International Journal of Clinical Medicine

Vol.2 No.2(2011), Article ID:5100,9 pages DOI:10.4236/ijcm.2011.22021

Application of “Swanson’s Middle Range Caring Theory” in Sweden after Miscarriage

—Swanson’s Middle Range Caring Theory, Miscarriage, Missed Miscarriage, Qualitative Method

![]()

1Division of Reproductive and Perinatal Health Care, Department of Women’s Health, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden; 2School of Life Sciences, University of Skövde, Skövde, Sweden.

Email: caroline.jansson@karolinska.se, annsofie.adolfsson@his.se

Received January 26th, 2011; revised April 5th, 2011; accepted April 20th, 2011.

Keywords: Swanson’s Middle Range Caring Theory, Miscarriage, Missed Miscarriage, Qualitative Method

ABSTRACT

Objective: The aim of this study was to apply Swanson’s Middle Range Caring Theory to the follow-up visit with a midwife for Swedish women who have suffered early miscarriage or received care for late missed miscarriage in pregnancy week 18 - 20. Methods: Twenty-five tape recorded interviews with women four weeks after their early miscarriages and thirteen tape recorded semi-structured interviews with midwives and nurses who had the experience of caring for women who have been diagnosed with a missed miscarriage during a routine ultrasound scan. The interviews were transcribed verbatim and interpreted deductively from the text using the theory. Results: Each woman described her personal experience of miscarriage in the relative terms of a human experience. The midwives and nurses described their experiences with women who received care for missed miscarriage. The interviews included information about the treatment provided by the caregivers during the period afterward of the diagnosis. The caregiver attitude was formed from Swanson’s caring categories: “Maintaining belief”, “knowing”, “being with”, “doing for”, “enabling”. Conclusions: Swanson’s Middle Range Caring Theory as applied to the caregiver includes being emotionally present, giving support with respect for the woman’s dignity, being competent, meeting each woman’s own individual needs. Given the proper care after a miscarriage every woman has the power within herself to improve their wellbeing.

1. Introduction

Approximately twenty percent of women who give birth in Sweden report earlier experience of miscarriage. This equates to approximately 20,000 miscarriages each year in Sweden [1]. Women who experience miscarriage have a deep sense of loss and they feel guilt and emptiness. Women experience this loss differently as individuals [2]. The choice of using different methods of coping with pregnancy loss depends on the individual women and their partner [3].

After a miscarriage some women may experience a state of shock and have a total grief reaction [2,4]. The acute crisis consists of the shock phase when it is difficult to remember what has happened and is followed by the reaction phase which is when the person begins to absorb the event and returns to a state of awareness. This initial phase is followed by a period of reflection and reorientation [5]. Most women who have experienced amissed miscarriage suffer from grief and some may need professional support [4].

In one study from Sweden it was demonstrated that women diagnosed with a missed miscarriage suffered more grief after four weeks than women who experienced other forms of miscarriage. Some of the women who suffered a missed miscarriage experienced an increase in their feelings of grief after four months instead of a decrease as would be expected [6]. The care given after the experience has a significant impact on the grief reaction after a miscarriage [4,7,8].

Descriptions of the sense of grief felt by women that typically follow a miscarriage tend to vary significantly and tend to match the descriptions of grief that accompany other forms of significant loss. Although additional research is clearly needed the guidelines for coping with grief following a miscarriage can be safely based on the data available for coping with other significant types of losses [9]. Most women have normal grief reactions after a miscarriage such as being distraught emotionally, feeling ill at ease and other accompanying health ailments. The different responses following a miscarriage can range from tears, and other expressions of anxiety [2,9].

Given the range of potential interpretations of the nature of this particular loss, the loss of a fetus as compared to a potential child and human being, practitioners and caregivers should encourage women to articulate and act out the specific nature of their loss to assist them in resolving the experience [9]. Previous research has found that follow up visits to a nurse after one week, after five weeks, and after eleven weeks of the diagnosis of miscarriage had the broadest overall positive impact on the couples’ resolution of grief reaction and depression [8]. Women and their partners who have suffered a missed miscarriage tend to need extended support on an individual basis in addition to the follow up assistance assessed by the midwives [4].

