Open Journal of Modern Linguistics

Vol.04 No.04(2014), Article ID:51137,9 pages

10.4236/ojml.2014.44049

The Use of Indigenous Language in Radio Broadcasting: A Platform for Language Engineering

T. A. Akanbi, O. A. Aladesanmi

Department of Linguistics and Nigerian Languages, Ekiti State Unversity, Ado-Ekiti, Nigeria

Email: yemiakanbi@gmail.com, bolaaladesanmi@gmail.com

Copyright © 2014 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received 4 August 2014; revised 2 September 2014; accepted 17 October 2014

ABSTRACT

This paper discusses the practical ways by which language users make use of coinage in order to find expressions for the day-to-day usages of common words, but which albeit are found in other languages like English. The media practitioners are exposed to using words to capture their intensions. Since these practitioners are faced with audience that are of local language, they are constrained to look for words that will express what goes on in the world around them. In an age of Information and Communications Technology (ICT), many of the words used are computer compliant, therefore, it behoves the people interacting with the populace through language to look for those codes that will carry their messages to their audience in the way that will go in conformity to the understanding of their audience. This paper, therefore, looks at those coinages and proposes that they should be collated and integrated into Yorùbá vocabulary system for the use of people in a general context.

Keywords:

Coinage, Media Practitioners, ICT, Computer, Audience

1. Introduction

Electronic media, especially radio, is an important tool in the dissemination of information to the audience in every setting. Radio, as one of the electronic media has been playing a significant role since the world war years. It has helped in the maintenance of peace, unity and harmony among the people the world over. This medium has always been fallen back to during any emergency period or any time that the rulers want to mobilise the ruled into a particular issue.

Radio as an electronic medium, and like any other media, serves three major purposes. These major purposes include informing, educating and entertaining. One important factor that has always made these tripod purposes realisable is the use of language. Therefore, if particular information is to be disseminated and appropriate language is not used, then, such information may not reach the audience in a way that they will be able to understand. Language, therefore, plays a major role in the usefulness of electronic media to the populace. As such, the language employed by a media house goes a long way in determining the listenership strength and effectiveness of its services.

Most of the electronic media operating in Nigeria are English based. That is, the major language used in many of Nigerian electronic media is English. This is so since English language has grown all over the world as the predominant language at the expense of other languages. English, as a medium of disseminating information, enjoys high prestige to the detriment of the indigenous languages spoken in Nigeria since it remains the language of officialdom. This, and some other reasons which do not form the focus of this paper, makes the electronic media in Nigeria stick to using English. If there is any use of indigenous language in such electronic media at all, it only carries about five per cent of the whole period allotted to news and entertainment and other things in the station.

2. The history of radio in Nigeria

As reported by Wikipedia (www.edutech402.blogspot.in/20) of 2012, radio started in Nigeria with the introduction of Radio Distribution System in the year 1933 in Lagos by the British colonial government under the Department of Post and Telegraphs (P & T). The Radio Distribution System (RDS) was a reception base for the British Broadcasting Corporation and a relay station, through wire systems, with loudspeakers at the listening end. In 1935, the Radio Distribution System (RDS) was changed to Radio Diffusion System (RDS). The aim was to spread the efforts of Britain and her allies during the Second World War through the BBC. The Ibadan station was commissioned in 1939, followed by the Kano station in 1944. Later, a re-appraisal of radio broadcast objectives gave birth to the establishment in 1950 of the Nigerian Broadcasting Service (NBS). The NBS began broadcast in Lagos, Ibadan, Kaduna, Kano and Enugu on short wave and medium wave transmitters.

Through a Bill by the House of Representatives, the Nigerian Broadcasting Corporation (NBC) was established in 1956. The NBC took up the responsibilities of radio broadcast in Nigeria. The Federal Radio Corporation of Nigeria (FRCN) was established in 1978. The Voice of Nigeria (VON) which served as the external service was established in 1990. With the creation of more states and each state wanting to propagate its people and culture, the pace for radio broadcast began in Nigeria and has spread fast across the length and breadth of the nation. Each state owns and operates at least one radio station. Eventually, individuals also started to establish private radio stations.

