Applied Mathematics

Vol.06 No.05(2015), Article ID:56709,16 pages

10.4236/am.2015.65079

Functional Weak Laws for the Weighted Mean Losses or Gains and Applications

Gane Samb Lo1,2, Serigne Touba Sall1,3, Pape Djiby Mergane1

1LERSTAD, Université Gaston Berger de Saint-Louis, Saint-Louis, Sénégal

2LSTA, Université Pierre et Marie Curie, Paris, France

3Ecole Normale Supérieure, Dakar, Sénégal

Email: pdmergane@ufrsat.org

Copyright © 2015 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received 22 February 2015; accepted 24 May 2015; published 27 May 2015

ABSTRACT

In this paper, we show that many risk measures arising in Actuarial Sciences, Finance, Medicine, Welfare analysis, etc. are gathered in classes of Weighted Mean Loss or Gain (WMLG) statistics. Some of them are Upper Threshold Based (UTH) or Lower Threshold Based (LTH). These statistics may be time-dependent when the scene is monitored in the time and depend on specific functions w and d. This paper provides time-dependent and uniformly functional weak asymptotic laws that allow temporal and spatial studies of the risk as well as comparison among statistics in terms of dependence and mutual influence. The results are particularized for usual statistics like the Kakwani and Shorrocks ones that are mainly used in welfare analysis. Data-driven applications based on pseudo-panel data are provided.

Keywords:

Empirical Process, Time Dependent Process, Weak Theory, Risk Measures, Poverty Index, Loss Function, Economic Welfare

1. Introduction and Motivation

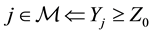

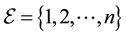

In many situations and many areas, we face the double problem of estimating the risk of lying in some marked zone and, at the same time, the cost associated with it. To fix ideas, we may be interessed in estimating the immunocompromised patients number , and the size of the set

, and the size of the set  of infected people, in some population

of infected people, in some population . At the same time, we know that the severity of the infection is measured by the viral load

. At the same time, we know that the severity of the infection is measured by the viral load  expressed in RNA copies per milliliter of blood plasma. The cost of treatement, for example a course of chemotherapy, heavily depends on the viral load. If one has to treat all the patients, there is a cost to pay for each treatment, which is a cost function

expressed in RNA copies per milliliter of blood plasma. The cost of treatement, for example a course of chemotherapy, heavily depends on the viral load. If one has to treat all the patients, there is a cost to pay for each treatment, which is a cost function . Facing these two problems at the same time, comparing two different populations or monitoring the evolution of the global situation should be based on the couple

. Facing these two problems at the same time, comparing two different populations or monitoring the evolution of the global situation should be based on the couple  rather than on which is commonly called the HIV/AIDS adult prevalence rate, on what is based international comparison. In order to make a workable statistic, consider a sample of individuals

rather than on which is commonly called the HIV/AIDS adult prevalence rate, on what is based international comparison. In order to make a workable statistic, consider a sample of individuals  drawn for

drawn for  and measure the viral load

and measure the viral load  for each

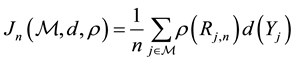

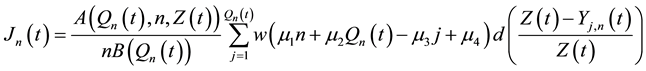

for each . A general comparative statistic should be of the form

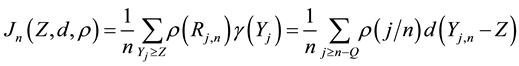

. A general comparative statistic should be of the form

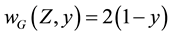

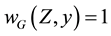

Since comparisons over the time are based on this index, one will be interested in putting more or less emphasis on the more infected or not, in terms of viral load. This is achieved by affecting a weight  to

to  as a monotone function of the rank

as a monotone function of the rank  of

of  in the sample. For an increasing

in the sample. For an increasing , it is paid more attention to less infected while the contrary holds for a decreasing one. This leads to statistics like

, it is paid more attention to less infected while the contrary holds for a decreasing one. This leads to statistics like

It is also known that the viral load is detectable only above a threshold of value

and

We may decide to concentrate on the very expansive chemotherapy courses due to financial pressure. In that case, we change the threshold to

Such statistics are also used in insurance theory. Suppose that one insurance company receives

and to choose a distorsion function

where

In poor countries, an individual is considered as a poor one when his income

is the total number of poor people in the sample, while

here depends on the relative poverty gap

may be called a General Poverty Index (GPI). The same form may also be used in medical science when dealing with vitamine (say vitamine D) deficiency. In this case,

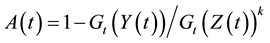

We see from the lines above that (1) is a very general statistic, which works in various fields, with losses or gains dependent on the meaning of the cost function

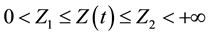

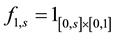

When we have time-dependent data, over the time

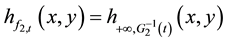

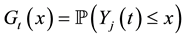

In the case where

The choice of

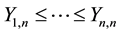

Finally, taking into account various forms of (1) in the literature, the following form of threshold-based weighted mean loss seems to be a general one

or the following

depending on whether we handle loss (with

From a mathematical point of view, the asymptotic behaviors of the two forms radically differ although the writing seems symetrical. The reason is that for the first, the random variables used in (4) are bounded and the asymptotic handling is much easier. As for (5), we should face heavy tail problems and further complications may arise.

