Health

Vol. 4 No. 2 (2012) , Article ID: 17472 , 7 pages DOI:10.4236/health.2012.42008

Health 3.0—The patient-clinician “arabic spring” in healthcare

![]()

Research and Intervention Centre for Healthy Workplaces (CRISO), McGill University Health Centre, Montréal, Canada; *Corresponding Author: serge.gagnon@criso.ca

Received 18 November 2011; revised 28 December 2011; accepted 9 January 2012

Keywords: Dependency and Co-Responsibility Paradigm; Communication and Self-Managed Health Technologies; Chronic Diseases; Runaway Utilization of Health Services; Development Matrix of Health 3.0 Governance; MD 3.0 Relational Model; Citizen-Patient 3.0 Behavioral Profile

ABSTRACT

A growing number of citizen-patients and clinicians use Communication and Self-Managed Health Technologies (CSMHT) in their relationship. Doing so, they shift from the current paradigm of dependency to a co-responsibility paradigm in healthcare. Facing the runaway utilization of health services, we need to think “outside the box” to unblock the system. A Health 3.0 development model of governance that position patients as primary members of the clinicians’ team is presented to map this institutional transformation. At the practical level, an MD 3.0 relational model and a Citizen-Patient 3.0 behavioral profile are presented.

1. INTRODUCTION

The chronic problem of overflowing emergency rooms and hospitals are regularly making the news for the same enduring reasons: shortages, deficits in primary care and intermediate resource networks for long-term services, organizational performance issues, etc. While the authorities of public health networks are still looking “inside the box” and making big investments in top-down electronic tools (e.g. electronic medical records), a paradigmatic revolution is taking place. The traditional patient-clinician relationship is an endangered species. The Arabic Spring in healthcare is at the door!

Patients now have access to online social network sites and are able to see how other people in similar health situations have taken decisions about their own treatments and how they have managed their illness. Patients may now request second opinions by secured mail and verify hospital and doctor’s evaluations online. This is Health 2.0. In the near future, with the support of Web 3.0 technology, patients will be able to receive their genetic profile, configure semantic agents to monitor the evolution of new treatments for health problems for which they are at risk and create micro-communities of people who share similar risk profiles. Health messages corresponding to their specific risk profile will be sent to portable electronic devices, which will measure blood pressure, blood sugar and other vital signs. With these new peer-to-peer support communities and with secured technologies made available in a context of flexible MD relational approaches, they will be empowered to adopt many new responsibilities regarding their health and health treatments. This is Health 3.0.

2. HEALTH 2.0 IN USA

The “Health 2.0” movement was born in the UnitedStates in the late 1990s as consumers began to use the Internet to publish information on their own health experiences and to connect with one other. Since the fall of 2007, the group “Health 2.0 Advisors” has organized dozens of international conferences in USA, Japan and Europe. They have summed up the history of this movement in “The past and the future of Health 2.0” report [1].

According to this report, between 2005 and 2007, the Health 2.0 movement made considerable progress due to the emergence of three concomitant phenomena, linked to Web 2.0, which supports and promotes citizens’ autonomy when they are looking to manage their own health problems. These are 1) the development and increase of “online research” sites (specific answers to specific questions); 2) the explosion of online social networks (information sharing between members of various online communities, concerning different types of health topics) and 3) the increase of available self-managed health tools online and elsewhere on the market (availability of various assessment and compilation instruments as well as tools that can assist the user in interpreting his own health data, in decision-making and in care providing).

3. RUNAWAY UTILIZATION OF HEALTH SERVICES

The multiplication of chronic diseases within our aging population occurs in a social context that can be characterized by three major trends producing a “dependency circle” in health services: 1) “denial of mortality” leading people to consume, at any cost, any product or service that promises “lasting youth and beauty”; 2) marketers of health technologies feeding this denial of mortality by exaggerating the effectiveness of questionable anti-aging remedies; and 3) politicians depending on the two former groups (population and industries) to remain in Office! This dependency paradigm is therefore well rooted in our cultural, economic and political institutions. “Inside this box”, Health 3.0 appears as a disruptive innovation that will generate resistance. At the same time, since the beginning of the millennium, many authors [2] have emphasized that what was once the force of this old paradigm in healthcare, is now becoming its weakness.

