Open Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology

Vol. 2 No. 4 (2012) , Article ID: 24461 , 3 pages DOI:10.4236/ojog.2012.24078

A review of conditions altering the permanent appearance of the vulva

![]()

1Women’s and Newborn Services, Royal Brisbane and Women’s Hospital, Herston, Australia

2University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia

Email: Ian_Jones@health.qld.gov.au

Received 16 August 2012; revised 14 September 2012; accepted 23 September 2012

Keywords: Vulvar Appearance; Congenital; Traumatic; Cultural; Iatrogenic

ABSTRACT

This article is aimed at providing information on variations in the clinical appearance of the vulva. The appearance of the vulva can be altered by reversible or permanent conditions both of which may result in minor or major changes. Reversible conditions include those associated with infections or acute trauma which results in distortion of the vulva. Some permanent changes are caused by life threatening conditions which are present at birth whereas others develop more slowly or as the result of a deliberate act either traditional female surgery or surgery performed by a registered medical practitioner. To the inexperienced practitioner changes from the normal vulvar appearance can be confusing. The aim of this article is to highlight and categorise changes that can affect the appearance of the vulva. Whatever the presentation the importance of obtaining a detailed history and performing an appropriate, sensitive and thorough examination can not be over emphasised.

1. INTRODUCTION

Variations in the clinical appearance of the vulvar can cause embarrassment for the woman and her physician. This article is aimed at providing information on variations in the clinical appearance of the vulva. It is important to be sensitive to the feelings of the woman (or child) and her family when discussing variations in anatomy irrespective of the cause of such change. Allowing the woman to indicate her own preference for describing how she sees her external genitalia is recommended. The need to enter the debate as to why any deliberate change, either minor or major has been made to the appearance of the vulva should be resisted.

Whenever a female of any age presents with a vulvar condition the importance of obtaining a detailed history and performing an appropriate, thorough and sensitive examination can not be over emphasised. An appropriate genital examination may require examination under general anaesthesia.

Of equal importance and before considering abnormal conditions normal variants need to be recognised. The range of normal appearance for the vulva and lower vagina is large. Such changes affect the mons pubis, labia, clitoris, vestibule and hymen. The size of these structures varies with age, ethnicity and parity. A degree of asymmetry is common and usually of no significance but asymmetry of the labia majora has been a presenting sign in a case of neurofibromatosis [1] hence each case needs to be carefully assessed.

2. CATEGORISATION

Conditions that may cause reversible changes to the appearance of the vulvar include those associated with infections, local reaction to drugs and chemicals and trauma, all of which may distort the vulva until resolved naturally or by treatment. Although changes to the appearance of the vulva occur as a result of tumours and ulcers treatment usually corrects such changes and so this group of conditions has been omitted from further study. It is recognised however that sometimes permanent scarring may result following these conditions.

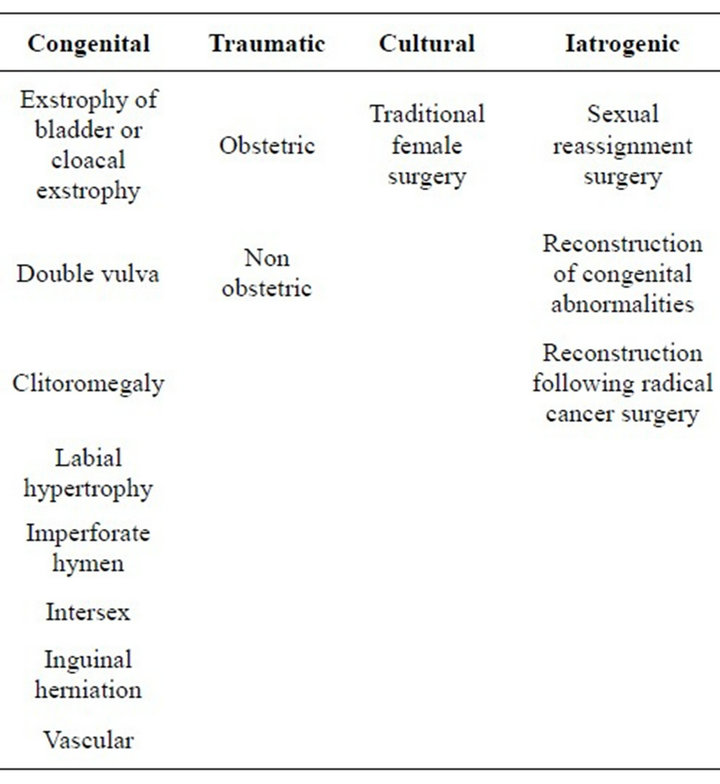

Causes of permanent changes to the vulva can be categorised as congenital, traumatic, cultural and iatrogenic. In turn each of these categories can be further subdivided (Table 1).

