Paper Menu >>

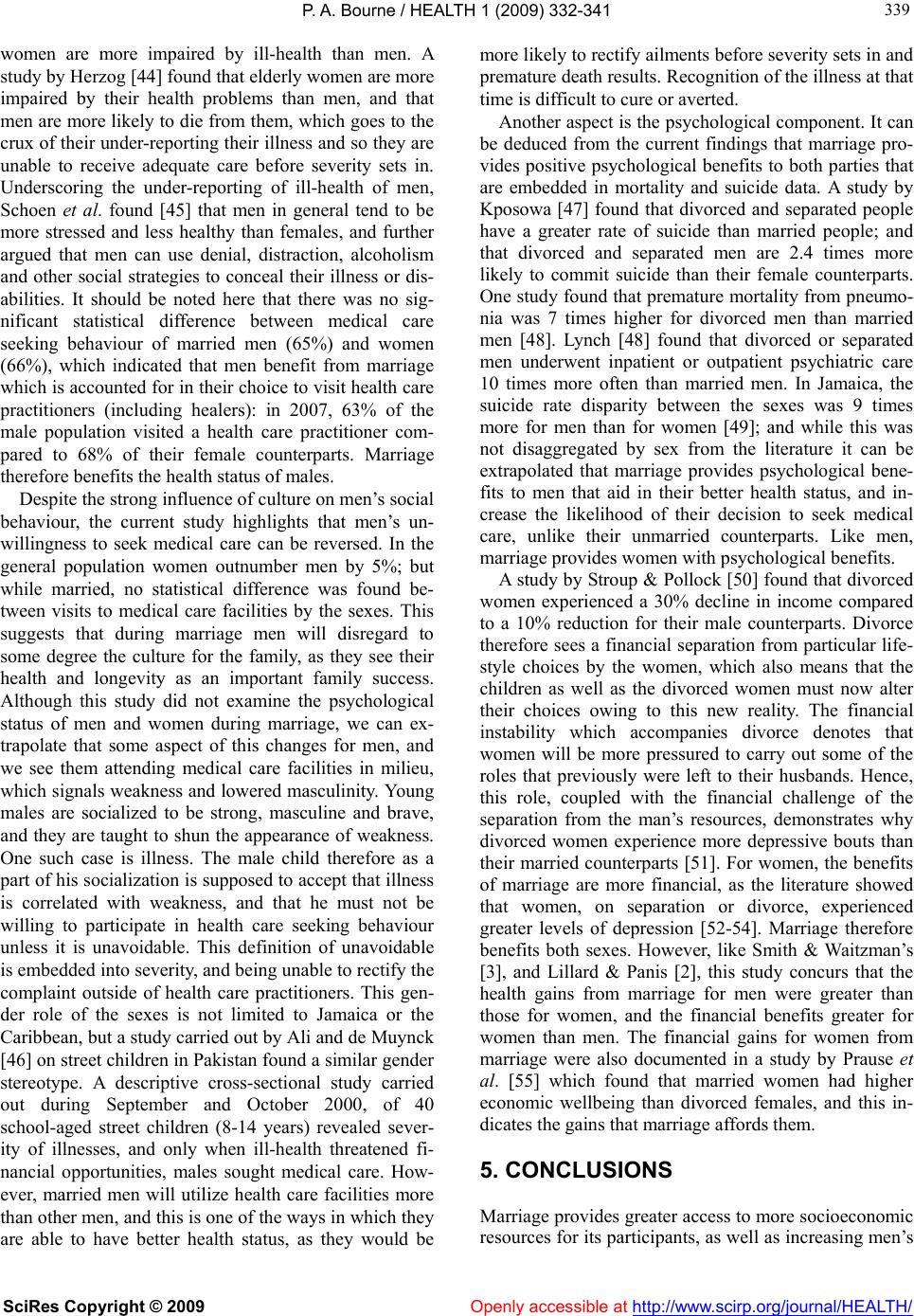

Journal Menu >>

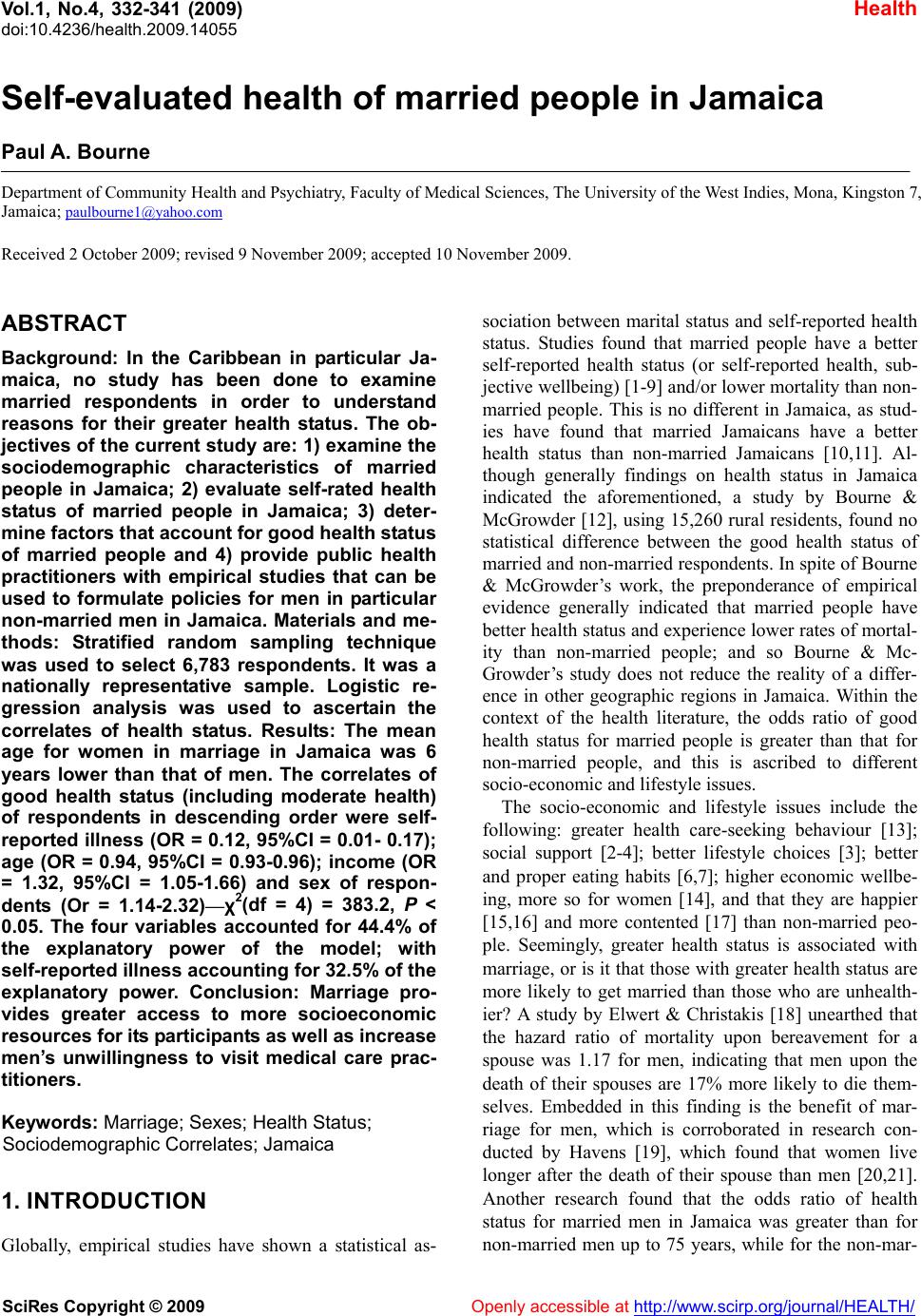

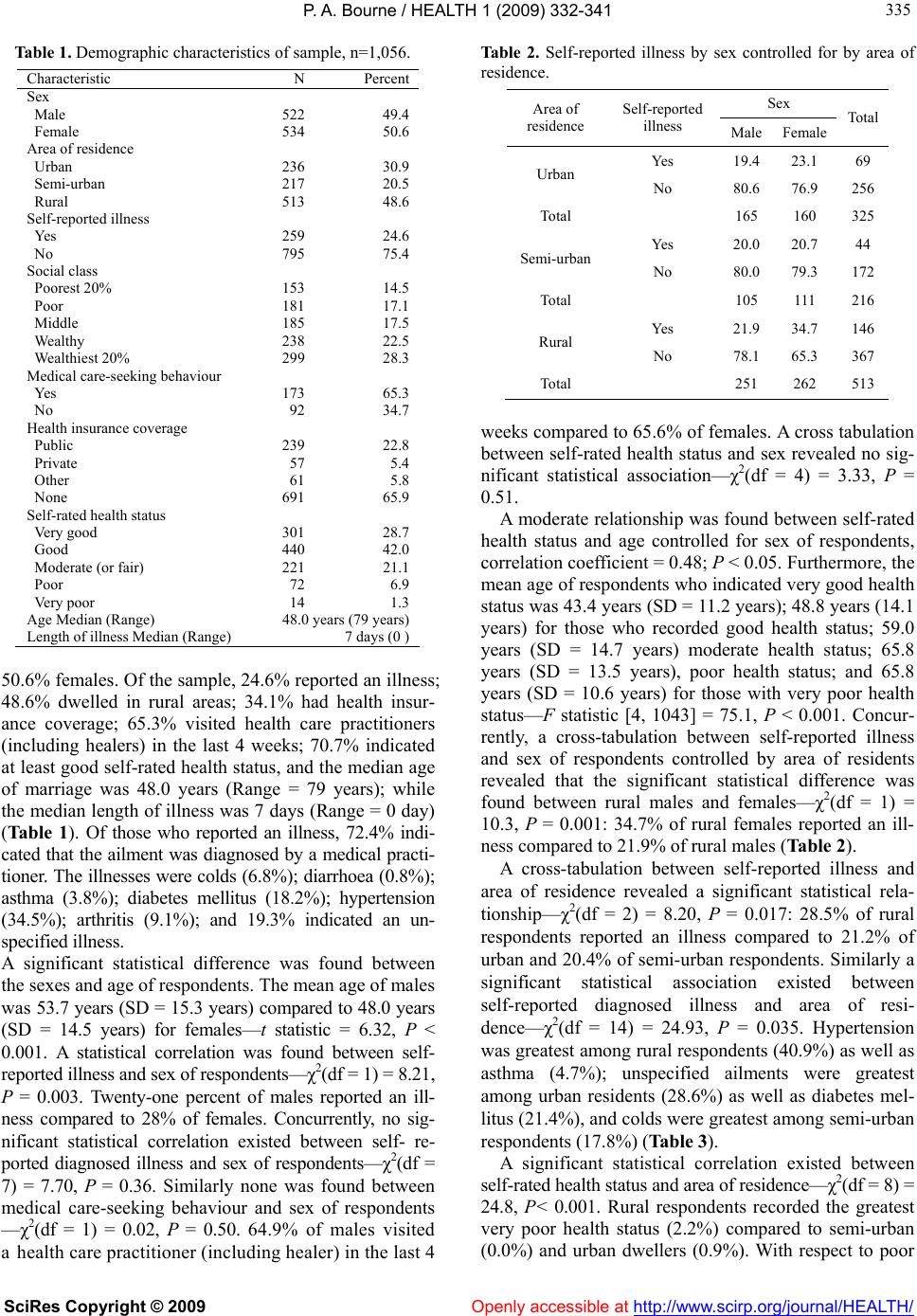

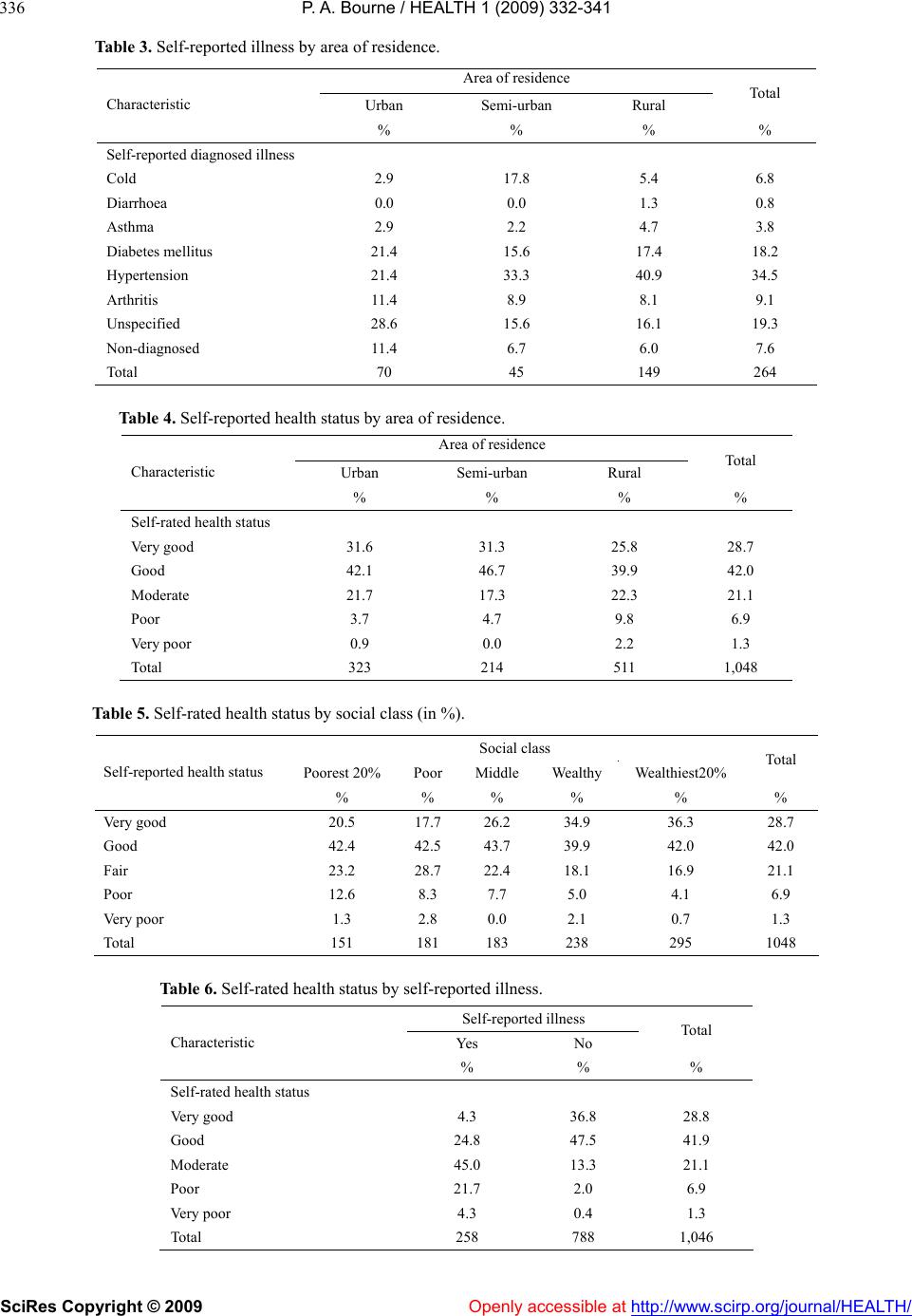

Vol.1, No.4, 332-341 (2009) doi:10.4236/health.2009.14055 SciRes Copyright © 2009 Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ Health Self-evaluated health of married people in Jamaica Paul A. Bourne Department of Community Health and Psychiatry, Faculty of Medical Sciences, The University of the West Indies, Mona, Kingston 7, Jamaica; paulbourne1@yahoo.com Received 2 October 2009; revised 9 November 2009; accepted 10 November 2009. ABSTRACT Background: In the Caribbean in particular Ja- maica, no study has been done to examine married respondents in order to understand reasons for their greater health status. The ob- jectives of the current study are: 1) examine the sociodemographic characteristics of married people in Jamaica; 2) evaluate self-rated health status of married people in Jamaica; 3) deter- mine factors that account for good health status of married people and 4) provide public health practitioners with empirical studies that can be used to formulate policies for men in particular non-married men in Jamaica. Materials and me- thods: Stratified random sampling technique was used to select 6,783 respondents. It was a nationally representative sample. Logistic re- gression analysis was used to ascertain the correlates of health status. Results: The mean age for women in marriage in Jamaica was 6 years lower than that of men. The correlates of good health status (including moderate health) of respondents in descending order were self- reported illness (OR = 0.12, 95%CI = 0.01- 0.17); age (OR = 0.94, 95%CI = 0.93-0.96); income (OR = 1.32, 95%CI = 1.05-1.66) and sex of respon- dents (Or = 1.14-2.32)—χ2(df = 4) = 383.2, P < 0.05. The four variables accounted for 44.4% of the explanatory power of the model; with self-reported illness accounting for 32.5% of the explanatory power. Conclusion: Marriage pro- vides greater access to more socioeconomic resources for its participants as well as increase men’s unwillingness to visit medical care prac- titioners. Keywords: Marriage; Sexes; Health Status; Sociodemographic Correlates; Jamaica 1. INTRODUCTION Globally, empirical studies have shown a statistical as- sociation between marital status and self-reported health status. Studies found that married people have a better self-reported health status (or self-reported health, sub- jective wellbeing) [1-9] and/or lower mortality than non- married people. This is no different in Jamaica, as stud- ies have found that married Jamaicans have a better health status than non-married Jamaicans [10,11]. Al- though generally findings on health status in Jamaica indicated the aforementioned, a study by Bourne & McGrowder [12], using 15,260 rural residents, found no statistical difference between the good health status of married and non-married respondents. In spite of Bourne & McGrowder’s work, the preponderance of empirical evidence generally indicated that married people have better health status and experience lower rates of mortal- ity than non-married people; and so Bourne & Mc- Growder’s study does not reduce the reality of a differ- ence in other geographic regions in Jamaica. Within the context of the health literature, the odds ratio of good health status for married people is greater than that for non-married people, and this is ascribed to different socio-economic and lifestyle issues. The socio-economic and lifestyle issues include the following: greater health care-seeking behaviour [13]; social support [2-4]; better lifestyle choices [3]; better and proper eating habits [6,7]; higher economic wellbe- ing, more so for women [14], and that they are happier [15,16] and more contented [17] than non-married peo- ple. Seemingly, greater health status is associated with marriage, or is it that those with greater health status are more likely to get married than those who are unhealth- ier? A study by Elwert & Christakis [18] unearthed that the hazard ratio of mortality upon bereavement for a spouse was 1.17 for men, indicating that men upon the death of their spouses are 17% more likely to die them- selves. Embedded in this finding is the benefit of mar- riage for men, which is corroborated in research con- ducted by Havens [19], which found that women live longer after the death of their spouse than men [20,21]. Another research found that the odds ratio of health status for married men in Jamaica was greater than for non-married men up to 75 years, while for the non-mar-  P. A. Bourne / HEALTH 1 (2009) 332-341 SciRes Copyright © 2009 Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 333 333 ried women up to 75 years the odds ratio was greater than that for married women. The converse was the case post 75 years, with the odds of good health status for women being significantly more than for men [22]. In Jamaica for 2007, life expectancy at birth for men was 69 years and 74 years for women [23], indicating that over the life span of the average Jamaican man, marriage will provide him with greater health status than if he were not married. Embedded in that finding is the fact that mortality is greater for men than women, which means that many men will be hospitalized before death. One study found that for an elderly couple, on the hos- pitalization of one, mortality rates increased for the other, and that this was even greater for men than for women [24]. The literature has provided a partial understanding of the explanation for the better health status and/or low- ered mortality ratios of married over non-married people. While answering some issues, a number of other issues are still unresolved from the literature. These unresolved issues include 1) whether married people are healthier because those who are likely to become married are healthier, 