As was well demonstrated by Kuhn, all paradigms contain the seeds of their own malediction: More it is ancient, more the reservoir of progress it could allow is consumed, more the contradictions linked to the concealment of natural complexity will be shocking and less it will be blamed because it will have formatted the spirits and chosen the elites of the moment among its best “puzzle makers”, the most skilled at assembling authorized puzzles and at ignoring the facetious reality that contradicts it. When this malediction reaches aversion, which gives rise to a breach of paradigm, the new model generally integrates the previous acquisitions within a vaster perspective, in the same way that a bi-dimensional model would be resolved into three dimensions. But for this virtuous movement to take place, the voices of those who think it’s time to think differently, must resonate loudly enough to weaken those who occupy decision-making positions, the “puzzle-makers” [3].

Many citizen-patients and clinicians have started to think differently regarding the dependency paradigm and have begun to invent solutions “outside the box” using Communication and Self-Managed Health Technologies (CSMHT) to push the health system toward a tri-dimensional way of making decisions about their health and health treatments (patients and doctors and CSMHT). For the first time in the history of humanity, the citizenpatients, in a greater number than can be imagined, can take charge of significant medical responsibilities. The “dependent patient” can be assisted to become the “primary member of the medical team” [4].

By replicating the current paradigm of dependency, the public network of health and social services denies itself of substantial and accessible resources, which would allow better management of the growing use of health services.

4. HEALTH 3.0 GOVERNANCE MODEL

Health 3.0 is a philosophy of management and a set of organization and delivery mechanisms of care and services that promotes new patient-clinicians relationships, assisted by CSMHT to foster patients’ autonomy, especially patients with chronic diseases. More precisely, it is:

• A new philosophy of management of health organizations leading to major changes in professional practices with patient-users as to promote and support autonomy, cooperation and co-responsibility;

• A set of organization and delivery mechanisms of care and services redefining and optimizing the respective contributions of caregivers and caretakers in a context where patients see their role being profoundly enhanced by the establishment of partnership relations with MDs and other health professionals, with the support of certified CSMHT.

The paradigm shift could occur in two stages. The current stage can be seen as a collective reaction to the dependency paradigm. It is characterized by the desire of citizen-patients to become more independent of institutions, with the support of technology. The Health 2.0 movement in the USA is an illustration of that stage. The next stage could be a phase of “institutionalization” of Health 2.0 practices and would suppose that healthcare institutions engage themselves in structural, cultural and professional transformations in line with the definition of Health 3.0 proposed above. Therefore Health 3.0 organizations would integrate, improve and ensure security of CSMHT in conformity with the five principles of the Canada Health Act.

The implementation of the Health 3.0 model of governance, based on greater autonomy and responsibility of the citizen-patients dealing with chronic diseases in respect to their health, care and treatments, and also based on a more authentic and egalitarian cooperation between health professionals and their clients, could significantly contribute to unblock the public health system, especially with persons suffering of one or many of the eight major chronic diseases listed by the Statistical Institute of Quebec: food and non-food allergies, arthritis or rheumatism, cancer, diabetes, hypertension, heart disease, obstructive pulmonary disease and thyroid problems [5]. According to Roy et al. (2010) [6], 55% of the total costs of public healthcare networks are linked to “chronic diseases with normal functioning” and “significant but stable incapacity including mental health problems”. The main goal of the services for those populations consists of supporting and empowering people to better cope with the disease or the incapacity. In many of those cases, patients and clinicians and CSMHT can be of help to reach that objective quickly, economically and even with a higher level of satisfaction for both the patients and the clinicians.

