Wireless Sensor Network

Vol.09 No.07(2017), Article ID:78236,33 pages

10.4236/wsn.2017.97012

Media Access with Spatial Reuse for Cooperative Spectrum Sensing

Xiao Shao, Harry Leib

Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, McGill University, Montreal, Canada

Copyright © 2017 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY 4.0).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received: May 31, 2017; Accepted: July 28, 2017; Published: July 31, 2017

ABSTRACT

The increasing interest for wireless communication services and scarcity of radio spectrum resources have created the need for a more flexible and efficient usage of the radio frequency bands. Cognitive Radio (CR) emerges as an important trend for a solution to this problem. Spectrum sensing is a crucial function in a CR system. Cooperative spectrum sensing can overcome fading and shadowing effects, and hence increase the reliability of primary user detection. In this paper we consider a system model of a dedicated detect-and- forward wireless sensor network (DetF WSN) for cooperative spectrum sensing with k-out-of-n decision fusion in the presence of reporting channels errors. Using this model we consider the design of a spatial reuse media access control (MAC) protocol based on TDMA/OFDMA to resolve conflicts and conserve resources for intra-WSN communication. The influence of the MAC protocol on spectrum sensing performance of the WSN is a key consideration. Two design approaches, using greedy and adaptive simulated annealing (ASA) algorithms, are considered in detail. Performance results assuming a grid network in a Rician fading environment are presented for the two design approaches.

Keywords:

Cooperative Spectrum Sensing, Wireless Sensor Network, Media Access, Spatial Reuse

1. Introduction

With the rapid development of wireless technology and the growing number of innovative telecommunication services, the scarcity of radio spectrum resources has become a critical issue. Static allocation within the conventional spectrum management framework causes a bottleneck for efficient utilization of radio spectrum [1] . Relying on dynamic and opportunistic spectrum access technolo- gies, Cognitive Radio (CR) systems offer a promissing solution to spectrum shortage [2] . A typical example is the opportunistic use of the unused spectrum in TV broadcasting bands by IEEE 802.22 WRAN [3] systems. Another example is the concurrent operation of LTE and Wi-Fi in unlicensed bands via dynamic spectrum access techniques [4] [5] .

An important function in CR systems, that makes possible the discovery of free channels for opportunistic use, is spectrum sensing. Single user sensing performance is often compromised by multipath fading, shadowing, and uncer- tainty of background noise [6] . Sensing performance, however, can be improved by using Cooperative Spectrum Sensing [7] [8] . In such a scheme local spectrum measurement are performed at each sensing node, and a final decision is made after fusing the information from all cooperating sensors. Cooperative spectrum sensing provides better spatial coverage as well as multi-user diversity gains that improves the detection reliability, and helps to reduce the sensitivity require- ments of single detectors [9] .

A common realization method of cooperative spectrum sensing integrates the sensing function into secondary user (SU) terminals. However, a sufficient number of adequately located SUs is required to obtain accurate detection results. Furthermore, the SU cannot transmit data during the sensing period [10] [11] , reducing the user information transport efficiency, while still consuming baterry power. An alternative approach is External Sensing, which relies on a dedicated wireless sensor network (WSN) for spectrum sensing. A dedicated WSN can be deployed and controlled by the cognitive service provider, and can aid an SU to access the licensed spectrum. Such a scheme can cope with the hidden primary user problem, and guarantees robustness against model uncerta- inty induced by fading and path loss [12] . Moreover, in such a scheme sensors neither need to be mobile nor battery-powered, and the cost, complexity and power consumption of SU terminals can be reduced.

In this paper, we consider a Detect-and-Forward (DetF) distributed WSN for cooperative spectrum sensing. The operation of this scheme does not rely on centralized control requiring a separate decision fusion center. Hence better flexibility and scalability can be provided by such an approach [13] . However, a proper media access control (MAC) protocol is required to coordinate trans- missions between sensors in order to efficiently use resources and resolve contention. In an WSN, the most significant design constraint is usually the limited energy budget of a sensor node together with the requirement of net- work longevity [14] [15] . However, in our DetF WSN sensors are assumed to be fixed in the deployment region and do not depend on limited battery power. Thus, spectrum efficiency and interference, instead of energy efficiency, become the primary issues. Another special part of our MAC design for this DetF WSN is its performance as a cooperative spectrum sensing system.

More specifically, the contributions of this paper are three fold: 1) We propose a spatial reuse MAC protocol based on TDMA/OFDMA for exchanging sensing results that avoids primary conflicts and saves bandwidth resources. As design approaches, we consider a greedy algorithm as well as an adaptive simulated annealing (ASA) technique. 2) We analyze the degradation introduced by reporting channel errors on cooperative spectrum sensing performance with the k-out-of-n decision fusion rule. 3) For illustrative purposes we present numeri- cal results, in terms of Receiver Operating Characteristics (ROC) curves, that demonstrate the spectrum sensing performance of such DetF WSN with the spatial reuse MAC protocol in a grid network. However, the proposed spatial reuse MAC protocol is not limited to a grid network only, and can be employed in any network structure with an associated cooperating partner selection scheme. The rest of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 presents the system model and analyzes the performance of cooperative spectrum sensing using k-out-of-n decision fusion with imperfect reporting channels. The designs of the MAC protocol by using the greedy algorithm and the ASA technique are presented in Section 3. Numerical performance results for a grid network are presented in Section 4, and the conclusions are drawn in Section 5.

2. System Model and Preliminaries of Cooperative Spectrum Sensing

(A) Network architecture

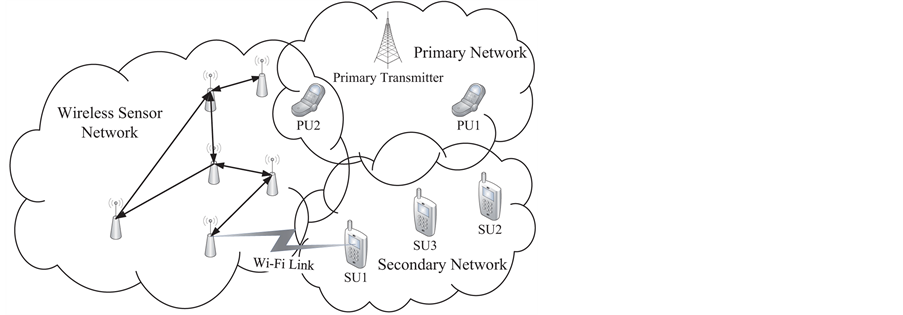

Consider a distributed DetF WSN illustrated in Figure 1, where the nods have spectrum sensing as well as communication capabilities. The operation of this WSN can be divided into two stages: 1) Intra-WSN Sensing and 2) WSN-SU Handshaking. The first stage is summarized as follows:

a) Measurement Phase: A sensor measures the received signal over the channel of interest.

b) Local Decision Phase: A sensor makes a hard decision based on its measurement via a local spectrum sensing scheme [16] .

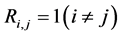

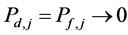

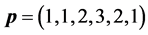

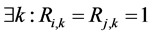

c) Communication Phase: Sensor exchange their local decisions through dedicated reporting channels. The cooperation between sensors is determined by a partner selection scheme specified by an adjacency matrix . When

. When  then this indicates that there is cooperation from the partner

then this indicates that there is cooperation from the partner  to recipient

to recipient . Otherwise,

. Otherwise, .

.

Figure 1. A WSN for cooperative spectrum sensing.

d) Final Decision Phase: A final decision is made by each sensor through combining the decisions gathered (including its own), according to a decision fusion rule.

e) The four phases above are repeated for another channel of interest.

In the second stage the sensing results are made available to SUs, which is a topic beyond the scope of this paper that focusses on spectrum sensing.

(B) Channel model

All wireless channels in the system, including the reporting as well as the detecting channels, are modeled as time-invariant small-scale fading including path loss and additive interference.

