Health

Vol.5 No.1(2013), Article ID:26526,10 pages DOI:10.4236/health.2013.51011

Announcers and confessors: How people self-disclose depression in health panels

![]()

Research & Innovation, North Bristol NHS Trust, Bristol, UK; nicolawilliams6@nhs.net

Received 4 October 2012; revised 8 November 2012; accepted 16 November 2012

Keywords: Health; Disclosure; Qualitative; Group Interaction; Sensitive Topics

ABSTRACT

Focus groups can be used to explore sensitive topics and have been found to increase the likelihood and depth of disclosure of personal and sensitive information in comparison to individual interviews. This article focuses on how people make self-disclosures in group research settings, specifically self-disclosure of depression. Data was collected from twelve health panel groups, held in Somerset, England. Health panels are a focus group-based method where members of the public are brought together to discuss a variety of topics including sensitive ones. The topic discussed by the health panel was attitudes to help-seeking for stress and depression. In this paper I conceptualize two new types of discloser—which I term “announcers” and “confessors” and illustrate how normalizing language can facilitate disclosures. This study has important implications for focus groupbased research and for health professionals who deal with stigmatized conditions such as depression.

1. INTRODUCTION

Focus groups are frequently used as a method to access views on health [1] and a primary goal of focus groups is to encourage self-disclosure [2]. Most research focuses on “what” participants thought rather than “why” and “how” they thought [3]. This article focuses on how people make self-disclosures in group research settings, specifically self-disclosure of depression, and identifies two new conceptual styles of self-disclosure.

Focus groups differ from other qualitative methods in that interaction occurs between participants, and between the moderator and participants [4]. The interactions within focus groups can be summarized as concerned with: confirming knowledge or expertise; requesting information or support; validating and challenging others; and facilitating disclosures [5]. Disclosures can be defined as “personal revelations of thoughts or actions that were often painful to the speaker and that risked censure because they were contrary either to family or social mores or to their role expectations” [6]. Although some texts recommend that focus groups should be avoided for sensitive topics [7] most research suggests the reverse— focus groups can facilitate the disclosure of personal and sensitive information rather than impede it in comparison to individual interviews. Few make reference to how this facilitation occurs, although some suggest focus groups enable participants to negotiate the individual status context and power dynamics more easily—participants are able to disagree with each other and with the moderator because power is devolved from the moderator to the group and participants support each other in challenging each others’ views [8].

A key factor in encouraging disclosure is that focus group participants are able to establish common ground which increases their courage to share information when they discover others feel or have experienced the same [3,9]. For example, research with sex-workers has demonstrated that disclosure from one participant encourages others to share their experiences with confident members “breaking the ice” for others to gain confidence; and that supportive feedback can encourage participants to elaborate and provide additional detail [10]. Humor in focus group discussions has also been found to help establish and maintain this common ground and relationships within the group [6,11].

Some researchers argue that the complex social context of focus groups is often overlooked and rarely features in publications [12]. They argue a number of interrelated social contexts affect the quality of discussion and likelihood of disclosure within focus groups: associational, relational, status and conversational contexts. The physical place and its association to the participant as well as an individual’s association to others in the group are important—participants may focus their contribution on issues related to their commonality with the place or characteristics of other participants. The degree to which participants know each other i.e. their relational context is also considered to have an impact on the discussion. Some researchers advise grouping participants with common characteristics (gender, class, age, ethnicity and culture) to ensure that participants establish common ground [13]. Status within a group i.e. the relative positions of the participants in local or societal status hierarchies, such as workplace authority, gender, race, age, sexual identity, or social class will also impact on contributions made [12]. By the nature of most research methods, the researcher is part of the status context within which the discussion takes place. Key guides on facilitating focus groups advise it is essential that the moderator adopts a non-judgmental, non-evaluative approach and preferably shares the same characteristics as participants to reduce the impact of their status within the group [2,12,14,15]. During the group discussion views of participants may also change several times, influenced by the views of others and often whoever speaks first sets the tone and direction for the subsequent discussion [12]. Cultural norms about what is appropriate to discuss in a particular context can impact on the discussion and how a focus group is viewed (professional meeting versus counseling session) may produce different types of dialogue because in focus groups, like all research, participants may present themselves how they would like to be seen rather than how they really are. This social desirability may inhibit views—participants may be overly supportive of the views of other participants or the facilitator [2,16] or try presenting themselves in a good light [17].