Swanson’s Middle Range Caring Theory is an effective and sensitive guide to clinical practice with women who have experienced a miscarriage [10]. The theory includes five categories of the therapeutic caring process which are maintaining belief, knowing, being with, doing for and enabling [11,12]. The categories have the following definition. “Maintaining belief” is defined as “Sustaining faith in the other’s capacity to get through an event or transition and face a future fulfillment”. Maintaining belief is the basis of practical healthcare. “Knowing” is defined as “Striving to understand an event as it has meaning in the life of the other”. “Being” it is defined as “Being emotionally present to other”. “Doing for” is defined as. “Doing for the other as he/she would do for the self if it was at all possible”. “Enabling” is defined as: “Facilitating the other’s passage through life transitions and unfamiliar events” [13]. The process emphasizes maintaining confidence in the ability of the woman to survive and get through the event and at the same time appreciating her difficulty in coping. A sound relationship between the midwife and the woman is important irrespective of how the situation develops in order to help the woman find meaning and relevance to the unfortunate event as a valuable learning experience in her life. The woman’s experience of wellbeing increases with the care given according to the theory [11,13-16]. Empirical studies were used to develop Swanson’s Middle Range Caring Theory. The theory are compared and contrasted with Cobb’s definition of social support [17] and Watson “carative” factors [18,19] and Benner’s description of the role of nursing [20]. The theory has been tested in practice during the caring process [14] and for its impact on women’s wellbeing [13]. The aim of this study was to apply Swanson’s Middle Range Caring Theory to the follow up visit with a midwife for Swedish women who have suffered early miscarriage or received care for late missed miscarriage in pregnancy week 18 - 20.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Design

A deductive study was performed with data accumulated from two different contexts interviews in Sweden. In 2002 - 2003 one of the interviews was conducted with the women who had experienced miscarriage [6] and in 2007 with the nurses and midwives who cared for the men and women who shared the experience as a couple of late missed miscarriage [4]. All interviews were transcribed and analyzed deductively according to Swanson’s Middle Range Caring Theory [14].

2.2. Statistics of Participants in Group One

The participants in this study were divided into two groups. Group one (women) included the women who had experienced a miscarriage and participated in the structured followed-up visit that included a tape recorded interview four weeks after early miscarriage. The study period was from August 2002 to June 2003. The inclusion criteria included only participants who had a miscarriage diagnosed before the thirteenth week in the pregnancy term by an ultrasound examination. Participants were also required to speak Swedish. Exclusion criteria included those women who kept their pregnancy secret to their spouses and next of kin and also those women who were younger than eighteen years of age. Of the potential eligible women twenty-five agreed to participate.

