International Journal of Communications, Network and System Sciences

Vol.09 No.10(2016), Article ID:70945,26 pages

10.4236/ijcns.2016.910033

A Receiver Structure for Frequency-Flat Time-Varying Rayleigh Channels and Performance Analysis

Xiaofei Shao, Harry Leib*

Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, McGill University, Montreal, Quebec, Canada

Copyright © 2016 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY 4.0).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received: June 28, 2016; Accepted: September 25, 2016; Published: September 28, 2016

ABSTRACT

This paper proposes a wavelet based receiver structure for frequency-flat time-vary- ing Rayleigh channels, consisting of a receiver front-end followed by a Maximum A-Posteriori (MAP) detector. Discretization of the received continuous time signal using filter banks is an essential stage in the front-end part, where the Fast Haar Transform (FHT) is used to reduce complexity. Analysis of our receiver over slow- fading channels shows that it is optimal for certain modulation schemes. By comparison with literature, it is shown that over such channels our receiver can achieve optimal performance for Time-Orthogonal modulation. Computed and Monte-Carlo simulated performance results over fast time-varying Rayleigh fading channels show that with Minimum Shift Keying (MSK), our receiver using four basis functions (filters) lowers the error floor by more than one order of magnitude with respect to other techniques of comparable complexity. Orthogonal Frequency Shift Keying (FSK) can achieve the same performance as Time-Orthogonal modulation for the slow-fading case, but suffers some degradation over fast-fading channels where it exhibits an error floor. Compared to MSK, however, Orthogonal FSK provides better performance.

Keywords:

Receiver Structure, Time-Varying Rayleigh Channels, Filter Banks, Fast Haar Transform

1. Introduction

Fueled by the increased interest in mobile communication for fast moving platforms [1] [2] , signal detection over fast-fading channels has become an important research area in the last decade [3] [4] . When signal fading is slow, the channel over at least one symbol interval can be assumed to be Additive White Gaussian Noise (AWGN), and a matched filter receiver front-end followed by symbol rate sampling provides good performance [5] . However, with fast fading the above matched filter method is suboptimal and more advanced techniques are needed [6] [7] .

Several methods of receiver design for fast-fading channels have been proposed [8] - [14] . Pilot symbol assisted modulation [8] adds known symbols in the transmitted signal, allowing the receiver to estimate the channel in order to establish an amplitude and phase reference for detection. This technique improves performance; however it lowers the effective bit rate, introduces delay, and requires buffer space at the receiver for channel interpolation. In [9] it is demonstrated that with fast fading, using a low-pass rectangular pilot filter produces an error floor, and more judiciously designed pilot filters are needed. In [10] , the authors show that processing more than one sample per symbol ensures robust performance in a fast-fading environment when Nyquist pulse shaping is used, at the expense of increased system complexity compared to traditional detection techniques. In line with such concept a receiver structure for a fading channel applying multisampling is derived in [11] .

Receivers for fast-fading channels based on filter banks are presented in [12] - [14] . In [12] , the authors demonstrate two types of receivers based on single-filter and double- filter. The single-filter receiver consists of two matched filters derived using a time-se- lective channel model which approximates the fading process by the first two terms of its Taylor expansion. The double-filter receiver consists of two matched filters and two modified matched filters derived using a time-selective channel model approximating the fading process by truncating the Taylor series to the third term. In [13] , the authors use specific basis functions as receiver filters for discretization. It is claimed that, by a moderate increase in complexity compared to a matched filter receiver, the performance is close to optimal except at very high Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR). Another method of designing front-end filters is presented in [14] , that employs the Karhunen-Loeve (KL) expansion [15] to approximate the autocorrelation function of the fading process by a finite dimensional separable kernel.

In this paper, we present a wavelet based receiver for frequency-flat time-varying Rayleigh channels, consisting of two parts: a front-end stage and a Maximum A-Post- eriori (MAP) detector. Discretization of the received continuous time signal is an essential function of the front-end stage, and for this task we employ the framework for discrete representation of continuous time signals from [16] that is well suited for fast-fading channels. Furthermore, the Fast Haar Transform (FHT) algorithm [17] is used to reduce complexity. Performance analysis and Monte-Carlo simulation results are presented for three binary modulation schemes: Time-Orthogonal modulation, Minimum Shift Keying (MSK) and Orthogonal Frequency Shift Keying (FSK).

