Paper Menu >>

Journal Menu >>

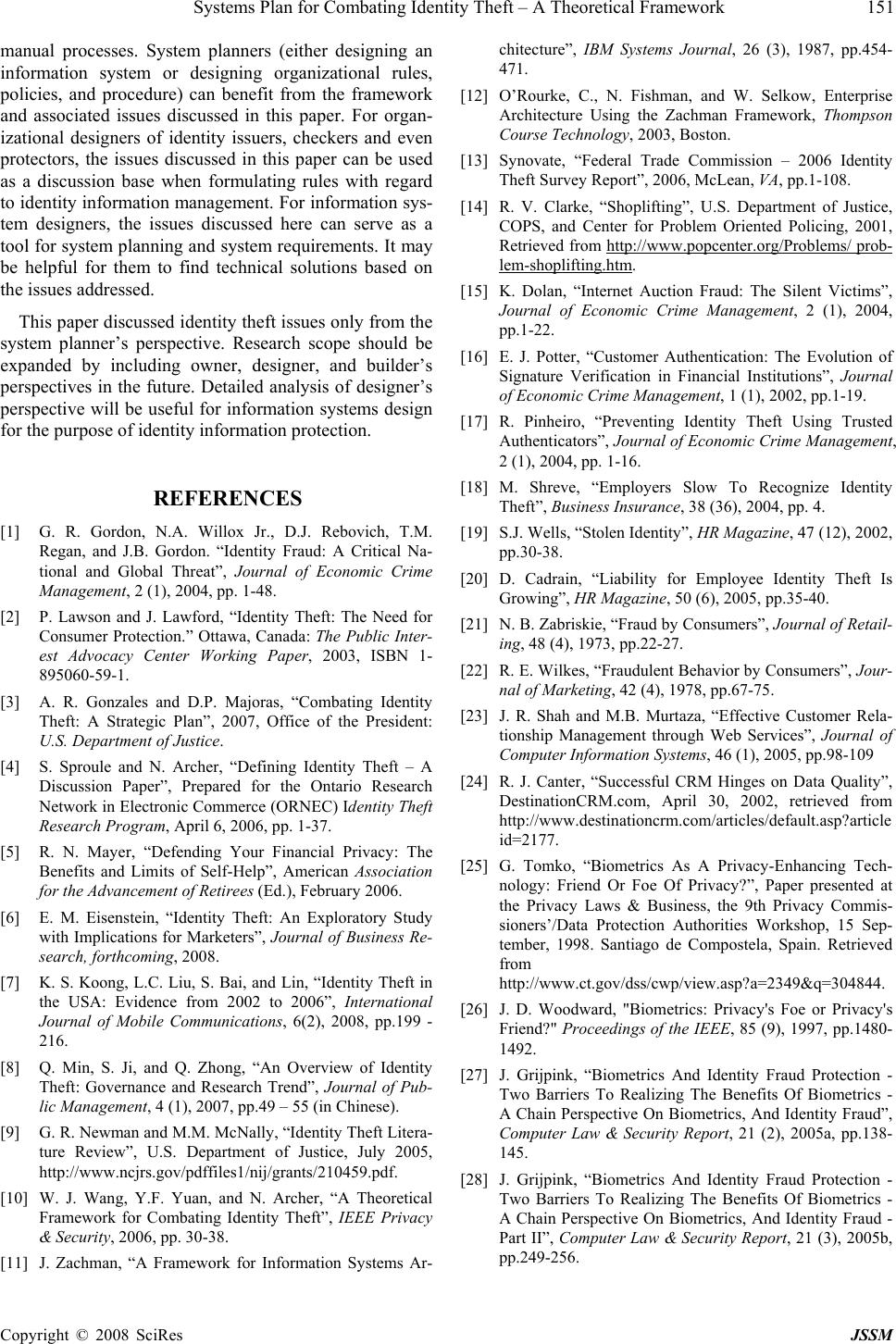

J. Serv. Sci. & Management, 2008, 1: 143-152 Published Online August 2008 in SciRes (www.SRPublishing.org/journal/jssm) Copyright © 2008 SciRes JSSM Systems Plan for Combating Identity Theft – A Theoretical Framework* Shao-Bo Ji1, 2, Shawn Smith-Chao1& Qing-Fei Min2 1Sprott School of Business, Carleton University, Ottawa, ON, Canada K1S 5B6 2School of Management, Dalian University of Technology, Dalian 116024, Liaoning, China E-mail: sji@business.carleton.ca ABSTRACT The Internet has made it easier for individuals and organizations to communicate and conduct business online. At the same time, personal, commercial, and government information has become a target for identity theft. The incidences of identity theft have increased substantially in the Internet age. Increasing news reports of bank/credit cards theft, as- sumed identity for economical and criminal activities has created a growing concern for individuals, businesses, and governments. As a result, it’s become an important and urgent task for us to find managerial and technical solutions to combat identity fraud and theft. Solutions to identity theft problem must deal with multiple parties and coordinated ef- forts must be made among concerned parties. This paper is to provide a comprehensive view of identity theft issue from system planner’s perspective. The roles of identity owner, issuer, checker, and protector, are examined to provide a starting point for organizational and information systems design. Keywords: identity theft, information system plan, inter-organizational coordination 1. Introduction Identify theft problem has been one of the major concerns for individuals, businesses, and governments in the Inter- net age. Businesses and governments have been trying to find solutions through legislations, law enforcement, and new technologies. In academic community, the research into the issue of identity management is gen erally lacking. Most researches have been focusing on technological and/or legal issues. Those researches have dealt with the identity problem from an operational and narrowed per- spective, rather than conceptual and systematic viewpoint [1, 2]. Identity theft is “…the misuse of another individual’s personal information to commit fraud” [3]. Within re- search community, there seems to be no consensus of what identity theft is. For example, Sproule and Archer [4] gave one of the definitions for identity theft as “crimes involving use of a real person’s identity”. Others define identity theft as “false identifiers, false or fraudulent documents, or a stolen identity in the commission of a crime” [1] and as “the unauthorized collection and fraudulent use of someone else’s personal information” [2]. For the purpose of this paper, the definition suggested in [3] is adopted. The seriousness of identity theft is difficult to deter- mine, since the crime may be undetected for a long period of time, and there is no one centralized database for iden- tity theft. Anecdotal evidences an d statistics d rawn from a number of sources do indicate, however, that the problem is growing in many parts of the world, particularly in North American, i.e., United States and Canada, and the problem has quickly become a global phenomenon (see for example reports at www.ftc.gov and www.rcmp.ca as well as the recently released The President’s Identity Theft Task Force’s Report [3]). Consequently, tremen- dous efforts have been made over the past decade by gov- ernments, businesses, and academic research community of various disciplines to understand the issues and to find solutions for combating the problems from the aspects of social and technological, legislative and law enforcement, and business and management. As a result, a number of comprehensive research framework, model, and practical solution have been proposed and the results of the re- search initiatives are emerging [3, 4, 5, 6, 7]. In develop- ing countries such as China, although there is a lack of official statistics, over the past decade, the amount of identity theft related reports, such as cell-phone short messages fraud and fake identity cards and seals, has been on the rise significantly due to the wide spread use of the Internet and mobile devices such as the cell-phone [8]. A comprehensive literature review in identity theft research can be found in Newman and McNally [9]. Identity thieves use a number of techniques to acquire data from individuals. Unsophisticated, but effective tech- *This study is funded by Ontario Research Network for Electronic Comm erce (ORNEC), Ontario, Canada.  144 Shao-bo Ji, Shawn Smith-Chao & Qing-fei Min Copyright © 2008 SciRes JSSM niques include the theft of wallets, cell-phone, and lap- tops. Credit card statements or other documents can be taken from trash or intercepted in the mail. One of the most effective means of theft is called “Social Engineer- ing”, which involves the thief contacting the victim di- rectly, and convincing them to disclose passwords or other information by posing as agents of ID issuing agen- cies. Victims are also targeted over the Internet, through social engineering by email message or by intercepting and capturing financial or identity information while it is being transferred online. The information of a large num- ber of individuals can be captured at one time by hacking into and stealing data from financial or government data- bases, a crime which has drawn significant media atten- tion. In China, due to the lack of individual’s privacy concerns and the lack of mechanisms of public protection, the situations seem to be more serious. For instance, many such individual’s information as name, date of birth, identity card number, and cell-phone number are openly published in the public domain such as the Internet, post- ers, and internal documentations. Combating identity theft requ ires actions fro m multiple parties. It requires technological, legal and law enforce- ment, economical, and managerial solutions. Solving identity theft problem must deal with multiple parties and coordination among the parties since the confirmation of individual’s identity often involves multiple steps, multi- ple methods, and with multiple parties. This is especially important in the virtual environment where the verifica- tion, validation, and authentication of identity are con- ducted online and virtually no face-to-face identity con- firmation. To this end, the US government has taken a major step in dealing with the issue. The President’s Iden- tity Theft Task