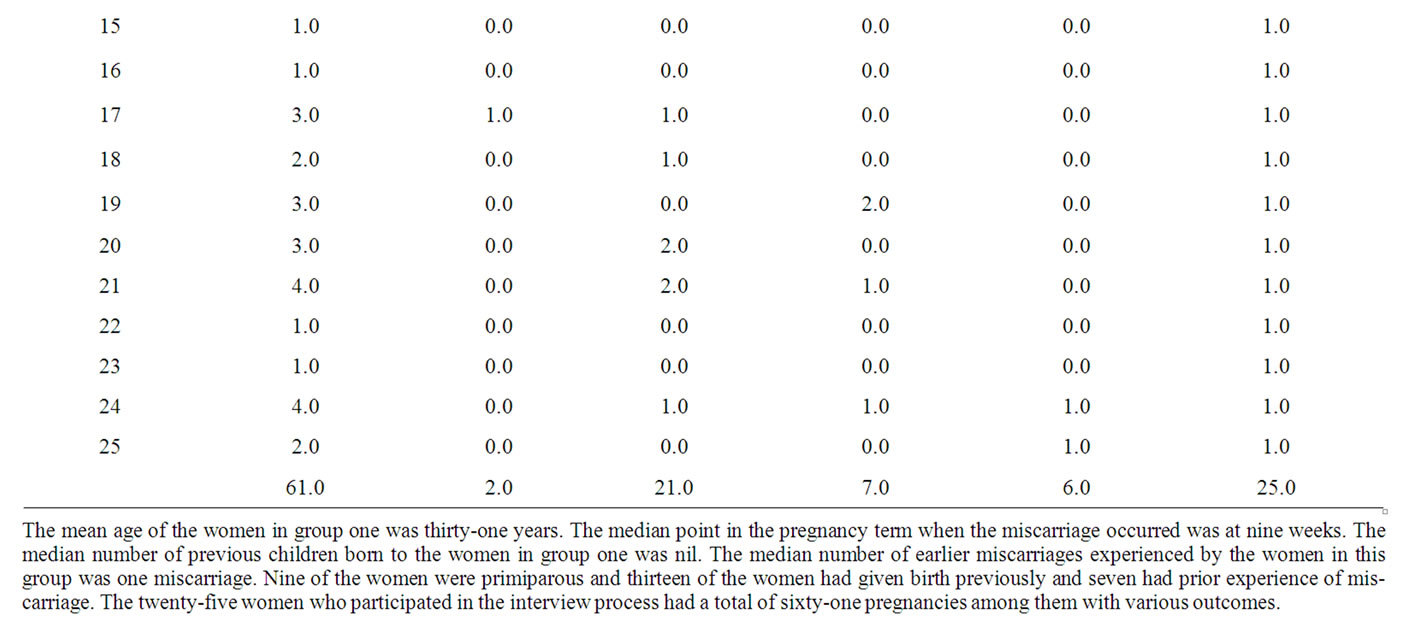

The mean age of the women in group one was thirtyone years. The median point in the pregnancy term when the miscarriage occurred was at nine weeks. The median number of previous children born to the women in group one was nil. The median number of earlier miscarriages experienced by the women in this group was one miscarriage. Nine of the women were primiparous and thirteen of the women had given birth previously and seven had prior experience of miscarriage. The twenty-five women who participated in the interview process had a total of sixty-one pregnancies among them with various outcomes. The interviews lasted a mean length of forty-five minutes from a range of twenty to hundred minutes. The main question in the interview that was asked of the participants was to relate to the interviewer the experience of their miscarriage (Table 1).

2.3. Statistics of participants in Group Two

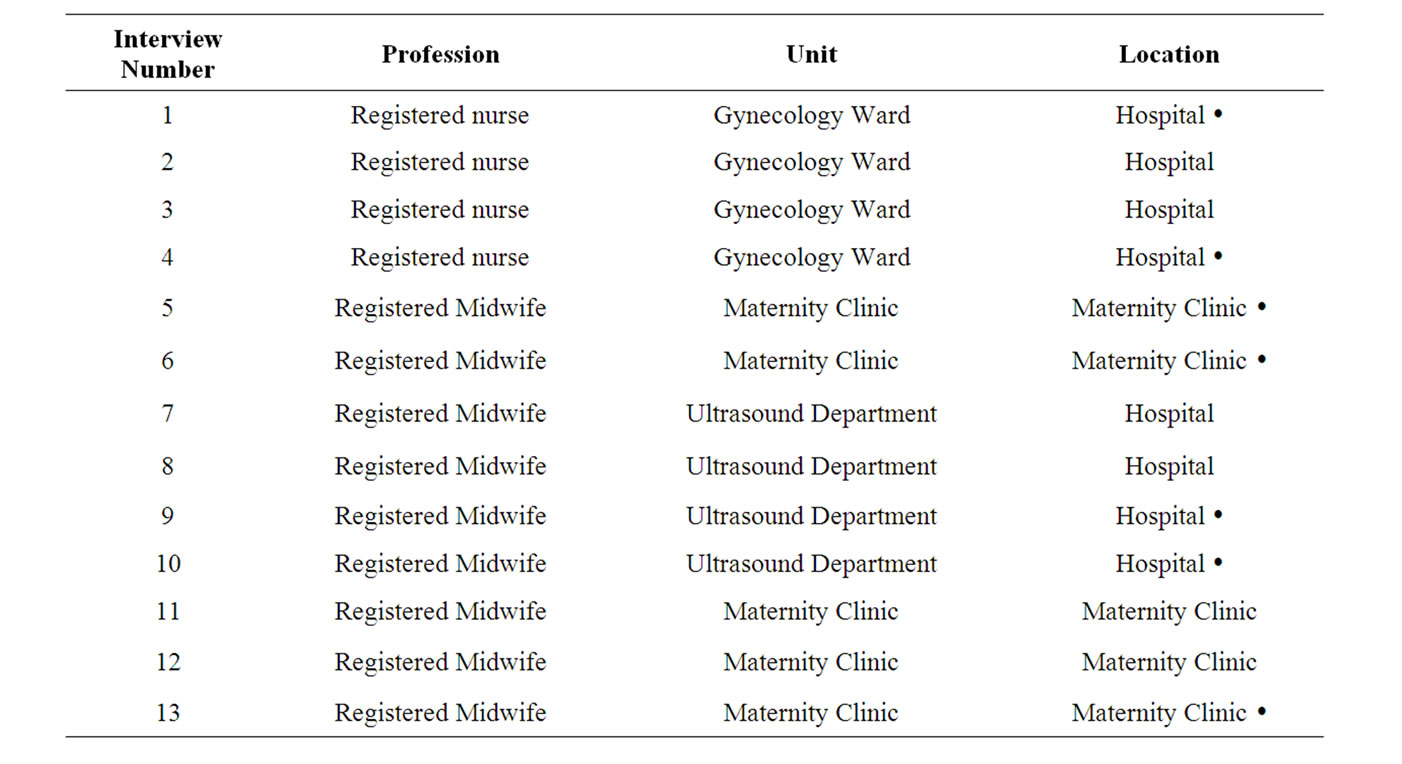

The participants in group two (caregiver) were the nurses and midwives selected from these three domains: four midwives at an ultrasound department, five midwives at

