Natural Science

Vol.5 No.8(2013), Article ID:35591,6 pages DOI:10.4236/ns.2013.58114

Using the tight binding approximation in deriving the quantum critical temperature superconductivity equation

![]()

Department of Physics, Faculty of Science, Sudan University of Science and Technology, Khartoum, Sudan; *Corresponding Author: mhhlo@qu.edu.sa

Copyright © 2013 R. Abd Elhai et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Received 8 May 2013; revised 8 June 2013; accepted 15 June 2013

Keywords: Superconductivity; High Critical Temperature; Tight Binding Approximation

ABSTRACT

Superconductivity is one of the most important phenomena in solid state physics. Its theoretical framework at low critical temperature  is based on Bardeen, Cooper and Schrieffer theory (BCS). But at high

is based on Bardeen, Cooper and Schrieffer theory (BCS). But at high  above 135, this theory suf- fers from some setbacks. It cannot explain how the resistivity abruptly drops to zero below

above 135, this theory suf- fers from some setbacks. It cannot explain how the resistivity abruptly drops to zero below , besides the explanation of the so called pseudo gap, isotope and pressure effect, in addition to the phase transition from insulating to superconductivity state. The models proposed to cure this drawback are mainly based on Hubbard model which has a mathematical complex framework. In this work a model based on quantum mechanics besides generalized special relativity and plasma physics. It is utilized to get new modified Schrödinger equation sensitive to temperature. An expression for quantum resistance is also obtained which shows existence of critical temperature beyond which the resistance drops to zero. It gives an expression which shows the relation between the energy gap and

, besides the explanation of the so called pseudo gap, isotope and pressure effect, in addition to the phase transition from insulating to superconductivity state. The models proposed to cure this drawback are mainly based on Hubbard model which has a mathematical complex framework. In this work a model based on quantum mechanics besides generalized special relativity and plasma physics. It is utilized to get new modified Schrödinger equation sensitive to temperature. An expression for quantum resistance is also obtained which shows existence of critical temperature beyond which the resistance drops to zero. It gives an expression which shows the relation between the energy gap and . These expressions are mathematically simple and are in conformity with experimental results.

. These expressions are mathematically simple and are in conformity with experimental results.

1. INTRODUCTION

Superconductivity (SC) was discovered in 1911 in the Leiden laboratory of Kamerlingh Onnes when a so called “blue boy” (local high school student recruited for the tedious job of monitoring experiments) noticed that the resistivity of Hg metal vanished abruptly at about 4 K. Although phenomenological models with predictive power were developed in the 30’s and 40’s of the last century [1], F and H London developed the successful phenomenological approach in 1935 describing the behavior of superconductors in the external magnetic field. Ogg Jr. proposed a root to high-temperature superconductivity (HTSC) introducing electron pairs in 1946 and Ginzburg and Landau proposed the phenomenological theory of the superconducting phase transition in 1950 providing a comprehensive understanding of the electromagnetic properties below Tc [2]. The microscopic mechanism underlying superconductivity was not discovered until 1957 by Bardeen Cooper and Schrieffer (BCS) [1]. Superconductors have been studied intensively for their fundamental interest and for the promise of technological applications which would be possible if a material which superconducts at room temperature was discovered. Until 1986, critical temperatures (Tc’s) at which resistance disappears were always less than about 23 K.