Health panels are a focus group based approach to public involvement—a method of gathering the views of the public about health services or health issues in a local area. They evolved as a pragmatic solution to ensuring effective methods of local public involvement were in place in response to National Health Service policy changes in England [18-20]. In broad terms, they share many of the characteristics of focus groups—they are groups of people, brought together for a focused purpose, facilitated by a moderator, and discussion is recorded and transcribed. The main difference is that participants are recruited to the panel itself and not for a specific topic, remaining on the panel for three meetings and then “retiring”. This provides both a constant refreshing of panel members but retains some continuity of membership each time, creating a distinct social context. Although health panels enable many of the desirable focus group conditions to be met (non-evaluative facilitator and shared identity as associated with geography) by their design they do not group participants by other common characteristics (age, class, gender, status or experience).

There is considerable research on sensitive or “taboo” topics [21,22]. Focus group research on such topics generally comprise of participants with experience of the topic, e.g. stigma and schizophrenia [23] or sexuality and cancer [24], thereby attempting to control the social contexts recommended for focus groups. Although no prior knowledge of participants experiences on any given topic are known, health panels have also been used to tackle sensitive topics, e.g. resuscitation of patients, teenage conception, attitudes and barriers to seeking help for depression and stress related disorders [25]. Although there are regular national surveys [26], there is limited qualitative research published regarding public attitudes to depression and even less on the way in which people self-disclose depression in a public or group situation. I report in this article how disclosures of depression were made in the context of health panels.

2. METHODS

2.1. Data Collection

The Somerset Health Panels were made up of 12 separate groups meeting for two hours each, across Somerset, England. All were facilitated by an experienced independent researcher. Participants for the Somerset Health Panels were recruited to a quota sample to reflect the age and gender proportions of the total Somerset population. Trained recruiters visited areas that surrounded each panel and knocked on doors in the neighborhoods at different times of the day and at weekends to ensure that a wide range of potential participants could be reached. Recruiters explained the general aims of the panels, the types of topics discussed, what to expect, what would be required and, if the person was interested and fulfilled the quota they obtained consent.

The Somerset Health Panels discussed the topic “attitudes and barriers to accessing help for depression and stress related disorders” in the April/May 2001 round of meetings. The Somerset Health Panels research team (of which I was a member) within Somerset Health Authority developed the topic guide in collaboration with the independent facilitator. Meetings with key informants (representatives from mental health service providers and commissioners including voluntary organizations, the four Primary Care Trusts, the Health Authority and the Community Health Council) provided background information to assist in the development of the topic guide. Participants were informed that the topic for discussion was proposed by the Public Health Department of Somerset Health Authority following a survey of the prevalence of stress and depression in the Somerset population [27] and results would contribute to the planning and development of health services in Somerset. Participants were offered a small honorarium to cover expenses and transport arranged for those who required it to get to the venues (all local public non-healthcare venues e.g. village hall, library meeting room). It was anticipated that the topic might reveal many sensitive and personal experiences from participants, therefore the need for confidentiality was stressed at the beginning of each group and additional information in the form of leaflets about depression and local sources for additional information and support was made available to participants at the end of each group. Each focus group was audio taped and tapes were subsequently transcribed by an independent and experienced research transcription service.

National Health Service Research Ethics Committee approval was obtained when the Somerset Health Panels were established in 1994. Confirmation was obtained in 2006 that approval was not required for re-analysis of this data.