2) whether men benefit more from marriage than women, 3) whether marriage is the explanation for better self-rated health (subjective wellbeing) and 4) whether there are some protective effects of marriage. With the literature providing some understanding of the disparity in the general health status of married over non-married people, this still does not reduce the unre- solved issues, and can we use a wholesale sociological explanation provided by the developed nations with dif- ferent socialization, customs, practices, sociopolitical milieu and economic base, or even similar developing nations experiences, for an understanding of married people in Jamaica? Concurrently, can we use the general literature to formulate policies for an understanding of married people in Jamaica? One of the questions that was previously asked has been addressed in a longitudi- nal study that found that happier singles were more willing to get married [25], suggesting that marriage attracts singles who have greater subjective wellbeing, and this accounts for some degree of greater odds ratios of married people being healthier than unmarried people. A study among married and non-married men found that mortality was greater for the latter than for the former [26]; and this was also the case among women [27]. An understanding of other societies’ experiences un- doubtedly aids in fashioning a framework for an under- standing of what takes places in Jamaica. However, it cannot be relied upon as the sole explanation for hap- penings in Jamaica. One of the goals of public health policy formulation is its reliance on empirical research, in guiding decisions on how to operate because there is an understanding of the issue at hand. All societies, while being governed by some fundamental similarities, have dissimilarities which must be understood in order to prescribe appropriate measures to address those con- cerns embedded within the particular society. An exten- sive research of the literature found no study that has sought to examine the rationale behind the fact that mar- ried people record greater health status, in particular the men, as an approach to understanding how non-married men’s health status can be improved, and how general health status can be increased in Jamaica. Therefore public health policies have been structured around the literature and studies in other geopolitical zones; al- though those societies have different cultural practices, customs and jurisprudence from that found in Jamaica. It is within this limitation that the current study emerged, to provide an explanation for what constitute the health status of married Jamaicans, in order to guide policy formulation and framework in this society. The objec- tives of the current study are 1) to examine the sociode- mographic characteristics of married people in Jamaica, 2) to evaluate self-rated health status of married people in Jamaica, 3) to determine the factors that account for the good health status of married people and 4) to pro- vide public health practitioners with empirical studies that can be used to formulate policies for men in par- ticular non-married men in Jamaica. 2. MATERIALS AND METHODS Secondary cross-sectional survey data were collected jointly by the Planning Institute of Jamaica (PIOJ) and the Statistical Institute of Jamaica (STATIN) between May and August 2007. The survey is called the Jamaica Survey of Living Conditions (JSLC), and it was primar- ily collected by the aforementioned institutions as policy assessments for programmes and policies instituted by the government of the country. The JSLC began in 1988, and it has been an annual survey since then. It is stan- dard practice that the JSLC’s sample be a proportion (i.e. one third) of the Labour Force Survey (LFC). The last JSLC was conducted in 2007 with the sample being 6,783 respondents. Of the sample of respondents, 15.7% (n = 1,056 respondents) were used for this study. The only criterion for selection was being married. Stratified random sampling was used to randomly select a nationally representative sample for the survey. The design was a two-stage stratified random sample with a Primary Sampling Unit (PSU) and a selection of dwell- ings from the primary units. The PSU is an Enumeration District (ED), which constitutes a minimum of 100 resi- dences in rural areas and 150 in urban areas. An ED is an independent geographic unit that shares a common boundary. This means that the country was grouped into strata of equal size based on dwellings (EDs). Based on the PSUs, a listing of all the dwellings was made, and this became the sampling frame from which a Master  P. A. Bourne / HEALTH 1 (2009) 332-341 SciRes Copyright © 2009 Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 334 Sample of dwellings was compiled, which in turn pro- vided the sampling frame for the labour force. A total of 620 households were interviewed from urban areas; 439 from semi-urban areas and 935 from rural areas, which constituted 6,783 respondents. One third of the Labour Force Survey (i.e. LFS) was selected for the JSLC. The sample was weighted to reflect the population of the nation. The non-response rate for the survey was 27.7%. 2.1. Data Collection The JSLC is a modification of the World Bank’s Living Standards Measurement Study (LSMS) household survey [22]. The instrument was a questionnaire. Face-to-face interviews over the aforementioned period were used to collect the data. A structure questionnaire was used, and interviewers were trained and subsequently deployed to collect the data. The questions covered demographic cha- racteristics, household consumption, health, education, housing, social welfare and related programmes, and in- ventory of durable goods. In 2007, a question on health status was included in the normal health conditions: length of illness, health insurance coverage, health care- seeking behaviour, medical expenditure, typology of health care utilization and immunization coverage of children. 