Path loss model

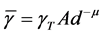

We use the simplified model of ( [17] , p. 47) to characterize the variation in the received signal power with distance:

(1)

(1)

where the path loss  is defined as the ratio of the transmit power

is defined as the ratio of the transmit power  over the received power

over the received power ,

,  is a constant which depends on the antenna cha- racteristics and the average channel attenuation,

is a constant which depends on the antenna cha- racteristics and the average channel attenuation,  is the distance between the transmitter and receiver, and

is the distance between the transmitter and receiver, and  is the path loss exponent.

is the path loss exponent.

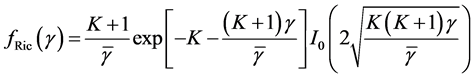

Small scale fading model

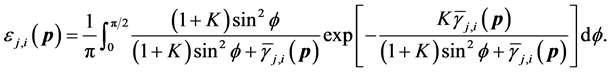

We assume small scale Rician fading for each communication link ( [18] , p. 23), with probability density function (PDF) of the instantaneous signal-to-noise ratio (SNR)  given by

given by

(2)

(2)

where ,

,  is the Rician fading parameter,

is the Rician fading parameter,  is the average received SNR, and

is the average received SNR, and

Interference model

We assume an additive interference model, in which a link treats all the other on-going transmissions on the same channel as noise [19] . Let

where

(C) Cooperative spectrum sensing through imperfect reporting channels

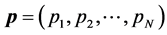

We assume that each sensor employs a local energy detector, and a channel to be sensed has center frequency

where

neous received SNR of primary signal at

where

where

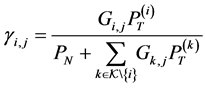

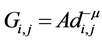

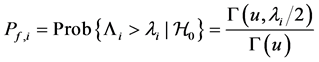

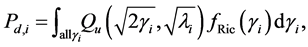

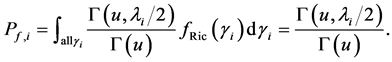

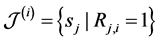

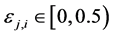

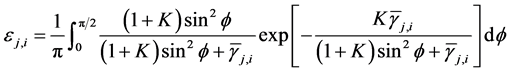

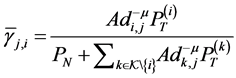

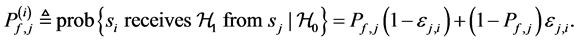

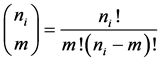

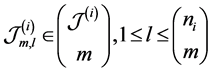

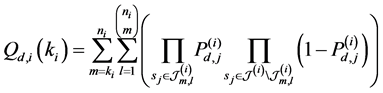

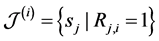

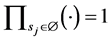

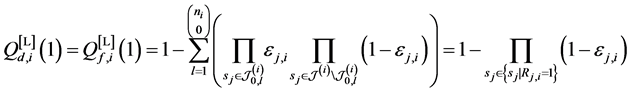

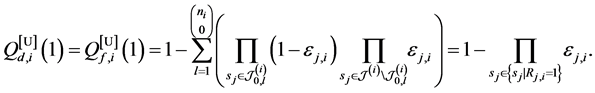

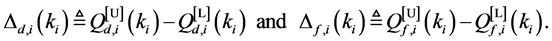

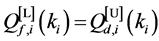

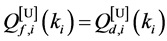

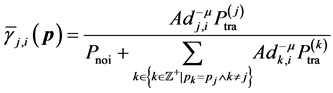

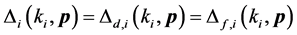

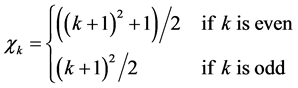

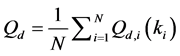

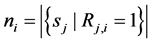

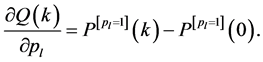

We assume that each sensing node gathers hard decisions from other partner nodes including its own decision, and uses the k-out-of-n fusion rule to produce a final decision ( [22] , pp. 59-61). We define the partner set of a sensor

where

The channel from

where

Hence from (3),

If an error occurs when

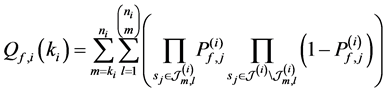

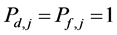

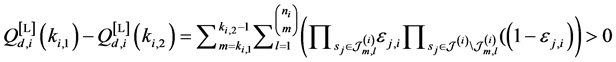

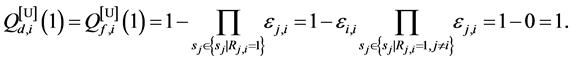

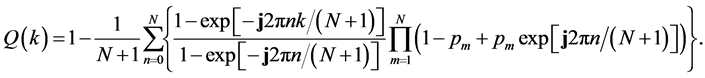

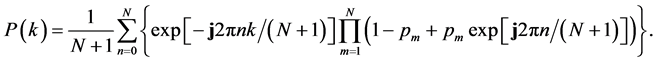

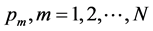

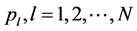

We assume that each sensor experiences i.i.d. Rician fading, and performs spectrum sensing independently. In this paper, we employ combinatorial nota-

tions as in [23] . We use

sents one m-combination of

where

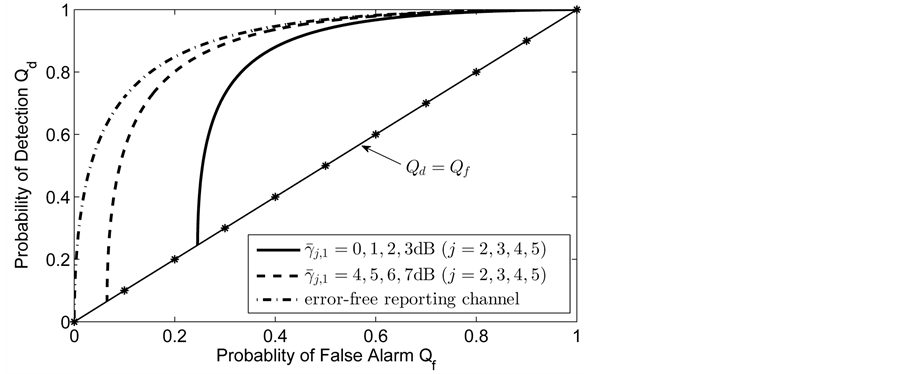

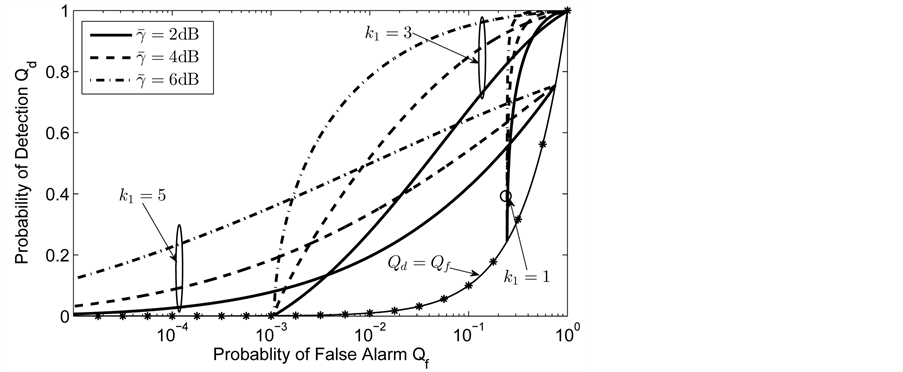

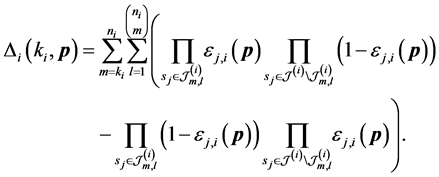

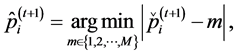

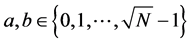

In Figure 2 we present the impacts of reporting channel errors on cooperative spectrum sensing performance by illustrating ROC curves of

