Open Journal of Business and Management

Vol.2 No.3(2014), Article ID:48145,19 pages

DOI:10.4236/ojbm.2014.23029

An Overview of the Design School of Strategic Management (Strategy Formulation as a Process of Conception)

Alfred Sarbah1, Doris Otu-Nyarko2

1School of Management & Economics, University of Electronic Science & Technology (UESTC) of China, Chengdu, China

2Faculty of Business & Management Studies, Kumasi Polytechnic, Kumasi, Ghana

Email: sarbah@yahoo.com, dotunyarko@yahoo.com

Copyright © 2014 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

![]()

![]()

Received 20 May 2014; revised 21 June 2014; accepted 10 July 2014

ABSTRACT

Since its emergence in the 1960’s, the field of strategic management and strategy formulation has evolved into a complex area of study, even for the most knowledgeable and experienced strategist. Strategy Safari (FT Prentice Hall, 2002), subtitled “A Guided Tour through the Wilds of Strategic Management” by Henry Mintzberg, Bruce Ahlstrand and Joseph Lampel is an overview of the full field of academic and business studies of strategy formulation, based on previous lecture series delivered by Mintzberg. In that book, the authors identified ten (10) schools of strategy formulation. One of which is the design school. The “design school” of strategic management, which focuses on a non-complex model that perceives the process of strategic formation as a design process to reach a satisfactory balance between internal distinctive competence and external threat and opportunity. Strategy formation should be a conscious, informal and controlled process of thought. While the model has limitations, four conditions may encourage an organization to use the design school model, including when relevant knowledge has been established and a situation is stable; an organization can cope with a centrally articulated strategy; and one person can handle all data connected to developing strategy. There are several criticisms of the design school of thought on its reliability and validity. The authors have counteracted with these criticisms and explained that it is based on assumptions which are misleading, as the concept propagated by design school was over simplified and restricted in application.

Keywords:Design School, Strategy, Strategy Formulation

1. Introduction

Throughout time, a large amount of thinkers has addressed the issues related to business strategy systems from many different angles. To a large extent, the difference in perspective can be understood from a wide range of base disciplines on which the strategy arguments are based, for example economics, biology, anthropology, philosophy and politicology.

Nowadays, most business enterprises are engaged in strategic planning by using new ideas, objects, practices and reaching the goals. Generally, strategy is a simple way to analyze the current situation of the organization, expected future situation, the right direction confidently and achieving the objects of the organization. Actually, it is more than that which provides the systematic way for identifying and evaluating factors external to the firm and fixing them with the organization’s abilities. In addition, strategy is a long process over long time periods with individual resources within a competitive environment to meet customer needs. In other words, strategy is a method or process of direction and a scope of an organization to achieve opportunities with its pattern of resources and meet the demand of markets and stakeholder expectations. A company’s strategy can decide the fate of an organization, help them to create innovative products and sustain their competitive advantage.

Though there is no single universal definition of strategy, it may however be defined as “the pattern or plan that integrates an organizations major goals, policies, and action sequences into a cohesive whole.” A well formulated strategy helps to marshal and allocate an organization’s resources into a unique and viable posture based on its relative internal competencies and shortcomings, anticipated changes in the environment, and contingent moves by intelligent opponents. Mainly Strategies are shaped and designed for the whole organization by senior managers, therefore administering strategy should start from the top to bottom. Effective strategies involve discussion and communication. Strategic management focuses on integrating managerial abilities and techniques such as marketing, financial/accounting, human resource management, production management, research development to achieve organizational success [1] . Organizations should be able to sustain competitive advantage in a discrete and identifiable market. It is the way a company creates value through the configuration and coordination of its multimarket activities. When all these are carefully managed then the organization is able to achieve its competitive or corporate advantage. Strategy formulation is therefore the process of identifying or deciding what to do with a combination of different factors.

The literature that can be subsumed under “strategy formation” is vast, diverse and, since 1980, has been growing at an astonishing rate. There has been a general tendency to date it back to the mid-1960s, although some important publications precede that date, such as Newman’s initial piece “to show the nature and importance of strategy” in the 1951 edition of his textbook Administrative Action [2] . Of course the literature on military strategy goes back much further, in the case of Sun Tzu probably to the fourth century BC as indicated by Griffith in Sun Tzu [3] . A good deal of this literature naturally divides itself into distinct schools of thought.

There are numerous ways of studying strategic management; some of them are more pedagogic than others. One method is to classify strategic management into schools of thought and this is in terms of teaching and learning an ingenious method. Mintzberg et al. [4] propose a total of 10 schools of thought, these been categorized into two: Firstly prescriptive schools which were especially in vogue in the 70s and 80s and to some extent are still very much loved by companies today. Secondly, descriptive schools, most of which have been discovered over the last 20 years.

Mintzberg emphasizes this broad diversity of perspectives in the current debate and has identified ten main distinct schools in strategic thinking [5] . Three of these schools—Design, Planning and Positioning School—fall under the prescriptive school and the other seven schools—Entrepreneurial, Cognitive, Learning, Political, Cultural and Environmental School—are descriptive in nature. As with any classification, there is a certain danger in the sense that trying to put rich individual ideas and concepts into a limited number of “boxes” which may lead to oversimplification. However, this classification of strategy schools does contribute to a deeper understanding of how strategy, systems are perceived in a limited number of the mainstreams of thinking. Ten deeply embedded, though narrow, concepts typically dominate current thinking on strategy.

Among the schools of thought on strategy formation, one in particular underlies almost all prescriptions in the field. Referred to as the “design school”, it proposes a simple model that views the process as one of design to achieve an essential fit between external threat and opportunity and internal distinctive competence. The design school therefore proposes a model of strategy making that seeks to attain a match, or fit, between internal capabilities and external possibilities. In the words of this school’s best-known proponents, “Economic strategy will be seen as the match between qualifications and opportunity that positions a firm in its environment”. Design School has an important and influential contribution in developing other schools of thoughts and providing a foundation to strategic management principles.

2. Origins of the School

The design school has been very influential in the development of business strategy and can be seen as the forerunner of the positioning school. The real impetus for the design school came from the General Management group at the Harvard Business School, beginning especially with the publication of its basic textbook, Business Policy: Text and Cases [6] , which first appeared in 1965. Philip Selznick’s [7] in particular, introduced the notion of “distinctive competence”, discussed the need to bring together the organization’s “internal state” with its “external expectations”, and argued for building “policy into the organization’s social structure”, which later came to be called “implementation”. Chandler [8] , in turn, established this school’s notion of business strategy and its relationship to structure.

The school therefore originated with the publication of Philip Selznick’s “Leadership in Administration” in 1957 and Alfred D. Chandler’s “Strategy and Structure” in 1962. Philip Selznick was the first to articulate the basic concept that undergirds this model and wrote in his book [9] that:

“Leadership sets goals, but in doing so takes account of the conditions that have already determined what the organization can do and to the extent that it must do. In defining the mission of the organization, leaders must take into account:

1) The internal state of the policy: the strivings, inhibitions and competences that exist within the organization, and 2) The external expectations that determine what must be sought or achieve if the institute is to survive.

