Theoretical Economics Letters

Vol.4 No.1(2014), Article ID:42959,6 pages DOI:10.4236/tel.2014.41011

International Crises, Characterization of Contagion and Social Well-Being in Developing Countries: A Theoretical Model

Department of Economics, University of Toulon, Toulon, France

Email: giscard-assoumou-ella@etud.univ-tln.fr

Received October 14, 2013; revised November 14, 2013; accepted November 21, 2013

ABSTRACT

This paper has two objectives: to characterize the exposure of developing countries to the international income, prices and monetary shocks and to calculate the social well-being in the period of contagion. Firstly, we develop a theoretical model with a world composed of two countries (developed and developing countries) and measure the level of the exposure of income in developing country to the external shocks trough external trade, international tourism, migrant transfers, external debt, foreign aid, FDI and other private financial flow channels. And, we characterize imported inflation in studying the effect of the international shocks on real exchange rate. Secondly, we search the social well-being. The results suggest that economic disequilibrium in developing country is socially optimal and that the dependence of its income to the domestic industry is necessary to reduce contagion. This conclusion is important for African countries because they import finished products for the households’ consumption. In these conditions, they are exposed to the imported inflation. The domestic monetary and tax policies are not adapted to fight against inflation. Also, they produce and export raw materials essentially toward industrialized economies. Thus, they must develop the domestic industry in order to influence the demand (or prices) of raw materials and to substitute imports by domestic goods in period of hyper-inflation in advanced economies in order to reduce imported inflation.

Keywords:International Crises; Social Well-Being; Imported Inflation

1. Introduction

In the history of the contemporary economies, it observes the recurrence of the economic and financial crises in advanced economies that affect developing countries [1-3]. In fact, income in developing countries is determined by the following external variables: exports and imports of goods and services [4-9], international tourism [10-13], migrant transfers [14-17], external debt [18-20], foreign aid [21-24], Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) and other private financial flows [25-30]. However, these external variables are impacted by the international shocks. In addition, African countries, for example, export raw materials toward advanced economies and import finished goods for the household consumption. Thus, they are exposed to the fluctuations of the international prices of raw materials and to the imported inflation.

In these conditions, the objectives of this paper are to characterize the levels of the exposure of income in developing countries to the international income, prices and monetary shocks through exports and imports of goods and services, international tourism, migrant transfers, external debt, foreign aid, FDI and other private financial flows channels, and to characterize the imported inflation through the effect of the external shocks on real exchange rate. The final objective is to study the social well-being in developing countries in period of contagion. Firstly, we calculate the fluctuations of income in developing countries through the effects of international shocks on the external variables and characterize imported inflation. Secondly, we search the best economic situation in developing countries in order to reduce the exposure to the international shocks.

The paper is organized as following: the formalization of the model is subject of Section 2. In the Section 3, we calculate the social well-being.

2. Model Formalization

We develop a model of the exposure of developing countries to the international income, prices and monetary shocks and to the imported inflation, with the following hypothesizes:

H1: the world is composed of two countries: a developing country (B) that exports the raw materials and imports finished goods for the household consumption, and a developed country (A) that imports the raw materials for his industry and exports finished products toward (B) [4,31].

H2: (B) is composed by a sector exposed to the shocks of (A) and the prices of raw materials shocks, and a non-exposed sector (Z). According [8], Z represents the domestic determinants of income in developing country.

H3: there is a significant relationship between income in (B) and external trade variables [4-9], international tourism arrivals [10-13], migrant transfers [14-17], external debt [18-20], foreign aid foreign aid [21-24], Foreign Direct Investment and other private financial flows [25-30].

H4: the income, price and monetary shocks of (A) and the price of raw materials shocks impact the external variables enumerated in H3 [32-39].

