Theoretical Economics Letters

Vol.06 No.06(2016), Article ID:73040,4 pages

10.4236/tel.2016.66123

Revenue Sharing in a Sports League with an Open Market in Playing Talent: A Comment

Stefan Szymanski

School of Kinesiology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, USA

Copyright © 2016 by author and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY 4.0).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received: November 2, 2016; Accepted: December 24, 2016; Published: December 27, 2016

ABSTRACT

Szymanski [1] and Szymanski and Késenne [2] showed that, in the standard model of a sports league, gate revenue sharing will tend to increase competitive imbalance between weak and strong teams, a seemingly perverse result. Dobson and Goddard [3] claim that “this analysis is flawed. If the revenue function is specified appropriately, gate revenue sharing always reduces competitive inequality.” This comment points out the analytical error in their paper which leads to their erroneous conclusion. Once their error is corrected, it is shown that the earlier results stand.

Keywords:

Professional Team Sports, Revenue Sharing, Competitive Inequality

1. The Issue

Competitive balance is considered an important issue in sports league. Many people believe that in the absence of a sufficient degree of competitive balance among teams the outcome of league competition will become too predictable; fans will lose interest; and the league will collapse. Redistributing revenues from strong teams to weak teams is widely advocated for overcoming this problem. However, the effectiveness of these schemes depends crucially on the revenue sharing mechanism. In a series of papers Szymanski [1] , Szymanski and Késenne [2] and Szymanski [4] (henceforth “SK”) showed that in the standard theoretical model of sports league competition, gate revenue sharing (allocating a fixed percentage of ticket revenue to the visiting team) has the perverse effect of increasing competitive imbalance (I refer to this as the SK result).

Dobson and Goddard [3] (henceforth “DG”) claim that the SK result is a consequence of “an inappropriately specified revenue function”. SK assume that team revenues are a concave function of team win percentage, at first increasing and eventually decreasing. Win percentage in turn depends on the share of talent employed, and hence only relative shares matter. DG assume in addition that revenues are increasing in the absolute quantity of talent in the league, and they claim that adding this to model reverses the SK result. This comment shows that their results are in fact a consequence of an analytical error, and once the error is corrected, the SK result holds.

2. The Model and the Error

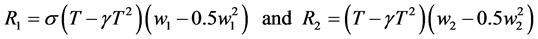

The standard model in the sports literature assumes that there are two profit maximizing teams that each chooses a quantity of talent which can be hired at a constant marginal cost per unit of talent. One team, the large market team, is assumed to have a larger revenue generating capacity for any given win percentage. DG (p412) define the revenue functions for teams 1 and 2 as  , where

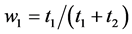

, where  is the total amount of playing talent in the league, w is win percentage,

is the total amount of playing talent in the league, w is win percentage,  is the parameter characterizing the larger market size supporting team 1 and

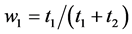

is the parameter characterizing the larger market size supporting team 1 and  is a parameter that captures decreasing returns to league quality. Win percentage is assumed to be a function of the share of total talent employed:

is a parameter that captures decreasing returns to league quality. Win percentage is assumed to be a function of the share of total talent employed:  and

and . Note that for either team win percentage is bounded between 0 and 1.

. Note that for either team win percentage is bounded between 0 and 1.

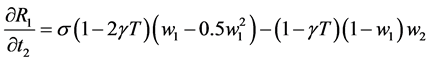

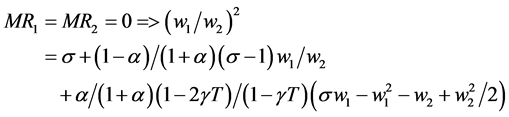

A condition for equilibrium is that the marginal revenue of talent of team 1 and team 2 are equalized. This condition can be defined as

(1)

(1)

α is the degree of revenue sharing;  implies no revenue sharing;

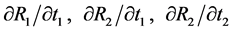

implies no revenue sharing;  implies equal revenue sharing. DG identify the four derivatives

implies equal revenue sharing. DG identify the four derivatives  and

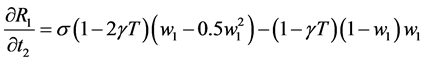

and  in the middle of page 412. It is in the middle two equations listed in the paper,

in the middle of page 412. It is in the middle two equations listed in the paper,  and

and  that the mistakes occur.

that the mistakes occur.

In DG the derivatives are stated as follows:

(2)

(2)

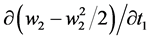

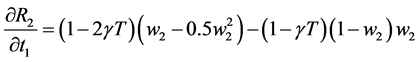

(3)

(3)

where .

.

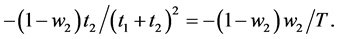

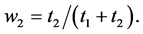

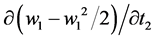

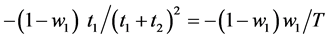

The second term in each of these equations is incorrect. The derivative we are looking for in the second term of  is

is  where

where

Likewise, the derivative we are looking for in the second term of

Correcting these errors, Equations (2) and (3) are restated as follows

These errors have important implication for the derivation of the equilibrium condition. After some manipulation it can be shown that DG Equation (3) should read

By inspection it should be clear that this formulation (3’) encompasses DG Equation (1), which emerges as a special case where absolute talent has no impact.

Once the correct specification (3’) is applied, the claims of the authors are no longer tenable. First, it is impossible to derive any general conclusions about the equilibrium values of

I have, however, attempted to find simulation solutions choosing particular values of

Thus the claim of the authors to have shown that “Competitive inequality is lower with equal revenue sharing

Intuitively the problem with the specification advanced by the authors is that both teams stand to gain by increasing total quality, but since the revenue of team 1 is larger than the revenue team 2 for any given value of own win percentage, team 1 typically has the greater incentive to invest in talent, and this turns out to be true even under revenue sharing.

Finally, it is worth commenting briefly on the authors assertion that the “If revenues depend upon relative team quality only, however, the equal revenue sharing solution

3. Conclusion

This comment addresses an error in the mathematical derivation of Dobson and Goddard [3] . These authors claimed to show that gate revenue sharing would increase competitive balance in a model in which demand was increasing in the aggregate quality of players. In fact, their result vanishes once the error has been corrected and the perverse result identified in Szymanski and Késenne [2] still holds. In the standard model, gate revenue sharing implies less, not more, competitive balance.

Cite this paper

Szymanski, S. (2016) Revenue Sharing in a Sports League with an Open Market in Playing Talent: A Comment. Theoretical Economics Letters, 6, 1337-1340. http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/tel.2016.66123

References

- 1. Szymanski, S. (2003) The Economic Design of Sporting Contests. Journal of Economic Literature, 41, 1137-1187.

https://doi.org/10.1257/jel.41.4.1137 - 2. Szymanski, S. and Késenne, S. (2004) Competitive Balance and Gate Revenue Sharing in Team Sports. The Journal of Industrial Economics, 52, 165-177.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0022-1821.2004.00220.x - 3. Dobson, S. and Goddard, J. (2014) Revenue Sharing in a Sports League with an Open Market in Playing Talent. Theoretical Economics Letters, 4, 410-414.

https://doi.org/10.4236/tel.2014.46052 - 4. Szymanski, S. (2004) Professional Team Sports Are Only a Game The Walrasian Fixed-Supply Conjecture Model, Contest-Nash Equilibrium, and the Invariance Principle. Journal of Sports Economics, 5, 111-126.

https://doi.org/10.1177/1527002503261485