However, as many radio stations there are in Nigeria, the major medium of communication is only English. Though there are programmes aired in the various surrounding indigenous language(s), such programmes occupy a lesser percentage when compared with the totality of the programmes rendered or aired in English. Even the various FM radio stations established during the era of Obasanjọ as the president, none of them is wholly an indigenous language station. This trend continues until the Osun State Government, in 2005 established Orisun FM.

Orisun FM 89.5

Orisun FM was established by the Osun state government in 2005. The station is unique in that the medium of communication is wholly the indigenous Yorùbá language. Yorùbá which is the language of the surrounding communities is used as the medium of communication. More of the uniqueness of the station is premised on the use of Standard Yorùbá (SY) devoid of dialectical variation. Noting this fact, Opeyemi (2013: p. 32) says that:

“Impressively, the station broadcasts in rich Standard Yorùbá language as it beams out rich cultural programme laced with innovations. The radio station teaches both the language and the culture of the Yorùbá nation. This endears the radio station to quite a major chunk of the South Westerners and many a listener in other neighbouring states”.

By its use of SY, this does not mean that the station does not allow other dialects to be spoken on the radio station. There are programmes designed for this. Such request programmes like “Ìkini lédè Èkìtì, Ìkini lédè Ọ̀yọ̀, Ìkini lédè Ifẹ̀, Ìkini lédè Ìgbómìnà, Ìkini lédè Ìjẹ̀bú” (i.e. greetings in the dialect of...) etc. are major request programmes where the presenters aired the programmes in the dialects mentioned. Apart from this, some individuals are often invited to particular programmes where their dialects are allowed to be spoken.

The fact that all programmes at Orisun FM are aired in Yorùbá calls for devising a meta-language for various concepts, notions and nomenclatures that are supposedly of different language origin. More so, Nigeria, which is a British colony uses English as its lingua franca therefore, most of the concepts that must be integrated into the immediate surrounding indigenous language come from the English language. As a result of this, language engineering comes into the fore. In this instance, the media people have been put into tremendous work in developing the Yorùbá language. This action on the part of the electronic media people has complemented those of the academia. In commending their efforts towards this activity Yusuff (2008: p. 239) has this to say:

“One cannot but be impressed by the extent to which the media has enriched the lexicon of the Yorùbá language through the formation of terms for modern concepts and notions intuitively and spontaneously. They strive to satisfy the adequacy criterion because they have little or no choice than to do so, since they must inform the public of events as soon as they occur”.

This commendation is very appropriate for the media people especially those who work in indigenous language radio stations in Nigeria. Even though, as Yusuff (2008) points out, “the level of appropriateness and effectiveness of the terms generated cannot be guaranteed and therefore deserves some attention”, one cannot say they have not put in some commendable efforts in the area of language engineering.

3. Language engineering

Language engineering is a result of the advent of Information and Communication Technology (ICT). This aspect is noted by Akanbi (2012: p. 5) when he says that:

“Language engineering is a new and developing area of linguistics. It is an aspect of linguistics which came up as a result of the advent of Information and Communications Technology (ICT). Since language is pervasive, there is the need to synthesise language with ICT, hence, the development of language engineering as a discipline and a branch of linguistics”.

Capo (1990: p. 1) in defining the concept of language engineering sees it as:

“that domain of applied linguistics concerned with the design and the implementation of strategies (i.e. conscious and deliberate steps) towards the rehabilitation and optimal utilization of individual languages”.

Delving further on the issue of language engineering vis-a-vis language development, Capo (1990: pp. 1-2) further asserts that:

“Language engineering is a continuing and dialectic process including orthography design corpus planning, material development, encouragement of language use at all levels to account for and communicate the changing experiences of the speakers as well as aspects of human legacy called knowledge”.

