iBusiness

Vol.2 No.3(2010), Article ID:2704,8 pages DOI:10.4236/ib.2010.23035

Power Perspective: A New Framework for Top Management Team Theory

![]()

School of Management, University of Shanghai for Science and Technology, Shanghai, China.

Email: {cym23, gyh3830}@163.com, andyszq@sina.com

Received April 30th, 2010; revised June 6th, 2010; accepted July 12th, 2010.

Keywords: Top Management Team, Power, Framework

ABSTRACT

Top management team theory (TMTT) has been researching on the relationship between top management team (TMT) and organization outcome through demographic characteristic and its heterogeneity. As the researcher failed to solve the “black box” problem, they get no consistent findings. Power perspective of TMTT will help out of the research predicament, so to focus on combing and assessing the TMT power, demographic characteristic based TMTT research and TMT team process. Based on the early research works, new research framework of power-based TMTT and future research suggestions are proposed.

1. Introduction

The emerging field of strategic decision-making - top management team theory (hereinafter refers to as TMTT) from Hambrick [1] has raised widespread concern in the academic community [2-5] . Different from traditional strategic management theory, which emphasizes on purely economic and technological processes or information process, TMTT studies the strategic choice and organizational performance determinants from the process of cognitive psychology of top management team (TMT), which overturns the economic man hypothesis in traditional theory and proposes the hypothesis of limited rationality proposed by the Carnegie school [6-7] . As the cognitive psychological process of TMT is too complicated, TMTT invokes prior marketing research on demography to suggest that managerial characteristics and its heterogeneity (such as age, work experience, educational background, etc.) are reasonable proxies for underlying differences in cognitions, values, and perceptions process, which could be good predictor to predict organizational outcome (such as strategic choice, organizational performance, etc.) [8-11] .

Although three major theoretical advantage gained according to the using of demographic methods: more easy to predict organizational outcome than other strategic management theory, more easy to select and train executives, more convenient and relatively effective to predict the competitor’s strategic behavior [1] , a lot of empirical research findings find that the finding of the relationship between heterogeneity of demographic characteristics and output projections of the organization is not consistent [12] or even no findings [13] . In other words, the same level of demographic characteristics and its heterogeneity do not necessarily reflect the organizational outcome of the same level. As the appearance of inconsistency, the theoretical advantage of TMTT has no longer existed. So, to solve inconsistencies problem has become the most pressing issue of TMTT study.

As a result, some researchers begin doubting the feasibility of using demographic characteristic method [13-15] , for which the demographic characteristics’ coarse nature [7] which cannot effectively proxy the process of cognitive psychology process. There exist tremendous barriers and a lot of questions such as how, why, and when TMT demographics map on to particular cognitions, socio - cognitions, and behaviors [7] . Some researchers propose to abandon the demographic characteristics and focus on the process of cognitive psychology of TMT [6,8] . Nevertheless, it is just like stop eating for fear of choking. If we analyze directly from the process of cognitive psychology of TMT, it would not only difficult to collect the relevant research data, but also difficult to obtain the theoretical advantage gained by using the demographic characteristics [16] . Thus, the prediction inconsistencies can not solve without the relevant variables of demographic characteristics. In fact, the reason of prediction inconsistencies problem is attributed to two main reasons: on the one hand, demographic characteristics subject to the external environment; on the other hand, it subjects to the interaction within the team. The prediction inconsistencies problem can be solved through adding these two factors to the original demographic characteristics and its heterogeneity studies. With regard to the external environmental factors, researchers have incorporated environment variable into the research which has been studied a lot [17,18] ; While interacting factors on the team is more complex and has not been effectively addressed, which is known as the TMTT’s “black box” problem [12] .

In recent years, in order to solve this “black box” problem, new research trend emerges in TMTT - “the team process trend”. The so - called “team process trend” refers to TMTT research gradually moved from the perspective of demographic characteristics to the perspective of combination of demographic characteristics and team process which is a research trend which constantly moving forward to the very cognitive psychology process of TMT decision-making [7,19,20] “Team process” which also known as group process, means the behavioral types emerging from the accomplishment process of specific tasks, such as conflict, cooperation [21] , communication [22] and so on. However, the existing TMTT research often concerns about the moderating role of conflict, cooperation or communication level in the relation between the demographic characteristics and the organizational outcome, which pays far from enough attention to the latent variable behind conflict and other process - the core of decision-making process variable - power [23] .

