Health

Vol.5 No.6A2(2013), Article ID:33710,8 pages DOI:10.4236/health.2013.56A2010

Professional identities of occupational therapy practitioners in Japan

![]()

1Department of Rehabilitation, Megumino Care Support-Elderly Care Nursing Facility, Eniwa, Japan; *Corresponding Author: risa.ot.taka@gmail.com

2Faculty of Health Sciences, Hokkaido University, Sapporo, Japan

Copyright © 2013 Risa Takashima, Kazuko Saeki. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Received 16 April 2013; revised 16 May 2013; accepted 1 June 2013

Keywords: Occupational Therapist; Professional Identity; Grounded Theory Approach

ABSTRACT

To aim to inductively clarify the professional identity of occupational therapists who work in a clinical setting, the researchers interviewed the 22 occupational therapists who had a minimum of 5 years or more of practice in the field. The professional identities of the practicing occupational therapists were constructed by the following two core categories: “harmonizing with a client’s life and the characteristic of a client’s disability”, and “giving clients sovereignties as a mission of the occupational therapists”. The occupational therapist can carry the role of coordinator in an interdisciplinary team for the clients with disability by understanding them. This is achieved based on the core category called “giving clients sovereignties as a mission of the occupational therapists”. Furthermore, in order to achieve the clients’ sovereignties, the occupational therapist can be an operational unit by planning practical strategies and practicing them based on the core category called “harmonizing with a client’s life and the characteristic of a client’s disability”. The fact is often difficult for these clients that they are concerned with how he/she lived actively. It is through unique ways of contributing for the clients in a team of professionals that the occupational therapists try to understand the clients not as “patients” but as “human beings”, and try to harmonize with their life and the characteristics of their disability, then try to support and empower them to reach a stage in which they have the sovereignties of their lives.

1. INTRODUCTION

In the medical and welfare fields, because the individuality of a client is emphasized more and more, and the clients’ needs are becoming various, the cooperation in an interdisciplinary team is becoming essential. In order to promote the smooth cooperation in an interdisciplinary team, it is important that each professional has a clear professional identity, and he/she advances the collaboration and differentiation in the interdisciplinary team. This way could clarify who the professional is, and how he/she can contribute to the client and the interdisciplinary team.

An occupational therapist is a rehabilitation specialist who performs occupational therapy. Occupational therapy is a client-centred health profession concerned with promoting health and well being through “occupation” [1]. Occupational therapists work for clients who need the rehabilitation in interdisciplinary teams. For example, they work with the following professionals in a physical disability domain: a doctor, a nurse, a physical therapist, a speech therapist. They work with the following professionals in a mental disability domain: a doctor, a nurse, a licensed psychiatric social worker, a certified clinical psychologist. They work with the following professionals in a developmental disability domain: a nurse, a physical therapist, a speech therapist, a childcare worker, a teacher. They work with the following professionals in an elderly disability domain: a nurse, a physical therapist, a speech therapist, a licensed nursing care worker, a social worker, a care manager. In interdisciplinary teams for clients who need rehabilitation, occupational therapists have the role of the coordinator crossing the plural professional fields and occupational therapists are expected that they can uniquely contribute to the clients.

According to Human Resource Project 2012 by World Federation of Occupational Therapists (WFOT), Japanese occupational therapists accounted for 15%, about 5700 professionals, among occupational therapists of 73 countries who took part in WFOT in 2011 [2]. This is the second biggest number after the United States in the world. Moreover, in Japan, about 6000 new occupational therapists graduate every year, due to the increase in the number of training schools. In Japan, occupational therapies for people who had mental or physical disabilities were mainstream, but, because the need for occupational therapists by the society is expanding, the professional fields of occupational therapy are magnifying to developmental and elderly disabilities domains; moreover, community domain in which occupational therapists perform the visiting rehabilitations for the clients who live in community is also expanding.

