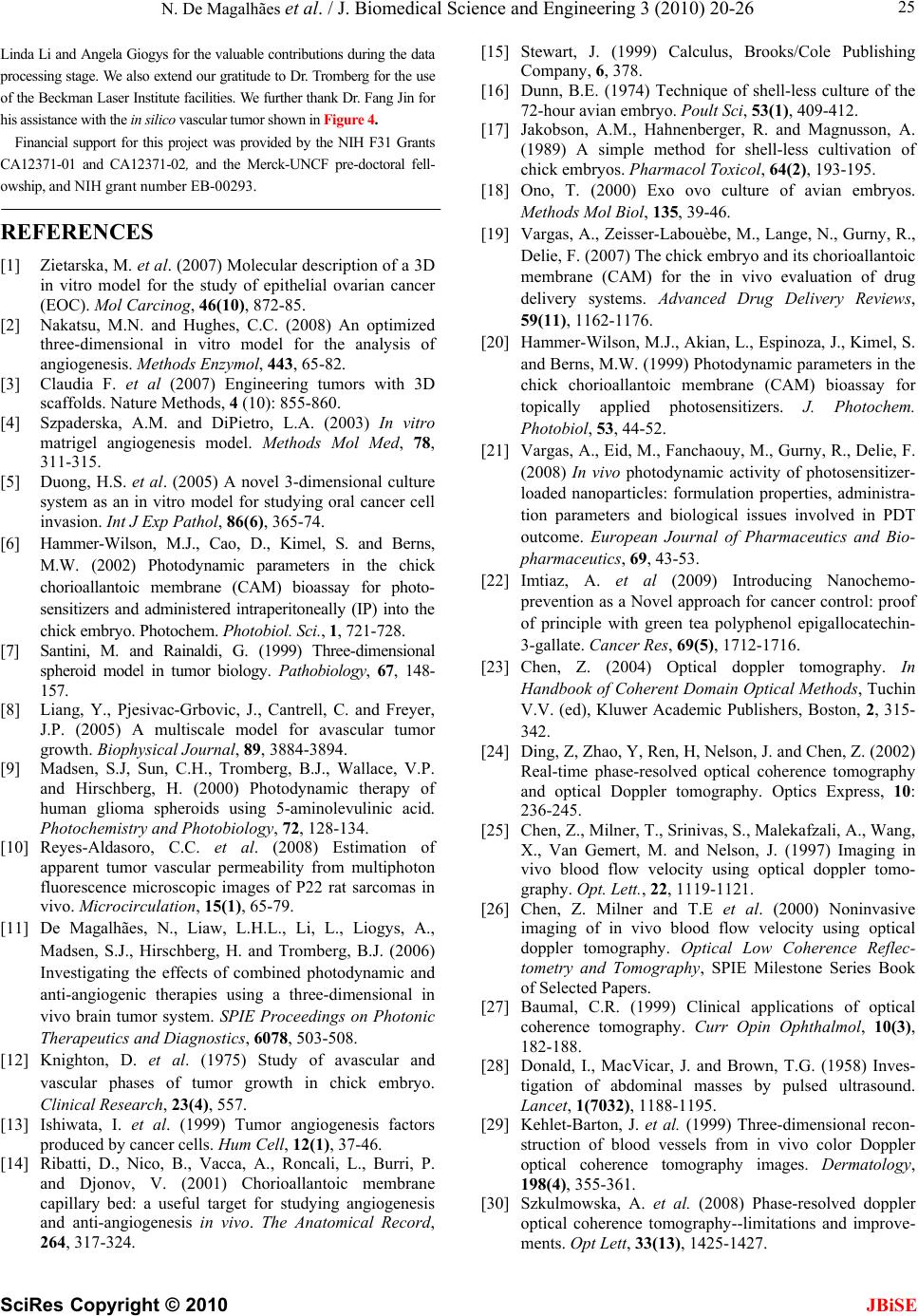