2. System Model and Discrete Representation of Signals over Time-Varying Rayleigh Channels

2.1. System Model and Framework for Discrete Representation

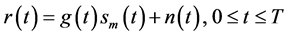

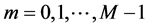

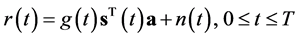

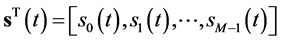

In this work, we consider a frequency-flat time-varying Rayleigh fading channel, with the complex baseband received signal expressed as [18]

(1)

(1)

where , (

, ( ) is transmitted with a-priori probability

) is transmitted with a-priori probability ,

,  is the fading process and

is the fading process and  is additive noise. The processes

is additive noise. The processes  and

and  are zero mean complex Gaussian and mutually independent. We assume that

are zero mean complex Gaussian and mutually independent. We assume that  and

and  have independent real and imaginary components that are stationary with same autocorrelation function. We also assume that

have independent real and imaginary components that are stationary with same autocorrelation function. We also assume that  is white with a single-sided power spectral density (PSD)

is white with a single-sided power spectral density (PSD) . We can express (1) in the form

. We can express (1) in the form

(2)

(2)

where ,

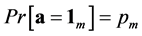

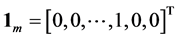

,  is a random M-dimensional vector with a-priori probability

is a random M-dimensional vector with a-priori probability , and

, and  having 1 as the mth component with the others being 0. Essentially, the vector

having 1 as the mth component with the others being 0. Essentially, the vector  selects the signal that is transmitted, and it is independent of

selects the signal that is transmitted, and it is independent of

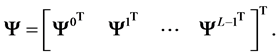

The process of discretization yields a finite dimensional vector of observables from a segment of a continuous time signal. We use the framework of [16] that is based on the KL expansion [15] . We start with the discretization of the message process

since

because

and

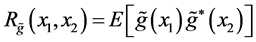

where yk are uncorrelated complex Gaussian variables, and the basis functions

In (6) we have

where

From the properties of the KL representation, we have

where

2.2. Examples for Specific Cases

Slow-Fading Channel with Linear Combination of Orthogonal Signals

The fading process

where

with

where

where

combinations of

Multiplying both sides of (15) by

because of (13). In matrix form, (16) becomes

where

with

We see that (17) is a matrix eigen-problem that can be solved by a multitude of methods.

Orthogonal signaling is a particular case where

Therefore

and the matrix

Substituting (20), (21) and (22) into (15) and using (19) yields

Frequency-Flat Fast-Fading Rayleigh Channel

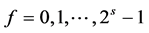

Consider a basis functions

where the coefficients

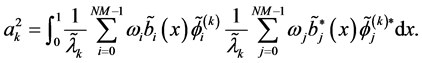

Substituting (25) into (7), we have

where

where

where

3. Receiver Structure

For convenience, we use the normalized time

where

must have a single-sided PSD of

Figure 1, consists of two parts: a receiver front-end performing the received signal discretization, with output

3.1. Receiver Front-End

Operating on

The basis functions

Figure 1. Receiver block diagram.

where

where

Using

where

Defining

with

where

with

In (38),

and

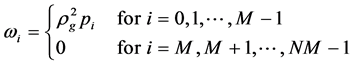

where

Next, we define

where

since

where

For conceptual simplicity, we take

where

when R is large, we can use the FHT algorithm that has a computational complexity

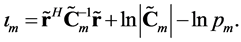

3.2. MAP Detector

The observable vector (31) is zero mean jointly Gaussian with conditional Probability Density Function (PDF)

where

with

The normalization factors ensuring

The structure of the MAP detector can be simplified by using the log-domain

Since

3.3. Structural Analysis of the Receiver over Slow-Fading Channels

In this case the fading process satisfies

and (35) is of the form

Hence, (36) becomes

Because

and (32) becomes

Therefore, we have

since

zeros, and assuming

we have

Furthermore, since

and substituting this into (7) yields

where

In ( [20] , p. 170], the authors present optimum receivers for slow-fading channels. From Figure 2, it is seen that in order to prove that our receiver can achieve optimality, we need to focus on two components: the quadratic form