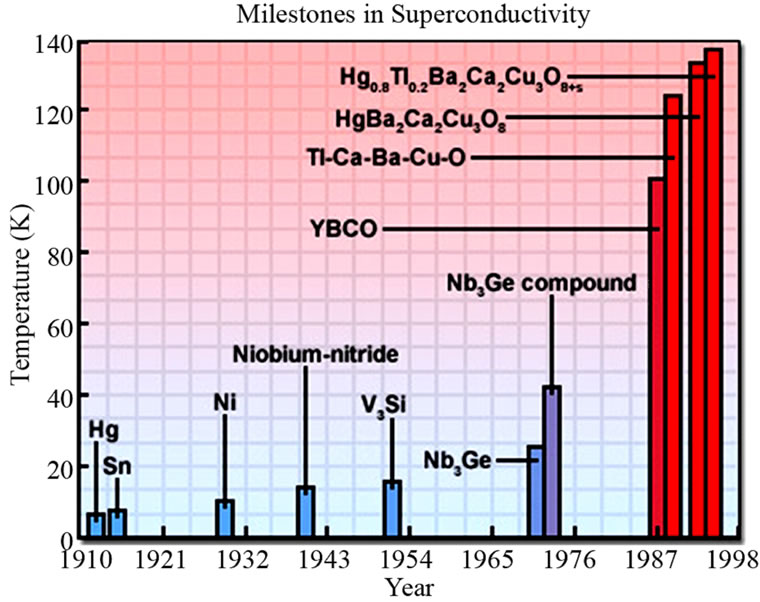

In 1986, Bednorz and Mueller published a paper, subsequently recognized with the 1987 Nobel Prize, for the discovery of a new class of materials called (HTSC) which currently include members with Tc’s of about 135 Kor more. Enormous numbers of studies have been carried out to clarify the mechanism of the high temperature superconductivity (HTSC) beyond the conventional BCS theory Figure 1.

One of the important HTSC is the cuprate compounds. The cuprate systems show not only high temperature superconductivity but also show various unusual behaviors when doped with holes where it is converted from an insulator to a superconductor [1]. The transition-metal oxides have been extensively investigated in recent years as materials that can be converted to superconductors. Understanding the nature of superconductors has been

Figure 1. History of superconductivity.

the most challenging issue in condensed matter physics due to the difficulties inherent in the many-body interactions.

Although BCS theory explains several superconductors phenomena specially at low critical temperature Tc, but there are many setbacks associated with Bardeen, Cooper and Schrieffer BCS theory for high critical temperature , which was observed in some compounds specially CuO and Fe compounds.

, which was observed in some compounds specially CuO and Fe compounds.

There are many problems need to be solved. First of all, one observes that, till now, there is no well established theoretical expression in most celebrated SC models which shows how the resistance drops abruptly to zero below the critical temperature. The existence of an energy gap well above Tc with pressure and the substitution of O16 by its isotope O18 affecting Tc also need to be explained by a simple model also.

The aim of this work is to construct quantum mechanical model based on plasma equation to construct a quantum model which explains why the resistance vanishes below critical temperature. It also aimed to find a useful expression for the energy gap. These contribution are exhibited in Sections (5) and (6). Section (2) is devoted for the theoretical plasma equation.

2. PLASMA EQUATION

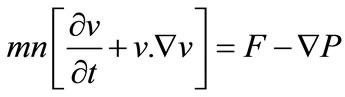

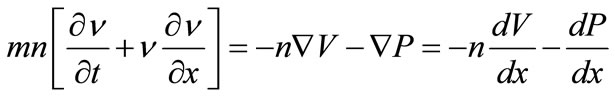

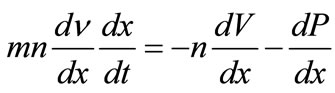

According to plasma equation, a fluid of particles of mass m, number density n, velocity , force F and pressure P is given by

, force F and pressure P is given by

(1)

(1)

If F is a field force then

Where V is the potential of one particle. In one dimension

(2)

(2)

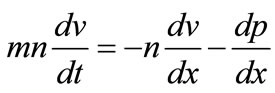

Thus according to Equation (1), in one dimension

(2’)

(2’)

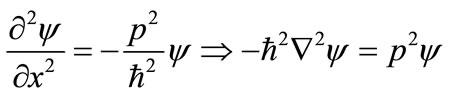

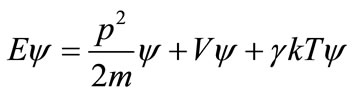

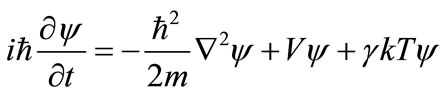

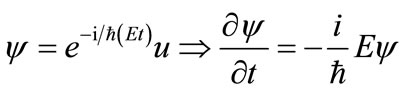

3. SCHRÖDINGER TEMPERATURE DEPENDENT EQUATION

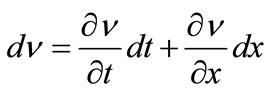

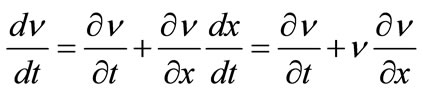

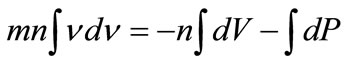

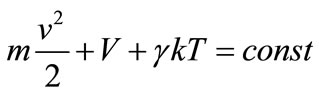

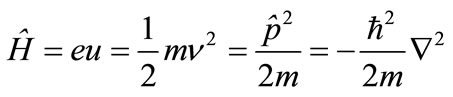

Schrodinger equation can be derived by using new expression of energy obtained from the plasma equation to do this one can use (2) to get

Multiplying both sides by dx and integrating yields

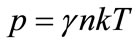

Considering the pressure to be  in general, thus

in general, thus

Hence

This constant conserved quantity looks like the ordinary energy beside the ordinary thermal energy term .

