International Journal of Clinical Medicine

Vol. 3 No. 7A (2012) , Article ID: 26348 , 18 pages DOI:10.4236/ijcm.2012.37A136

Qualitative Research on Emergency Medicine Physicians: A Literature Review

![]()

1SkejSim Centre for Medical Simulation and Training, Aarhus University, Aarhus, Denmark; 2Centre for Medical Education, Aarhus University, Aarhus, Denmark.

Email: paltved@dadlnet.dk

Received October 11th, 2012; revised November 28th, 2012; accepted December 12th, 2012

Keywords: Emergency Medicine; Emergency Department; Review; Qualitative Research; Interview; Observation

ABSTRACT

Aim: This study aims to review the qualitative research studying Emergency Medicine (EM) physicians in Emergency Departments (ED). Background: Qualitative research aims to study complex social phenomena by other means than quantification often through verbal or observational investigation. EM is a highly complex medical and social environment that has been investigated through qualitative methodologies. A literature review is needed to show what qualitative studies illuminate about EM and why this work is important to develop EM as a complex organizational and communicative practice. Methods: Electronic databases of English peer-reviewed articles were searched from 1971 to 2012 using Medline through PubMed and PsychINFO. This search was supplemented with hand-searches of Academic Emergency Medicine and Emergency Medicine Journal from 1999 to 2012 and cross references were reviewed. The key words used were emergency medicine, qualitative, ethnography, observation, interview, video, anthropology, simulation, and simulation-based. Results: 820 papers were identified and 46 studies were included in this review. This literature review found that the reviewed qualitative studies on EM physicians were designed using the following strategies of inquiry: Ethnography, mixed methods, action research, grounded theory, phenomenology, content analysis, discourse analysis, and critical incident analysis. The reviewed studies were categorized into four main themes: Education and training, communication, professional roles, and organizational factors, and into 12 sub-themes. Conclusion: The strength of qualitative research is its ability to grasp and operationalize complex relations within EM. Although qualitative research methodologies have gained in rigor in recent years and few researchers would question their value in studying complex medical and social phenomena, rigorous design in qualitative studies is needed. Qualitative research studies that stick with one strategy of inquiry that they follow closely are likely to yield more valid studies.

1. Introduction

Emergency medicine (EM) is performed by emergency physicians collaborating with other health professionals in highly complex practices that need to be researched through innovative means. Qualitative research might be particularly relevant to EM for at least three reasons. First, it is apt at illuminating processes pertaining to physicians’ thinking, feeling and acting as EM physicians. Second, qualitative research might be useful to capture EM organizational and team processes as complex medical and social practices [1]. Yet qualitative research has probably more often been used in medical education research and research on critical patient care [2-4] than to emergency care [5-8]. Third, qualitative research can lead to theory development hopefully with clinical or organizational implications for EM and Emergency Departments (ED). But research is needed that reviews qualitative research in EM and critically appraises qualitative research papers. However, the critical appraisal of qualitative research may be difficult because there is no single standard for carrying out qualitative research and hence qualitative research varies according to the applied methodologies or strategies of inquiry. The point is that achieving a nuanced understanding in this field is fairly complex. Furthermore thorough assessment of qualitative research is an interpretive act that requires informed reflective thought rather than a simple application of a scoring system [9]. A review of qualitative research in EM is relevant because it might enhance emergency care through in depth descriptions of contextual health care. And by moving beyond description and emphasizing the development of new concepts and theories, qualitative researchers can help to unpack the processes surrounding EM care and explain “how, why and what” is going on [10]. Thus it might inform practice, prevent errors and enhance patient safety [11,12], and also add to a deeper understanding of EM as a social practice.

2. Aim

This study aims to review the literature on qualitative research of health professionals involving EM physicians in ED.

3. Review Methodology

3.1. Study Design

A literature search in the medical and social sciences literature domains was carried out. Electronic databases were searched from 1971 to 2012. This study utilized Medline (through PubMed) and PsychINFO. Access strategies included the MeSH search term Emergency Medicine combined with the following keywords: qualitative, ethnography, observation, interview, video, anthropology, simulation, and simulation-based. Searches were run in September and October 2012.

3.2. Search Strategy

All English-language articles published in peer-reviewed journals from 1971 to 2012 were included in the search. In a first step, titles and abstracts of all 820 papers identified using the database searches were screened by the first author to ascertain whether the studies were designed with a qualitative methodology in EM and/or ED. In a second step, the exclusion criteria were applied, leading to retrieval of full text papers to be considered for inclusion. Full text articles were also retrieved when there was insufficient information in the abstract. The full text of selected articles was retrieved whenever possible.

In a third step, recognizing that electronic indexing can be unreliable [13,14], a hand search of all editions of the key journals Academic Emergency Medicine and Emergency Medicine Journal from 1999 to September 2012 was performed. This period was chosen due to the previously identified papers which were published from 1999 to 2011. Titles suggesting a qualitative approach that had not already been identified were obtained for examination of abstract and subsequently for full text if the abstract was found relevant. 26 papers were identified during this search and in total 46 articles were agreed for inclusion and analysis. From all the full text articles retrieved, reference lists were used to identify and potentially include additional papers not discovered during the initial search.

The retrieved abstracts were independently read by the two researchers to determine whether a full text article should be retrieved. The full text article was obtained if the abstract suggested that the study was a qualitative research study in the field of EM or ED’s and did not meet the exclusion criteria.

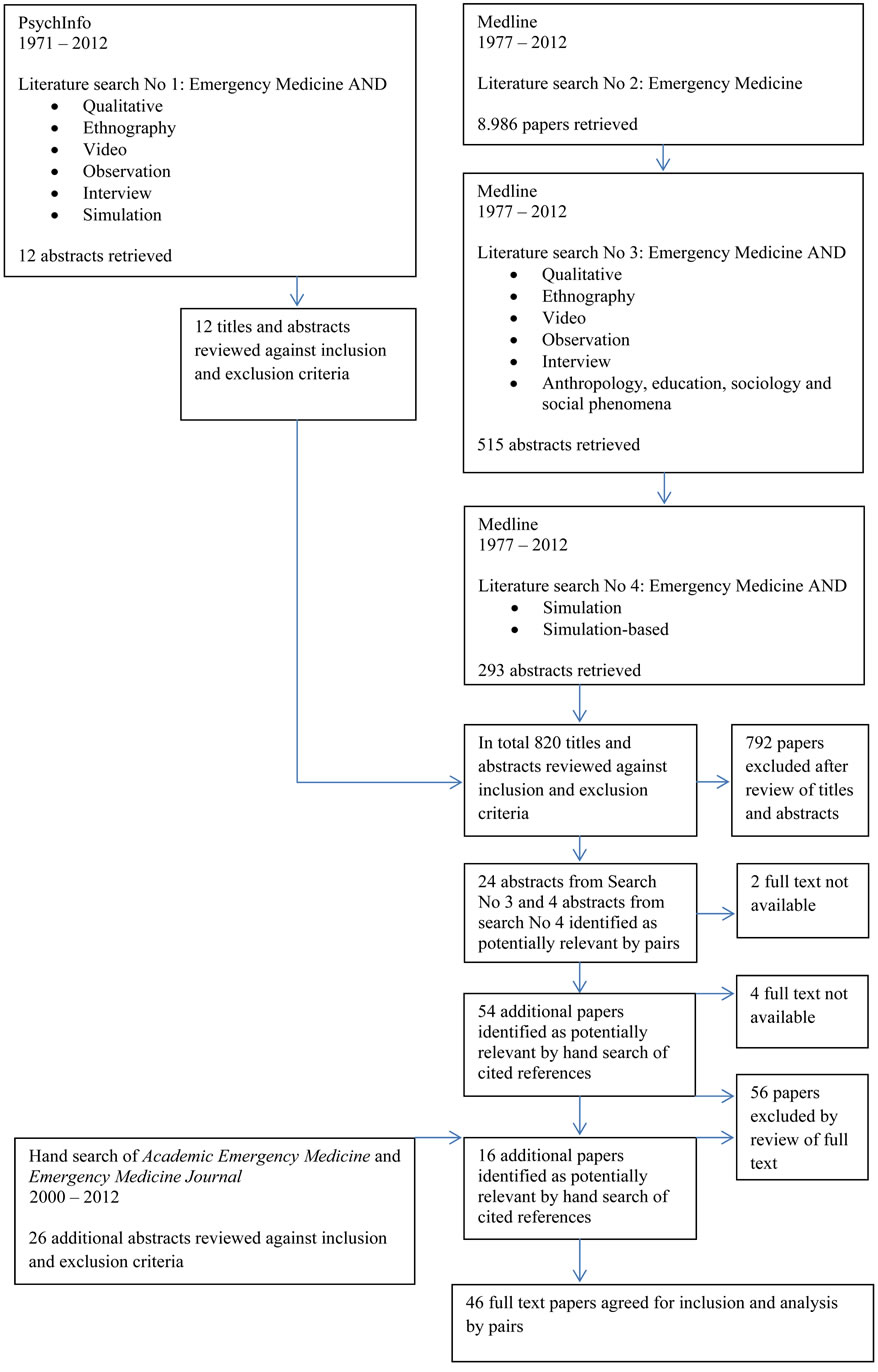

Figure 1 provides an overview of the process of identifing the articles included in this review. From here it can be seen that 46 papers were agreed for analysis and a total of 56 articles were excluded by review of full text.

3.3. Inclusion End Exclusion Criteria

Only original research articles were included. Inclusion criteria were: Qualitative research in EM/ED using observations, interviews and/or surveys with a qualitative component applying qualitative strategies of inquiry were included in the study. Selected were studies on practicing EM physicians working and training in the ED.

The exclusion criteria were: Qualitative interviews if solely used for purposes of quantification or tabulated counts of responses Studies involving solely students or other health care professionals than physicians (e.g., nurses, physiotherapists, paramedics) Papers that exclusively studied patients (patient perceptions, patient relatives, etc.) and papers on recruitment to EM and intern rotations Letters, case reports, commentaries, conference papers, descriptive papers and literature reviews, or reports on pre-hospital personnel.