Compared to ( [20] , p. 170], our receiver needs to satisfy the following two conditions to achieve optimality:

Condition 1

where

Condition 2

where

Figure 2. Simplified receiver block diagram.

and

with

From section B of the Appendix we have that satisfying

where

transmitted signals

and equiprobable

thogonal signaling in the normalized time setting, we have

From (73), it is seen that

1 and 2 hold, showing that our receiver with orthogonal signaling is optimal for slow- fading channels. Next we consider the performance over fast-fading channels.

4. Performance Analysis for Binary Modulation

4.1. Error Probability

From (53), using the log-likelihood metrics for hypotheses

Thus, we have the log-likelihood decision rule

Defining

Hermitian quadratic form where

where

where

aided by the residue theorem [23] , we have from (78)

for

for

In our work the PEP was calculated from (79) (80) using the MATLAB software package. We consider two fading autocorrelation functions: the Jakes’ model [24]

and autocorrelation function of a Butterworth filtered fading process [12]

where

propable

The covariance matrix

where, using (81) and (82), we have

4.2. Computer Simulations

Computer simulations in this paper employ the Monte-Carlo method and are implemented in the C language. We implemented the receiver of Figure 1 with three binary modulation schemes: Time-Orthogonal modulation, MSK, and Orthogonal FSK. The Bit Error Rate (BER) is estimated from at least 400 errors. In addition, we run at least 10,000 fading channel realizations to ensure accuracy. To emulate continuous time signals we massively oversample by using 4096 samples per symbol interval.

For the Jakes’ model, we use the Rayleigh fading channel simulator of [25] that is based on the sum-of-sinusoids algorithm, where we employ 50 sinusoids. Since we over-

sample, the Jakes’ model is expressed as

ples taken per symbol interval. For the Butterworth lowpass filtered fading process, each fading realization is generated by passing two white and independent real Gaussian processes through two identical third-order Butterworth filters as in [12] . The 3 dB bandwidth of these filters,

The SNR for simulations can be expressed as

After passing the received signal through an ideal band-limiting anti-aliasing filter, the power spectral density of

with

plex Gaussian with independent real and imaginary components which are stationary with same autocorrelation function, the variance of its real (or imaginary) component is given by [26]

The Time-Orthogonal modulation scheme [13] is defined by the waveforms

the MSK modulation scheme can be represented by

and Orthogonal FSK modulation is defined by

All three modulation schemes have the same average energy. According to our observations, we have that

Figure 3 illustrates the computed and simulated BER for Time-Orthogonal modulation with different values of K and

Figure 3. Time-orthogonal modulation, N = 4 and L = 16.

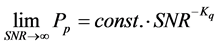

We can find analytically the diversity order that can be obtained with such a Time Orthogonal scheme by using Proposition 2 of [22] . Essentially the result of this proposition is

where for

Figure 6 illustrates the calculated and simulated BER for MSK modulation with different values of K and

Figure 4. Positive eigenvalues, N = 4, K = 4, L = 16 and fdT = 0.1.

Figure 5. Negative eigenvalues, N = 4, K = 4, L = 16 and fdT = 0.1.

error floor. Using

Figure 6. MSK modulation (Jakes), N = 4 and L = 64.

From Figure 6 and Figure 7, we see that, for MSK with

Figure 8 illustrates the computed and simulated BER for Orthogonal FSK. We see that for

Figure 7. MSK modulation (Butterworth), N = 4, L = 64.

5. Conclusions

This paper considers a wavelets based receiver structure for frequency-flat time-varying Rayleigh channels. The receiver consists of a front-end performing discretization of the received continuous time signal, and a MAP detector processing the outputs from the front-end. The fast Haar transform algorithm is used to reduce computational complexity. We present two conditions for achieving optimality over slow-fading channels, and demonstrate that using any orthogonal signaling scheme ensures optimality of our receiver in this case.

