Journal of Modern Physics

Vol.07 No.15(2016), Article ID:71905,5 pages

10.4236/jmp.2016.715183

A Brief Note on the Clock-Hypothesis

Andreas Schlatter

Emeran AG, Küttigen, Switzerland

Copyright © 2016 by author and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY 4.0).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received: October 26, 2016; Accepted: November 7, 2016; Published: November 10, 2016

ABSTRACT

The clock-hypothesis is the fundamental assumption in the theories of relativity that duration, measured by clocks, is proportionate to the length of their respective world lines. Over the years, there have been contributions both, theoretical and experimental in nature, either confirming or questioning this hypothesis. We give an elementary model of two classes of clocks, which turn out to be relativistic clocks, and by doing so also offer a basis to see the limitations of the clock-hypothesis. At the same time, we find support for a hypothesis of L. de Broglie, regarding the existence of an internal clock of electrons. Our aim is to give a precise, yet accessible account of the subject.

Keywords:

Quantum Physics, Special Relativity, Schroedinger Evolution, de Broglie Internal Clock

1. Introduction

In his seminal work of 1905 [1] and again in a later paper [2] in 1907 A, Einstein originated the idea that clocks actually measure a duration, which is proportionate to the length of their respective world-lines1; an assumption, which is known today as the clock-hypothesis. This hypothesis underlies much of the geometric structure of the theories of relativity [3] . The clocks in the original work are no further specified other than they are ideal, point-like devices. Much work has been done since then on the topic of relativistic clocks, either by experimentally confirming the hypothesis through detection of time-dilation in specific clock-devices [4] [5] [6] [7] , or by showing limitations of the hypothesis including critique on the before mentioned experiments [8] [9] [10] . Experiments have so far mainly been based on either moving particles, like muons, or on atomic clocks, i.e. atoms emitting/absorbing light without recoil, possible due to the Mössbauer-effect [11] . Some recent work focuses on the fact that real clocks are never point-like entities and that consequently forces between its constituent parts or between different clock-devices can influence the duration-measurement at the quantum level. The considerable machinery of quantum-field theory in curved space-time is applied in [9] to describe gravitational effects on the clocks or in [10] to find e.g. an impact of particle-creation on the duration measurement. Other recent work centers around the question, which clock-devices qualify as relativistic clocks and which ones do not [12] .

In this short note, we will use a simple model, using elementary tools only, to describe two classes of clocks: moving particle-based clocks, especially electrons, and atomic clocks. We will show that they are indeed relativistic clocks and will rediscover a hypothesis by L. de Broglie [13] , concerning internal clocks of electrons. At the same time, we will be able to understand some of the critical arguments mentioned above. Our aim is to give a precise, yet accessible account of the subject.

2. Relativistic Clocks

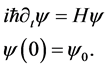

Let’s first consider a quantum system represented by a wave function  determined by the Schrödinger equation

determined by the Schrödinger equation

(1)

(1)

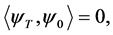

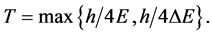

By the time-energy inequality and a result in [14] , there holds for the minimal time T until  evolves into an orthogonal state

evolves into an orthogonal state ,

,

(2)

(2)

In (2)  and

and  represent the first and second moment of the energy operator H. Let us assume that the system

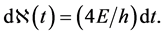

represent the first and second moment of the energy operator H. Let us assume that the system  is in its local rest-frame and ticks with frequency T2. By (2) it produces in an incremental time-step

is in its local rest-frame and ticks with frequency T2. By (2) it produces in an incremental time-step  the (incremental) number of flips (orthogonal states)

the (incremental) number of flips (orthogonal states)

(3)

(3)

To describe the first class of clocks based on (3) we think of the system  to be a particle with total (average) relativistic energy E and describe it in a semi-classical way. Then by (2) Equation (3) turns in the local rest frame into

to be a particle with total (average) relativistic energy E and describe it in a semi-classical way. Then by (2) Equation (3) turns in the local rest frame into

(4)

(4)

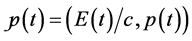

The energy E represents kinetic and inner energy, defining the time-component of the four momentum  along the world-line

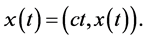

along the world-line  We can parametrise x by its write four-length s and (4) in covariant form by

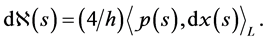

We can parametrise x by its write four-length s and (4) in covariant form by

(5)

(5)

The expression  denotes the four-scalar product. We will omit the subscript in the sequel. We can now write with

denotes the four-scalar product. We will omit the subscript in the sequel. We can now write with

There holds along any (time-like) world line

For electrons, satisfying

Therefore, by integration, we get for any distance

Equation (8) confirms that electrons can indeed act as relativistic clocks, ticking with an internal frequency of a multiple of

a result, which fits well in the discussion in e.g. [15] .

