Engineering

Vol.08 No.06(2016), Article ID:67825,17 pages

10.4236/eng.2016.86036

Smoothed Particle Hydrodynamic Modelling of Hydraulic Jumps: Bulk Parameters and Free Surface Fluctuations

Patrick Jonsson, Pär Jonsén, Patrik Andreasson, T. Staffan Lundström, J. Gunnar I. Hellström

Department of Engineering Sciences and Mathematics, Luleå University of Technology, Luleå, Sweden

Copyright © 2016 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received 19 May 2016; accepted 26 June 2016; published 29 June 2016

ABSTRACT

A hydraulic jump is a rapid transition from supercritical flow to subcritical flow characterized by the development of large scale turbulence, surface waves, spray, energy dissipation and considerable air entrainment. Hydraulic jumps can be found in waterways such as spillways connected to hydropower plants and are an effective way to eliminate problems caused by high velocity flow, e.g. erosion. Due to the importance of the hydropower sector as a major contributor to the Swedish electricity production, the present study focuses on Smoothed Particle Hydrodynamic (SPH) modelling of 2D hydraulic jumps in horizontal open channels. Four cases with different spatial resolution of the SPH particles were investigated by comparing the conjugate depth in the subcritical section with theoretical results. These showed generally good agreement with theory. The coarsest case was run for a longer time and a quasi-stationary state was achieved, which facilitated an extended study of additional variables. The mean vertical velocity distribution in the horizontal direction compared favorably with experiments and the maximum velocity for the SPH- simulations indicated a too rapid decrease in the horizontal direction and poor agreement to experiments was obtained. Furthermore, the mean and the standard deviation of the free surface fluctuation showed generally good agreement with experimental results even though some discrepancies were found regarding the peak in the maximum standard deviation. The free surface fluctuation frequencies were over predicted and the model could not capture the decay of the fluctuations in the horizontal direction.

Keywords:

SPH, Hydraulic Jump, Conjugate Depth, Free Surface Fluctuation, Vertical Velocity Distribution

1. Introduction

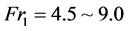

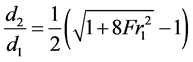

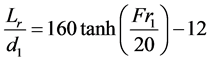

Fluid mechanics of large hydropower plants are characterized by very high flow rates and large physical dimensions both in production and spill waterways. The hydraulic head harvested in production needs to be handled when spillways are engaged. In open spillways, this is done by accelerating the flow and then using the dissipative features of a hydraulic jump. Hydraulic jumps are an effective way to eliminate problems caused by high velocity flow, e.g. erosion. The lower velocities past the jump may also create beneficial flow conditions for migrating species such as salmonoids [1] . A hydraulic jump is a rapid transition from high velocity supercritical flow to low velocity subcritical flow with rise of the free surface to keep continuity. The jump is characterized by the development of large scale turbulence, surface waves, spray, energy dissipation and considerable air entrainment. The highly turbulent transition zone is usually referred to as the roller and the start of the roller, the jump toe or the impingement point. A hydraulic jump is typically characterized by its inflow Froude number , where

, where  is the depth average upstream flow velocity;

is the depth average upstream flow velocity;  is the upstream depth and g is the acceleration of gravity, see Figure 1. Based on the

is the upstream depth and g is the acceleration of gravity, see Figure 1. Based on the , the jump may be classified into five types: undular

, the jump may be classified into five types: undular , weak

, weak , oscillating

, oscillating , steady

, steady  and strong

and strong  , each with its own distinct characteristics [2] . By applying the continuity and momentum equation in integral form, a dimensionless relationship of the upstream depth

, each with its own distinct characteristics [2] . By applying the continuity and momentum equation in integral form, a dimensionless relationship of the upstream depth  and downstream depth

and downstream depth  can be obtained. For a horizontal and rectangular channel this procedure yields the Bélanger equation [2] ,

can be obtained. For a horizontal and rectangular channel this procedure yields the Bélanger equation [2] ,

