Pharmacology & Pharmacy

Vol.5 No.4(2014), Article ID:44823,7 pages DOI:10.4236/pp.2014.54048

Possibility of Drug-Drug Interaction in Prescription Dispensed by Community and Hospital Pharmacy

Huda Kafeel*, Ramsha Rukh, Hina Qamar, Jaweria Bawany, Mehreen Jamshed, Rabia Sheikh, Tazeen Hanif, Urooj Bokhari, Wardha Jawaid, Yumna Javed, Yamna Mariam Saleem

Faculty of Pharmacy, Jinnah University for Women, Karachi, Pakistan

Email: *huda_kafeel@hotmail.com

Copyright © 2014 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received 7 February 2014; revised 21 March 2014; accepted 7 April 2014

Abstract

Objective: To analyze the use of all subsidized prescription drugs including their use of drug combination generally accepted as carrying a risk of severe interactions. Methodology: In a cross sectional study, we analyzed all prescriptions (n = 1014) involving two or more drugs dispensed to the population (age range 4 - 85 years) from all pharmacies, clinics and hospitals. Data were stratified by age and sex, and frequency of common interacting drugs. Potential drug interactions were classified according to clinical relevance as significance of severity (types A: major, B: moderate, and C: minor) and documented evidence (types 1, 2, 3, and 4). Result and Discussion: The growing use of pharmacological agents means that drug interactions are of increasing interest for public health. Monitoring of potential drug interactions may improve the quality of drug prescribing and dispensing, and it might form a basis for education focused on appropriate prescribing. To make the manifestation of adverse interaction subside, management strategies must be exercised if two interacting drugs have to be taken with each other, involving: adjusting the dose of the object drug; spacing dosing times to avoid the interaction. The pharmacist, along with the prescriber has a duty to ensure that patients are aware of the risk of side effects and a suitable course of action they should take. Conclusion: It is unrealistic to expect clinicians to memorize the thousands of drug-drug interactions and their clinical significance, especially considering the rate of introduction of novel drugs and the escalating appreciation of the importance of pharmacogenomics. Reliable regularly updated decision support systems and information technology are necessary to help avert dangerous drug combinations.

Keywords:Drug-Drug Interaction; Adverse Drug Reaction; Polypharmacy

1. Introduction

Drug-drug interactions (DDIs) have received a great deal of recent attention from the regulatory, scientific, and health care communities worldwide [1] . A drug interaction is defined as the pharmacologic or clinical response to the administration of a drug combination differing from that anticipated from the known effect of the 2 agents [2] . A clinically significant interaction between 2 drugs is said to have occurred when the therapeutic or toxic effect of one drug is altered as a consequence of co-administration of another drug. Some knowledge of the pharmacological basis of how one drug may change the action of another is useful in obtaining those interactions that are wanted, as well as in recognizing and preventing those that are not [3] . There are different types of interaction. Interaction that may result in a change in the nature or type of response to a drug is pharmacodynamic interaction [2] . Pharmacokinetic interactions encompass alterations in ADME (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion). Pharmacokinetic DDIs are indirect in that the perpetrator either inhibits or induces the metabolic clearance of the substrate object drug which results in augment or reduces the clinical effect of object drug due to change in systemic plasma concentration [4] .

Pharmacoepidemiologic studies, mostly carried out in Europe and the Americas, have found varying rates of potential DDIs, ranging from 5% to 80% [5] -[8] . Factors that have shown consistent association with the presence of potential DDIs in previous studies included polypharmacotherapy [9] -[12] , age [2] [10] , gender, main diagnosis and medication and the number of physicians that a patient visits, [13] -[15] . Studies conducted in various mainly western countries on incidence and causes of prescribing potentially hazardous drug combinations in general practice [16] [17] and potential determinants of drug-drug interactions associated dispensing in community pharmacies [18] .

With present observational study, we evaluated the prevalence of drug-drug interactions among the dispensed medications in the vicinity of Karachi. We have utilized the database [19] to check the interactions and evaluated the risk as major, moderate and minor. And different factors that are significantly associated with the possibility of potential DDIs were also been study.