3The expectation value is taken with respect to the state

Another class of clocks consists of atomic devices, where

The most direct ansatz for a covariant formulation of (10) is to simply chose the length s of the world-line of the clock as the parameter. We get

If (11) is correct, then atomic clocks are indeed relativistic clocks as well. Let’s gather evidence for it and assume first that the clock (atom) is in transversal uniform motion relative to an observer at rest. We have

Therefore, we get for the frequency ν in the frame of the observer

where as usual

With

Hence

The effect of gravitational red-shift on atomic clocks (15) has indeed been observed as well [6] . Expressions (13) and (14) and their empirical verification are evidence that (11) is correct.

3. Some Observations

Experiments with the two kinds of clocks support the clock-hypothesis and our elementary model gives an accessible theoretical framework to explain it. The basis was that we managed to establish a relation (3) between the internal evolution of a system and the length of the world line it is supposed to pass through. While, of course, we compromised in principle by choosing a semi-classical treatment, it seems that, compared to moving particles, atomic clocks are even less ideal devices though, since they are not point-like, and Equation (11) only holds neglecting any real clock components other than the photon-emission/absorption. There might be effects on the photon by other parts of the clocks [9] or a more sophisticated description of the oscillator by a quantum-field might lead to particle-creation [10] . Qualitatively, we can see already from our model, e.g. by (4) or (10), that particle-creation must lead to a time-dilation in the order of magnitude of the energy of the created particles, which is no longer available to process the clock.

It is not obvious to see how systems, which cannot be brought into a covariant form of type (3)

could support the clock-hypothesis. Special relativity is the result of a conceptual merger of (classical) particle dynamics with electrodynamics. It is interesting to notice, that the clock-hypothesis is indeed best confirmed by devices, which are based on either of the two pillars: particle motion or electromagnetism. Systems, whose internal evolution base on other forces, like thermal energy, seem more resistant to confirm the hypothesis [12] .

More work will be done on the question of clocks in order to tackle the deeper issue, namely the one of the true nature of time.

Cite this paper

Schlatter, A. (2016) A Brief Note on the Clock-Hypothesis. Jour- nal of Modern Physics, 7, 2098-2102. http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/jmp.2016.715183

References

- 1. Einstein, A. (1905) Annalen der Physik, 17, 891-921.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/andp.19053221004 - 2. Einstein, A. (1907) Jahrbuch der Radioaktivität, 411-462.

- 3. Maudlin, T. (2012) Philosophy of Physics, Volume 1: “Space and Time”. Princeton University Press, Princeton.

- 4. Rossi, B. and Hall, D.B. (1941) Physical Review, 59, 223-228.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1103/PhysRev.59.223 - 5. Ives, H.E. and Stilwell, G. (1938) Journal of the Optical Society of America, 28, 215.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1364/JOSA.28.000215 - 6. Pound, R.V. and Rebka, G.A. (1959) Physical Review Letters, 3, 439-441.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.3.439 - 7. Hafele, J. and Keating, R. (1972) Science, 177, 168-170.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.177.4044.168 - 8. Bonnizoni, I. and Giuliani, G. (2000) The Interpretations by Experimenters of Experiments on “Time Dilation”: 1940-1970 ca. arXiv:physics/0008012 [physics.hist-ph].

- 9. Zych, M., Costa, F.M., Pikovski, I., Brukner, C. and Ralph, T.C. (2016) Journal of Physics: Conference Series, 723.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1088/1742-6596/723/1/012044 - 10. Ahmadi, M., Bruschi, D.E., Sabin, C., Adesso, G. and Fuentes, I. (2014) Scientific Reports, 4, Article ID: 4996.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/srep04996 - 11. Mössbauer, R. (1958) Zeitschriftfür Physik, 151, 124-143.

- 12. Borghi, C. (2016) Foundations of Physics, 46, 1374-1379.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10701-016-0030-y - 13. De Broglie, L. (1924) Annales de Physique, 3, 22.

- 14. Margolus, N. and Levitin, L.B. (1998) Physica D, 120, 188-195.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0167-2789(98)00054-2 - 15. Osche, G.R. (2011) Annales de la Fondation Louis de Broglie, 36, 61-71.

NOTES

1The notionoffour dimensional worldline was introducedonlylater in 1908 by H. Minkowski.

2We need, of course, an assumption on size to justify a singel time-parameter t and hence (1).