The occupational therapy field is developing due to the increasing numbers of occupational therapists and expanding professional domains; however, this expansion has made it unclear, for occupational therapists themselves and those around them, who occupational therapists are, and how they can contribute to the clients. Because occupational therapists are one of the main tools when they perform the services for the clients, it is important that occupational therapists have a strong awareness of their professional identity due to its connection with the quality of the therapy.

In the United States, Kielhofner [3] edited the historic transition of the occupational therapy using a concept of a paradigm. In Japan, it is the present conditions that actual investigating researches are almost inexistent though there are a great many opinions offered and comments about professional identities and specializations of occupational therapists.

Therefore, the purpose of this study is to clarify the professional identities of the occupational therapists who work in the fields.

The significance of this study is to support practitioners to have clear professional identities by inductively clarifying the professional identities of the occupational therapists who work in the fields. Clear professional identities could enable occupational therapists to declare their viewpoints, values, problems and the methods to solve them as an occupational therapist; moreover, clear professional identities could give one’s job significance [4]. In addition, clarifying the professional identities might promote differentiations [5] between the other professionals. By promoting collaborations in interdisciplenary teams, the professionals could offer an optimal service.

2. METHODS

This study employs a qualitative study method because of the following three reasons: the professional identity of occupational therapists is a domain which isn’t fully understood, this research needed to deal with a complicated context of the phenomenon, and this study aimed to build a theory reflected on the reality.

This study aimed to inductively clarify a professional identity of occupational therapists who works in a clinical setting. This study used Grounded Theory Approach (GTA) in qualitative study methods because it is suitable to provide an answer to what happens in the actual scene, and it is good at inductive theorization [6].

2.1. Participants

The participants of this study were practicing occupational therapists. The first criterion for selecting participants is that they must have a minimum of 5 years or more of practice in the field because they were expected their professional identities were stable in some degree. The second is that participants worked at the actual scene such as a hospital, a facility and so on at the time of the interview. Occupational therapists who worked as researchers and/or teachers of a training school for occupational therapy students were not considered in this research.

First, the researchers elected some occupational therapists who were interested in themselves as an occupational therapist and would be willing to reflect on and discuss it at the interview. Thereafter, the researchers used snowball sampling in which a participant introduces the next participant.

In addition, a theoretical sampling was taken about a domain according to gender, professional education history, years of experience, and working setting based on the following client’s disability domains: physical, mental, developmental, and elderly disability domains.

A theoretical sampling is a purposive sampling; in order to maintain a homogenous pool of participants, deliberate selection of participants according to their traits/ characteristics was made.