2.2. Participants

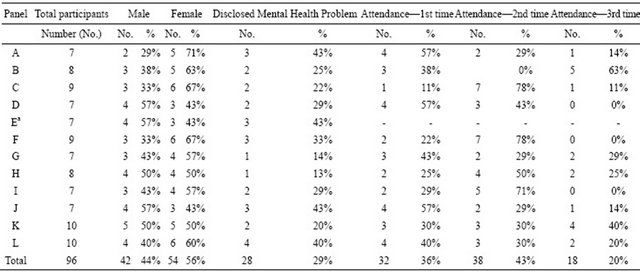

In total 96 participants attended the 12 panel meetings to discuss this topic (Table 1). Only gender and attendance history was collected: 44% (n = 42) of participants were male, 56% (n = 54) female. 36% (n = 32) of participants were attending a panel for the first time, 43% (n = 38) for the second time and 20% (n = 18) for the third and final time (attendance data was not available for one panel). No other demographic information was collected on participants.

2.3. Analysis

Analysis of the data was undertaken shortly after the data collection to produce a descriptive report to support future decisions about service development by the local health organizations [28]. I subsequently reanalyzed the transcripts specifically for this article as described below. I used QSR International’s NVivo 8 software to facilitate data management and analysis.

I first reviewed all transcripts to determine if any participants disclosed a personal (current or past) mental health problem. Qualitative and quantitative analyses were then undertaken. I undertook an inductive thematic analysis [29] to explore how disclosures happened and what impact the facilitator and other participants had on the disclosures. I reviewed transcripts in detail until no new themes emerged resulting in reviewing five transcripts which contained nine disclosures. I coded each transcript for: form of disclosure, impact of disclosure, participant roles, and facilitator affect. I asked two colleagues to review two of the same transcripts and we discussed the coding and interpretation to ensure the validity of my analysis. For each quote used within this article I have provided a reference to the panel the participant attended, the participant number and gender e.g. “A7f” refers to panel A, participant 7, female. I undertook content analysis of all transcripts to identify attendance history (i.e. participant attending for the first, second or third time), disclosure, and gender. I used ChiSquare tests (using Stata 10) to determine whether any of these factors increased the likelihood of disclosure.

3. RESULTS

Analysis demonstrated that participants self-disclosed their experience of depression in one of two ways. I have termed these two styles as “announcer” and “confessor”. Responses by others (the facilitator and other participants) had positive and negative impacts on self-disclosure. The issues of who discloses, how they disclose, what helps

Table 1. Participant characteristics.

aAttendance data was not available for panel E.

and hinders disclosure and the impact of the disclosure are each explored in turn below.

3.1. Who Discloses

During discussions 29% (n = 28; 19 female, 9 male) participants across the twelve health panels disclosed having, or having previously had, a mental health problem (Table 1). Although disclosure by women was higher (21% (9/42) men and 35% (19/54) of women disclosed a previous or current mental health problem) no significant difference was detected (χ2 = 2.16; df = 1; p = 0.14). Although likelihood of disclosure appeared to decrease with frequency of attendance (34% (11/32) of participants who attended for the first time disclosed a mental health problem compared to 24% (9/38) who had attended for the second time and 22% (4/18) who had attended for the third time; Table 1), no significant difference was detected (χ2 (Trend) = 1.056; df = 1; p = 0.30).

3.2. How Disclosures Are Made

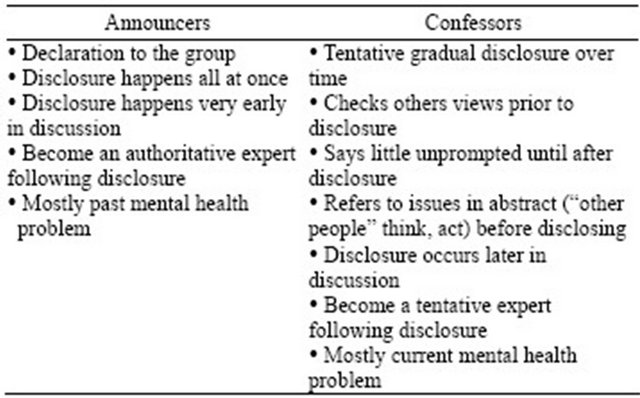

Disclosures had a range of features that could be distilled into two main styles—which I have termed “announcers” and “confessors”. These are two new conceptual categories and the characteristics of each style are summarized in Figure 1 and are explored below. The characteristics of the two styles emerged in the coding and themes that were derived from them but the clustering of those codes into the two styles was an insightful idea that was then retested against the data to confirm that as categories they really made sense.