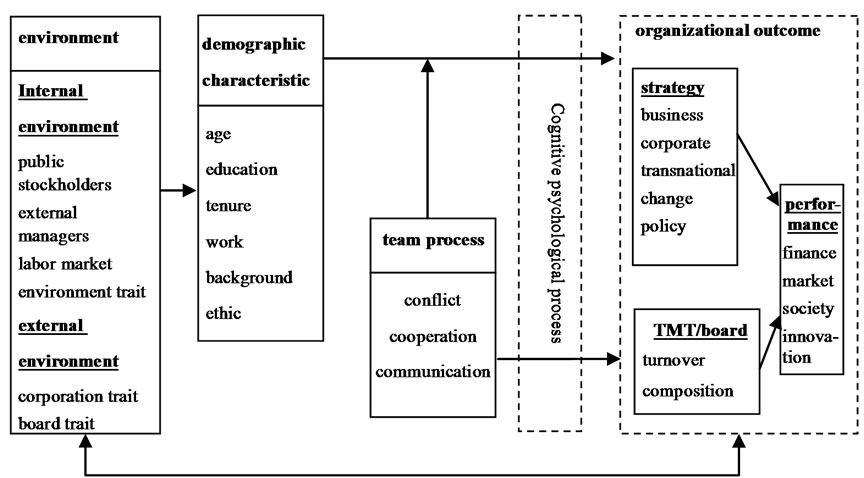

In order to illustrate the TMTT more visually, we put it in a diagram depicted in Figure 1.

Power is the core of strategic decision-making in organization [24] . Many scholars take the power factors into strategic decision-making research [25-27] . However, in TMTT, despite some scholars have been calling on repeatedly [23] , the power perspective of TMTT study is still few and far between. This phe nomenon may occur partly due to the power may be more difficult to define and measure compared to the demographic characteristics variables; on the other hand, the interactionmechanism between TMT power and demographic characteristics and team process. In fact, it is easy to observe that there is shadow of power behind varieties of the team process variable. Generation, distribution and evolution mechanism of power will affect team process to certain degree. Therefore, research on the relationship between demographic characteristics and team processes and organizational outcome in the power perspective should be emphasized in TMTT research. In the efforts of solving the “black box” problem, if TMTT study ignores the power factors role in the team process, it would be difficult to break through the current bottleneck.

This article will review the relevant literature of power in the upper echelons domain through the source of power, the interaction among power, demographic characteristics and team process, etc., point out the importance of power perspective in TMTT research, and propose an initial general research framework.

Figure 1. Traditional research framework of TMTT.

2. The Relationship between Demography and the Source of Power

Hambrick [28] , the proposer of TMTT, has preliminarily researched in the powers of TMT before proposing the TMTT. He suggested that the external environment and organizational strategies will bring a range of uncertainty and associate with which there is a series of contingencies; TMT is the team to cope with these occasional events - the salient features of the distinction between TMT and other teams - the ability to cope with these contingencies directly determines the level of executive’s power. He uses jobs and information searching behavior to replace the ability to respond to contingencies, and found that the most powerful positions are those positions which most suitable with the organizational environment and organizational strategies. For instance, under the condition of rapid changing market or products, those executives who closely related to the production outcome will gain more power; the same is true on the organizational strategy. That is to say, those executives who closely related to the production outcome will gain more power in the aggressive strategy than in defensive strategy. Although this research method is sketchier, but the importance of this study is that it gives the TMT an understanding of sources of power: the power of TMT comes from the capacity to cope with uncertainty which caused by environmental and strategic changes - this is the beginning of the study of TMT power.

