Pharmacology & Pharmacy

Vol.5 No.2(2014), Article ID:43001,8 pages DOI:10.4236/pp.2014.52028

Fixed Dose Combination of Magaldrate Plus Domperidone Is More Effective than Domperidone Alone in the Treatment of Patients with Gastroesophageal Reflux Symptoms: A Randomized Double-Blind Study

![]()

1Sección de Estudios de Posgrado e Investigación, Escuela Superior de Medicina del Instituto Politécnico Nacional, Mexico City, Mexico; 2Productos Medix, S.A. de C.V., México City, Mexico; 3Instituto Nacional de Enfermedades Respiratorias, Secretaría de Salud, Mexico City, Mexico.

Email: *juangreyesgarcia@gmail.com

Copyright © 2014 Shendel Nyx Rodríguez-Sánchez et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. In accordance of the Creative Commons Attribution License all Copyrights © 2014 are reserved for SCIRP and the owner of the intellectual property Shendel Nyx Rodríguez-Sánchez et al. All Copyright © 2014 are guarded by law and by SCIRP as a guardian.

Received November 22nd, 2013; revised January 15th, 2014; accepted February 10th, 2014

KEYWORDS

Antiacid; Domperidone; Gastroesophageal Reflux; Magaldrate; Prokinetic

ABSTRACT

Gastroeophageal reflux is a condition in which the acidified liquid content of the stomach backs up into the esophagus. The antiacid magaldrate and prokinetic domperidone are two drugs clinically used for the treatment of gastroesophageal reflux symptoms. However, the evidence of a superior effectiveness of this combination in comparison with individual drugs is lacking. A double-blind, randomized and comparative clinical trial study was designed to characterize the efficacy and safety of a fixed dose combination of magaldrate (800 mg)/domperidone (10 mg) against domperidone alone (10 mg), in patients with gastroesophageal reflux symptoms. One hundred patients with gastroesophageal reflux diagnosed by Carlsson scale were randomized to receive a chewable tablet of a fixed dose of magaldrate/domperidone combination or domperidone alone four times each day during a month. Magaldrate/domperidone combination showed a superior efficacy to decrease global esophageal (pyrosis, regurgitation, dysphagia, hiccup, gastroparesis, sialorrhea, globus pharyngeus and nausea) and extraesophageal (chronic cough, hoarseness, asthmatiform syndrome, laryngitis, pharyngitis, halitosis and chest pain) reflux symptoms than domperidone alone. In addition, magaldrate/domperidone combination improved in a statistically manner the quality of life of patients with gastroesophageal reflux respect to monotherapy, and more patients perceived the combination as a better treatment. Both treatments were well tolerated. Data suggest that oral magaldrate/domperidone mixture could be a better option in the treatment of gastroesophageal reflux symptoms than only domperidone.

1. Introduction

Gastroesophageal reflux is a common digestive disorder in which the stomach contents fall backwards from the stomach into the esophagus with or without regurgitation, which can result in acid damage to the esophageal mucosa. Pyrosis and regurgitation are the cardinal symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux, and they have a high positive predictive value for its diagnosis. Nevertheless, the disease can manifest more troublesome esophageal symptoms, such as dysphagia, hiccup, gastroparesis, or nausea among others; and extraesophageal or atypical symptoms including chronic cough, chest pain, asthma, hoarseness or sleep disturbances [1-3]. These troublesome symptoms have adverse impact on life quality of patients with more frequent or more severe symptoms, who have lower job productivity, eating problems and sleep disturbances [2-4]. In Latin America, it is estimated that 10% - 30% of the adult population experienced gastroesophageal reflux, in a similar way to Europe or North America [5-7].

The current medical management of gastroesophageal reflux includes the prescription of antiacids, sodium alginate, prokinetics, H2-receptor antagonists or proton pump inhibitors, coupled with lifestyle advice [8,9]. Acid suppression is the main objective to treat gastroesophageal reflux, and proton pump inhibitors are the first-line therapy for their potency. However, 20% - 42% of patients treated with proton pump inhibitors fail to response symptomatically to these drugs [10,11]. In patients who failed proton pump inhibitors twice daily, medical treatment is focused in treat disordered gastroesophageal motility including reduced lower esophageal sphincter pressure, ineffective esophageal motility and delayed gastric emptying by using prokinetics [12,13].

Domperidone is a dopamine antagonist with antiemetic and gastroprokinetic properties. It promotes gastric emptying of several types of liquid and solid meals [14] without interfering with response of antiparkinsonism treatment [15]. Furthermore, domperidone provides relief of symptoms in patients with dyspepsia or gastroesophageal reflux in controlled clinical trials [16,17] such as regurgitation [18]. Additionally, domperidone shows controversial results to improve the efficacy of omeprazole in gastroesophageal reflux [19,20], and it fails to show any additional benefit combined with ranitidine [21].

Although prokinetics agents are usually used in combination with acid suppression agents such as antiacids, the evidence of a superior efficacy of domperidone plus antiacids combinations is scarce but consistent. In these studies, domperidone increases the efficacy of magnesium hydroxide and alumminium hydroxide [22] and reduces the amount of alginate required in gastroesophageal reflux [17,23]. However, there are not comparative studies between domperidone alone and domperidone plus magaldrate, an antiacid effective in the treatment of gastroesophageal reflux [24].

For the reasons above described, the current study was focused to determine the efficacy and safety of chewable tablets of magaldrate plus domperidone in comparison with an equal formulation of domperidone alone, in patients with gastroesophageal reflux symptoms.