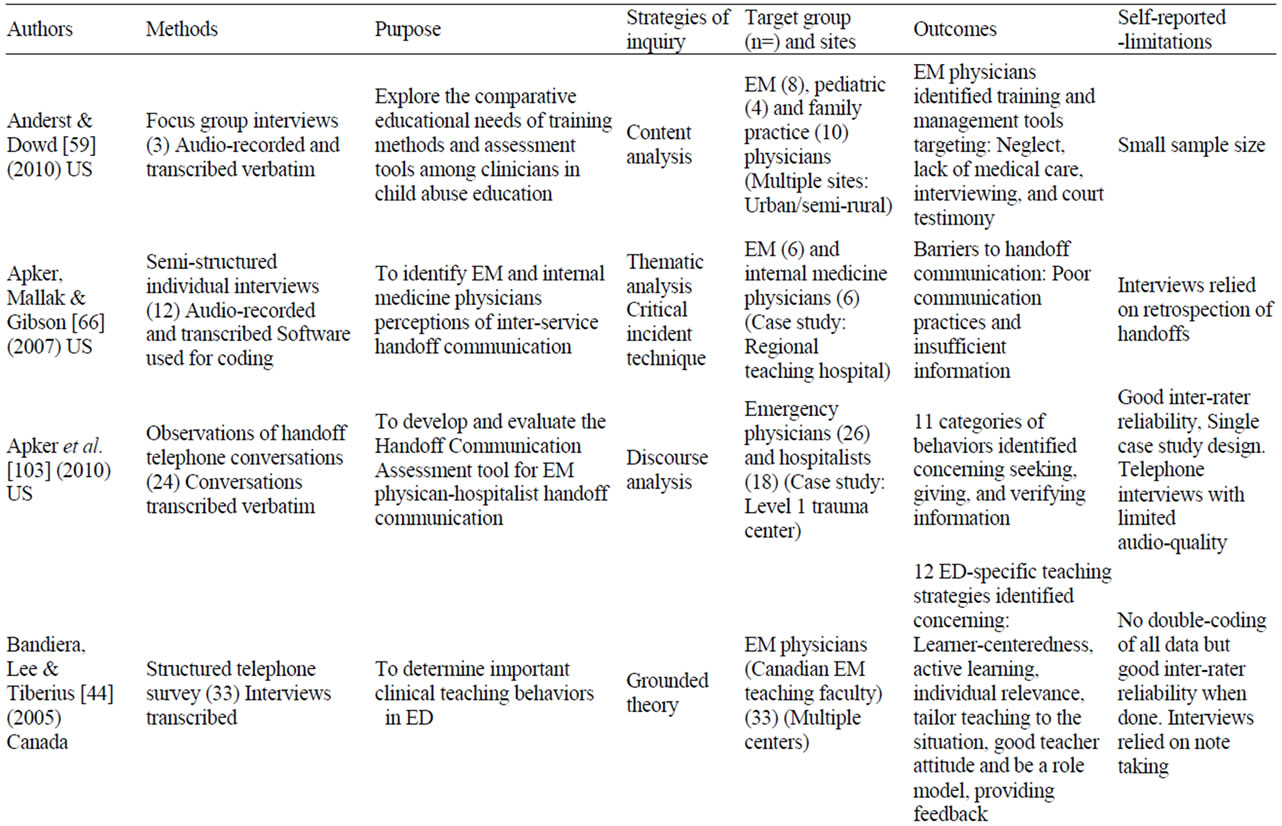

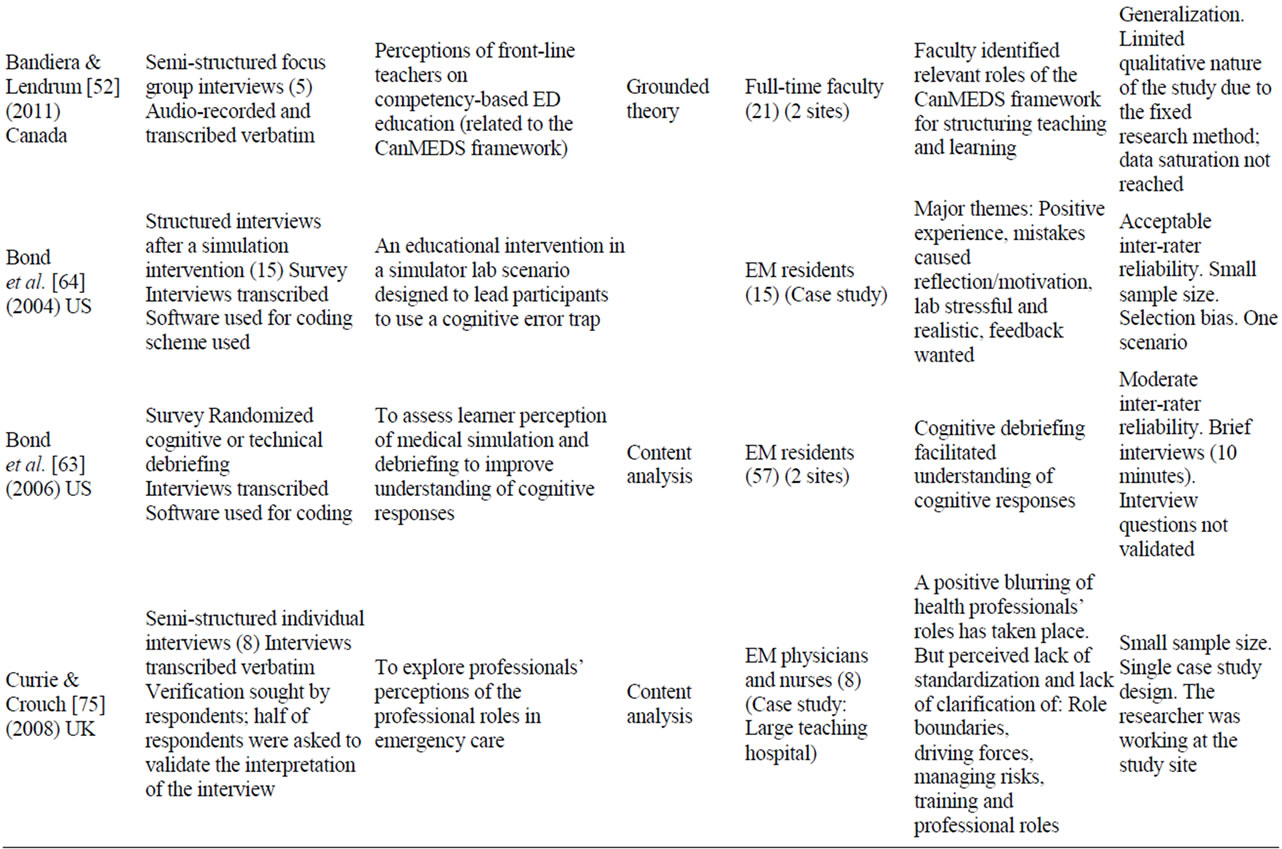

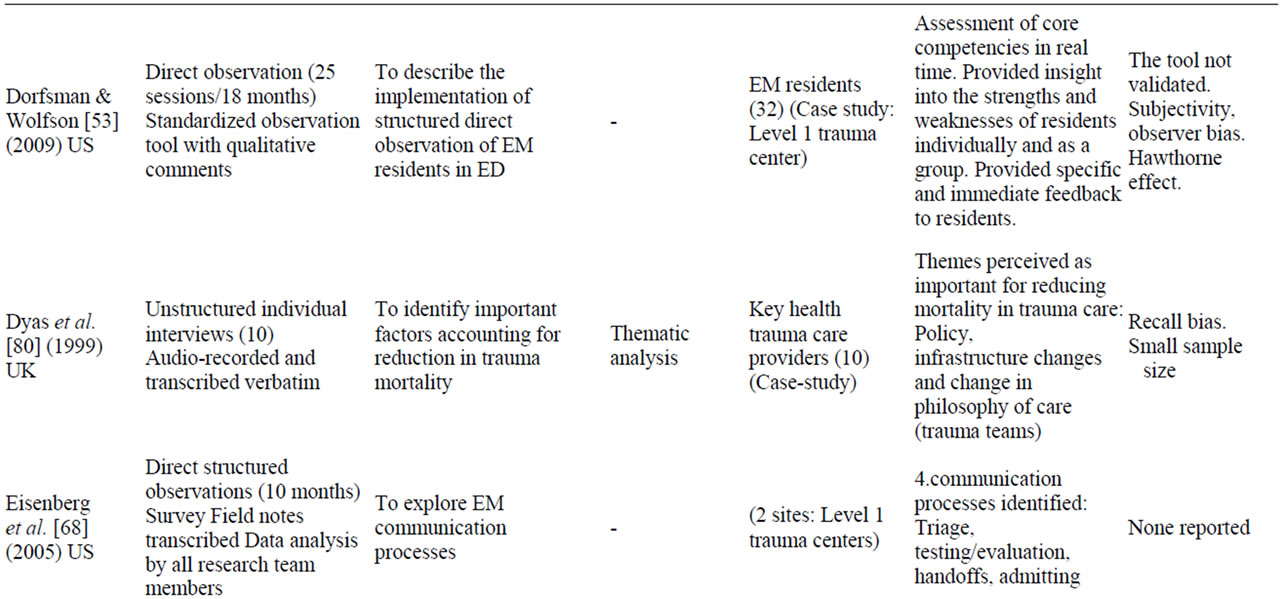

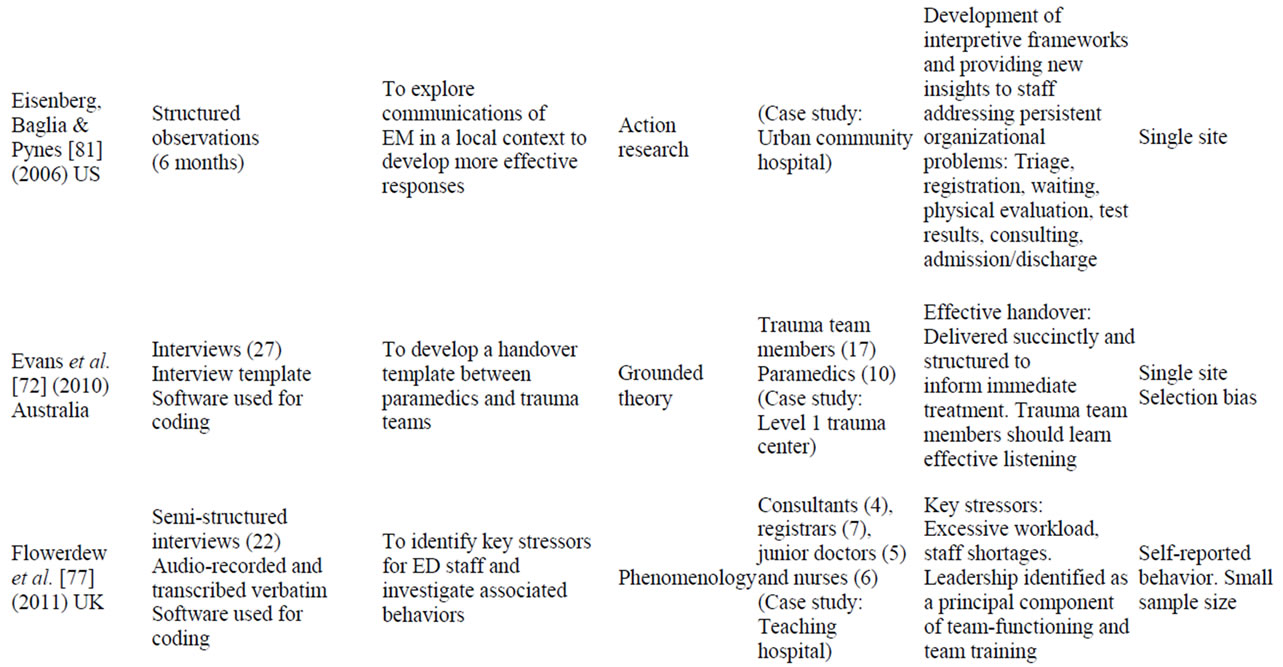

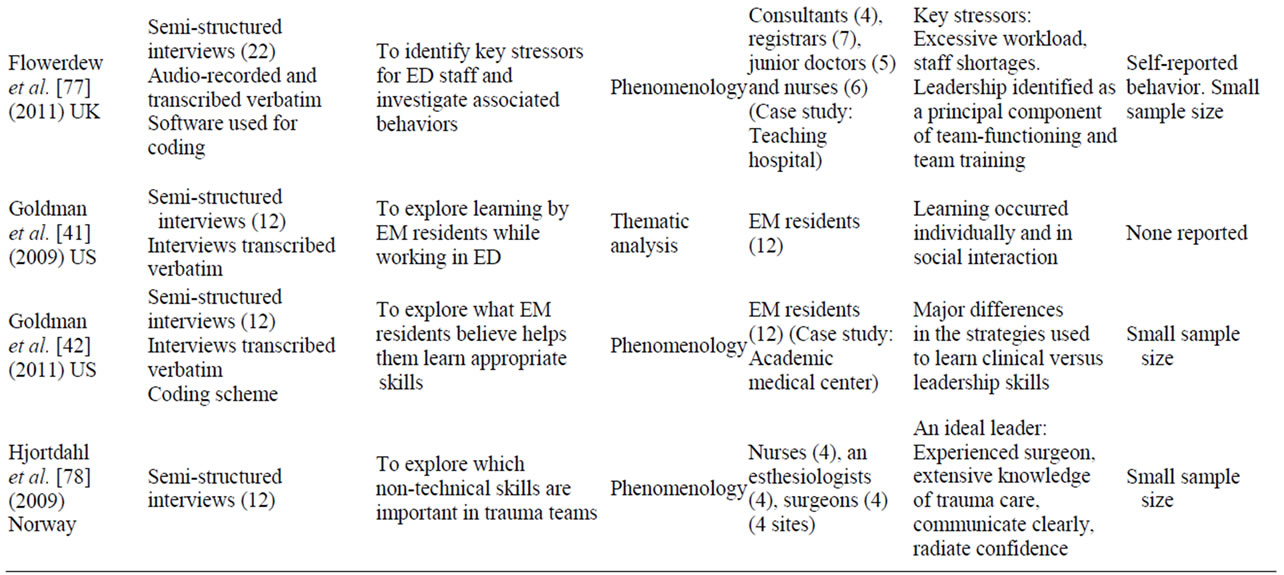

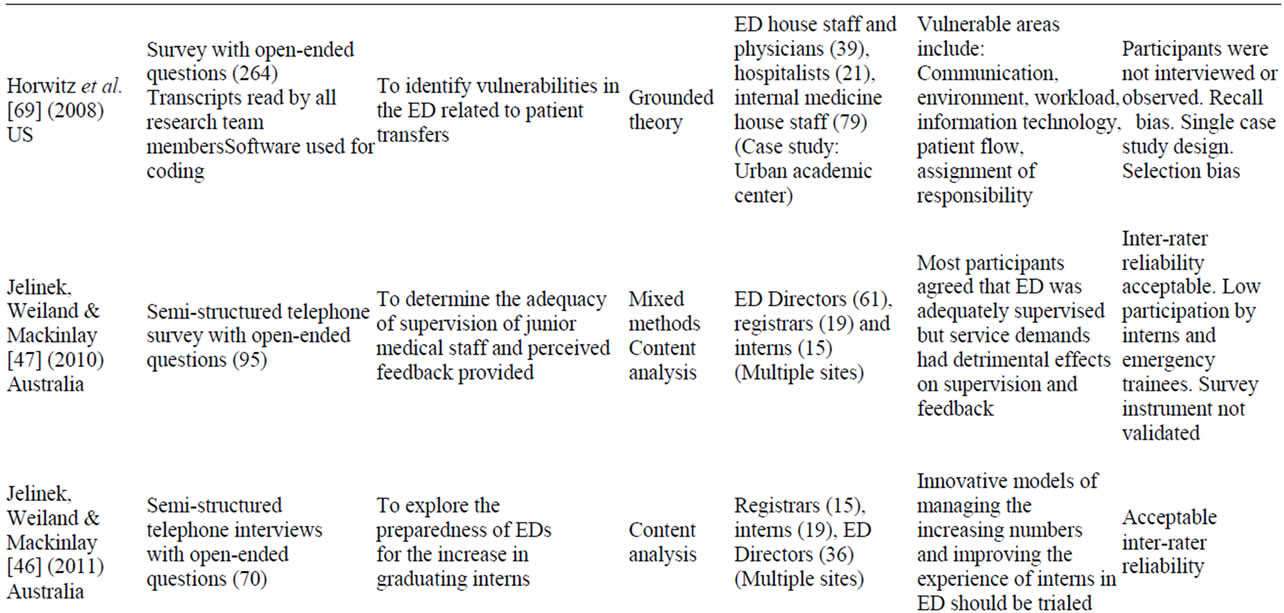

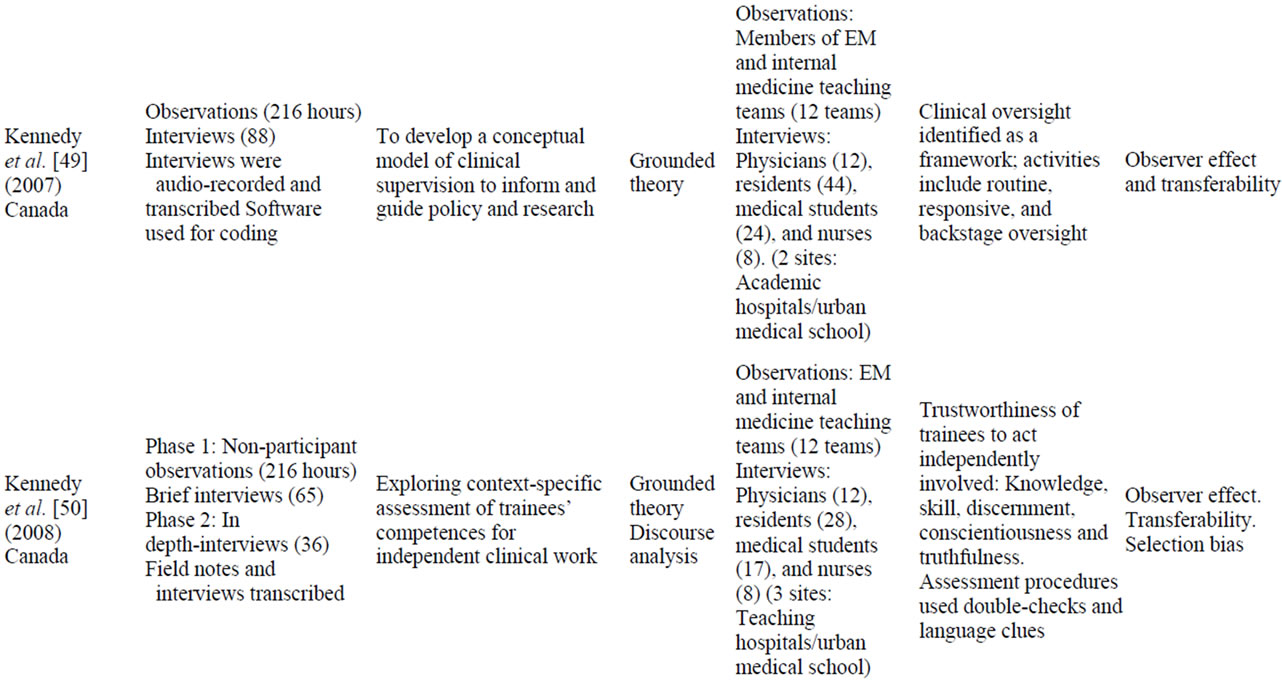

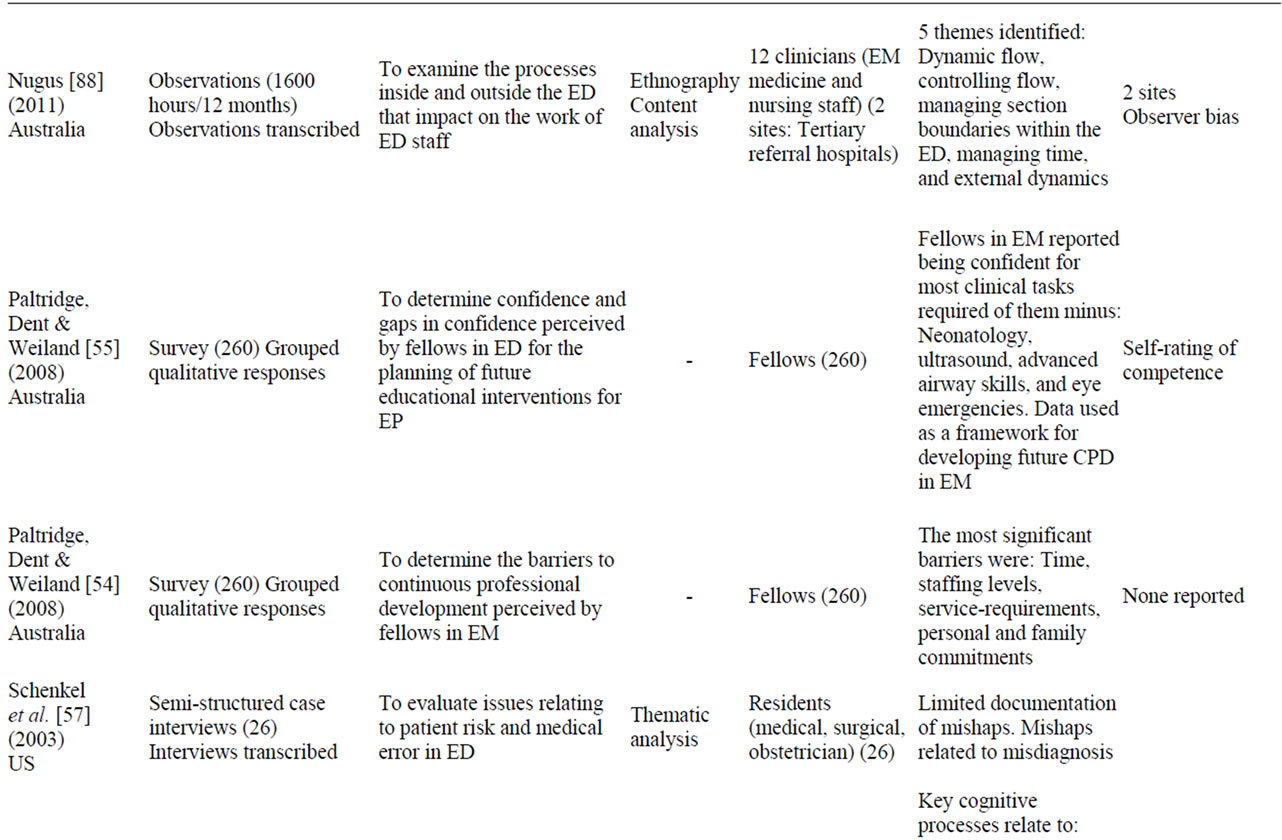

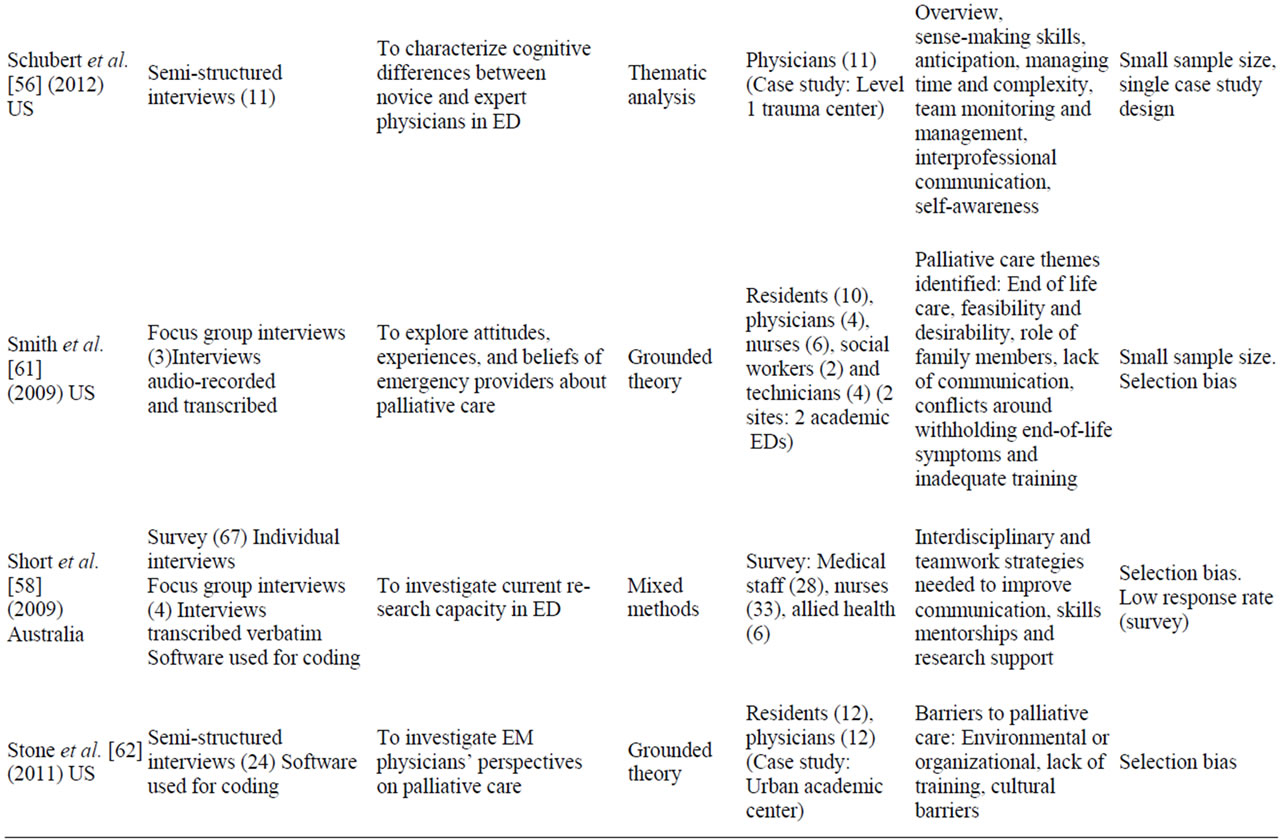

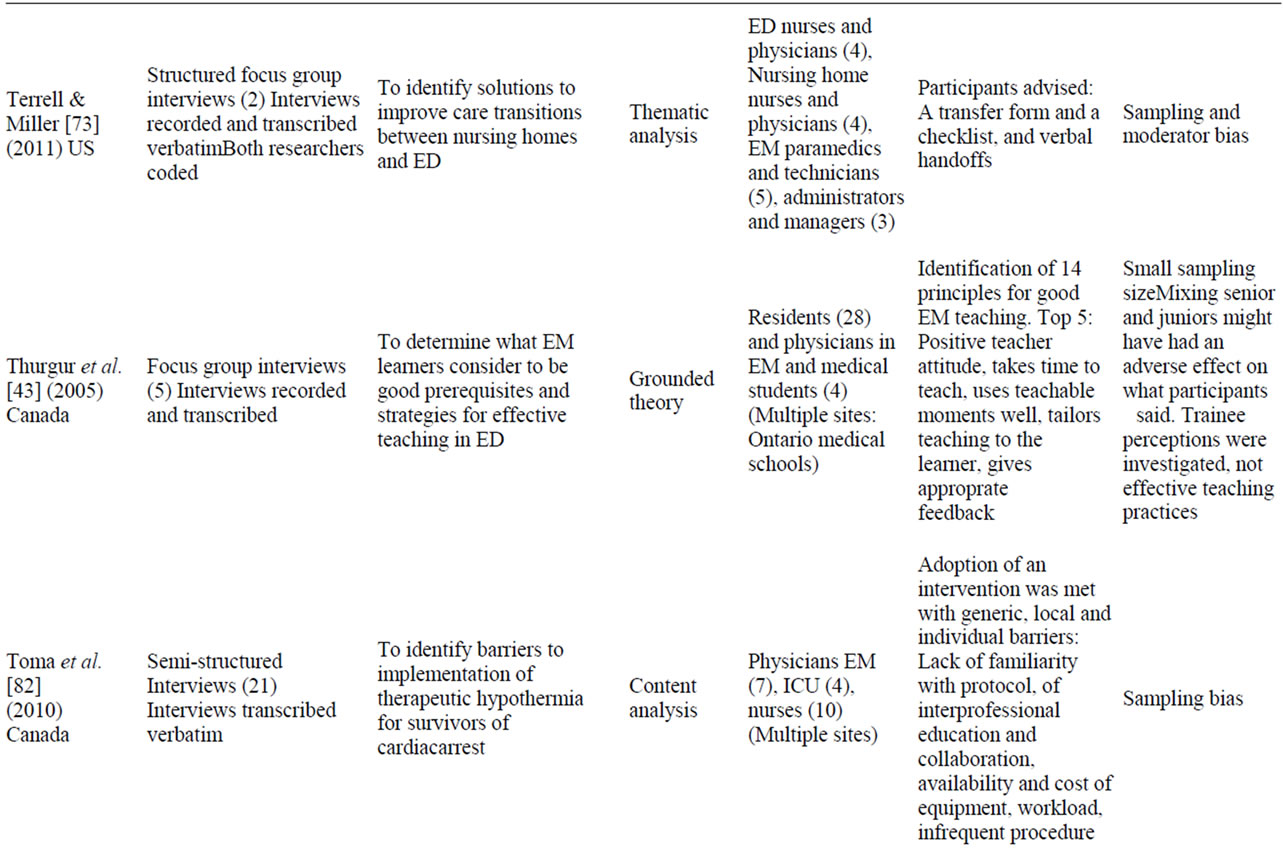

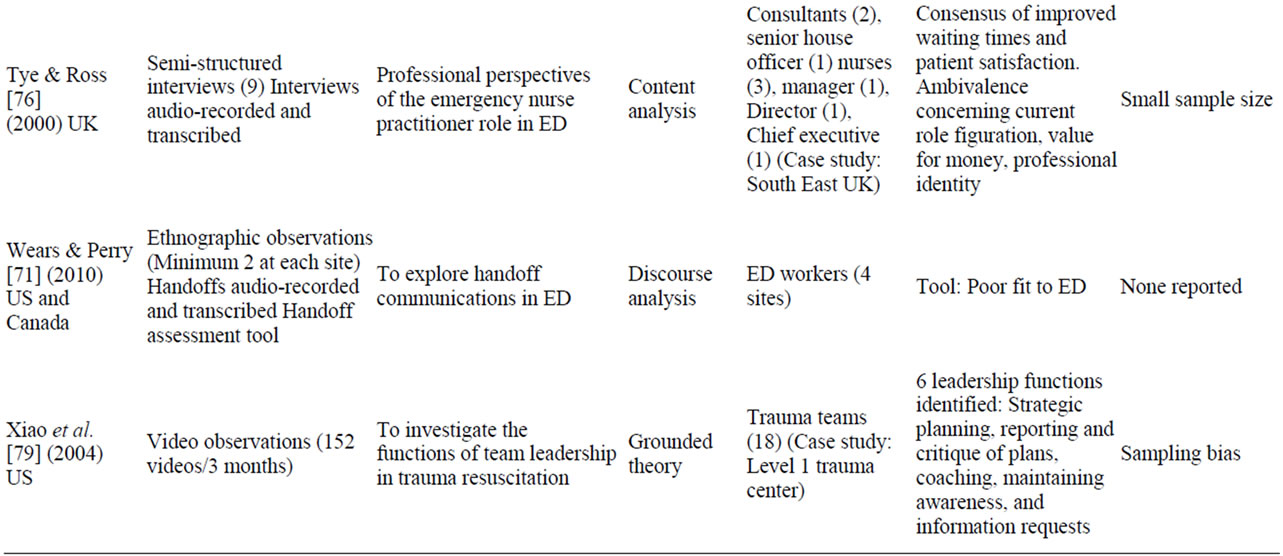

If there was reasonable doubt as to whether the study was in fact conducted within the EM or ED framework, for instance due to differences in international usage of the terms EM and ED The included studies are listed in Table 1.

4. Strategies of Inquiry in Qualitative Research

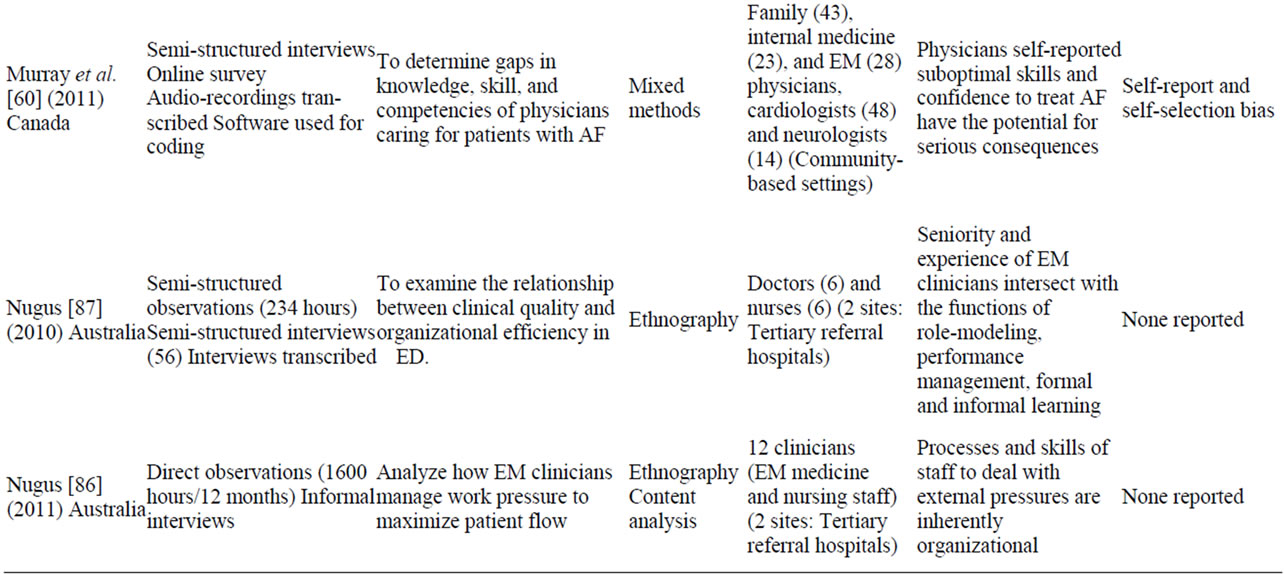

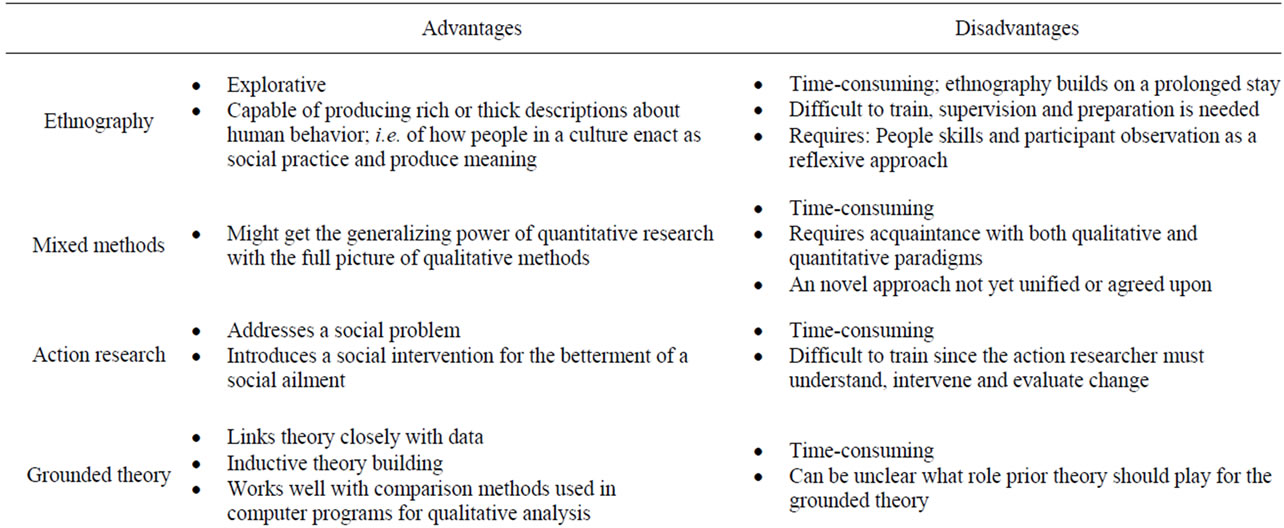

Before going into the results of this review, eight different strategies of inquiry pertaining to the qualitative research studies in this review will be briefly explained. The advantages and disadvantages of these qualitative strategies of inquiry are described in Table 2.

4.1. Ethnography

Ethnography grows out of the field work tradition of anthropology and sociology. Ethnography as qualitative strategy in medical research traditionally employs participant observation, open-ended interviewing and documentary analysis [15,16]. The hallmark of ethnography is participant observation where the researcher spends time in the field for prolonged periods of time [17]. Although field studies can be more time consuming than