Table 1. Background Data for the 25 interviewees in the study.

a maternity clinic and four nurses at a gynecological ward in the Stockholm and Uppsala areas. These facilities are located within sixty miles of each other in large urban areas. The selection of interviewees from the Stockholm and Uppsala areas strengthens the reliability of this study because of the authors’ familiarity with the region. Smaller outlying communities were excluded because the authors’ were unfamiliar with the organizations outside of their immediate connections. The clinics that responded first were included in the study. The inclusion criteria were a minimum of two years professional experience and having cared for women who had been diagnosed with missed miscarriage during a routine ultrasound-scan in pregnancy week eighteen to twenty [4]. There were a total of thirteen 13 semi-structured interviews were used for data collection. The interviews were taped and lasted an average of forty-five minutes. Data was complied during the spring and summer 2007 (Table 2).

2.4. Data Analysis

Content analysis was applied to the verbatim transcripts of both the group one and group two interviews. The text was then analyzed in several stages and the first stage was that each interview was read and reviewed as a whole. The second stage consisted of meaning-bearing

Table 2. Interviews in chronological order, including background and place of employment. Interviews marked with Ÿ were held in Stockholm. Other interviews were held in Uppsala.

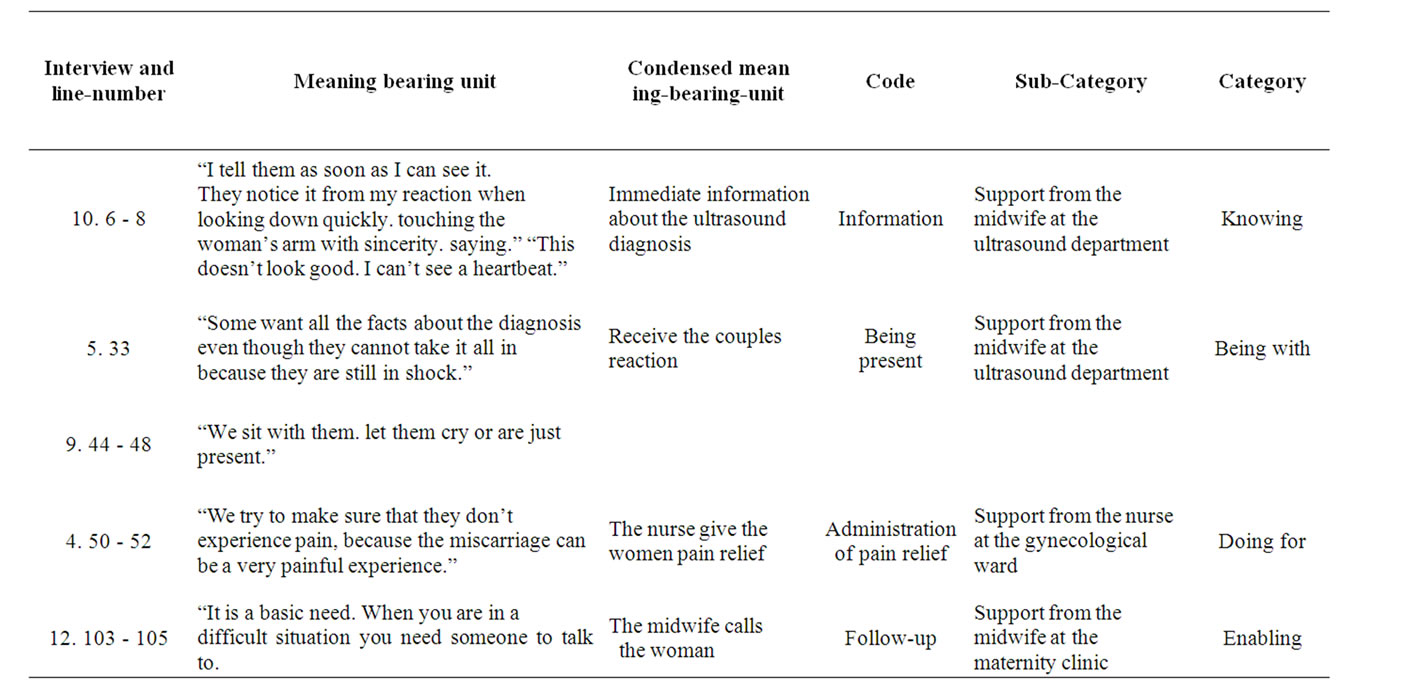

linguistic units being selected and assigned from the transcripts of both the group one and group two interviews. The linguistic units with similar meaning were grouped together [21] and they ranged from a few words to several lines of text [22]. The third stage of the analysis consisted of the discussion and coding of the linguistic units. Each meaning-bearing unit was given a code, sub categories and main categories [23] based on categories of the Swanson Middle Range Caring Theory [14] (Table 3).