The first thing we have to make it clear is the meaning of power if to analyze the source of TMT power. From the perspective of organizational resources, power refers to is the ability to access and use of resources [29] , but this definition ignores the interactive relationship between people, and more and more scholars define power as the ability of individual to act according to their wishes (Finkelstein, 1992). It is clear from these two definitions that power comes from ability, which makes the power subject superior than the power receptors. As far as top management power is concern, this superiority is reflected the discourse right edge, and information and resource advantages in the decision-making process. More deeply, such superiority on the one hand comes from the organization’s residual control rights (i.e., shareholder power) and derivative of residual control (such as the manager’s power), which brings in overt power; On the one hand from the decision-making capacity, which brings in the covert power. Before Hambrick (1981), a lot of literature that researched in the source of power focuses on the objects of single decision-makers such as CEO, chairman etc., or of any employees in organization [28] , while pays not good enough attention to power of decision-making team, especially TMT. Finkelstein (1992) is one of the few scholars who researched into the TMT power [30] . He proposes the four-dimensional model of power from the perspective of sources of power, and his methodology for measuring executive power is comprehensive and well-validated. In the model, power has four dimensions: structured power, ownership of power, reputation power and expert power. The so-called structural power refers to individual power gains through difference in organizational structure status; ownership power is the power gains through different percentage in shares; reputation power is the power gains through different reputation inside and outside the organization; and expert power is the power gains through different expertise knowledge. We can see that the first two are the overt power mentioned above, while the latter two are the covert power. To what degree will power affect decision-making and whether there are differences between them, and whether there is interaction between two kinds of power, all of which need further research.

Looking further into sources of power, we can find that there is an important feature of power: the dynamic feature. Power owners on the one hand use of existing powers to obtain greater power and interests, and on the other hand subject to the constraints from all sides. Pollock et al. (2002) find that the powerful CEO has greater ability to change the strike price of its stock options [31] . Shen & Jr Cannella (2002) point out that market and shareholders would evaluate firm and CEO through firm performance [32] . When firm performance declines, personal honor and value of CEO would decline respectively and his power status thus would be threatened; when the CEO isn’t competent for the job, the other executives will be in conjunction with other members to challenge CEO’s status, aiming at seizing the power. Thus, CEO positions will be coveted by other executives at all times, and the struggle of power between executives will be correlate with CEO’s departure and the new arrival of his successor Therefore, from the perspective of dynamic feature of power, power derives from the struggle and can never exist without struggle.

In addition, the power is also derived from the individual’s perception. Power is perceived by receptors of power which is relative, and is the power recognized by the power receptor [33] , so the strength of power is related to individual metal perception. This discovery has an important impact on the research of TMT power: on the one hand it is necessary to strengthen the research of psychological mechanism of TMT power, on the other hand, the power also need to be measured effectively. At present, the majority of the research use of psychological scales to measure the perception of mutual power; Eisenhardt and Bourgeois (1988) developed a psychological scale which is more integrate and useful and used by most power researcher directly or indirectly to measure power [33] . Finkelstein (1992) develops new measurement of power base on the work of Eisenhardt and Bourgeois [30] , but these methods have the problem of low accuracy. So, how to measure the perceived power of the TMT more accurately will urge us to do further research in-depth.

The research on source of power of TMT above is basically independent of the TMTT’s research, in particular the research of TMT demographic characteristics and its heterogeneity. In fact, the source of power of TMT and TMT demographic characteristics are inexorably linked. In Finkelstein (1992)’s four-dimensional model of power [30] , the two overt powers, namely, structural power and ownership power, can be available from jobs, property status and other demographic characteristics information; and covert power, that reputation power and expert power, can also be reflected by some demographic characteristics. For instance, TMT’s educational background, firm tenure, industry experience and other demographic characteristics, can be used as proxies for the variables of reputation power which highly associate with social capital. And education, age and other demographic characteristics can act as expert power proxies which highly associate with human capital. On this basis, we can roughly understand the power distribution of TMT. If some team members’ human capital or social capital significantly higher than the other team members (observed through demographic heterogeneity) in certain organization, we can conclude that it is a relatively centralized organization. This method of demographic heterogeneity is different from method of demographic heterogeneity used in TMTT in the past., which the latter one is a general difference, while the former is a specific difference, which used for executives to determine power distribution of the team. This will incorporated power distribution in the TMTT demographic characteristics analysis, which will help solve the TMTT’s “black box” problem. However, this idea needs to further empirical research comparing the psychological perception based power distribution and demographic characteristics based power distribution to verify the feasibility of the latter. At the same time, it need to be in-depth study that whether the dynamic evolution of power can be proxies the demographic characteristics.