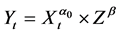

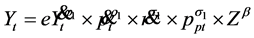

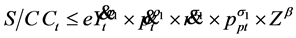

Using H1, H2 and H3, the relationship between income in (B) and external variables can be written in this form:

(1)

(1)

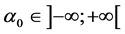

with  and

and

Y represents the income, X the vector of the foreign variables enumerated in H2,  the elasticity of Y with respect to X,

the elasticity of Y with respect to X,  the elasticity of Y with respect to Z and t, the time.

the elasticity of Y with respect to Z and t, the time. : In the recent literature review concerning the effects of the variables included in the vector X on the domestic income in developing countries, it is demonstrated that the relationship can be positive or negative. In the case of the imports, for example, they have a positive effect on the domestic income if they are the imports of capital goods for domestic investment [40,41], and the effect is negative concerning the imports of consumption goods [9,42]. In the case of migrant transfers, the effect on the domestic income is ambiguous. There is a positive relationship between these two variables [43-45]. The effect can be negative in taking into account the levels of education of the migrants [46-49].

: In the recent literature review concerning the effects of the variables included in the vector X on the domestic income in developing countries, it is demonstrated that the relationship can be positive or negative. In the case of the imports, for example, they have a positive effect on the domestic income if they are the imports of capital goods for domestic investment [40,41], and the effect is negative concerning the imports of consumption goods [9,42]. In the case of migrant transfers, the effect on the domestic income is ambiguous. There is a positive relationship between these two variables [43-45]. The effect can be negative in taking into account the levels of education of the migrants [46-49]. : We suppose that the vector Z has a positive impact on the domestic income in developing countries ([4]).

: We suppose that the vector Z has a positive impact on the domestic income in developing countries ([4]).

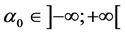

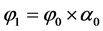

Using H4, foreign variables of (B) can be written in this form:

(2)

(2)

with ,

,  ,

,  and

and

![]() represents the income in (A),

represents the income in (A), ![]() the inflation in (A),

the inflation in (A),  the central Bank’ director interest rate in (A),

the central Bank’ director interest rate in (A),  the world price of a raw material exported by (B),

the world price of a raw material exported by (B),  the elasticity of X with respect to

the elasticity of X with respect to![]() ,

,  the elasticity of X with respect to

the elasticity of X with respect to![]() ,

,  the elasticity of X with respect to

the elasticity of X with respect to  and

and  the elasticity of X with respect to

the elasticity of X with respect to . We multiply X by e (the nominal exchange rate) for the conversion in money of (B).

. We multiply X by e (the nominal exchange rate) for the conversion in money of (B). : Income in (A) has a positive effect on foreign variables of (B).

: Income in (A) has a positive effect on foreign variables of (B). : The effect of inflation in (A) on some external variables of (B) can be positive or negative. In the case of the migrant transfers, for example, inflation in (A) decreases the purchasing power of the migrants, and therefore their transfers.

: The effect of inflation in (A) on some external variables of (B) can be positive or negative. In the case of the migrant transfers, for example, inflation in (A) decreases the purchasing power of the migrants, and therefore their transfers. : The effect of monetary policy in (A) on the external variables of (B) can be positive or negative. An expansive monetary policy that increases income and the demand, for example, can decrease the exports of (A) toward (B) (the exports of (A) are the imports of (B)). On the other hand, this monetary policy can increase the migrant transfers.

: The effect of monetary policy in (A) on the external variables of (B) can be positive or negative. An expansive monetary policy that increases income and the demand, for example, can decrease the exports of (A) toward (B) (the exports of (A) are the imports of (B)). On the other hand, this monetary policy can increase the migrant transfers. : The effect of price of raw material on the external variables can be positive or negative. A decrease in this variable reduces the value of the exports of (B) and increases the level of the migrant transfers, for example.

: The effect of price of raw material on the external variables can be positive or negative. A decrease in this variable reduces the value of the exports of (B) and increases the level of the migrant transfers, for example.

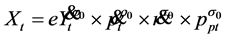

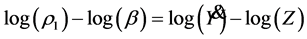

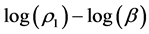

In replacing Equation (2) in (1), we have:

(3)

(3)

with ,

,  ,

,  and

and .

.