But the real impetus for the design school came from the General Management group at the Harvard Business School, beginning especially with the publication of its basic textbook, Business Policy: Text and Cases, which first appeared in 1965.

From the mid-sixties the school was highly influential in the Harvard Business School. Kenneth Andrews of Harvard Business School has been given credit as a primary architect of the “Design” school of strategic management, along with Chandler and Ansoff [10] . They emphasize the leader’s role, under the design school, as that of the primary planner of the medium to long-term development of the organization. This “design school planner” leader, designs strategic developments by formulating a strategy in a controlled and conscious process of thought. He/she is the leader who creates success by asking and answering the questions of “Where are we now?” “Where do we want to be?” and “How are we going to get there?” In a process of systematic business planning. The “design planner”, therefore, is an expert at anticipating, with the help of strategic planning’s analytical techniques, what future business environments are to be like, and at devising appropriate product-market strategies which fit productively (economically speaking) with the environmental opportunities and threats facing the organization and its resource strengths and weaknesses.

According to the design school, therefore, strategy, systems are prescribed to be deliberate in nature and strategy formation is regarded as a process of conscious thought. Responsibility for that control and consciousness must rest with the chief executive officer, who is thereby the main strategist. Moreover, the model of strategy formation should be kept as simple and informal as possible. Strategies should be one of a kind, where the best ones result from a process of individualized design. The strategy, systems thus should be regarded as a true design process, which is complete when strategies appear fully formulated. Thereby strategies should be made explicit and they have to be kept simple. Finally, only after these unique, full blown, explicit, and simple strategies are fully formulated can they be implemented.

The design school therefore represents, without question, the most influential view of the strategy-formation process. At its simplest, the design school proposes a model of strategy making that seeks to attain a match, or fit, between internal capabilities and external possibilities. In the words of this school’s best-known proponents, “Economic strategy will be seen as the match between qualifications and opportunity that positions a firm in its environment” [11] .

3. The Design School Model

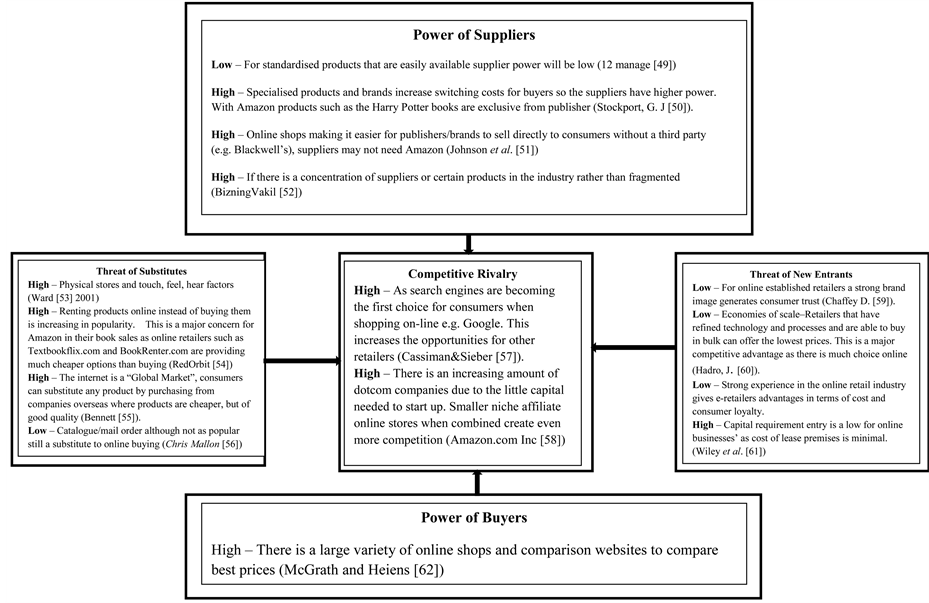

Henry Mintzberg taught that “strategy formulation is judgmental designing, intuitive visioning, and emergent learning; it is about transformation as well as perpetuation; it has to include analyzing before and programming after as well as negotiating during.” In 1998, Mintzberg outlined activities, aligned with figure below, that need to be carried out by upper management:

1) Conducting an internal appraisal to understand the organization’s competencies, strengths, and weakness;

2) Conducting an external appraisal of the environment to determine threats and opportunities.

At its simplest, the design school proposes a model of strategy making that seeks to attain a match, or fit, between internal capabilities and external possibilities. The model places primary emphasis on the appraisals of the external and internal situations, the former uncovering threats and opportunities in the environment, the latter revealing strengths and weaknesses of the organizations (aka SWOT analysis).

The model places primary emphasis on the appraisals of the external and internal situations, the former uncovering threats and opportunities in the environment, the latter revealing strengths and weaknesses of the organization (Figure 1).

On external appraisal, the technological, economic, social, and political aspects of a company’s environment are important and a brief consideration of the issues of forecasting and scanning. While on internal appraisal, commitments to ways of acting and responding are built into the organization are crucial. Two other factors are believed to play major role in strategy making. One is managerial values—the beliefs and preferences of those who formally lead the organization, and the other is social responsibilities—specifically the ethics of the society in which the organization functions, at least as these are perceived by its managers.

The figure below shows the model and the other two other factors believed to be important in strategy making. These as discussed above are the managerial values-the belief and preferences of those who formally lead the organization, and the other is social responsibilities-specifically the ethics of the society in which the organization function, at least as these are perceived by its managers. Once alternative strategies have been determined, the next step in the model is to evaluate them and choose the best one. Finally, virtually all of the writings of this school make a clear that once a strategy has been agreed upon, it is then implemented.

The design school is one of the ten strategic management schools of thought that was coined by Mintzberg et al. The design school views strategy formulation as a process of conception where the central challenge is to establish a fit between the firm’s qualities and the opportunities present in the environment.

The design school endorses a prescriptive view of strategy formulation, being potentially more concerned with how strategy should be formulated rather than how it actually is. This school therefore seeks to find a match or fit for internal capabilities and external possibilities. It says to think before you leap. It lays a lot of importance in the analysis of external and internal situations. The “design” school is responsible for the development of the Strength, Weaknesses Opportunities Threats (SWOT) model. In this model, the strengths and weaknesses of a company are mapped, together with the opportunities and threats in the marketplace.

The data can be used to analyze various strategic options, which both exploit the internal opportunities and anticipate the market situation. Reaching a good fit between the internal opportunities (strengths and weaknesses) and the external circumstances (opportunities and threats) can be considered to be the central guideline of this school of thought. A key role in the strategy formation is played by the board of directors, and in particular by the chairperson. External covers the threats and opportunities and the internal covers the strengths and weaknesses. Basically, it is a SWOT analysis. Social responsibility and Managerial values also play a role in the formulation of the strategy. Once the alternatives are figured out, the best of them are chosen. Once a strategy is chosen, it is then implemented.

This approach can be further formalized into a more systematic approach. In this perspective, strategy formation consists of developing, formalizing and implementing an explicit plan. The well-known SWOT analysis is therefore one of the main central tools of the design school. The strategy of an organization is designed through the analysis of its internal strengths and weaknesses that define the firm’s distinctive. The evaluation of external opportunities and threats help to define the key success factors. These are combined to allow for the creation of strategy, or at least the definition of a number of strategic alternatives.