2.2. Statistical Analysis Data were stored, retrieved and analyzed using SPSS-PC for Windows version 16.0. Descriptive statistics were used to provide background information on the sample. Chi-square analyses were used to examine the associa- tion between non-metric variables for area of residence and gender of respondents. Analysis of variance and t-test were also used to examine bivariate association. Logistic regression analyses examined the relationship between good health status and some socio-demographic, economic and biological variables. Forward stepwise logistic regression was used to build the model of good self-reported health status for the current study. The correlation matrix was examined in order to as- certain if autocorrelation and/or multicollinearity existed between variables. Based on Cohen and Holliday [28] correlation can be low (weak)—from 0 to 0.39, moder- ate—0.4-0.69, and strong—0.7-1.0. This was used to exclude (or allow) a variable in the model. Any correla- tion that had at least moderate was excluded from the model in order to reduce multicollinearity and/or auto- correlation between or among the independent variables [29-35]. Another approach in addressing and/or reducing autocorrelation is that all variables identified from the literature review were included in the model, with the exception of those in which the percentage of missing cases was in excess of 30%. Odds Ratios (OR) were used for the interpretation of each significant variable. 2.3. Model Many factors are correlated with health status, and so the best statistical technique is multivariate analysis [36-38] and not bivariate technique. In keeping with the multi-nature of health status, the current study will use multivariate analysis which is captured in Equation 1 Ht=f(Ai, Gi, HHi, ARi, lnY, EDi, MRi, Si, ∑MCt, SRIi, εi) (1) where Ht (i.e. self-rated good current health status in time t) is a function of age of respondents Ai; sex of in- dividual i, Gi; household head of individual i, HHi; area of residence, ARi; logged income, lnC; Education level of individual i, EDi; marital status of person i, MRi; so- cial class of person i, Si; summation of medical expen- diture of individual i in time period t, MCt; self-reported illness, SRIi, and an error term (i.e. residual error). 2.4. Measures An explanation of some of the variables in the model is provided here. Self-reported illness status is a dummy variable, where 1 = reporting an ailment or dysfunction or illness in the last 4 weeks, which was the survey pe- riod; 0 = if there were no self-reported ailments, injuries or illnesses. While self-reported ill-health is not an ideal indicator of actual health conditions because people may underreport, it is still an accurate proxy of ill-health and mortality [39,40]. Health status is a binary measure where 1 = moderate to excellent health; 0 = otherwise, which is determined from “Generally, how do you feel about your health”? Answers to this question are on a Likert scale ranging from excellent to poor. Studies have shown that self-rated health status can be dichotomized into good and poor health [39,41]; but Bourne [22] and Finnas et al. [41] noted that there are issues surrounding this approach. Bourne [22] opined that the dichotomiza- tion of health status for females is acceptable; however there are some challenges when this is done for males. Both Bourne and Finnas et al. found that the inclusion of moderate health status in poor self-reported health status is not best; and this explains the rationale for the inclu- sion of moderate health into good health status for this study. Medical care-seeking behaviour was taken from the question “Has a health care practitioner, healer, or pharmacist been visited in the last 4 weeks?” with there being two options—Yes or No. Medical care-seeking behaviour therefore was coded as a binary measure where 1 = Yes and 0 = Otherwise. 3. RESULTS 3.1. Demographic Characteristics of Sample and Bivariate Analyses The sample was 1,056 respondents: 49.4% males and  P. A. Bourne / HEALTH 1 (2009) 332-341 SciRes Copyright © 2009 http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/Openly accessible at 335 335 Table 1. Demographic characteristics of sample, n=1,056. Characteristic N Percent Sex Male 522 49.4 Female 534 50.6 Area of residence Urban 236 30.9 Semi-urban 217 20.5 Rural 513 48.6 Self-reported illness Yes 259 24.6 No 795 75.4 Social class Poorest 20% 153 14.5 Poor 181 17.1 Middle 185 17.5 Wealthy 238 22.5 Wealthiest 20% 299 28.3 Medical care-seeking behaviour Yes 173 65.3 No 92 34.7 Health insurance coverage Public 239 22.8 Private 57 5.4 Other 61 5.8 None 691 65.9 Self-rated health status Very good 301 28.7 Good 440 42.0 Moderate (or fair) 221 21.1 Poor 72 6.9 Very poor 14 1.3 Age Median (Range) 48.0 years (79 years) Length of illness Median (Range) 7 days (0 ) 50.6% females. Of the sample, 24.6% reported an illness; 48.6% dwelled in rural areas; 34.1% had health insur- ance coverage; 65.3% visited health care practitioners (including healers) in the last 4 weeks; 70.7% indicated at least good self-rated health status, and the median age of marriage was 48.0 years (Range = 79 years); while the median length of illness was 7 days (Range = 0 day) (Table 1). Of those who reported an illness, 72.4% indi- cated that the ailment was diagnosed by a medical practi- tioner. The illnesses were colds (6.8%); diarrhoea (0.8%); asthma (3.8%); diabetes mellitus (18.2%); hypertension (34.5%); arthritis (9.1%); and 19.3% indicated an un- specified illness. A significant statistical difference was found between the sexes and age of respondents. The mean age of males was 53.7 years (SD = 15.3 years) compared to 48.0 years (SD = 14.5 years) for females—t statistic = 6.32, P < 0.001. A statistical correlation was found between self- reported illness and sex of respondents—χ2(df = 1) = 8.21, P = 0.003. Twenty-one percent of males reported an ill- ness compared to 28% of females. Concurrently, no sig- nificant statistical correlation existed between self- re- ported diagnosed illness and sex of respondents—χ2(df = 7) = 7.70, P = 0.36. Similarly none was found between medical care-seeking behaviour and sex of respondents —χ2(df = 1) = 0.02, P = 0.50. 