2. Patients and Methods

2.1. Subjects

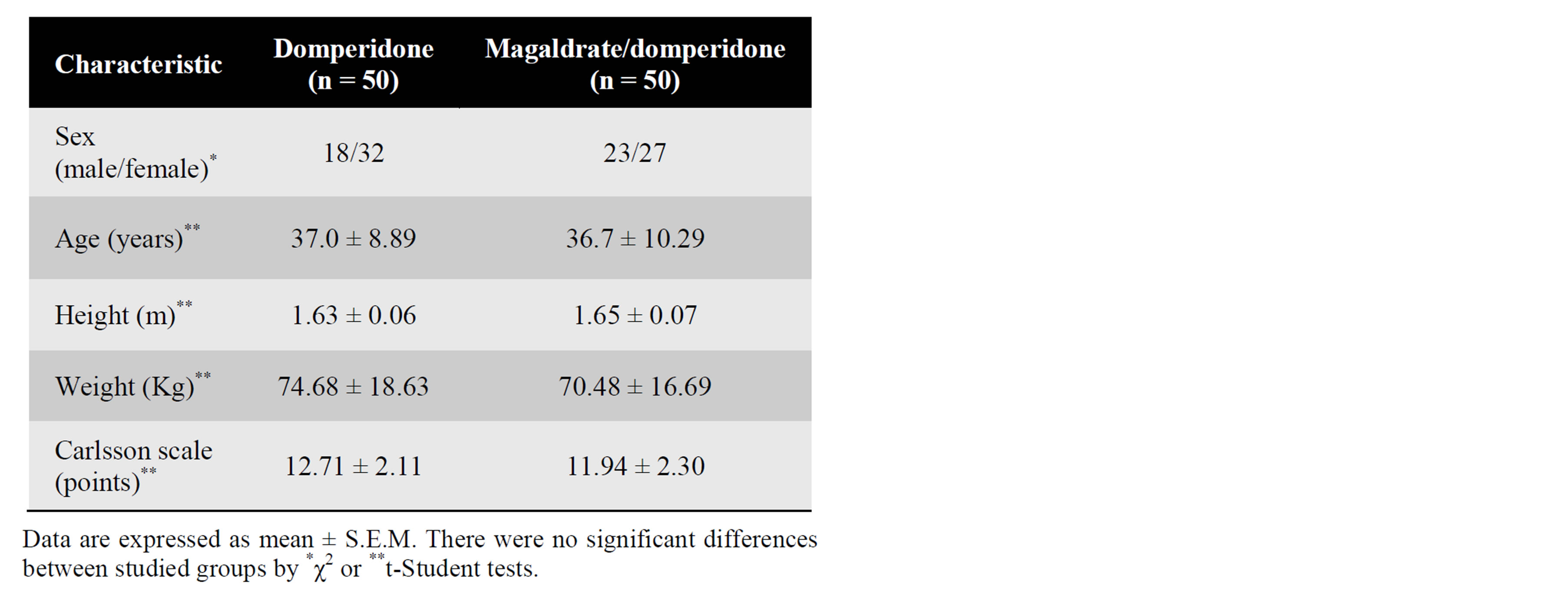

To determine whether magaldrate improved therapeutic profile of domperidone in patients with gastroesophageal reflux, one hundred volunteers (41 males and 59 females) were recruited to perform a double-blind, randomized and comparative clinical study. A comparison of the demographic data of the volunteers is shown in Table 1. All subjects included in the current study presented symptomatic gastroesophageal reflux disease according to Carlsson questionnaire [25] and were over 18 years old. In addition, the health status of patients was determined by medical history, clinical examination and suitable laboratory tests. If patients had alarm symptoms, a documented ulcer disease, gastric surgery, gastric cancer or severe concomitant medical conditions were excluded from the study. This study was carried out following the recommendations of the latest version of the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki-Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects [26]. All participants read the protocol, which was approved by the Institutional Research and Ethics Committees of the Hospital General Culiacán, “Dr. Bernardo J. Gastélum (Sinaloa, Mexico) and Mexican Federal Commission for Protection against Health Risks (CAS/ OR/01/CMN/103300410B0480-0017/2011), and provided written informed consent for their participation in the study.

2.2. Study Design

After obtaining written informed consent, patients were randomly allocated to one of 2 groups to receive a chewable tablet to a fixed dose either of domperidone alone (10 mg) or magaldrate/domperidone combination (800 mg/10 mg) before each meal, and one more before

Table 1. Demographic data.

going to bed, during 30 days. All chewable tablets were provided by Productos Medix, S.A. de C.V. (Mexico City, Mexico). Each gastroesophageal reflux symptom was evaluated at 0, 15 and 30 days of pharmacological treatment by patients using a six-point Likert scale that had the words: absent (0), very mild (1), mild (2), moderate (3), severe (4) and very severe (5). The symptoms assessed were esophageal (pyrosis, regurgitation, dysphagia, hiccup, gastroparesis, sialorrhea, globus pharyngeus and nausea) and extraesophageal (chronic cough, hoarseness, asthmatiform syndrome, laryngitis, pharyngitis, halitosis and chest pain), and the severity of gastroesophageal reflux was measured adding the score obtained in each symptom.

Moreover, a quality of life questionnaire was applied to patients consulting symptoms frequency, eating disorders, sleep disturbances, job productivity and other medications required at 0, 15 and 30 days of treatment. Frequency was evaluated by a four-point Likert scale that had the words: never (0), sometimes (1), frequently (2) and always (3). The life quality questionnaire has a maximum of 15 points. At the end of the treatment, a global satisfaction scale of pharmacological treatment was filled out by the patients. In addition, adverse events reported by patients were also recorded.

2.3. Data Analysis

Data were grouped by treatment. Potential differences of demographic data between groups were assessed by Student t-test or χ2 tests. Statistical analysis of the timecourse obtained from gastroesophageal reflux symptoms or life quality was performed by Kruskall-Wallis followed by the Dunn’s test. The score of gastroesophageal reflux symptoms or life quality was obtained adding the points of each item. Patient perception of global assessment of gastroesophageal reflux symptoms relief was evaluated by χ2 test. Differences were considered statistically significant when P ≤ 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Data

Demographic data on the patients are shown in Table 1. Domperidone alone and magaldrate/domperidone mixture groups were equilibrated regarding treatment, sex, age, weight, height and Carlsson scale values, and there were no violations to the protocol that may have interfered with the study variables. There were 59 female and 41 male and the mean ± standard deviation age was 36.8 ± 9.6 years with a range of 18 to 58 years. The predominant esophageal symptoms in patients were pyrosis in 100%, regurgitation in 93%, nausea in 67% and dysphagia in 42%, the rest of esophageal symptoms had a percentage below 40%. On the other hand, the main extraesophageal symptoms were chest pain with 43%, halitosis with 37% and pharyngitis with 33%, other extraesophageal reflux symptoms were present at less than 20% of patients.

