Advances in Infectious Diseases

Vol.2 No.4(2012), Article ID:25488,3 pages DOI:10.4236/aid.2012.24024

A Mass Shadow on Chest X-Ray in a 40-Year-Old Man: What’s Your Diagnosis?

![]()

1Department of Internal Medicine and Infectious Diseases, Farhat Hached Hospital, Sousse, Tunisia; 2Department of Pathology, Farhat Hached Hospital, Sousse, Tunisia.

Email: hachfi_wissem@hotmail.com

Received April 22nd, 2012; revised May 23rd, 2012; accepted June 25th, 2012

Keywords: Actinomycosis; Lung infections; Thoracic Neoplasms

ABSTRACT

A 40-year-old man presented recurrent cough and bloody sputum for 4 months. Chest X-ray showed a large mass in the right upper lobe. Histopathologic examination of tissue from percutaneous biopsy of the lesion revealed actinomycotic granules and branching filamentous bacteria, and therefore pulmonary actinomycosis was diagnosed. These findings suggest that pulmonary actinomycosis should be included in the differential diagnosis of a mass on a chest X-ray film.

1. Introduction

Actinomyces spp are facultative anaerobic gram-positive, filamentous, bacteria that normally colonize the mouth, colon, and urogenital tract. The adjacent tissues will become infected only if there is a loss of mucosal integrity [1]. Actinomycosis is a rare disease, characterized by local suppuration and an extensive fibro-inflammatory process. The cervicofacial and pelvic areas are the most commonly areas affected, lung localization is much rare [2].

2. Observation

In July 2008, a 40-year-old man with no past medical history presented with a 4-months history of cough with mucopurulent, bloody sputum. He denied fever, chills, night sweats, fatigue, weight loss, chest pain or dyspnea. He was a construction worker who has never smoked nor consumed alcohol. He didn’t receive any biphosphonates. On admission, his temperature was 37.2˚C, his blood pressure was 110/60 mm Hg, his pulse rate was 70 beats/ min, and his respiratory rate 16/min. Findings of the physical examination were unremarkable except for caries on the left lower second premolar tooth.

Laboratory tests revealed the following values: white blood cell count, 8600 mm3; hemoglobin, 12.4 g/dl, platelet count, 385000 mm3; erythrocyte sedimentation rate, 14 mm at one hour, and C reactive protein, 22 mg/L. Serum glucose, creatinin, alanine aminotransferase and aspartate aminotransferase were in normal range.

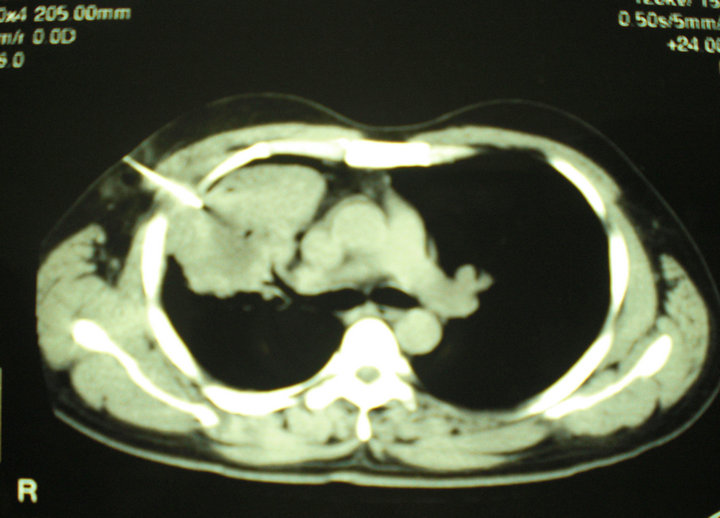

Chest radiography and contrast-enhanced Computed Tomography (CT) scan of the chest (Figure 1) showed large, cavitary, irregular, mass-like consolidation in anterior segment of right upper lobe of the lung, with adjacent pleural thickening, and enlarged necrotic mediastinal lymph nodes. There was neither pleural effusion nor chest wall involvement. Fiberoptic bronchoscopy was not performed. CT scan guided needle aspiration of the pulmonary lesion obtained grey-green pus. Microscopic examination of the specimen was negative for Gram’s stain, acid-fast bacilli and fungal agents. Culture of pus grew polymorph flora.