3. The Mediating Role of Power in TMTT Research

Since the TMTT has been proposed, related research mainly focused on demographic characteristics perspective until Finkelstein (1992) who only then takes power into the TMT to TMTT research framework [30] . He notes that when TMTT choosing the research object, it is the same with the research of TMT power which is two sides of the same coin [30] . In other words, if the distribution of executives’ power is highly concentrated, then the CEO can be chosen to replace the TMT to conduct research; On the contrary, if the distribution of executives’ power is not highly concentrated, then the choice of studying the TMT can be significant, because the distribution of power determines the subject affected strategic options. Meanwhile, Finkelstein (1992) points out that the proportion of members with a financial background in TMT will have a significant positive correlation with the number of mergers and acquisitions transactions, which are the general conclusions under demographic methods. However, if power distribution of team members’ financial background is included, the predictive power of the conclusion would be much stronger. This shows that not only the proportion functional background or other demographic characteristics impact strategic choice related to the function, powers of the functions will also affect the strategic choice, so the forecast of decision-making is inseparable from the analysis TMT powers. However, Finkelstein (1992) analyzes only a certain type of demographic characteristics. Later, Pitcher and Smith (2001) are working on meditation role of power and other mediators in the relation of all relevant demographic characteristics and organizational outcome [34] . They find that TMT power significantly meditate the relationship of certain demographic characteristics and organizational outcome while in other relationship the mediating role of TMT is not obvious enough through three typical cases of analysis. When we predict organizational innovation, the heterogeneity of industry experience and personality are not affected by the power significantly while in the heterogeneity of functional area, power affected significantly. However, such conclusions based on the analysis of typical cases seem to be rather weak. To get more convincing evidence need in-depth study. In addition, Pitcher and Smith (2001) focus on the moderating role of TMT power [34] . They use of team members power index as weight to justify demographic characteristics, and examine the relationship between justified characteristics and organizational outcome, but have neglected the direct correlation and impact of TMT power on organizational outcome.

Smith et al. (2006) research in-depth the relationship between TMT power distribution and organizational performance and analyze the role of demographic characteristics [23] . They mainly study three questions: First, what is the form of distribution of TMT power (even or uneven)? Second, whether the distribution of TMT power with corporate performance? Third, if the distribution of TMT power correlated with corporate performance, then, were there significant demographic characteristics differences between high performers and low performers? The result shows that there is a positive relationship between uneven power distribution TMT and corporate performance, and also generates the TMT power duo phenomenon, that is, when the majority of power concentrates in two people, and the two’s demographics characteristics (mainly age and industry experience) have great heterogeneity, the performance will be higher [23] . The study is very important which also further deepen the TMTT. Traditional corporate governance theory tend to only attach importance to the role of CEO that the CEO is the key to deal with the relationship between enterprises and the outside world; and TMTT’s past research find that TMT is the entities to deal with the relationship between enterprises and the outside world. However, Smith et al. (2006) find out a new organizational model of decision-making - the power duo, clearly point out that to make good organizational performance, it is necessary to concentrate power on two people - CEO and the second powerful people - whose demographic characteristics need great heterogeneity [23] . However, the analysis is based on short-term and single - industry study, of which conclusion’s scope of application needs further verification.

It can be seen from above that on one hand power acts as a moderator in the relationship between TMT demographic characteristics and its heterogeneity and organizational outcome, on the other hand directly impact on organizational outcome, while the demographic characteristics and its heterogeneity moderate this relationship in turn. But whether it is the truth requires more stringent proof. Meanwhile, as interpret in the above section, the TMT power can be describe by demographic characteristics and even more, can be incorporated into the TMTT research framework. Research in this area is relatively rare which is worth noting.

Considering the team process, there are not many Literatures combining demographic characteristics, power and team process to TMTT, Umans (2008) is the most representative one amongst the else [35] . He studied the relationship between culture heterogeneity of demographic characteristics and power distribution, in addition to find that cultural heterogeneity positively related to team communication process, also find that demographic heterogeneity correlate with power distribution. However, this study is limited to one kind of heterogeneity in demographic characteristics and one kind of team process, and uses case analysis, although this will help indepth analysis of the team process, rigorousness and universality of the conclusions can not be guaranteed. In addition, the study that demographic characteristics impact on power distribution is limited to respondents’ subjective feeling, without time-series analysis, so the conclusion is not stable. Finally, the inadequacy of the study lies in no inspection is taken on the relationship between power and team process, and therefore can not determine whether the demographic characteristics first act on power and then on team process, or there are other mechanism.