2. Methodology

In our cross sectional study, we analyzed prescriptions involving two or more drugs dispensed to the population (age range 4 - 85 years) from different areas of Karachi (n = 1014). The total study sample of 1014 prescriptions was randomly stratified by age group sex, and frequency of common interacting drugs, presence and severity of interactions. We have utilized the database to check drug-drug interactions from the drugs.com website as previously utilized by Stephany Duda in 2005 [20] .

We excluded incomplete prescriptions. Further we classified them on the basis of mechanism of interaction, severity of interaction as major, moderate and minor, presence of mono or Polypharmacy etc. All these data is gathered, analyzed and presented in the form of tables and graphs as frequencies and percentages. Significant associations are also analyzed by using standard statistical method on SPSS version 21 (Figure 1).

3. Results and Discussion

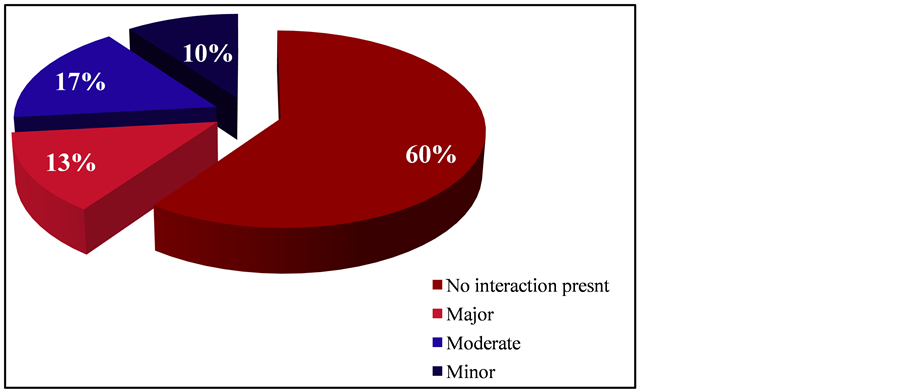

In a total of 1014 prescriptions we have found n = 608 (60%) prescriptions without any DDI and remaining n = 406 (40%) had at least one interacting combination with 13% major, 17% moderate and 10% minor interactions (Figure 2). Potential drug interactions were classified according to clinical relevance as significance of severity as (types A: major, B: moderate, and C: minor) and documented evidence (types 1, 2, 3, and 4)—for example, subtype C4 indicates an minor interaction with greater potential clinical relevance than that classified as subtype C1 and thus A4 subtypes were marked as lethal and life threatening to the patients and needs strict interventions. Clinically relevant minor potential drug interactions that could be controlled by adjusting the dose (type C) were found in 8.1%. Potential interactions that might have serious clinical consequences (type A) were found in 2.8% of the prescriptions. Of the potential type focal interactions were between potassium supplements and potassium sparing diuretics—a combination that may result in severe and even life threatening hyperkalaemia [21] [22] . With the increased availability of new drugs and their concomitant use with other drugs, there has been a rise in the potential for adverse drug interactions as demonstrated by the recent withdrawals of newly marketed drugs because of unacceptable interaction profiles. Therefore, the interaction potential of a novel compound has to be evaluated in detail, preliminary with preclinical in vitro and in vivo exercises at candidate selection and conti-

Figure 1. Flowchart representation of methodology.

Figure 2. Presence of potential drug-drug interactions.