The resulting strategy alternatives are evaluated and refined using the firm’s managerial values—the beliefs and preferences of the organization’s leaders-and social responsibility—the ethics of the social environment as perceived by the managers.

Richard Rumelt [12] suggests that the strategy must be evaluated once it has been selected from multiple options. This evaluation should be based upon following tests which are considered to be the best evaluation framework:

Ÿ Consistency: The strategy must not present mutually inconsistent goals and policies.

Ÿ Consonance: The strategy must represent an adaptive response to the external environment and to the critical changes occurring within it.

Ÿ Advantage: The strategy must provide for the creation and/or maintenance of a competitive advantage in the selected area of activity.

Ÿ Feasibility: The strategy must neither overtax available resources, nor create unsolvable sub problems.

Once the best possible strategy has been selected, implementation follows.

3.1. Premises of the Design School

Running through most of the literature that was identified with this school are a number of fundamental premises about the process of strategy formulation. A number of basic premises underlie the design school, some fully evident, others only implicitly recognized. These premises include external environmental variables and factors of strength and weaknesses as their variables. These premises are as follows:

1) Strategy formation should be a deliberate process of conscious thought. Action must flow from reason: effective strategies derive from a tightly controlled process of human thinking. Strategy making in this sense is an acquired, not a natural, skill or an intuitive one—it must be learned formally.

2) Responsibility for that control and consciousness must rest with the chief executive officer: that person is the strategist, the manager who sits at the apex of the organizational pyramid. It might be noted that this premise not only relegates other members of the organization to subordinate roles in strategy formation, but also precludes external actors from the process altogether (except for members of the board of directors, who Andrews believed must review strategy).

3) The model of strategy formation must be kept simple and informal. Fundamental to this view is the belief that elaboration and formalization will sap the model of its essence. This premise, in fact, goes with the last: one way to ensure that strategy is controlled in one mind is to keep the process simple. This distinguishes the design school from the entrepreneurial school on one side and the planning and especially positioning schools on the other.

4) Strategies should be one of a kind: the best ones result from a process of individualized design. As suggested above, it is the specific situation that matters, not any system of general variables. It follows therefore, that strategies have to be tailored to the individual case. And that process above all should be a “creative act”, to build on distinctive competence.

5) The design process is complete when strategies appear fully formulated as perspective. This school offers little room for instrumentalist views or emergent strategies, which allow “formulation” to continue during and after “implementation”. The big picture must appear—the grand strategy, an overall concept of the business.

6) These strategies should be explicit, so they have to be kept simple. Andrews, in common with virtually all the writers of this school, believed that strategies should be explicit for those who make them, and, if at all possible, articulated so that others in the organization. “Simplicity is the essence of good art”.

7) Finally, only after these unique, full-blown, explicit, and simple strategies are fully formulated can they then be implemented. Central to this distinction is the associated premise that structure must follow strategy. It appears to be assumed that each time a new strategy is formulated, the state of structure and everything else in the organization must be considered a new.

3.2. Critique of the Design School

The writings of the design school can be critiqued on a number of levels. In perhaps the most general sense, the school has denied itself the chance to adapt. Research results that have put parts of it under suspicion were not considered; indeed, there was no reason to, if the model could not be elaborated upon.

A strategy that locates an organization in a niche can narrow its own perspective. This seems to have happened to the design school itself (not to mention all the other schools) with regard to strategy formation. The premises of the model deny certain important aspects of strategy formation, including incremental development and emergent strategy, the influence of existing structures on strategy, and the full participation of actors other than the chief executive.

The important criticism is about:

Ÿ How does an organization know its strengths and weaknesses? On this, the design school has been quite clear—by consideration, assessment, judgment supported by analysis; in other words, by conscious thought expressed verbally and on paper. One gets the image of executives sitting around a table, discussing the strengths, weaknesses, and distinctive competencies of an organization, much as do students in a case study class. Having decided what these are, they are then ready to design strategies.

Ÿ But are competences distinct even to an organization? Might they not also be distinct to context, to time, even with the application? In other words, can any organization really be sure of its strengths before it tests them?

The criticism is dealt by the following steps:

Assessment of Strength and Weaknesses: By Passing Learning: The question of how a firm is going to determine its strength and weaknesses is addressed by simply analyzing the firm’s present position. This analysis requires judgmental behavior. Every strategic change involves some new experience, a step into the unknown, the taking of any kind of risk. Therefore, no organization can ever be sure in advance whether an established competence will prove to be a strength or a weakness.

Structure Follows the Strategy: As the Left Foot Follows the Right Foot: The past counts, just as does the environment, and organization structure is a significant part of that past. Claiming that strategy must take precedence over structure amounts to claiming that strategy must take precedence over the established capabilities of the organization, which are embedded in its structure. The structure may be somewhat malleable, but it cannot be altered at will just because a leader has conceived a new strategy. Many organizations have come to grief over just such a belief.

Making Strategy Explicit: Promoting Inflexibility: Once the strategies have been created, then the model calls for their articulation. Failure to do so is considered evidence of fuzzy thinking, or else of a political motive. But there are others, often more important, reasons not to articulate strategy, which strike at the basic assumptions of the design school. Explicit strategies are blinders designed to focus direction and so to block out peripheral vision. They can thus impede strategic change when it does become necessary. Put differently, while strategists may be sure for now, they can never be sure forever. The more clearly articulated the strategy, the more deeply embedded it becomes in the habits of the organization as well as in the mind of its strategists.

Separation of Formation from Implementation: Detaching Thinking from Acting: The formulation-implementation dichotomy is central to the design school—whether taken as a tight model or a loose framework.

In summary, the criticism leveled on the design school was bulleted below:

§ No clarity in the organization in terms of its strengths and weaknesses.

§ When, how and when not should be the strategies formulated were not well defined.

§ The major assumption is that the data can be aggregated and transmitted to the upper levels without substantial losses.

§ The environment can always be understood and is sufficiently stable in the future.

§ How does an organization know its strengths and weaknesses? Can organizations, be sure of its strengths before it tests them? The discovery of “what business are we in” cannot be undertaken merely on paper. More often than not, strengths turn out to be far narrower than expected, and weaknesses far broader.

§ Certainly strategies must often be made explicit, for purposes of investigation, coordination and support. The questions are when? And how? And when not? How? And when not?

§ The major assumption is that the data can be aggregated and transmitted up the hierarchy without any significant loss or distortion. This assumption often fails, destroying carefully formulated strategies in the process.

§ The other significant assumption in the design school is that environments can always be understood, currently and for a period well into the future and that the environment itself is sufficiently stable or at least predictable. There is, however, no one best route to truth in strategy, indeed no route at all.

§ Strategy must be formulated in full before implementation.

§ Once implementation takes place, there is no space for changing the strategy.

§ Learning plays no part in this approach.

§ It places an organization quite firmly into a market niche, limiting its potential to break into new markets.

§ The approach is too rigid and does not allow flexibility.