.

(3)

(3)

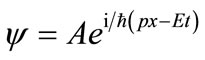

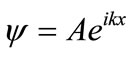

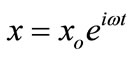

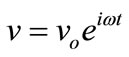

To find Schrödinger equation for it, consider the ordinary wave function

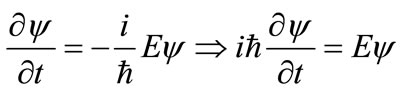

Differentiating both sides by t and x yields

(4)

(4)

Multiplying both sides of Equation (3) by  yields

yields

Substituting Equation (4), one gets

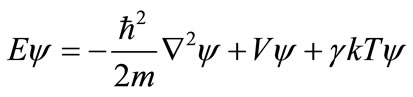

This equation represents Schrödinger equation when thermal motion is considered. The solution for time free potential can be

The time independent Schrödinger equation thus takes the form

(5)

(5)

For constant potential, the solution can be

,

,

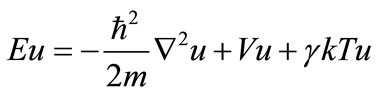

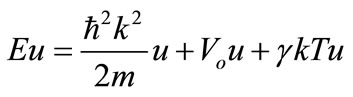

Inserting this solution in Equation (5) yields

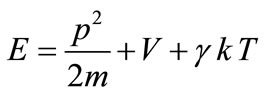

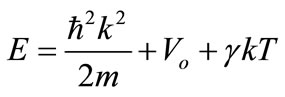

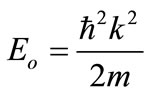

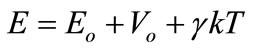

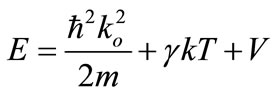

If one set the kinetic term to be , one can thus write the energy in the form

, one can thus write the energy in the form

(6)

(6)

This quantum energy expression involves a thermal term beside kinetic and potential term.

4. QUANTUM RESISTANCE

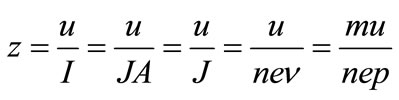

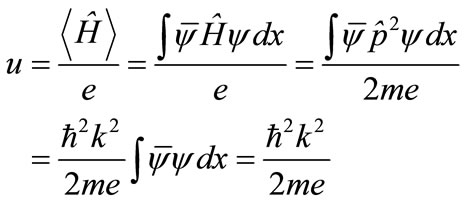

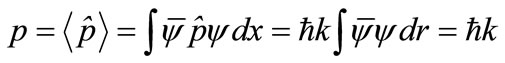

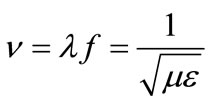

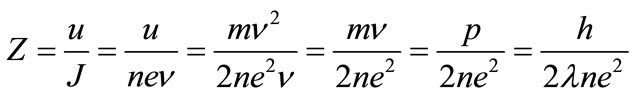

The resistance, z, per unit length (L = 1) per unit area (A = 1) can be found from the ordinary definition of, z. The resistance z is defined to be the ratio of the potential, u, to the current per unit area, J, i.e.

(7)

(7)

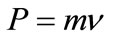

With n and e standing for the free hole or electron density and charge respectively, while p represents the momentum of electron of mass m, where .

.