Since new and emerging idea, which have their origin from the source language, must be expressed in the local language, there is the need to find an equivalent translation that will capture the essence of the borrowed word in the borrowing language. It is the belief of some scholars that Yorùbá language is too impoverished to accommodate emerging ideas from languages like English. This belief is expressed in the word of Owolabi (2006: p. 17) that:

“If anything, our local languages are constrained in a number of ways. Most of them are not developed enough to accommodate the intricacies and inflections that a dynamic language should have. New ways of doing things especially in the areas of science and technology as well as information technology can hardly be captured by the lexis and structure of our indigenous languages”.

This assertion may not stand in the face of the various efforts being made by the university scholars in devising nomenclatures for hitherto concepts that are of various discipline origin. Words for concepts in fields like Engineering, Medical, Science, Technology, Linguistics, etc. are being provided. For instance, Yorùbá scholars have at various times, devised metalanguages for various concepts that have surfaced in the educational terrain of Nigeria educational system (see Bamgbose, 1992; Awobuluyi, 1994). The work of these scholars on Yorùbá metalanguage is still ongoing1.

However, all the works that have been carried out on metalanguage are limited to educational concepts alone. This is where this work is different from those that have been done; in that this present work looks beyond educational circle and delve into other areas which include politics, sports, computer based notions, etc.

In the sections that follow, we will endeavour to present these various areas, present our data, analyse them and show the implications this has on the development of Yorùbá language.

3.1. Deriving words in language engineering

Language engineering in relation to deriving appropriate words for certain notions and concepts has three major consequences on language. These consequences result in 1) Lexical addition; 2) Lexical percolation and 3) Semantic change (cf. Yusuff, 2008; Akanbi, 2011). We shall refer to these consequences as we go on in this paper.

3.2. Methods of derivation in language engineering

In this section, we shall look at various neologism that has come into Yorùbá language through the media and attempt to do both the syntactic and solinguistics analysis of them. The word neologism means a newly coined word, phrase or expression put forward for usage. Such neologism may be in form of a sentence, phrase or a lexical item used to capture the essence of the meaning of the word in a borrowing language. The implication of this shows that language is not monolithic, every language is mutable. And when a word is coined, it enhances the vocabulary of a borrowing language. In some cases, the word newly coined may show an alternative meaning for the original word in the other language. However, such new word must be able to express the idea carried by the word in the source language.

When a concept comes into existence, a name is found for it. The name so found has an unprecedented chance of being heard beyond the confines of the place where the word originates. This is made possible by the help of series of computer devices which has made the whole world to become one global village. Some newly coined words have the tendency to survive very long due to certain reasons which include; usefulness, user-friendliness, exposure, longevity of the concept, and the potential association they may have with the populace. All these are primary contributors to the survival of new words. If it is like this, then words must be coined for such concepts in some other languages apart from the source language.

3.3. The coinage of new words for new concepts

It is never an overstatement to say that the world of computer in globalization has brought with it new concepts. The introduction of these new concepts, therefore, has increased the vocabulary of virtually all the world languages. It means therefore, for any newspaper, electronic media houses, journal and news magazines being operated in the local languages to thrive and survive, they must look for and make use of words for these new concepts and names in the borrowing language. We shall present our data2 in this section, while in the other section, we shall do the syntactic and socioliguistic analyses of the new words.

3.3.1. New words coined in sentential forms

The following are the new neologism brought into Yorùbá language (see table 1).

3.3.2. Data analysis

The data in “A” cover certain areas of human inventions and activities. Areas like technology, politics, football, economy, education, sports, law, etc. were touched in the data. For instance, data number 1, 26, 27 in “A” has to do with GSM operation, a technological invention. Other words that relate to technological invention include those in (6, 7, 8, 18, 26, 27, 30). The names have to be coined in order that the audience who do not understand English language would understand what the newscaster is referring to. In the area of politics, we have words like those in (14), while data in (16, 23, 24 and 25) relate to sports. On the health related words, we have those in 12, 13, 15); while those in (20 and 21) are those for the economy. On the part of education, we have words in (4, 5, 9 and 10). We also have some that relate to corruption (3), an endemic problem that is eating deep into the fibre of the society.