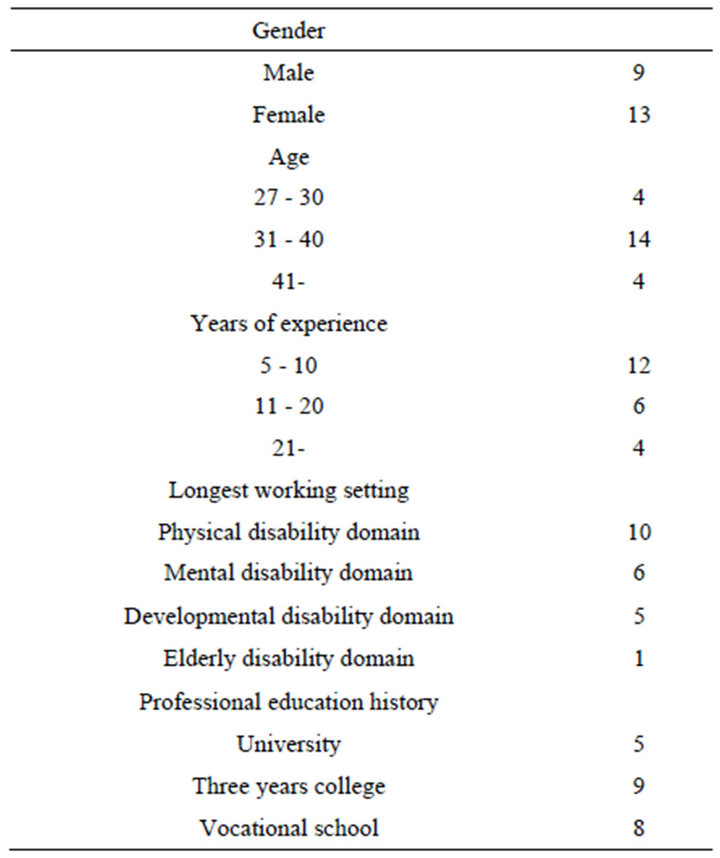

The participants of this study were finally 22 practicing occupational therapists who were 28 - 49 years old, 9 men and 13 women, and had 6 - 26 years of practice in the field. Table 1 shows a summary of the basic information of the participants.

2.2. Data Collection

First, all participants filled out face sheets about their basic context. The items of the face sheets were a name, age, sex, present and past workplaces, experience years as an occupational therapist, and experience in the following domains: physical, mental, developmental, and elderly disability domains.

Next, semi-structured interviews were conducted individually. Interview took 40 - 85 minutes. The location of each interview was chosen according to their general atmosphere and convenience for the participants e.g. a

Table 1. Characteristics of the participants (n = 22).

private room at a participant’s workplace or the researchers’ university, or a participant’s house.

The interviews items were real feelings of their identities as occupational therapists; a sense of values as an occupational therapist; originalities of an occupational therapist; cognitions by clients and other professionals; and the ideal image of an occupational therapist. Participants received an interview guide before the interview. Though the interview guide was considered, spontaneous and genuine contributions from participants were prioritized. As conversations developed, participants were allowed to talk freely. All interviews were recorded in an IC coda with the permission of the participant. All interviews were written down word for word. The interviewer made a note of a participant’s facial expressions, body language and other behaviors noticed during an interview, and the note was referred to on the data analysis.

2.3. Data Analysis

At the first stage of the data analysis, the researchers repeatedly read the transcripts to soak the data. Next, the transcripts were punctuated by every one meaning contents or episodes in interviewees’ stories, and each part was conceptualized, and one or more codes were created from a part of a transcript. In other words, the meaning contents that divided the data were rearranged in more abstract expressions, and were named according to each content.

Next, the researchers compared codes, and put similar codes in a new category, which was then given a name. In the present study, data were categorized through 4 phases. Cording and categorizing were performed concurrently. The case analysis about the data of the each participant and the comparative analysis between cases were repeatedly conducted. Then, the researchers pursued the core category. It is the central category of the study, and all other concepts are connected below it.

2.4. Ensuring Trustworthiness and Authenticity

Glaser and Strauss [7] indicated it is doubtful whether the standard of quantitative research can apply as the standard of a qualitative research, and the other standard based on the features of a qualitative research is more desirable. Therefore, this study employed the valuation standard of the trustworthiness [8] and the authenticity [9] which were developed for a qualitative research. The trustworthiness of a qualitative research means the soundness and the adequacy of the methodology. The authenticity of a qualitative research means the justice of a study and the usefulness for the participants.

The present study performed the following to ensure the trustworthiness and authenticity: critical examination for clarifying a premise of the research and a prejudice of the researchers; search of an opposite case or an alternative interpretation; detailed and thick description about a participant; member check by participants; professional check by the teacher of occupational therapist; supervision by the researcher who is well versed in a qualitative research; and detailed description of the analyzing process.

2.5. Ethical Considerations

Objectives, methodology, risks and benefits of this research were explained to all participants. Verbal and written consent was obtained from all participants.

The study was approved by the ethics committee of the Faculty of Health Sciences, Hokkaido University (approved number 11-10).