Force’s Report entitled “Combating Iden- tity Theft: A Strategic Plan” is an important blueprint that guides government agencies, businesses, and individuals to combating identity theft [3]. Released in April 2007, the report not only describes and summarizes the identity theft stages and sequences but also, more importantly, recommends and proposes an important strategy from the perspective of id entity theft prevention, con sumer protec- tion, and law enforcement. As outlined in the report, the occurrences of identity theft generally take place in three stages: 1) the acquisition of a victim’s personal informa- tion by the identity thief; 2) the attempt of misuse of sto- len information by the identity thief; and 3) the identity thief committed crime and the victims suffer the loss (emotional and/or financial). The reports made a number of recommendations which focus on the four areas: 1) identity theft prevention by keeping individual consumer data safe, in public and private sectors as well as individ- ual consumers, through better data security measure and awareness education; 2) preventing identity thieves from using consumer data to steal individual’s identity through authentication and comprehensive record keeping mecha- nism of private sector use of social security numbers; 3) the creation of assistance program of identity theft; 4) stronger law enforcement through National Identity Theft Law Enforcement Center, better coordination and infor- mation intelligence sharing between law enforcement and private sector, and better coordination with foreign law enforcement. The report provides an excellent starting point for government agencies, private businesses, and consumers in combating identity theft. It is particularly useful for public policy formulation. Similarly, a number of studies have been conducted to address the issue from consumer’s perspective in the financial service sector [5], the policy options in coping with identity theft [6], and the general description and trends in different regions of the US [7]. For example, Mayer investigated “the state of consumer self-protection with respect to financial pri- vacy” [5]. Using content analysis, field experiment, and telephone survey, he identified various advice offered from government, business (nonprofit and for profit or- ganizations), and financial journalists and concluded that consumers are general aware of the problems and they are facing the trade-off between keeping their privacy and spending money in protecting their identity. The study suggested that more efforts are needed for governments and businesses to create an environment that provides consumers efficient methods of protecting their identity. Other studies explored the potential solution for combat- ing identity theft that goes beyond existing recommenda- tions and practices. For example, Eisenstein suggested that “the existing approach to combating identity theft will not work” [6]. Applying system dynamic modeling technique, Eisenstein proposed and tested a model that explained the motivations and actions of various players of identity theft. He concluded and suggested that an “in- expensive security freezes” can be an effective way of reducing identity theft. While aforementioned US government strategic plan and recommendations suggested in various studies are useful in dealing with public policies, understanding the nature of identity theft, and finding solutions in combat- ing identity theft, they are limited in the sense o f cov ering the scope of the issues. More works have yet to be done to implement the recommendations included in the US Strategic Plan. As stated earlier, the nature o f the identity theft is identity thieves’ misuse of another individual’s personal data. As a result, information technology and information systems play a special role in the process. As a powerful tool, information system and associated tech- nologies can be designed in such a way that it can facili- tate the process of combating identity theft. This study complements the US Strategic Plan by providing opera- tional level recommendations from the viewpoint of sys- tems analysis and design. It pays special attention to multi-party coordination in combating identity theft which is strongly recommended by the report. From system analysis and design perspective, under- standing identity theft problem and designing managerial and technological systems to combat identity theft re-  Systems Plan for Combating Identity Theft – A Theoretical Framework 145 Copyright © 2008 SciRes JSSM quires a holistic and comprehensive framework. Specifi- cally, identifying key players and their associated roles and relationships is an important first step. In this aspect, two frameworks are suited for such purpose. The first framework is Wang et al.’s [10] contextual framework for combating identity theft. The second is a framework proposed by Zachman [11]. Wang et al.’s framework identified five main roles involved in the ownership, issu- ance, use, protection, and abuse of identity information. These roles are identity owner, identity issuer, identity checker, identity protector, and identity thief. They are linked by a web of relationships which identify the prin- ciple responsibilities and interactions of the members of the identity verification, validation, and authentication chain. Zachman’s framework defines the interfaces and the integration of all of the components of a system by perspective and aspect. The framework has been applied in many applications and enterprises and has been pro- posed for part of the US government’s internal enterprise architecture [12]. The purpose of this paper is to demonstrate how the Zachman framework can be applied to the conceptual model by Wang et al. [10] to provide a comprehensive and complete view of the iden tity theft problem. 