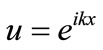

This resistance (it actually stands for resistivity) can be found by using the laws of quantum mechanics for a free charge which are responsible for generating the electric current, where the wave function takes the form

(8)

(8)

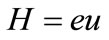

This selection of  comes from the fact that the resistance property comes from the motion of the free charges. The potential u is related to the Hamiltonian H through the relation

comes from the fact that the resistance property comes from the motion of the free charges. The potential u is related to the Hamiltonian H through the relation

Thus for freely moving charge one gets:

In view of Equation (8) and according to the correspondence principle V takes the form

(9)

(9)

While P becomes

(10)

(10)

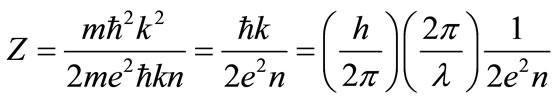

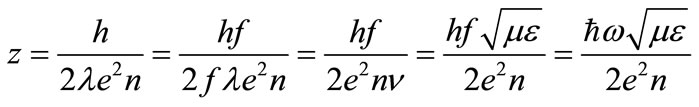

Thus inserting Equations (9), (10) in (7) one obtains

(11)

(11)

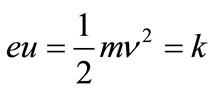

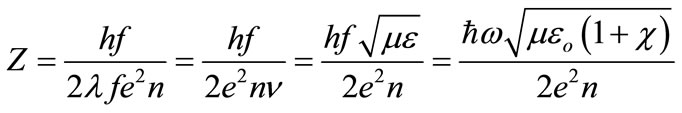

where the expression  for velocity is found by assuming charges to be waves, then following the electromagnetic theory (EMT), the speed of the waves is affected by electric permittivity

for velocity is found by assuming charges to be waves, then following the electromagnetic theory (EMT), the speed of the waves is affected by electric permittivity  and magnetic permeability through the relation

and magnetic permeability through the relation

(12)

(12)

where the effect of medium changes the wave length,  , while the frequency, f, is unchanged. Thus assuming the charge density, n, to be constant, the only change of, Z, can be caused by

, while the frequency, f, is unchanged. Thus assuming the charge density, n, to be constant, the only change of, Z, can be caused by  and

and .

.

It is also important to note that, in superconductors, the current can flow without the aid of deriving potential u. the role of u is confined only in enabling electrons to gain kinetic energy through the relations

(13)

(13)

where this potential can be applied between any two arbitrary points in the superconductors then remove it. The role of resistive force is neglected here as done in deriving London equations.

The expression for Z can also be found by inserting Equation (13) in to get

(14)

(14)

It is important to note that this quantum resistance expression resembles the ones found by Tsui [3] where one uses De Broglie hypothesis [4], i.e. .

.

5. CALCULATION HTSC BY ELECTRIC SUSCEPTIBILITY

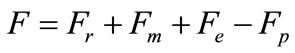

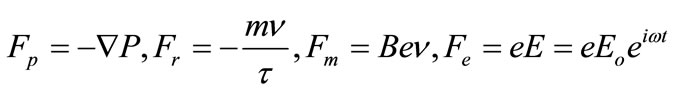

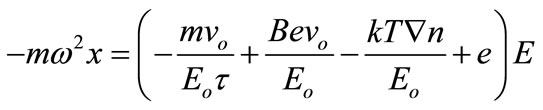

Consider holes in a conductor having resistive force Fr, magnetic force Fm and pressure force Fp, beside the electric force Fe, the equation motion then becomes [3]:

where

P, x, m,  ,

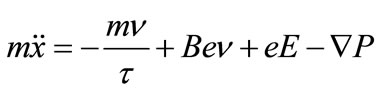

,  , B, e and E stands for the pressure, displacement, mass, velocity, relaxation time, magnetic flux density, electron charge and electric field intensity respectively. Thus the equation of motion takes the form

, B, e and E stands for the pressure, displacement, mass, velocity, relaxation time, magnetic flux density, electron charge and electric field intensity respectively. Thus the equation of motion takes the form

(15)

(15)

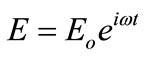

The solution of this equation can be suggested to be:

(16)

(16)

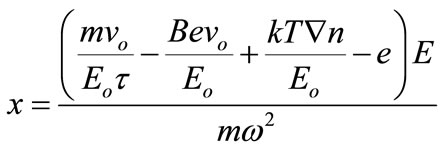

Inserting (16) in (15) yields

(17)

(17)

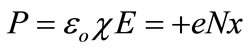

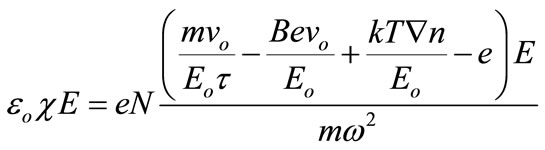

This expression of x can be utilized in the formula which relates the electric polarization vector P to the susceptibility  on one hand and to the number of atoms N via the following relation

on one hand and to the number of atoms N via the following relation

(18)