64.9% of males visited ahealth care practitioner (including healer) in the last 4 Table 2. Self-reported illness by sex controlled for by area of residence. Sex Area of residence Self-reported illness Male Female Total Yes 19.4 23.1 69 Urban No 80.6 76.9 256 Total 165 160 325 Yes 20.0 20.7 44 Semi-urban No 80.0 79.3 172 Total 105 111 216 Yes 21.9 34.7 146 Rural No 78.1 65.3 367 Total 251 262 513 weeks compared to 65.6% of females. A cross tabulation between self-rated health status and sex revealed no sig- nificant statistical association—χ2(df = 4) = 3.33, P = 0.51. A moderate relationship was found between self-rated health status and age controlled for sex of respondents, correlation coefficient = 0.48; P < 0.05. Furthermore, the mean age of respondents who indicated very good health status was 43.4 years (SD = 11.2 years); 48.8 years (14.1 years) for those who recorded good health status; 59.0 years (SD = 14.7 years) moderate health status; 65.8 years (SD = 13.5 years), poor health status; and 65.8 years (SD = 10.6 years) for those with very poor health status—F statistic [4, 1043] = 75.1, P < 0.001. Concur- rently, a cross-tabulation between self-reported illness and sex of respondents controlled by area of residents revealed that the significant statistical difference was found between rural males and females—χ2(df = 1) = 10.3, P = 0.001: 34.7% of rural females reported an ill- ness compared to 21.9% of rural males (Table 2). A cross-tabulation between self-reported illness and area of residence revealed a significant statistical rela- tionship—χ2(df = 2) = 8.20, P = 0.017: 28.5% of rural respondents reported an illness compared to 21.2% of urban and 20.4% of semi-urban respondents. Similarly a significant statistical association existed between self-reported diagnosed illness and area of resi- dence—χ2(df = 14) = 24.93, P = 0.035. Hypertension was greatest among rural respondents (40.9%) as well as asthma (4.7%); unspecified ailments were greatest among urban residents (28.6%) as well as diabetes mel- litus (21.4%), and colds were greatest among semi-urban respondents (17.8%) (Table 3). A significant statistical correlation existed between self-rated health status and area of residence—χ2(df = 8) = 24.8, P< 0.001. Rural respondents recorded the greatest very poor health status (2.2%) compared to semi-urban (0.0%) and urban dwellers (0.9%). With respect to poor  P. A. Bourne / HEALTH 1 (2009) 332-341 SciRes Copyright © 2009 Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 336 Table 3. Self-reported illness by area of residence. Area of residence Urban Semi-urban Rural Total Characteristic % % % % Self-reported diagnosed illness Cold 2.9 17.8 5.4 6.8 Diarrhoea 0.0 0.0 1.3 0.8 Asthma 2.9 2.2 4.7 3.8 Diabetes mellitus 21.4 15.6 17.4 18.2 Hypertension 21.4 33.3 40.9 34.5 Arthritis 11.4 8.9 8.1 9.1 Unspecified 28.6 15.6 16.1 19.3 Non-diagnosed 11.4 6.7 6.0 7.6 Total 70 45 149 264 Table 4. Self-reported health status by area of residence. Area of residence Urban Semi-urban Rural Total Characteristic % % % % Self-rated health status Very good 31.6 31.3 25.8 28.7 Good 42.1 46.7 39.9 42.0 Moderate 21.7 17.3 22.3 21.1 Poor 3.7 4.7 9.8 6.9 Very poor 0.9 0.0 2.2 1.3 Total 323 214 511 1,048 Table 5. Self-rated health status by social class (in %). Social class Poorest 20% Poor Middle Wealthy Wealthiest20% Total Self-reported health status % % % % % % Very good 20.5 17.7 26.2 34.9 36.3 28.7 Good 42.4 42.5 43.7 39.9 42.0 42.0 Fair 23.2 28.7 22.4 18.1 16.9 21.1 Poor 12.6 8.3 7.7 5.0 4.1 6.9 Very poor 1.3 2.8 0.0 2.1 0.7 1.3 Total 151 181 183 238 295 1048 Table 6. Self-rated health status by self-reported illness. Self-reported illness Yes No Total Characteristic % % % Self-rated health status Very good 4.3 36.8 28.8 Good 24.8 47.5 41.9 Moderate 45.0 13.3 21.1 Poor 21.7 2.0 6.9 Very poor 4.3 0.4 1.3 Total 258 788 1,046  P. A. Bourne / HEALTH 1 (2009) 332-341 SciRes Copyright © 2009 http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/Openly accessible at 337 337 Table 7. Self-rated health status by self-reported diagnosed illness (in %). Self-reported diagnosed illness Cold Diarrhoea Asthma Diabetes Hypertension Arthritis Unspecified No Total Self-rated health status % % % % % % % % % Very good 22.2 0.0 0.0 2.1 3.3 0.0 3.9 10.0 4.6 Good 44.4 0.0 22.2 20.8 17.6 33.3 29.4 40.0 25.5 Moderate 33.3 50.0 33.3 50.0 47.3 41.7 43.1 35.0 44.1 Poor 0.0 0.0 33.3 20.8 27.5 25.0 21.6 10.0 21.7 Very poor 0.0 50.0 11.1 6.3 4.4 0.0 2.0 5.0 4.2 Total 18 2 9 48 91 24 51 20 263 Table 8. Logistic regression: Correlates of good self-rated health status of married people in Jamaica. Explanatory variables OR Std. Error 95% CI R2 Self-reported illness 0.12 0.18 0.01-0.17 0.325 Age 0.94 0.01 0.93-0.96 0.102 Log income 1.32 0.12 1.05-1.66 0.010 Sex (male) 1.63 0.18 1.14-2.32 0.007 Chi square = 383.2 LR = 873.9 health status rural dwellers recorded the greatest per- centage (9.8) and semi-urban (4.7%) and urban respon- dents (3.7%) (Table 4). Conversely, rural respondents recorded the lowest very good health status (25.8%) compared to other residents. A statistical association existed between self-reported health status and social class—χ2(df = 16) = 49.5, P < 0.001. The wealthiest 20% of respondents recorded the highest very good self-reported health status (36.3%) compared to the wealthy (34.9%); middle class (26.2%); poor (17.7%) and the poorest 20% (20.5%) (Table 5). Conversely, the middle class recorded the least very poor health status compared to the other social classes. How- ever, as the social