According (3), income, price and monetary policy shocks in (A) and world price of a raw material exported by (B) shock affect domestic income in (B) through exports and imports of goods and services, international tourism, migrant transfers, external debt, foreign aid, Foreign Direct Investment and other private financial flows channels. This exposure is measured by ,

,  ,

, ![]() and

and , the multiplication of the elasticity of Y with respect to X with the elasticity of X with respect to

, the multiplication of the elasticity of Y with respect to X with the elasticity of X with respect to![]() ,the elasticity of X with respect to

,the elasticity of X with respect to![]() , the elasticity of X with respect to

, the elasticity of X with respect to  and the elasticity of X with respect to

and the elasticity of X with respect to . In these conditions, (B) can measure the level of the exposure of his income according the type of the external shock and the transmission channel. According [31], it is possible to use the Equation (3) in order to characterize imported inflation in (B) through the effect of external shocks to the real exchange rate.

. In these conditions, (B) can measure the level of the exposure of his income according the type of the external shock and the transmission channel. According [31], it is possible to use the Equation (3) in order to characterize imported inflation in (B) through the effect of external shocks to the real exchange rate.

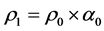

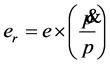

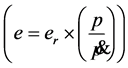

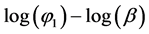

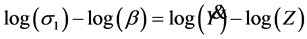

Thus, knowing that

with

with  and p, real exchange rate and inflation in (B)

and p, real exchange rate and inflation in (B)

, we apply the logarithm on Equation (3)

, we apply the logarithm on Equation (3)

and we have:

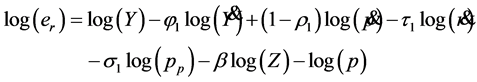

(4)

(4)

Exposure of (B) to the international shocks decreases real exchange rate. In this context, (B) is exposed to the imported inflation. In the case of African countries, for example, they produce and they export essentially raw materials toward industrialized economies [50]. Also, they import finished goods for the household consumption. In these conditions, they are exposed to the fluctuations of the international prices of the raw materials and to the imported inflation, and the monetary and tax policies are not adapted to fight against inflation. Thus, they must develop domestic industry in order to influence the demand (or prices) of raw materials and to substitute imports by domestic goods in period of imported inflation.

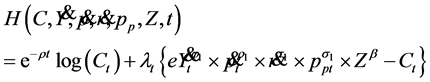

3. Social Well-Being in (B)

The social well-being in (B) represents the situation where his economy stands to the contagion of the negative shocks of (A) and the price of raw material shock. Thus, we calculate the equilibrium (disequilibrium) socially optimal in (B), knowing that total consumption  is constrained by total income

is constrained by total income![]() .

.

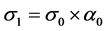

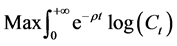

The Hamiltonian of the problem is written as following; with an instantaneous logarithmic utility function and a preference for the present  of Ramsey type:

of Ramsey type:

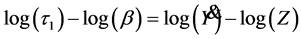

We calculate the first order conditions and we respectively represent the equilibrium (disequilibrium) socially optimal in the cases of the international income, price, monetary shocks in (A) and world price of raw material shock:

(5)

(5)

is an indicator that represents the exposure of income in (B) to the income shock in (A). His increase implies that the level of the exposure increases in developing country, and conversely in the case of a decrease. Thus, in period of contagion of an external income shock, the equilibrium in (B) is represented by (5); when the variation of Y consecutive to the variation of

is an indicator that represents the exposure of income in (B) to the income shock in (A). His increase implies that the level of the exposure increases in developing country, and conversely in the case of a decrease. Thus, in period of contagion of an external income shock, the equilibrium in (B) is represented by (5); when the variation of Y consecutive to the variation of ![]() equates the elasticity of Y with respect to Z. In this context, a decrease of income in (B) after the contagion of a negative income shock in (A) is sustained by the elasticity of Y with respect to Z. However, this equilibrium isn’t socially optimal because

equates the elasticity of Y with respect to Z. In this context, a decrease of income in (B) after the contagion of a negative income shock in (A) is sustained by the elasticity of Y with respect to Z. However, this equilibrium isn’t socially optimal because  is the good situation for (B) in period of contagion of an external negative income shock, and

is the good situation for (B) in period of contagion of an external negative income shock, and  is preferred in period of contagion of a positive income shock.

is preferred in period of contagion of a positive income shock.