In spite of such criticism, the design school has been a dominant architect of contemporary strategy management. Its focus on simplicity and on a centralized (unilateral) decision-making process has helped many firms to strengthen their market position. However, this―easy to do and implement recipe requires of certain conditions to succeed: the person (―brain) taking the role of strategist, should be able to handle efficiently all needed information. Only then, she or he becomes capable to understand and manage the situation in detail. This implies that the required knowledge should be in place before the strategy is implemented. However, to be implemented successfully, a strategy that is centrally conceived must be adopted and supported by the entire organization. In general, Mintzberg suggests that this type of strategy process (formulation plus implementation) fits better organizations amid a period of turmoil and one of operating stability.

3.3. Strengths and Weaknesses

The centerpiece in the Strategic Toolkit is the SWOT. This remains popular in textbooks and amongst consultants in spite of new strategic techniques. The SWOT with the design school model is a convenient tool allowing a consultant drop into an organization, do a SWOT analysis, compile a strategy and move on. But:

Ÿ Listing strengths on paper is prone to bias and over-confidence and is very different from testing the organization and experiencing the strengths at work. Research and popular press alike show that listed strengths are of uncertain value.

Ÿ Experience shows that strengths are narrower than expected and weaknesses broader.

Ÿ The business we are in cannot be discovered in a paper exercise but requires testing and experience.

Ÿ SWOT information is usually not used in strategy formulation.

Ÿ Business literature is full of references to events where assumed strengths either did not materialize or where they did but turned out to be hindrances.

4. Application of Design School of Thought

The design school model would seem to apply best at the junction of a major shift for an organization, coming out of a period of changing circumstances and into one of stability. Of course, a clever new management might also wish to impose a better strategy for an organization whose circumstances have not changed.

There is another context where the design school model might apply, and that is the new organization, since it must have a clear sense of direction in order to compete with its more established rivals (or else position itself in a niche free of their direct influence). This period of the initial conception of strategy is, of course, often the consequence of an entrepreneur with a vision, the person who created the organization in the first place. The design school’s major contribution is that it has developed an important vocabulary by which to discuss grand strategy and has provided the central notion that strategy represents a fundamental fit between external opportunity and internal capability; an “informing idea”.

5. A Look at the Operations of Amazon.com

Amazon.com was one of the first major companies to sell goods over the Internet and has become a worldwide established name. Amazon.com is an American e-commerce company that is based in Washington. It was founded by Jeff Bezos in 1994 and began as an online bookstore, but due to its success, Amazon has diversified into other product lines and services such as groceries, electronics and Merchant Progra. Amazon is the 5th most admired company in the world. Amazon has embraced what known as a “design school model” of strategy development.

Amazon.com’s stock price has fluctuated in over the years from $105 in 1999 to $5 in 2001 [13] . Amazon.com has developed separate websites for Canada, UK, Germany, France, China and Japan. Amazon.com vision is to become: “Earth’s biggest selection and to be Earth’s most customer centric company.” [14]

Amazon is one company that has adopted and implemented or made use of the design school approach to strategy formulation. It conducted an internal appraisal of itself, and an external appraisal of threats and opportunities.

5.1. Amazon.com’s Internal Appraisal Approach

The design school model calls for both external and internal appraisals. An external appraisal helps an organization to understand threats and opportunities that are out there in the market. The internal assessment helps the organization to understand its strengths and weaknesses. The “Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats” (SWOT) tool is one that most familiar analysis tool and stems from the design school model.

Internal analysis provides a useful method to establish the relationship between Amazon.com’s resources and capabilities (internal strengths), and how this is used to create value for the customer. The internal analysis can also help to identify the limitations within Amazon.com’s operations [15] . Knowing, building, and fully leveraging strengths in the best manner possible is an important key to creating long-term competitive advantage. Amazon is a great, leading-edge company that has successfully developed and implemented compelling strategies. Amazon embraced the “design school model” of strategy development. Despite the title, the model is simple to understand and can be highly effective. It is the one used most by professors and consulting organizations. The diagram in Figure 1 above is Henry Mintzberg’s illustration of the model.

There are three simple tools that Amazon focuses on as part of its internal appraisal process. They include: (a) Value Chain; (b) Resources Based View; (c) Financial Analysis.

5.1.1. Value Chain

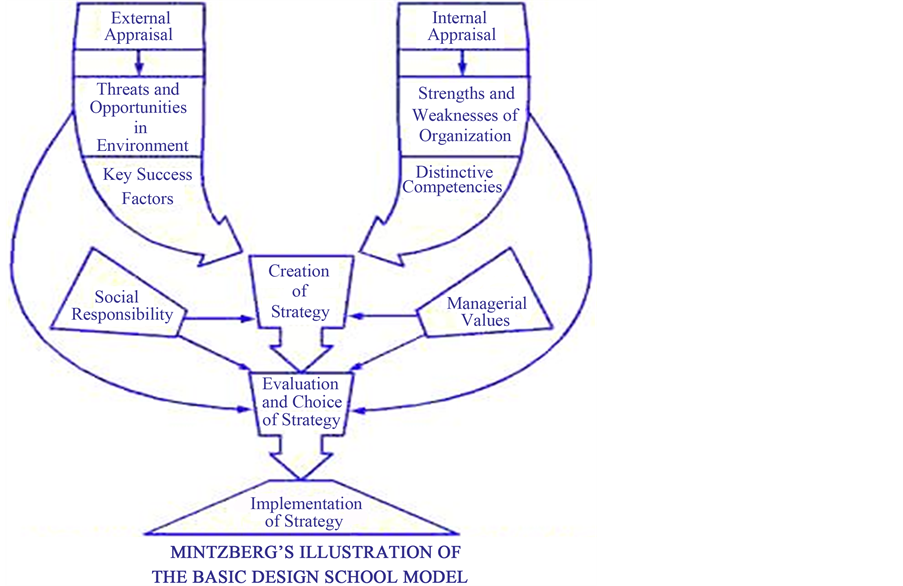

Amazon developed a value chain of itself to its internal environment so that it can operationally best add value and maintain a competitive advantage. They used the value chain model from Michael Porter’s book, “Competitive Advantage: Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance.” The value chain analysis undertaken examines the operational effectiveness of activities that enable Amazon.com to perform better than its competitors; i.e. the distinctive value chain activities that are difficult to imitate. Using the framework proposed by Amit and Zott [16] , this analysis focuses on “value creation” and “transaction cost economies”; where Amazon.com configures its value chain activities to create unique value for customers, reduce its costs of carrying out these activities and reduce the cost of its customers’ transactions. The figure below indicates examples of how Amazon.com has created value and reduced costs in its value chain activities.

Amazon developed a value chain of itself so internally it can operationally best add value and maintain a competitive advantage. They used the value chain model from Michael Porter’s book, “Competitive Advantage: Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance.” [17] This is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 1. The basic design school model.

Figure 2. Amazon.com value chain.