3. CONGENITAL

The complex congenital abnormalities of bladder exstrophy and cloacal exstrophy have a major affect on the appearance of the vulva. Bladder exstrophy involves an absence of the lower central anterior abdominal wall with the inside of the bladder and the urethra exposed onto the surface of the lower abdomen. There is diastasis of the symphysis pubis, the clitoris is separated into two

Table 1. Categories and subcategories for causes of permanent variations in appearance.

halves (bifid clitoris) and the labia minora displaced laterally [2].

Cloacal exstrophy has bladder exstrophy and large intestine presenting through the anterior abdominal wall defect, anal atresia, anomalous genitalia and an omphalocele.

Surgical repair of either bladder or cloacal exstrophy results in considerable scaring of the anterior abdominal wall and an improved but not entirely normal appearance of the vulvar.

The finding of a double vulvar is extremely rare and is associated with duplication of other portions of the reproductive tract, urethra, bladder and colon but with normal ovaries and kidneys [3]. The presence of cliteromegaly suggests excess male hormone either endogenous or exogenous however the possibility of life threatening congenital adrenal hyperplasia either the acute type seen in the newborn or the non-classic type seen in later life, must be seriously considered. The defective conversion of 17-hydroxyprogesterone to 11-deoxycortisol is the cause of congenital adrenal hyperplasia. In the newborn there is ambiguity of the female genitalia whereas at older age acne, hirsutism (including cliteromegaly, rugated and partly fused labia majora and a common urogenital sinus) and irregular menstruation are presenting symptoms and signs [4].

Labial hypertrophy or marked asymmetry of the labia minora can be a normal variant that may cause discomfort during coitus, walking or sitting down. Being able to show clinical photographs of such variation assists the woman to understand this issue.

An imperforate hymen may lead to cryptomenorrhoea, hematocolpus, hematometra, retrograde menstruation and acute urinary retention. Examination shows a bulge in the vestibule. Treatment is by surgical division of the thickened hymen thereby releasing the retained menstrual blood and relieving the introital distension.

The appearance of the vulva where a female fetus is exposed to raise androgen levels depends on when during intrauterine life this occurs. Early exposure results in complete external virilisation [5] with lesser effects resulting from lower androgen levels. Classifications of ambiguous external genitalia are based on anatomical and aetiological mechanisms. Patients with pure gonadal dysgenesis have a small phallus, poorly developed labia majora and fusion of the labioscrotal folds. With true hermaphrodites the appearance of the external genitalia varies considerably but most are raised as males because of the size of the phallus. Female pseudohermaphrodites have an enlarged clitoris, variable degrees of labial fusion and the urethral opening may not be distinct from the vagina [6]. Whatever ambiguity is found consultation with experts in this area of medicine is recommended.

Vascular tumours include benign hemangiomas and angiokeratomas and malignant epithelioid hemangioendothelioma and angiosarcoma. Tumors of lymphatic origin such as lymphangiomas are also described. Hemangiomas usually occur in infancy and childhood and are usually small. Varicose veins of the vulva are more often found in women with varicose veins in the legs. Vulval varicosities occur in four percent of women [7] and are common during pregnancy. In severe cases surgical management may be required.

An indirect inguinal hernia may distort the vulvar in the upper labia majora due to persistence of the equivalent of the male processus vaginalis. A mesothelial cyst anywhere along the line of the round ligament as it passes through the inguinal canal to its insertion in the upper labia majora is called a cyst in the canal of Nuck. Such cysts and hydroceles can if large enough cause a distortion in the labia majora.

4. TRAUMATIC

Obstetric trauma can cause minor or severe injury to any part of the vulvar. Severe injury results in tears of different shapes and size to labia, clitoris, perineum, urethra, anal sphincter and anus. Blood loss can be life threatening. Surgical repair of these injuries can distort the appearance of the vulvar. Not repairing transverse tears in the labia minora can result in excessively mobile skin which can cause pain or discomfort.