(18)

Motivated by the important role of holes in HTSC, displacement can be assumed to result from the motion of holes or positive nuclear charges, thus inserting Equation (17) in (18) yields

(19)

(19)

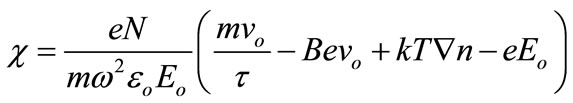

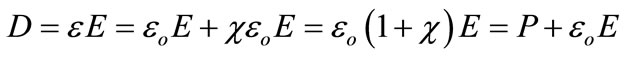

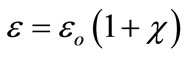

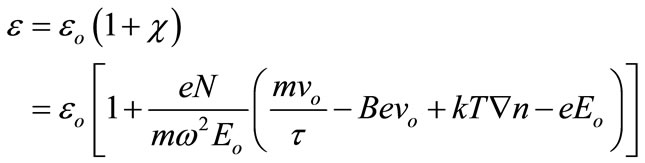

The electric flux density assumes the following relation

The electric permittivity is given by

(20)

(20)

The electric permittivity is thus given according to Equation (20) to be

(21)

(21)

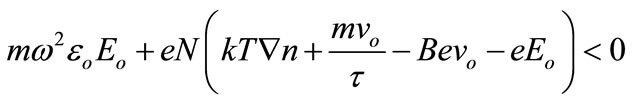

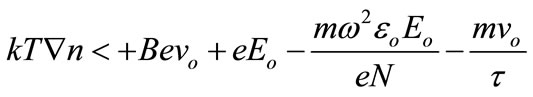

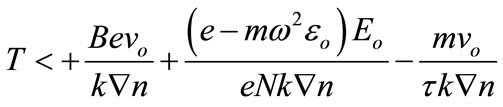

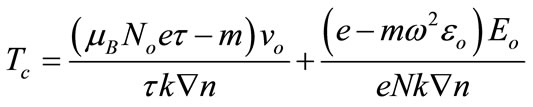

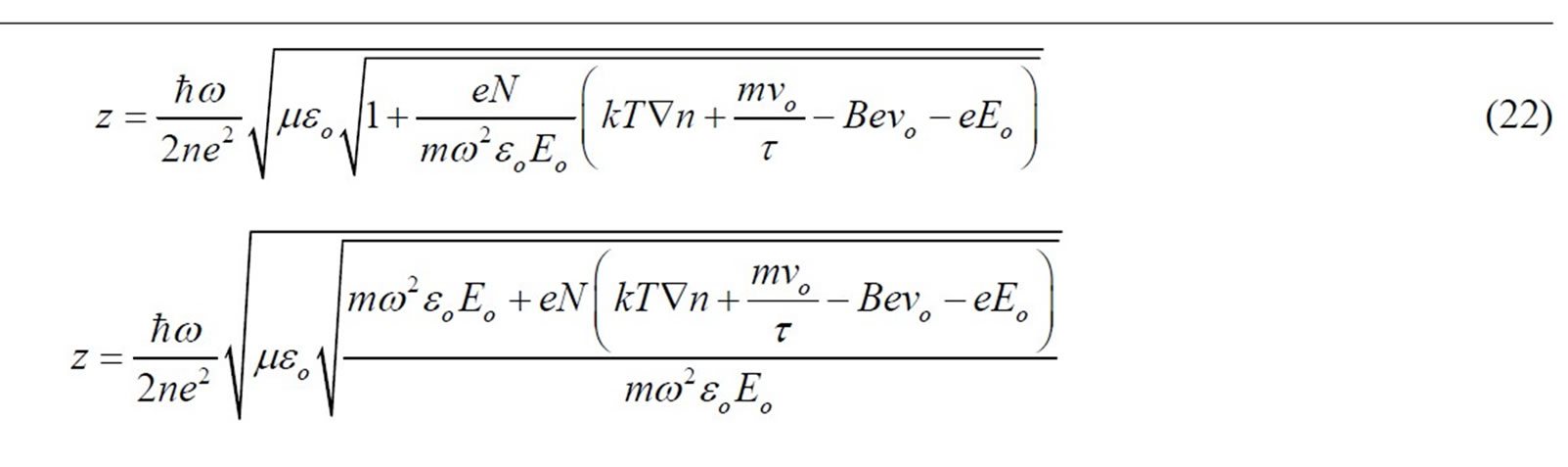

The resistance Z can be found by inserting (21) in (14) to get:

Thus the critical temperature is given by

(23)

(23)

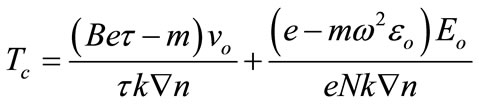

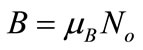

If the internal field B results from No atoms each having a verge flux density  then: [5].

then: [5].

(24)

(24)

Therefore Tc can take the form

(25)

(25)

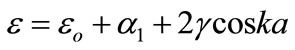

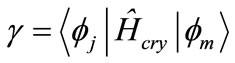

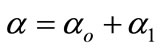

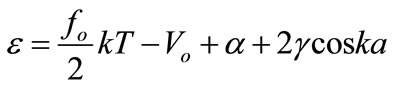

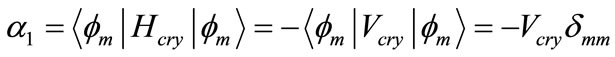

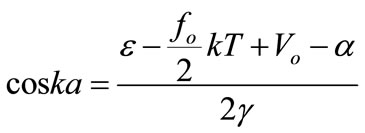

6. TIGHT BINDING CRITICAL TEMPERATURE AND ENERGY GAP

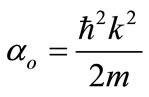

In tight binding model [5] the energy of electrons in

the crystal is given by

(26)

(26)

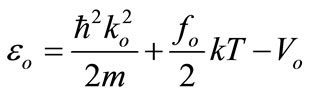

where  is the energy in the absence of crystal fieldwhile the other terms describe the effect of the crystal field. The energy

is the energy in the absence of crystal fieldwhile the other terms describe the effect of the crystal field. The energy  can split into two terms the kinetic part which can describe the thermal motion in the form

can split into two terms the kinetic part which can describe the thermal motion in the form

beside the potential term

beside the potential term  for attractive force or bounded particle.

for attractive force or bounded particle.

Thus one can write

(27)

(27)

represents the degrees of freedom.

represents the degrees of freedom.

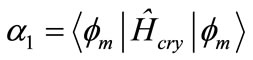

The terms describing the effect of the crystal force are

(28)

(28)

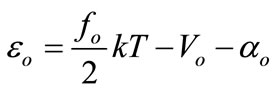

In view of Equations (26) and (27)

(29)

(29)

Here  stands for the crystal force Hamiltonian part, while

stands for the crystal force Hamiltonian part, while  and

and  are the states of particles located at the site m and j respectively.

are the states of particles located at the site m and j respectively.

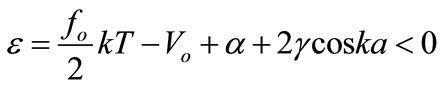

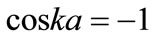

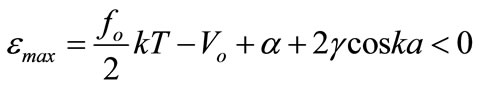

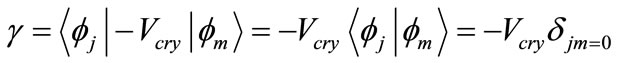

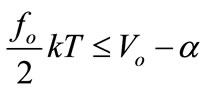

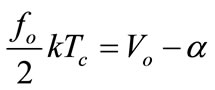

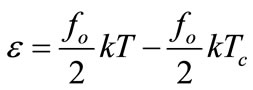

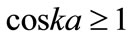

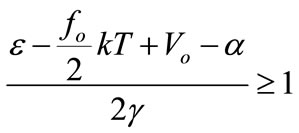

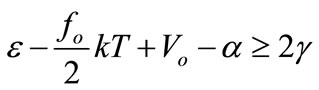

The superconductor is characterized by the existence of energy gap. This gap can be under stood here in two ways. If the electrons or holes are not free. This requires E to negative. Thus Equations (27) and (26) needs

(30)

(30)

Or the max value of  where

where  is less than zero, i.e.

is less than zero, i.e.