2. Identity Theft Conceptual Framework Preventing identity theft are the responsibilities of many individuals in many organizations. As outlined in Wang et al.’s [10], there are primarily four stakeholders and one aggressor. The focus of identity theft issue is the identity owner, the person the data actually identifies and to whom the identity information and documents are pos- sessed or assigned. The owner’s physical, biographical, psychological, and/or financial data is created and stored on the identity do cument or database. The identity issuer, normally a government institution or financial institution, acquires, creates, and produces these information and documents. When the identity owner wishes to make transactions using th eir identity in formation or documents, they are checked by an identity checker, which is a per- son or device responsible for determining the validity of his/her identity information and documents. From infor- mation processing viewpoint, this process typically go through three stages: verification, validation, and authen- tication. The checker works with the identity issuer, and often these two roles are accomplished in the same or- ganization. For example, banks have their own identity checker to validate the owners of accounts. The identity protector is responsible for determining if the security of the identity chain has been breached, and for prosecuting and punishing identity thieves. The protector works with issuers and the checkers to maintain a vigilant guard, but has a largely post-incident rapport with owners. Finally, the identity thief/abuser is, of course, any party attempt- ing to misuse, copy, or steal the identity own er’s informa- tion or documents. Things Processes C o n n ect iv ity People Timing M o tiv atio n Planner List of important things to the business List of processes business performs List of locations in which the business operates List of business responsibilities List of events significant to the business List of business goals/strategy Owner Semantic model Business process model Logistics network Work flow model Master schedule Business plan Designer Logical data model Application architecture Distributed system architecture Human interface architecture Processing structure Business rule model Builder Physical data model System design Configuratio n design Presentation architecture Control structure Rule design Subcontractor Data definition Program Network architecture Security architecture Timing definition Rule specification Functioning Enterprise Data Process Network Organization Schedule Strategy Figure 1. Zachman framework of information system architecture  146 Shao-bo Ji, Shawn Smith-Chao & Qing-fei Min Copyright © 2008 SciRes JSSM The importance of such framework is that it identifies the main parties and the interconnections between the various parties. This is critical since many identity theft experts have listed a lack of coordination of relevant par- ties as a key factor in the proliferation of identity theft crime [1]. Coordinated solutions include the use of shared identity databases [1, 15, 16], international laws for iden- tity theft and fraud [1], cohesive national law enforce- ment programs [1, 2], and trusted authenticators [17]. 3. Zachman’s System Framework First published in IBM Systems Journal in 1987, the framework is considered as a “logical construct (or archi- tecture) for defining and controlling the interfaces and the integration of all of the components of a system.” [11] Shown in Figure 1, the framework is composed of a ma- trix of six columns and six rows. The rows represent the main perspectives (of different roles) for viewing and framing the system: planner, owner, designer, builder, subcontractor, and functioning enterprise. The columns represent aspects (of different views) of the system: things, processes, connectivity, people, timing, and moti- vation. For any system design and implementation, various parties are involved. First, the system planner initiates the conceptualization of the system, and then determines its purpose and scope based on system owner’s requests. Then, the system designer, the architect of the system, takes the owner’s requirements for the system and design the system according to the technical and economical feasibility set out by the planner. The builder is responsi- ble for the actual realization and implementation of the system. The builder may employ subcontractors to do the actual construction and assembly of the system. The final result of the process is the functioning enterprise. Each perspective in the framework (other than the functioning enterprise) can be embodied by a person, a group, an or- ganization, or another system. The rows of the system correspond to what (things), how (processes), where (connectivity), who (people), when (timing), and why (motivation), and. Things repre- sent the materials or structures that the system is com- posed of. Processes represent system’s functional specifi- cations. Connectivity shows where the linkages exist in the system and the locations of process flows. People refer to individuals who perform their tasks and assume their responsibility. Timing indicates when events are expected to occur. Motivation refers to the motivating elements of the system such as the purposes and inten- tions of the system owner. The framework provides a tool for us to address main system questions and main per- spectives of all relevant parties. The intersections of each row and column are called artifact and th ey are filled with the relevant diagrams, lists, or structures. Examples of artifacts used when designing systems architecture are shown in Figure 1. An artifact can be modeled in a vari- ety of means, using one or more tools, as long as the con- tents match the purpose of the aspect, and the relevant perspective. 4. A Framework for Identity Theft Issue A complete Zachman’s framework for each identity role and their interactions will require the knowledge of iden- tity management, resources, as well as system and organ- izational system requirements. Detailed analysis of each cells and intersections (6 rows and 6 columns and their intersections) will require a much more lengthy discus- sion. For the purpose of this paper, we focus on the role of system planner. Reviewing the planner’s role for each member of the identity chain addresses many of the key aspects of the identity theft problem, and can be helpful for organizational and system designers to understand system requirements, organization or information, and to manage the identity and to prevent identity theft from occurring. In this section, each role will be explored using system planner’s role. 4.1. Identity Owner The identity owner is the originating source of the iden- tity chain. Though the issuer is responsible for the deter- mination and creation of all identity information and documents, the process requires the existence of an owner to initiate the identity definition process. In a special situation, identity thieves can create the identity informa- tion and docu ments based on a fictitious perso n or a dead person. The source data for the identity information and document often describes the attributes possessed by the identity owner such as age, date of birth, addresses and additional data that are assigned by the