5. COLLECTIVELY FACING THE RUNAWAY UTILIZATION OF HEALTH SERVICES

Performance is now on the agenda of all healthcare organizations. Why not include citizen-patients in this search of increased performance by helping them become more independent and co-responsible of their health and health treatments thanks to empowering relationship with their clinicians and a better and more frequent use of available and certified CSMHT? How could public health organizations evolve in order to effectively promote the users’ potential contribution to the system’s performance?

As the aforementioned reference to Kuhn’s work on paradigms clearly describes, there comes a time when the potential for evolution and progress becomes marginal within old ways of thinking and doing, and significant gains are found 180 degrees from current positions. In other words, the return on investments gained in the current system will only reach a small fraction of those that could be realized in a new system of thinking and doing, the potential of the present system already being overtaxed and its leveraging capacity much reduced.

The patients and clinicians and CSMHT approaches are key levers to transform and improve tomorrow’s health system. However tools will not lead the transformation instead of people. Healthcare organizations are “people driven” systems. Even though more and more tools and technologies have the potential to transform the medical profession, the transformation will occur only if there is a paradigmatic shift in the caregiver/caretaker relationship model. The case of the Family Clinic of Cité de la Santé de Laval (Québec, Canada) with its CSMHT called DaVinci, is an innovative illustration of this transformational effort, lead by Dr. Marie-Therese Lussier and her team. According to their experience, the CSMHT can radically change and improve the way clinicians work together, the way teams of clinicians work with patients and the way patients “work” with their clinicians [7].

Obviously, technology cannot supersede the quality of human relations that must undeniably accompany the treatment and care of many patients. The CSMHT are not a panacea to the scarcity of resources but, as experienced in many others industries (e.g. travel, banking, real estate, shopping, etc.), they represent a promising mean to “unload” the public health network by designating citizenpatients 3.0 (see Table 1) as central actors of the system.

As an example, during the “3rd Annual Conference of the McGill University Health Centre’s Institute for Strategic Analysis and Innovation”, October 20th and 21st 2010, a large consensus was obtained between the participants to the effect that our health system is not very open to and barely impacted by the CSMHT. The main question was: “Would you agree that the next billion dollars in health and social services be spent on CSMHT?”. Seventy percent (70%) of participants answered “yes” to the question! In fact, 23 experts shared different point of views that can be classified into two groups: Those who emphasized the necessity to improve the current system with technologies (how we build electronic medical records, coordination between caregivers, security of privacy, etc.) —in short to do more of the same but more efficiently with technologies—and those who directly or indirectly highlighted that a real transformation will primarily depend on a reinvention of the clinicians-patients-CSMHT relationship in this system or other.

The question is not “Will the patient play a role in the management of his health and medical care in the future?” but rather: “How will he do it in partnership with his clinicians and with the support of certified CSMHT?”

6. HEALTH 3.0 DEVELOPMENT MATRIX

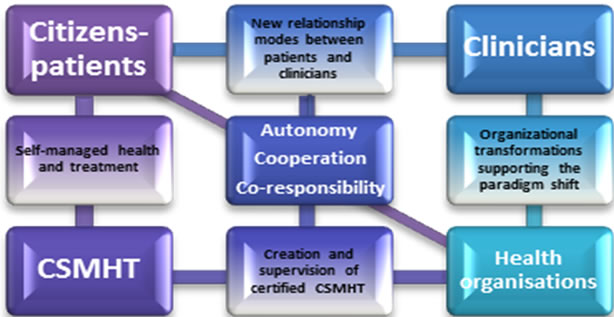

Figure 1 presents our exploratory model that maps four types of key interactions in this paradigmatic transformation: 1) healthcare organizations and caregivers; 2) caregivers and citizen-patients; 3) citizen-patients and CSMHT; 4) healthcare organizations and CSMHT. This model is based on the conviction that the sustainability of the public health network is tributary of a paradigm shift that will promote and support citizen-patients autonomy, coresponsibility and cooperation with clinicians.