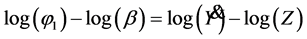

(6)

(6)

is an indicator that represents the level of the exposure of income in (B) to the price shock in (A). Equation (6) represents the equilibrium in period of contagion but isn’t socially optimal because

is an indicator that represents the level of the exposure of income in (B) to the price shock in (A). Equation (6) represents the equilibrium in period of contagion but isn’t socially optimal because  is preferred if the contagion has a negative impact on income in (B), and

is preferred if the contagion has a negative impact on income in (B), and  in the case where the contagion of the price shock increases income in (B).

in the case where the contagion of the price shock increases income in (B).

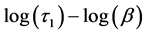

(7)

(7)

represents the level of the exposure of income in (B) to the monetary shock in (A). As the preceding cases, the equilibrium after the contagion of a monetary shock isn’t socially optimal.

represents the level of the exposure of income in (B) to the monetary shock in (A). As the preceding cases, the equilibrium after the contagion of a monetary shock isn’t socially optimal.  is preferred in period of a restrictive monetary policy in (A)

is preferred in period of a restrictive monetary policy in (A)

and  in period of an expansive monetary policy.

in period of an expansive monetary policy.

(8)

(8)

is the level of the exposure of income in (B) to the price of raw material shock. The equilibrium isn’t also socially optimal.

is the level of the exposure of income in (B) to the price of raw material shock. The equilibrium isn’t also socially optimal.  is preferred if

is preferred if  decreases and

decreases and  if

if  increases.

increases.

4. Conclusion and Political Economic Implications

The objectives of this paper are to characterize the exposure of developing countries to the international income, prices and monetary shocks, and to calculate the social well-being in period of contagion. Thus, we develop the theoretical model with a world composed of two countries: developed and developing countries. The results suggest that income in developing country is exposed to the shocks of developed country and the price of raw material shock through exports and imports of goods and service, international tourism, migrant remittances, foreign debt, foreign aid, Foreign Direct Investment, other private financial flows and real exchange rate channels. Also, economic disequilibrium is social optimal in period of contagion. The dependence to the non-exposed sector is necessary to reduce external exposure.

This conclusion is important for the African countries because they produce and export raw materials essentially. In this context, an international industrial crisis has a big impact on their economies. Also, African countries import finished goods for the household consumption. In these conditions, they are exposed to the imported inflation. The monetary and tax policies aren’t adapted to fight against inflation. If we suppose that Z includes domestic industry, for example, the development of this industry in African countries is a good opportunity for them to influence the demand (or prices) of raw materials and to substitute imports by domestic goods in period of imported inflation.

REFERENCES

- J.-M. L. Page, “Crises Financières Internationales & Risque Systémique,” Questions D’économieet de Gestion, De Boeck, 2003. http://ses.ens-lyon.fr/crises-financieres-internationales-et-risque-systemique-25628.kjsp

- R. Boyer, M. Dehove and D. Plihon, “Les Crises Financières,” Conseil D’analyse Economique, La Documentation Française, 2004. http://www.ladocumentationfrancaise.fr/var/storage/rapports-publics/044000560/0000.pdf

- Ph. Hugon, “La Crise financière et la Faiblesse des Politiques Face aux Forces du Marché,” Les Notes de L’institut de Relations Internationales et Stratégique, 2011. http://www.iris-france.org/docs/kfm_docs/docs/2011-09-crise-financiere.pdf

- G. A. Ella and C. B. Gilles, “Canal du Commerce Extérieur, Politiquespubliquesetspécialisation des PED Africains: Étudeempirique,” XXIXemes Third World Association Conference, Informal Economy and Development: Employment, Financing and Regulation in a context of Crisis, University Paris-Est Creteil Créteil, 2013. http://www.erudite.univ-paris-est.fr/evenements/colloques-et-conferences/atm-2013-communications-full-papers/?eID=dam_frontend_push&docID=25188

- M. AyhanKose and R. Riezman, “Trade Shocks and Macroeconomic Fluctuations in Africa,” Journal of Development Economics, Vol. 65, No. 1, 2001, pp. 55-80. http://www.iatp.org/files/Trade_Shocks_and_Macroeconomic_Fluctuations_in.pdf http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0304-3878(01)00127-4

- D. Dutta and N. Ahmed, “Trade Liberalization and Industrial Growth in Pakistan: A Cointegration Analysis,” Applied Economics, Vol. 36, No. 4, 2004, pp. 1421-1429. http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/0003684042000206951#.UrBs-vTuJc4 http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/0003684042000206951