interviews, observational strategies are generally acknowledged valuable for gathering information about how people act rather than how they say they act. Ethnography is therefore an important approach to developing understanding about complex social interactions because it allows the researcher through participant observation to study medical work in situ [18].

Figure 1. Flowchart of search and selection strategy.

4.2. Mixed Methods

Mixed methods research combine elements from both qualitative and quantitative paradigms to produce converging findings in the context of complex research questions [19]. Mixed methods research integrates quantitative with qualitative research to answer how and why social phenomena are patterned the way they are [20]. The use of mixed methods in clinical medical studies is increasing, and aims to answer questions about both “how many” (prevalence, statistical significance, etc.) and “why” (sense-making) in the same study, and as such mixed methods are an important and useful approach to many questions in emergency care [21]. Central to a mixed methods study is a clear and strategic relationship among the methods in order to ensure that the data converge or triangulate to produce deeper insight than what a single method could yield [22].

Table 1. Included studies.

4.3. Action Research

Action research aims at changing a social practice and not only describing it. The people studied by action re searchers are conceived of as participants and action research is concerned with these people or their practice not a study about their behavior. Action research aims at formulating theories and solutions that change people’s lives. It is putting theory to the use in the real world [23, 24]. Participation is fundamental in action research. Action researchers work explicitly with and for the participants, by changing processes and monitoring the effects of the changes, and reflecting on the process and implications for social theory and practice. Examples of

Table 2. Advantages and disadvantages of the qualitative strategies of inquiry.

action research could include creating an improved ED learning environment or creating effects where participants’ action and reflection enhance and develop into spirals of positive change [25].

4.4. Grounded Theory

Grounded theory was developed by sociologists Glaser and Strauss [26] and further developed by Charmaz who described grounded theory as a set of methods that “consist of systematic, yet flexible guidelines for collecting and analyzing qualitative data to construct theories “grounded” in the data themselves” (p. 2) [27]. Grounded theory aims at developing theories or higher levels of understanding that are grounded in data; i.e. derived from a systematic analysis of data [22]. Grounded theory relies on an interpretive and iterative study design with theoretical sampling and constant comparisons of new and previously collected data [28,29]. A grounded theory study use these features to allow for the emergence of new conceptual models that extend beyond conventional thinking [30].