“Announcers” disclosed by announcing to the group they had a mental health problem, not seeking reassurance or acceptance but to declare their status as expert in the discussion. These participants tended to disclose their mental health problem in the opening stages of the discussion. The following participant was the first person to speak after the facilitator’s introduction and provides an example to demonstrate these characteristics:

Figure 1. Characteristics of announcers and confessors.

“I’m quite happy to admit the fact that I’ve been diagnosed clinically as suffering from depression and stress in the past and take issue with the fact that you’re only talking about one subject cause you’re talking about two distinct illnesses, but if you’re talking about attitudes then the same prevails, and primarily it’s one of embarrassment that people don’t like to say ‘Oh dear, I have been actually diagnosed as being depressed or stressed’. I have, I am cured—so I think I can speak with a little bit of authority about attitudes and one of the first things that strikes you when you’re stressed or depressed is you don’t want to tell anybody because you’re frightened to, it’s as simple as that.” (H5m, 2nd attendance).

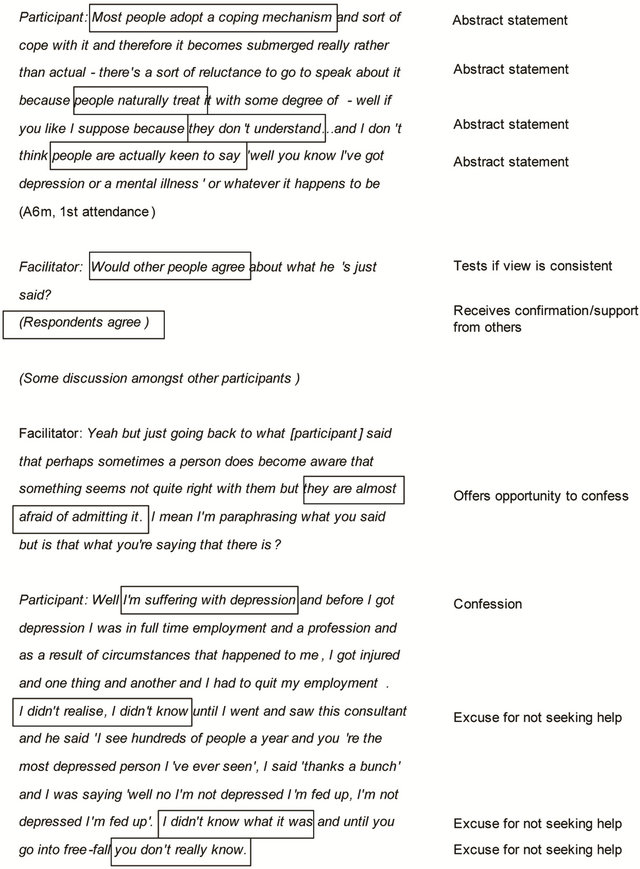

In contrast to “announcers” the pathway to disclosure for “confessors” was more complex. These participants tended to be speak less in the group prior to making their disclosure, generally only contributing when prompted by the facilitator. They tended to build up to disclosing their own mental health problem and used more general statements to test others attitudes, referring to “people think” or behavior of “others” first before talking about their personal experiences. Figure 2 provides excerpts from a transcript annotated to illustrate the key points in the pathway to disclosure as described above.

3.3. Factors that Supported and Inhibited Disclosure

A number of factors that supported or hindered disclosure during the discussions emerged from the data but all relate to a central theme of normalizing discussions about mental health problems. Normalizing events included: the facilitator introduction; attitudes expressed prior to any disclosure (including acknowledgment of stigma); reaction by the facilitator and other members to disclosures; response by the facilitator or others in the group to negative attitudes.

The facilitator opened each panel by describing the results of the county-wide survey that estimated one third of the population studied was suffering from stress or depression, providing all participants with the knowledge that mental health problems were common. Participants were then immediately asked if they were surprised by the results, which although generally resulted in a mixture of views rarely were those views combined with any negative attitudes toward people with a mental health problem. The acknowledgement by participants of potential stigma by others (but not by themselves) enabled negative attitudes to be discussed, thus facilitating disclosure. As seen above, positive normalizing statements were used by those who were building up to disclosure to gauge the attitudes of other participants. Similar statements were used by non-disclosing participants, providing support to those who would later disclose, for example:

Figure 2. Example of a confessor’s pathway to disclosure.