3.2. Efficacy and Safety of Domperidone Alone against Magaldrate Plus Domperidone Combination

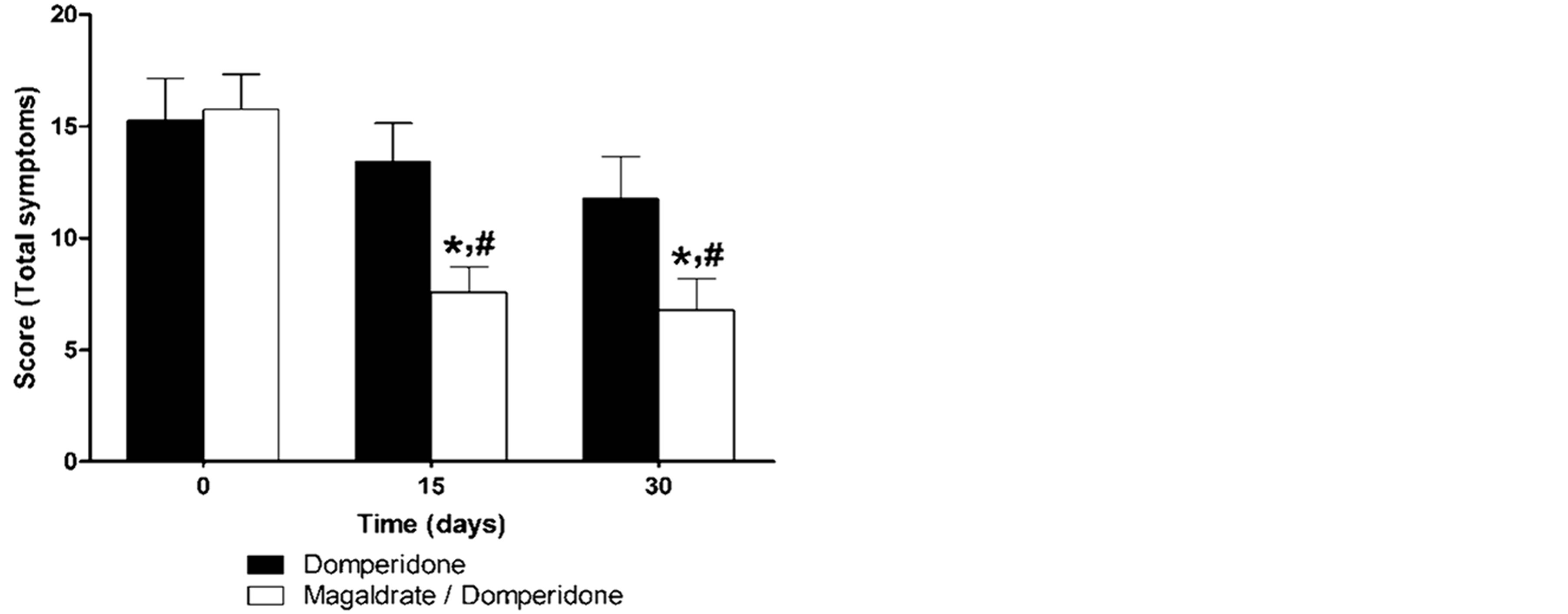

Baseline mean total reflux symptoms scores were 15.25 ± 1.90 for domperidone alone and 15.75 ± 1.57 for the mixture of magaldrate plus domperidone. Both treatments produced a gradual reduction of total reflux symptoms values in a dependent manner of time, but only the time course of the group treated with magaldrate plus domperidone showed a diminution significantly different (P ≤ 0.05 by Kruskall-Wallis, followed by the Dunn’s test) than its respective control group. In addition, magaldrate/domperidone group had a significantly superior efficacy to domperidone group at 15 and 30 days (Figure 1).