The group one interviews were analyzed by author A. A. The group two interviews were analyzed by author C. J. both on the basis of the Swanson Middle Range Caring Theory [14].

In the results section each category of the Swanson Middle Range Caring Theory are presented as headlines. The findings from both group one and group two are described in the text and the confidence in the findings is confirmed with the remarks and some quotations from the transcripts of the interviews.

2.5. Ethical Considerations

The study of group one was approved by the regional ethics committee at the University of Gothenburg. Ethical permission for group two was received for from the Karolinska Institute’s Regional Ethical Examination Committee in Stockholm.

2.6. Consents Issues

The women and the caregivers signed a written informed consent form before participating in the study. The maternity clinics, hospitals, midwives, nurses and their supervisors have not been identified. The interviewees were told that the interviews and all the study material will be treated confidentially [24].

3. Results

3.1. The Caring Process according to Swanson’s Middle Range Caring Theory Maintaining Belief

3.1.1. Women

From the results of the interviews with the women it was determined that there was no standard way that each woman would react to the miscarriage. Each woman reacted in an individual manner and in a manner that suited her and her frame of reference.

Some women who have suffered a missed miscarriage have feelings of powerlessness and anger when they have felt that there was a problem with the pregnancy. but they were not believed. In some cases, there have been no available times for a control examination at the clinic or the gynecology ward.

“I have been so anxious and called around to several different places.”

Some women felt comfortable sharing their experience and their feelings about the miscarriage with others to various degrees while other women kept the experience to themselves and their intimate circle.

3.1.2. Caregivers

From the results of the interviews with the caregivers it was determined that some women felt that something was wrong with their pregnancy up to several weeks before it was confirmed that a missed miscarriage had oc

Table 3. Interview and line numbers. Meaning bearing units from various interview units in addition to condensed meaningbearing units. codes. sub-categories and categories are exemplified.

curred at an ultrasound examination. They no longer felt pregnant. they had fewer pregnancy symptoms and they have experienced minor bleeding. The midwife confirms the woman’s suspicions.

“Your feelings were right.”

The midwife confirms the woman’s sadness and grief over the loss of her pregnancy. She assists the grief stricken women to accept the diagnosis in spite of her shock.

It is recommended that the man remain with his partner during this time as they experience what has happened together and both receive the same information and answers to their questions. The couple helps each other to work through the initial period after the miscarriage and at the same time they attempt to work through the grief phase together and get ready to attempt a new pregnancy if they so desire.

3.2. Knowing

3.2.1. Women

An early miscarriage is typically diagnosed within the first twelve weeks of the pregnancy term as a result of the woman experiencing symptoms such as bleeding and abdominal cramping.

“I had a great amount of pain and bleeding.”

This is normally confirmed with an ultrasound examination. After the miscarriage they must be aware of the physical conditions necessary to become pregnant such as the timing in the menstrual cycle and when it will be physically appropriate to become pregnant again after recovering from the miscarriage.

3.2.2. Caregivers

A missed miscarriage may also be diagnosed several weeks later in the pregnancy term as a result of bleeding and cramping symptoms experienced by the woman or it may unfortunately come as a surprise result of the routine ultrasound examination performed at approximately the eighteenth week in the pregnancy term. During the routine ultrasound examination the couple and the midwife see the same images of the fetus on two separate monitors. First, the fetal heart activity is evaluated by the midwife and if the pregnancy is determined to be nonviable she must tactfully and honestly convey her observations. She makes physical human contact by touching the woman’s arm.

“I can’t see any heart activity.”

When the midwife makes the determination that the pregnancy is nonviable an obstetrician is summoned to confirm and explain the diagnosis and also to assist in answering any questions or concerns the couple may have at this point. Understandably they may be very concerned that the fetus has been deceased in the uterus for up to four or five weeks.

3.3. Being with

3.3.1. Women

Some women may find it extremely difficult when they receive the confirmation that they have had a miscarriage and others may feel that the experience was not so difficult.

“Seeing the ultrasound image was tough.”