“People, people around us, everyone, we all make up society and we all have perceptions of things. We all respond to stresses in a different way so stress is a different thing for each person and I think another reason why it doesn’t surprise me. Something that could be very stressful say a death of a partner might—or the death of a friend may affect someone in a very different way to someone else. People have different ways of dealing with things”. (G6f, 2nd attendance)

Occasionally negative comments were also made, which clearly inhibited disclosure. The excerpt below shows the abstract statement stage of a confessor’s (participant (P1)) disclosure and the negative response from another participant (P2).

“P1: Well I’ve been surprised by people that I’ve known for a long while, jolly, happy people who’ve told me ‘Well it happened to me some years ago’, and I think ‘Oh wow!’ and you know, you talk to them about it and somebody I’ve known for a long while, a nice young man and this was last year and he was going through it and I couldn’t believe it because on the surface he was a really cheerful chap but he had a chat with my husband and I and you know, we sort of sympathize and everything and I was surprised when he did talk to us. We don’t bottle things up like we did. (D5f, 1st attendance)

P2: I’m sorry but I disagree with [P1]—I think people do try to hide it if they’ve got depression; it’s something they don’t want other people to know. They’d tell you if they’d got cancer or something like that but if they’re really suffering with depression I think they try and hide it as long as possible. For some reason they’re ashamed of it” (D7f, 1st attendance).

Participant 1 did not contribute again to the discussion for some time and the confession stage was therefore seemingly delayed by the challenge made by participant 2. Subsequent supportive and normalizing statements made by the facilitator and other members of the group ensured the negative comments did not prevent disclosure altogether.

3.4. Impact of Disclosure

In the majority of cases it was obvious to the other members of the group when a disclosure had occurred, even if on occasion it wasn’t immediately acknowledged. However, there were examples where a participant disclosed but their disclosure was hidden between general statements. Two examples of this are provided and annotated in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Redirection following disclosure.

In the first example, the participant made a general comment then referred to himself but it is unclear whether this was a joke or a disclosure, before he returned to making more general comments. In the second example, the participant made general comments, followed by a clear disclosure about themselves but then returns immediately to a general statement. In both cases, the general statement post-disclosure directed the subsequent group discussion away from acknowledging the disclosure which was not referred to again until much later in the group’s discussions.

Following disclosure, both “announcers” and “confessors” became informal “experts” in the group and also frequently provided peer support to each other or to those who subsequently disclosed. Both continued to have (announcers) or to develop (confessors) the confidence to offer their experiences to aide the discussion and “confessors” seemed to need less prompting to contribute post disclosure.

Following disclosures the reaction of others in the groups was generally positive. Follow-up questions by others encouraged the person disclosing to expand on their story and to contribute more. For example below:

“Participant (P) 1: Did you notice the other key word too—‘these people’—it’s not ‘these people’, it’s us, because I’ve got news for everybody here, you all suffer from stress and depression and it’s a question of degree and if there’s one of you round this table who can look me in the eye and say you haven’t cried, I’ll call you a liar. (C5m, 2nd attendance).

P2: All the time! (C7f, 2nd attendance, non-discloser).

P1: What do you think makes you cry, it’s depression, it’s just a question of degree.

P2: Cause you’ve got nobody to talk to.

P1: Exactly, have you sprained your wrist or have you broken your arm, that’s the difference between crying and clinical depression”.

On most occasions, the facilitator reacted to disclosures by broadening discussion back to the wider group. In most cases (although not all) the facilitator acknowledged the disclosure immediately before seeking wider views as in the example below.

“Participant: I don’t agree because I think everybody’s been perhaps not as bad as [other participant], but I’ve been pretty low myself, I’ve had times when I wouldn’t have answered the door and pretend I wasn’t there and I’ve been pretty low, so I think most people have had times like that and would help (C9f, 2nd attendance).