(31)

(31)

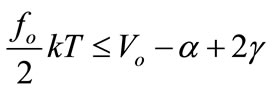

For constant attractive crystal force

(32)

(32)

Thus

Thus the critical temperature is given by

(33)

(33)

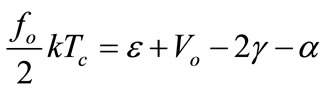

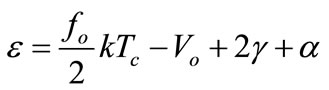

Substituted Equation (33) beside Equation (32) in Equation (30) one gets

(34)

(34)

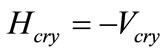

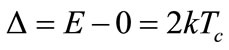

The energy gap  s equal to the difference between zero energy in conduction band and the negative energy in the valence band. Thus

s equal to the difference between zero energy in conduction band and the negative energy in the valence band. Thus

Since this relation holds for  one can neglect T since it is small to get

one can neglect T since it is small to get

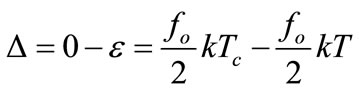

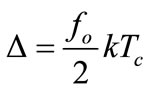

Equation (30) can also be utilized to get the forbidden energy states which characterizes superconductors, where

The energy is forbidden when

Thus the critical temperature

(35)

(35)

The forbidden energy is thus related to the critical temperature through the relation

(36)

(36)

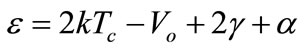

If the particle has a 4—degree of freedom, 3—translational and one vibration.

(37)

(37)

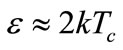

In view of Equations (32) and (28), since Plank constant is very small and for very small crystal field and for bound force , since the energy gap ∆ is the difference between bound valence energy E, and minimum free conduction electron energy zero. Thus

, since the energy gap ∆ is the difference between bound valence energy E, and minimum free conduction electron energy zero. Thus

(38)

(38)

Which shows linear relation between ∆ and Tc, thus it resembles the empirical relations. Where the energy gap is found to be  [6].

[6].

7. DISCUSSION

This model predicts that Schrödinger equation can be derived by using a new expression of energy obtained from the plasma equation. This expression includes thermal energy beside kinetic and potential energy according to Equation (6) It is very striking to note that this expression resembles the expression of the thermodynamic internal energy. A useful quantum expression for resistivity is also obtained in Equation (11) this expression resembles those obtained by Aharonove, Bohm and Berry as pointed out at the end of section 4. The model predicts that the resistivity of low and high Tc superconductors it drop abruptly when Z1 = real = zero according to Equation (8). It also finds the critical temperature Tc beyond which the resistivity vanish according to Equations (23) and (24). A useful expression for the energy gap which is dependent on Tc is also obtained. This expression is in agreement with the empirical relation.

8. CONCLUSIONS

The plasma equation is utilized to derive new energy expression in which thermal energy is added to the ordinary kinetic and potential energy. This quantum equation which is temperature dependent within the framework of this equation uses tight binding approximation besides the quantum impedance expression, and it is very easy to explain why resistance vanishes below a certain critical temperature and why the empirical relation between the energy gap and the critical temperature is linear.

This raises a hope that Schrodinger quantum temperature dependent model can be utilized, if a frictional effect can be incorporated in it, to construct a general theoretical frame work capable of describing Schrodinger phenomena. The result obtained indicates that the quantum plasma model can improve the theoretical model to explain some of the phenomena associated with the HTSC. Strictly speaking it can explain why the resistance drops abruptly below Tc, besides explaining some important effects like the relation between energy gap and critical temperature.

![]()

![]()

REFERENCES

- Kittle, C. (1976) Introduction to solid state physics. 5th Edition, John Wiley & Sons, New York.

- Alexandrov, A.S. (2003) Theory of superconductivity from weak to strong coupling, IoP Publishing, Norwich.

- Tsui, D.C, Stormer, H.L and Gossard, A.C (1982) Twodimensional magneto transport in the extreme quantum limit. Physical Review Letters, 48, 1559. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.48.1559

- Khwjali, A. (2009) Solid state physics. Azzaph press, Sudan.

- Halliday, D. and Resnick, R. (1974) Fundamentals of physics. John Wiley, Sons, Inc., New York.

- Burns, G. (1985) Solid state physics. Academic Press, Cambridge, 755 p.