Figure 2.

by reporting channel errors for OR rule (

-When

-When

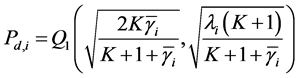

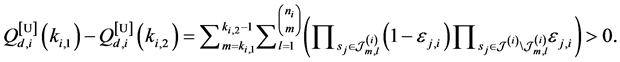

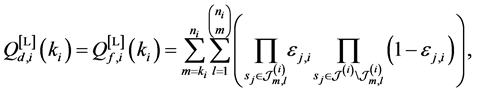

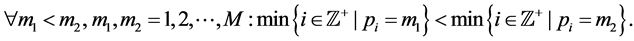

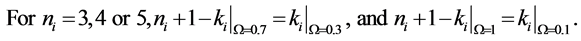

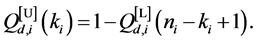

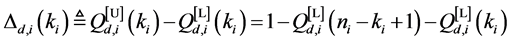

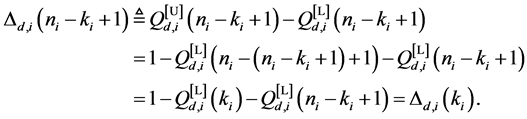

Property 1. For a partner set

Proof: Suppose that there are

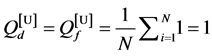

Therefore, using (11) and (12) with

The OR fusion rule is a special case when

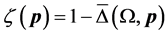

Define the Achievable Range of

From (13) and (14), we can see that

Property 2. For fixed

Follows directly from (13), (14) and (17).

Property 3. For fixed

For any

Property 4.

See Appendix B for proof.

(D) Other system setup assumptions

For network design purposes, we also make the following assumptions:

-Sensors are static after deployed.

-Each sensor employs an omni-directional antenna.

-A partner selection scheme has been devised to generate the adjacency matrix R for cooperation.

-Each sensor is in direct transmission range of its partners.

-The transmit power of each sensor is constant.

-Sensors communicate by broadcasting, and can dynamically switch to different sub-carriers.

-Sensors can transmit and receive at the same time on different sub-carriers.

-Sensors are synchronized ensuring time synchronous operation.

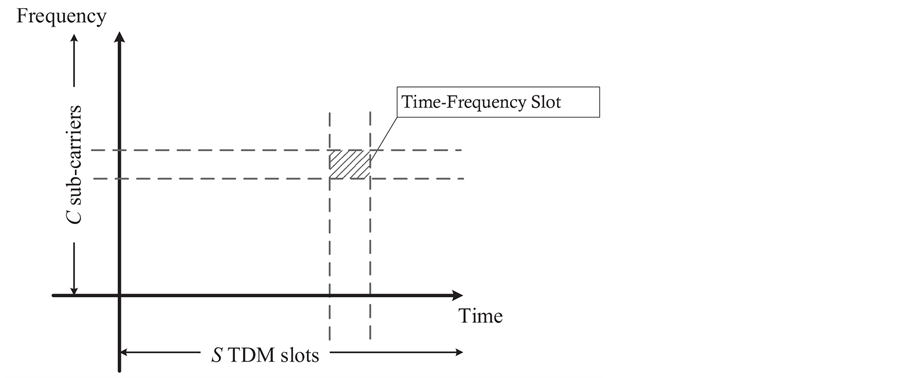

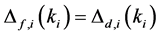

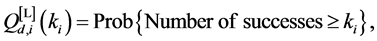

3. Spatial Reuse MAC Protocol Based on Hybrid TDMA/OFDMA

(A) MAC Design Concept

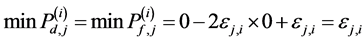

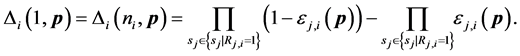

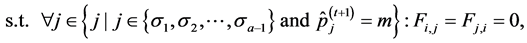

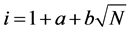

Our MAC protocol is based on TDMA/OFDMA, employing a frame of S time slots and C orthogonal sub-carriers as illustrated in Figure 3. An intuitive approach is to schedule each sensor into a particular time-frequency (T-F) slot [25] . Such a scheme is unrealistic since the number of required slots will increase linearly with the number of sensors. This problem can be solved by allowing a transmitter to share a slot with other far enough ones. The MAC protocol in

Figure 3. A MAC structure based on TDMA/OFDMA.

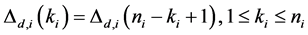

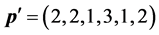

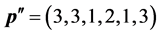

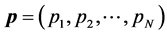

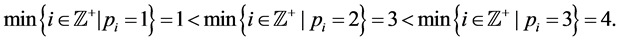

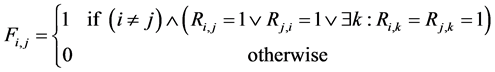

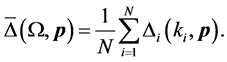

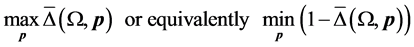

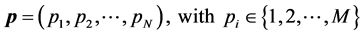

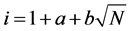

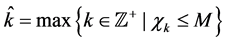

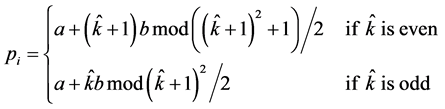

[26] reduces the number of required slots by dividing sensors into groups which can communicate simultaneously, employing spatial reuse for scheduling. The objective is to divide the N sensors into M separate sets, and assign one T-F slot to the sensors in the same set. The scheduling result is defined as an N-dimen- sional vector

We assume that the T-F slots have identical frame lengths as well as sub- carrier bandwidths. Thus, we only need to care about the T-F slot sharing relationship between sensors, rather than a sensor’s specific slot ID. For instance, if

where

When

where

In other cases, there exists a secondary conflict, which can be permitted if the impact caused by mutual interference is acceptable. Given that

where

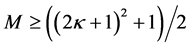

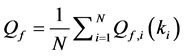

(B) Problem formulation

The distance matrix

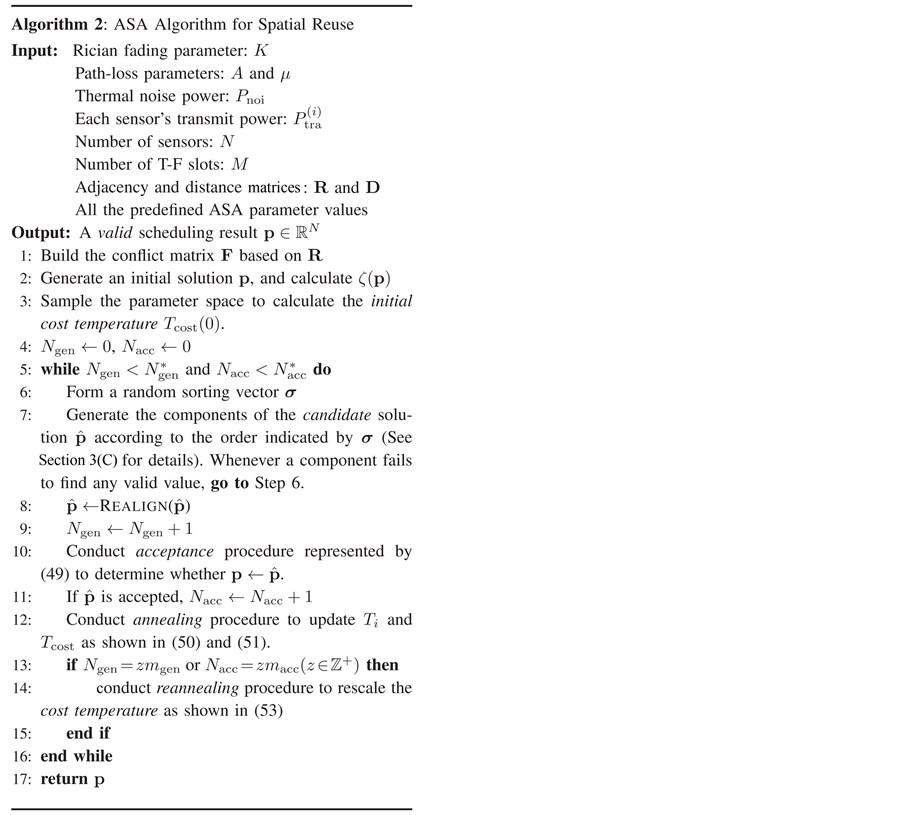

The adjacency matrix

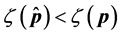

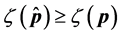

Given a certain number of slots M, our spatial reuse MAC protocol aims at providing a partition of the N sensors to avoid any primary conflict, and minimize the degradation caused by the BEPs on communication links between sensors. We focus on maximizing the Achievable Range of the probability of detection or false alarm,

The OR fusion rule (

The network fusion factor

Therefore, with the adjacency matrix

s.t.

where (26) is the scheduling result, (27) is the constraint for primary conflicts, and (28) is the constraint to avoid repetition. If

which is called the Network Achievable Range Loss of probability of detection or false alarm.