identity issuer such as a bank account or identification numbers. Usabil- ity, security, and privacy are typically the main concerns of the owners. These artifacts are somewhat paradoxical, as ease of use is not generally associated with increased security and privacy. Tradeoffs are often required. This however represents a key need for owners, and the re- sponsibility for meeting this need is shared with the issuer. Documents which are cumbersome to hold and use are not attractive. Similarly, documents which are not secure are not attractive. Input from both the owner and issuer is necessary to balance these two concerns. Privacy is a real concern to the owners. Although re- lated to security, privacy indicates the desire for the owner to minimize the exposure of their information to the issuer, and to other members of the identity chain. Issuers have to consider the privacy concerns of owners, they want to maximize the amount of data they collect from owners, to support the needs of their identity infor- mation and documents. Privacy is a key artifact for the owner, and may be a weakest point in the identity chain. In most western countries, some owners’ desire to main- tain privacy will prevent them from entering the chain at all. Addressing the needs of these owners is difficult,  Systems Plan for Combating Identity Theft – A Theoretical Framework 147 Copyright © 2008 SciRes JSSM since suspicion and a lack of trust often prevent the issuer or other identity chain member from making meaningful contact with the owner. The identity protector and infor- mation security technology plays a key role here. The identity owner establishes the identity that will be used and stored in identity database and shown on docu- ments. The owners collaborate with the issuers to create data and documents, and also to update or change data as their personal information change. The creation and up- dating processes are important, as the validity of identity documents rest on their accuracy of the data within. Ex- amining the intersection of things and processes, we see that these processes must be easy, secure, and private for them to fulfill the owners’ needs. To meet these requirements, owners need to use their identity data and documents responsibly and to protect their own information and to report any abuses. Irrespon- sible document use can obviate any security procedures put into place, and place the owner beyond the reach of identity protectors, and even possibly in opposition to them or other members of the identity chain. Unfortu- nately, the fraud detection and reporting process is one of the weakest and least developed processes in the identity chain [9, 13, 14]. Although identity issuers, checkers, and protectors all play roles in this process, the owner can usually detect abuses first. Proper security procedures by the checker and issuer can prevent transgression, however, once they have occurred, they will remain hidden unless until discovered by the owner, often more than a year later [2]. The owner needs to use their identity information and identity documents at a number of locations. Transaction points represent any places (physical or virtual) where an identity owner and identity checker interact. These in- clude retail stores, issuer checkpoints and offices, gov- ernment offices, online buying sites, and even at home. Home as a location has special significance, since this is where identity information and documents are stored. This is a common breach point for criminals who acquire information about the owner and their identity from trash, or theft of mails, or the physical documents [2]. Identity information and documents are also required for work, for verification of identity, or for hiring or human re- source purposes. Work locations and databases are poten- tial areas of threats and point of penetration since these systems are maintained or monitored by fewer and less stringent security systems than identity issuer sites [18]. Employee records are in fact the number one source for identity data for thieves [19]. Increasingly employers have become the targets for legal action, due to improper storage and handling of employee data [20]. Maintaining the security of identity information and documents is one of the two responsibilities (of people) assigned to the owners. This responsibility is shared with identity checkers and identity issuers. However, the pri- mary target for most identity theft is the owner [13]. Ac- cording to one report, over 50% of identity victims know the identity of the person who d efrauded th em [13]. Own- ers should ensure that they maintain physical control of their identity documents as have a strong knowledge of where their identity data is being used and sto red, but for most people this is at best a difficult task. Due to large number of transaction points for identity information and documents used, often people are not aware of the spread of their identity data. The integrity of the identity networks that are built around individuals rests also on the owners presenting truthful and accurate identity data about themselves. When owners lie or falsely present their data, they move beyond the reach of the security procedures of checkers and issuers, and the legal reach of identity protectors. Fraudulent behavior on the part of owners is another area that needs attention for research [21, 22]. Though some identity checks are done by inspection (looking at signa- tures and photo identification), many are done electroni- cally. Electronic checks rely on having consistent data throughout. As discussed later, data dispersion is a key concern for the identity chain process, as this increases the chances of inaccuracies, and improper updates. Cen- tralization of data simplifies both the checking process, and decreases the number of inaccuracies, leading to drastic improvements in the costs of managing customer data [23, 24]. The motivations of the identity owner are straightfor- ward. Owners want to be able to use their tran saction d ata, while maintaining the security of their identity informa- tion. An identity co ntrol and use process that can add ress and improve both concerns would be optimal. Develop- ments in biometrics technologies may facilitate the ability for owners to safely use their identity data an d documents. Work in this field has encountered a great deal of resis- tance due to privacy concerns by groups and individuals [25, 26]. Proposed solutions must allay these fears with- out compromising the distinct advantages of biometric identification. It must be realized, however, that even biometric solutions are not foolproof, unless care is taken to maintain security of biometric data, and cooperation among the identity chain members [27, 28, 29]. 