class increased from poorest 20% to wealthiest 20%, the poor health status of the individual declined (Table 5). There is significant correlation between self-reported health status and self-reported illness—χ2(df = 4) = 318.6, P < 0.001. A moderately strong association was found between the two mentioned variables, coefficient corre- lation = 0.48 (Table 6). Based on Table 6, 4.3% of those who indicated having an illness recorded very good health status compared to 36.8% of those who did not indicate an ailment. Of those who indicated having an illness in the last 4 weeks, 26% recorded at least poor health status compared to 2.4% of those who had not indicated an ailment. A statistical correlation existed between self-rated health status and self-reported diagnosed illness—χ2(df = 28) = 47.9, P=0.011. The association between the two variables is a moderate one, correlation coefficient = 0.39. Respondents who indicated chronic illness (i.e. diabetes mellitus, hypertension and arthritis) were more likely to record moderate health status. Of those with chronic illnesses, 231.9% of hypertensive respondents indicated at least poor health status compared to 27.1% of the diabetics, and 25% of the arthritic respondents. Forty-four percent of asthmatic respondents indicated that their health status was at least poor health status (Table 7). Less than 5% of respondents who indicated a chronic illness recorded very good self-reported health status. Furthermore, when self-rated health status and self-reported illness were controlled by sex and age of respondents, the correlation coefficient increased to 0.43, P < 0.001. And when self-rated health status and self-reported illnesses were controlled by sex, age and social class of respondents, the correlation coefficient increased even further to 0.44, P < 0.001. 3.2. Multivariate Analysis The correlates of good health status (including moderate health) of respondents in descending order were self- reported illness (OR = 0.12, 95%CI = 0.01-0.17); age (OR = 0.94, 95%CI = 0.93-0.96); income (OR = 1.32, 95%CI = 1.05-1.66) and sex of respondents (Or = 1.14- 2.32)—χ2(df = 4) = 383.2, P < 0.05. The four variables accounted for 44.4% of the explanatory power of the model, with self-reported illness accounting for 32.5% of the explanatory power. Marital status, education, so- cial class, area of residence and other variables that were identified as significant in relation to self-reported health status using bivariate analysis, dissipated when they were included among other variables in a general collec- tion of variables (Table 9).  P. A. Bourne / HEALTH 1 (2009) 332-341 SciRes Copyright © 2009 Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 338 4. DISCUSSION The current study found that the mean age for married people in Jamaica was 50 years. On disaggregating the data it was revealed that the mean age for married fe- males was 6 years less than that for their male counter- parts (54 years). This finding adds some explanation to the disparity in life expectancy of the sexes in Jamaica, as females are expected to live 6 years longer than males [23,42] and with females who are married 6 years earlier than males; this indicates that the advantage of good health status in married couples does not dissipate the life expectancy gap between the sexes. In wanting to understand why married people have better health status, we found that 51% of married Jamaicans were at least wealthy which more than for the unmarried populace is. Embedded in this finding is the access to financial re- sources which are not available to unmarried Jamaicans, and this accounts for greater health insurance coverage (34%) compared to the populace (21%); less time spent in illness (7 days compared to 10 days for the popula- tion), and they seek more preventative measures, which accounts for the lower time spent receiving medical care. Comparatively 16 out of every 100 Jamaicans reported an illness in 2007 and this was 25 out of every 100 for married people, which indicates two things: 1) their willingness to recognize that they are experiencing ill-health, and 2) the identification of this group’s will- ingness to first accept illness means that they address this more than unmarried people before severity comes into focus, which accounts for the lowered number of days recorded for them in illness. In a study conducted by Hambleton et al. [36], on eld- erly Barbadians, it was found that self-reported current illness accounted for 87.7% of the variability in self-rated health status, and in this research we found it accounted for 73%. Embedded in these findings is the strong importance of illness on self-rated health status. Concurrently, in this paper, we found that a married re- spondent who indicated an illness was 0.12 times less likely to report moderate-to-excellent health status. In addition, the current study found that the mean age of married persons who reported very good self-rated health status was 43 years and the mean age increased as the self-reported health status declined to very poor health: the mean age for those with very poor health status was 66 years and 59 years for those with moderate health. Married people are wealthier, older, with more finan- cial resources at their disposal, and they have 1) more choices; 2) more maturity; 3) more social support; and these cushion the effect of economic hardship which is likely to be experienced by unmarried and single people. Income plays a critical role in determining the health status of people [43] and married people have more of it than unmarried people, which puts them in the advan- tage category of the health status scale. Marmot [43] opined that poverty translated into poor health from the choice of nutrition, milieu and the choice of freedom, and this helps in the explanation of the advantage that income plays in aiding improvements in health status. The current study concurs with