In looking at the various coinages we have in the data “A”, it will be observed that there are no one word coinage. All the words that are there in the data are phrases, clauses and even sentences. The reason for using this method borders on the fact that there is no one word that could capture the meaning essence of the concept that the broadcast house wants to disseminate to its audience. And if the audience will understand the

Table 1. Sentential coinage words strategy (DATA “A”).

issues that are rendered in another language (i.e. the source language which is English), the words that will capture the meaning must be sought for and used.

There is no doubt that the development of the Yorùbá language has made it imperative to derive words that hitherto are rendered in English into the vocabulary system of the Yorùbá language. Bamgbose (1986: p. 29) notes this fact and says that “It is well known in language that the more it is used in several domains, the greater its development and expansion”.

The data presented in “A” and those that will still be presented shows that the development of Yorùbá vocabulary in capturing the issue of technology is not a work limited to the four walls of the university but the work of all those that are using the Yorùbá language in every domain. This in essence, makes the assertion of Yusuff (2008: p. 85) that:

“The task of ensuring that Yorùbà language is developed and modernized to meet contemporary challenges posed by science, technology, globalization and modern civilization rests squarely on the shoulders of Yorùbá linguists” cannot be all encompassing.

We do not agree with Yusuff’s (op. cit.) on the fact that many of the derived and coined words used by the indigenous languages broadcasters (Yorùbá language, especially) are coined by the broadcasters themselves. Therefore, in finding words for the new concepts, the broadcasters must also be co-opted into whichever committee is constituted saddled with the responsibility of finding words for new concepts.

Before going into the syntactic analysis of the data presented, we will present the second part of our data which shows the one word coinage of words for concepts.

3.4. One word coinage

The following are the examples of one word coinage (see table 2).

All the words in the above data are one word coinages. Their advent is as a result of technological advancement which brought a new role to Yorùbá usage. In some cases, the coinage may not be a result of technology but a result of new phenomenon coming into the language community. Therefore, the various domains of use to which Yorùbá language is subjected to have made it imperative that new words must be sort for new concepts. This will afford the Radio Stations broadcasting in local languages fulfill their role within the society in which they are established. Not only this, they will be able to serve their audience adequately well.

In our data “B” above, we have the derivation of single words. In some cases some of these single words do not of the same structure with the English equivalent of it. What we are saying is that in some instances, the English equivalent of the Yorùbá words may be phrases or compound words. For instance numbers (16 and 17) i.e. “Waste Management Board” and “Environmental Sanitation” in the data “B” above have one word in its Yorùbá translation/derivation which are “kólẹ̀kódọ̀tí”and “gbálégbáta” respectively.

As will be seen in the next section, some coined words are derived through onomatopoeia where the words are derived in consonance with the sound made by the concept. In the sections following, we look at the syntactic and morphological analysis of the various words that appear in our data “A” and “B” above.

3.4.1. Syntactic Analysis

As we have mentioned earlier, even though all the coinages in the Data “A” are regarded as one word, each of the coinages are more than one word in structure. However, as observed, the coinages follow the syntactic structure of Yorùbá phrases or sentences. The syntactic structure of Yorùbá like English is Subject-Verb-Object (SOV). Each of the words in the Data “A” follows this pattern of sentence formation in Yorùbá. It means then that any word formed as a translation of another in the source language must be done in such a way that the

Table 2. One word lexical coinage strategy (DATA “B”).

audience of the radio station must be able to know the meaning of the word; even when the word is a new one in the Yorùbá vocabulary. We shall look at some of the words in Data “A” for analysis.