3. RESULTS

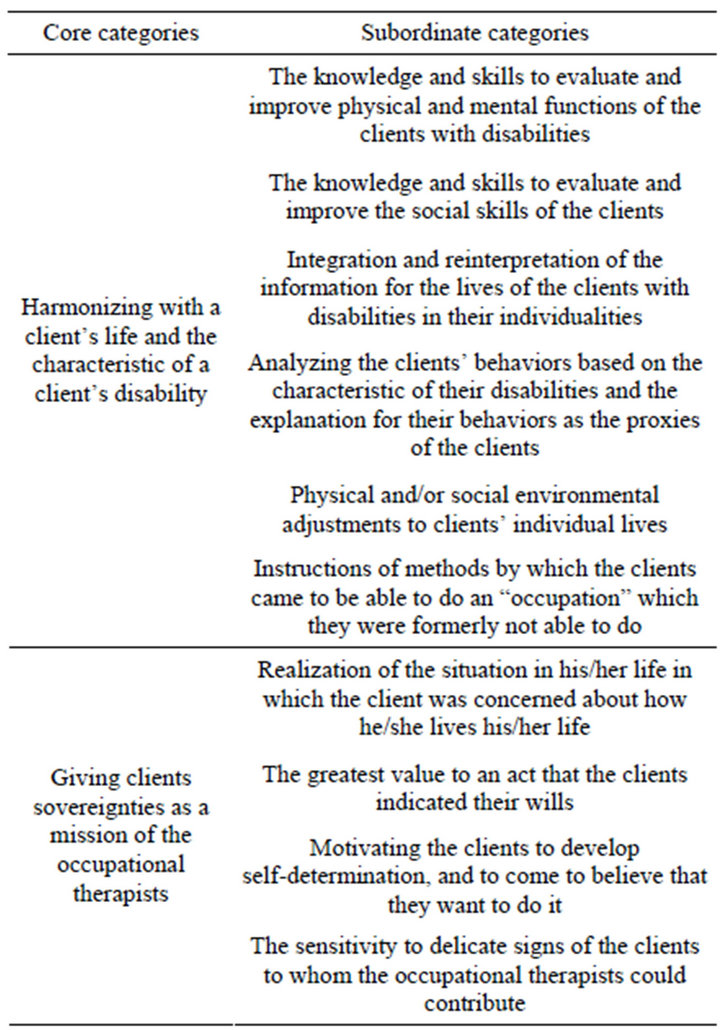

The professional identities of the practicing occupational therapists were constructed by the following two core categories: “harmonizing with a client’s life and the characteristic of a client’s disability”, and “giving clients sovereignties as a mission of the occupational therapists”. These two core categories were the main themes through this research. Table 2 shows the categories which constructed the two core categories.

The participants referred to their clients using a range of names e.g. a patient, a subject, a member, a child, and a person. However, because the participants usually rec-

Table 2. The two core categories and the subordinate categories of the professional identities.

ognize that clients were people who had disabilities instead of diseases, this study transcribed any of said references as simply “clients”.

3.1. The First Core Category; “Harmonizing with a Client’s Life and the Characteristic of a Client’s Disability”

This core category was generated by the undermentioned six categories.

The first category is “the knowledge and skills to evaluate and improve physical and mental functions of the clients with disabilities”. The participants recognized that their clients congenitally or posteriori had certain physical and/or mental disabilities, for example autism and schizophrenia, stroke, and they had some kind of difficulties in living. Therefore, it was essential for the practicing occupational therapists that they had the knowledge and skills to evaluate and improve physical and mental functions of the clients with disabilities.

The second category is “the knowledge and skills to evaluate and improve the social skills of the clients”. The occupational therapists especially focused on the clients’ social skills among the clients who had mental or developed disabilities. The social skills were used from the viewpoints of not only the evaluations but also the effect measurements.