Facilitator: I know people have said that it’s very difficult for people… I don’t know how quickly but you certainly went and found help, but we have talked about the fact that it is perhaps difficult for people with depression or who feel very stressed to find help, so I mean where do you think their first port of call should be?”

This approach seemed to deflect discussion away from the discloser temporarily before the facilitator returned to make reference to the disclosure later on in the discussion. Particularly for “confessors” it appeared to enable them to assess the impact of their disclosure on the others in the group. Because there was rarely surprise by the facilitator or the others in the group perhaps this approach enabled the “confessors” to gain the confidence needed to become “experts”.

4. DISCUSSION

The analysis provides new information which will be of significance to those who work with group-based research methods and/or with people with stigmatized health conditions including mental illness and depression in particular. I have conceptualised two main styles by which people disclose personal stories—“announcers” and “confessors”. In addition, a number of key factors that help or hinder disclosure were also identified—the use of normalizing comments (by disclosers, other participants and the facilitator); the impact of setting the tone; the impact of others responses to disclosures and partial disclosures. I have also demonstrated that health panels can be used as an effective method to discuss sensitive topics, in this case attitudes to stress, depression and help-seeking.

As a facilitator it is difficult to predict at the outset who within a group is likely to disclose or not and in this research it was not possible to identify any previously known participant characteristics (i.e. gender or attendance frequency) that increased the likelihood of disclosure. Although a higher percentage of women disclosed than men in these panels, which is consistent with other research [30], no significant difference was able to be detected here. It is generally recommended that focus groups should be avoided when participants are not compatible or unless they are comfortable with each other [31], however it might be argued that health panels overcome this through establishing membership that is semi-stable and therefore that an increased likelihood of disclosure would be correlated with an increased frequency of attendance. In fact, the numbers were too small to detect any statistically significant relationship. It might have been useful to know if other demographic factors impacted on disclosure but these were not collected at the time as they were not considered necessary for the original health panel purpose.

Signals provided during discussion relating to how people disclose indicate that the facilitator plays a critical role in nurturing the environment to make disclosures happen. It has been proposed that participants have a role as they can “break the ice” for others to speak [10]. In this study, “announcers” were found to readily disclose although “confessors” were found to be affected much more by the other participants and the facilitator. The tone for the discussion was set by the facilitator by providing a key message that suffering from stress and depression was very common. The importance of this introduction to state the cultural norm and set the tone as suggested by others [12], clearly impacted on the discussion and immediate disclosure by participants in this study also. The use of normalizing statements by the discloser enables them to check the attitudes of others, and use of similar statements by other participants provides evidence that the group is likely to be accepting of a disclosure. Normative belief is a key factor in The Theory of Planned Behavior [32] which provides a model to explain how attitudes relate to behavior. In this study it featured as a key factor in how readily the desire to disclose resulted in actual disclosure. It provides important insights: that the experienced facilitator must look out for hidden, partial disclosures and probe participants to expand; that they can normalize disclosure through setting the tone of the discussion and in their response; and can promote the safety of the group by setting of ground rules or in their response to stigmatizing language or comments. Some researchers suggest it is not just the facilitator and other participants that influence discussion, but that there are other absent voices in focus groups— absent speakers (when participants talk about what others think), the voice of common sense (when participants talk generically or there is a “distant discourse”), assumed shared knowledge, and the internal voice [33]. This is consistent with a dialogic perspective which recognizes that what is said is influenced not only by what is said during the group but also by what has been said in the past (before the group) and in anticipation of what might be said/thought in the future [34]. Additional research is now needed to test whether the concepts of “announcers” and “confessors” are present in other data and then to further explore the dynamics of disclosure within group dialogue.

Researchers tend to report fragments of transcripts from individuals to illustrate “what” participants thought rather than including the context and interaction between participants to demonstrate “why” and “how” they thought [4]. Others believe it is the study of the socially shared knowledge that is of most interest, in the dynamics of the dialogues created in the context of the focus group and in exploring the psychology of language and communication [33]. Therefore it is suggested that to study these dynamics focus groups should ideally be designed with this in mind [35]. This article focuses on how people thought about depression within the context of an applied research method—the health panel, which was designed with the main aim of capturing what people thought about the topic so that it could shape local health services.