5.1.2. Resource Based View

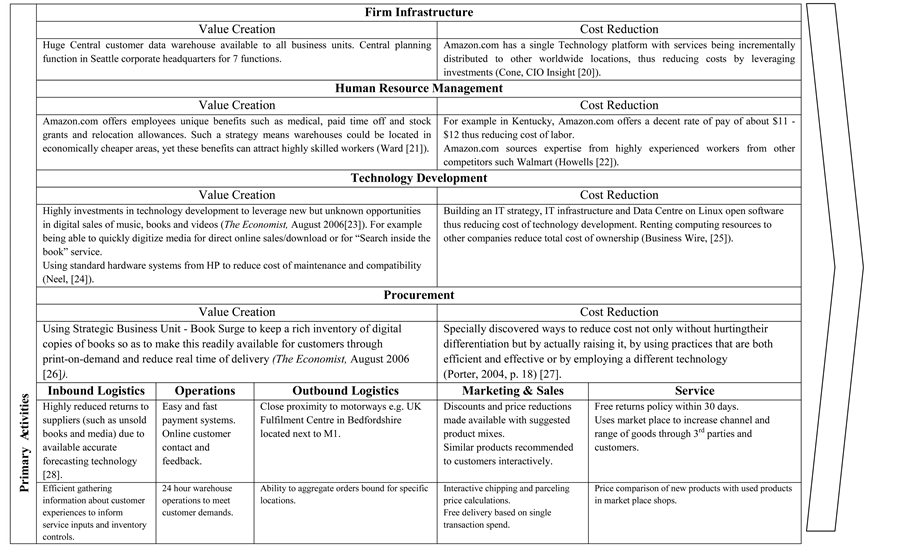

The resource based view of a firm suggests that the sustainable competitive advantage and superior performance of an organization are determined by its distinct capabilities, i.e. resources and competences [18] . The resource based view helps an organization to determine where to invest in critical resources to have a competitive advantage. The more valuable and rare the right resources are in the right places, the more likely the firm may have a long-term advantage over its competition.

Therefore, in order for Amazon.com to develop, implement and sustain effective strategies, the capabilities of the organization need to be exploited [19] . The resource based view, therefore helps an organization to determine where to invest in critical resources to have a competitive advantage. The more valuable and rare the right resources are in the right places, the more likely the firm may have a long-term advantage over its competition. Amazon.com’s resources and competencies have been highlighted in Figure 3.

A firm utilizes its resources and capabilities to create a competitive advantage. The organization’s resources and capabilities combined together constitute its distinctive competencies. There are two types of competitive advantage:

Ÿ Cost Advantage: A cost advantage exists when a company is able to deliver the same benefits as their competitors but at a lower price.

Ÿ Differentiation Advantage: A differentiation advantage exists when a firm is able to deliver benefits that surpass their competitors.

Amazon successfully identified the right resources and developed its capabilities in key target areas. These investments resulted in:

Ÿ Sophisticated online retailing technologies;

Ÿ Personalization features for customers on its websites;

Ÿ Reliable and easily scalable IT systems all one platform;

Ÿ New products (100 different products in seven major geographic markets);

Ÿ Top customer relationship system;

Ÿ State of the art warehousing.

5.1.3. Financial Analysis

Amazon reviews at the macro-level:

Figure 3. Resource based view. Source: Authors construct.

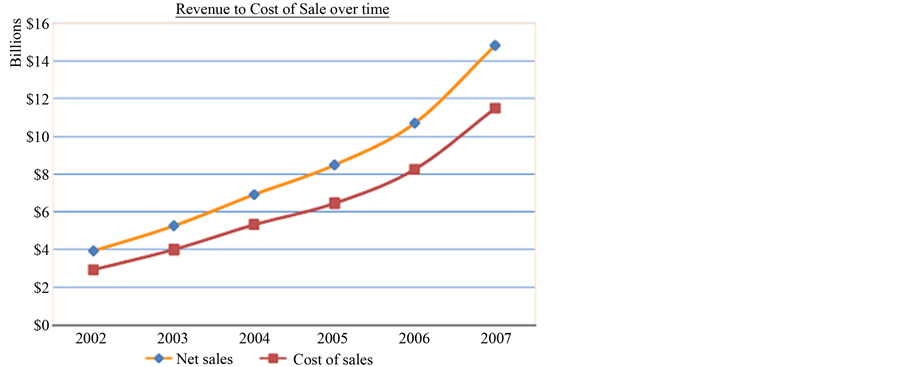

Ÿ Revenue to cost of sales overtime;

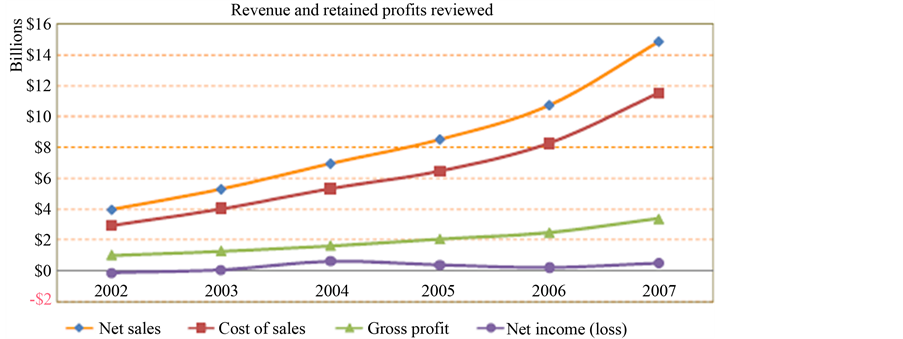

Ÿ Revenue and retained profits;

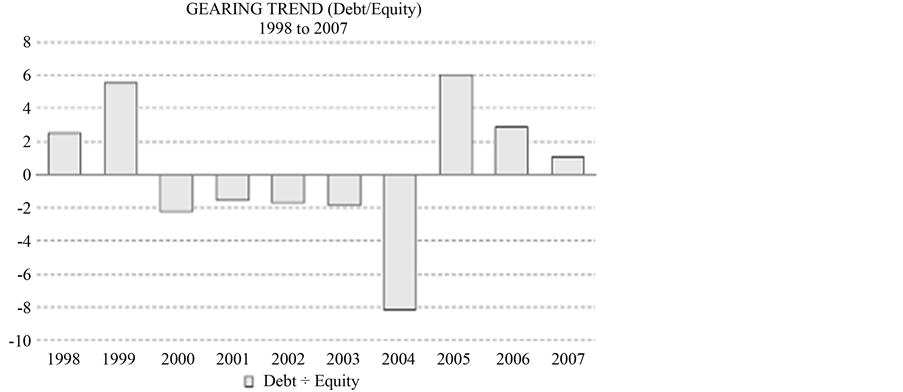

Ÿ Gearing, debt and capital structure.

Amazon’s investments are paying off. Their net sales continue to grow, their cost of goods decreases as a % of sales and their net income continues to increase. And, they continue to invest in initiatives that provide them a longer-term competitive advantage.

The graph above, Figure 4 shows that net sales have been increasing year on year since 2002. In 2007, we can see that the gap between net sales and cost of sales was the biggest it had ever been. This indicates that operations and the costs of generating revenue have been managed efficiently.