Essentially, such a MAC design is a combinatorial optimization problem, that is usually computationally intractable for practical applications [27] . Many combinatorial optimization problems of scheduling or channel assignment in wireless networks using similar models are too complicated for exact solution. In [28] [29] [30] [31] [32] , efforts have been invested in developing techniques based on heuristic combinatorial optimization for such problems [33] [34] . Common heuristic methods for solving such problems include: Tabu Search, Genetic Algorithms, Simulated Annealing, Ant System, Neural Networks, [33] . Next we consider two approaches: Greedy Algorithm and Simulated Annealing.

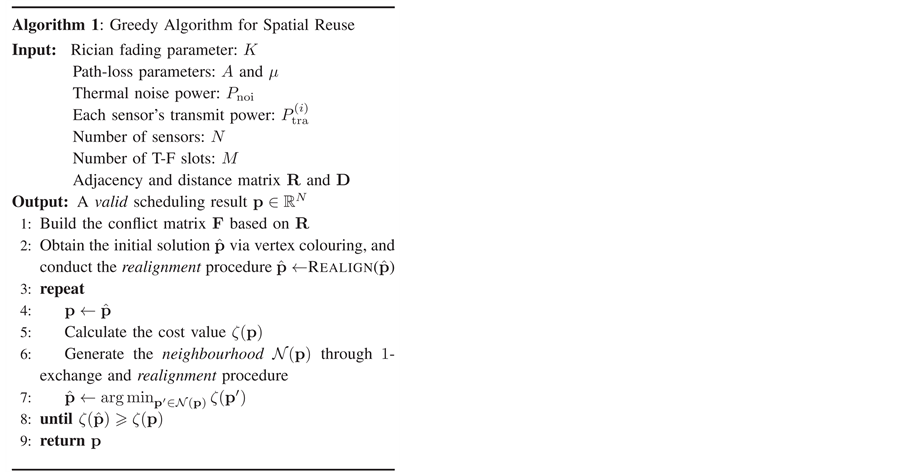

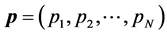

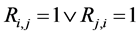

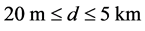

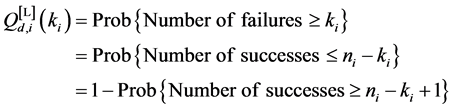

(C) Spatial reuse by graph colouring and greedy algorithm

We first form

i) The degree is the number of edges incident to a vertex.

ii) The saturation degree is the number of different colours in the neighbors of a vertex.

To start the DSatur algorithm we number the colours sequentially, and assign colour 1 to the vertex with the highest degree. In case of a tie, choose the one with the smallest sensor index. Select the next vertex with the highest saturation degree, and in case of a tie choose the vertex with the highest degree. Next, search the colours in ascending order, and find the first available one which hasn’t been assigned to any neighbour of the current vertex. Assign this colour to the current vertex, and keep checking the remaining uncoloured vertices in such an order until all the vertices are coloured. Let

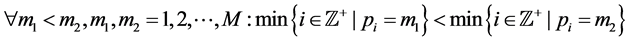

The initial generated solution may conflict with condition (28). So we perform the realignment procedure, which will be referred to as REALIGN(

a) Initialization:

b) Find the smallest index

c) For all the indices

d)

e) Repeat b) - d) until

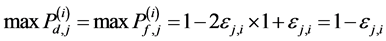

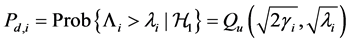

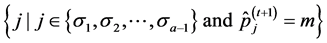

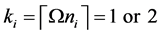

Next we present the complete Greedy Algorithm. Let

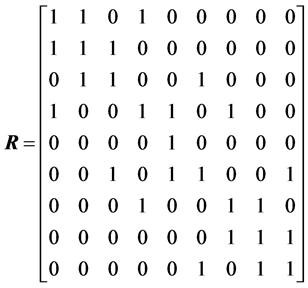

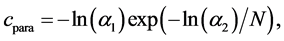

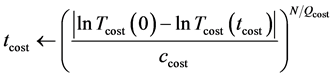

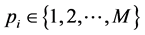

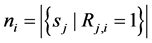

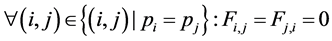

(D) Spatial reuse by adaptive simulated annealing

Despite its easy implementation and low complexity, the greedy algorithm cannot guarantee a globally optimal solution. Hence we propose an alternative approach using Adaptive Simulated Annealing (ASA) [38] . Simulated Annealing is a probabilistic method whose random search process mimics the physical annealing process [39] . It originates from the principles of thermodynamics associated with making a metal “freeze” into a crystalline structure at a mini- mum energy configuration, when cooled slowly from a state of high temperature. If its cooling process is well controlled, the algorithm can converge to a global optimum. The ASA algorithm permits an exponentially decreasing annealing schedule which greatly accelerates the optimization process compared with some traditional simulated annealing algorithms [40] . Moreover, the re-annealing procedure is introduced in ASA to adapt to changing sensitivities in the multi- dimensional parameter-space. More details on ASA are provided in Appendix C.

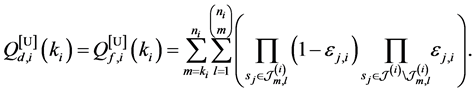

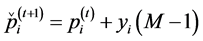

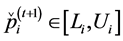

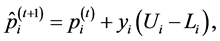

In our work, the components of

Figure 4. Greedy algorithm for spatial reuse.

where

into the mth slot before

In our work the acceptance and annealing procedures are the same as those described in Appendix C. However, we bypass the reannealing stage for temperature parameters, and only conduct this procedure on cost temperatures. This stage is optional, and since the components of

4. Performance Results for a Grid Network

(A) Scenario setup

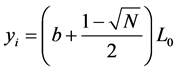

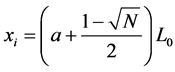

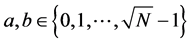

The sensors are assumed to be deployed on the grid of a target square region, with Euclidean distance between two nearest sensors fixed to

the coordinates of the sensors are

where

As to the partner selection scheme, the priority is given to the nearest sensors. We consider four adjacency matrix structures, and use the following cooperation levels to define them:

i) CL0: No cooperation between sensors, and thus

ii) CL2: A sensor selects itself and two other nearest sensors as its partners. If there are several sensors with the same distance, select in the ascending order of the sensor IDs.

iii) CL4: A sensor selects all the sensors within

iv) CL8: A sensor selects all the sensors within

Figure 5. ASA algorithm for spatial reuse.

We choose the COST-Walfish-Ikegami (COST-WI) model as the empirical path-loss model in the WSN, with parameters set for the Urban Macro scenario [41] . This model can be viewed as a simplified path-loss model in (1), with

The C-language implementation of the ASA algorithm is based on the source code provided by A. L. Ingber, which is available at

(B) Features of the grid network

We first build an undirected grid graph by considering all the sensors as

Table 1. Parameter settings for numerical results.