I have demonstrated that it is possible to look at discourse interactions even though this was not originally the main research goal. What has not been possible to consider in this article is the “why”—why people choose to self-disclose personal and often intimate information about themselves to relative strangers in a non-therapeutic setting. In this study the pay off for disclosing in the health panel context appeared to be that disclosers were then able to proclaim their expertise on the topic. However, data was not collected from participants on what motivated them to disclose their experiences at all, or indeed what prevented them.

This study has important messages for wider social interactions relating to depression and other personal disclosures. The lifetime likelihood of suffering from depression is calculated to be up to 50% [36] and 75% of those who do seek professional help report they had been prompted to do so by someone else [37]. Therefore, at some stage in the help-seeking process the person will take the first step by disclosing their problem to someone else. The factors that inhibit or support disclosure evident from this study could be considered to be similar in other social situations. The response to any attempt to disclose or “test the water” using general statements will probably, particularly for “confessors”, impact on the likelihood of disclosure in the same way as it did in the focus group situation for example. Health services should train their frontline health professionals to use general normalizing statements and look out for pre-disclosure indicators as outlined in this article in order to increase the likelihood of a disclosure of potentially stigmatising health conditions like depression.

5. CONCLUSION

In conclusion, the health panel method created an environment where participants were able to disclose personal and sensitive stories and within this article I have demonstrated that health panels can be used successfully for the discussion of sensitive topics. I have presented two new conceptual categories of “announcers” and “confessors” which are an addition to the current literature on disclosure and more broadly I have begun to provide an insight into the pathways of disclosure. Identification of “announcers” and “confessors” and the factors that inhibited or supported disclosures are relevant for any focus group based research on sensitive topics (or on seemingly non-sensitive topics where disclosure occurs) and relevant to any health issue, not just mental health.

6. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I thank Dr. David Evans and Dr. Maz Morris for their invaluable support and comments in the development of this article.

![]()

![]()

REFERENCES

- Wilkinson, S. (1998) Focus groups in health research: Exploring the meanings of health and illness. Journal of Health Psychology, 3, 329-348. doi:10.1177/135910539800300304

- Krueger, R.A. and Casey, M.A. (2000) Focus groups: A practical guide for applied research. Sage Publications Inc., Thousand Oaks.

- Kitzinger, J. (1995) Qualitative research: Introducing focus groups. British Medical Journal, 311, 299-302. doi:10.1136/bmj.311.7000.299

- Kitzinger, J. (2004) The methodology of focus groups: The importance of interaction between research participants. Sociology of Health and Illness, 16, 103-121. doi:10.1111/1467-9566.ep11347023

- Lehoux P., Poland B. and Daudelin, G. (2006) Focus group research and “the patient’s view”. Social Science and Medicine, 63, 2091-2104. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.05.016

- Williams, J.K. and Ayres, L. (2007) “I’m like you”: Establishing and protecting a common ground in focus groups with Huntington disease caregivers. Journal of Research in Nursing, 12, 655. doi:10.1177/1744987107083514

- Edmunds, H. (1999) The focus group research handbook. NTC Business Books, Chicago, 7-8.

- Frey, J.H. and Fontana, A. (1993) The group interview in social research. In: Morgan, D.L., Ed., Successful Focus Groups: Advancing the State of the Art. Sage, Newbury Park.

- Hyden, L.-C. and Bulow, P.H. (2003) Who’s talking: Drawing conclusions from focus groups-some methodological considerations. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 6, 305-321. doi:10.1080/13645570210124865

- Frith, H. (2000) Focusing on sex: Using focus groups in sex research. Sexualities, 3, 275-297. doi:10.1177/136346000003003001

- Wilkinson, C.E., Rees, C.E. and Knight, L.V. (2007) From the heart of my bottom: Negotiating humor in focus group discussions. Qualitative Health Research, 17, 411- 422. doi:10.1177/1049732306298375

- Hollander, J.A. (2004) The Social Contexts of Focus Groups. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, 33, 602- 637. doi:10.1177/0891241604266988

- Morgan, D.L. (1995) Why things (sometimes) go wrong in focus groups. Qualitative Health Research, 5, 516-523. doi:10.1177/104973239500500411

- Morgan, D.L. (1997) Focus groups as qualitative research. Sage Publications Inc., Thousand Oaks.