However, despite the year on year increase in sales revenue, the net income (Figure 5) trend shows that since 2004, reported profit (net income) decreased. Possible reasons for this trend are discussed below.

5.1.4. 2004-2006, Drop in Net Income Analyzed

During the 2005-2006 period, the company’s decision to increase investment in technology and marketing with an extra $662 million as well as increasing the marketing budget by an extra $65 million would have contributed to the extended down turn of profits. Table 1 shows a net profit margin decreasing from 8.5% in 2004 to a very low 1.4% within the space of 2 years. Such was the case until 2007 when the upward trend emerged once again; an indication that some form of recovery is on the horizon.

Importance: Amazon.com deemed investment into these two areas as critical in their bid to stay ahead of competitors. Payment of dividends to shareholders suffered as a result (0.46 cents per share in 2006 compared to 0.81 cents per share in 2005). Amazon.com will therefore need to consider such requirements and its implication on reported profit when orchestrating their desired strategic plan.

5.1.5. Gearing, Debt and Capital Structure

The gearing ratio below, Figure 6, (debt/equity) shows the proportion of debt or long term borrowing to capital employed. In 2005, 82% of the company’s finance was obtained through borrowing. Amazon reduced this to 68% in 2006. Such factors will need to be considered when considering other strategic options. Gearing leads to in-

Figure 4. Revenue to cost of sales. Source: Amazon.com.

Figure 5. Revenue and retained profit reviewed. Source: Amazon.com.

Source: Amazon.com.

Figure 6. Gearing trend debt/equity. Source: Amazon.com.

terest payments, decreasing the reported profit levels. Amazon reduced their interest cost by $14 million in 2006 as a result of the change in capital structure. Such progress has continued into 2007, with the company holding it the lowest amount of debt since 1998.

Importance: New projects need to be financed and therefore the need to borrow external and the implications of doing so should be considered by Amazon.com. Nonetheless, Table 1 shows that interest cover has been increasing year on year. This ratio measures the ability to meet interest payments. Therefore, the 2007 figure of 8.5 suggests that Amazon.com can meet their interest payments eight and a half times over, a favorable ratio which will stand them in good stead if future strategies require the attainment of extra finance from debt providers.

5.2. Amazon.com’s External Appraisal Approach

The external environment is referred to as the macro-environment. This includes the broad environmental factors which will affect organizations at various levels. It is important to consider the potential impact of the external factors on the individual organizations [31] .

The design school model calls for both external and internal appraisals. An external appraisal helps an organization to understand threats and opportunities that are out there in the market. The internal assessment helps the organization to understand its strengths and weaknesses. The “Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats” (SWOT) tool is one that most people are familiar with and stems from the design school model.

To do this, Amazon conducted the external analysis using the following analysis frameworks:

Ÿ PESTEL Analysis;

Ÿ Industry and Competitor Analysis;

Ÿ Competitor Analysis;

Ÿ Global Internet Trends;

Ÿ GE Matrix.

5.2.1. PESTEL Analysis

A PESTEL analysis is a framework or tool used by marketers to analyse and monitor themacro-environmental factors that have an impact on an organisation. The results are used to identify threats and weaknesses which are used in a SWOT analysis. (Professional Academy) [32] . An analysis of Amazon.com’s PESTEL are show in Table2

5.2.2. Summary of PESTEL

Political, economic, social, technological progress indicates an increasing and attractive market to be exploited by Amazon.com. The Chinese and Indian markets have shown exceptional growth. The use of internet as a social networking channel has created new opportunities to be exploited. Additionally, according to Stern et al.

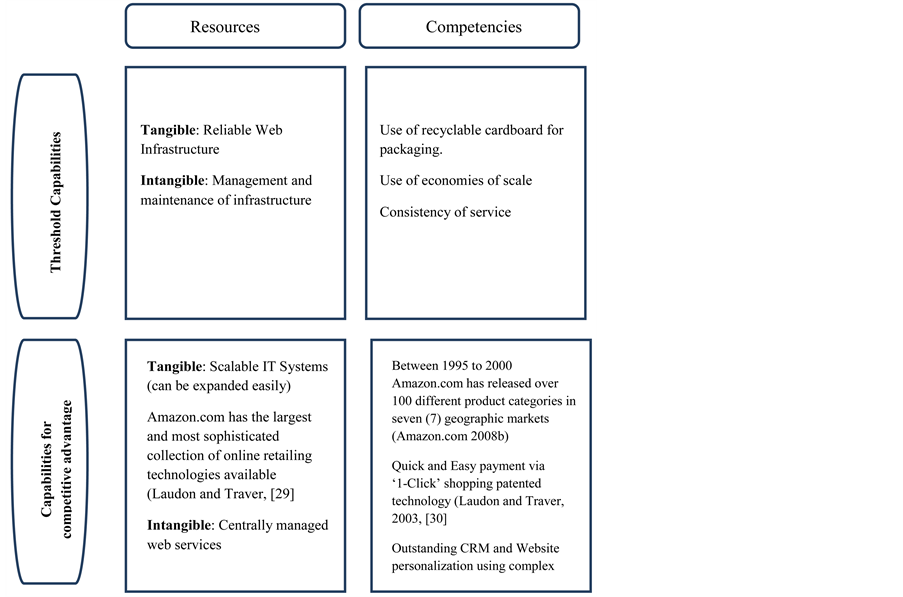

Ÿ 5.2.5. Summary of Key Findings from Porter’s Five Forces

Ÿ The competitive rivalry amongst the e-retailing industry is intense. From some of the largest to the smallest companies, dotcom businesses are abundant, making competition intense. Amazon.com competes directly with big firms such as Barnes and Noble and Ebay.

Ÿ The threat of new entrants that are able to compete directly with Amazon.com is low.

Ÿ The strong brand image of Amazon.com should be an advantage in any price wars [46] .

5.2.6. Competitor Analysis

Given the scope of Amazon.com’s product range, there are hundreds of websites that Amazon.com competes with. However, for the purpose of economies of scale, many online retailers are either increasing product line breadth for existing markets, penetrating new markets with existing products or both. In order to capture the competitiveness of such firms within the online retail industry, strategic group analysis places emphasis on product line breadth and geographic markets served. From this perspective eBay.com remains a top player within the group with over twenty-nine (29) geographic locations and twenty-two (22) product categories. Amazon.com boasts of seven (7) geographic locations and eleven (11) product categories. Amazon.com’s position intensifies the urgency to expand both product line breadth and market presence in its competition with leader eBay.com as indicated by Pitt and Lei [47] . This is shown in Figure 7.

After the competitor analysis the following was found:

Ÿ Barnes and Noble.com is seen to be a direct competitor with Amazon.com in books and lifestyle goods. However, Amazon.com has a wider product portfolio.

Ÿ Wal-Mart.com—Similar price and wider product portfolio (e.g. pharmaceutical, contact lenses and photo printing services).

Ÿ Ebay.com—Wider product portfolio and geographic scope.

Some key competitors like Wal-Mart and Tesco pose more competitive threats since they have physical stores meanwhile eBay.com has a wider geographical scope and product portfolio. Amazon.com has to adapt its strategies to address these competitive threats [48] .