Many questions can be raised with this model. In this paper, we address two questions related to the top axe of the model: the relationship between MDs/caregivers and citizen-patients. More precisely, what are the relational models adopted by MDs 3.0 and what is the behavioral profile of the citizen-patients 3.0?

7. MDS 3.0 RELATIONAL MODELS

We argue that more and more patients want to and are able to play a significant role in their diagnosis and treatments [8-11]. But delegation of responsibilities to the patient should be accompanied by information, training and coaching, as well as a real commitment of the patient in his learning process, which is a big challenge in many cases. The availability of CSMHT reinforces and even increases the patient’s ability to adopt these new responsibilities in the care plan. Many if not all leading universities in Quebec are currently researching in that direction [12] and Info Way Canada has called for Canadians’ innovative ideas on this subject, using a bottom-up approach 13].

At the same time, and with the best intentions, physicians frequently adopt a traditional, paterna-listic and unidirectional approach of authority with their patients and other health professionals [14]. Several factors encourage a revision of this traditional position: the level of education

Figure 1. The Health 3.0 development matrix.

of a large number of citizen-patients, an increase in egalitarian and democratic values, medical skill levels constantly increasing among non-physician caregivers such as nurse practitioners, an increase of patients with chronic diseases becoming “semi-experts” of their case, the experience of empowering relationships with other professionals, the discomfort of a growing number of physicians in the paternalistic model and, of course, the empowerment of patients stimulated by the CSMHT [15,16].

Many health experts around the world including doctors have begun to examine the issue [17]. In Montreal, Lussier and Richard (2008) [18] conducted a large literature review and examined relational models of authority, some of which have long been recognized in the leadership and management literature. On this basis, they produced a conceptual framework classifying different types of doctorpatient relationships that opens very interesting perspectives about the Health 3.0 model.

Figure 2 is a replication of their conceptual framework highlighting the fact that doctors and patients may find themselves in different situations and therefore, the relational model adopted by the physician should differ according to various care situations. This graph shows that, depending on the conjunction of three axes or decisional factors, the doctor can adopt four relationship styles with his patient: expert-in-charge, expert guide, partner and facilitator. The three decisional factors are: 1) the severity of the situation; 2) the critical or chronic health condition of the patient and 3) the patient’s willingness and ability to be co-responsible and collaborate to the diagnosis and treatment.

Hence, conceptualized around those three axes, the doctor-patient relationship can take various forms, such as a management consultant who seeks the best balance with his client between his role as expert and his role as facilitator, between the transmission of objective knowledge and the support given to the client to help him use his own experiential and tacit knowledge more effectively. Similarly, there is not only one possible relationship between doctors and patients. It opens the door to new attitudes and behaviors, depending of the decision made using the three decisional factors described above.

ASDH: arteriosclerotic heart disease, COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, DM: diabetic mellitus, GERD: gastroesophageal reflux disease, IBS: irritable bowel syndrome, MI: myocardial infarction, OA: osteoarthritis, RI: renal insufficiency, URTI: upper respiratory tract infection. *To check what type of relationship corresponds to a patient problem defined in terms of both the acute-chronic and minor-serious dimensions, one must project a perpendicular line on the collaboration continuum diagonal. For example, in the case of a URTI, the proposed relationship corresponds to the expert-guide type; whereas in the case of stable GERD, the relationship is more of the facilitator type. *Normal curve symbol represent possible variations in relationships resulting from setting and personal characteristics.

Figure 2. The possible transformations in the doctor-patient relationship: type of relationship is determined by problem and health care context. (Replicate with permission of the Canadian Family Physician Editors).