Table 2. Key parameters and options of ASA.

vertices, with an edge between any two sensors whose Euclidean distance is

-For CL2 and CL4, the grid distance between any partner-receiver pair is 1. If no two sensors within grid distance 2 share the same slot, no primary conflict exists in the WSN.

-For CL8, the longest grid distance between any partner-receiver pair is 2. If no two sensors within grid distance 4 share the same slot, no primary conflict exists in the WSN.

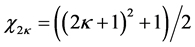

If the T-F slots are viewed as “colours”, then for CL2 and CL4, a 2-distance colouring of the grid graph is a feasible solution, and for CL8, a 4-distance colouring is a feasible solution. The k-distance colouring is defined as a vertex colouring such that no two vertices lying at the grid distance less than or equal to k are assigned the same colour. The minimum number of colours necessary for the k-distance colouring of a grid graph, denoted by

In summary, for the grid network with the partner selection scheme described above, if the longest grid distance between any partner--receiver pair is

In addition, for the grid network, we introduce an alternative method to generate the initial valid solution, which is based on a deterministic approach of k-distance colouring:

a) Find

b) Obtain an initial solution

where

c) Realignment procedure: p¬REALIGN(p)

The scheduling

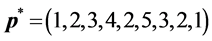

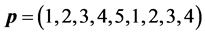

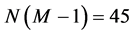

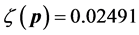

(C) Verification of the algorithms

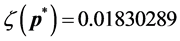

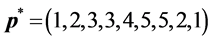

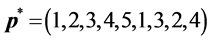

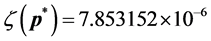

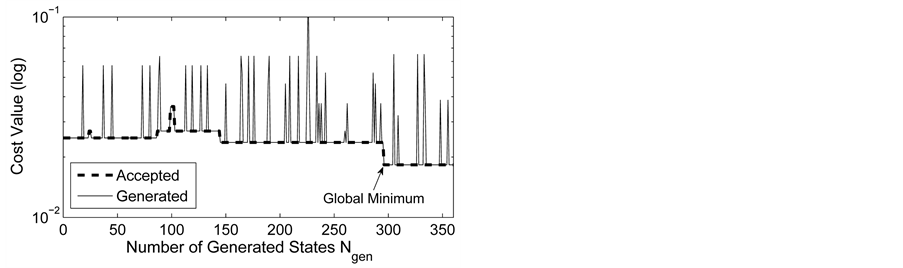

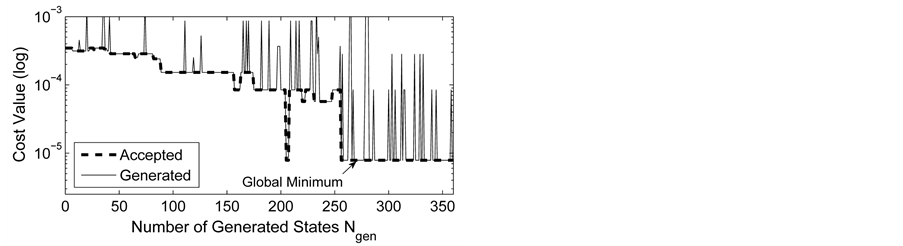

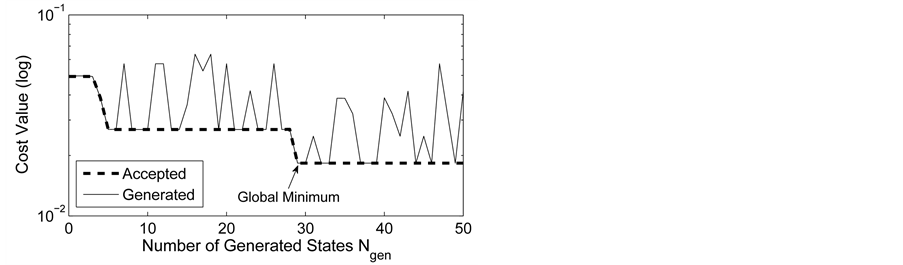

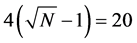

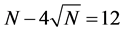

This example shows how the greedy algorithm may be trapped in local minima, and how the ASA algorithm can reach the global optimum. We consider a small network with 9 sensors as illustrated in Section 4(A), and set

The number of partners of each sensor is

-When

-When

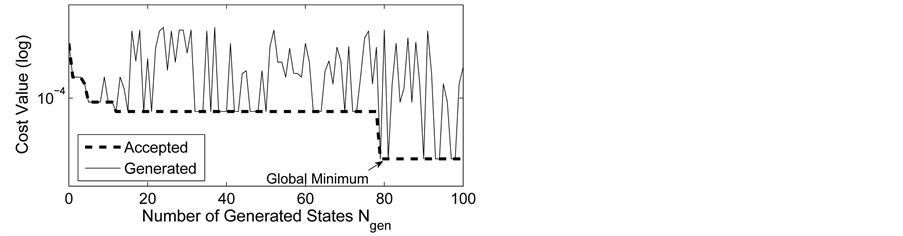

Next, we apply a relatively slow ASA algorithm with

Figure 6. The cost value (log) generated and accepted at each state of the relatively slow ASA algorithms for (a)

-When

-When

We also apply the normal generating procedure illustrated in Section 3(C) with realignment and the ASA parameters summarized in Table 2. The cost values generated and accepted at each state are shown in Figure 7, in the same form as Figure 6. If

(D) ROC curves for different configurations

We analyse the spectrum sensing performance of the grid WSN through ROC curves, which display

defined in (11) and (12). We use the fusion factor

Figure 7. The cost value (log) generated and accepted at each state of the normal ASA algorithms for (a)

Thus, the maximum value of

In each case, we change one network parameter while fixing others, and use both greedy and ASA algorithms to realize spatial reuse of T-F slots. The k- distance colouring scheme is used for initialization methods with both algorithms. After obtaining the output of the protocol,