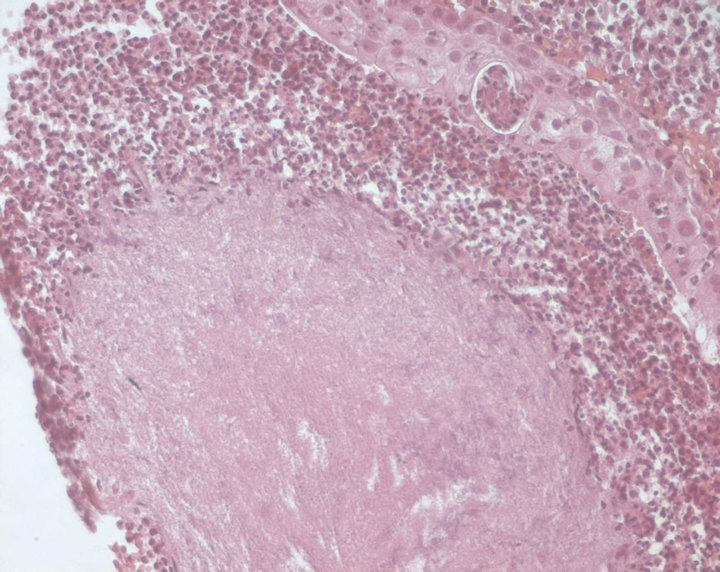

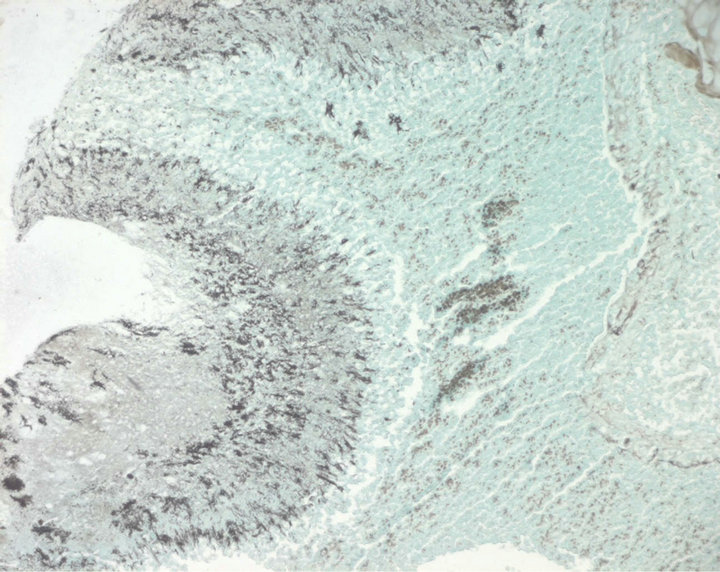

Lung cancer was suspected, CT guided percutaneous biopsy of the right upper lobe lesion was performed. Histopathologic examination showed actinomycotic granules surrounded by suppurative polymorphonuclears infiltrate stained with Haematoxylin-Eosin (Figure 2), and thin bacterial filaments, radially oriented, stained with Gomori-Grocott (Figure 3). No granuloma, carcinoma or sarcoma was seen. Neither cervical nor pelvic CT scan were performed to rule out disseminated disease. The patient was treated with intravenous (IV) penicillin G 24 million units daily for 4 weeks then by oral amoxicillin 3 g daily. Dental caries were treated. Cough and hemoptysis were almost resolved and the patient was discharged after six weeks of antibiotic treatment. He received oral amoxicillin 3 g daily for 12 months followed by doxycycline 200 mg daily for 6 months. Amoxicillin was switched to doxycycline because the patient preferred a one pill daily regimen. Clinical improvement was noted slowly

Figure 1. CT scan of the chest. Large, cavitary, mass-like consolidation in the anterior segment of the right upper lobe of the lung.

Figure 2. Haematoxylin-Eosin stain ×400. Actinomycotic granules surrounded by suppurative polymorphonuclears infiltrate.

Figure 3. Gomori-Grocott stain ×100. Bacterial filaments radially oriented, colored in black.

and his clinical course has remained unremarkable until March 2011.

3. Discussion

There is a little frequency data on all forms of actinomycosis in the literature. The yearly incidence was 1:100,000 in Germany in the 1960s and 1:300,000 in the Cleveland area during the 1970s [2]. This incidence appears to have declined markedly in the last three to four decades [3]. Pulmonary actinomycosis constitutes 15% to 20% of the cases of actinomycosis [3]. Its incidence is more frequent in males in the fourth to fifth decades but not in immunocompromised patients [3]. Risk factors include smoking, alcohol abuse, chronic pulmonary diseases, and poor dental hygiene [4,5]. The main symptoms are productive cough and hemoptysis. Fever and weight loss may be suggestive of disseminated disease [3]. The average duration of illness before diagnosis is six months [3,4]. The characteristic findings on chest radiography and CT scan include airspace consolidation involving the upper lobe, mild enlargement of mediastinal lymph nodes, and mild pleural thickening adjacent to the airspace consolidation [6]. The following typical clinical and radiographic features were present in our patient.

