Theoretical Economics Letters

Vol.06 No.03(2016), Article ID:67117,8 pages

10.4236/tel.2016.63051

An Elementary Proof That Well-Behaved Utility Functions Exist

Mark Voorneveld, Jörgen W. Weibull

Department of Economics, Stockholm School of Economics, Stockholm, Sweden

Copyright © 2016 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received 21 March 2016; accepted 3 June 2016; published 6 June 2016

ABSTRACT

Starting from an intuitive and constructive approach for countable domains, and combining this with elementary measure theory, we obtain an upper semi-continuous utility function based on outer measure. Whenever preferences over an arbitrary domain can at all be represented by a utility function, our function does the job. Moreover, whenever the preference domain is endowed with a topology that makes the preferences upper semi-continuous, so is our utility function. Although links between utility theory and measure theory have been pointed out before, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first time that the present intuitive and straight-forward route has been taken.

Keywords:

Preferences, Utility Theory, Measure Theory, Outer Measure

1. Introduction

When treating utility theory, traditional economic textbooks discuss two disparate cases in considerable detail: the potential non-existence of utility functions for complete and transitive preference relations on non-trivial connected Euclidean domains―usually illustrated by lexicographic preferences (Debreu, [1] )―and the existence of continuous utility functions for complete, transitive and continuous preferences on connected Euclidean domains; see, e.g. Mas-Colell, Whinston, and Green [2] . Yet, for many purposes, in particular for the existence of a best alternative in a compact set of alternatives, a weaker property―upper semi-continuity―suffices. Hence, the reader of such a textbook treatment might wonder if there exist upper semi-continuous utility functions, and whether this is true even if the domain is not connected.

The purpose of this note is primarily pedagogical: it provides necessary and sufficient conditions for the existence of upper semi-continuous utility functions on arbitrary domains; see Theorem 2 and the text following it. Our approach is intuitive, constructive, and although it uses a measure-theoretic idea, it remains easily accessible to readers without any knowledge of measure theory.

Measure theory is the branch of mathematics that deals with the question of how to define the “size” (area/ volume) of sets. The main pedagogical point of our paper is to formalize a direct, intuitive link with utility theory: given a binary preference relation on a set of alternatives, the “better” an alternative is, the “larger” is its set of worse alternatives. So if one can measure the “size” of the set of worse elements, for each given alternative, one obtains a utility function.

To be a bit more precise, measure theory starts out by first defining the “size”―measure―of a class of “simple” sets, such as bounded intervals on the real line or rectangles in the plane, and then extends this definition to other sets by way of approximation in terms of simple sets. The outer measure is the best such approximation “from above”. This is illustrated in Figure 1: having defined the size of rectangles in the plane, we can assign a size also to more general sets S in the plane by covering it with rectangles. That can be done in many ways, but to get a good approximation, one wants a covering that resembles S as closely as possible. Roughly speaking, the rectangles covering S should not stick out from S a lot. So the outer measure S is the infimum, over all coverings by a countable number of rectangles, of the sum of the rectangles’ areas. In more general settings, the outer measure is defined likewise as the infimum over coverings whose sizes have been defined (see, for instance, Rudin [3] , p. 304; Royden [4] , Sec. 3.2; Billingsley [5] , Sec. 3; Ash [6] , p. 14).

Figure 1. A set S and an approximation of its size using a covering.

We follow this approach to define the utility of an alternative as the outer measure of its set of worse alternatives. We start by doing this for a countable set of alternatives, where this is relatively simple and then proceed to arbitrary sets.

Our paper is not the first to use tools from measure theory to address the question of utility representation: pioneering papers are Neuefeind [7] and Sondermann [8] . See Bridges and Mehta ( [9] , sections 2.2 and 4.3) for a textbook treatment. However, our approach differs fundamentally from these precursors. Firstly, we only use the basic notion of outer measure, while the mentioned studies impose additional topological and/or measure- theoretic constraints.1 To the best of our knowledge, the logical connection between outer measure and utility has never been made before. We hope that this link between utility theory and measure theory is more explicit, intuitive and mathematically elementary than the above-mentioned approaches. Let us stress the generality of this result. Although the utility function in terms of outer measure is simple and intuitive, it delivers the most general results possible. Firstly, whenever preferences over an arbitrary set of alternatives can be represented by a utility function, our function does the job (cf. Theorem 1). Secondly, whenever the set of alternatives is endowed with a topology that makes preferences upper semi-continuous, also our utility function becomes upper semi-continuous (cf. Theorem 2).