- Greenbaum, T.L. (2000) Moderating focus groups: A practical guide for group facilitation. Sage Publications Inc., Thousand Oaks, 37-38.

- Aronson, E., Ellsworth, P.C., Carlsmith, J.M. and Gonzales, M.H. (1990) Methods of research in social psychology. McGraw-Hill, NewYork.

- Goffman, E., (1959) The presentation of self in everyday life. Doubleday Anchor, New York.

- Coe, N. (2012) Health panels: The development of a meaningful method of public involvement. Policy Studies, 33, 263-281. doi:10.1080/01442872.2012.694267

- Bowie, C., Richardson, A. and Sykes, W. (1995) Consulting the public about health service priorities. British Medical Journal, 311, 1155-1158. doi:10.1136/bmj.311.7013.1155

- Department of Health (2008) Real involvement: Working with people to improve health services. Crown Copyright, London.

- Lee, R.M. (1993) Doing research on sensitive topics. Sage Publications Ltd., London.

- Lee, R.M. and Renzetti, C.M. (1993) The problems of researching sensitive topics. In Renzetti, C.M. and Lee, R.M., Eds., Researching sensitive topics. Sage Publications Inc., Thousand Oaks.

- Schulze, B. and Angermeyer, M.C. (2003) Subjective experiences of stigma. A focus group study of schizophrenic patients, their relatives and mental health professionals. Social Science & Medicine, 56, 299-312. doi:10.1016/S0277-9536(02)00028-X

- Bruner, D.W. and Boyd, C.P. (1999) Assessing women’s sexuality after cancer therapy: Checking assumptions with the focus group technique. Cancer Nursing, 22, 438- 447. doi:10.1097/00002820-199912000-00007

- Coe, N. (2009) Exploring attitudes of the general public to stress, depression and help seeking. Journal of Public Mental Health, 8, 21-31. doi:10.1108/17465729200900005

- Department of Health (2003) Attitudes to mental illness 2003 report. Crown Copyright, London.

- Oliver, M.A., Pearson, N., Coe, N. and Gunnell, D. (2005) Help seeking behaviour in men and women with common mental health problems: Cross-sectional study. British Journal of Psychiatry, 186, 297-301. doi:10.1192/bjp.186.4.297

- Bellamy, J. and Purvis, J. (2001) The somerset health panels: Report of the 20th round of panels held in April/May 2001. Somerset Health Authority Internal Report.

- Braun, V. and Clarke, V. (2006) Using thematic analysis in Psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3, 77-101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Dindia, K. and Allen, M. (1992) Sex differences in selfdisclosure: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 112, 106-124. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.106

- Krueger, R.A. (1998) Moderating focus groups. In Krueger, R.A. and Morgan, D.L., Eds., The focus group kit. Sage Publications Inc., Thousand Oaks.

- Ajzen, I. (1991) The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50, 179-211. doi:10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

- Markova, I., Linell, P., Grossen, M. and Orvig, A.S. (2007) Dialogue in focus groups: Exploring socially shared knowledge. Equinox Publishing Limited, London.

- Bakhtin M.M. (1981) The dialogic imagination. In: Emerson, C. and Holquist, M., Trans., University of Texas Press, Austin.

- Morgan, D.L. (2010) Reconsidering the role of interaction in analyzing and reporting focus groups. Qualitative Health Research, 20, 718-722. doi:10.1177/1049732310364627

- Kessler, D., McGonagle, K.A., Zhao, S., Nelson, B., Hughes, M., Eshleman, S., Wittchen, H.U. and Kendler, K.S. (1994) Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSMIII-R psychiatric disorders in the United States. Results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry, 51, 8-19. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950010008002

- Vogel, D.L., Wade, N.G., Wester, S.R., Larson, L. and Hackler, A.H. (2007) Seeking help from a mental health professional: The influence of one’s social network. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 63, 233-245. doi:10.1002/jclp.20345