The third category is “integration and reinterpretation of the information for the lives of the clients with disabilities in their individualities”. The participants thought how information was needed to support the clients in living individual and unique lives in spite of their disabilities. The participants collected information about the clients by using the professional knowledge and skills which were described in the two categories above, by talking with the clients, and by asking their families and the other professionals. Then, the participants reinterpreted that information based on the viewpoint of what significance did the information have for the one and only lives of the clients.

The fourth category is “analyzing the clients’ behaviors based on the characteristic of their disabilities and the explanation for their behaviors as the proxies of the clients”. For instance, when the client with autism or dementia behaved in a way that was a “mysterious” for the neighboring people, the participant analyzed and reinterpreted the reason of it based on the characteristic of the client’s disability. Moreover, the participants explained the clients’ “mystery” behaviors to the neighboring people and conveyed the concrete countermeasure for the behaviors. The participants thereby tried to create a comfortable envelopment for the clients and the neighboring people.

The fifth category is “physical and/or social environmental adjustments to clients’ individual lives”. The participants adjusted the physical environments of the clients such as their houses or welfare equipments. In addition, the participants also adjusted the social environments that focused on the relationships between the client and the other people e.g. the clients’ families, the neighborhoods, the clients’ colleagues, and the other professionals.

The sixth category is “instructions of methods by which the clients came to be able to do an ‘occupation’ which they were formerly not able to do”. Collected and integrated information about the clients were used to identify what “occupation” was needed and/or deemed important. Moreover, if the client was not able to perform it, the participants analyzed why he/she could not perform it, proceeded to develop a strategy for the client to come to be able to do it, and then instructed the clients based on the strategy. The fourth and fifth categories described above were some of the strategies.

3.2. The Second Core Category; “Giving Clients Sovereignties as a Mission of the Occupational Therapists”

This core category was generated by the undermentioned four categories.

The first category is “realization of the situation in his/ her life in which the client was concerned about how he/ she lives his/her life”. This category expressed a condition of human life which the participants considered as a desirable life. The participants recognized that it was an ideal condition in which the client had sovereignty of his/ her life, and the client was concerned by he/herself with how he/she lived, even when the clients needed a great deal of help in their life (e.g. because of stroke), or the clients were not fully capable of verbal communication (e.g. because of autism). The participants supported the clients to be able to get closer to the condition.

The second category is “the greatest value to an act that the clients indicated their wills”. The participants put great value on the clients’ declarations of wills that they want or do not want to do something e.g. whether they wanted to change clothes. In other words, the participants considered that this was the basics of occupational therapy practices, and the supporting actions to the client which the occupational therapists should perform.

The third category is “motivating the clients to develop self-determination, and to come to believe that they want to do it”. The participants thought that it was not desirable that the clients felt that they were made to do something they did not want to do, for example, a client being asked to do muscle training when he/she did not want to do it, and that the clients had the feeling of having their rehabilitation given by the occupational therapists instead of the feeling that the clients did rehabilitation by themselves. Therefore, it was in a desirable condition which the participants should aim at that the clients actively or positively or subjectively participated in their rehabilitations and activities. The participants tried to motivate the clients to realize it by various schemes.

The fourth category is “the sensitivity to delicate signs of the clients to whom the occupational therapists could contribute”. The participants decided the timing when they should be concerned with the clients, and the contents of service which the clients needed, according to the three viewpoints which were explained in the first, second, and third categories above. This category described the important readiness for the occupational therapy practices in order not to overlook the clients’ conditions which the occupational therapists could contribute to.

3.3. The Relationship between the Two Core Categories

The professional identities of the practicing occupational therapists were expressed by the following two core categories: “harmonizing with a client’s life and the characteristic of a client’s disability”, and “giving clients sovereignties as a mission of the occupational therapists”. The former category was a component of the identity closely connected with practices, and the latter one was a component which attached philosophical sigificance to the occupational therapy practices.