4.5. Phenomenology

Phenomenology as a qualitative research strategy is about the meaning of lived experience. This lived experience is traditionally studied through personal interviews with the subjects whose experience is in question. However, the experience of the researcher also becomes important. Phenomenological research pays attention to the structure of experience, what subjects reflect about their experiences and what the phenomenological analysis yields significant aspects of human experience [31]. In phenomenological research data analysis, recordings and transcriptions are approached with openness to whatever meanings emerge. This is an essential step in following the phenomenological reduction necessary to elicit the units of general meaning. The process of analysis proceeds by bracketing, the researcher’s preconceived meanings and interpretations without theoretical presuppositions [32]. This involves for the researcher to become aware of his or her own preconceptions about the phenomenon under study. The aim of analysis is to derive at the essence of a phenomena, for instance what is the essence of EM experiences empathy in the ED.

4.6. Content Analysis and thematic Analysis

Traditionally content analysis was used for quantitative purposes such as word frequencies. But when content analysis is used as a qualitative strategy of inquiry it refers to a form of thematic analysis. As a qualitative strategy of inquiry, content analysis is defined as “a research method for the subjective interpretation of the content of data through the systematic classification process of coding and identifying themes or patterns” [33]. In qualitative content analysis the researchers familiarize themselves with the data and search for underlying themes through coding that either arises from the research literature or from the data collected [34]. Qualitative content analysis has in recent years been developed into something called thematic analysis [35], which this study for the sake of brevity in this literature review will classify as content analysis. Thematic analysis and content analysis are both concerned with deriving at and analyzing themes defined as patterns of meaning.

4.7. Discourse Analysis

In discourse analysis the researcher investigates language-use as a social act. Discourse analysis aims to study how speech, text or some other talk is practiced and regulated as social phenomena [36]. The focus is often on naturally occurring talk since the object of analysis is how language is used within a social practice, for instance by health professionals in the ED/EM context. A researcher working within a discourse analytic tradition might ask: How is the EM field organized in terms of talk about what physicians do, why they do it, and what they hold as valuable? Data for discourse analysis might be text, gestures, words, but only to the extent that these cues offer evidence about how the social world is construed through discourse [37]. An important theme in discourse analysis is the intricate relationship between power and knowledge, in other words how discourse might be hegemonic.

4.8. The Critical Incident Technique

The critical incident technique was developed by Flanagan (1954) and provides a research-based approach for the investigation and analysis of clinical incidents to improve patient safety. In medical education, critical incident reports are being used to facilitate reflective learning [38]. This technique consists of a set of procedures for collecting direct observations of human behavior and observed incidents having special significance in such a way to facilitate their potential usefulness in solving practical problems [39]. The technique can proceed by interviewing experts through individual or group interviews about critical incidents, but questionnaires are also used. Also observations by trained observers observing how somebody perform the work under study, is a used strategy of data collection. As part of the critical incident technique, the collected data is analyzed through a process of categorization schemes or comprehensive summaries [40].

5. Results

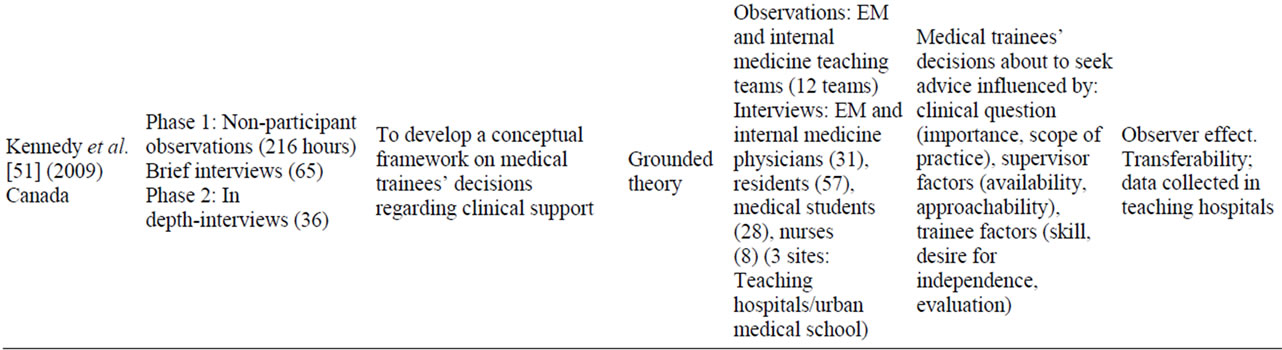

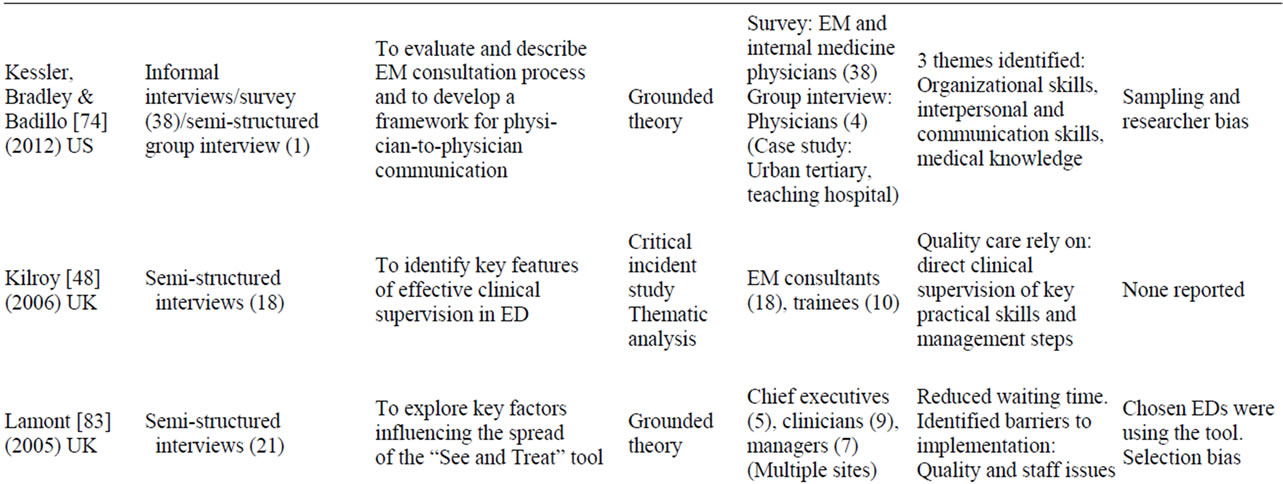

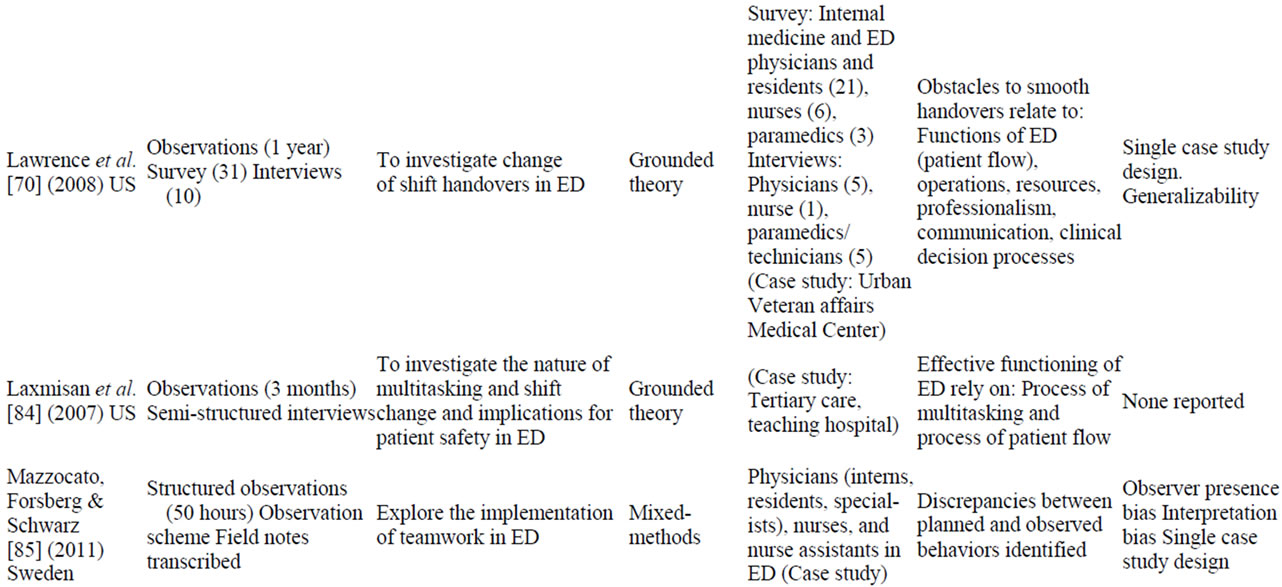

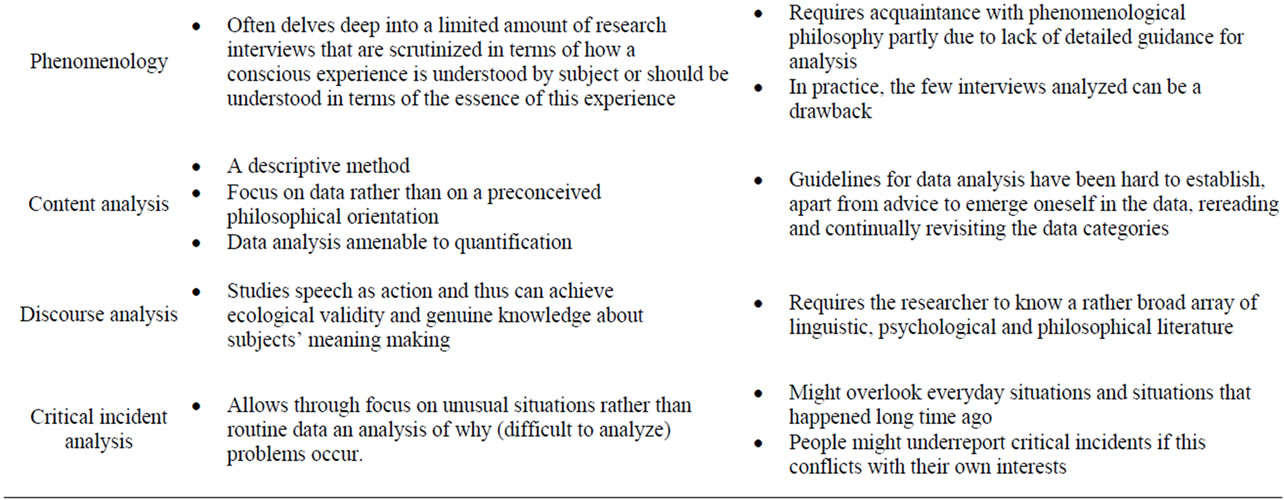

46 articles were included in this literature review and they are listed in Table 1. They were published between 1999 and 2011. This review found eight different quailtative strategies of inquiry in EM. The included studies were categorized into four themes and 12 sub-themes presented in Table 3. These themes were derived inductively; i.e. obtained gradually from the data. The four themes are: Education and training, communication, professsional roles, and organizational factors. All studies were classified, yet with several studies overlapping themes and sub-themes.

5.1. Theme 1: Education and training

Teaching Strategies

Studies used a number of contemporary learning theories including situated learning theory and chaos theory to understand EM physicians’ workplace learning [41,42]. In a phenomenological study, the Goldman group found major differences in residents’ learning strategies used to learn clinical skills versus learning leadership skills. They found, that clinical skill learning was approached with rigour and involved physicians, while leadership skill learning was unplanned and largely relied on nursing staff [42]. Thurgur found that EM medical staff had consistent views about good EM teaching strategies [43]. In a survey study, twelve specific teaching strategies for ED teaching were identified, for instance to actively involve the learner, the importance of the learning situation etc. [44] These findings are aligned with literature on medical education [45] and therefore one could argue they are not specific to ED teaching.