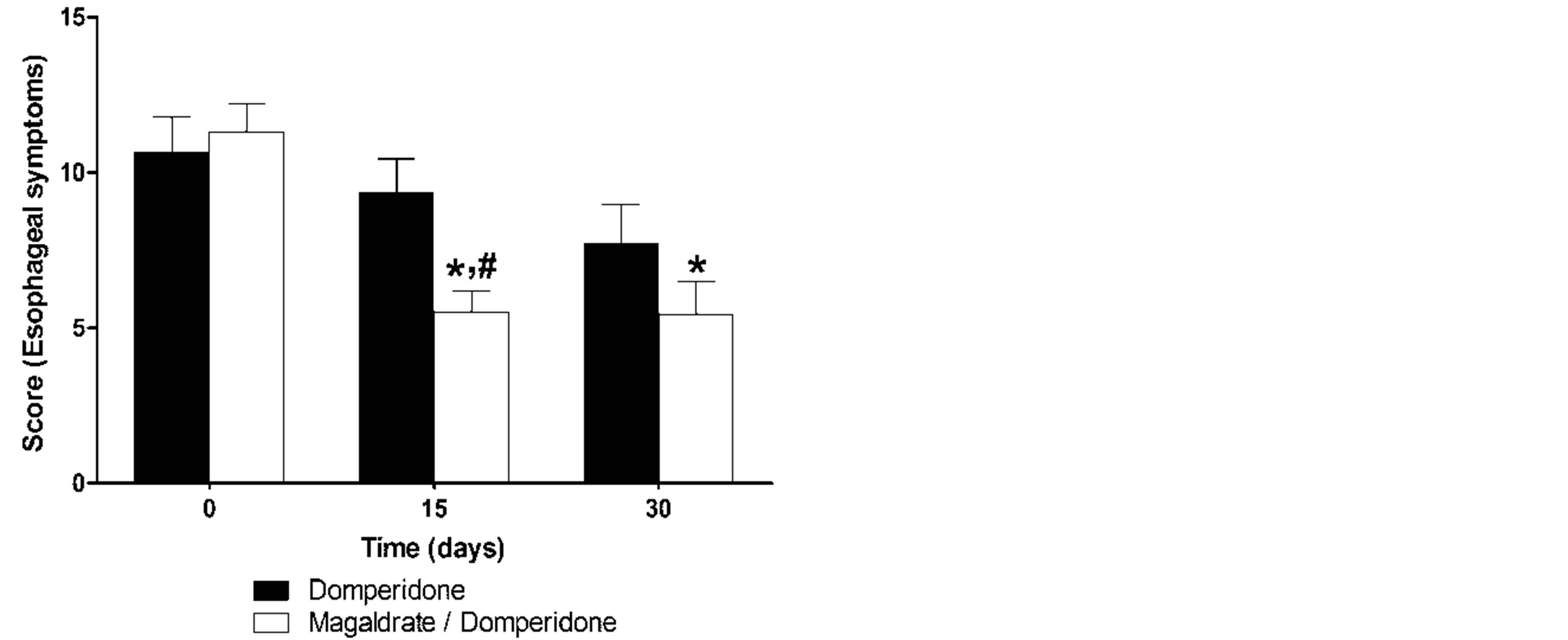

When the symptoms were sub-classified according with the symptom origin in esophageal and extraesophageal symptoms. The results of esophageal symptoms for the domperidone alone and magaldrate/domperidone groups were quite similar to those previously described in the analysis of total reflux symptoms. Again, domperidone group showed a tendency to decrease the symptoms, but it was not enough to reach a statistically

Figure 1. Time course of total gastroesophageal reflux symptoms obtained during thirty days in patients that received either domperidone alone or magaldrate/domperidone combination. Data are expressed as mean ± S.E.M. *Significantly different from respective control group at time 0 and #significnatly different from domperidone group at the same time (P ≤ 0.05), as was determined by KruskallWallis followed by the Dunn’s test.

difference, whereas the group of magaldrate/domperidone reduced in a significant manner (P ≤ 0.05) the esophageal symptoms at 15 and 30 days and was more effective than domperidone group at 15 days (Figure 2(a)). On the other hand, domperidone group did not show any tendency to improve the extraesophageal symptoms, but magaldrate/domperidone group significantly (P ≤ 0.05) decreased the extraesophageal symptoms more than 50% at 15 and 30 days (Figure 2(b)).

After symptom by symptom analysis, it was revealed that the tendencies showed by domperidone group in the previous results was due to that domperidone reduced significantly (P ≤ 0.05) the regurgitation symptom at 15

(a)

(a) (b)

(b)

Figure 2. Time course of esophageal (a) and extraesophageal (b) reflux symptoms obtained during thirty days in patients that received either domperidone alone or magaldrate/domperidone combination. Data are expressed as mean ± S.E.M. *Significantly different from respective control group at time 0 and #significnatly different from domperidone group at the same time (P ≤ 0.05), as was determined by Kruskall-Wallis followed by the Dunn’s test.

and 30 days (31.6% ± 10.4% and 44.4% ± 10.4%, respectively), as well as, nausea at 30 days (45.6% ± 14.8%), whereas, magaldrate/domperidone group improved mainly and in a significant manner (P ≤ 0.05) pyrosis (71.9% ± 7.3% and 81.3% ± 6.6%), regurgitation (56.7% ± 9.8% and 58.5% ± 6.5%) and nausea (55.8% ± 12.8% and 68.0% ± 14.1%) within esophageal symptoms, and laryngitis (86.3% ± 9.1% and 100%) and pharyngitis (75.0% ± 12.6% and 80.9% ± 13.2%) as extraesophageal symptoms at 15 and 30 days, respectively.