These two core categories sometimes supported by each other, but sometimes conflicted with each other. For example, the latter category gave the former one a philosophical meaning and significance for some participants. However, when one category was strongly emphasized in some participants, the other one was relatively neglected. Moreover, because of this reason, some participants had negative feelings against themselves as an occupational therapist, for instance “I don’t seem to be an occupational therapist”, when they practiced based on the other category which they were not devoted to.

4. DISCUSSION

4.1. The Significance of the Two Core Categories for Practicing Occupational Therapists

The instability of the professional identity of the occupational therapist has always been regarded as a problem [10-13]. It is the present condition that actual investigative researches are very few [14-16] though there are a great many opinions offered and comments made about professional identities and specializations of occupational therapists. In addition, many of those studies researched specific domains e.g. an acute setting or developmental disability domains. On the other hand, this study differs from these previous works, as it investigated the professional identity of occupational therapists who work in a clinical setting. Then, it inductively clarified the following two core categories: “harmonizing with a client’s life and the characteristic of a client’s disability”, and “giving clients sovereignties as a mission of the occupational therapists”.

When the occupational therapists serve their clients and achieve their aims, the core category named “harmonizing with a client’s life and the characteristic of a client’s disability” is exceedingly important. If an occupational therapist cannot perform “harmonizing with a client’s life and the characteristic of a client’s disability”, it might be difficult for him/her to fulfill the demands of his/her job as a practicing therapist.

As for the category named “giving clients sovereignties as a mission of the occupational therapists”, it states clearly the following missions and meaning of their existence: what situations of people the occupational therapists can or should contribute to, and which of these situations are desirable for the occupational therapists.

4.2. The Visible and Invisible Professional Identity of Occupational Therapists

Because occupational therapists have access to various knowledge and skills to deal with the high individuality and diversity of their clients, a wide area of support to the clients are included in the occupational therapists’ special fields. Historically, due to these wide special fields, it became difficult to distinguish occupational therapy from physical therapy, clinical psychology, and psychiatry, which are the proximity domains of occupational therapy, and eventually, occupational therapists lost their professional identities [17]. Another reason why the professional identities of occupational therapists may be weak is that the services in an occupational therapy are sometimes invisible, i.e. not perceptible.

Wit et al. [18] tried to clarify the differences between occupational therapy and physical therapy. The researchers recorded each one of the fifteen scenes of the occupational therapy and the physical therapy with a video camera to analyze the differences among them. Eventually, they clarified that the following scenes often appeared in the physical therapy: walking training, transferring, and balance training of a standing position and a reclining position. On the other hand, they clarified that the following scenes often appeared in the occupational therapy: training of an activities of daily life (ADL), housework, sensory, perception, and cognition.

In the present study, the core category named “harmonizing with a client’s life and the characteristic of a client’s disability” principally expresses the visible characteristics of the professional identity, and this category contains the factors which Wit et al. identified as the characteristics of the occupational therapy above. The visible characteristics can make it easy that occupational therapists and the other professionals understand who occupational therapists are.

However, this study found that the other core category named “giving clients sovereignties as a mission of the occupational therapists” is also an important professional identity of participants. This category expresses the invisible characteristics. Because it is difficult for the other professionals to recognize the invisible characteristics, the participants often feel that the other professionals do not understand or misunderstand them. In addition, because even the participants themselves were also confused about who they are, the invisible characteristics might become a cause of an identity crisis. Therefore, when occupational therapists and other people consider the professional identity of occupational therapists, they should pay attention to not only the visible but also the invisible characteristics.

According to the core category, occupational therapist can assume the role of coordinator in an interdisciplinary team because they can assess their clients and correct the information about them based on the concept of the clients’ sovereignties, which it is rather easy for the various professionals to share. Moreover, because the occupational therapists have concrete means of “harmonizing with a client’s life and the characteristic of a client’s disability” to achieve the clients’ sovereignties, they can uniquely contribute to the client in the team. Occupational therapists who work in a hospital, a facility, or a community often try to understand their clients not as “patients” but as “human beings”. While the clients live from the present time to the future with their disabilities, occupational therapists can assess the difficulties which are arising or will arise in the clients’ lives, and they can plan a concrete strategy to deal with it, and apply this strategy to solve it. This process is “harmonizing with a client’s life and the characteristic of a client’s disability”.