Supervision and feedback were pointed to as important to the education of ED junior staff [46-48]. Jelinek et al. call for a specific ED clinical intern supervisor [47]. In a series of grounded theory studies, Kennedy, Lingard and co-researchers explored the interrelationship between supervision, requests for clinical support and patient safety [49-51]. They found that, besides a simple clinical skill

Table 3. Themes and sub-themes.

assessment, supervising physicians also assessed the trust worthiness of trainees to act independently. Trust-worthiness involved knowledge and skill, discernment, conscientiousness, and truthfulness [50]. Trainees’ decisions about whether or not to seek clinical support were found to be a multifaceted and uncertain process influencing patient safety [51]. Some studies investigated competency based assessment [52,53] and areas where the resident training program can be improved. Two studies investigated EM physicians’ educational needs and barriers to continuing medical education in ED [54,55].

Several studies carried out educational needs assessments. Effective teaching and training methods should be targeting cognitive skills and differences in expertise in junior EM staff [56]. Medical error in the ED was studied from residents’ perspectives in terms of medical mishaps such as misdiagnosis [57]. Residents held the ED environment and the need for more knowledge and training responsible for medical errors. Another topic in ED was the need to develop staff’s research skills [55,58]. Some studies only had emergency medicine physicians as a peripheral research focus. These studies focused instead on educational needs assessments related to specific medical topics such as management of child abuse [59], atrial fibrillation [60], and palliative care [61,62].

Two studies investigated simulation practice and debriefing strategies in EM and highlighted the importance of reflection on mistakes and the need for cognitive feedback to ensure sound decision making [63,64].

5.2. Theme 2: Communication

The reviewed studies, in accordance with the patient safety literature [65], single out handoff communication as an important field of investigation [66-71]. These studies point especially to problems pertaining to insufficient information [66,67] and to a lack of assignment of responsibility [69] . One study developed a template for studying clinical handover in trauma teams [72]. Another related problem to handoffs was interdepartmental transfer oftenresulting in communication breakdowns [73]. These communication errors were caused by conflicting expectations between hospitalists and EM physicians concerning patient diagnosis [66]. The quality of physicianto-physician-consultation in ED was found to depend on interpersonal, clinical, communicational and organizationnal skills [74]. Eisenberg et al. [68] explored the relationship between EM communication and patient safety. They identified four routine communication processes crucial in determining both the direction and quality of care, and the risk of adverse events. A communication perspective of work in the ED depicts a combination of technical and narrative rationality that is not limited to a field dominated by logic and objectivity.

5.3. Theme 3: Professional Roles

Interestingly, one study identified blurring of roles as positive for collaboration [75] where as another study identified blurring role boundaries problematic and related to professional identity [76]. The relationship between team roles and stress was investigated [77]. Health professionals considered leadership and attitudes as important subthemes for functioning teams. In the trauma team, Hjortdahl [78] found that the trauma team leader should be an experienced surgeon who exhibits confidence. Via video analysis of trauma teams, Xiao [79] developed a catalogue of six leadership functions.

5.4. Theme 4: Work Organizational Factors

One study investigated organizational change and identified a mixture of national and regional policy factors as influencing trauma care [80]. An action research study aimed through studying the organizing practices in ED to change these practices to develop more efficient responses [81]. Individual and local barriers to implementtation of a therapeutic intervention were identified (hypothermia for resuscitated cardiac arrest) [82].

Work and patient flow: Some studies aimed to reduce waiting time [83]. Handover strategies were linked to the functions of the ED and this organizational context such as resources, patient flow, operations, professionalism, clinical decision processes and communication [70]. Some studies investigated workflow, team organization, and the multitasking of ED clinicians as important for patient safety [84,85]. In a series of studies, Nugus and colleagues [86-88] explored the interdependence of work flow and work pressure, the dichotomy of quality and effectiveness of patient care, and the inter-departmental context of ED. They found teamwork essential to patient flow. It was emphasized that ED staff strive for quality over efficiency in practice; i.e. pointing to the fact that staff was concerned with quality and work flow, namely how patient trajectories are made up by messy or complex networks of boundary work and the necessity for integrated care [87].

6. Discussion

6.1. Different Approaches

Qualitative research refers to a plethora of distinct strategies of inquiry, methods and philosophical approaches. But all qualitative studies should include clear descriptions of how they were conducted, including the selection of the study sample, the data collection methods, and the analysis process [9]. The point is that qualitative research can be assessed in terms of the degree to which it generates theory, is empirically grounded, scientifically credible, transferable to other settings, and internally reflexive with regard to the roles played by the researcher and participants [89,90]. Qualitative research might be undertaken to test a theory (deductive research) or to develop a theory (inductive). Clearly qualitative research can be explorative but good qualitative research still needs a research question either inductively or deductively. Qualitative research often emphasizes an inductive-subjective-contextual approach rather than a deductive-objective-generalizing approach [22].

6.2. Evaluation of the Quality of Qualitative Studies

Methods for literature reviews are well developed for trials, but not for qualitative research [91,92]. Systematic reviews apply explicit methods to this task, such as comprehensive literature searching and the quality assessment of studies.

In this review, the variation and inconsistencies in methods, terminology and selection of participants presented a number of challenges when the authors tried to apply any systematic analysis of the quality of the included papers. In the absence of consensus about standards for the evaluation of qualitative research, there is a danger that qualitative research results are misunderstood and judged inferior by those whose field of vision is firmly fixed on a hierarchy of evidence that makes randomized control trials the gold standard. But the fact that qualitative research is not a single unified approach to inquiry does not imply that it is a collection of unrelated practices, or that there are no relationships to practices of quantitative research. As this review shows, qualitative research relies on different traditions some of which are relatively well-confined and certainly well-defined in the literature [93].

Evaluation of qualitative research implies assessing the knowledge claims and the communication and contextualization of research findings [94]. Analyzing quailtative data is not a simple or quick process. Done properly, it is systematic, rigorous, labourand timeconsuming [95]. To establish rigour, i.e. validity and reliability [96] and to consider transferability, it is important for the reader to know which kinds of observations were carried out (direct, video, or participant observation), which interview techniques were used, for how long and by whom? The inductive nature of qualitative research requires sampling to the point of saturation, i.e. the researcher continues to recruit participants until no new data emerge [8]. Although the idea of saturation is helpful at the conceptual level, it provides little practical guidance for estimating sampling size, prior to data collection, necessary for conducting quality research. Much has been written about handling heterogeneity in quantitative systematic reviews but perhaps the importance of addressing heterogeneity in qualitative reviews in EM has been underestimated [97].

Several studies in this review discussed the selection of the emergency setting and the health professionals in terms of information bias or sampling bias [59,66,72, 74,98]. But in qualitative research, it is important to recognize that observer bias cannot be completely avoided. In phenomenology for instance, this problem is tackled through bracketing. But the point is that in all qualitative research, data is generated by people and people are part of power-discourses [36,50], e.g. action researchers [81] perform their research in close collaboration with participants, ethnography relies on researchers participating with people. In other words, observer bias is not a problem in qualitative research but a strategy.

A key question in qualitative research is: How the research moves from a description of data, through quotations or examples, to an analysis and interpretation of the meaning and significance of it? Though a journal article is commonly subjected to tight word limits, the reader should be able to decipher the views and analysis undertaken by the researcher from the description of the setting, and the interactions and accounts given by those who have been studied. In this review study, inter-observer reliability were discussed [44,46,63,67], i.e. the point that more than one researcher coded and read transcripts.

How does qualitative research contribute to a richer conceptualization of EM? Nugus and Braithwaite [87] showed that physicians negotiate quality and efficiency and thus showed how they make accountability a part of their day-to-day work.

“The study was a live window into the culture being socially produced through the behaviors of participants endeavoring to reconcile quality of care with efficient practice in a microcosm of the health system. The study showed that the mutual enactment of efficiency and quality generates and is generated by shared cultural definitions of the situation and guides the way care is organized and delivered by senior and junior staff” (p. 516) [87].

Thus by studying a situated practice a good ethnographic study might be able to provide an important glimpse into why and how people enact EM practices. As Nugus and Forero[88] argue, often research has already shown that something is the case (hand-off communication leads to medical errors, interdepartmental communication is difficult, other departments influence ED practice, etc.) but good qualitative research can provide an answer as to why this is the case. Other strength of qualitative research is its ability to grasp and operationalize complex relations. For instance, Kennedy and Lingaard and colleagues demonstrate the intricate relations between supervision and clinical support [49-51]. In studying competence assessment and its tacit dimensions the researchers are able to not only describe supervision but develop a clinical oversight typology.

While some studies employed long-time ethnography [53,68,70,79,81,86,88], e.g., more than fifty interviews before data saturation [49-51,87], and moved iteratively between theory construction and data analysis, other studies were not as thorough. Qualitative research is not a simple add-on to an evaluation study. While it is not difficult to conduct an interview or observe EM physicians, it takes research training and great acquaintance with the rather substantive qualitative research literature to make quality research. The distinctive contribution made by qualitative research in EM with regard to well conducted research, rigorous study design, the iterative research process and its management of data, systematic analysis and findings needs further attention. The importance of using qualitative research in EM can hardly be exaggerated. Use of qualitative research might contribute to a reconceptualization of emergency medicine practice.

Strengths and limitations of the review Qualitative studies can be difficult to search for and identify due to current methods for indexing qualitative research in bibliographic databases [99]. It is possible that the inclusion criteria may have been too narrow leading to under inclusion of other studies that are potentially relevant to EM and ED. The exclusion of studies involving solely non-physician providers may also contribute to under inclusion. But the goal of this review was to focus attention on qualitative research related to practicing EM physicians in the ED. However, the explicit search strategy in two databases, clear inclusion criteria, and systematic process used to identify and evaluate articles strengthen the quality of this literature review [100]. Nevertheless, the large volume of false hits, indicate that the fit between the search criteria and the relevant literature was less than perfect. Finally, all the reviewed studies were in English and this probably reflects a selection bias.

6.3. Future Studies

Although field observation, interviews and other qualitative methods can provide a range of interesting and insightful information concerning the organization of health care, it is widely recognized that medical practice is systematically accomplished through interactions of different health practitioners. These interactions are multimodal in that they rely upon the interplay of talk and coordination, as well as visual and material conduct. Future studies might use video, accompanied by a relevant methodological framework to provide the resources enabling us to begin to explicate and inform the practicalities of medical work in EM [101,102]. Mixed methods, in particular video observational studies might fill a gap in terms of understanding the meaning of specific communication interactions and link team performance to patient outcome.

REFERENCES

- S. Schenkel, “Promoting Patient Safety and Preventing Medical Error in Emergency Departments,” Academic Emergency Medicine, Vol. 7, No. 11, 2000, pp. 1204-1222. doi:10.1111/j.1553-2712.2000.tb00466.x

- D. Piquette, S. Reeves and V. R. Leblanc, “Interprofessional Intensive Care Unit Team Interactions and Medical Crises: A Qualitative Study,” Journal of Interprofessional Care, Vol. 23, No. 3, 2009, pp. 273-285. doi:10.1080/13561820802697818

- K. Carroll, R. Iedema and R. Kerridge, “Reshaping ICU Ward Round Practices Using Video-Reflexive Ethnography,” Qualitative Health Research, Vol. 18, No. 3, 2008, pp. 380-390. doi:10.1177/1049732307313430

- J. O. Jansen and B. H. Cuthbertson, “Detecting Critical Illness Outside the ICU: The Role of Track and Trigger Systems,” Current Opinion in Critical Care, Vol. 16, No. 3, 2010, pp. 184-190. doi:10.1097/MCC.0b013e328338844e

- G. J. Kuhn, P. Shayne, W. C. Coates, J. Fisher, M. Lin, L. A. Maggio, et al., “Critical Appraisal of Emergency Medicine Educational Research: The Best Publications of 2009,” Academic Emergency Medicine, Vol. 17, Suppl. 2, 2010, pp. S16-S25.