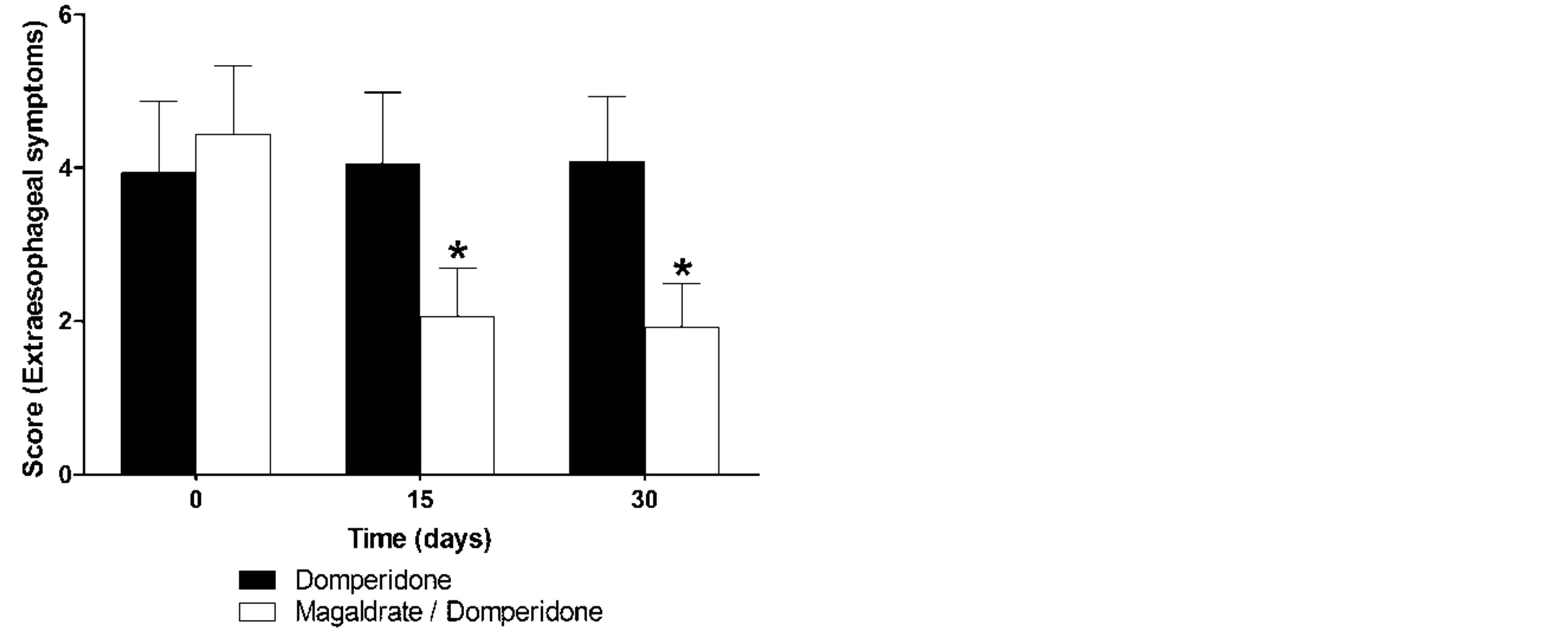

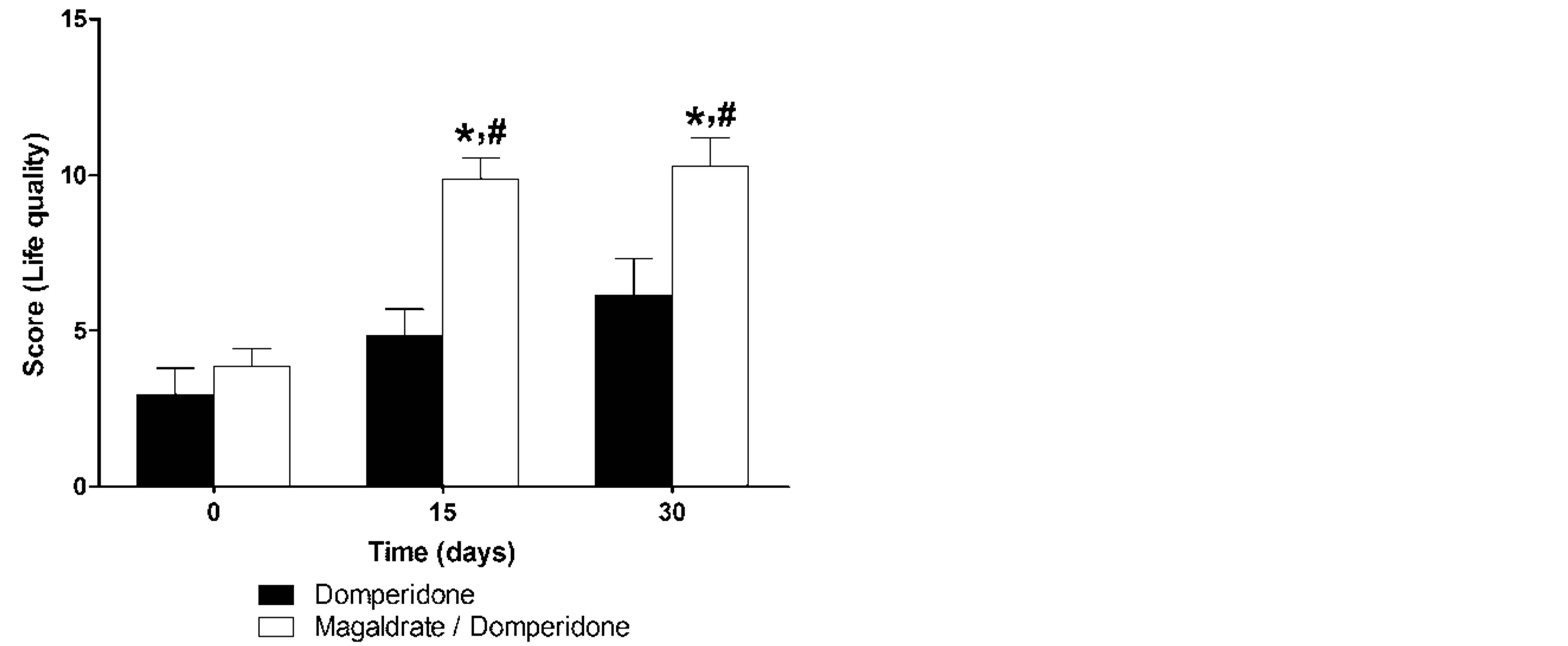

Respect to life quality questionnaire, domperidone group showed only a tendency to increase the life quality of patients (Figure 3); however, it was able to decrease statistically (P ≤ 0.05) eating disorders (49.7% ± 12.7%) at 30 days. On the contrary, magaldrate/domperidone group improved significantly (P ≤ 0.05) the life quality of patients respect to its own control and respect to domperidone group in both times of evaluation (Figure 3). Consequently, this group reduced in a significant manner (P ≤ 0.05) the symptoms frequency (51.9% ± 4.6% and 51.7% ± 6.3%), eating (45.8% ± 11.4% and 33.3% ± 11.4%) and sleep disturbances (35.3% ± 16.7% and 79.8% ± 7.4%) and requirement of other medications (75.0% ± 11.9% and 42.6% ± 17.4%); likewise, it also increased job productivity (53.8% ± 15.3% and 91.2% ± 6.1%) at 15 and 30 days.