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 recalls definitions and provides notation. Section 3 contains the main results; one proof is in the Appendix.

2. Preliminaries

Let preferences on an arbitrary set X be defined in terms of a binary relation  (“weakly preferred to”) which is:

(“weakly preferred to”) which is:

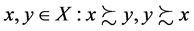

complete: for all , or both;

, or both;

transitive: for all : if

: if  and

and , then

, then .

.

As usual,  means

means , but not

, but not , whereas

, whereas  means that both

means that both  and

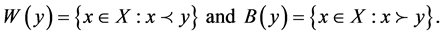

and . The sets of elements strictly worse and strictly better than

. The sets of elements strictly worse and strictly better than  are denoted

are denoted

For

A preference relation

Any such function u is called a utility function for the preference relation in question.

3. Constructing the Utility Function

This section makes the intuitive argument from the introduction precise: given a binary preference relation on a set of alternatives, the “better” an alternative is, the “larger” is its set of worse alternatives. So if one can measure the “size” of the set of worse elements, for each given alternative, one obtains a utility function.

Although our construction borrows its main idea from measure theory, it ought to be stressed that no topological or measure-theoretic assumptions are needed: the way we define the utility function works whenever the necessary and sufficient conditions for the existence of a utility function are satisfied. The purpose of the more technical second subsection is to show a stronger result, namely that our utility function automatically inherits a commonly imposed continuity property of the preferences. Here, of course, some topology is required to define continuity.

3.1. Existence

A complete, transitive binary relation

Roughly speaking, countably many alternatives suffice to keep all pairs

Note that Jaffray order separability is satisfied automatically if the domain X itself is countable: you can simply take D equal to X. For uncountable domains, like commodity bundles in

The set D in the definition of Jaffray order separability is countable, so let

weight

We can extend this procedure from D to X as follows. Let

Notice that

where the infimum is taken over all countable collections

Define

It is easily seen that this gives the desired utility representation:

Theorem 1. Consider a complete, transitive, Jaffray order separable binary relation

Proof. By definition,

and the outer measure

We prove that u represents

So finding a utility function is not so difficult; in fact, the literature we cite gives many other constructions as well. Our main message in this subsection is rather that our approach is from scratch, following an elementary idea of assigning an appropriate size to the set of worse elements. And it works without any topological or measure-theoretic assumptions on the domain: whenever preferences over an arbitrary set X can be represented by a utility function (i.e., they are complete, transitive, Jaffray order separable), our function does the job.

Perhaps a more important insight is that it automatically inherits a standard continuity property that is often imposed to guarantee the existence of most preferred elements; this part of the paper is a bit more technical and requires some further definitions.

3.2. Upper Semi-Continuity of the Outer-Measure Utility

By letting in a little bit of topology, one can use the above to obtain results concerning the existence of upper semi-continuous utility functions. Given a topology on X, preferences

continuous if for each

upper semi-continuous (usc) if for each

Similarly, a function

Three important topologies are, firstly, the order topology, generated by (i.e., the smallest topology containing) the collections

collection

As mentioned in the introduction, although one often appeals to continuity to establish existence of most preferred alternatives, the weaker requirement of upper semi-continuity suffices: consider a complete, transitive, usc binary relation

compactness, there are finitely many

From Theorem 1, we already know that our utility function defined in (4) represents preferences in all scenarios where utility functions exist. Our next result shows that whenever X is endowed with a topology that makes the preferences

Theorem 2. Consider a complete, transitive, Jaffray order separable binary relation

The proof is in the appendix. Corollaries 1 and 2 below provide applications of this result. Consider preferences

Corollary 1. If

Also Rader [12] establishes existence of a usc utility function under the conditions of Corollary 1. However, we obtain the result as a special case of Theorem 2, which holds under weaker conditions and gives a specific usc utility function building upon basic measure-theoretic intuition.