. (1)

. (1)

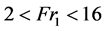

Hager, Bremen and Kawagoshi [3] reviewed a broad range of data and correlations and proposed a semi-em- pirical relationship for the length of the roller  as,

as,

, (2)

, (2)

in the range . The external geometry of hydraulic jumps has been studied for a long time and only recently, the internal flow structures have been considered. Depending on the type of jump, a number of regions in the roller can be identified [4] and [5] , see Figure 1. For steady jumps, a boundary layer is seen close to the bottom which transitions in the vertical direction are into a high velocity jet or core region. Continuing in the vertical direction from the bottom, a highly turbulent air-water shear layer is observed where bubble breakup and coalescences occur and momentum is transferred to the region above. The final region is a highly aerated recirculation region with significant free surface wave and splash production.

. The external geometry of hydraulic jumps has been studied for a long time and only recently, the internal flow structures have been considered. Depending on the type of jump, a number of regions in the roller can be identified [4] and [5] , see Figure 1. For steady jumps, a boundary layer is seen close to the bottom which transitions in the vertical direction are into a high velocity jet or core region. Continuing in the vertical direction from the bottom, a highly turbulent air-water shear layer is observed where bubble breakup and coalescences occur and momentum is transferred to the region above. The final region is a highly aerated recirculation region with significant free surface wave and splash production.

Several authors have investigated the velocity field in the abovementioned regions using different experimental techniques, e.g. [4] - [8] . Chanson [9] showed that the velocity profiles in the developing shear layer followed a wall jet pattern proposed earlier by [4] and [6] . The maximum velocity

Figure 1. Schematic figure of a hydraulic jump.

where x is the distance downstream of the inlet and

where

in the range

Modelling of highly disturbed aerated free surface flows such as hydraulic jumps, is complex when grid based method is used [21] . Severe problems with mesh entanglement and determination of the free surface have been encountered [22] . The meshfree, Lagrangian particle based method Smooth Particle Hydrodynamic (SPH) has shown to be a good alternative to grid based methods to overcome such problems [23] and [24] . The technique was first proposed independently by Lucy [25] and Gingold and Monaghan [26] in the late seventies to solve astrophysical problems in three-dimensional open spaces. Today, the SPH method has been applied to a number of fields and problems [24] and the maturity of the method has increased significantly. A major advantage of SPH is that the method is meshfree, thus considerable time is saved as compared to methods that need a predefined mesh. However, as the SPH is relatively unexplored as compared to traditional finite volume methods (FVM) or finite element method (FEM) methods there are some areas that still need considerable attention. For instance, wall boundary conditions are generally difficult to set in SPH as they do not appear in a natural way within the SPH formalism. Furthermore, the SPH method is typically slower computational wise since the time step depends on the speed of sound and the explicit integration techniques used.

A few papers have been devoted to SPH modelling of hydraulic jumps. López, Marivela and Garrote [27] investigated the capability of the SPH method to reproduce mobile hydraulic jumps with different inflow

Present study will focus on the general behavior of hydraulic jumps when using the meshless, Lagrangian particle method SPH. Special attention will be given on how the spatial resolution of the SPH particles impacts the overall behavior of the jump and the conjugate depth. Apart from the geometrical parameters such as depth, the internal velocity field and its impact on the free surface will be studied. Based on the averaged velocity field the jump length will be determined and compared to experiments. The instantaneous velocity field showed large coherent vortices which affected the free surface. The fluctuations of the free surface will be studied extensively and numerical results will be compared to experimental data, e.g. the standard deviation and fluctuations frequencies.