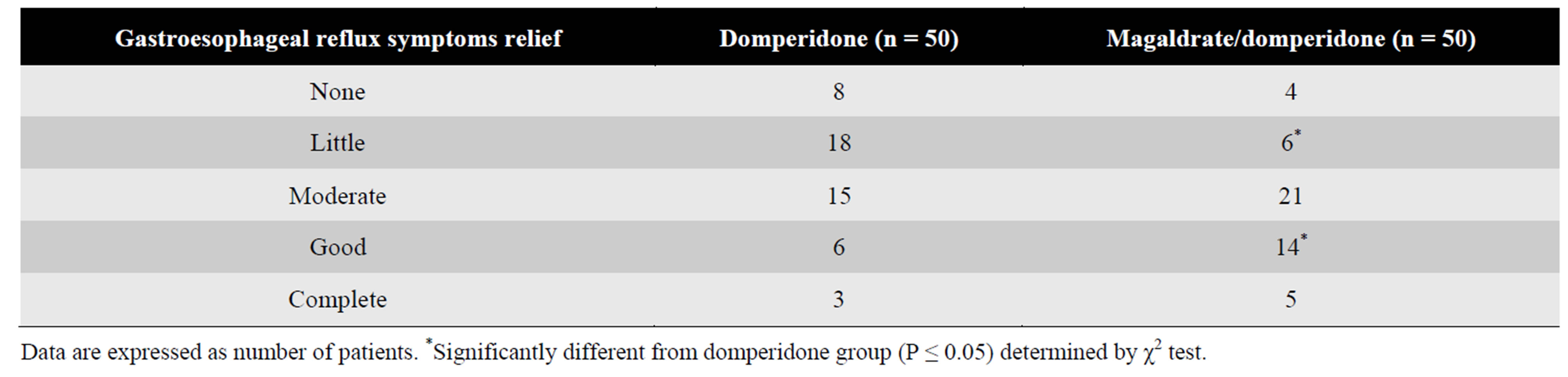

The global profile of pain relief perception favored to the group treated with the combination. A significant greater number of patients under treatment with magaldrate plus domperidone had a good perception of gastroesophageal reflux symptoms relief (n = 14) in

Figure 3. Time course of quality life reported during thirty days by patients that received either domperidone alone or magaldrate/domperidone combination. Data are expressed as mean ± S.E.M. *Significantly different from respective control group at time 0 and #significnatly different from domperidone group at the same time (P ≤ 0.05), as was determined by Kruskall-Wallis followed by the Dunn’s test.

comparison with patients treated with domperidone alone (n = 6) (Table 2).

Both treatments were well tolerated, since only six patients were withdrawn from the study, four for lack of efficacy and two for adverse events. A subject in the domperidone alone group was withdrawn for emesis and three for lack of efficacy, whereas that in the magaldrate/domperidone group was withdrawn a subject for mastalgia and galactorrhea and one more for lack of efficacy. Other adverse events reported by patients were mild, including two events of headache and one of diarrhea in the domperidone group, and two of dizziness, one of allergic rhinitis and one of constipation in the combination group.

4. Discussion

Domperidone is a peripheral dopamine D2-receptor antagonist, commonly used to treat regurgitation and vomiting due it increases motility and gastric emptying and decreases postprandial reflux time. However, the evidence of its efficacy in the treatment of gastroesophageal reflux symptoms continues being scarce and questioned, mainly in infants and children [27].

In this study, oral administration of chewable tablets of 10 mg domperidone four times each day during 30 days, reduced in a significant manner regurgitation and nausea esophageal symptoms, as well as, eating disorders. Notwithstanding, it only showed a tendency of improvement in the global gastroesophageal reflux symptoms or the total life quality score. Our data agree with a previous study performed in 23 patients over 8 weeks demonstrated that domperidone is superior to placebo in reducing regurgitation, but had not effect on the incidence of heartburn or on healing of the esophageal mucosa [18]. Similarly, Clara found in thirty-two children aged 2.5 months to ten years with chronic regurgitation and vomiting diagnosed clinically that 0.6 mg/Kg domperidone three times a day improved symptoms in a good or excellent manner in 93% of the patients compared with 33% of the controls [28]. In the same way, a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial performed in fortyseven children with excessive regurgitation and vomiting associated to gastroesophageal reflux showed that 0.5 mg/kg domperidone abolished completely vomiting in 75% of patients, compared with 43% in the metoclopramide group and 7% in the placebo group after 2 weeks of treatment [29]. On the contrary, Carrocio et al. reported that 0.3 mg/Kg domperidone was no significant different to placebo, after eight weeks of treatment, in the degree of improvement of pH metric variables of pediatric patients with severe gastroesophageal reflux [22]. Summarizing, domperidone seems to improve regurgitation and vomiting of gastroesophageal reflux symptoms, but fails in reduce other symptoms or modify pH values. For this reason, it is probable that domperidone mainly exerts its activity regulating disordered gastroesophageal motility [12,13,17].

On the other hand, the mixture of 10 mg domperidone/800 mg magaldrate produced a better therapeutic profile to significantly increase the quality of life and to reduce the intensity of gastroesophageal reflux symptoms respect to domperidone group. In line with these results, a previous randomized double blind clinical trial showed the existence of an additive effect between domperidone and omeprazole, since the combination was superior in efficacy respect to monotherapy with omeprazole in sixty dyspeptic patients with heartburn and/or regurgitation that received the treatments for 2 weeks [19]. Although, other studies point out that domperidone is not able to improve the efficacy of omeprazole [20] or ranitidine [21] in the treatment of esophageal reflux. Independently to the above described studies, domperidone and antiacid combinations seem to give results more consistent and they are according with the current study. So, a doubleblind randomized study showed that domperidone plus magnesium hydroxide and aluminium hydroxide was superior to domperidone plus alginate, domperidone alone or placebo in the control of gastroesophageal reflux symptoms in 80 children treated for 8 weeks [22]. Moreover, in a 4-week study in 22 patients with reflux esophagitis was demonstrated that domperidone reduced the amount of alginate-antiacid required when compared

Table 2. Patient’s perception about gastroesophageal reflux symptoms relief at the end of treatment.

with placebo [17,23]. Results suggest that the combination of domperidone/magaldrate is better in gastroesophageal reflux symptoms relief than domperidone alone. It is fair to say that, although the literature suggests that domperidone may improve the efficacy of antiacids drugs to treat gastroesophageal reflux, the prescription of these combinations should be given carefully in patients with cardiovascular disorders and children, since recent evidence points out that domperidone prolongs QTc interval increasing the risk of sudden cardiac death [30,31].