4.2. Identity Issuer Identity issuer is the force behind the identity process. Government agencies, financial institutions, employers, retailers, and professional organizations create identity information and documents. The information and docu- ments are often critical or even central to their businesses. Credit card companies for example thrive on the transac- tions made with their cards. Banks maintain and operate financial accounts for owners, drawing income from fees and investments. Governments are mandated with provid- ing services that require identification, and track indi- viduals for the purposes of security and taxation.  148 Shao-bo Ji, Shawn Smith-Chao & Qing-fei Min Copyright © 2008 SciRes JSSM The identity issuer must guard the interests of owners. They need to coo rdinate with identity pro tectors to en sure the security of the data. Although the identity issuers have a number of unique artifacts, they share a substantial number with other members of the identity chain. Issuers hold the reposito ries for identity data and create identity documents. They support their businesses by en- suring that transactions are secure and that any losses to themselves or other members are minimized. Credibility is a key artifact with respect to issuers concerns. Owners that do not h ave faith in the security of their identity data will abandon the use of the issuer’s documents [30, 31]. In addition, identity checkers that find the verification process cumbersome or insecure may not recognize or accept the identity documents. Identity issuers handle a number o f p rocesses related to their documents and the owners’ data. They produce the documents themselves and often create the identifiers used in transactions with the documents. Maintaining, updating, and altering identity data is also done by the issuers. Issuers are also a likely party to find abusers, by examining data looking for suspect transactions, and by tracking bad verification attempts. Issuers are also part- ners with identity protection services, working to protect other identity chain members. An important but overlooked process for issuers is the responsible use of identity documents. Particularly for governments and financial bureaus, a call has been made to clarify what these organizations can and are allowed to do with the data they control [32, 33, 34, 35]. Examining the overlap between things and processes, it can be seen that the desire to increase revenue, minimize loss, and exposure must be balanced against credibility issues. Revenues can often be increased by issuers by distribut- ing the information they hold to third parties. They can also attempt to minimize loss by coordinating and distrib- uting data with checkers and protectors. For example, verification through biometric identifiers or cross valida- tion through multiple identifiers can improve the chances that the issuer or checker cannot be the victim of fraud, but this puts the owner at risk, which is exposing greater and more sensitive data in ord er to verify their identity. Though owners may use identity documents at a num- ber of transaction points, the creation, verification, and update of these documents occurs at branches of the issu- ing organization. Though the contact may be physical or virtual, all transaction will flow through these nodes. Even identity checking is done by contacting the onsite databases of the issuing organization. This allows the issuer to ensure that validation procedures are consistent, and that validation data is centralized. Centralization and con sistency fit with the issuer’s ro le of safeguarding identity data. Although owners are the custodians of the actual identity documents, identity data security is shared by both owners and issuers. Other document processes, such as creation, maintenance, and destruction are handled exclusively by issuers. Maintenance tasks include updating identity data, re- placing damaged, lost, or stolen identity documents. Document destruction may be in response to theft at- tempts, or if the owner no longer wishes to interact with a particular user. Institutional and government issuers may also require document destruction if the personal leaves their jurisdictional realm or due to death. The topic of document maintenance and destruction and its impact on the identity cycle has not been extensively researched, however the media has addressed the issue [36]. The issuer is the most frequent contact with identity data and documents, due to their control of the actual data repositories, and the necessity for use of this data for up- date, verification, and creation events. Issuers are also the first contacts with owners who are seeking identity docu- ments. This particular event is relevant, as the actual vali- dation and assertion of the identity of an owner occurs at this time. Errors in collection of identity data, or success- ful fraud on the part of the owner can create an inaccurate identity, which can have a long-term impact on all further transactions. Often identity documents are validated based on other identity documents are data. Errors can compound, and allow identity thieves to breach security processes. With the creation o f a sing le identity d ocument (called a breeder document, an identity thief can spawn numerous other documents, solidifying their fraudulent identity. The longer the chain that is spawned, the more difficult it may be to detect the origin al error or fraud [1]. The motivations of identity issuers vary based on the na- ture of the organization. Institutional and governmental bodies require identity documents to identify and track individuals. Documents of this type include birth certificates, driving licenses, health service cards, and passports. These documents may or may not have attached services or privileges. These documents are the most common breeder documents as the institutional weight adds credibility to the identity document. This is also why these are the documents of choice for identity thieves, as a successful intrusion in this early stage enables a large number of other docu- ments to be obtained [1]. Fraudulent documents that are not institutional are more easily detected , as they lack the necessary and often required supporting documentation. This is why the Internet crime has proliferated, as it en- ables criminals to secure non-institutional documents and use them without