2. Method

2.1. Governing Equations

In the SPH-method, the fluid domain is represented by a set of non-connected particles which possess individual material properties, e.g. density, velocity and pressure [32] . Besides representing the problem domain and acting as information carriers the particles also act as the computational frame for the field function approximations. As the particles move with the fluid their material properties changes as a function of time and spatial co-ordinate due to interactions with neighboring particles. In the following text, the superscripts

where

where the kernel function is

In both Equation (8) and (9), h is the smoothing length;

where

The NULL material model implemented in software package LS-DYNA defines the deviatoric viscous stress as,

where

where

Polynomial EOS implemented in LS-DYNA [33] as,

where

where

A first order time integration scheme is used and the time step is determined according to,

where

2.2. Boundary Conditions

Wall boundaries were modelled as rigid shell finite elements and the coupling between the boundaries and the SPH-particles were governed by a penalty based “node-to-surface” contact-algorithm [33] [37] [38] . This is a so-called one-way contact where the SPH particles are defined as the slave side and the FEM elements as master side. In applying the penalty method, the slave nodes were checked for penetration through the master surface. If a slave node penetrated, an interface spring was placed between the master surface and the node. The spring stiffness was chosen approximately in the order of magnitude as the stiffness of the interface element normal to the interface. The resultant force applied to the SPH particle in the normal direction of the FEM element was proportional to the amount of penetration. As the normal component was considered only the wall boundaries are frictionless. This approach can be compared with the Lennard-Jones-type boundary condition where a central force is applied to fluid particles [36] .

2.3. Geometrical and Numerical Setup

A two dimensional horizontal spillway channel and hydraulic jump were investigated in present work with a single phase (water) model. The schematic geometrical setup is shown in Figure 2. Inside the computational box (dashed lines), SPH particles were activated meaning that the governing equations were solved. Outside the

Figure 2. Schematic geometrical setup. Dashed lines denotes the boundary of the computational box, thick black lines are the wall boundaries modelled as finite shell-elements and the thin black line is the initial free surface. The black box at the inlet section shows the location of the predefined particles entering the computational domain.

box, SPH particles maintained the state from previous active time step or an externally imposed state and hence no governing equations were solved. By placing a fixed number of SPH particles in an ordered configurationoutside the computational box an inlet was obtained, see the black box at the inlet section in Figure 2. The SPH particles entering the domain had a prescribed inlet velocity of

A perfect agreement of numerical and theoretical results implies that

3. Result and Discussion

In Figure 3 and Figure 4, the absolute velocity field for the coarsest

Table 1. Properties of the simulation cases.

Figure 3. Snapshots of the absolute velocity field [m/s] for the coarses case d1/4 between 0 s to 5 s. Color interpretation according to the colorbar, blue 0 [m/s] and red 1.6 [m/s].

Figure 4. Snapshots of the absolute velocity field [m/s] for the finest case d1/10 between 0 s to 5 s. Color interpretation according to the colorbar, blue 0 [m/s] and red 1.6 [m/s].

direction until it reached the weir, see Figure 3 & Figure 4 at 2 s. During this phase a minor difference the position of the jump toe was seen among the cases. At the weir, a bulking effect with linear increase of the free surface was observed and the jump toe shifted propagation direction, compare Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5. As the jump shifted to an upstream propagation direction the difference of the position of the jump toe increased. The more refined cases showed a lower upstream propagation rate compared to the less refined. It was assumed, however, that the propagation rate was not zero and thus the more refined cases would have reached the gate if the simulation time was increased. The coarsest case

Figure 5. Dimensionless conjugate depth d2,SPH/d2,THEORY as function of time. Above (A) all cases 0 s to 5 s and below (B) case d1/4, 0 s to 30 s.

Figure 6. Dimensionless average vertical velocity distribution vx/v1 as function of y/d1.

should not be interpreted as an actual boundary layer. It was more likely an effect of the truncated kernel domain due to the lack of SPH nodes outside the boundary. Considerable research has been devoted to this topic and a possible solution is the use of a different boundary condition such as the ghost particle [42] , the repulsive particle [36] or the dynamic particle method [43] . Furthermore, the various density filters and kernel and kernel gradient correction methods proposed in literature (e.g. [44] ) may also be applied to reduce these unwanted effects.