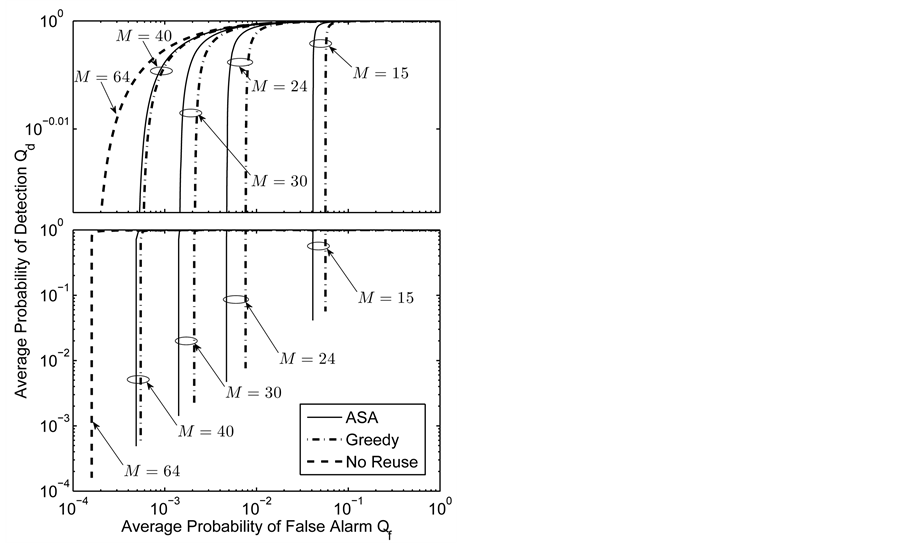

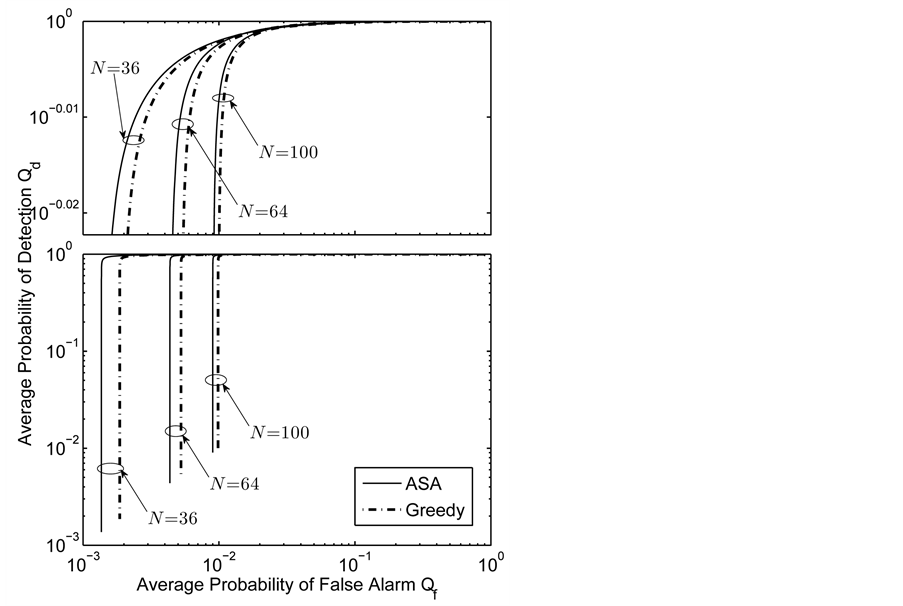

Different numbers of T-F slots

In Figure 8 we present the ROC curves for different values of M with

Figure 8. Average

sensing performance, that serves as a benchmark. At

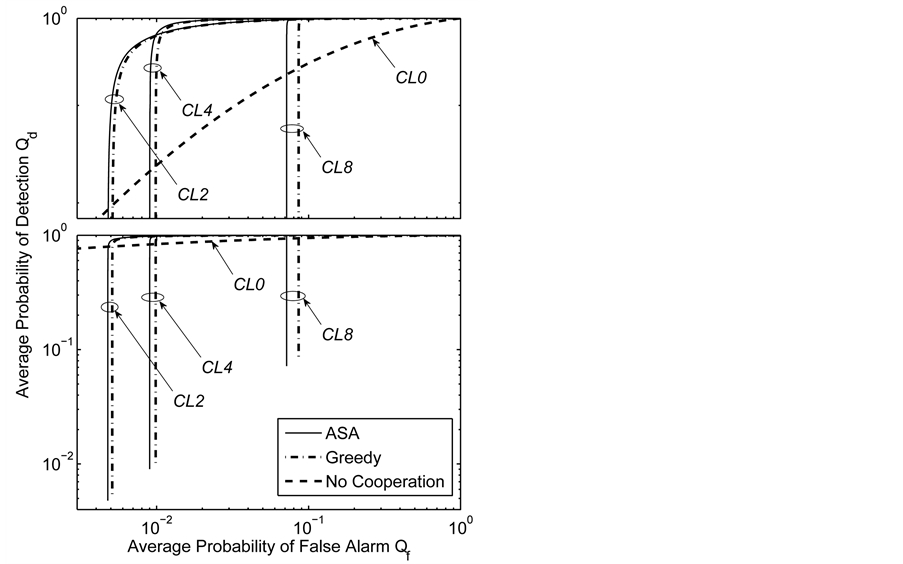

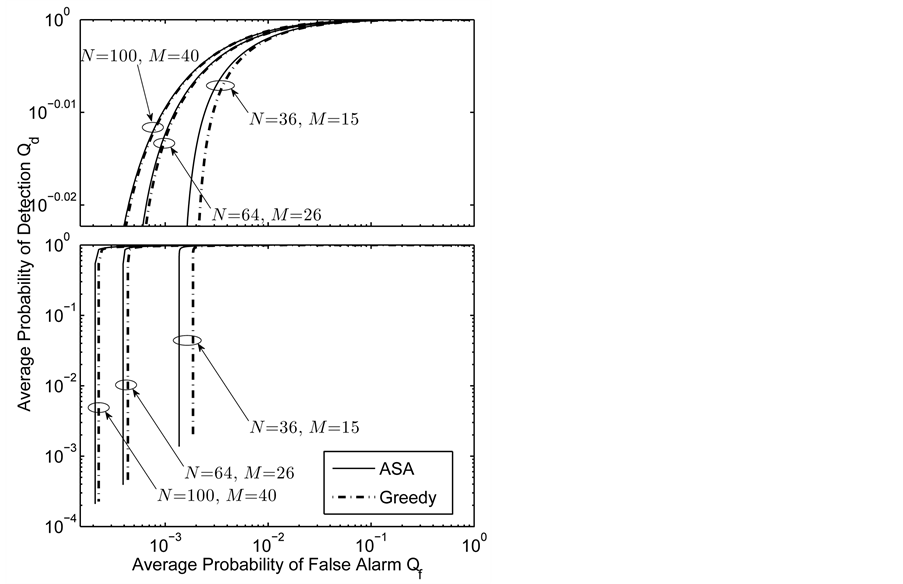

Different cooperation levels

We evaluate the performance with different cooperation levels (defined in Section 4(A) in Figure 9, where

Next, we focus on the curves of one algorithm at different cooperation levels. When the cooperation level increases, the existing partners for the lower cooperation level remain in the set

Figure 9. Average

Figure 9. When

Different network sizes

Three networks sizes,

For CL4, a sensor located at the corner has 3 partners, the one on the edge has 4 partners, while any other sensor has 5 partners. When N is increased, the proportion of sensors on the edge

Figure 10. Average

Figure 11. Average

sensors sharing the same slot. Thus, the network interference level increases, resulting in higher average BEP of communication links. As shown in Figure 10, for relatively high

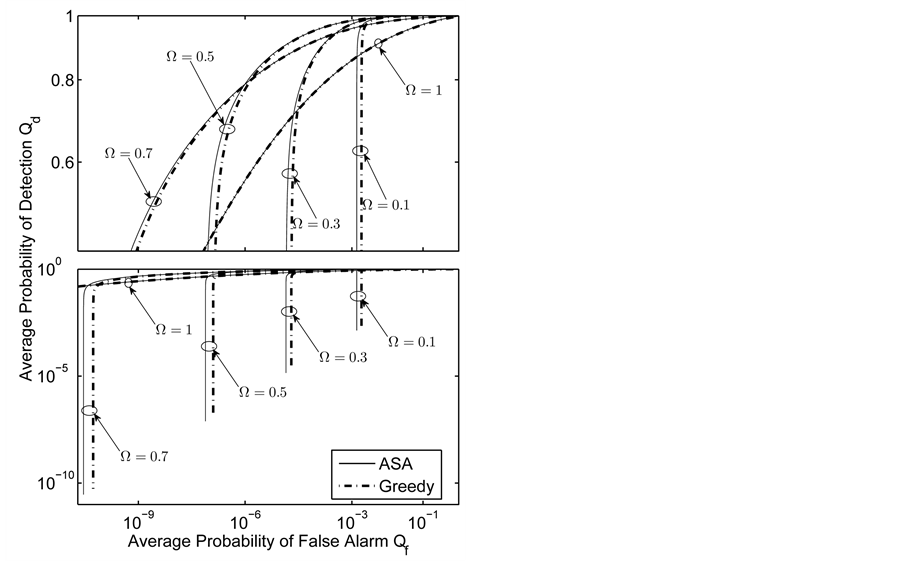

Different decision fusion rules

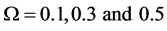

The ROC curves for fusion factor values

each sensor is

Thus, according to Property 4,

Figure 12. Average

so do

In Figure 12, we see that the separation between the ROC curves of the two algorithms becomes smaller as

5. Conclusions

In this paper, we analysed cooperative spectrum sensing performance using the k-out-of-n decision fusion rule with imperfect reporting channels, and derived the upper and lower bounds of probabilities of detection and false alarm. Then, we introduced a DetF distributed WSN for cooperative spectrum sensing, and proposed a spatial reuse MAC protocol based on TDMA/OFDMA. Two design approaches for the MAC protocol were considered: greedy and ASA algorithms. Finally, for a grid WSN, we discussed how to construct the adjacency matrix characterizing the cooperating relations between sensors. We also explain how to determine the minimum number of T-F slots, and get an initial valid solution via a k-distance colouring method.