supporting institutional data. Validation using this data can help curb this type of fraud and theft. Biometric identification can also act as a strong deterrent to online crime, but this has not been implemented exten- sively online at this time. Non-institutional issuers generally operate to support their businesses, and often for financial gain. Identity documents of this type include credit cards, bank transac-  Systems Plan for Combating Identity Theft – A Theoretical Framework 149 Copyright © 2008 SciRes JSSM tion documents (cards and books), membership cards, and frequent transaction cards. Documents of this type usually have an attached service or privilege, and often incur fees for use. Though these documents offer benefits for users to attract adoption, the primary purpose of these docu- ments is for the financial gain of the issuer. As such, the credibility and security of these documents is a key con- cern for the issuer. The issuer often suffers monetary or credibility loss if a breach is successful. For this reason the issuer will often employ identity protectors them- selves rather than relying on institutional p rotectors. It’s worthwhile to mention here is the fact that many western countries such as Canada and UK, as a result of 9/11, have started examining the issue of creating na- tional identity card. For example, the British government passed the British Identity Cards Act in 2006 [39]. It will help government to better manage the identity data. At the same time, the implementation of th e Act raised many concerns due to potential misuse and privacy breaches. Other countries such as Canada abandoned the suggestion of creating national identity database due to its citizen’s privacy concerns. 4.3. Identity Checker The identity checker locates at the central point of the identity chain. They process transactions using the iden- tity owner’s data and documents, and verifying their au- thenticity with the identity issuer. The identity checker, however, is the party with low incentives to work with the other identity chain members. In most cases, they have little to gain by accepting greater responsibility. However, identity checker is actu ally the party best suited for preventing fraud and theft. Identity checker is mainly motivated by financial gain in case of commercial organizations, or protection of fi- nancial loss and prevention of crimes in case of govern- ment agencies. Owners use their identity information and documents to obtain goods and services from the identity checker, who uses information to establish identity, and to process the payments. It is certainly in checker’s best interest to ensure the credib ility of its tran saction pro cess, and to guarantee th e security of the o wner’s identity. This conflict of motivation leads to a central conflict in the identity chain. For example, databases are critical to al- low retailers to respond to customer needs. These data- bases contain identity data about their customers, some of which is collected without the knowledge or explicit con- sent of owners. The data is a prime target for thieves, as these data- bases are a far more efficient means of collectin g identity data than targeting owners directly. The identities of the customers can be accessed from a single database. Iden- tity thieves often have access identity information within checker’s organizations since they know the existing se- curity protocols or lack thereof. Until recently, incentives do not exist for identity checker organizations to monitor their employees. However, the introduction of the recent legislation makes businesses liable for losses from em- ployee theft or careless safeguardin g of iden tity data [20]. It is therefore critical that checkers consider their role as a guardian. Checkers who are focused solely on material gains will overlook the necessity of this role, and may even actively sell identity data to the third parties. They may also be less careful in their processing procedures of identify data. Verification procedures often require confirmation from secondary identity sources, a process that is often ignored by checkers who are not motivated to follow these procedures, with a few exceptions such as credit card transaction. Additionally, identity documents often can only verify that the person who is h olding the iden tity document is who they say they are. It cannot be used to validate the actual righ ts of the ho lder with respect to the issuer [1]. Possessing a forged document can allow an identity thief to get approval with respect to identity checkers, since the biometric data will seem to be correct. Checkers and issuers must still be careful to ensure th at the identity document holder can actually be validated as a recognized recipient of the benefits conferred by pos- sessing the document [37]. This is a key issue with re- spect to future identity theft proposals. The early detection of a thief can prevent loss to the owner or issuer. Issuers often require patterns of transac- tions to identify thieves, or the commission of a starkly inappropriate transaction. Smart thieves however can elude these means of detection. The issuer relies heavily on owners and checkers to report crimes, but both parties have low reporting rates [13, 38]. 4.4. Identity Protector The identity protector is an important member, typically with certain authority and power, of the identity chain. The protectors may often interact with issuers and with owners, and even checkers, their responsibilities and processes are unique. The motivations of the protectors are not directly related to the transaction processes, and the existence of the protector role relies on the existence of identity fraud and theft. Protectors are generally the last party to have a presence in a particular transaction chain, or identity issue. They maintain lists of offenders and complaints, and use these to investigate abuses. They also compile statistics which can be used to gauge which transaction points, methods, and documents are most at risk for intrusion by thieves. Where possible, protectors will prosecute offenders, or will at least create incident reports that can be tracked for future use. In addition to the reactive processes, they also develop methods to detect identity fraud and theft and they create legislation which can be enforced. Although identity theft is not a new crime, its proliferation on the Internet is a recent development. The protector role is evolving, and  150 Shao-bo Ji, Shawn Smith-Chao & Qing-fei Min Copyright © 2008 SciRes JSSM has been criticized as