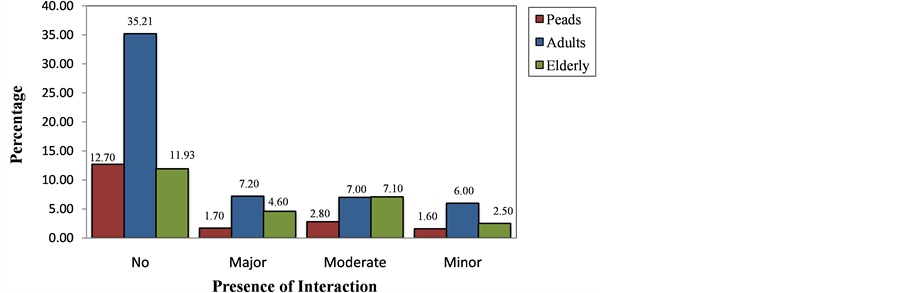

nuously followed up through preclinical and clinical development [21] . Different variables that are in close association with potential DDIs are summarized in Table 1. Poly pharmacy is use of multiple medications (as using ≥3 drugs) has been shown to drug-drug interactions particularly in the geriatric population [21] [23] . When presence of drug interactions were cross tabulated with age groups of patients, a highly significant relationship is found with p < 0.005 (chi-square test). Major interactions were found to be in prescription of patients age between 16 - 49 years (adult) with n = 202 interacting prescriptions (with 73 major, 68 moderate, 61 minor). Further possibility of interaction in Patients with ages between 50 years and above (elderly) n = 144 (with 47 major, 72 moderate, 25 minor) and prescription for pediatric patients n = 61 (with 17 major, 28 moderate, 16 minor) (Figure 3). The prevalence of drug-drug interactions (DDIs) in a geriatric population may be high because of Poly pharmacy. The most important mechanisms for drug-drug interactions are the inhibition or induction of drug metabolism, and potentiating or antagonism. Interactions involving a loss of action of one of the drugs are at least as frequent as those involving an increased effect [24] . Physicians with a responsibility for elderly people

Figure 3. Correlation of age with possibility of drug-drug interaction.

Table 1. Different variables associated with possibility of drug-drug interactions.

*Significant values (p < 0.05). **Highly significant values (p < 0.005). Chi-Square test of association is applied.