In Figure 5, the dimensionless conjugate depth

To exclude the initial transient phase, data was collected in the time interval 2.5 s to 5.0 s for all cases and in the interval 15 s to 30 s for the coarsest case. Generally, coarser cases showed better agreement than finer cases. This behavior could be explained by the increased number of flow features resolved which as reported in [28] and [37] . Henceforth, data from the coarsest case

As mentioned in the introductory section, several authors have commented on the existence and the implication of large vortex structures and its effect on the free surface in the roller region. The vortex paring mechanism and the merging with the stationary vortex reported in [12] were not observed in present results. However, individual

Table 2. Statistical measurements A and P (Equation (19) and Equation (20)) of the conjugate depth d2 at location x = 1 m.

vortices translated with increasing size in the downstream direction in agreement with [12] . Figure 8 presents a snapshot of the flow structures found for the coarsest case where the blue lines represents streamlines. An active vortex is seen close to the jump toe which was translating downstream as well as a decaying vortex further downstream. The effects on the free surface of the vortices are marked in red and green. In Figure 9, the dimensionless averaged free surface profile

However, when investigating the dimensionless maximum standard deviation

A Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) analysis of the numerical depth at several positions downstream the jump toe was conducted. Figure 12 presents a typical output which can be compared with outcomes from similar analysis of experimental data, see for instance [20] . The spectral analysis showed dominant frequencies in the range 2 - 5 Hz and a significant peak at approximately 3.5 Hz which was in agreement with experimental observations, see [16] [18] [20] . Figure 13 presents the characteristic free surface fluctuation frequency

Figure 7. Longitudinal distribution of dimensionless average maximum velocity Vmax/v1 as function of dimensionless distance (x − x1)/d1 from the jump toe compared to empirical function by Chanson [9] .

Figure 8. Snapshot of vortices in the roller region downstream of the inlet(inlet position at x = 0 m) visualized by streamlines (blue) and free surface waves caused by active vortex (red) and decaying vortex (green).

Figure 9. A comparison of numerical and experimental results of the dimension less time average free surface profile η/d1 as function of dimensionless distance (x − x1)/d1 from the jump toe. Ref 1 [16] , ref 2 [18] , ref 3 [20] and ref 4 (present study).

Figure 10. A comparison of numerical and experimental results of the dimensionless standard deviation of the free surface actuations η'/d1 as function of dimensionless distance (x − x1)/d1 from the jump toe. Ref 1 [16] , ref 2 [18] , ref 3 [20] and ref 4 (present study).

dimensionless distance downstream the jump toe

4. Conclusion

Two dimensional hydraulic jumps have been investigated in present work using the Meshfree, Lagrangian particle based method Smoothed Particle Hydrodynamics. Four cases with different spatial resolution of the SPH

Figure 11. Numerical and experimental results of maximum dimensionless standard deviation (η'/d1)max as a function of the Froude number Fr1. References: Kucukali & Chanson [16] , Murzyn & Chanson [18] and Chachereau & Chanson [20] .

Figure 12. Typical output of the FFT analysis based on the SPH data. Here, case d1/4 at (x − x1)/d1 = 8:75.

particles were set up and as a general result more flow features were observed for the highly resolved cases. All cases showed a tendency to propagate in the upstream direction, which was assumed to be a consequence of the frictionless boundary condition used. Furthermore, a “artificial” boundary layer was observed close to the bottom which affected the incoming jet and was likely caused by the truncated kernel due to the lack of SPH nodes outside the boundary. The conjugate depth

Figure 13. Numerical and experimental results of free surface fluctuation frequency Ffs as function of the dimensionless distance downstream of the jump toe (x − x1) = d1. Reference: Chachereau & Chanson [20] .