- J. Thurlow, “Trade Liberalization and Pro-Poor Growth in South Africa,” Studies in Economics and Econometrics, Vol. 31, No. 2, 2007, pp. 161-179. http://reference.sabinet.co.za/document/EJC21443

- J. Mbabazi, C. Milner and O. Morrissey, “Trade Openness, Trade Costs and Growth: Why Sub-Saharan Africa Performs Poorly,” Centre for Research in Economic Development and International Trade Research Paper, CREDIT Research Papers, 2008, No. 06/08, p. 24. http://www.nottingham.ac.uk/credit/documents/papers/06-08.pdf

- A.C. F. Puente, M. B. and A. C. Poncela, “How Changes in International Trade Affect African Growth,” Economic Analysis Working PapersVol. 8, No. 1, , 2009, p. 17. http://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/43405/1/628572 999.pdf

- J. L. Eugenio-Martin, N. M. Morales and R. Scarpa, “Tourism and Economic Growth in Latin American Countries: A Panel Data Approach,” FEEM Working Paper No. 26, 2004. http://www.feem.it/userfiles/attach/Publication/NDL2004/NDL2004-026.pdf

- J. Mitchell and C. Ashley, “Pathways to Prosperity: How Can Tourism Reduce Poverty? A Review of pathways, Evidence and Methods,” Draft Report for the World Bank, 2007.

- B. Fayissa, C. Nsiah and B. Tadesse, “The Impact of Tourism on Economic Growth and Development in Africa,” Tourism Economics, Vol. 14, No. 4, 2008, pp. 807-818. http://dx.doi.org/10.5367/000000008786440229

- K. OlayinkaIdowu, “Tourism-Export and Economic Growth in Africa,” 13th African Econometrics Society (AES) Conference, Pretoria, July 2008, 32 Pages. http://www.africametrics.org/documents/conference08/day1/session2/kareem.pdf

- J. Jongwanich, “Workers’ Remittances, Economic Growth and Poverty in Developing Asia and the Pacific Countries,” United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific Working Paper, 2007, No. WP/07/01, p. 27. http://www.unescap.org/pdd/publications/workingpaper/wp_07_01.pdf

- M. A. Ajayi, M. A. Ijaiya, G. T. Ijaiya, R. A. Bello, M. A. Ijaiya and S. L. Adeyemi, “International Remittances and Well-Being in Sub-Saharan Africa,” Journal of Economics and International Finance, Vol. 1, No. 3, 2009, pp. 078-084.

- P. A. Garcia-Fuentes and P. Lynn Kennedy, “Remittances and Economic Growth in Latin America and the Caribbean: The Impact of the Human Capital Development,” Southern Agricultural Economics Association 2009 Annual Meeting, Atlanta, 2009. http://www.microfinancegateway.org/gm/document-1.9.34527/13.pdf

- B. Fayissa and C. Nsiah, “The Impact of Remittances on Economic Growth and Development in Africa,” American Economist, Vol. 55, No. 2, 2010, 19 Pages.

- A. K. Fosu, “The Impact of External Debt on Economic Growth in Sub-Saharan Africa,” Journal of Economic Development, Vol. 21, No. 1, 1996, pp. 93-108.

- B. Clements, R. Bhattacharya and T. Q. Nguyen, “External Debt, Public Investment, and Growth in Low-Income Countries,” IMF Working Paper WP/03/249, 2003. http://www.mafhoum.com/press6/176E15.pdf

- C. Patillo, H. Poirson and L. Ricci, “External Debt and Growth,” Review of Economics and Institutions, Vol. 2, No. 3, 2011. http://www.rei.unipg.it/rei/article/view/45

- C. Burnside and D. Dollar, “Aid, Policies and Growth,” American Economic Review, Vol. 90, No. 4, 2000, pp. 847-868. http://www.jstor.org/discover/10.2307/117311?uid=2620192&uid=3738016&uid=2620184&uid=2&uid=3&uid=67&uid=62&uid=5909928&sid=21103227878283 http://dx.doi.org/10.1257/aer.90.4.847