Some women feel especially vulnerable and exposed when they are positioned for an intra vaginal examination on the examination table. Some women will experience particularly raw emotions at the sight of significant blood clots of tissue in the toilet and feel acute distress or panic.

3.3.2. Caregivers

During the registration interview at the maternity clinic, contact is made and a relationship is established. In the event the woman should express concern for symptoms that may indicate early or missed miscarriage the caregiver will attentively listen, reflect and determine an appropriate course of action. In the ultrasound department there is a special room where they can go after the ultrasound examination. There, the doctor and the midwife explain the diagnosis and the patient can ask questions.

“We sit with them let them cry or are just present.”

The midwives caring for the woman during the ultrasound scan and subsequent diagnosis of miscarriage stay with the couple and answer their questions and try to assist them in finding meaning in the experience in the context of being a significant life experience.

3.4. Doing for

3.4.1. Women

Women appreciate that the nurse provide their basic physical need such as providing toilet facilities. Providing a blanket and controlling food and drink intake.

Before the pregnancy termination one woman said.

“I appreciate a small gesture when the anesthesiologist wiping away my tears before anesthetizing.”

3.4.2. Caregivers

Doing for the caregiver may make appointments for a diagnostic examination or a follow up examination. It may be necessary to make arrangements for psychological evaluation or to provide counseling. If it is determined that an evacuation procedure is needed the caregiver may be in the position to make a phone call to arrange an earlier scheduled appointment to reduce the stressful waiting time for the woman. Perhaps the nurses at the gynecology ward could arrange a single room. There the nurse can establish contact and couple can talk undisturbed. The nurse regularly checks the couple as often she can to give them information even if they do not summon her and she gives the women pain relief.

“We try to make sure that they don’t experience pain. because the miscarriage can be a very painful experience.”

3.5. Enabling

3.5.1. Women

Post diagnosis the woman must be aware of some important information before making any decisions regarding to becoming pregnant again or not. First of all. they are informed that it is possible to become pregnant as early as three weeks after the miscarriage and that an early pregnancy is not a risk physically speaking. Psychologically, however, it is possible that a new pregnancy will bring on a return of fear and anxiety about the recent miscarriage.

“I felt unable to explain how I felt about it afterwards”

If the woman decides not to attempt to become pregnant immediately following the miscarriage, contraceptives are prescribed.

3.5.2. Caregivers

Midwives initiate the enabling process by taking their time during the ultrasound examination to give the couple time to assimilate their emotions and reactions after the diagnosis. It is helpful if the woman’s partner is invited into the conversation and they are posed questions regarding their thoughts and feelings.

Midwives perceived that the couple appreciated that they carrying out the follow-up, discussing the situation, making a telephone call and offering a return visit.

The midwives emphasize the importance of a social network that includes family and friends to talk with about their feelings regarding their experience.

“When life is tough, it is good to have a network to support you, when happiness turns to sorrow. Having the support of a social network can be an important part of the grieving process.”

4. Discussion

“Maintaining belief” means that the woman has the capacity to pass through the experience and see the future meaningful [14]. When the woman experiencing a miscarriage feels that there is something wrong with her pregnancy it is important and necessary that the caregiver responds to her feelings and fears. By encouraging the woman to talk through her feelings and staying with her through this process the caregiver helps the woman to maintain belief and give her a sense that she has at least a minimal amount of control of her situation. The caregiver encourages the couple to have the other partner present in order that they can work through this difficult situation together by supporting each other. As a result, the woman. the couple and the caregiver are able to give a positive meaning to a difficult life experience.

In some cases the woman may feel that the treatment has been insufficient and in these cases the care provider must feel compassion for the woman and confirm to her that it is not her fault. In order to give the couple the level of confidence that they need to confront the inevitable the nurses and midwives must maintain belief in the couple’s capacity to overcome the difficulty of the situation. With the proper care and understanding the women will find their own solutions in this unfamiliar situation. The midwife strives to be objective and administers care and information when the woman or the couples are in need of it. The midwife maintains and instills a positive attitude and realistic optimism.

Through “knowing” the caregiver identified with the woman’s wishes and her personal desire to be understood regarding the significant loss in her life [14]. In order to provide suitable care to a woman who has suffered a miscarriage the caregiver must have a broad background in both psychology and medicine. When the term knowing is used it is important that this means more than just medical knowledge [11,13-16]. Normal extensions of this discussion are about what possibly went wrong in the pregnancy and also discussing the possibility of a future pregnancy. The couple is evaluated with regards to the possibility of a new attempt to become pregnant in terms of their psychological readiness and wellbeing.