- P. Shayne, W. C. Coates, S. E. Farrell, G. J. Kuhn, M. Lin, L. A. Maggio, et al., “Critical Appraisal of Emergency Medicine Educational Research: The Best Publications of 2010,” Academic Emergency Medicine, Vol. 18, No. 10, 2011, pp. 1081-1089. doi:10.1111/j.1553-2712.2011.01191.x

- L. S. Binder and D. M. Chapman, “Qualitative Research Methodologies in Emergency Medicine,” Academic Emergency Medicine, Vol. 2, No. 12, 1995, pp. 1098-1102. doi:10.1111/j.1553-2712.1995.tb03156.x

- S. Cooper and R. Endacott, “Generic Qualitative Research: A Design for Qualitative Research in Emergency Care?” Emergency Medicine Journal, Vol. 24, No. 12, 2007, pp. 816-819. doi:10.1136/emj.2007.050641

- A. Kuper, L. Lingard and W. Levinson, “Critically Appraising Qualitative Research,” BMJ, Vol. 337, 2008, p. a1035. doi:10.1136/bmj.a1035

- N. Britten, “Qualitative Research on Health Communicationication: What Can It Contribute?” Patient Education and Counseling, Vol. 82, No. 3, 2011, pp. 384-388. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2010.12.021

- S. B. Issenberg, W. C. McGaghie, E. R. Petrusa, G. D. Lee and R. J. Scalese, “Features and Uses of High-Fidelity Medical Simulations That Lead to Effective Learning: A BEME Systematic Review,” Medical Teacher, Vol. 27, No. 1, 2005, pp. 10-28. doi:10.1080/01421590500046924

- S. B. Ssenberg, C. Ringsted, D. Ostergaard and P. Dieckmann, “Setting a Research Agenda for Simulation-Based Healthcare Education: A Synthesis of the Outcome from an Utstein Style Meeting,” Simulation in Healthcare, Vol. 6, No. 3, 2011, pp. 155-167. doi:10.1097/SIH.0b013e3182207c24

- T. Greenhalgh, “Papers That Summarise Other Papers, (Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses),” BMJ, Vol. 315, No. 7109, 1997, pp. 672-675. doi:10.1136/bmj.315.7109.672

- P. J. Zed, B. H. Rowe, P. S. Loewen and R. B. Abu-Laban, “Systematic Reviews in Emergency Medicine: Part I. Background and General Principles for Locating and Critically Appraising Reviews,” Canadian Journal of Emergency Medicine, Vol. 5, No. 5, 2003, pp. 331-335.

- P. Atkinson and L. Pugley, “Making Sense of Ethnography and Medical Education,” Medical Education, Vol. 39, No. 2, 2005, pp. 228-234. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2929.2004.02070.x

- J. P. Spradley, “The Ethnographic Interview,” Wadsworth, 1979.

- E. Murphy and R. Dingwall, “Qualitative Methods in Health Services Research,” In: N. Blach, Ed., Health Services Research Methods: A Guide to Best Practice, MJ Publishing, 1998.

- J. P. Spradley, “Participant Observation,” Wadsworth, 1980.

- J. W. Cresswell and V. L. Plano Clark, “Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research,” 2nd Edition, Sage, 2011.

- D. L. Morgan, “Paradigms Lost and Paradigms Regained: Methodological Implications of Combining Qualitative and Quantitative Methods,” Journal of Mixed Methods Research, Vol. 1, No. 1, 2007, pp. 48-76. doi:10.1177/2345678906292462

- S. Cooper, J. Porter and R. Endacott, “Mixed Methods Research: A Design for Emergency Care Research?” Emergency Medicine Journal, Vol. 28, No. 8, 2011, pp. 682-685. doi:10.1136/emj.2010.096321

- L. Lingard, M. Albert and W. Levinson, “Grounded Theory, Mixed Methods, and Action Research,” BMJ, Vol. 337, 2008, p. a567. doi:10.1136/bmj.39602.690162.47

- L. Forsythe, “Action Research, Simulation, Team Communication, and Bringing the Tacit into Voice Society for Simulation in Healthcare,” Simulation in Healthcare, Vol. 4, No. 3, 2009, pp. 143-148. doi:10.1097/SIH.0b013e3181986814

- R. Endacott, S. Cooper, R. Sheaff, J. Padmore and G. Blakely, “Improving Emergency Care Pathways: An Action Research Approach,” Emergency Medicine Journal, Vol. 28, No. 3, 2011, pp. 203-207. doi:10.1136/emj.2009.082859

- J. Meyer, “Using Qualitative Methods in Health Related Action Research,” BMJ, Vol. 320, 2000, pp. 178-181. doi:10.1136/bmj.320.7228.178

- B. G. Glaser and A. L. Strauss, “The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research,” Aldine, Chicago, 1967.

- K. Charmaz, “Constructing Grounded Theory. A Practical Guide through Qualitative Analysis,” SAGE Publications Ltd., 2006.

- M. Tavakol, S. Torabi and A. A. Zeinaloo, “Grounded Theory in Medical Education Research,” Medical Education Online, Vol. 11, No. 30, 2006, pp. 1-6.

- A. Bryant, “The SAGE Handbook of Grounded Theory,” 2010.

- T. J. Kennedy and L. A. Lingard, “Making Sense of Grounded Theory in Medical Education,” Medical Education, Vol. 40, No. 2, 2006, pp. 101-108. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2929.2005.02378.x

- M. Van Manen, “‘Doing’ Phenomenological Research and Writing: An Introduction,” No. 7, 1984, pp. 1-29.

- R. H. Hycner, “Some Guidelines for the Phenomenological Analysis of Interview Data,” Human Studies, Vol. 8, No. 3, 1985, pp. 279-303. doi:10.1007/BF00142995

- H. F. Hsieh and S. Shannon, “Three Approaches to Qualitative Content Analysis,” Qualitative Health Research, Vol. 15, No. 9, 2005, pp. 1277-1288. doi:10.1177/1049732305276687

- Y. Zhang and B. M. Wildemuth, “Qualitative Analysis of Content,” In: B. M. Wildemuth, Ed., Applications of Social Research Methods to Questions in Information and Library Science, Libraries Unlimited, 2009. pp. 1-12.

- V. Braun and V. Clarke, “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology,” Qualitative Research in Psychology, Vol. 3, No. 2, 2006, pp. 77-101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- J. P. Gee, “An Introduction to Discourse Analysis: Theory and Method,” Routledge, 2005.

- “The Discourse of Hospital Communication,” Palgrave Macmillan, 2007.

- W. T. Branch, “Use of Critical Incident Reports in Medical Education,” Journal of General Internal Medicine, Vol. 20, No. 11, 2005, pp. 1063-1067. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.00231.x

- J. C. Flanagan, “The Critical Incident Technique,” Psychological Bulletin, Vol. 51, No. 4, 1954, pp. 327-358. doi:10.1037/h0061470

- M. Woloshynowych, S. Rogers, S. Taylor-Adams and C. Vincent, “The Investigation and Analysis of Critical Incidents and Adverse Events in Healthcare,” Health Technology Assessment, Vol. 9, No. 19, 2005, pp. 1-158.

- E. Goldman, M. Plack, C. Roche, J. Smith and C. Turley, “Learning in a Chaotic Environment,” Journal of Workplace Learning, Vol. 21, No. 7, 2009, pp. 555-574. doi:10.1108/13665620910985540

- E. F. Goldman, M. M. Plack, C. N. Roche, J. P. Smith and C. L. Turley, “Learning Clinical versus Leadership Competencies in the Emergency Department: Strategies, Challenges, and Supports of Emergency Medicine Residents,” Journal of Graduate Medical Education, Vol. 3, No. 3, 2011, pp. 320-325.

- L. Thurgur, G. Bandiera, S. Lee and R. Tiberius, “What Do Emergency Medicine Learners Want from Their Teachers? A Multicenter Focus Group Analysis,” Academic Emergency Medicine, Vol. 12, No. 9, 2005, pp. 856-861. doi:10.1197/j.aem.2005.04.022

- G. Bandiera, S. Lee and R. Tiberius, “Creating Effective Learning in Today’s Emergency Departments: How Accomplished Teachers Get It Done,” Annals of Emergency Medicine, Vol. 45, No. 3, 2005, pp. 253-261. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2004.08.007

- D. M. Kaufman and K. V. Mann, “Teaching and Learning in Medical Education: How Theory Can Inform Practice,” In: T. Swanwick, Ed., Understanding Medical Education, Wiley-Blackwell, 2010, pp. 16-36.

- G. A. Jelinek, T. J. Weiland and C. Mackinlay, “Supervision and Feedback for Junior Medical Staff in Australian Emergency Departments: Findings from the Emergency Medicine Capacity Assessment Study,” BMC Medical Education, Vol. 10, 2010, p. 74. doi:10.1186/1472-6920-10-74

- G. A. Jelinek, T. Weiland and C. Mackinlay, “The Emergency Medicine Capacity Assessment Study: Perceived Resource Requirements to Support a Major Increase in Intern Numbers in Australian Emergency Departments,” Emergency Medicine Australasia, Vol. 23, No. 1, 2011, pp. 76-83. doi:10.1111/j.1742-6723.2010.01377.x

- D. A. Kilroy, “Clinical Supervision in the Emergency Department: A Critical Incident Study,” Emergency Medicine Journal, Vol. 23, No. 2, 2006, pp. 105-108. doi:10.1136/emj.2004.022913

- T. J. Kennedy, L. Lingard, G. R. Baker, L. Kitchen and G. Regehr, “Clinical Oversight: Conceptualizing the Relationship between Supervision and Safety,” Journal of General Internal Medicine, Vol. 22, No. 8, 2007, pp. 1080-1085. doi:10.1007/s11606-007-0179-3

- T. J. Kennedy, G. Regehr, G. R. Baker and L. Lingard, “Point-of-Care Assessment of Medical Trainee Competence for Independent Clinical Work,” Academic Medicine, Vol. 83, No. 10, 2008, pp. S89-S92. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e318183c8b7

- T. J. Kennedy, G. Regehr, G. R. Baker and L. Lingard, “Preserving Professional Credibility: Grounded Theory Study of Medical Trainees’ Requests for Clinical Support,” BMJ, Vol. 338, 2009, p. b128. doi:10.1136/bmj.b128

- G. Bandiera and D. Lendrum, “Dispatches from the Front: Emergency Medicine Teachers’ Perceptions of Competency-Based Education,” Canadian Journal of Emergency Medicine, Vol. 13, No. 3, 2011, pp. 155-161.

- M. L. Dorfsman and A. B. Wolfson, “Direct Observation of Residents in the Emergency Department: A Structured Educational Program,” Academic Emergency Medicine, Vol. 16, No. 4, 2009, pp. 343-351. doi:10.1111/j.1553-2712.2009.00362.x

- A. W. Dent, T. J. Weiland and D. Paltridge, “Australasian Emergency Physicians: A Learning and Educational Needs Analysis. Part five: Barriers to CPD Experienced by FACEM, and Attitudes to the ACEM MOPS Programme,” Emergency Medicine Australasia, Vol. 20, No. 4, 2008, pp. 339-346. doi:10.1111/j.1742-6723.2007.01042.x

- D. Paltridge, A. W. Dent and T. J. Weiland, “Australasian Emergency Physicians: A Learning and Educational Needs Analysis. Part two: Confidence of FACEM for Tasks and Skills,” Emergency Medicine Australasia, Vol. 20, No. 1, 2008, pp. 58-65. doi:10.1111/j.1742-6723.2007.01037.x

- C. C. Schubert, T. K. Denmark, B. Crandall, A. Grome and J. Pappas, “Characterizing Novice-Expert Differences in Macrocognition: An Exploratory Study of Cognitive Work in the Emergency Department,” Annals of Emergency Medicine, Vol. 61, No. 1, 2012, pp. 96-109.

- S. Schenkel, K. K. Rahul, M. M. Rosenthal, K. M. Sutcliffe and E. Lewton, “Resident Perceptions of Medical Errors in the Emergency Department,” Academic Emergency Medicine, Vol. 10, No. 12, 2003, pp. 1318-1324. doi:10.1111/j.1553-2712.2003.tb00004.x

- A. Short, A. Holdgate, N. Ahern and J. Morris, “Enhancing Research Interest and Collaboration in the Interdisciplinary Context of Emergency Care,” Journal of Interprofessional Care, Vol. 23, No. 2, 2009, pp. 156-168. doi:10.1080/13561820802675566

- J. Anderst and M. D. Dowd, “Comparative Needs in Child Abuse Education and Resources: Perceptions from Three Medical Specialties,” Medical Education Online, Vol. 15, 2010.