The better therapeutic profile of domperidone/magaldrate combination therapy versus domperidone alone to increase life quality and reduce the intensity of gastroesophageal reflux symptoms could be related to the addition of the different action mechanisms of the drugs. In the case of domperidone, there is evidence that this drug increases the amplitude of esophageal motor function, enhances antral-duodenal contractions and coordinates peristalsis across the pylorus with the subsequent acceleration of gastric emptying [32], due it has a high affinity for gastrointestinal tissue and high concentrations of the drug are found in the esophagus, stomach, and small intestine [33]. Its prokinetic activity is mainly attributed to stimulation of gastrointestinal transit through antagonism of D2-dopamine receptors localized on post-synaptic cholinergic neurons [34]. In addition, domperidone exerts its antiemetic activity inhibiting the chemoreceptor trigger zone, which is on the blood side of the blood-brain barrier in the fourth ventricle [17]. On the other hand, the magaldrate efficacy in the treatment of gastroesophageal reflux could be mainly attributed to its ability to rise rapidly and consistently the intragastric pH [22,35]. However, other studies have reported that magaldrate is also able to inactivate pepsin and binding to bile acids and lysolecithin, aggressors in case of gastroesophageal reflux [35,36]. Furthermore, magaldrate activates other gastroprotective mechanisms, such as, increment in gastric mucus secretion [37], stimulation of endogenous prostaglandin E2 [38] and protection of gastric mucosa of lipid peroxidation [39].

5. Conclusion

In conclusion, the data suggest that the combination of magaldrate/domperidone produces a greater efficacy in the reduction of esophageal and extraesophageal reflux symptoms, as well as a better life quality and relief perception than domperidone alone, in patients with gastroesophageal reflux symptoms. Data indicate that the combination of magaldrate/domperidone could be a better option than domperidone alone in the treatment of gastroesophageal reflux symptoms, mainly in refractory patients to pump proton inhibitors without cardiovascular disorders. Notwithstanding, the main limitation of the current study is its sample size, so larger double-blind clinical trials are needed to confirm this possibility. Furthermore, this study was performed to determine the superior efficacy of magaldrate plus domperidone combination over domperidone, but it does not give evidence of action mechanism involved in the interaction. For this reason, it is lacking a pharmacodynamic clinic study to explain this issue.

Aknowledgements

Authors kindly akcnowlegde Productos Medix, S.A. de C.V., Mexico City, Mexico for the formulations provided for this study. This work is part of the M.Sc. thesis of Shendel Nyx Rodriguez-Sanchez.

Conflict of Interest

Authors declare that there is no any conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- S. J. Spechler, “Epidemiology and Natural History of Gastro-Oesophageal Reflux Disease,” Digestion, Vol. 51, No. 1, 1992, pp. 24-29. http://dx.doi.org/10.1159/000200911

- Y. K. Wang, W. H. Hsu, S. S. Wang, et al., “Current Pharmacological Management of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease,” Gastroenterology Research and Practice, Vol. 2013, 2013, Article ID: 983653.

- D. A. Revicki, M. Wood, P. N. Maton, et al., “The Impact of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease on Health-Related Quality of Life,” American Journal of Medicine, Vol. 104, No. 3, 1998, pp. 252-258. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0002-9343(97)00354-9

- J. Tack, A. Becher, C. Mulligan, et al., “Systematic Review: The Burden of Disruptive Gastro-Oesophageal Reflux Disease on Health-Related Quality of Life,” Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics, Vol. 35, No. 11, 2012, pp. 1257-1266. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2036.2012.05086.x

- R. C. Heading, “Epidemiology of Oesophageal Reflux Disease,” Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology Supplement, Vol. 168, 1989, pp. 33-37.

- H. B. El-Serag, S. Sweet, C. C. Winchester, et al., “Update on the Epidemiology of Gastro-Oesophageal Reflux Disease: A Systematic Review,” Gut, 2013, in Press. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2012-304269

- G. Salis, “Revisión Sistemática: Epidemiología de la Enfermedad por Reflujo Gastroesofágico en Latinoamérica,” Acta Gastroenterol Latinoam, Vol. 41, 2011, pp. 60-69.

- B. van Pinxteren, K. E. Sigterman, P. Bonis, et al., “ShortTerm Treatment with Proton Pump Inhibitors, H2-Receptor Antagonists and Prokinetics for Gastro-Oesophageal Reflux Disease-Like Symptoms and Endoscopy Negative Reflux Disease,” Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Vol. 11, 2010, Article ID: CD002095.

- J. P. Henry, A. Lenaerts and G. Ligny, “Diagnosis and Treatment of Gastroesophageal Reflux in the Adult: Guidelines Recommended by French and Belgian Consensus,” Revue Médicale de Bruxelles, Vol. 22, 2001, pp. 27-32.

- J. P. Moraes-Filho, “Refractory Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease,” Arquivos de Gastroenterologia, Vol. 49, No. 4, 2012, pp. 296-301. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0004-28032012000400012

- D. Sifrim and F. Zerbib, “Diagnosis and Management of Patients with Reflux Symptoms Refractory to Proton Pump Inhibitors,” Gut, Vol. 61, No. 9, 2012, pp. 1340- 1354. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2011-301897

- R. Fass, “Therapeutic Options for Refractory Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease,” Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Vol. 27, No. S3, 2012, pp. 3-7. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1746.2012.07064.x

- D. Ang, K. Blondeau, D. Sifrim, et al., “The Spectrum of Motor Function Abnormalities in Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease and Barrett’s Esophagus,” Digestion, Vol. 79, No. 3, 2009, pp. 158-168. http://dx.doi.org/10.1159/000210265

- A. Broekaert, “Effect of Domperidone on Gastric Emptying and Secretion,” Postgraduate Medical Journal, Vol. 55, 1979, pp. 11-14.

- I. Soykan, I. Sarosiek, J. Shifflett, et al., “Effect of Chronic Oral Domperidone Therapy on Gastrointestinal Symptoms and Gastric Emptying in Patients with Parkinson’s Disease,” Movement Disorders, Vol. 12, No. 6, 1997, pp. 952-957. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/mds.870120618

- J. A. Barone, “Domperidone: A Peripherally Acting Dopamine2-Receptor Antagonist,” Annals of Pharmacotherapy, Vol. 33, No. 4, 1999, pp. 429-440. http://dx.doi.org/10.1345/aph.18003

- M. C. Champion, M. Hartnett and M. Yen, “Domperidone, a New Dopamine Antagonist,” CMAJ, Vol. 135, 1986, pp. 457-461.