6. GE Matrix

GE matrix defines the general electric matrix which says about the portfolio of the business and the collection of products and business makes the company. It is suggesting that the portfolio of the business should be the best and it should fit the best so that it will define the strengths of the company and it will help in creating the attractive opportunities for the company.

A GE Matrix has been used to identify the attractiveness and competitive position of the markets that Amazon.com operates in, using the indictors as identified by Johnson et al. [63] . As previously discussed, all markets are facing similar conditions, however China and the USA appear the most attractive as they are the largest and most dynamic markets. China and Canada have the weakest positions within their markets, suggesting that investment is required for improvement. The other markets have strong positions within the industry.

From both of these exercises, we can summarized Amazons strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats in Table 3 below.

Amazon used the TOWS matrix to help it look at options, and to ultimately identify high leverage strategies. Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats are looked at in a more systematic way than in a typical SWOT analysis. A TOWS analysis (Table 4) helps one to focus on: leveraging strengths, avoiding weaknesses, make the most of opportunities, and manage threats.

For each of the inner four portions of Table 4 (e.g. SO, ST, WO, WT), Amazon asked the following questions:

Ÿ Strengths and Opportunities (SO): How can we best employ our strengths to take advantage of the opportunities in front of us?

Ÿ Strengths and Threats (ST): How can we use our strengths to avoid threats?

Ÿ Weaknesses and Opportunities (WO): How can we use opportunities to overcome the weaknesses?

Ÿ Weaknesses and Threats (WT)—How can we minimize our weaknesses and manage the threats?

7. Conclusions

The “design school” of strategic management, focuses on a non-complex model that perceives the process of strategic formation as a design process to reach a balance between internal distinctive competence and external threat and opportunity.

The design school represents the most influential view of the strategy-formation process. In the words of this school’s best-known advocates: Economic strategy will be seen as the match between qualifications and opportunity that positions a firm in its environment? Christensen, Andrews, Bower, Hamermesh, and Porter in the Harvard Policy Textbook.

[43] as environmental awareness increases globally it is important that Amazon.com’s strategy support environmentally friendly activities. The global nature of Amazon.com’s activities also suggests that strategies developed should comply with the different legal obligations internationally.5.2.3. Industry and Competitor Analysis

The analysis on industry and competitor environment is important for organizations, because it is useful for managers to understand the competitive forces acting on and between the organizations in the same industry [44] .

5.2.4. Porters Five Forces in the E-Retailing Industry

Porter’s five forces analysis is used to assess the attractiveness of different industries, and therefore, it can help in illustrating the sources of competition in a particular industry [45] . This is indicated in Figure 7.

Source: Author’s construct/Amazon.com.

Table 4. Amazon.com’s TOWS Matrix [64] .

Source: Amazon.com.

In spite of criticizing assumptions and application, the design school provided strategic vocabulary to discuss grand strategy and introduced the central concept that strategy represents a fundamental fit between external opportunity and internal capability. This concept of ‘fit’ is being developed today into a dynamic process of adjustment.

There are perhaps four conditions in which an organization could benefit from the design school approach:

Ÿ When a single brain can handle all the information relevant to strategy formation.

Ÿ When that brain has a full, detailed, intimate knowledge of the situation (facts and emotions).

Ÿ The situation will remain stable or at least predictable during the strategic period.

Ÿ The organization is prepared to cope with a centrally articulated strategy.

Strategy is a grand design that requires a grand designer and there is a process of designing that leads to outputs called designs. The design school has focused on the process, not the product. This makes it over simplified and restricted in application but has contributed profoundly as an informing idea to the development of strategic management as a whole.

The design school’s major contribution is that it has developed important vocabulary by which to discuss grand strategy and has provided the central notion that strategy represents a fundamental fit between external opportunity and internal capability and informing idea.

References

- David, F.R. (1995) Strategic Management. 5th Edition, Prentice Hall, London.

- Newman, W.H. (1953) Administrative Action. Prentice Hall, New York.

- Tzu, S. (1971) The Art of War (S. B. Griffith, translator). Oxford University Press, New York, xi.

- Mintzberg, H., et al., (1998) Strategy Safari: A Guided Tour through the Wilds of Strategic Management. Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River.

- Mintzberg, H. (1990) The Design School: Reconsidering the Basic Premises of Strategic Management. Canada Strategic Management Journal, 11, 171-195. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250110302

- Learned, E.P., Christensen, C.R., Andrews, K.R. and Guth, W.D. (1965) Business Policy: Text and Cases. Homewood/Ill, Irwin.

- Selznick, P. (1962) Leadership in Administration: A Sociological Interpretation. Harper & Row, New York, 43-107.

- Chandler Jr., A.D. (1962/1998) Strategy and Structure: Chapters in the History of the American Industrial Enterprise. MIT Press, Cambridge.

- Selznick, P. (1957) Leadership in Administration: A Sociological Interpretation. Harper & Row, New York, 62, 67-68.

- Andrews, K.R. (1971) The Concept of Corporate Strategy. Irwin, Homewood.

- Christensen, C.R., Andrews, K.R., Bower, J.L., Hamermesh, R.G. and Porter, M.E. (1982 and 1987) Business Policy: Text and Cases. 5th and 6th Editions, Irwin, Homewood.

- Rumelt, R.P. (1979) Evaluation of Strategies: Theory and Models. In: Schendel, D.E. and Hofer, C.W., Eds., Strategic Management: A New View of Business Policy and Planning, Little, Brown, Boston.

- Laudon, K.C. and Traver, C.G. (2002) E-Commerce: Business, Technology, Society. Addison Wesley, Boston.

- Thomson Street Events (2014) Amazon.com, Inc. at Credit Suisse’s 2007 Annual Technology Conference Transcript November 27, 2007. Alacra Store, New York. http://www.alacrastore.com/thomson-streetevents-transcripts/Amazon-com-Inc-at-Credit-Suisse-s-2007-Annual-Technology-Conference-T1704428

- Johnson, G., Scholes, K. and Whittington, R. (2008) Exploring Corporate Strategy: Text and Cases. 8th Edition, Prentice Hall, Harlow.

- Amit, R. and Zott, C. (2001) Value Creation in E-Business. Strategic Management Journal, 22, 493-520.

- Laseter, T., Houston, P., Wrigth, J.L. and Park, J.Y. (2000) Amazon Your Industry: Extracting Value from the Value Chain. Strategy + Business, Issue 20. http://www.strategy-business.com/article/10479?gko=7b809

- Johnson, G., Scholes, K. and Whittington, R. (2008) Exploring Corporate Strategy: Text and Cases. 8th Edition, Prentice Hall, Harlow.

- Hooley, G., Saunders, J. and Piercy, N.F. (2001) Marketing Strategy and Competitive Positioning. 3rd Edition, Pearson Education, Upper Saddle River.

- Cone, E. (2008) Amazon.com at Your Service. CIO Insight. Lexis-Nexis Database.

- Ward, K. (2012) Amazon Is Adding 400 Jobs in Fayette; A Variety of Permanent, Full-Time Positions Offered. Lexington Herald Leader.