Figure 14. Numerical and experimental results of free surface fluctuation Strouhal number Stfs as function of Froude number Fr1. References: Murzyn & Chanson [17] and Chachereau & Chanson [20] .

fairly good with experimental results even though the length of the jump was under predicted by roughly 25%. The maximum velocity in horizontal direction indicated a too dissipative zone past the roller which was likely caused by the viscosity model used. The investigation of vortex structures and its effect on the free surface showed generally good agreement for the mean and the standard deviation, even though the peak in the standard deviation occurred further downstream as compared to the experimental results. However, when comparing the maximum standard deviation as function of the Froude number a favorable result was obtained. The investigation of free surface fluctuation frequencies indicated a general over prediction of frequencies and that the longitudinal decay was not captured by the SPH model. Also, a minor under estimation of the Strouhal number was obtained even though the outcome was within the range of experiments. This work has shown that it is possible to investigate the dynamics of the internal velocity field and its impact on the free surface in a hydraulic jump using a relative simple and coarse SPH model. However, a future study focusing on highly refined cases and a more sophisticated viscosity model would be interesting.

Acknowledgements

The research presented was carried out as a part of “Swedish Hydropower Centre-SVC”. SVC has been established by the Swedish Energy Agency, Elforsk and Svenska Kraftnät together with Luleå University of Technology, KTH Royal Institute of Technology, Chalmers University of Technology and Uppsala University www.svc.nu.

Cite this paper

Patrick Jonsson,Pär Jonsén,Patrik Andreasson,T. Staffan Lundström,J. Gunnar I. Hellström, (2016) Smoothed Particle Hydrodynamic Modelling of Hydraulic Jumps: Bulk Parameters and Free Surface Fluctuations. Engineering,08,386-402. doi: 10.4236/eng.2016.86036

References

- 1. Lundström, T., Brynjell-Rahkola, M., Ljung, A.-L., Hellström, J. and Green, T. (2015) Evaluation of Guiding Device for Downstream Fish Migration with In-Field Particle Tracking Velocimetry and Cfd. Journal of Applied Fluid Mechanics, 8, 579-589.

- 2. Chanson, H. (2004) The Hydraulic of Open Channel Flow: An Introduction. Elsevier, Oxford.

- 3. Hager, W.H., Bremen, R. and Kawagoshi, N. (1990) Classical Hydraulic Jump: Length of Roller. Journal of Hydraulic Research, 28, 591-608.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00221689009499048 - 4. Chanson, H. and Brattberg, T. (2000) Experimental Study of the Air-Water Shear Flow in a Hydraulic Jump. International Journal of Multiphase Flow, 26, 583-607.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0301-9322(99)00016-6 - 5. Lin, C., Hsieh, S.-C., Lin, I.-J., Chang, K.-A. and Raikar, R.V. (2012) Flow Property and Self-Similarity in Steady Hydraulic Jumps. Experiments in Fluids, 53, 1591-1616.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00348-012-1377-2 - 6. Rajaratnam, N. (1965) The Hydraulic Jump as a wall Jet. Journal of Hydraulic Division, 91, 107-132.