being indifferent in the past. Iden- tity checkers were also ambivalent since the costs were passed on to the issu er or the own er. There was v ery little protection afforded to identity owners, since the identity issuer would often make it difficult for the owner to re- coup their losses. The introduction of Identity Theft Fed- eral Law in the United States and subsequent other laws have rectified many of these issues, giving owners more protection, issuers more responsibility, and protectors the legal basis to prosecute thieves [9 , 35]. Still, many crimes are not reported. This makes protectors at a difficult situa- tion. Issuers and checkers often do not report crimes and losses, fearing it may tarnish their credibility. Instead they deal with the theft as a “cost of doing business” [14]. Owners themselves are often to blame, as only 26% of owners report incidents to the police [13]. One of the greatest challenges in the legal arena is that the Internet is global, and therefore requires global laws and global protectors. At this time, such agencies and laws are not in place. A comprehensive system of global laws and a policing agency with global jurisdiction will be required to successfully cu rb and co ntrol iden tity fraud and theft in the future [1]. Protectors enter the transaction chain usually when the owner or issuer contacts them. It is possible that protec- tors may be employed by issuers, and also be located at issuer sites. The protectors are also likely to be monitor- ing actual transaction points, looking for abuses. In gen- eral however, owners or issuers bring their problems to protectors who then act upon that information. The identity protector has a nu mber of important roles. Most protectors use passive protection. Though the pro- tector will produce materials that attempt to assist the owner in the protection of the identity, they will not take action with regards to a particular owner’s plight until they are notified that something has gone wrong. Active protectors will take actions to prevent identity theft or fraud from occurring, and may actually review and ob- serve transaction points to determine if underlying trans- action patterns are suspicio us. Active protectors will often contact the owner first, querying their transaction activi- ties, and warning owners of potential identity security breaches. The passive type of protector is associated with gov- ernmental and judicial agencies which have the potential to access data within large jurisdictions, but do not have a business or legal framework with wh ich they can actively pursue issues. Privacy concerns of individuals are main concern in this respect. Although government agencies may have nearly unlimited access to owner identity data, access to that data must be justified within a strict legal framework. Passive identity protectors are opposed by other types of protectors including privacy protectors, and government watchdog groups. Finally, as governmental or judicial agencies supported by taxpayer funds or dona- tions, passive protectors do not have established business models that bring returns based on the quality or vigi- lance of their protection. Active protectors however, are usually in the employ of the identity issuer or possibly identity checker. These groups work to prevent breaches in the security measures of the established identity chain, and to seal these breaches as quickly as possible. They will monitor previ- ous and possible even live transactions, looking for pat- terns that might indicate fraud or theft. They will also contact owners directly, when anomalies are detected, or if certain transaction thresholds are reached. Active protectors have a very different perspective and orientation, as the success of the endeavors will often save their employers and benefactors from financial or reputation loss. An important difference between passive and active protectors is those active protectors usually work in the best interests o f the issuer rather than passive protectors who work in the best interests of the owner. Active protectors will therefore often investigate owner issues, including po tential misuse or error of id entity data or documents. Passive protectors will only become in- volved in these cases based on legal infraction. Active and passive protectors do work together how- ever, to fulfill additional protector roles. Passive protec- tors are responsible for law development and enforcement. They make laws to protect other members of the identity chain. They also determine punishments for offenders and carry out the enforcement process. Passive protectors rely heavily on active protectors in the execution of these re- sponsibilities, and active protectors provide evidence used in the prosecution of offenders. Active protectors also provide information and advice to passive protectors who then covert this into policy and law. The role is not one-sided however as passive protectors ensure that there is a balance between the interests of issuers, checkers, and owners. They also provide a voice for owners, when the protection system fails them, and owners find them- selves in opposition to active protectors. 5. Conclusions The importance of Wang et al.’s and Zachman’s frame- works for system planning to combat iden tity theft is that it provides a comprehensive view of various roles and their relationships in the identity chain. We believe that combating identity theft will requ ire coor dinatio n o f id en- tity owner, issuer, checker, and protector. We hope our work will provide a starting point for organization and system designers to include and consider issues relating to identity theft when designing its systems. Specifically, we believe that it’s necessary for owners, issuers, check- ers, and protectors to collaborate. The system must be designed to facilitate the collaborations. With the devel- opment of information and communication technologies, many of the collaborative tasks can be automated. Some tasks, however, must rely on human interventions and  Systems Plan for Combating Identity Theft – A Theoretical Framework 151 Copyright © 2008 SciRes JSSM manual processes. System planners (either designing an information system or designing organizational rules, policies, and procedure) can benefit from the framework and associated issues discussed in this paper. For organ- izational designers of identity issuers, checkers and even protectors, the issues discussed in this paper can be used as a discussion base when formulating rules with regard to identity information management. For information