Numerical performance analysis and Monte-Carlo simulation results of three binary modulation schemes are presented for fast-fading Rayleigh channels. Among these schemes, Time-Orthogonal modulation performs best, and MSK worst. Increasing K, the number of basis function that the receiver uses, improves performance, but when K > 4 the performance is not improved further for Time-Orthogonal modulation and Orthogonal FSK using the Jakes’ fading model with

Figure 8. Orthogonal FSK modulation, N = 4 and L = 64.

floor by more than one order of magnitude compared to the double-filter receiver of [12] . Orthogonal FSK, which performs the same as Time-Orthogonal modulation over slow fading channels, provides a lower performance over fast time-varying fading channels.

Cite this paper

Shao, X. and Leib, H. (2016) A Receiver Structure for Frequency-Flat Time-Varying Rayleigh Channels and Performance Analysis. Int. J. Communications, Network and System Sciences, 9, 387-412. http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ijcns.2016.910033

References

- 1. Zhang, K., Zheng, Q., Chatzimisios, P., Xiang, W. and Zhou, Y. (2015) Heterogeneous Vehicular Networking: A Survey on Architecture, Challenges, and Solutions. IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials, 17, 2377-2396.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/COMST.2015.2440103 - 2. Ai, B., Cheng, X., Kürner, T., Zhong, Z.D., Guan, K., He, R.S., Xiong, L., Matolak, D.W., Michelson, D.G. and Briso-Rodriguez, C. (1992) Challenges toward Wireless Communications for High-Speed Railway. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems, 15, 2143-2158.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/TITS.2014.2310771 - 3. Hlawatsch, F. and Matz, G. (2011) Wireless Communications over Rapidly Time-Varying Channels. Academic Press, London.

- 4. Tsai, P., Chang, H., Hsieh, P., Hou, J. and Fan, K. (2010) Baseband Receiver Design for 3GPP Long Term Evolution Downlink OFDMA Systems under Fast-Fading Channels. 2010 IEEE Asia Pacific Conference on Circuits and Systems (APCCAS), Kuala Lumpur, 6-9 December 2010, 1207-1210.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/APCCAS.2010.5775016 - 5. Rappaport, T. and Fung, V. (1991) Simulation of Bit Error Performance of FSK, BPSK, and π/4 DQPSK in Flat Fading Indoor Radio Channels Using a Measurement-Based Channel Model. IEEE Transactions on Vehicular Technology, 40, 731-740.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/25.108384 - 6. Cavers, J.K. (1992) On the Validity of Slow and Moderate Fading Models for Matched Filter Detection of Rayleigh Fading Signals. Canadian Journal of Electrical and Computer Engineering, 17, 183-189.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/CJECE.1992.6592505 - 7. Bello, P.A. and Nelin, B.D. (1962) The Influence of Fading Spectrum on the Binary Error Probabilities of Incoherent and Differentially Coherent Matched Filter Receivers. IRE Transactions on Communications Systems, 10, 160-168.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/TCOM.1962.1088654 - 8. Cavers, J.K. (1991) An Analysis of Pilot Symbol Assisted Modulation for Rayleigh Fading Channels. IEEE Transactions on Vehicular Technology, 40, 686-693.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/25.108378 - 9. Fitz, M.P. (1992) Comments on Tone Calibration in Time Varying Fading. IEEE Transactions on Vehicular Technology, 41, 211-213.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/25.142779 - 10. Vietta, G.M. and Taylor, D.P. (1996) Multisampling Receivers for Uncoded and Coded PSK Signal Sequences Transmitted over Rayleigh Frequency-Flat Fading Channels. IEEE Transactions on Communications, 44, 130-133.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/26.486600 - 11. Dam, W.C. and Taylor, D.P. (1994) An Adaptive Maximum Likelihood Receiver for Correlated Rayleigh Flat-Fading Channels. IEEE Transactions on Communications, 42, 2684-2692.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/26.317409 - 12. Vietta, G.M., Mengali, U. and Taylor, D.P. (1994) Optimal Noncoherent Detection of FSK Signals Transmitted over Linearly Time-Selective Rayleigh Fading Channels. IEEE Transactions on Communications, 45, 1417-1425.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/26.649762 - 13. Hansson, U. and Aulin, T.M. (1999) Aspects on the Single Symbol Signaling on the Frequency Flat Rayleigh Fading Channel. IEEE Transactions on Communications, 47, 874-883.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/26.771344 - 14. Visintin, M. (2000) Waveforms for Fast Fading Channels. Electronics Letters, 36, 907-908.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1049/el:20000658 - 15. Van Trees, H.L. (2001) Detection, Estimation, and Modulation Theory, Part I. Wiley-Inter-science, New York.