Marmot and other stud- ies in that income is correlated with good health status; but disagrees that the correlation is a strong one. The current work showed that income only accounted for 1% of 44.4% explanatory power of good health status of married Jamaicans. Although income opens access to better physical milieu, choice of medical care, education, freedom, general choices and entertainment options, it cannot buy health and it plays a secondary role in im- proving one’s moderate-to-excellent health status. The next variable that is correlated with moderate and beyond health status is age of respondents. The age of respondents accounted for 10.2% of the variability in health status in this study. The current study found a correlation between poor health status and age of re- spondents, and with 50% of the sample being 48 years; 25% being 39 years and 75% being 62 years and below, the better health status is carried across the age cohorts even into older ages for married Jamaicans. Thirty-five percent of the sample recorded having diabetes mellitus compared to 12% of the population; 34.5% had hyper- tension compared to 22.4% of the population and 9.1% had arthritis compared to 8.8% of the population; yet still 71% indicated at least good health and 92% at least moderate health status. This means that preventative care is high among married respondents. It is this preventa- tive mechanism which separates and accounts for some of the health disparity between married and unmarried people. Within the context of the health conditions among married people, preventative lifestyle practice is one of the measures that aid in the health inequality be- tween this cohort and unmarried people, but it also is the choice. A study of 1,147 Jamaicans revealed that there was no significant difference between the health statuses of the sexes [11]. However, in the current study, married males were 1.32 times more likely to report moder- ate-to-excellent health status compared to married fe- males. This begs the question, why life expectancy be- tween the sexes has increased to 6 years since 2004? Since 1988, females have been reporting more illnesses than males, yet still they outlive males on an average by 6 years; it means therefore that marriage increases the current health status of males. The findings of this study revealed that 21 out of every 100 married men reported an illness compared to 28 out of every 100 married women and with the context that the latter group is out- living the former, it can be extrapolated from this study that men are either under-reporting their ill-health or that  P. A. Bourne / HEALTH 1 (2009) 332-341 SciRes Copyright © 2009 Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 339 339 women are more impaired by ill-health than men. A study by Herzog [44] found that elderly women are more impaired by their health problems than men, and that men are more likely to die from them, which goes to the crux of their under-reporting their illness and so they are unable to receive adequate care before severity sets in. Underscoring the under-reporting of ill-health of men, Schoen et al. found [45] that men in general tend to be more stressed and less healthy than females, and further argued that men can use denial, distraction, alcoholism and other social strategies to conceal their illness or dis- abilities. It should be noted here that there was no sig- nificant statistical difference between medical care seeking behaviour of married men (65%) and women (66%), which indicated that men benefit from marriage which is accounted for in their choice to visit health care practitioners (including healers): in 2007, 63% of the male population visited a health care practitioner com- pared to 68% of their female counterparts. Marriage therefore benefits the health status of males. Despite the strong influence of culture on men’s social behaviour, the current study highlights that men’s un- willingness to seek medical care can be reversed. In the general population women outnumber men by 5%; but while married, no statistical difference was found be- tween visits to medical care facilities by the sexes. This suggests that during marriage men will disregard to some degree the culture for the family, as they see their health and longevity as an important family success. Although this study did not examine the psychological status of men and women during marriage, we can ex- trapolate that some aspect of this changes for men, and we see them attending medical care facilities in milieu, which signals weakness and lowered masculinity. Young males are socialized to be strong, masculine and brave, and they are taught to shun the appearance of weakness. One such case is illness. The male child therefore as a part of his socialization is supposed to accept that illness is correlated with weakness, and that he must not be willing to participate in health care seeking behaviour unless it is unavoidable. This definition of unavoidable is embedded into severity, and being unable to rectify the complaint outside of health care practitioners. This gen- der role of the sexes is not limited to Jamaica or the Caribbean, but a study carried out by Ali and de Muynck [46] on street children in Pakistan found a similar gender stereotype. A descriptive cross-sectional study carried out during September and October 2000, of 40 school-aged street children (8-14 years) revealed sever- ity of illnesses, and only when ill-health threatened fi- nancial opportunities, males sought medical care. How- ever, married men will utilize health care facilities more than other men, and this is one of the ways in which they are able to have better health status, as they would be more likely to rectify ailments before severity sets in and premature death results. Recognition of the illness at that time is difficult to cure or averted. Another aspect is the psychological component. It can be deduced