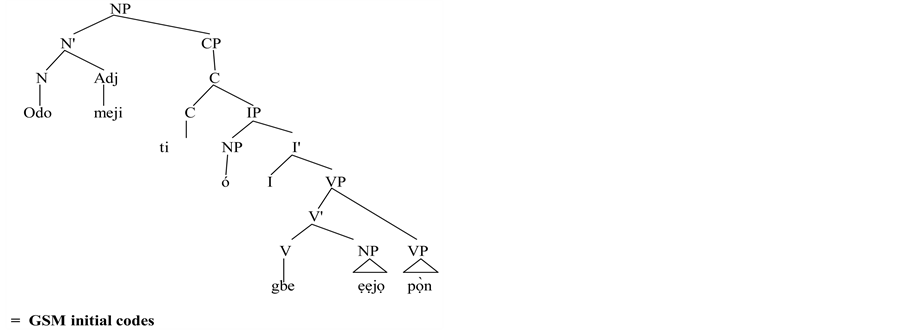

(1) Òdo-méjì-tógbé-ẹẹ́jọ-sáàrin GSM initial codes

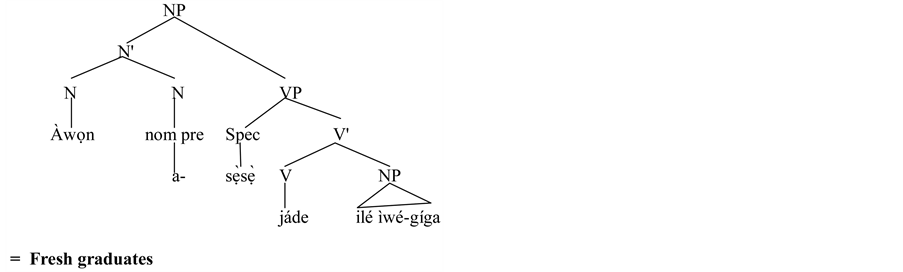

(2) Àwọn-àsẹ̀sẹ̀-jáde-ilé-ìwé-gíga Fresh graduates

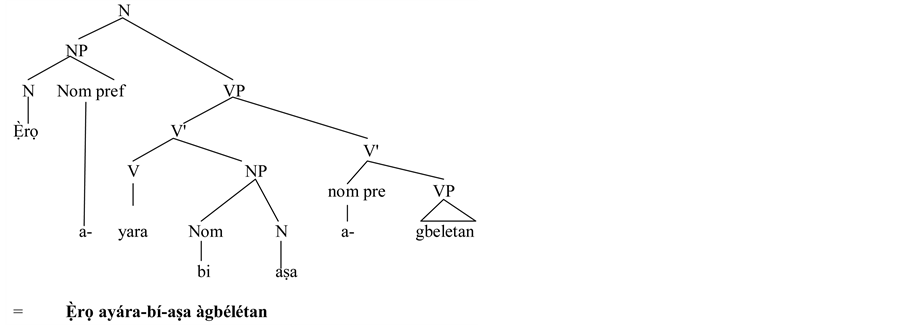

(3) Ẹ̀rọ-ayára-bí-àṣá-àgbélétan Laptop

(4) Ìlànà-tepo-níye-ó-pé-ọ Downstream deregulation

(5) Bọ́ọ̀lù-wòmí-n-gbá-sí-ọ Penalty kick

We have taken these five coinages as representatives of the others. In the first word, we have the Noun with its modifier and then the clausal modifier for the noun. The analysis is as follows:

Òdo (zero) Noun

méjì (two) nominal modifier

togbe ẹẹjọ sáàrin clausal modifier for the noun head

We can represent the analysis above on a tree diagram below.

Example (2) above is slightly different from (1) in that what we have as the subject is a bare noun in form of a pronoun Àwọn representing the corp members. The only modifier in the coinage is àsẹ̀sẹ̀ “newly” this word is a verbal nominal modifying the noun, Àwọn. Another novel thing we could observe in this coinage is that despite the fact that jáde is an intransitive verb, it is used transitively in this coinage. We give the derivational analysis of the word.

Àwọn (they) Noun (Pronominal)

àsẹ̀sẹ̀ (verbal noun) Newly

jáde Come out (just complete)

ilé-ìwé-gígá University

For better understanding of the derivation of this coinage word, we give the tree diagram below for its analysis.

The third data (3) above also has a different strategy in deriving it. While the first two derivations (1, 2) have just about two verbs within them, the third coinage has multi-verbs within it. By this, we mean that it has more than two verbs. Another significant difference between (1) on the one hand and the other examples in the above data (i.e. 1 - 5) is that while (1) has an IP within it, the others do not have an IP within them. The analysis below together with its tree diagram elucidates the occurrence of these multi-verbs.