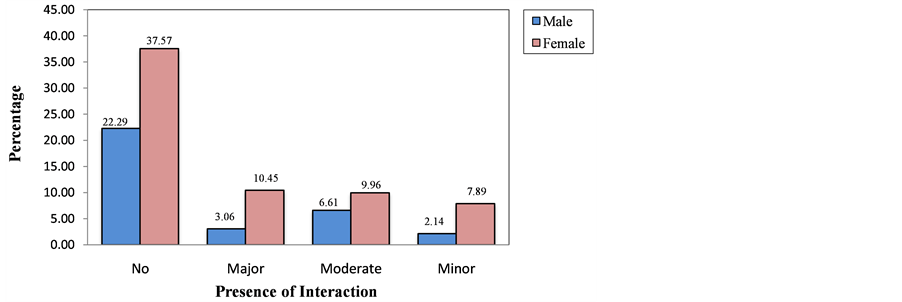

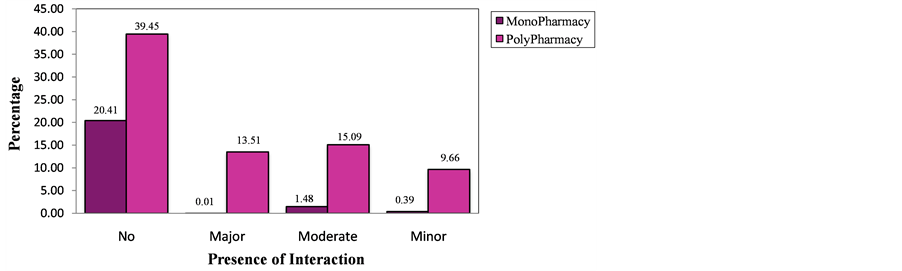

in an institutional setting should develop a strategy for monitoring their drug treatment. For those interactions that have come to clinical attention, it is important to review why they happened and to plan for future prevention. Not only prescriber but also dispenser has great responsibility regarding this age group [25] . Among female adult population rate possibility of interactions are high (n = 287) 42.96% as compare to male adults prescriptions. (n = 120) that is 36.68% within the gender (p < 0.005) (Figure 4). We targeted on three drug-drug interactions that involve usually used medications which turn out specific poisonous effects diagnosable with body information. Patients with polygenic disease treated with sulfonylureas, like glyburide, area unit in danger for hypoglycemia once taking sulphonamide antibiotics, partly as a result of these medication inhibit glyburide’s metabolism by the cytochrome P450 2C9 (CYP 2C9) catalyst system. digoxin toxicity will simply develop in patients at the same time treated with clarithromycin as a result of the latter inhibits P-glycoprotein, thirty one a multidrug efflux pump that promotes the renal clearance of digoxin [22] . Hyperkalaemia is common among patients treated with angiotensin-converting catalyst (ACE) inhibitors, and therefore the concomitant use of potassium-sparing diuretics will precipitate critical hyperkalaemia [24] . Polypharmacy was defined as using ≥3 drugs [21] . Among a total of 1014 prescriptions 788 prescriptions were of Poly pharmacy (77.7%) and among those, 388 prescriptions (48.9% of multi-drugs prescription) had interactive drugs. A total of 226 prescriptions were of 2 or >2 or <3 drugs and only 19 have interactions (p < 0.005) (Figure 5). Polypharmacy is highly prevalent in the elderly due to an increased number of co-morbid disease states that accompany aging. Hypertension is one common disease that can be challenging to treat in the elderly due to the body’s physiologic changes, potential risks for side effects, medication interactions, and decreased medication adherence [26] . Chronic diseases are common among the older population. The aging process results in altered metabolism and excretion of medications, and deficits in cognition and senses. Incidence of adverse drug reaction and interactions is increased with

Figure 4. Correlation of gender with possibility of drug-drug interaction.

Figure 5. Correlation of polypharmacy with possibility of drug-drug interaction.

polypharmacy. The risk for an adverse drug event is 13% with the use of two medications, but the risk increases to 58% for five medications [27] . This study demonstrates that a clinical pharmacist providing pharmaceutical care for primary care patients in all age groups can reduce inappropriate prescribing and possibly adverse drug effects without adversely affecting health related quality of life. Although the occurrence of interaction in females were not fatal to life but can be easily avoided if prescription were cross checked under the supervisions of clinical pharmacist. Computers are present in every modern dispensary and can reduce the likelihood of some drug-drug interactions [28] [29] . However, computers sometimes fail at this important task because of a lack of regular updates, or because recurrent warnings of an insignificant interactions (minor) nature fatigue the operators and lead them to override more significant ones. And DDI frequently lead to side effects in older adults [30] . Observance for early detection and management to avoid drug interaction were conjointly scrutinized and inspected from our information prescription. To subside the manifestation of adverse interaction, management strategies must be exercised if two interacting drugs has to be taken with each other, involves: Adjusting the dose of the object drug; Spacing dosing times to avoid the interaction. In some cases, once it’s necessary to administer interacting drug combinations, the interaction is managed through close laboratory or clinical observance for the proof of the patients; advance processed screening systems [29] [31] . The pharmacist, conjunction with the prescriber incorporates a duty to make sure that patients are attentive to the chance of side effects and an appropriate course of action ought to occur. With their elaborated data of medication, pharmacists have the flexibility to relate sudden symptoms experienced by patients to potential adverse effects of their drug medical aid. The apply in clinical pharmacy conjointly ensures that ADRs are decreased by avoiding medication with potential facet effects in prone patients. Thus, pharmacist incorporates a major role to play in relevancy hindrance, detection, and coverage adverse drug interactions [32] .

4. Conclusion

In a health care system, collaborative efforts of prescriber and dispenser are very important to make the therapy highly beneficial for the patients. The results of our study have quantified the issue which highlights that majority of interactions (around 17%) are those who were easily avoidable just by modifying dose or dosing intervals. Further use of database by professionals for rechecking prescriptions before dispensing should be encouraged and a pharmacist should not only have skills but also have authority to make necessary interventions in the prescription when required.