- J. E. Valenzuela, “Effects of Domperidone on the Symptoms of Reflux Esophagitis,” In: G. Towse, Ed., Progress with Domperidone, a Gastrokinetic and Anti-Emetic Agent, Royal Society of Medicine International Congress and Symposium Ser, No 36, The Royal Society of Medicine, 1981, pp. 51-56.

- S. Ndraha, “Combination of PPI with a Prokinetic Drug in Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease,” Acta Medica Indonesiana, Vol. 43, 2011, pp. 233-236.

- N. Hunchaisri, “Treatment of Laryngopharyngeal Reflux: A Comparison between Domperidone Plus Omeprazole and Omeprazole Alone,” Journal of the Medical Association of Thailand, Vol. 95, 2012, pp. 73-80.

- E. Masci, P. A. Testoni, S. Passaretti, et al., “Comparison of Ranitidine, Domperidone Maleate and Ranitidine + Domperidone Maleate in the Short-Term Treatment of Reflux Oesophagitis,” Drugs under Experimental and Clinical Research, Vol. 11, 1985, pp. 687-692.

- A. Carroccio, G. Iacono, G. Montalto, et al., “Domperidone Plus Magnesium Hydroxide and Aluminum Hydroxide: A Valid Therapy in Children with Gastroesophageal Reflux. A Double-Blind Randomized Study versus Placebo,” Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology, Vol. 29, No. 4, 1994, pp. 300-304. http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/00365529409094839

- J. N. Blackwell and R. C. Heading, “Effects of Domperidone on Lower Esophageal Sphincter Pressure and Gastroesophageal Reflux in Patients with Peptic Esophagitis,” Royal Society of Medicine International Congress and Symposium Series, Vol. 36, 1981, pp. 57-65.

- E. G. Giannini, P. Zentilin, P. Dulbecco, et al., “A Comparison between Sodium Alginate and Magaldrate Anhydrous in the Treatment of Patients with Gastroesophageal Reflux Symptoms,” Digestive Diseases and Sciences, Vol. 51, No. 11, 2006, pp. 1904-1909. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10620-006-9284-0

- R. Carlsson, J. Dent, E. Bolling-Sternevald, et al., “The Usefulness of a Structured Questionnaire in the Assessment of Symptomatic Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease,” Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology, Vol. 33, No. 10, 1998, pp. 1023-1029. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/003655298750026697

- World Medical Association Inc., “Declaration of HelsinkiEthical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects,” 2013. http://www.wma.net/en/30publications/10policies/b3/

- D. S. Pritchard, N. Baber and T. Stephenson, “Should Domperidone Be Used for the Treatment of Gastro-Oesophageal Reflux in Children? Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials in Children Aged 1 Month to 11 Years Old,” British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, Vol. 59, No. 6, 2005, pp. 725-729. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2125.2005.02422.x

- R. Clara, “Chronic Regurgitation and Vomiting Treated with Domperidone. A Multicenter Evaluation,” Acta Neurologica Belgica, Vol. 32, 1979, pp. 203-207.

- L. De Loore and H. Van Ravenstayn, “Domperidone Drops in the Symptomatic Treatment of Chronic Paediatric Vomiting and Regurgitation. A Comparison with Metoclopramide,” Postgraduate Medical Journal, Vol. 55, 1979, pp. 40-42.

- M. C. Vieira, N. I. Miyague, K. Van Steen, et al., “Effects of Domperidone on QTc Interval in Infants,” Acta Paediatrica, Vol. 101, No. 5, 2012, pp. 494-496. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1651-2227.2012.02593.x

- L. M. Hondeghem, “Domperidone: Limited Benefits with Significant Risk for Sudden Cardiac Death,” Journal of Cardiovascular Pharmacology, Vol. 61, No. 3, 2013, pp. 218-225. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/FJC.0b013e31827afd0d

- S. C. Reddymasu, I. Soykan and R. W. McCallum, “Domperidone: Review of Pharmacology and Clinical Applications in Gastroenterology,” The American Journal of Gastroenterology, Vol. 102, No. 9, 2007, pp. 2036- 2045. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01255.x

- J. M. Van Nueten, C. Ennis, L. Helsen, et al., “Inhibition of Dopamine Receptors in the Stomach: An Explanation of the Gastrokinetic Properties of Domperidone,” Life Sciences, Vol. 23, No. 5, 1978, pp. 453-457. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0024-3205(78)90152-2

- T. Takahashi, S. Kurosawa, J. W. Wiley, et al., “Mechanism for the Gastrokinetic Action of Domperidone. In Vitro Studies in Guinea Pigs,” Gastroenterology, Vol. 101, 1991, pp. 703-710.

- C. Baur, A. Becker, R. Linder, et al., “Neutralizing Capacity, Pepsin Inactivation and Binding to Bile Acids and Lysolecithin of the Antacid Magaldrate,” Arzneimittelforschung, Vol. 31, 1981, pp. 504-507.

- D. F. McCafferty and A. D. Woolfson, “A Comparative Assessment of a New Antacid Formulation Based on Magaldrate,” Clinical and Hospital Pharmacy, Vol. 8, No. 4, 1983, pp. 349-355.

- L. E. Borella, J. F. DiJoseph and G. N. Mir, “Cytoprotective and Antiulcer Activities of the Antacid Magaldrate in the Rat,” Arzneimittelforschung, Vol. 39, 1989, pp. 786- 789.

- C. Schmidt, B. Baumeister, J. Kipnowski, et al., “Magaldrate Stimulates Endogenous Prostaglandin E2 Synthesis in Human Gastric Mucosa in Vitro and in Vivo,” Hepatogastroenterology, Vol. 45, 1998, pp. 2443-2446.

- A. V. Patel, D. D. Santani and R. K. Goyal, “Antiulcer Activity and the Mechanism of Action of Magaldrate in Gastric Ulceration Models of Rat,” Indian Journal of Physiology and Pharmacology, Vol. 44, 2000, pp. 350- 354.

NOTES

*Corresponding author.