A relationship is established with the midwife when the woman signs in at the Maternity Healthcare Center and is strengthened and confirmed throughout the process of symptoms, diagnosis and treatment. In the event that the situation has evolved into a missed miscarriage, the caregiver has achieved a high level of credibility by being with the woman every step of the way. Caregivers of the women who have suffered a missed miscarriage sometimes have cases where the miscarriage is undetected until the routine ultrasound procedure, which usually occurs around the eighteenth week in the pregnancy term. Given this unfortunate situation, special knowledge is necessary in order to communicate tactfully to the couple that the fetus is deceased. A knowing caregiver is skilled in providing empathy and understanding to each of the woman based on their individual case and their individual needs. Women who were provided with a medical explanation of their miscarriage had reduced feelings of guilt. The care provider plays an important role in alleviating the experience of the miscarriage [25].

When the midwife establishes the sense of “being with” for the woman they are establishing a sense of a present emotional reality for the woman. The relationship focuses on the reality of the condition and the diagnosis [14]. Women are generally in various states of emotional distress. Depending on each individual reaction they may be in need of a tissue for their tears or the caregiver may have to remain with the woman to comfort them for some period of time. The caregiver normally asks about their feelings and concerns, or is just nearby. The nature the miscarriage experience may cause the woman to be distressed about future pregnancies, lost expectations for a baby and may trigger disturbing memories of past problems with pregnancy or child bearing. Some women may require counseling to work through their issues with their predicament.

Caregivers provide for the woman’s basic physical needs. Providing treatment and monitoring symptoms is an important service provided by the caregiver. Women are generally in various states of emotional distress. The final phase of the “doing for” aspect of care giving is the follow up examination to assess the woman’s recovery in terms of her physical, emotional and psychological health [14]. The follow up examination has been determined to be a positive contribution in the healthcare system to the wellbeing of the women who have suffered a miscarriage [6,8].

The end result of the process of providing care to a woman who has suffered a miscarriage is to “enable” the woman to focus on what exactly has transpired within her body and within her psyche [14]. Through the process of providing information and explaining all of the possible implications, the caregiver empowers the woman to use the experience within the context of her life as something to build upon and reduces the possibility that the experience has a debilitating effect on the woman. The process of enabling a woman who has experienced a miscarriage is one of listening and supporting, developing alternative courses of action, thinking things through clearly and giving feedback [11,13-16].

Once the woman has a sense of being enabled she is back in control of her body and back in control of her destiny. The woman’s fears of getting pregnant disappear with time. She can begin taking contraceptives to further gain control of her body and help with any anxiety she may have about getting pregnant.

She can allow her social network to support her on her road to recovery. The caregiver has a lot of impact on the woman’s capacity to work through the miscarriage [4]. By providing those services to the woman that she cannot provide for herself the caregiver can give the woman a greater sense of wellbeing [14]. The experience of wellbeing increases with the care given. Well-being after miscarriage involves being in a safe place, receiving information, reducing the pain of fear, sadness, and expressing yearning for the lost and for the loved. Experience of wellbeing involves living subjectively, meaningfully and experiencing a feeling of wholeness [11,13-16].

5. Conclusions

Swanson’s Middle Range Caring Theory includes being emotionally present, respecting the women’s dignity.

being competent, meeting each individual woman’s needs and being objective. Midwives need to give the women clear information and add to their better understanding regarding their new life situation. Giving the women selfesteem, keeping a positive attitude, and showing realistic optimism are important. Midwives provide understanding to the whole situation, propose reflection, being trustworthy for the women and improve their wellbeing. Given the proper care every woman has the power within herself to experience a life event such as miscarriage without diminishing her life experience and wellbeing.

6. Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to all the women, midwives and nurses who participated and communicated their knowledge and experiences to us.

REFERENCES

- A. Adolfsson and P. G. Larsson, “Cumulative Incidence of Previous Spontaneous Abortion in Sweden in 1983- 2003: A Register Study,” Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand, Vol. 85. No. 6, 2006, pp. 741-747. doi:10.1080/00016340600627022

- A. Adolfsson, P. G. Larsson, B. Wijma and C. Berterö, “Guilt and Emptiness: Women’s Experiences of Miscarriage,” Health Care for Women International, Vol. 25. No. 6, 2004, pp. 543-560. doi:10.1080/07399330490444821

- M. H. Hutti, “Social and Professional Support Needs of Families after Perinatal Loss,” Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic & Neonatal Nursing, Vol. 34. No. 5, 2005, pp. 630-638. doi:10.1177/0884217505279998

- C. Jansson and A. Adolfsson, “Swedish Study of Midwives’ and Nurses’ Experiences When Women are Diagnosed with a Missed Miscarriage during a Routine Ultrasound Scan,” Sexual & Reproductive Healthcare, Vol. 2. No. 1, April 2010, pp. 67-72. doi:10.1016/j.srhc.2010.01.002

- J. Cullberg, “To Meet People in Crisis.” In: J. Cullberg and T. Lundin, Eds., 5th Edition, Crisis and Development, Nature and Culture, Stockholm, 2006, pp. 156-178.