- Howells, J. (2012) Walmart Lawsuit against Amazon.com Could Be a Blow for Ecommerce. Global Newswire.

- The Economist (2012) Amazon.com—Click to Download. The Economist.

- Neel, D. (2012) Amazon.com Becomes a Hewlett-Packard Shop. InfoWorld.

- Business Wire (2012) Amazon.com Headlines List of Key Not Addresses for Linux World San Francisco and Next Generation Data Center. Business Wire.

- The Economist (2012) Amazon.com—Click to Download. The Economist.

- Porter, M.E. (2004) Competitive Advantage. Free Press, New York.

- Amazon.com (2014) A Case Study. http://www.studymode.com/essays/Amazon-Com-a-Case-Study-51621041.html

- Laudon, K. and Traver, C. (2003) E-Commerce: Business, Technology, Society 2. Addision-Wesley, Boston, 593.

- Laudon, K. and Traver, C. (2003) E-Commerce: Business, Technology, Society 2. Addision-Wesley, Boston, 102.

- Johnson, G., Scholes, K. and Whittington, R. (2006) Exploring Corporate Strategy. Enhanced Media Edition, Prentice Hall, Harlow.

- Professional Academy (2013) Marketing Theories—PESTEL Analysis. http://www.professionalacademy.com/news/marketing-theories-pestel-analysis

- Held, D., McGrew, A., Goldblatt, D. and Perraton, J. (1999) Global Transformations: Politics, Economics and Culture. Polity Press, Cambridge.

- The Times Online (2008) A Billion Reasons to Invest in India. 27th October 2007.

- Euromonitor International (2008) Euromonitor.com. 2008 Report. http://athens.portal.euromonitor.com/portal/server.pt?control=SetCommunity&CommunityID=207&PageID=720&cached=false&space=CommunityPage

- Michael, A.S. (2008) EMarketer Online. Ten Key Online Predictions for 2008. http://www.marketingcharts.com/direct/ten-key-online-predictions-for-2008-2924/

- Sorce, P., Perotti, V. and Widrick, S. (2005) Attitude and Age Differences in Online Buying. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 33, 122-132. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/09590550510581458

- Miniwatts Marketing Group (2001-2013) World Internet Users and Population Statistics. http://www.internetworldstats.com/stats.htm

- Matthews, H.S., Hendrickson, C. and Soh, D. (2001) The Net Effect: Environmental Implications of e-Commerce and Logistics. Proceedings of the 2001 Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineering (IIIEE) International Symposium on Electronics and the Environment, Denver, CO, 5-9 May 2001.

- Bange, V. (2007) Online Security: Legal Issues. New Media Age, London, 11 January 2007, 10.

- Zugelder, M.T., Flaherty, T.B. and Johnson, J.P. (2000) Legal Issues Associated with International Internet Marketing. International Marketing Review, London, 17, 253-271.

- Yan, W. (2005) The Electronic Signatures Law: China’s First National E-Commerce Legislation. Intellectual Property & Technology Law Journal, Clifton, 17, 6-11.

- Stern, N., Peters, S., Bakhshi, V., Bowen, A., Cameron, C., Catovsky, S., Crane, D., Cruickshank, S., Dietz, S., Edmonson, N., Garbett, S.L., Hamid, L., Hoffman, G., Ingram, D., Jones, B., Patmore, N., Radcliffe, H., Sathiyarajah, R., Stock, M., Taylor, C., Vernon, T., Wanjie, H. and Zenghelis, D. (2006) Stern Review: The Economics of Climate Change. HM Treasury, London.

- Johnson, G., Scholes, K. and Whittington, R. (2006) Exploring Corporate Strategy. Enhanced Media Edition, Prentice Hall, Harlow, 75.

- Johnson, G., Scholes, K. and Whittington, R. (2006) Exploring Corporate Strategy. Enhanced Media Edition, Prentice Hall, Harlow, 78.

- (2012) 12manage: Management Communities, Outside-In Business Strategy; Explaining the Five Competitive Forces of Michal Porter. http://www.12manage.com/methods_porter_five_forces.html

- Pitts, R. and Lei, D. (2006) Strategic Management. 4th Edition, Thomson South-Western.

- Teather, D. (2007) Challenge Amazon: Amazon Is Pretty Much the Undisputed Champion of Internet Book Sales in the UK, but Might an Ambitious New Competitor Challenge Its Market Dominance? The Book Seller.

- 12manage: Management Communities, Outside-In Business Strategy; Explaining the Five Competitive Forces of Michal Porter. http://www.12manage.com/methods_porter_five_forces.html

- Stockport, G.J. (2010) Amazon.com: 2007-Early 2009. Crawley.

- Johnson, G., Scholes, K. and Whittington, R. (2006) Exploring Corporate Strategy. Enhanced Media Edition, Prentice Hall, Harlow.

- Vakil, B. (2014) Analysis of Business Environment of Amazon.com Inc. http://business.wikinut.com/Analysis-of-Business-Environment-of-Amazon.com-Inc/39oq9hbh/

- Ward, M.R. (2001) Will Online Shopping Compete More with Traditional Retailing or Catalogue Shopping? Netnomics, 3, 103-117. http://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/klu/netn/2001/00000003/00000002/00337873

- RedOrbit (2007) Students Get a Break by Renting, Rather than Buying, Textbooks [Online]. http://www.redorbit.com/news/education/1266716/students_get_a_break_by_renting_rather_than_buying_textbooks/index.html

- Bennett, J. (2007) Porter’s Five Forces Model and Internet Competition. http://EzineArticles.com/?expert=Jeffrey_Bennett

- Mallon, C. (2014) Porter’s Five Forces Analysis. http://ezinearticles.com/?Porters-Five-Forces-Analysis&id=15116

- Cassiman, B. and Sieber, S. (2002) The Impact of Internet on Market Structure. IESE Business School. http://www.iese.edu/es/files/impact%20of%20the%20internet%20on%20market%20structure,%20the_tcm5-5891.pdf

- Amazon.com Inc. (2011) Annual Report. http://phx.corporate-ir.net/phoenix.zhtml?c=97664&p=irol-reportsannual

- Chaffey, D. Amazon.com Case Study. http://www.smartinsights.com/digital-marketing-strategy/online-business-revenue-models/amazon-case-study/

- Hadro, J. (2008) Amazon Acquires Shelfari. Library Journal, 133, 20.

- Wiley, et al. (2001) E-Commerce: Fundamentals and Applications, Consumer-Oriented Ecommerce. http://tharam.it.uts.edu.au/slide/ch11.ppt

- McGrath, L.C. and Heiens, R.A. (2003) Beware the Internet Panacea: How Tried and True Strategygot Sidelined. Journal of Business Strategy, 24, 24-28. http://www.emeraldinsight.com/10.1108/02756660310509460

- Johnson, G., Scholes, K. and Whittington, R. (2006) Exploring Corporate Strategy. Enhanced Media Edition, Prentice Hall, Harlow, 320.

- Kendrick, S. (2012) The TOWS Matrix: Putting a SWOT Analysis into Action. http://www.volunteerhub.com/blog/the-tows-matrix-putting-a-swot-analysis-into-action/