Ẹ̀rọ (N) Machine

a- (pref) Nom prefix

yara (verb) quick

bi (Nom) nominalizer

àṣá (N) eagle

a- (pref) Nom prefix

gbe (verb) carry

le (verb) on

itan (N) Tigh

The three analyses given above serve as motif for the other coinages whose analyses are not done here. However, all the other derivations are capable of fitting into the diagnostic frame which the analysed examples represent. We will discuss the morphology of the one-word coinage in the section following.

4. Morphological analysis

As shown in Data “B” above, it can easily be observed that the majority of the coinages shown in the data fall under what can be called complex words. Morphologically complex words are in two parts. They are reduplicated words and compound words. Our major focus in this section will be on the compound words.

Compound words can be nominal compound or verbal compound. Nominal compound words are those to which the nominal prefix is attached to the noun. That is, the first morpheme immediately following the prefix is always a noun; while the verbal compound words are those to which the nominal prefix is attached to the verb. This is to say that the verb is the immediately following word that comes after the nominal prefix.

Yorùbá nominal or verbal compound words may or may not have head. However, whether there is head or not, there is always a rule strictly followed when such words are being derived. There are three groups to which compound words can belong. This is not peculiar to Yorùbá alone; it is a phenomenon general to most languages of the word. Therefore compounds words in languages, Yorùbá inclusive can fall into any of the following that have been identified.

► endocentric compounds

► exocentric compounds

► co-ordinate compounds

Endocentric compounds are those whose heads are within them while exocentric compounds have their heads outside the words. Taiwo (2009: p. 41) notes that compounds which are derived through desententialization in Yorùbá are exocentric while he (Taiwo, 2009) opines that many of the compound words in Yorùbá are endocentric. Taiwo (2009) further asserts that verbal compounds in Yorùbá can either be endocentric or co-ordinate compounds (cf. Taiwo, 2006).

In line with our explanation so far, we shall make use of some of our data in Data “B” for our morphological analysis. In the example below some of which are nominal compounds while some are verbal compounds, the nominal prefix heads the compound.

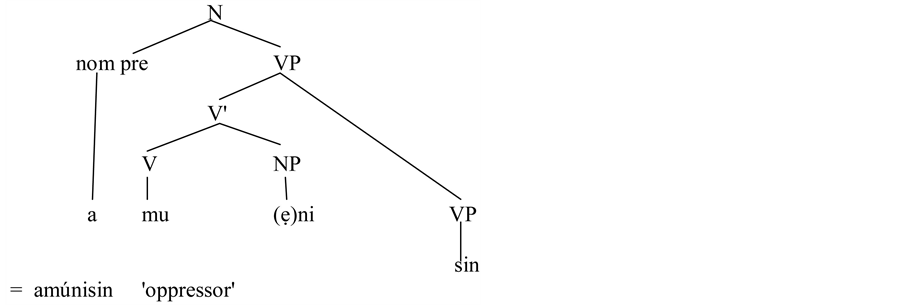

1) a- + mu + ni + sin < amúnisìn “oppressor”

take person serve

2) i- + dana + sun + ile < ìdánásunlé “arson”

make burn house

3) a- + dun + koko + mọ + ni < adúnkokómọ́ni “terrorist”

shout wolf to one

4) a- + lu + pupu < alùpùpù “motocycle”

sound

5) oni- + igba + meji < onígbáméjì “Cholera”

owner calabash two

In the first four examples, we have the nominal prefix being attached to the verb which immediately follows it. This preverbal nominal prefix turns the whole word into a nominal. This shows that the prefix is the head of the compound. Issues like this separates Yorùbá from English. While English is a Right Hand Head Rule (RHHR) Yorùbá is a Left Hand Head Rule (LHHR) in its morphological analysis. To talk of RHHR or LHHR is to say that morphologically complex words have heads. This issue of headedness has been discussed variously in the literature (see Williams, 1981; Selkirk, 1982; Owolabi, 1985; Fabb, 2001; Ogunkeye, 2002 and some other scholars). Right hand or left hand head rule is to say that the head of a morphologically complex word is to the right or to the left of that word.