- 16. Shao, X. and Leib, H. (2012) Discretization Methods of Continuous Time Signals over Frequency-Flat Fast-Fading Rayleigh Channels. 25th IEEE Canadian Conference on Electrical & Computer Engineering (CCECE), Montreal, 29 April-2 May 2012, 1-5.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/CCECE.2012.6334850 - 17. Kaiser, G. (1998) The Fast Haar Transform. Gateway to Wavelet. IEEE Potentials, 17, 34-37.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/45.666645 - 18. Proakis, J.G. and Salehi, M. (2008) Digital Communications. 5th Edition, McGraw-Hill, New York.

- 19. Phoon, K.K., Huang, S.P. and Quek, S.T. (2002) Implementation of Karhunen-Loeve expansion for Simulation Using a Wavelet-Galerkin Scheme. Probabilistic Engineering Mechanics, 17, 293-303.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0266-8920(02)00013-9 - 20. Simon, K.M. and Alouini, M. (2000) Digital Communication over Fading Channels. Wiley-Interscience, New York.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/0471200697 - 21. Turin, G.L. (1960) The Characteristic Function of Hermitian Quadratic Forms in Complex Normal Variables. Biometrika, 47, 199-201.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/biomet/47.1-2.199 - 22. Brehler, M. and Varansi, M.K. (2001) Asymptotic Error Probability Analysis of Quadratic Receivers in Rayleigh-Fading Channels with Applications to a Unified Analysis of Coherent and Noncoherent Space-Time Receivers. IEEE Transactions on Information Theory, 47, 2383-2399.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/18.945253 - 23. Evgrafov, M. (1966) Analytic Functions. Saunders Mathematics Books, Philadelphia.

- 24. Jakes Jr., W.C. (1974) Microwave Mobile Communications. Wiley, New York.

- 25. Alimohammad, A., Fard, S.F., Cockburn, B.F. and Schlegel, C. (2002) An Accurate and Compact Rayleigh and Rician Fading Channel Simulator. IEEE Vehicular Technology Conference, Singapore, 11-14 May 2008, 409-413.

- 26. Hida, T. and Hitsuda, M. (1993) Gaussian Processes. American Mathematical Society, Providence.

Appendix

A. Derivation of the Normalization Factors

We derive the factors

Since

where (96) is obtained using (33), and (97) is due to

The covariance of

Due to

where (101) is obtained using (33), and (102) is due to

B. Conditions 1 and 2

We show that satisfying (71) in Section 3.3 is sufficient for Conditions 1 and 2 to hold. Assume that

In this case, from (48) the covariance matrix can be expressed as

and hence, using (67),

where

The inverse of

where

where

Due to (67) and (71), (115) becomes

where the non-zero component of

When

Submit or recommend next manuscript to SCIRP and we will provide best service for you:

Accepting pre-submission inquiries through Email, Facebook, LinkedIn, Twitter, etc.

A wide selection of journals (inclusive of 9 subjects, more than 200 journals)

Providing 24-hour high-quality service

User-friendly online submission system

Fair and swift peer-review system

Efficient typesetting and proofreading procedure

Display of the result of downloads and visits, as well as the number of cited articles

Maximum dissemination of your research work

Submit your manuscript at: http://papersubmission.scirp.org/

Or contact ijcns@scirp.org