References

- Farkas, D., Shader, R.I., von Moltke, L.L. and Greenblatt, D.J. (2008) Mechanisms and Consequences of Drug-Drug Interactions. In: Gad, S.C., Ed., Preclinical Development Handbook: ADME and Biopharmaceutical Properties, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, 879-917. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/9780470249031.ch25

- Helms, R.A. and Quan, D.J. (2006) Text Books of Therapeutics Drug and Disease Management. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, Philadelphia.

- Ibrahim, Q.A. (2011) Hand Book of Drug Interaction and Mechanism of Interaction. Xilbris Corporation, Bloomington, 2-3.

- Piscitellu, S.C., Rodvold, K.A. and Pai, M.P. (2011) Drug Interaction in Infectious Disease. 3rd Edition, Springerscience + Business Media, Berlin, 1-11.

- Doubova, S.V., Reyes-Morales, H., del Pilar Torres-Arreola, L. and Suárez-Ortega, M. (2007) Potential Drug-Drug and Drug-Disease Interactions in Prescriptions for Ambulatory Patients over 50 Years of Age in Family Medicine Clinics in Mexico City. BMC Health Services Research, 7, 147. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-7-147

- Gagne, J.J., Maio, V. and Rabinowitz, C. (2008) Prevalence and Predictors of Potential Drug-Drug Interactions in Regione Emilia-Romagna, Italy. Journal of Clinical Pharmacy and Therapeutics, 33, 141-151. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2710.2007.00891.x

- Glintborg, B., Andersen, S.E. and Dalhoff, K. (2005) Drug-Drug Interactions among Recently Hospitalised Patients— Frequent but Mostly Clinically Insignificant. European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, 61, 675-681. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00228-005-0978-6

- Vonbach, P., Dubied, A., Krähenbühl, S. and Beer, J.H. (2008) Prevalence of Drug-Drug Interactions at Hospital Entry and during Hospital Stay of Patients in Internal Medicine. European Journal of Internal Medicine, 19, 413-420. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ejim.2007.12.002

- Jyrkkä, J., Enlund, H., Lavikainen, P., Sulkava, R. and Hartikainen, S. (2011) Association of Polypharmacy with Nutritional Status, Functional Ability and Cognitive Capacity over a Three-Year Period in an Elderly Population. Pharmacoepidemiology and Drug Safety, 20, 514-522. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/pds.2116

- Rosholm, J.U., Bjerrum, L., Hallas, J., Worm, J. and Gram, L.F. (1998) Polypharmacy and the Risk of Drug-Drug Interactions among Danish Elderly. A Prescription Database Study. Danish Medical Bulletin, 45, 210-213.

- Bjerrum, L., Søgaard, J., Hallas, J. and Kragstrup, J. (1998) Polypharmacy: Correlations with Sex, Age and Drug Regimen A Prescription Database Study. European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, 54, 197-202. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s002280050445

- Haider, S.I., Johnell, K., Thorslund, M. and Fastbom, J. (2007) Trends in Polypharmacy and Potential Drug-Drug Interactions across Educational Groups in Elderly Patients in Sweden for the Period 1992-2002. International Journal of Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics, 45, 643-653. http://dx.doi.org/10.5414/CPP45643

- Bjerrum, L., Lopez-Valcarcel B, G. and Petersen, G. (2008) Risk Factors for Potential Drug Interactions in General Practice. European Journal of General Practice, 14, 23-29. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13814780701815116

- Egger, S.S., Drewe, J. and Schlienger, R.G. (2003) Potential Drug-Drug Interactions in the Medication of Medical Patients at Hospital Discharge. European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, 58, 773-778.