This paper is aimed at offering a full functional weak theory according to the most recent setting of such theories as stated in [5] . Particularly, we are interested here in the time-dependent investigation of (4), and next the functional weak theory in

Consider for a while that

where

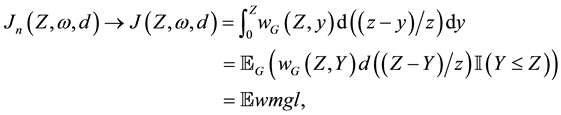

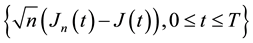

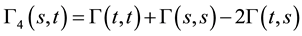

To be able to base statistical tests of such results, we may be interested in finding the asymptotic law of

However, we still need to handle longitidunal data, where the risk situation is analysed over a continuous period of time

with

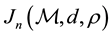

Instead of analysing such UTB WMLG for some specific functions

This paper is aimed at settling the uniform weak convergence of such statistics, which is the asymptotic theory of the time-dependent poverty measures (6), in the space

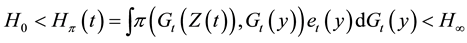

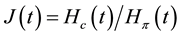

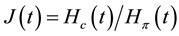

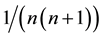

An important application is the statistical estimation of the Relative Mean Loss Variation (RMLV) from time

by confidence intervals where

We will need a number of hypotheses towards an adequate frame for our study. These hypotheses may appear severe and numerous, at first sight, but most of them are natural and easy to get. We first need the following shape conditions for the WMLG measures themselves. The letter S in the hypotheses names refers to shape con- ditions.

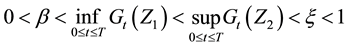

(HS1) There exist functions

where

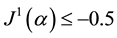

(HS2)

(HS3) There exists a function

We will require other assumptions depending on the regularity of the functions

(HR1) The bivariate functions

(HR2) For a fixed

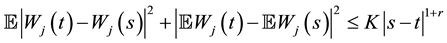

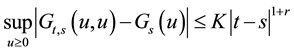

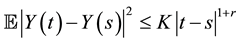

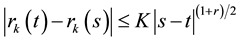

(HR3) There exist

and

Our final achievement is that, when putting

law of

enables the statistical uniform estimates of

2. Our Results

Our results will rely on the representation of Theorem [11] , which in turn will need the following assumptions.

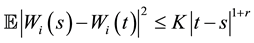

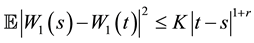

(HL1) There exist

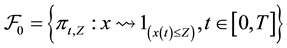

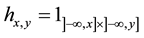

(HL2) The subclass

tinuous functions, is a

where, for any

Finally let us denote

(HL3) For any

(HL4)

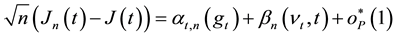

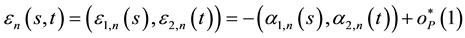

Theorem 1 Suppose that (HS1)-(HS2), (HR1)-(HR3) and (HL1)-(HL4) hold. Put

and

Define

and

Then we have, uniformly in

with

and

Suppose that (HS3), (HR1)-(HR3) and (HL1)-(HL4) hold. Then, (10) holds with

This theorem expresses our studied time-dependent statistics as the sum of a functional empirical process and the stochastic process (11). It will be seen, for a fixed time, that

function) and then of empirical process

Now, we use these tools to give first, general laws for the WMLG statistic below and then for the Kakwani class of indices in Section 2.2 and for the Shorrocks-Thon indices in Section 3. We finish by a special study of the absolute and the relative poverty changes in Section 4.