- 7. Hornung, H.G., Willert, C. and Turner, S. (1995) The Flow Field Downstream of a Hydraulic Jump. Journal of Fluid Mechanics, 287, 299.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0022112095000966 - 8. Lennon, J.M. and Hill, D.F. (2006) Particle Image Velocity Measurements of Undular and Hydraulic Jumps. Journal of Hydraulic Engineering, 132, 1283-1294.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)0733-9429(2006)132:12(1283) - 9. Chanson, H. (2010) Convective Transport of Air Bubbles in Strong Hydraulic Jumps. International Journal of Multiphase Flow, 36, 798-814.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmultiphaseflow.2010.05.006 - 10. Kucukali, S. and Chanson, H. (2008) Turbulence Measurements in the Bubbly Flow Region of Hydraulic Jumps. Experimental Thermal and Fluid Science, 33, 41-53.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.expthermflusci.2008.06.012 - 11. Murzyn, F. and Chanson, H. (2008) Experimental Investigation of Bubbly Flow and Turbulence in Hydraulic Jumps. Environmental Fluid Mechanics, 9, 143-159.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10652-008-9077-4 - 12. Long, D., Rajaratnam, N., Steffler, P.M. and Smy, P.R. (1991) Structure of Flow in Hydraulic Jumps. Journal of Hydraulic Research, 29, 207-218.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00221689109499004 - 13. Mossa, M. (1999) On the Oscillating Characteristics of Hydraulic Jumps. Journal of Hydraulic Research, 37, 541-558.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00221686.1999.9628267 - 14. Mouazé, D., Murzyn, F. and Chaplin, J.R. (2005) Free Surface Length Scale Estimation in Hydraulic Jumps. Journal of Fluids Engineering, 127, 1191.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1115/1.2060736 - 15. Murzyn, F., Mouazé, D. and Chaplin, J. (2007) Air-Water Interface Dynamic and Free Surface Features in Hydraulic Jumps. Journal of Hydraulic Research, 45, 679-685.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00221686.2007.9521804 - 16. Kucukali, S. and Chanson, H. (2007) Turbulence in Hydraulic Jumps: Experimental Measurements. Technical Report CH62/07, Division of Civil Engineering, the University of Queensland, Brisbane.

- 17. Murzyn, F. and Chanson, H. (2009) Free-Surface Fluctuations in Hydraulic Jumps: Experimental Observations. Experimental Thermal and Fluid Science, 33, 1055-1064.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.expthermflusci.2009.06.003 - 18. Murzyn, F. and Chanson, H. (2007) Free Surface, Bubbly Flow and Turbulence Measurements in Hydraulic Jumps. Technical Report CH63/07, Division of Civil Engineering, the University of Queensland, Brisbane.

- 19. Chachereau, Y. and Chanson, H. (2011) Free-Surface Fluctuations and Turbulence in Hydraulic Jumps. Experimental Thermal and Fluid Science, 35, 896-909.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.expthermflusci.2011.01.009 - 20. Chachereau, Y. and Chanson, H. (2010) Free Surface Turbulence Fluctuations and Air-Water Flow Measurements in Hydraulic Jumps with Small Inflow Froude Numbers. Technical Report CH78/10, Division of Civil Engineering, the University of Queensland, Brisbane.

- 21. Violeau, D. (2012) Fluid Mechanics and the SPH Method: Theory and Applications. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199655526.001.0001 - 22. Scardovelli, R. and Zaleski, S. (1999) Direct Numerical Simulation of Free-Surface and Interfacial Flow. Annual Review of Fluid Mechanics, 31, 567-603.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev.fluid.31.1.567 - 23. Gomez-Gesteira, M., Rogers, B.D., Dalrymple, R.A. and Crespo, A.J. (2010) State-of-the-Art of Classical SPH for Free-Surface Flows. Journal of Hydraulic Research, 48, 6-27.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00221686.2010.9641242 - 24. Monaghan, J. (2012) Smoothed Particle Hydrodynamics and Its Diverse Applications. Annual Review of Fluid Mechanics, 44, 323-346.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev-fluid-120710-101220 - 25. Lucy, L.B. (1977) A Numerical Approach to the Testing of the Fission Hypothesis. The Astronomical Journal, 82, 1013-1024.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/112164 - 26. Gingold, R.A. and Monaghan, J.J. (1977) Smoothed Particle Hydrodynamics: Theory and Application to Non-Spherical Stars. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 181, 375-389.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/mnras/181.3.375 - 27. López, D., Marivela, R. and Garrote, L. (2010) Smoothed Particle Hydrodynamics Model Applied to Hydraulic Structures: A Hydraulic Jump Test Case. Journal of Hydraulic Research, 48, 142-158.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00221686.2010.9641255 - 28. Jonsson, P., Jonsén, P., Andreasson, P., Lundström, T. and Hellström, J. (2011) Smoothed Particle Hydrodynamics Modeling of Hydraulic Jumps. Proceedings of Particle-Based Methods II—Fundamentals and Applications, Barcelona, 26-28 October 2011, 490-501.