from the current findings that marriage pro- vides positive psychological benefits to both parties that are embedded in mortality and suicide data. A study by Kposowa [47] found that divorced and separated people have a greater rate of suicide than married people; and that divorced and separated men are 2.4 times more likely to commit suicide than their female counterparts. One study found that premature mortality from pneumo- nia was 7 times higher for divorced men than married men [48]. Lynch [48] found that divorced or separated men underwent inpatient or outpatient psychiatric care 10 times more often than married men. In Jamaica, the suicide rate disparity between the sexes was 9 times more for men than for women [49]; and while this was not disaggregated by sex from the literature it can be extrapolated that marriage provides psychological bene- fits to men that aid in their better health status, and in- crease the likelihood of their decision to seek medical care, unlike their unmarried counterparts. Like men, marriage provides women with psychological benefits. A study by Stroup & Pollock [50] found that divorced women experienced a 30% decline in income compared to a 10% reduction for their male counterparts. Divorce therefore sees a financial separation from particular life- style choices by the women, which also means that the children as well as the divorced women must now alter their choices owing to this new reality. The financial instability which accompanies divorce denotes that women will be more pressured to carry out some of the roles that previously were left to their husbands. Hence, this role, coupled with the financial challenge of the separation from the man’s resources, demonstrates why divorced women experience more depressive bouts than their married counterparts [51]. For women, the benefits of marriage are more financial, as the literature showed that women, on separation or divorce, experienced greater levels of depression [52-54]. Marriage therefore benefits both sexes. However, like Smith & Waitzman’s [3], and Lillard & Panis [2], this study concurs that the health gains from marriage for men were greater than those for women, and the financial benefits greater for women than men. The financial gains for women from marriage were also documented in a study by Prause et al. [55] which found that married women had higher economic wellbeing than divorced females, and this in- dicates the gains that marriage affords them. 5. CONCLUSIONS Marriage provides greater access to more socioeconomic resources for its participants, as well as increasing men’s  P. A. Bourne / HEALTH 1 (2009) 332-341 SciRes Copyright © 2009 Openly accessible at http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/ 340 unwillingness to visit medical care practitioners. Al- though married people have greater health status, the benefits are different based on the sex of the individual. For men the health gains from marriage are greater than for women; while women benefit more from the finan- cial access to resources. 6. CONFLICT OF INTEREST The author has no conflict of interest to disclose. REFERENCES [1] Moore, E.G., Rosenberg, M.W. and McGuinness, D. (1997) Growing old in Canada: Demographic and geo- graphic perspectives. Nelson, Ontario. [2] Lillard, L.A. and Panis, C.W.A. (1996) Marital status and mortality: The role of health. Demography, 33, 313-327. [3] Smith, K.R. and Waitzman, N.J. (1994) Double jeopardy: Interaction effects of marital and poverty status on risk of mortality. Demography, 31,487-507. [4] Ganster, D.C, Fusilier, M.R. and Mayers, B.T. (1986) The social support and health relationship: Is there a gender difference. J of Occupational Psychology, 59, 145-153. [5] Koo, J., Rie, J. and Park, K. (2004) Age and gender dif- ferences in affect and subjective wellbeing. Geriatrics and Gerontology Int, 4, S268-S270. [6] Ross, C.E., Mirowsky, J. and Goldsteen, K. (1990) The impact of the family on health. J of Marriage and the family, 52, 1059-1078. [7] Gore, W.R. (1973) Sex, marital status and mortality. Am J of Sociology, 30, 189-208. [8] Umberson, D. (1987) Family status and health behaviors: Social control as a dimension of social integration. J of Health and Soci Behavior, 28, 306-319. [9] Goldman, N. (1993) Marriage selection and mortality patterns: Inferences and fallacies. Demography, 30, 189- 208. [10] Bourne, P.A. (2008) Medical sociology: Modeling well-being for elderly people in Jamaica. West Indian Med J, 57, 596-604. [11] Bourne, P.A. (2008) Health determinants: Using secon- dary data to model predictors of well-being of Jamaicans. West Indian Med J, 57, 476-480. [12] Bourne, P.A. and McGrowder, D.A. (2009) Rural health in Jamaica: Examining and refining the predictive factors of good health status of rural residents. Rural and Re- mote Health J, 9, 116, Online. [13] Bourne, P.A. (2009) Socio-demographic determinants of health care-seeking behaviour, self-reported illness and self-evaluated health status in Jamaica. Int J of Collabo- rative Research on Internal Medicine and Public Health, 4, 101-130. [14] Smock, P., Manning, W.D. and Gupta, S. (1999) The effects of marriage and divorce on women’s economic well-being. Am Sociological Review, 64, 794-812. [15] Mastekaasa, A. (1992) Marriage and psychological well- being: Some evidence on selection into marriage. J of Marriage and the Family, 54, 901-911. [16] Diener, E. (1984) Subjective wellbeing. Psychological bulletin, 95, 542-575. [17] Lee, G.R., Seccombe, K. and Sehehan, C.L. (1991) Marital status and personal happiness: An analysis of trends data. J of Marriage and the Family, 53, 839-844. [18] Elwert, F. and Christakis, N.A. (2008) The Effect of widowhood on mortality by the causes of death of both spouses. Am. J. Public Health, 98, 2092-2098. [19] Havens, B. (1995) Long-term care diversity within the care continuum. Canadian J of Aging, 14, 245-262. [20] Koskinen, S., Joutsenniemi, K., Martelin, T. and