- S. Murray, P. Lazure and C. Pullen, P. Maltais and P. Dorian, “Atrial Fibrillation Care: Challenges in Clinical Practice and Educational Needs Assessment,” Canadian Journal of Cardiology, Vol. 27, No. 1, 2011, pp. 98-104. doi:10.1016/j.cjca.2010.12.006

- A. K. Smith, J. Fisher, M. A. Schonberg, D. J. Pallin, S. D. Block, L. Forrow, et al., “Am I Doing the Right Thing? Provider Perspectives on Improving Palliative Care in the Emergency Department,” Annals of Emergency Medicine, Vol. 54, No. 1, 2009, pp. 86-93. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2008.08.022

- S. C. Stone, S. Mohanty, C. R. Grudzen, J. Shoenberger, S. Asch, K. Kubricek, et al., “Emergency Medicine Physicians’ Perspectives of Providing Palliative Care in an Emergency Department,” Journal of Palliative Medicine, Vol. 14, No. 12, 2011, pp. 1333-1338. doi:10.1089/jpm.2011.0106

- W. F. Bond, L. M. Deitrick, M. Eberhardt, G. C. Barr, B. G. Kane, C. C. Worrilow, et al., “Cognitive versus Technical Debriefing after Simulation Training,” Academic Emergency Medicine, Vol. 13, No. 3, 2006, pp. 276-283. doi:10.1111/j.1553-2712.2006.tb01692.x

- W. F. Bond, L. M. Deitrick, D. C. Arnold, M. Kostenbader, G. C. Barr, S. R. Kimmel, et al., “Using Simulation to Instruct Emergency Medicine Residents in Cognitive Forcing Strategies,” Academic Medicine, Vol. 79, No. 5, 2004, pp. 438-446. doi:10.1097/00001888-200405000-00014

- L. A. Riesenberg, J. Leitzsch, J. L. Massucci, J. Jaeger, J. C. Rosenfeld, C. Patow, et al., “Residents’ and Attending Physicians’ Handoffs: A Systematic Review of the Literature,” Academic Medicine, Vol. 84, No. 12, 2009, pp. 1775-1787. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181bf51a6

- J. Apker, L. A. Mallak and S. C. Gibson, “Communicating in the ‘Gray Zone’: Perceptions about Emergency Physician Hospitalist Handoffs and Patient Safety,” Academic Emergency Medicine, Vol. 14, No. 10, 2007, pp. 884-894.

- J. Apker, K. M. Propp and W. S. Ford, “Investigating the Effect of Nurse-Team Communication on Nurse Turnover: Relationships among Communication Processes, Identification, and Intent to Leave,” Health Communication, Vol. 24, No. 2, 2010, pp. 106-114. doi:10.1080/10410230802676508

- E. Eisenberg, A. G. Murphy, K. M. Sutcliffe, R. Wears, S. P. Schenkel and M. Vanderhoef, “Communication in Emergency Medicine: Implications for Patient Safety,” Communication Monographs, Vol. 72, No. 4, 2005, pp. 390-413. doi:10.1080/03637750500322602

- L. I. Horwitz, T. Meredith, J. D. Schuur, N. R. Shah, R. G. Kulkarni and G. Y. Jenq, “Dropping the Baton: A Qualitative Analysis of Failures during the Transition from Emergency Department to Inpatient Care,” Annals of Emergency Medicine, Vol. 53, No. 6, 2009, pp. 701-710. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2008.05.007

- R. H. Lawrence, A. M. Tomolo, A. P. Garlisi and D. C. Aron, “Conceptualizing Handover Strategies at Change of Shift in the Emergency Department: A Grounded Theory Study,” BMC Health Services Research, Vol. 8, 2008, p. 256. doi:10.1186/1472-6963-8-256

- R. L. Wears and S. J. Perry, “Discourse and Process Analyses of Shift Change Handoffs in Emergency Departments,” 2010, pp. 953-956.

- S. M. Evans, A. Murray, I. Patrick, M. Fitzgerald, S. Smith and P. Cameron, “Clinical Handover in the Trauma Setting: A Qualitative Study of Paramedics and Trauma Team Members,” BMJ Quality and Safety, Vol. 19, No. 6, 2010, p. e57. doi:10.1136/qshc.2009.039073

- K. M. Terrell and D. K. Miller, “Strategies to Improve Care Transitions between Nursing Home and Emergency Departments,” Journal of American Medical Directors Association, Vol. 12, No. 8, 2011, pp. 602-605. doi:10.1016/j.jamda.2010.09.007

- C. Kessler, B. M. Kutka and C. Badillo, “Consultation in the Emergency Department: A Qualitative Analysis and Review,” The Journal of Emergency Medicine, Vol. 42, No. 6, 2012, pp. 704-711. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2011.01.025

- J. Currie and R. Crouch, “How Far is Too Far? Exploring the Perceptions of the Professions on Their Current and Future Roles in Emergency Care,” Emergency Medicine Journal, Vol. 25, No. 6, 2008, pp. 335-339. doi:10.1136/emj.2007.047332

- C. C. Tye and F. M. Ross, “Blurring Boundaries: Professional Perspectives of the Emergency Nurse Practitioner Role in a Major Accident and Emergency Department,” Journal of Advanced Nursing, Vol. 31, No. 5, 2000, pp. 1089-1096. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2648.2000.01380.x

- L. Flowerdew, R. Brown, S. Russ, C. Vincent and M. Woloshynowych, “Teams under Pressure in the Emergency Department: An Interview Study,” Emergency Medicine Journal, Vol. 29, No. 12, 2012, p. e2.

- M. Hjortdahl, A. H. Ringen, A. C. Naess and T. Wisborg, “Leadership Is the Essential Non-Technical Skill in the Trauma Team—Results of a Qualitative Study,” Scandinavian Journal of Trauma, Resuscitation and Emergency Medicine, Vol. 17, 2009, p. 48. doi:10.1186/1757-7241-17-48

- Y. Xiao, F. J. Seagull, C. F. Mackenzie and K. Klein, “Adaptive Leadership in Trauma Resuscitation Teams: A Grounded Theory Approach to Video Analysis,” Cognition, Technology & Work, Vol. 6, No. 3, 2004, pp. 154-164. doi:10.1007/s10111-004-0157-z

- J. Dyas, P. Ayres, M. Airey and J. Connelly, “Management of Major Trauma: Changes Required for Improvement,” Quality in Health Care, Vol. 8, No. 2, 1999, pp. 78-85. doi:10.1136/qshc.8.2.78

- E. M. Eisenberg, J. Baglia and J. E. Pynes, “Transforming Emergency Medicine through Narrative: Qualitative Action Research at a Community Hospital,” Health Communication, Vol. 19, No. 3, 2006, pp. 197-208. doi:10.1207/s15327027hc1903_2

- A. Toma, C. M. Bensimon, K. N. Dainty, G. D. Rubenfeld, L. J. Morrison and S. C. Brooks, “Perceived Barriers to Therapeutic Hypothermia for Patients Resuscitated from Cardiac Arrest: A Qualitative Study of Emergency Department and Critical Care Workers,” Critical Care Medicine, Vol. 38, No. 2, 2010, pp. 504-509. doi:10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181cb0a02

- S. S. Lamont, “‘See and Treat’: Spreading Like Wildfire? A Qualitative Study into Factors Affecting Its Introduction and Spread,” Emergency Medicine Journal, Vol. 22, No. 8, 2005, pp. 548-552. doi:10.1136/emj.2004.016303

- A. Laxmisan, F. Hakimzada, O. R. Sayan, R. A. Green, J. Zhang and V. L. Patel, “The Multitasking Clinician: Decision-Making and Cognitive Demand during and after Team Handoffs in Emergency Care,” International Journal of Medical Informatics, Vol. 76, No. 11-12, 2007, pp. 801-811. doi:10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2006.09.019

- P. Mazzocato, H. H. Forsberg and U. T. Schwarz, “Team Behaviors in Emergency Care: A Qualitative Study Using Behavior Analysis of What Makes Team Work,” Scandinavian Journal of Trauma, Resuscitation and Emergency Medicine, Vol. 19, 2011, p. 70. doi:10.1186/1757-7241-19-70

- P. Nugus, A. Holdgate, M. Fry, R. Forero, S. McCarthy and J. Braithwaite, “Work Pressure and Patient Flow Management in the Emergency Department: Findings from an Ethnographic Study,” Academic Emergency Medicine, Vol. 18, No. 10, 2011, pp. 1045-1052. doi:10.1111/j.1553-2712.2011.01171.x

- P. Nugus and J. Braithwaite, “The Dynamic Interaction of Quality and Efficiency in the Emergency Department: Squaring the Circle?” Social Science & Medicine, Vol. 70, No. 4, 2010, pp. 511-517. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.11.001

- P. Nugus and R. Forero, “Understanding Interdepartmental and Organizational Work in the Emergency Department: An Ethnographic Approach,” International Emergency Nursing, Vol. 19, No. 2, 2011, pp. 69-74. doi:10.1016/j.ienj.2010.03.001

- M. Hammersley, “What’s Wrong with Ethnography? Methodological explorations,” Routledge, 1987.

- N. K. Denzin and Y. S. Lincoln, “Handbook of Qualitative Research,” 2nd Edition, Sage Publications, Inc., London, 2000.

- A. Harden, J. Garcia, S. Oliver, R. Rees, J. Shepherd, G. Brunton, et al., “Applying Systematic Review Methods to Studies of People’s Views: An Example from Public Health Research,” Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health, Vol. 58, No. 9, 2004, pp. 794-800. doi:10.1136/jech.2003.014829

- S. Goodacre, “Critical Appraisal for Emergency Medicine: 6 Systematic Reviews,” Emergency Medicine Journal, Vol. 26, No. 2, 2009, pp. 114-116. doi:10.1136/emj.2007.057356

- A. Kuper, S. Reeves and W. Levinson, “An Introduction to Reading and Appraising Qualitative Research,” BMJ, Vol. 337, 2008, p. a288. doi:10.1136/bmj.a288

- B. Stige, K. Malterud and T. Midtgarden, “Toward an Agenda for Evaluation of Qualitative Research,” Adv Qual Method, Vol. 19, No. 10, 2009, pp. 1504-1516.

- C. Pope, S. Ziebland and N. Mays, “Qualitative Research in Health Care. Analysing Qualitative Data,” BMJ, Vol. 320, No. 7227, 2000, pp. 114-116. doi:10.1136/bmj.320.7227.114

- S. Cooper, R. Endacott and Y. Chapman, “Qualitative Research: Specific Designs for Qualitative Research in Emergency Care?” Emergency Medicine Journal, Vol. 26, No. 11, 2009, pp. 773-776. doi:10.1136/emj.2008.071159

- P. J. Zed, B. H. Rowe, P. S. Loewen and R. B. Abu-Laban, “Systematic Reviews in Emergency Medicine: Part II. Critical Appraisal of Review Quality, Data Synthesis and Result Interpretation,” Canadian Journal of Emergency Medicine, Vol. 5, No. 6, 2003, pp. 406-411.

- C. Kessler and J. H. Burton, “Moving beyond Confidence and Competence: Educational Outcomes Research in Emergency Medicine,” Academic Emergency Medicine, Vol. 18, Suppl. 2, 2011, pp. S25-S26. doi:10.1111/j.1553-2712.2011.01169.x

- R. L. Shaw, A. Booth, A. J. Sutton, T. Miller, J. A. Smith, B. Young, et al., “Finding Qualitative Research: An Evaluation of Search Strategies,” BMC Medical Research Methodology, Vol. 4, 2006, p. 5. doi:10.1186/1471-2288-4-5

- J. Popay, A. Rogers and G. Williams, “Rationale and Standards for the Systematic Review of Qualitative Literature in Health Services Research,” Qualitative Health Research, Vol. 8, No. 3, 1998, pp. 341-351. doi:10.1177/104973239800800305

- C. Heath, P. Luff and M. S. Svensson, “Video and Qualitative Research: Analysing Medical Practice and Interaction,” Medical Education, Vol. 41, No. 1, 2007, pp. 109-116. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2929.2006.02641.x

- R. Iedema, D. Long, R. Forsyth and B. B. Lee, “Visibilising Clinical Work: Video Ethnography in the Contemporary Hospital,” Health Sociology Review, Vol. 15, No. 2, 2006, pp. 156-168. doi:10.5172/hesr.2006.15.2.156

- J. Apker, K. M. Propp and W. S. Ford, “Investigating the Effect of Nurse-Team Communication on Nurse Turnover: Relationships among Communication Processes, Identification, and Intent to Leave,” Health Communication, Vol. 24, No. 2, 2009, pp. 106-114. doi:10.1080/10410230802676508

- J. Fisher, M. J. Steggal and C. L. Cox, “Developing the A&E Nurse Practitioner Role,” Emergency Nursing, Vol. 13, No. 10, 2006, pp. 26-31.