- R. Almeida and A. Fernandes, “Openness and Technological Innovations in Developing Countries: Evidence from Firm-Level Surveys,” Journal of Development Studies, Vol. 44, No. 5, 2008, pp. 701-727. http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/00220380802009217 http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00220380802009217

- M. Schiff and Y. Wang, “North-South and South-South Trade-Related Technology Diffusion: How Important Are They in Improving TFP Growth?” Journal of Development Studies, Vol. 44, No. 1, 2008, pp. 49-59. http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/00220380701722282#.UrB7I_TuJc4 http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00220380701722282

- D. Herzer and O. Morrissey, “The Long-Run Effect of Aid on Domestic Output,” University of Nottingham Discussion Papers, CREDIT Research Papers, No. 09/01, Nottingham, 2010, p. 42. http://www.nottingham.ac.uk/credit/documents/papers/09-01.pdf

- M. Carkovic and R. Levine, “Does Foreign Direct Investment Accelerate Economic Growth?” In: T. H. Moran, E. M. Graham and M. Blomstrom, Eds., Does Foreign Direct Investment Accelerate Economic Growth, Institute for International Economics and Center for Global Development, Washington DC, 2005, pp. 195-220. http://www.iie.com/publications/chapters_preview/3810/08iie3810.pdf

- A. B. Ayanwale, “FDI and Economic Growth: Evidence from Nigeria,” AERC Research Paper 165, African Economic Research Consortium, Nairobi, 2007. http://opendocs.ids.ac.uk/opendocs/bitstream/item/2943/RP%20165.pdf?sequence=1

- A. Sukar, S. Ahmed and S. Hassan, “The Effects of Foreign Direct Investment on Economic Growth: The Case of Sub-Sahara Africa,” Southwestern Economic Review, 2007. http://www.cis.wtamu.edu/home/index.php/swer/article/viewFile/54/48

- J. M. Frimpong and E. F. Oteng-Abayie, “Bivariate Causality Analysis between FDI Inflows and Economic Growth in Ghana,” International Research Journal of Finance & Economics, Vol. 15, 2008. http://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/351/1/MPRA_paper_351.pdf

- G. De Vita and K. Kyaw, “Growth Effects of FDI and Portfolio Investment Flows to Developing Countries: A Disaggregated Analysis by Income Levels,” Applied Economics Letters, Vol. 16, No. 3, 2009, pp. 277-283. http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/13504850601018437#.UrBsWfTuJc4 http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13504850601018437

- J. Brambila-Macias, I. Massa and V. Murinde, “CrossBorder Bank Lending versus FDI in Africa’s Growth Story,” Applied Financial Economics, Vol. 21, No. 16, 2011, pp. 1205-1213. http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/09603107.2011.566179 http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09603107.2011.566179

- G. A. Ella, “Impact of International Income, Prices and Monetary Shocks on Real Exchange Rate in Eight African Economies: An Empirical Study,” The Empirical Econometrics and Quantitative Economics Letters, Vol. 2, No. 3, 2013, pp. 41-54. http://www.jyoungeconomist.com/images/stories/05_EEQEL_V2_N3_September_2013_pp_41_54_Assoumou_Ella.pdf

- D. E. Thomas and R. Grosse, “Country-of-Origin Determinants of Foreign Direct Investment in an Emerging Market: The Case of Mexico,” Journal of International Management, Vol. 7, No. 1, 2001, pp. 59-79. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1075425300000405 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1075-4253(00)00040-5

- W. Naudé and A. Saayman, “Determinants of Tourist Arrivals in Africa: A Panel Data Regression Analysis,” Tourism Economics, Vol. 11, No. 3, 2005, pp. 365-391. http://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/16479/

- R. H. Adams Jr. and H. Richard, “The Demographic, Economic and Financial Determinants of International Remittances in Developing Countries,” World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 4583, 2008. http://www-wds.worldbank.org/servlet/WDSContentServer/WDSP/IB/2008/03/31/000158349_20080331082542/Rendered/PDF/wps4583.pdf

- A. Aslan, F. Kula and M. Kaplan, “International Tourism Demand for Turkey: A Dynamic Panel Data Approach” Research Journal of International Studies, No. 9, 2009, pp. 65-73. http://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/10601/1/International_Tourism_Demand_for_Turkey_A_Dynamic_Panel_Data_Approach.pdf