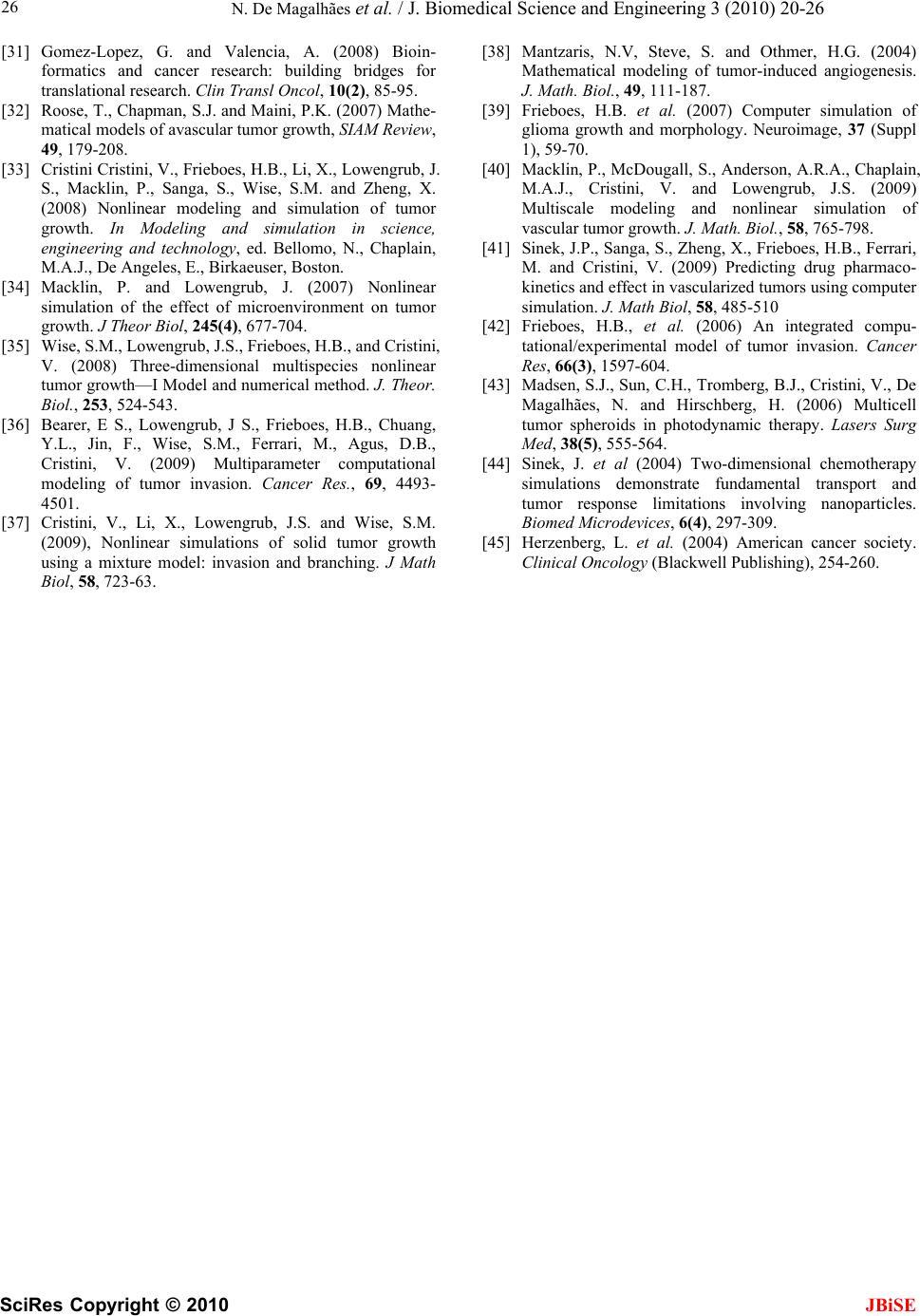

|