Numerical results for a grid network in Section 4 show how the spectrum sensing performance is influenced by system parameters, and also present a comparison of the ASA and greedy algorithms. The ROC curves in Figures 8-11 show that using the OR decision fusion rule, the difference between the curves of the two algorithms is very small in relatively high

When comparing the ROC curves of one algorithm with different network settings, we can see the influence of system parameters. From Figure 8 we see that our spatial reuse MAC protocol can save T-F slots without significant impact on the sensing performance at certain

Cite this paper

Shao, X. and Leib, H. (2017) Media Access with Spatial Reuse for Cooperative Spectrum Sensing. Wireless Sensor Network, 9, 205-237. https://doi.org/10.4236/wsn.2017.97012

References

- 1. Letaief, K. and Zhang, W. (2009) Cooperative Communications for Cognitive Radio Networks. Proceedings of the IEEE, 97, 878-893. https://doi.org/10.1109/JPROC.2009.2015716

- 2. Akyildiz, I.F., Lee, W.-Y., Vuran, M.C. and Mohanty, S. (2006) NeXt Generation/Dynamic Spectrum Access/Cognitive Radio Wireless Networks: A Survey. Computer Networks, 50, 2127-2159. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comnet.2006.05.001

- 3. Stevenson, C.R., et al. (2009) IEEE 802.22: The First Cognitive Radio Wireless Regional Area Network Standard. IEEE Communications Magazine, 47, 130-138. https://doi.org/10.1109/MCOM.2009.4752688

- 4. Abinader, F., Almeida, E.P., Chaves, F.S., Cavalcante, A.M., Vieira, R.D., Paiva, R.C., Sobrinho, A.M., Choudhury, S., Tuomaala, E., Doppler K., et al. (2014) Enabling the Coexistence of LTE and Wi-Fi in Unlicensed Bands. Communications Magazine, IEEE, 52, 54-61. https://doi.org/10.1109/MCOM.2014.6957143

- 5. Zhang, H., Chu, X., Guo, W. and Wang, S. (2015) Coexistence of Wi-Fi and Heterogeneous Small Cell Networks Sharing Unlicensed Spectrum. Communications Magazine, IEEE, 53, 158-164. https://doi.org/10.1109/MCOM.2015.7060498

- 6. Tandra, R. and Sahai, A. (2008) SNR Walls for Signal Detection. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Signal Processing, 2, 4-17. https://doi.org/10.1109/JSTSP.2007.914879

- 7. Duan, D., Yang, L. and Principe, J.C. (2010) Cooperative Diversity of Spectrum Sensing for Cognitive Radio Systems. IEEE Transactions on Signal Processing, 58, 3218-3227. https://doi.org/10.1109/TSP.2010.2044612

- 8. Atapattu, S., Tellambura, C. and Jiang, H. (2011) Energy Detection Based Cooperative Spectrum Sensing in Cognitive Radio Networks. IEEE Transactions on Wireless Communications, 10, 1232-1241. https://doi.org/10.1109/TWC.2011.012411.100611

- 9. Mishra, S.M., Sahai, A. and Brodersen, R. (2006) Cooperative Sensing among Cognitive Radios. 2006 IEEE International Conference on Communications, Istanbul, 11-15 June 2006, 1658-1664. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICC.2006.254957

- 10. Han, Z., Fan, R. and Jiang, H. (2009) Replacement of Spectrum Sensing in Cognitive Radio. IEEE Transactions on Wireless Communications, 8, 2819-2826. https://doi.org/10.1109/TWC.2009.080603

- 11. Shankar, S.N., Cordeiro, C. and Challapali, K. (2005) Spectrum Agile Radios: Utilization and Sensing Architectures. First IEEE International Symposium on New Frontiers in Dynamic Spectrum Access Networks,Baltimore, 8-11 November 2005, 160-169.

- 12. Sahai, A., Mishra, S.M., Tandra, R. and Hoven, N. (2006) Sensing for Communication: The Case of Cognitive Radio. Allerton Conference on Communication, Control, and Computing, Allerton Park, Monticello, 27-29 September 2006, 1035-1037.

- 13. Akyildiz, I.F., Lo, B.F. and Balakrishnan, R. (2011) Cooperative Spectrum Sensing in Cognitive Radio Networks: A Survey. Physical Communication, 4, 40-62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phycom.2010.12.003

- 14. Bachir, A., Dohler, M., Watteyne, T. and Leung, K.K. (2010) MAC Essentials for Wireless Sensor Networks. IEEE Communications Surveys and Tutorials, 12, 222- 248. https://doi.org/10.1109/SURV.2010.020510.00058

- 15. Demirkol, I., Ersoy, C. and Alagoz, F. (2006) MAC Protocols for Wireless Sensor Networks: A Survey. IEEE Communications Magazine, 6, 115-121. https://doi.org/10.1109/MCOM.2006.1632658

- 16. Chaudhari, S., Lunden, J., Koivunen, V. and Poor, H.V. (2012) Cooperative sensing with Imperfect Reporting Channels: Hard Decisions or Soft Decisions? IEEE Transactions on Signal Processing, 60, 18-28. https://doi.org/10.1109/TSP.2011.2170978

- 17. Goldsmith, A. (2005) Wireless Communications. Cambridge University Press, New York. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511841224

- 18. Simon, M.K. and Alouini, M.-S. (2005) Digital Communication over Fading Channels. John Wiley & Sons, Hoboken.

- 19. Iyer, A., Rosenberg, C. and Karnik, A. (2009) What Is the Right Model for Wireless Channel Interference. IEEE Transactions on Wireless Communications, 8, 2662- 2671. https://doi.org/10.1109/twc.2009.080720

- 20. Ghasemi, A. and Sousa, E.S. (2005) Collaborative Spectrum Sensing for Opportunistic Access in Fading Environments. First IEEE International Symposium on New Frontiers in Dynamic Spectrum Access Networks, Baltimore, 8-11 November 2005, 131-136.

- 21. Digham, F.F., Alouini, M.-S. and Simon, M.K. (2003) On the Energy Detection of Unknown Signals over Fading Channels. IEEE International Conference on Communications,, 5, 3575-3579. https://doi.org/10.1109/icc.2003.1204119

- 22. Varshney, P.K. (1997) Distributed Detection and Data Fusion. In: Burrus, C., Ed., Springer, New York. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4612-1904-0

- 23. Hong, Y. (2013) On Computing the Distribution Function for the Poisson Binomial Distribution. Computational Statistics and Data Analysis, 59, 41-51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csda.2012.10.006

- 24. Fernandez, M. and Williams, S. (2010) Closed-Form Expression for the Poisson-Binomial Probability Density Function. Aerospace and Electronic Systems, IEEE Transactions on, 46, 803-817. https://doi.org/10.1109/TAES.2010.5461658

- 25. Cidon, I. and Sidi, M. (1989) Distributed Assignment Algorithm for Multihop Packet Radio Networks. IEEE Transactions on Computers, 38, 1353-1361. https://doi.org/10.1109/12.35830

- 26. Sagduyu, Y. and Ephremides, A. (2004) The Problem of Medium Access Control in Wireless Sensor Networks. IEEE Wireless Communications, 11, 44-53. https://doi.org/10.1109/MWC.2004.1368896

- 27. Ausiello, G., Crescenzi, P., Gambosi, G., Kann, V., Marchetti-Spaccamela, A. and Protasi, M. (2012) Complexity and Approximation: Combinatorial Optimization Problems and Their Approximability Properties. Springer Science & Business Media, Berlin.