- Janchawee, B., Wongpoowarak, W., Owatranporn, T. and Chongsuvivatwong, V. (2005) Pharmacoepidemiologic Study of Potential Drug Interactions in Outpatients of a University Hospital in Thailand. Journal of Clinical Pharmacy and Therapeutics, 30, 13-20. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2710.2004.00598.x

- Merlo, J., Liedholm, H., Lindblad, U., Björck-Linné, A., Fält, J., Lindberg, G. and Melander, A. (2001) Prescriptions with Potential Drug Interactions Dispensed at Swedish Pharmacies in January 1999: Cross Sectional Study. British Medical Journal, 323, 427. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.323.7310.427

- Chen, Y.F., Avery, A.J., Neil, K.E., Johnson, C., Dewey, M.E. and Stockley, I.H. (2005) Incidence and Possible Causes of Prescribing Potentially Hazardous/Contraindicated Drug Combinations in General Practice. Drug Safety, 28, 67- 80. http://dx.doi.org/10.2165/00002018-200528010-00005

- Becker, M.L., Kallewaard, M., Caspers, P.W., Schalekamp, T. and Stricker, B.H. (2005) Potential Determinants of Drug-Drug Interaction Associated Dispensing in Community Pharmacies. Drug Safety, 28, 371-378. http://dx.doi.org/10.2165/00002018-200528050-00001

- Jagarlapudi, S.A. and Kishan, K.R. (2009) Database Systems for Knowledge-Based Discovery. In: Chemogenomics, Humana Press, New York, 159-172. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-1-60761-274-2_6

- Duda, S., Aliferis, C., Miller, R., Statnikov, A. and Johnson, K. (2005) Extracting Drug-Drug Interaction Articles from MEDLINE to Improve the Content of Drug Databases. AMIA Annual Symposium Proceedings Archive, 216-220.

- Kuhlmann, J. and Mück, W. (2001) Clinical-Pharmacological Strategies to Assess Drug Interaction Potential during Drug Development. Drug Safety, 24, 715-725.

- Trumic, E., Pranjic, N., Begic, L. and Bečić, F. (2012) Prevalence of Polypharmacy and Drug Interaction among Hospitalized Patients: Opportunities and Responsibilities in Pharmaceutical Care. Materia Socio Medica, 24, 68-72.

- Koh, Y., Kutty, F.B.M. and Li, S.C. (2005) Drug-Related Problems in Hospitalized Patients on Polypharmacy: The Influence of Age and Gender. Therapeutics and Clinical Risk Management, 1, 39-48.

- Rosholm, J.U., Bjerrum, L., Hallas, J., Worm, J. and Gram, L.F. (1998) Polypharmacy and the Risk of Drug-Drug Interactions among Danish Elderly. A Prescription Database Study. Danish Medical Bulletin, 45, 210-213.

- Seymour, R.M. and Routledge, P.A. (1998) Important Drug-Drug Interactions in the Elderly. Drugs & Aging, 12, 485-494. http://dx.doi.org/10.2165/00002512-199812060-00006

- Cooney, D. and Pascuzzi, K. (2009) Polypharmacy in the Elderly: Focus on Drug Interactions and Adherence in Hypertension. Clinics in Geriatric Medicine, 25, 221-233. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cger.2009.01.005

- Prybys, K., Melville, K., Hanna, J., Gee, A. and Chyka, P. (2002) Polypharmacy in the Elderly: Clinical Challenges in Emergency Practice: Part 1: Overview, Etiology, and Drug Interactions. Emergency Medicine Reports, 23, 145-153.

- Rochon, P.A. (2013) Drug Prescribing for Older Adults.

- Johnston, R.T., de Bono, D.P. and Nyman, C.R. (1992) Preventable Sudden Death in Patients Receiving Angiotensin Converting Enzyme Inhibitors and Loop/Potassium Sparing Diuretic Combinations. International Journal of Cardiology, 34, 213-215.

- Wiltink, E.H. (1998) Medication Control in Hospitals: A Practical Approach to the Problem of Drug-Drug Interactions. Pharmacy World & Science, 20, 173-177.

- Bonetti, P.O., Hartmann, K., Kuhn, M., Reinhart, W.H. and Wieland, T. (2000) Potential Drug Interactions and Number of Prescription Drugs with Special Instructions at Hospital Discharge. Praxis (Bern 1994), 89, 182-189.

NOTES

*Corresponding author.