While we deal with the general index and we use the outcomes of Theorem 1, we adopt the following writing:

where

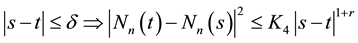

(HT1) For

(HT2) For

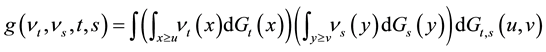

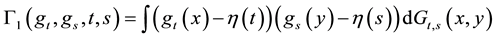

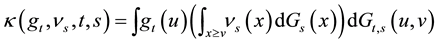

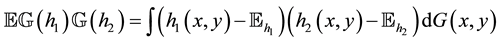

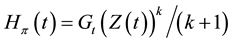

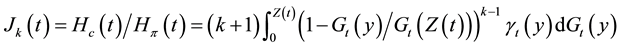

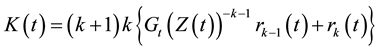

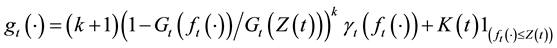

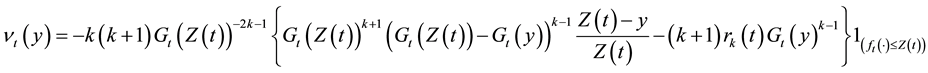

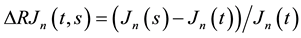

In order to define our last assumption, we need the following functions:

and

with, by convention,

(HT3) If there is a universal constant

We are now able to give our general main result.

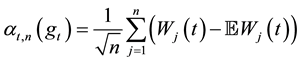

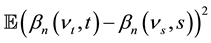

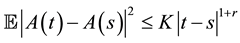

Theorem 2 Assume the conditions of Theorem 1 hold and that (HT1)-(HT3) are satisfied. Then the stochastic process

with

and

with

and

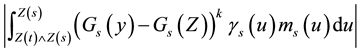

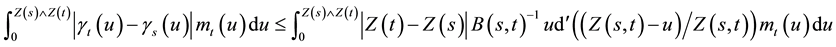

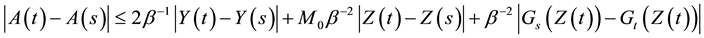

Proof. We have to do three things. First, we show that

Since the assumptions of Theorem 1 hold, we have the representation (10). Put

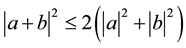

First (HT2) and (HT2) yield, for each

and hence, by repeated use of

We remind again that

find in [12] , that

where

Thus

and

where the

Now let, for each

and

Now, let

uniformly in

where

We have

for

But

pirical processes). Thus putting

in

Further, for

and for

Now, by using the Skorohod-Wichura-Dudley Theorem, we are entitled to suppose that we are on a probability space such that

Now, since the functions

One easily proves that

is a Gaussian random variable since the second term is a Riemann integral, which is a limit of finite linear com- binations of Gaussian random variables. Thus

2.1. Special Cases

Since the results are stated in a more general form and may appear very sophisticated, it seems necessary to show how they work for common cases. We apply our results to two key examples in Welfare analysis: the class of Kakwani’s and Shorrocks’ statistics. These two examples are particularly interesting since they put the emphasis on the less deprived individuals within the whole population (with weight

2.2. The Kakwani Case

We are now applying the general results to the Kakwani WMLG statistics of parameter

The way we are using here is to be repeated for any particular index. For instance, the results in [9] and [10] may be rediscovered in this way. In this specific case, we turn the hypotheses (HT1) and (HT2) on

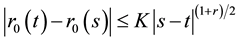

(H0) For

(H1) There exists a positive function

and

(H2) For

and

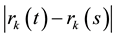

(H3) For

We check, in the Kakwani case, that the representation of Theorem 1 holds with

so that

Next

and then

where

For

and

we will get the representation

with

Theorem 3 Let (HL1), (HL3), (HL4), (H0)-(H3) hold. Then

Proof. We begin to remark that (H3) ensures that

3. The Shorrocks-Thon-Like Case

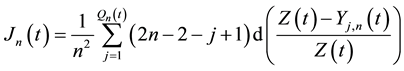

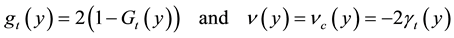

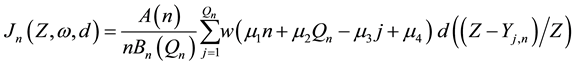

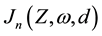

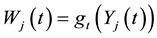

We apply our results to the Shorrocks-Thon WMLG statistics measures defined by

This is the Thon index. One obtains the Shorrocks one by replacing

Here again

under the same hypotheses (HL1)-(HL4) and (H0)-(H3)

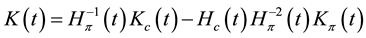

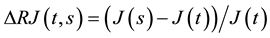

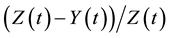

4. Estimation of the WLMG Statistic Variation

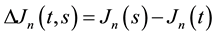

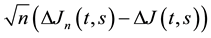

Although they are very expensive to collect, longitudinal data are highly preferred for adequate estimate of the absolute index variation

periods t and s and the associate relative WMLG variation

natural estimators are of course

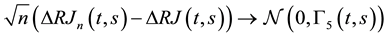

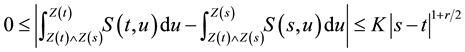

Theorem 4 Under the assumptioms of Theorem 1 or Theorem 2,

where

where

with

The proof is straightforward. We also might consider the convergence of

Gaussian process

An important application of the second part of this theorem is related to checking the achievement of specific goals. One may, within a national or regional strategy, whish to have some deprivation limited to some extent. For example, the UN has assigned a number of goals, named Millennium Development Goals (MDG), to its members. We are concerned here by one of them. Indeed, it is whished to halve the extreme poverty in the world in year

where

4.1. Datadriven Applications and Variance Computations

We apply our results in Economics and Welfare analysis. Especially, we consider the household surveys in Senegal in 2011 (ESAM II) and in 2006 (EPS) from which we construct pseudo-panel data and apply our results.