- A. Adolfsson, C. Berterö and P. G. Larsson, “Effect of Structured Follow-up Visit to a Midwife on Women with Early Miscarriage: A Randomized Study,” Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica, Vol. 85. No. 3, 2006, pp. 330-335. doi:10.1080/00016340500539376

- K. Stratton and L. Lloyd, “Hospital-Based Interventions at and Following Miscarriage: Literature to Inform a Research—Practice Initiative,” Australian and New Zealand Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Vol. 48. No. 1. February 2008, pp. 5-11. doi:10.1111/j.1479-828X.2007.00806.x

- K. M. Swanson. H. T. Chen. J. C Graham. D. M Wojnar and A. Petras. “Resolution of Depression and Grief during the First Year after Miscarriage: A Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial of Couples Focused Interventions,” Journals of Women’s Health, Vol. 18, No. 8, August 2009, pp. 1245-1257. doi:10.1089/jwh.2008.1202

- N. Brier, “Grief Following Miscarriage a Comprehensive Review of the Literature,” Journals of Women’s Health, Vol. 17, No. 3, April 2008, pp. 451-464.

- K. M. Swanson. Z. A. Karmali, S. H. Powell and F. Pulvermakher, “Miscarriage Effects on Couples’ Interpersonal and Sexual Relationships during the First Year after Loss: Women’s Perceptions,” Psychosomatic Medicine, Vol. 65, No. 5, 2003, pp. 902-910. doi:10.1097/01.PSY.0000079381.58810.84

- K. M. Swanson, “Research-Based Practice with Women who have had Miscarriages,” Image: Journal of Nursing Scholarship, Vol. 31. No. 4, 1999, pp. 339-345. doi:10.1111/j.1547-5069.1999.tb00514.x

- K. M. Swanson-Kauffman, “A Combined Qualitative Methodology for Nursing Research,” Advances in Nursing Science, Vol. 8. No. 3, 1986, pp. 58-69.

- K. M. Swanson, “Nursing as Informed Caring for the Well-being of others,” Image: Journal of Nursing Scholarship, Vol. 25, No. 4, 1993, pp. 352-357. doi:10.1111/j.1547-5069.1993.tb00271.x

- K. M. Swanson, “Empirical Development of Middle Range Theory of Caring,” Journal of Nursing Research, Vol. 40, No. 3, 1991, pp. 161-166.

- K. M. Swanson, “Effects of Caring. Measurement and time on Miscarriage Impact and Women’s Well-being.” Journal of Nursing Research, Vol. 48, No. 6, 1999, pp. 288-298. doi:10.1097/00006199-199911000-00004

- K. M. Swanson-Kauffman, “Caring in the Instance of Unexpected Early Pregnancy Loss,” Topics in Clinical Nursing, Vol. 8, No. 2, 1986, pp. 37-46.

- S. Cobbs, “Social Support as a Moderator of Stress,” Psychosomatic Medicine, Vol. 38, No. 5, 1976, pp. 300-314.

- J. Watson, “Nursing: The Philosophy and Science of Caring,” Little. Brown and Company, Boston, 1979.

- J. Watson, “Nursing: Human Science and Human Care,” Appleton-Century-Crolls, Norwalk, 1985.

- P. Benner, “From Novice to Expert,” Addison-Wesley, Menlo Park, 1984.

- S. Kvale and S. Brinkmann, “The Qualitative Research Interview,” 2nd Edition, Studentsliterature, Lund, 2009.

- M. Q. Patton. “Qualitative Evaluation Research Methods,” 2nd Edition, Sage Publications Ltd., Newburry Park, 2002.

- K. Krippendorff, “Content Analysis: An Introduction,” 2nd Edition, Sage Publications Ltd., London, 2004.

- World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. “Helsinki: The Association 1964 - 2008,” January 10th 2008. http://www.wma.net/e/policy/b3.html

- R. K. Simmons, G. Singh, N. Maconochie, P. Doyle and J. Green, “Experience of Miscarriage in the UK: Qualitative Findings from the National Women´s Health Study,” Social Science & Medicine, Vol. 63, No. 7, October 2006, pp. 1934-1946. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.04.024