- M. Calì and S. Dell’Erba, “The Global Financial Crisis and Remittances: What Past Evidence Suggests?” Overseas Development Institute Working Paper 303, 2009. http://www.odi.org.uk/sites/odi.org.uk/files/odi-assets/publications-opinion-files/4408.pdf

- E. Dabla-Norris, C. Minoiu and L. F. Zanna, “Business Cycle Fluctuations, Large Shocks, and Development Aid: New Evidence,” IMF Working Paper WP/10/240, 2010. http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2010/wp10240.pdf

- R. Jan Singh, M. Haacker and K. W. Lee, “Determinants and Macroeconomic Impact of Remittances in Sub-Saharan Africa,” Journal of African Economies, Vol. 20, No. 2, 2011, pp. 312-340. http://jae.oxfordjournals.org/content/20/2/312.short http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/jae/ejq039

- N. Berman and P. Martin, “The Vulnerability of SubSaharan Africa to the Financial Crisis: The Case of Trade,” IMF Economic Review, Vol. 60, No. 3, 2012, pp. 329-364. http://www.palgrave-journals.com/imfer/journal/v60/n3/full/imfer201213a.html

- A. Ugur, “Import and Economic Growth in Turkey: Evidence from Multivariate VAR Analysis,” East-West Journal of Economics and Business, Vol. 11, No. 1-2, 2008, pp. 54-75. http://www.u-picardie.fr/eastwest/fichiers/art68.pdf

- H. Cetintas and S. Barisik, “Export, Import and Economic Growth: The Case of Transition Economies,” Transition Studies Review, Vol. 15, No. 4, 2009, pp. 636-649. http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs11300-008-0043-0/fulltext.html http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11300-008-0043-0

- S. Ullah, Bedi-uz-Zaman, M. Farooq and A. Javid, “Cointegration and Causality between Exports and Economic Growth in Pakistan,” European Journal of Social Sciences, Vol. 10, No. 2, 2009, pp. 262-272.

- C. Woodruff and R. M. Zenteno, “Remittances and Micro Enterprises in Mexico,” Graduate School of International Relations and Pacific Studies Working Paper (Unpublished, University of California, and ITESM, San Diego), 2004.

- D. Yang, “International Migration, Human Capital, and Entrepreneurship: Evidence from Philippine Migrants’ Exchange Rate Shocks,” The Economic Journal, Vol. 118, No. 528, 2008, pp. 591-630. http://www-personal.umich.edu/~deanyang/papers/yang_migshock.pdf http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0297.2008.02134.x

- H. Rapoport and F. Docquier, “The Economics of Migrants’ Remittances,” IZA Discussion Paper 2139, Bonn, 2005. http://ftp.iza.org/dp1531.pdf

- O. Stark and D. Levhari, “On Migration and Risk in LDCs,” Economic Development and Cultural Change, Vol. 31, No. 1, 1982, pp. 191-196. http://www.jstor.org/discover/10.2307/1153650?uid=2620192&uid=3738016&uid=2620184&uid=2&uid=3&uid=67&uid=62&uid=5909928&sid=21103228302963 http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/451312

- D. Ahlburg, “Remittances and Their Impact’, A Study of Tonga and Western Samoa,” Pacific Policy Paper No.7, the Australian National University, Canberra, 1991.

- R. Chami, C. Fullenkamp and S. Jahjah, “Are Immigrant Remittance Flows a Source of Capital for Development?” IMF Staff Papers, Vol. 52, No. 1, 2005, pp. 55-81. http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2003/wp03189.pdf

- C. Amuedo-Dorantes and S. Pozo, “Workers’ Remittances and the Real Exchange Rate: A Paradox of Gifts,” World Development, Vol. 32, No. 8, 2004, pp. 1407-1417. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0305750X04000762 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2004.02.004

- J. Madeley, “Transnational Corporations and Developing Countries: Big Business, Poor Peoples,” The ACP-EU Courier, No. 196, 2003, pp. 36-38. http://ec.europa.eu/development/body/publications/courier/courier196/en/en_036_ni.pdf