4.1.1. Variance Computations for Senegalese Data

We apply our results to Senegalese data. We do not really have longitudinal data. So we have constructed pseudo-panel data of size

When constructing pseudo-panel data, we get small sizes like

Before we present the outcomes, let us say some words on the packages. We provide different R script files at http://www.ufrsat.org/lerstad/resources/sallmergslo01.zip.

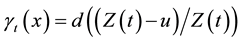

The user should already have his data in two files data1.txt and data2.txt. The first script file named after gamma_mergslo1.dat provides the values of

4.1.2. Analysis

First of all, we find that, at an asymptotical level, all our inequality measures and poverty indices used here have decreased. When inspecting the asymptotic variance, we see that for the poverty index, the FGT and the Kakwani classes respectively for

Table 1. Variations of the poverty indices.

5. Conclusion

We obtained asymptotic laws of the UTB WMLG statistics with in mind, among other targets, the uniform estimation of the variation

References

- Lo, G.S. (2013) The Generalized Poverty Index. Far East Journal of Theoretical Statistics, 42, 1-22. http://pphmj.com/journals/fjst.htm

- Artzner, P., Delbaen, F., Eber, J.M. and Heath, D. (1999) Coherent Measures of Risk. Mathematical Finance, 9, 203- 228. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1467-9965.00068

- Sen, A.K. (1976) Poverty: An Ordinal Approach to Measurement. Econometrica, 44, 219-231. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1912718

- Zheng, B. (1997) Aggregate Poverty Measures. Journal of Economic Surveys, 11, 123-162. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1467-6419.00028

- van der Vaart, A.W. and Wellner, J.A. (1996) Weak Convergence and Empirical Processes With Applications to Statistics. Springer, New York.

- Shorrocks, A.F. (1995) Revisiting the Sen Poverty Index. Econometrica, 63, 1225-1230. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2171728

- Thon, D. (1979) On Measuring Poverty. Review of Income and Wealth, 25, 429-440. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-4991.1979.tb00117.x

- Kakwani, N. (1980) On a Class of Poverty Measures. Econometrica, 48, 437-446. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1911106

- Sall, S.T. and Lo, G.S. (2009) Uniform Weak Convergence of the Time-Dependent Poverty Measure for Continuous Longitudinal Data. Brazilian Journal of Probability and Statistics, 24, 457-467. http://dx.doi.org/10.1214/08-BJPS101

- Lo, G.S. and Sall, S.T. (2009) Uniform Weak Convergence of Non Randomly Weighted Poverty Measures for Longitudinal Data. 57th ISI Session.

- Lo, G.S. and Sall, S.T. (2010) Asymptotic Representation Theorems for Poverty Indices. Afrika Statistika, 5, 238-244.

- Lo, G.S. (2010) A Simple Note on Some Empirical Stochastic Process as a Tool in Uniform L-Statistics Weak Laws. Afrika Statistika, 5, 245-251.

- Shorack, G.R. and Wellner, J.A. (1986) Empirical Processes with Applications to Statistics. Wiley-Interscience, New York.

Appendix

Put

with

and

We have first to prove that for

Based on the expression of

for

and

This would help to conclude with the

Let us establish (14). We have

where

Now we show (15)

ince

Further

and, since

where

From (24)-(26), we conclude that

and for

and

with

and

less than

and

By (H2), A is less than

for

which proves (15). Let us finally prove (16). We have by (H2), for a fixed

for some constant

with

and

and then (16) holds.

By putting together (14), (15) and (16) and by repeatedly using the

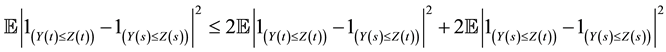

Now we have to establish that

Put

with

Then by (H0)-(H3) and the

Next

and

with

and

Then by (H2)

and

Next, by putting

where

By similar methods, we get

By combining all that precedes, we get (27), which together with (21) establishes by the

Now we have to prove that

We only sketch this second part. Let us consider

and

By (14),(15) and the decomposition of

Furthermore

We then get

Then

Now

with

Then

Since

Moreover, one easily shows by the (H0)-(H3), with similar techniques used when handling

Thus

.

.