Marti- kainen, P. (2007). Mortality differences according to liv- ing arrangements. Int J Epidemiol, 36, 1255-1264. [21] Martikainen, P. and Valkonen, T. (1996) Mortality after death of spouse in relation to duration of bereavement in Finland. J of Epidemiol and Community Health, 50, 264-268. [22] Bourne, P .A. (2009) Dichotomising poor self-reported health status: Using secondary cross-sectional survey data for Jamaica. North American J of Med Sci, 1(6), 295-302. [23] World Health Organization (WHO) (2009) World health statistics, 2009. WHO, Geneva. [24] Christakis, N.A. and Allison, P.A. (2006) Mortality after hospitalization of a spouse. The New England J of Medi- cine, 354, 719-730. [25] Stutzer, A. and Frey, B.S. (2006) Does marriage make people happy or do happy people get married. J of So- cial-Economic, 34, 326-347. [26] Ben-Shlomo, Y., Smith, G.D., Shipley, M. and Marmot, M.G. (1993) Magnitude and cause of mortality differ- ences between married and unmarried men. J of Epide- mio and Community Health, 47, 200-205. [27] Cheung, Y.B. (2000) Marital status and mortality in Brit- ish women a longitudinal study. Int J Epidemiol, 29, 93-99. [28] Cohen, L. and Holliday, M. (1982) Statistics for Social Sciences. Harper & Row, London. [29] Hair, J.F., Black, B., Babin, B.J., Anderson, R.E. and Tatham, R.L. (2005) Multivariate data analysis, 6th edi- tion. Prentice Hall, New Jersey. [30] Mamingi, N. (2005) Theoretical and empirical exercises in econometrics. University of the West Indies Press, Kingston. [31] Zar, J.H. (1999) Biostatistical analysis, 4th edition. Pren- tice Hall, New Jersey. [32] Hamilton, J.D. (1994) Time series analysis. Princeton University Press, New Jersey. [33] Kleinbaum, D.G., Kupper, L.L. and Muller, K.E. (1998) Applied regression analysis and other multivariable methods. PWS-Kent Publishing, Boston. [34] Cohen, J. and Cohen, P. (1983) Applied regres- sion/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences, 2nd edition. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, New Jersey. [35] Koutsoyiannis, A. (1977) Theory of econometrics, 2nd ed. MacMillan Publishing, New York. [36] Hambleton, I.R., Clarke, K., Broome, H.L., Fraser, H.S., Brathwaite, F. and Hennis, A.J. (2005) Historical and current correlates of self-reported health status among elderly persons in Barbados. Revista Panamericana de Salud Pứblica, 17(5-6), 342-352.  P. A. Bourne / HEALTH 1 (2009) 332-341 SciRes Copyright © 2009 http://www.scirp.org/journal/HEALTH/Openly accessible at 341 341 [37] Grossman, M. (1972) The demand for health—a theo- retical and empirical investigation. National Bureau of Economic Research, New York. [38] Smith, J.P. and Kington, R. (1997) Demographic and economic correlates of health in old age. Demography, 34, 159-70. [39] Idler, E.L. and Benjamin, Y. (1997) Self-rated health and mortality: A review of twenty-seven community studies. J of Health and Social Behavior, 38, 21-37. [40] Idler, E.L. and Kasl, S. (1995) Self-ratings of health: Do they also predict change in functional ability? J of Ger- ontology, 50B(6), S344-S353. [41] Finnas, F., Nyqvist, F. and Saarela, J. (2008) Some meth- odological remarks on self-rated health. The Open Public Health J, 1, 32-39. [42] Statistical Institute of Jamaica (STATIN) (2006) Demo- graphic statistics, 2005. STATIN, Kingston. [43] Marmot, M. (2002) The influence of income on health: Views of an Epidemiologist. Does money really matter, or is it a marker for something else? Health Affairs, 21, 31-46. [44] Herzog, A.R. (1989) Physical and mental health in older women: Selected research issues and data sources. In: Hendricks J.A., editor: Health and economic status of older women: Research issues and data sources. Bay- wood Publishing, New York. [45] Schoen, C., Davis, K., DesRoches, C. and Shekhdar, A. (1998) The health of adolescent boys: Commonwealth Fund survey findings. Commonwealth Fund, New York, [46] Taff, N. and Chepngeno, G. (2005). Determinants of health care seeking for children illnesses in Nairobi slums. Tropical Medicine and Int Health, 10, 240-45. [47] Kposowa, A.J. (2003) Divorced and suicide risk. J Epidemiol Community Health, 57, 993. [48] Lynch, J.J. (1977) The broken heart: The medical consequences of loneliness. Basic Books, New York,. [49] Abel, W.D., Bourne, P.A., Hamil, H.K., Thompson, E.M., Martin, J.S., Gibson, R.C. and Hickling, F.W. (2009). A public health and suicide risk in Jamaica from 2002 to 2006. North American J of Med Sci, 1(3), 142-147. [50] Stroup, A. and Pollock, G. (1994) Economic consequences of martial dissolution. J of Divorce and Remarriage, 22, 37-54. [51] Lorenz, F.O., Simons, R.L., Conger, R.D., Elder, G.H.Jr., Johnson, C. and Chao, W. (1997) Married and recently divorced mothers’ stressful events and distress: Tracing change across time. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 59, 219-232. [52] Cano, A. and O’Leary, K.D. (2000) Infidelity and separations precipitate major depressive episodes and symptoms of nonspecific depression and anxiety. J of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68, 774-781. [53] Christian-Herman, J.L., O’Leary, K.D. and Avery-Leaf, S. (2001) The impact of severe negative events in marriage on depression. J of Soci and Clinical Psychology, 20, 25-44. [54] Kendler, K.S., Thornton, L.M. and Gardner, C.O. (2000) Stressful life events and previous episodes in the etiology of major depression in women: An evaluation of the “kindling” hypothesis. Am J of Psychiatry, 157, 1243-1251. [55] Prause, W., Saletu, B., Tribl, G.G., Rieder, A., Rosenger- ger, A., Bolitschek, J., Holzinger, B., Kaplhammer, G., Datschning, H., Kunze, M., Popovic, R., Graetzhofer, E. and Zeitlhofer J. (2005) Effects of socio-demographic variables on health-related quality of life determined by the quality of life index—German version. Human psy- chopharmacology Clinical and Experimental, 20, 359-365. |