In comparing occupational therapists and the other professionals, assessing and coordinating the individual and unique life of a client with a disability as a human being might be common with nurses, social workers, and care managers. The part of strategies and practices to achieve the client’s life might be common with physical therapists, speech therapists, and clinical psychologists. However, the only professional whose special field includes all of these processes is the occupational therapist. Therefore, occupational therapists are highly versatile professionals who can assess which sides and processes are not enough in an interdisciplinary team according to the member, and can display the special knowledge about and skills in said sides and processes. Although the high versatility might be a cause of the identity crisis for occupational therapists, it can be a way to uniquely contribute to the clients, and it can be an advantage of occupational therapists.

4.3. The Suggestions as to Practices

The results of this study could be useful to enable practicing occupational therapists who are concerned about the development of their careers to construct their clear and stable professional identities.

In addition, because the results of this study show strong evidence with regards to clarifying the professional identities of the occupational therapists, the results might useful in educating practicing occupational therapists and occupational therapy students. In professional education, improving the development of the professional identity could lead to training the occupational therapists who are aware of what kind of contribution they can make, who can explain these contributions, and who have flexibility to manage various changes.

Moreover, the clarified professional identities of the occupational therapists might improve the differentiation between occupational therapists and the other professionals. This differentiation means the following conditions: when occupational therapists work with the other professionals e.g. physical therapists and nurses, they recognize the common and different points from each other, but, occupational therapists can draw a boundary line between them and the other professionals because they have the actual feeling that these are the professional fields of occupational therapists. An occupational therapist who understands who he/she is as a professional, and who has the clear sense of the professional identity might not need to be afraid that he/she overlaps the specialization with other professionals. Therefore, with the self-confidence that he/she is an occupational therapist, he/she can make good partnerships with the other professionals.

If occupational therapists can recognize the common and different points among various professionals, they could consider that they should collaborate with other professionals according to their clients’ needs. If occupational therapists can make the other professionals understand who an occupational therapist is by using the results of this study, the other professionals might understand how they can employ occupational therapists in the interdisciplinary team. Consequently, the results of this study could improve an advanced team approach.

4.4. The Significance of the Present Study and the Issues Which Are Needed to Be Worked on

The participants included the occupational therapists who worked in the following wide domains: physical, mental, developmental, elderly disability, and community domains. Although the number of the participants, 22 therapists, is limited, this study constructed the basic theory about the professional identity of these occupational therapists who were working in the wide domain.

Both the core categories and the subordinate categories which composed the core categories are related to the client because of the participants’ backgrounds, since they all are practicing therapists, and they did not include teachers and/or researches. Therefore, the result should be understood as the professional identities which are characteristic of the practicing therapists.

The participants were therapists who had 6 - 26 years of practice in the field. The result should be interpreted as the professional identities of the occupational therapists who continued to work as occupational therapists, and whose experience ranged from mid-career practitioners to veteran professionals in senior positions.

Regarding aspects relating this study to an occupational therapist’s competence, satisfaction, and the feeling of being useful, further investigations might be necessary. Furthermore, this study did not consider the identity status [19] that expresses an identity condition e.g. achievement state and diffusion state. The following are also the issues which are needed to be worked on: influence factors of identity statuses and strategies to overcome diffusion state of professional identities.

5. CONCLUSIONS

This study investigated the professional identity of occupational therapists who work in a clinical setting, and inductively clarified the following two core categories: “harmonizing with a client’s life and the characteristic of a client’s disability”, and “giving clients sovereignties as a mission of the occupational therapists”.