- 28. Maniezzo, V. and Carbonaro, A. (2000) An Ants Heuristic for the Frequency Assignment Problem. Future Generation Computer Systems, 16, 927-935. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0167-739X(00)00046-7

- 29. Krumke, S.O., Marathe, M.V. and Ravi, S. (2001) Models and Approximation Algorithms for Channel Assignment in Radio Networks. Wireless Networks, 7, 575-584. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1012311216333

- 30. ElBatt, T. and Ephremides, A. (2004) Joint Scheduling and Power Control for Wireless Ad Hoc Networks. IEEE Transactions on Wireless Communications, 3, 74-85. https://doi.org/10.1109/TWC.2003.819032

- 31. Alicherry, M., Bhatia, R., and Li, L.E. (2005) Joint Channel Assignment and Routing for Throughput Optimization in Multi-Radio Wireless Mesh Networks. Proceedings of the 11th Annual International Conference on Mobile Computing and Networking, 28 August-2 September, 2005, 58-72. https://doi.org/10.1145/1080829.1080836

- 32. Subramanian, A.P., Gupta, H., Das, S.R. and Cao, J. (2008) Minimum interference Channel Assignment in Multiradio Wireless Mesh Networks. Mobile Computing, IEEE Transactions on, 7, 1459-1473. https://doi.org/10.1109/TMC.2008.70

- 33. Papadimitriou, C.H. and Steiglitz, K. (1998) Combinatorial Optimization: Algorithms and Complexity. Courier Corporation, North Chelmsford.

- 34. Blum, C. and Roli, A. (2003) Metaheuristics in Combinatorial Optimization: Overview and Conceptual Comparison. ACM Computing Surveys (CSUR), 35, 268-308. https://doi.org/10.1145/937503.937505

- 35. Brelaz, D. (1979) New Methods to Color the Vertices of a Graph. Communications of the ACM, 22, 251-256. https://doi.org/10.1145/359094.359101

- 36. Chaitin, G.J., Auslander, M.A., Chandra, A.K., Cocke, J., Hopkins, M.E. and Markstein, P.W. (1981) Register Allocation via Coloring. Computer Languages, 6, 47-57. https://doi.org/10.1016/0096-0551(81)90048-5

- 37. Avanthay, C., Hertz, A. and Zufferey, N. (2003) A Variable Neighborhood Search for Graph Coloring. European Journal of Operational Research, 151, 379-388. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0377-2217(02)00832-9

- 38. Ingber, L., Petraglia, A., Petraglia, M.R., Machado, M.A.S., et al. (2012) Adaptive Simulated Annealing. Stochastic Global Optimization and Its Applications with Fuzzy Adaptive Simulated Annealing. Springer, New York, 33-62.

- 39. Bertsimas, D., Tsitsiklis, J., et al. (1993) Simulated Annealing. Statistical Science, 8, 10-15. https://doi.org/10.1214/ss/1177011077

- 40. Szu, H. and Hartley, R. (1987) Fast Simulated Annealing. Physics Letters A, 122, 157-162. https://doi.org/10.1016/0375-9601(87)90796-1

- 41. Baum, D.S., Hansen, J. and Salo, J. (2005) An Interim Channel Model for Beyond- 3G Systems: Extending the 3GPP Spatial Channel Model (SCM). Vehicular Technology Conference (spring), 5, 3132-3136. https://doi.org/10.1109/vetecs.2005.1543924

- 42. Unnikrishnan, J. and Veeravalli, V.V. (2008) Cooperative Sensing for Primary Detection in Cognitive Radio. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Signal Processing, 2, 18-27. https://doi.org/10.1109/JSTSP.2007.914880

- 43. Fertin, G., Godard, E. and Raspaud, A. (2003) Acyclic and K-Distance Coloring of the Grid. Information Processing Letters, 87, 51-58. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0020-0190(03)00232-1

- 44. Kuo, W. and Zuo, M.J. (2003) Optimal reliability Modeling: Principles and Applications, John Wiley & Sons, Hoboken.

Appendix A

Consider N independent Bernoulli trials, where for the mth trial

In addition, the Poisson-Binomial probability mass function (PMF) is ( [24] , Equation (5)),

Lemma 1. For a certain series of

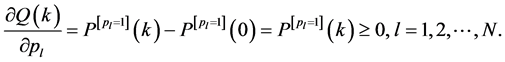

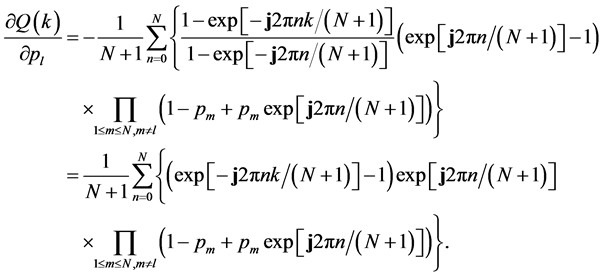

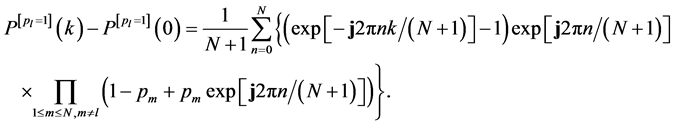

Proof: We obtain the partial derivative of

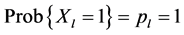

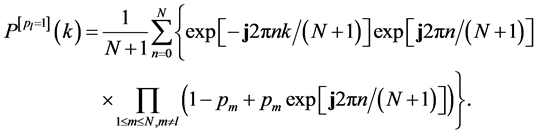

Then we consider a certain series of N Bernoulli trials where

When

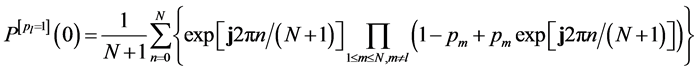

Based on (39) and (40), we get

The right-hand side of (41) is exactly the same as that of (38), and hence

When

Appendix B

Proof of Property 4

Suppose that there are

and

where (44) is also given in ( [44] , pp. 251-253). Hence from (43) and (44)

Then, based on (45) and the definition of

and

Appendix C

Details of ASA

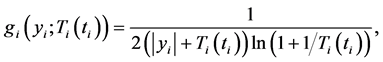

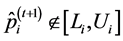

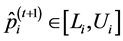

The ASA algorithm consists of three major stages: generating, acceptance, and annealing [38] . In a N-dimensional parameter space with the ith parameter having the range

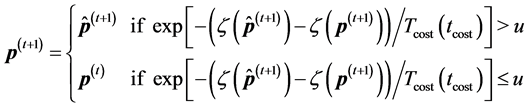

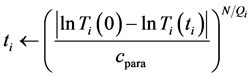

The acceptance procedure determines whether the candidate point

where

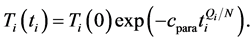

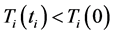

The annealing procedure for the parameter temperature

The initial parameter temperature

where

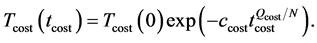

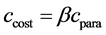

The annealing procedure for the cost temperature

The ASA algorithm first generates

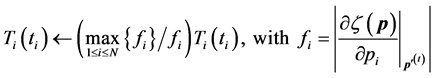

An optional reannealing procedure will periodically rescale

where

When

Thus, according to (51),

Submit or recommend next manuscript to SCIRP and we will provide best service for you:

Accepting pre-submission inquiries through Email, Facebook, LinkedIn, Twitter, etc.

A wide selection of journals (inclusive of 9 subjects, more than 200 journals)

Providing 24-hour high-quality service

User-friendly online submission system

Fair and swift peer-review system

Efficient typesetting and proofreading procedure

Display of the result of downloads and visits, as well as the number of cited articles

Maximum dissemination of your research work

Submit your manuscript at: http://papersubmission.scirp.org/

Or contact wsn@scirp.org