- 29. Federico, I., Marrone, S., Colagrossi, A., Aristodemo, F. and Antuono, M. (2012) Simulating 2D Open-Channel Flows through an SPH Model. European Journal of Mechanics—B/Fluids, 34, 35-46.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.euromechflu.2012.02.002 - 30. Chern, M.-J. and Syamsuri, S. (2013) Effect of Corrugated Bed on Hydraulic Jump Characteristic Using SPH Method. Journal of Hydraulic Engineering, 139, 221-232.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)HY.1943-7900.0000618 - 31. Padova, D.D., Mossa, M., Sibilla, S. and Torti, E. (2013) 3D SPH Modelling of Hydraulic Jump in a Very Large Channel. Journal of Hydraulic Research, 51, 158-173.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00221686.2012.736883 - 32. Liu, G. and Liu, M. (2003) Smoothed Particle Hydrodynamics: A Meshfree Particle Method. World Publishing Co. Pte. Ltd., Singapore.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1142/5340 - 33. Livermore Software Technology Corporation (LSTC) (2012) LS-DYNA Keyword User’s Manual, Version 971 R6.1.0, Vol. 1 and 2.

- 34. Monaghan, J.J. (1992) Smoothed Particle Hydrodynamics. Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics, 30, 543-574.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev.aa.30.090192.002551 - 35. Dalrymple, R. and Rogers, B. (2006) Numerical Modeling of Water Waves with the SPH Method. Coastal Engineering, 53, 141-147.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.coastaleng.2005.10.004 - 36. Monaghan, J. (1994) Simulating Free Surface Flows with SPH. Journal of Computational Physics, 110, 399-406.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1006/jcph.1994.1034 - 37. Jonsson, P., Jonsén, P., Andreasson, P., Lundström, T. and Hellström, J. (2015) Modelling Dam Break Evolution over a Wet Bed with Smoothed Particle Hydrodynamics: A Parameter study. Engineering, 7, 248-260.

http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/eng.2015.75022 - 38. Jonsén, P., Pålsson, B. and Häggblad, H.-Å. (2012) A Novel Method for Full-Body Modelling of Grinding Charges in Tumbling Mills. Minerals Engineering, 33, 2-12.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.mineng.2012.01.017 - 39. Crespo, A.J., Gómez-Gesteira, M. and Dalrymple, R.A. (2008) Modeling Dam Break Behavior over a Wet Bed by a SPH Technique. Journal of Waterway, Port, Coastal, and Ocean Engineering, 134, 313-320.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1061/(asce)0733-950x(2008)134:6(313) - 40. Stansby, P.K., Chegini, A. and Barnes, T.C.D. (1998) The Initial Stages of Dam-Break Flow. Journal of Fluid Mechanics, 374, 407-424.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0022112098009975 - 41. Jánosi, I.M., Jan, D., Szabó, K.G. and Tél, T. (2004) Turbulent Drag Reduction in Dam-Break Flows. Experiments in Fluids, 37, 219-229.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00348-004-0804-4 - 42. Randles, P. and Libersky, L. (1996) Smoothed Particle Hydrodynamics: Some Recent Improvements and Applications. Computer Methods in Applied Mechanics and Engineering, 139, 375-408.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0045-7825(96)01090-0 - 43. Crespo, A.J., Gómez-Gesteira, M. and Dalrymple, R.A. (2007) Boundary Conditions Generated by Dynamic Particles in SPH Methods. Computers, Materials and Continua, 5, 173-184.

- 44. Bonet, J. and Lok, T.-S. (1999) Variational and Momentum Preservation Aspects of Smooth Particle Hydrodynamic Formulations. Computer Methods in Applied Mechanics and Engineering, 180, 97-115.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0045-7825(99)00051-1