Non obstetric trauma may result in haematoma formation, lacerations, tears or a combination of the three. Mechanisms of injury include falling astride a firm object, consensual coitus, sexual assault, physical assault, burns and waxing. Genital piercings and shaving can also cause injury and infection.

5. CULTURAL

Within cultures of those who practice traditional female surgery phrases like cutting, ritual female surgery and female circumcision are more acceptable than female genital mutilation (FMG) which is the term used in Western societies. The basis for the World Health Organisation classification of FMG is the amount of vulvar tissue removed [8]. The more tissue removed increases the degree of distortion of the appearance of the vulva. In Type one FMG the prepuce is excised with or without removal of part or the entire clitoris. Type two FMG has the clitoris removed together with a partial or total excision of the labia minora. Type three FMG has part or all of the external genitalia removed with stitching or narrowing of the vaginal opening (infibulation). Type four FMG is unclassified but includes pricking, piercing or incising the clitoris and or labia; stretching of the clitoris and or labia; cauterisation by burning or the clitoris and surrounding tissue; scraping of tissue surrounding the vaginal orifice or cutting the vagina; introduction of corrosive substances or herbs into the vagina to cause bleeding or for the tightening or narrowing of the vagina; and any other procedure that falls under the definition given above.

Type three FMG procedures are thought to have been practiced by the Egyptian Pharaohs [9] and clitorectomy in Western medicine up to the late 1950’s to treat nymphomania, promiscuity and masturbation [10].

6. IATROGENIC

Male to female sexual reassignment surgery aims to create a neovagina and vulva. Scrotal skin is used to fashion labia but anteriorly the labia are separated by a band of skin from the filleted penis because of the need to preserve the blood supply of the penile skin and create a urethral opening. Once the collateral blood supply is secure this separation of the labia can be surgically reduced. There will however be no clitoris and the distribution of vulval hair will extend into the vagina unless there has been depilation of some type. In some cases efforts have been made to fashion labia majora and minora rather than labia majora alone.

Reconstruction of congenital abnormalities or defects from radical surgical treatment of vulvar cancer will have varying effects on the appearance of the vulvar depending on the extent of the repair.

7. DISCUSSION

At times physicians are required to examine women with genital piercings, genital tattoos and female circumcision. The need to enter the debate as to why any deliberate change, either minor or major has been made to the appearance of the vulvar should be resisted. Knowledge of both normal and altered vulvar anatomy assists the practitioner to manage difference and provide the best care for each patient.

This article highlights and categorises physical changes to the anatomy of the vulvar.

The importance of obtaining a detailed history and performing an appropriate, sensitive and thorough examination is stressed.

REFERENCES

- Friedrich, E.G. and Wilkinson, E.J. (1985) Vulvar surgery for neurofibromatosis. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 65, 135-138.

- Jayachandran, D., Bythell, M., Platt, M.W. and Rankin, J. (2011) Register based study of bladder exstrophy-epispadias complex: Prevalence, associated anomalies, prenatal diagnosis and survival. Journal of Urology, 186, 2056-2060. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2011.07.022

- Fanning, J. (1987) Double vulva. A case report. Journal Reproductive Medicine, 32, 297-300.

- Speiser, P.W. and White, P.C. (2003) Congenital adrenal hyperplasia. New England Medical Journal, 349, 776- 788. doi:10.1056/NEJMra021561

- Ridley, C.M. (2009) The vulva. In: Neill, S. and Lewis, F. Eds., 3rd Edition, Wiley-Blackwell, Oxford, 9.

- Ridley, C.M. (2009) The vulva. In: Neill, S. and Lewis, F. Eds., 3rd Edition, Wiley-Blackwell, Oxford, 11.

- Bell, D., Kane, P.B., Liang, S., Conway, C. and Tornos, C. (2007) Vulvar varices: An uncommon entity in surgical pathology. International Journal of Gynaecological Pathology, 26, 99-101.

- Gilbert, E. (1997) Female genital mutilation. Information for Australian health professionals. Royal Australian College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, Victoria, 8.

- Van Der Kwaak, A. (1992) Female circumcision and gender identity: A questionable alliance? Social Science and Medicine, 35, 777-787. doi:10.1016/0277-9536(92)90077-4

- Abdalla, R. (1982) Sisters in affliction. Zed Press, London.