In the TMTT, on the relationship chain demographic characteristics affect organizational outcome, the team process and other more complex cognitive processes which are generally considered as an unknown “black box”. However, after Umans (2008)’s research, it can be explored and to know. TMT power is the key entry point to solve the “black box” problem. Demographic characteristics may firstly act on the TMT power, and then the heterogeneity of power determines different team interaction process, and different team process will inevitably lead to different cognitive processes, and thus affects the outcome. The clearness of this research chain is conducive to solve the “black box” problem, as well as the development of TMTT.

4. New Research Framework of Power-Based TMTT and Research Prospects

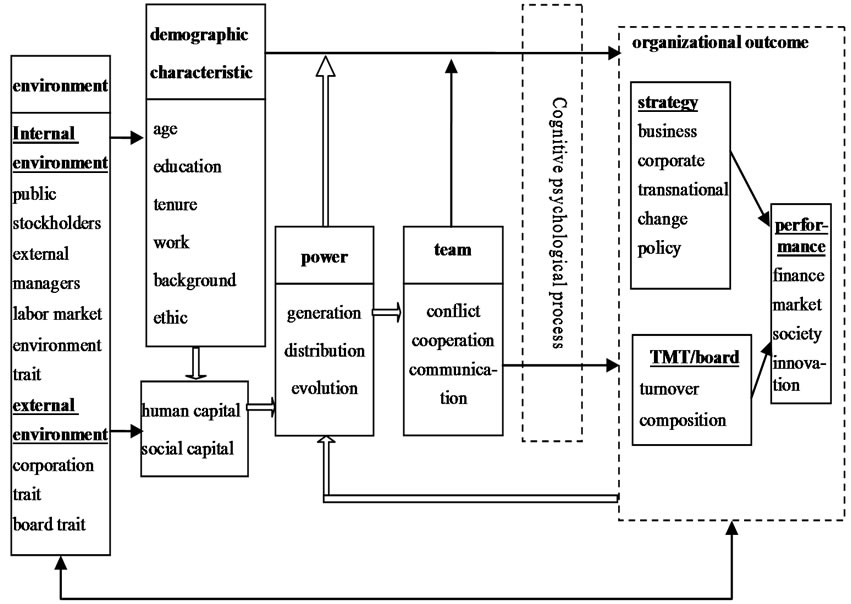

Taking the review above into account, combined with the research suggestion from Carpenter et al. [7] , this paper propose a new research framework of power-based TMTT which shows in Figure 2.

In Figure 2, the single solid line arrows refers to the relatively mature research path in the theoretical framework of TMTT, double-line arrow is the path need to be further explored; the cognitive psychological process in the dashed box is part of the “black box” problem that is not effectively open in TMTT as it was very complex which will not discuss in-depth in the framework we proposed in this paper. It can be seen from Figure 2, the TMTT research paths that need to be strengthened is basically emanate from TMT power.

First of all, from the source of power perspective, we holds that the power of TMT comes mainly from the capital owned by its executives, including human capital and social capital. In fact, large number of previous TMT power sources research can basically take into the research areas of human capital and social capital, but few scholars have research the TMT power source from these two capital perspective. At the same time, combining current TMTT demographic characteristics research, a latent path of demographic characteristics acting on the TMT power is to proxy the human capital and social capital, and then took part in the process of TMT power, team processes acting on organizational outcome.

Figure 2. New research framework of power-based TMTT.

Through the introduction of power perspective, the inconsistency problems of TMTT in the demographic characteristics and its heterogeneity research can be resolved, while the research can still take the advantage of demographic characteristics method.

Secondly, as far as the research of TMT power per se is concerned, it need to change form static research to dynamic research; that is to investigate TMT power from static perspective and then look into the evolutionary mechanism and the combined effect of the three in-depth. This approach is quite rare in TMTT current research.

Thirdly, the moderating role in TMT power and organizational outcome need further research. These further researches include the moderating roles of TMT generation, distribution and evolution mechanisms, and the research based on different industries, different organizations, and different size of the organization.

Fourth, research in the relationship between TMT power and team process is not enough. However, in TMTT framework, to research in the relationship between TMT power and team process combining variables such as demographic characteristics will have great theoretical significance in solving the “black box” problem of TMTT.