We shall draw a tree diagram to represent the morphological analysis of each of the data above.

The diagram above shows the phenomenon of LHHR prevalent in the Yorùbá morphology. The morpheme “a” which nominalises the VP to make it a noun is the head. Looking at the other data, it will be observed that the head of each phrase can be found at the initial position of the phrases.

5. Conclusions

This paper has discussed language engineering; a recently introduced field of linguistics where words are formed and coined to cater for the names for the new technological inventions. The paper has zeroed in on the electronic media for its source of data. We have explained the strategy by which the words used as our data are coined.

In the paper, we noted the contributions of the electronic media people in the development of Yorùbá language and in the dissemination of information to the public. It also paves the in making efforts to give metalanguage to the various concepts that are new in the society as a result of technological advancement. The paper therefore concludes that the academia should also endeavour to work hand in hand with the media in the formation of new words for the concepts being introduced to the society.

References

- Akanbi, T. A. (2011). Yorùbá in Diachronic Perspective: A Case of Language Change. In African Perspectives: Contemporary Discourse in Language and Literature, Kenya: Pen-Point Writers’ Forum, Egerton University.

- Akanbi, T. A. (2012). Insight into Language Engineering: A Preliminary Note. In The Analysts’ Voice (pp. 5-8). A publication of National Association of Linguistics and Languages Students, Ekiti State University, Ado-Ekiti Branch.

- Awobuluyi, O. (1994). Yorùbá Metalanguage Vol. II. Ibadan: University Press Ltd.

- Bamgbose, A. (1986). Yorùbá: A Language in Transition. Lagos: J. F. Ọdúnjọ Memorial Lecture Series No. 1.

- Bamgbose, A. (1992). Yorùbá Metalanguage Vol. I. Ibadan: University Press Ltd.

- Capo, H. B. C. (1990). Comparative Linguistics and Language Engineering in Africa. In E. N. Emenajo (Ed.), Multilingualism, Minority Languages and Language Policy in Nigeria (pp. 1-9). Agbor: Central Books Ltd/LAN.

- Fabb, N. (2001). Compounding. In A. Spencer, & A. Zwicky (Eds.), The Handbook of Morphology. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers Ltd.

- Ogunkeye, O. (2002). A Lexicalist Approach to the Study of Aspects of Yorùbá Morphology. Unpublished Ph.D. Thesis, Ibadan: University of Ibadan.

- Opeyemi, A. M. (2013). Effects of Indigenous Language Electronic Media on the Society: A Case Study of Orisun FM, Ilé-Ifẹ̀ (A Long Essay). Ado-Ekiti: Ekiti State University,

- Owolabi, K. (1995). More on Yorùbá Prefixing Morphology. In K. Owolabi (Ed.), Language in Nigeria: Essays in Honour of Ayọ Bamgboṣe (pp. 92-112). Ibadan: Group Publishers.

- Owolabi, K. (2006). Nigeria’s Native Language Modernization in Specialized Domains for National Development: A Linguistic Approach. Inaugural Lecture, University of Ibadan, Ibadan: Universal Akada Books (Nig.) Ltd.

- Selkirk, E. (1982). The Syntax of Words. In Linguistic Inquiry Monograph Seven. Cambridge: MIT Press.

- Taiwo, O. (2006). Mọfọlọji (Morphology). Ibadan: Lay of Publishing Service.

- Taiwo, O. (2009). Headedness and the Structure of Yorùbá Compound Words. Taiwan Journal of Linguistics, 7, 27-52.

- Williams, E. (1981). On the Notions of Lexically Related and Head of a Word. Linguistic Inquiry, 12, 245-274.

- Yusuff, L. A. (2008). Lexical Morphology in Yorùbá Language Engineering. An Unpublished Ph.D. Thesis Submitted to the Department of Linguistics, African and Asian Studies. Lagos: University of Lagos.

NOTES

1Yorùbá Studies Association is on the verge of completing another volume of Yorùbá metalanguage. It is believed that this work will be published not far from now.

2Most of the data used in this paper are those taken from Opeyemi, 2013.