sys- tem designers, the issues discussed here can serve as a tool for system planning and system requirements. It may be helpful for them to find technical solutions based on the issues addressed. This paper discussed id entity theft issues only from the system planner’s perspective. Research scope should be expanded by including owner, designer, and builder’s perspectives in the future. Detailed analysis of designer’s perspective will be useful for information systems design for the purpose of identity information protectio n. REFERENCES [1] G. R. Gordon, N.A. Willox Jr., D.J. Rebovich, T.M. Regan, and J.B. Gordon. “Identity Fraud: A Critical Na- tional and Global Threat”, Journal of Economic Crime Management, 2 (1), 2004, pp. 1-48. [2] P. Lawson and J. Lawford, “Identity Theft: The Need for Consumer Protection.” Ottawa, Canada: The Public Inter- est Advocacy Center Working Paper, 2003, ISBN 1- 895060-59-1. [3] A. R. Gonzales and D.P. Majoras, “Combating Identity Theft: A Strategic Plan”, 2007, Office of the President: U.S. Department of Justice. [4] S. Sproule and N. Archer, “Defining Identity Theft – A Discussion Paper”, Prepared for the Ontario Research Network in Electronic Commerce (ORNEC) Identity Theft Research Program, April 6, 2006, pp. 1-37. [5] R. N. Mayer, “Defending Your Financial Privacy: The Benefits and Limits of Self-Help”, American Association for the Advancement of Retirees (Ed.), February 2006. [6] E. M. Eisenstein, “Identity Theft: An Exploratory Study with Implications for Marketers”, Journal of Business Re- search, forthcoming, 2008. [7] K. S. Koong, L.C. Liu, S. Bai, and Lin, “Identity Theft in the USA: Evidence from 2002 to 2006”, International Journal of Mobile Communications, 6(2), 2008, pp.199 - 216. [8] Q. Min, S. Ji, and Q. Zhong, “An Overview of Identity Theft: Governance and Research Trend”, Journal of Pub- lic Management, 4 (1), 2007, pp.49 – 55 (in Chinese). [9] G. R. Newman and M.M. McNally, “Identity Theft Litera- ture Review”, U.S. Department of Justice, July 2005, http://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/nij/grants/210459.pdf. [10] W. J. Wang, Y.F. Yuan, and N. Archer, “A Theoretical Framework for Combating Identity Theft”, IEEE Privacy & Security, 2006, pp. 30-38. [11] J. Zachman, “A Framework for Information Systems Ar- chitecture”, IBM Systems Journal, 26 (3), 1987, pp.454- 471. [12] O’Rourke, C., N. Fishman, and W. Selkow, Enterprise Architecture Using the Zachman Framework, Thompson Course Technology, 2003, Boston. [13] Synovate, “Federal Trade Commission – 2006 Identity Theft Survey Report”, 2006, McLean, VA, pp.1-108. [14] R. V. Clarke, “Shoplifting”, U.S. Department of Justice, COPS, and Center for Problem Oriented Policing, 2001, Retrieved from http://www.popcenter.org/Problems/ prob- lem-shoplifting.htm. [15] K. Dolan, “Internet Auction Fraud: The Silent Victims”, Journal of Economic Crime Management, 2 (1), 2004, pp.1-22. [16] E. J. Potter, “Customer Authentication: The Evolution of Signature Verification in Financial Institutions”, Journal of Economic Crime Management, 1 (1), 2002, pp.1-19. [17] R. Pinheiro, “Preventing Identity Theft Using Trusted Authenticators”, Journal of Economic Crime Management, 2 (1), 2004, pp. 1-16. [18] M. Shreve, “Employers Slow To Recognize Identity Theft”, Business Insurance, 38 (36), 2004, pp. 4. [19] S.J. Wells, “Stolen Identity”, HR Magazine, 47 (12), 2002, pp.30-38. [20] D. Cadrain, “Liability for Employee Identity Theft Is Growing”, HR Magazine, 50 (6), 2005, pp.35-40. [21] N. B. Zabriskie, “Fraud by Consumers”, Journal of Retail- ing, 48 (4), 1973, pp.22-27. [22] R. E. Wilkes, “Fraudulent Behavior by Consumers”, Jour- nal of Marketing, 42 (4), 1978, pp.67-75. [23] J. R. Shah and M.B. Murtaza, “Effective Customer Rela- tionship Management through Web Services”, Journal of Computer Information Systems, 46 (1), 2005, pp.98-109 [24] R. J. Canter, “Successful CRM Hinges on Data Quality”, DestinationCRM.com, April 30, 2002, retrieved from http://www.destinationcrm.com/articles/default.asp?article id=2177. [25] G. Tomko, “Biometrics As A Privacy-Enhancing Tech- nology: Friend Or Foe Of Privacy?”, Paper presented at the Privacy Laws & Business, the 9th Privacy Commis- sioners’/Data Protection Authorities Workshop, 15 Sep- tember, 1998. Santiago de Compostela, Spain. Retrieved from http://www.ct.gov/dss/cwp/view.asp?a=2349&q=304844. [26] J. D. Woodward, "Biometrics: Privacy's Foe or Privacy's Friend?" Proceedings of the IEEE, 85 (9), 1997, pp.1480- 1492. [27] J. Grijpink, “Biometrics And Identity Fraud Protection - Two Barriers To Realizing The Benefits Of Biometrics - A Chain Perspective On Biometrics, And Identity Fraud”, Computer Law & Security Report, 21 (2), 2005a, pp.138- 145. [28] J. Grijpink, “Biometrics And Identity Fraud Protection - Two Barriers To Realizing The Benefits Of Biometrics - A Chain Perspective On Biometrics, And Identity Fraud - Part II”, Computer Law & Security Report, 21 (3), 2005b, pp.249-256.  152 Shao-bo Ji, Shawn Smith-Chao & Qing-fei Min Copyright © 2008 SciRes JSSM [29] Computer Weekly, “Biometrics Accuracy Will Depend on Registration”, Computer Weekly, 2/10/2004, pp.26. [30] Verisign, “White Paper: The Merchant Supply Chain – Dangers, Challenges, and Solutions”, 05/20/2005, http://www.verisign.com/static/005292.pdf. [31] R. Behar, “Never Heard Of Acxiom? Chances Are It's Heard Of You”, Fortune, 2/23/2004, 149 (4), pp. 140-148. [32] S.H. Wildstrom, “Your Data, Naked on the Net”, Business Week Online, 2/9/2006, pp.20. [33] D. Gillin, “The Federal Trade Commission and Internet Privacy”, Marketing Research, 12 (3), 2000, pp.39-41. [34] G. Hulme, “Lack of trust hampering online direct market- ing”, B to B, 90 (12), 10/10/2005, pp.4. [35] The New York Times, To Fight Identity Theft, a Call for Banks to Disclose All Incidents, March 21, 2007, Busi- ness/Financial Desk; SECTC. [36] Financial Executive, “Computer Disposal Raises Legal Issues”, Financial Executive, 19 (7), 2003, pp.11-12. [37] G.R. Gordon and N.A. Willox Jr., “Using Identity Authen- tication and Eligibility Assessment to Mitigate the Risk of Improper Payments”, Journal of Economic Crime Man- agement, 3 (1), 2005, pp.1-24. [38] Federal Trade Commission (2006), “Consumer Fraud and Identity Theft Complaint Data, January – December 2005”, http://www.consumer.gov/sentinel/pubs/Top10Fraud2005. pdf. [39] London School of Economics and Political Science, “The Identity Project: An Assessment of the UK Identity Cards Bill and Its Implication”, June 2005, pp. 1 – 318, retrieved from http://is2.lse.ac.uk/idcard/identityreport.pdf. |