Fifth, strengthen the research on the impact of organizational outcome on TMT power, which is very important step to enrich and develop TMTT theory. In fact, TMTT should be a closed system based theory, but in almost all previous studies neglected this point. As can be seen from Figure 1, if to say the traditional TMTT research is a positive feedback process, and then we tend to overlook the negative feedback process from organizational outcome to TMT power, these two processes combine to form a closed system. And this feedback loop is the premise of TMTT dynamic study which is the base to explore TMTT evolution mechanism under the time dimension. Thus, in the framework of TMTT, to research the impact of organizational strategy, TMT or board situation and organizational performance on TMT power has great theoretical and practical significance.

REFERENCES

- D. C. Hambrick and P. A. Mason, “Upper Echelons: The Organization as a Reflection of its Top Managers,” The Academy of Management Review, Vol. 9, No. 2, 1984, pp. 193-206.

- P. Greve, S. Nielsen and W. Ruigrok, “Transcending Borders with International Top Management Teams: A Study of European Financial Multinational Corporations,” European Management Journal, Vol. 27, No. 3, 2009, pp. 213-224.

- S. Nielsen, “Why do Top Management Teams Look the Way They Do? A Multilevel Exploration of the Antecedents of TMT Heterogeneity,” Strategic Organization, Vol. 7, No. 3, 2009, pp. 277-305.

- C. Boone and W. Hendriks, “Top Management Team Diversity and Firm Performance: Moderators of Functional-Background and Locus-of-Control Diversity,” Management Science, Vol. 55, No. 2, 2009, pp. 165-180.

- A. Carmeli and M. Y. Halevi, “How Top Management Team Behavioral Integration and Behavioral Complexity Enable Organizational Ambidexterity: The Moderating Role of Contextual Ambidexterity,” The Leadership Quarterly, Vol. 20, No. 2, 2009, pp. 207-218.

- D. C. Hambrick, “Upper Echelons Theory: An Update,” Academy of Management Review, Vol. 32, No. 2, 2007, pp. 334-343.

- M. A. Carpenter, M. A. Geletkanycz and W. G. Sanders, “Upper Echelons Research Revisited: Antecedents, Elements, and Consequences of Top Management Team Composition,” Journal of Management, Vol. 30, No. 6, 2004, pp. 749-778.

- R. L. Priem, D. W. Lyon and G. G. Dess, “Inherent Limitations of Demographic Proxies in Top Management Team Heterogeneity Research,” Journal of Management, Vol. 25, No. 6, 1999, pp. 935-953.

- M. A. Carpenter, “The Implications of Strategy and Social Context for the Relationship between Top Management Team Heterogeneity and Firm Performance,” Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 23, No. 3, 2002, pp. 275-284.

- B. J. Olson, S. Parayitam and N. W. Twigg, “Mediating Role of Strategic Choice between Top Management Team Diversity and Firm Performance: Upper Echelons Theory Revisited,” Journal of Business & Management, Vol. 12, No. 2, 2006, pp. 111-126.

- D. Naranjo-Gil, F. Hartmann and V. S. Maas, “Top Management Team Heterogeneity, Strategic Change and Operational Performance,” British Journal of Management, Vol. 19, No. 3, 2008, pp. 222-234.

- B. S. Lawrence, “The Black Box of Organizational Demography,” Organization Science, Vol. 8, No. 1, 1997, pp. 1-22.

- C. T. West Jr. and C. R. Schwenk, “Top Management Team Strategic Consensus, Demographic Homogeneity and Firm Performance: A Report of Resounding Nonfindings,” Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 17, No. 7, 1996, pp. 571-576.

- M. D. Ensley, A. Pearson and C. L. Pearce, “Top Management Team Process, Shared Leadership, and New Venture Performance: A Theoretical Model and Research Agenda,” Human Resource Management Review, Vol. 13, No. 2, 2003, pp. 329-346.

- M. D. Ensley and K. M. Hmieleski, “A Comparative Study of New Venture Top Management Team Composition, Dynamics and Performance between UniversityBased and Independent Start-Ups,” Research Policy, Vol. 34, No. 7, 2005, pp. 1091-1105.

- J. Li and D. C. Hambrick, “Factional Groups: A New Vantage on Demographic Faultlines, Conflict, and Disintegration in Work Teams,” Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 48, No. 5, 2005, pp. 794-813.