Nevertheless, even when the clinical suspicion is high, pulmonary actinomycosis can resemble a spectrum of lung pathologies mainly lung abscess, tuberculosis and malignancy because of similar chronic symptoms and radiographic findings [3,6].

Diagnosis of actinomycosis is generally hampered by the difficulty in isolation of the bacterium [6]. Hence, lung biopsy is usually necessary to obtain samples for histological and microbiological confirmation of pulmonary actinomycosis [3]. Ultrasound or CT guided percutaneous biopsy is a simple and effective diagnostic technique and reduces the number of unnecessary resections [3]. It is still important to alert the pathologist of the suspected diagnosis, as special stains may have to be used to look for the organism [3]. Sulfur granules, long regarded as a histological hallmark of actinomycosis, are very strongly suggestive of the diagnosis. These are conglomerate organisms that have basophilic masses with radiating rosette of eosinophilic clubs on the surface [6]. However, they are not entirely specific to actinomycosis, since these granules can also be found in nocardiosis and aspergillosis [7].

In our patient, Pus culture grew polymorph flora but didn’t yield Actinomyces. Pulmonary actinomycosis was diagnosed on the presence of actinomycotic granules and bacterial filaments, together with favorable outcome with specific treatment.

The recommended therapy for pulmonary actinomycosis is IV penicillin G 18 - 24 million units IV for 2 to 6 weeks followed by oral amoxicillin 2 g PO daily for 6 to 12 months. Alternatives to penicillin include doxycycline 200 mg PO daily, erythromycin 2 g PO daily, and clindamycin 1800 mg PO daily [6,8]. Surgery is necessary to treat abscesses, empyemas with discharging fistulas, or life-threatening hemoptysis [9]. With appropriate therapy, cure rate is 90%. Untreated, the mortality rate is 75% to 100%. Our patient was treated with IV penicillin G for 4 weeks then by oral amoxicillin for 12 months followed by doxycycline for 6 months. There was no need for surgery. The clinical course was successful.

4. Conclusion

The diagnosis of pulmonary actinomycosis requires a combination of clinical and radiologic features with microbiologic culture of relevant specimens. Biopsy of the lesion with histologic examination may be necessary to differentiate actinomycosis from other diseases mainly tuberculosis and malignancies. When the infection is recognized early and adequate treatment is given, like in our patient, prognosis is excellent

REFERENCES

- J. Moses, G. F. Bonomo, D. E. Wenlund, T. S. Halldorddon and J. P. Connelly, “Actinomyces in Childhood,” Clinical Pediatrics, Vol. 42, No. 2, 1967, pp. 221-226.

- D. Bennhoff, “Actinomycosis: Diagnostic and Therapeutic Considerations and a Review of 32 Cases,” The Laryngoscope, Vol. 94, No. 9, 1984, pp. 1198-1217.

- G. F. Mabeza and J. Macfarlane, “Pulmonary Actinomycosis,” European Respiratory Journal, Vol. 21, No. 3, 2003, pp. 545-551. doi:10.1183/09031936.03.00089103

- M. Kolditz, J. Bickhardt, W. Matthiessen, O. Holotiuk, G. Hoffken and D. Koschel, “Medical Management of Pulmonary Actinomycosis: Data from 49 Consecutive Cases,” Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy, Vol. 63, No. 4, 2009, pp. 839-841. doi:10.1093/jac/dkp016

- S. Chouabe, D. Perdu, G. Deslée, D. Milosevic, E. Marque and F. Lebargy, “Endobronchial Actinomycosis Associated with Foreign Body: Four Cases and a Review of the Literature,” Chest Journal, Vol. 121, No. 6, 2002, pp. 2069-2072. doi:10.1378/chest.121.6.2069

- B. D. Sarodia, C. Farver, S. Erzurum and J. R. Maurer, “A Young Man with Two Large Lung Masses,” Chest Journal, Vol. 116, No. 3, 1999, pp. 814-818.

- N. Shinagawa, E. Yamaguchi, Takahashi and M. Nishimura, “Pulmonary Actinomycosis Followed by Pericarditis and Intractable Pleuritis,” Internal Medicine, Vol. 41, No. 4, 2002, pp. 319-322. doi:10.2169/internalmedicine.41.319

- M. Bennett and Dolin, “Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases,” 6th Edition, Elsevier, Netherlands, 2005.

- J. C. Choi, W. J. Koh, T. S. Kim, et al., “Optimal Duration of IV and Oral Antibiotics in the Treatment of Thoracic Actinomycosis,” Chest Journal, Vol. 128, No. 4, 2005, pp. 2211-2217. doi:10.1378/chest.128.4.2211