The occupational therapist can carry the role of coordinator in an interdisciplinary team for the clients with disability by understanding them. This is achieved based on the core category called “giving clients sovereignties as a mission of the occupational therapists”. Furthermore, in order to achieve the clients’ sovereignties, the occupational therapist can be an operational unit by planning practical strategies and practicing them based on the core category called “harmonizing with a client’s life and the characteristic of a client’s disability”.

The fact is often difficult for these clients that they are concerned with how he/she lived actively. It is through unique ways of contributing for the clients in a team of professionals that the occupational therapists try to understand the clients not as “patients” but as “human beings”, and try to harmonize with their life and the characteristics of their disability, then try to support and empower them to reach a stage in which they have the sovereignties of their lives.

REFERENCES

- World Federation of Occupational Therapists (2012) Definition of occupational therapy. http://www.wfot.org/AboutUs/AboutOccupationalTherapy/DefinitionofOccupationalTherapy.aspx

- World Federation of Occupational Therapists (2012) Occupational Therapy Human Resources Project 2012. http://www.wfot.org/ResourceCentre.aspx

- Kielhofner, G. (2004) Conceptual foundations of occupational therapy. 3rd Edition, F. A. Davis Company, Philadelphia, 27-71.

- Kielhofner, G. (2004) Conceptual foundations of occupational therapy. 3rd Edition, F. A. Davis Company, Philadelphia, 2-10.

- Baumeister, R.F. (1986) Identity: Cultural change and the struggle for self. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

- Corbin, J. and Strauss, A. (2007) Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. Sage Publications, Inc., Thousand Oaks.

- Glaser, B. and Strauss, A.L. (1965) Discovery of substantive theory, a basic strategy underlying qualitative research. The American Behavioral Scientist, 8, 5-12. doi:10.1177/000276426500800602

- Lincoln, Y.S. and Guba, E.G. (1985) Naturalistic inquiry. Sage Publications, Inc., Thousand Oaks.

- Guba, E.G. and Lincoln, Y.S. (1989) Fourth generation evaluation. Sage Publications, Inc., Thousand Oaks.

- Dige, M. (2009) Occupational therapy, professional development, and ethics. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 16, 88-98.

- Kelly, G. and McFarlane, H. (2007) Culture or cult? The mythological nature of occupational therapy. Occupational Therapy International, 14, 188-202. doi:10.1002/oti.237

- Abreu, B.C. (2006) Professional identity and workplace integration. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 60, 596-599. doi:10.5014/ajot.60.5.596

- Ikiugu, M.N. and Schultz, S. (2006) An argument for pragmatism as a foundational philosophy of occupational therapy. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 73, 86-97.

- Wilding, C. and Whiteford, G. (2007) Occupation and occupational therapy: Knowledge paradaims and everyday practice. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 54, 185-193. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1630.2006.00621.x

- Whiteford, G., Townsend, E. and Hocking, C. (2000) Reflections on a renaissance of occupation. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 67, 61-69. doi:10.1177/000841740006700109

- Seruya, F.M. and Hinojosa, J. (2010) Professional and organizational commitment in paediatric occupational therapists: The influence of practice setting. Occupational Therapy International, 17, 125-134. doi:10.1002/oti.293

- Kielhofner, G. and Burke, J.P. (1977) Occupational therapy after 60 years: An account of changing identity and knowledge. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 31, 675-689.

- De Wit, L., Putman, K., Lincoln, N., Baert, I., Berman, P., Beyens, H., Bogaerts, K., Brinkmann, N., Connell, L., Dejaeger, E., De Weerdt, W., Jenni, W., Lesaffre, E., Leys, M., Louckx, F., Schuback, B., Schupp, W., Smith, B. and Feys, H. (2006) Stroke rehabilitation in Europe: what do physiotherapists and occupational therapists actually do? Stroke, 37, 1483-1489. doi:10.1161/01.STR.0000221709.23293.c2

- Marcia, J.E. (1966) Development and validation of ego identity status. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 3, 551-558. doi:10.1037/h0023281