- J. Haleblian and S. Finkelstein, “Top Management Team Size, CEO Dominance, and Firm Performance: The Moderating Roles of Environmental Turbulence and Discretion,” The Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 36, No. 4, 1993, pp. 844-863.

- E. H. Offstein, G. Harrell-Cook and A. Tootoonchi, “Top Management Team Discretion and Impact: Drivers of a Firm’s Competitiveness,” Competitiveness Review, Vol. 15, No. 2, 2005, pp. 82-91.

- R. S. Peterson, D. B. Smith, P. V. Martorana and P. D. Owens, “The Impact of Chief Executive Officer Personality on Top Management Team Dynamics: One Mechanism by Which Leadership Affects Organizational Performance,” Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 88, No. 8, 2003, pp. 795-808.

- T. Hutzschenreuter and I. Kleindienst, “Strategy-Process Research: What Have We Learned and What is Still to Be Explored,” Journal of Management, Vol. 32, No. 5, 2006, pp. 673-720.

- L. H. Pelled, K. M. Eisenhardt and K. R. Xin, “Exploring the Black Box: An Analysis of Work Group Diversity, Conflict, and Performance,” Administrative Science Quarterly, Vol. 44, No. 1, 1999, pp. 1-28.

- K. G. Smith, K. A. Smith, J. D. Olian, H. P. Sims, D. P. O’Bannon and J. A. Scully, “Top Management Team Demography and Process: The Role of Social Integration and Communication,” Administrative Science Quarterly, Vol. 39, No. 3, 1994, pp. 412-438.

- A. Smith, S. M. Houghton, J. N. Hood and J. A. Ryman, “Power Relationships among Top Managers: Does Top Management Team Power Distribution Matter for Organizational Performance?” Journal of Business Research, Vol. 59, No. 5, 2006, pp. 622-629.

- J. Child, “Organizational Structure, Environment, and Performance: The Role of Strategic Choice,” Sociology, Vol. 6, No. 1, 1972, pp. 1-22.

- P. Fleming and A. Spicer, “Beyond Power and Resistance: New Approaches to Organizational Politics,” Management Communication Quarterly, Vol. 21, No. 3, 2008, pp. 301-309.

- J. Pfeffer and C. T. Fong, “Building Organization Theory from First Principles: The Self-Enhancement Motive and Understanding Power and Influence,” Organization Science, Vol. 16, No. 4, 2005, pp. 372-388.

- H. Mitsuhashi and H. R. Greve, “Powerful and Free: Intraorganizational Power and the Dynamics of Corporate Strategy,” Strategic Organization, Vol. 2, No. 2, 2004, pp. 107-132.

- D. C. Hambrick, “Environment, Strategy, and Power within Top Management Teams,” Administrative Science Quarterly, Vol. 26, No. 2, 1981, pp. 253-275.

- R. G. Rajan and L. Zingales, “Power in a Theory of the Firm,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 113, No. 2, 1998, pp. 387-432.

- S. Finkelstein, “Power in Top Management Teams: Dimensions, Measurement, and Validation,” The Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 35, No. 3, 1992, pp. 505- 538.

- T. G. Pollock, H. M. Fischer and J. B. Wade, “The Role of Power and Politics in the Repricing of Executive Options,” The Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 45, No. 6, 2002, pp. 1172-1182.

- W. Shen and A. A. Cannella Jr., “Power Dynamics within Top Management and their Impacts on CEO Dismissal Followed by Inside Succession,” The Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 45, No. 6, 2002, pp. 1195-1206.

- K. M. Eisenhardt and L. J. B. III, “Politics of Strategic Decision Making in High-Velocity Environments: Toward a Midrange Theory,” The Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 31, No. 4, 1988, pp. 737-770.

- P. Pitcher and A. D. Smith, “Top Management Team Heterogeneity: Personality, Power, and Proxies,” Organization Science, Vol. 12, No. 1, 2001, pp. 1-18.

- T. Umans, “Ethnic Identity, Power, and Communication in Top Management Teams,” Baltic Journal of Management, Vol. 3, No. 2, 2008, pp. 159-173.

NOTES

*This paper is sponsored by The Innovation Fund Project For Graduate Student of Shanghai(JWCXSL1001) and The Key Innovation Program of Shanghai Municipal Education Commission(10ZS96) and Key Subject of Shanghai Municipal(3rd period)(S30504).