Sondermann [8] calls a preference relation

Perfect separability implies Jaffray order separability (Jaffray, [10] ), so we obtain the following result, due to Sondermann [8] , as a special case:

Corollary 2. (Sondermann, [8] , Corollary 2) Consider a complete, transitive, perfectly separable binary relation

Also here, the “value added” of Theorem 2 is that it provides a specific usc utility function building upon basic measure-theoretic intuition.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Avinash Dixit, Klaus Ritzberger, and Peter Wakker for comments and to the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation and the Wallander-Hedelius Foundation for financial support.

Cite this paper

Mark Voorneveld,Jörgen W. Weibull, (2016) An Elementary Proof That Well-Behaved Utility Functions Exist. Theoretical Economics Letters,06,450-457. doi: 10.4236/tel.2016.63051

References

- 1. Debreu, G. (1954) Representation of a Preference Ordering by a Numerical Function. In: Thrall, M., Davis, R.C. and Coombs, C.H., Eds., Decision Processes, John Wiley and Sons, New York, 159-165.

- 2. Mas-Colell, A., Whinston, M.D. and Green, J.R. (1995) Microeconomic Theory. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

- 3. Rudin, W. (1976) Principles of Mathematical Analysis. 3rd Edition, McGraw-Hill, New York.

- 4. Royden, H.L. (1988) Real Analysis. 3rd Edition, Prentice-Hall, New Jersey.

- 5. Billingsley, P. (1995) Probability and Measure. 3rd Edition, John Wiley and Sons, New York.

- 6. Ash, R.B. (2000) Probability and Measure Theory. 2nd Edition, Academic Press, London/San Diego.

- 7. Neuefeind, W. (1972) On Continuous Utility. Journal of Economic Theory, 5, 174-176.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0022-0531(72)90126-3 - 8. Sondermann, D. (1980) Utility Representations for Partial Orders. Journal of Economic Theory, 23, 183-188.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0022-0531(80)90004-6 - 9. Bridges, D.S. and Mehta, G.B. (1995) Representations of Preference Orderings. Springer-Verlag, Berlin.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-51495-1 - 10. Jaffray, J.-Y. (1975) Existence of a Continuous Utility Function: An Elementary Proof. Econometrica, 43, 981-983.

http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1911340 - 11. Fishburn, P.C. (1970) Utility Theory for Decision Making. John Wiley and Sons, New York.

- 12. Rader, T. (1963) The Existence of a Utility Function to Represent Preferences. Review of Economic Studies, 30, 229-232.

http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2296323

Appendix: Proof of Theorem 2

Recall that

and that the outer measure

To establish upper semi-continuity, let

Case 1: There is no

and

show that

Case 2: There is a

Case 2A: There is a

Case 2B: For each

Since

and

Hence, for each

This concludes the proof. As a final remark, observe that due to the completeness of preferences, the countable collection

Whenever x is not a most preferred alternative in X, Jaffray order separability assures that there is a

Jaffray ( [10] , p. 982) defines utility similar to the expression in the previous line, but, so to speak, from the opposite direction: he defines utility of an alternative x as the supremum of the utility of worse ones from a suitably chosen countable set.

NOTES

1Neuefeind [7] restricts attention to finite-dimensional Euclidean spaces and assumes that indifference sets have Lebesgue measure zero. Sondermann [8] assumes that preferences are defined on a probability space or a second countable topological space; see also Corollary 2 below.

2See Fishburn ( [11] , Section 3.1) or Bridges and Mehta ( [9] , Section 1.4) for alternative necessary and sufficient separability conditions.

3If there is a worst element in X (an

4In class, we usually illustrate this common construction of utility functions on a countable domain D using chocolate bars: since D is countable, we may label its elements

5E.g., consumer preferences over a commodity space