Therefore, doctors are invited to add a set of new relational abilities to their medical expertise, generally characterized by two key elements: 1) a “meta-competence”, which is the attitudinal and behavioral flexibility or ability to move from the traditional role of expert in charge to a role of partner or a role of facilitator depending of the situation; 2) the ability to master attitudes and behaviors associated with the roles of partner and facilitator and leading the doctor into the waters of sharing expertise with theirs patients.

This MD-patient relational model leads us to propose an exploratory Citizen-patients 3.0 behavioral profile that could help doctors assess if the situation and personal characteristics of their patients are in tune with the roles of partner or facilitator.

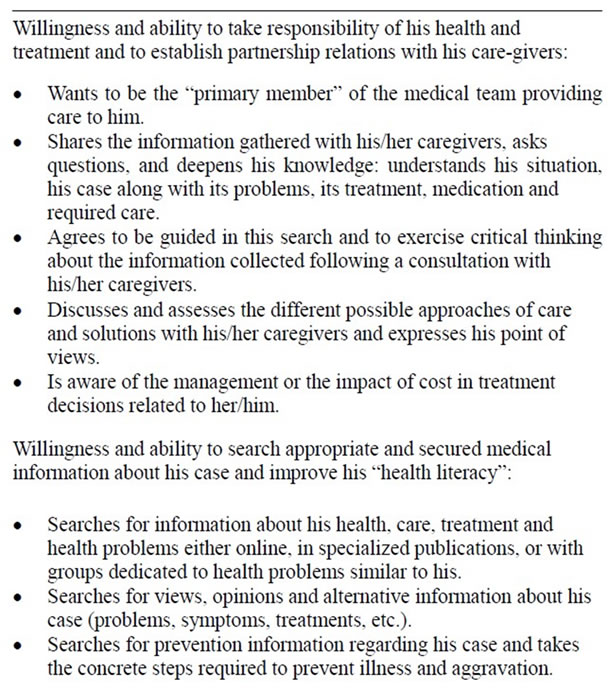

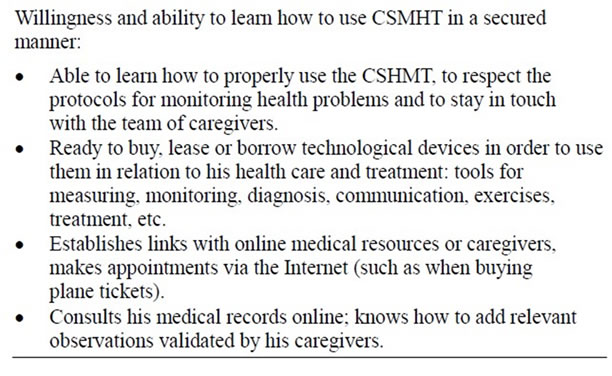

8. CITIZEN-PATIENTS 3.0 BEHAVIORAL PROFILE

A review of the work accomplished by the authors of the study “Patient of the Future” [19], by the European scientific André-Yves Portnoff [20], by Dr. Guy Pare who leads the Canadian Research Chair in Health Information Technology at HEC Montreal [21-23]; the review of writings related to models like Chronic Care Model [24], Expanded healthcare model [25] and in Focus [26]; the White Paper produced by the Ivey Centre for Innovation and Leadership in Health from the University of London Ontario [27] and the cutting-edge studies conducted in England [28], allows us to describe the profile of the citizenpatient 3.0. in a more precise manner.

Of course, the role of Patient 3.0 is particularly demanding. As well as the MDs 3.0 who are deeply challenged by the process of delegating responsibilities to the patient, the patient has to adopt them with all the implications of engagement and learning it represents. Legal aspects of patient’s increased accountability should also be addressed and framed explicitly. This last point is definitely the source of many legitimate preoccupations into the MDs profession regarding the movement of citizen-patients’ empowerment. With this in mind, we propose that the attitudinal and behavioral profile of the Citizen-patients 3.0 is a set of predispositions and abilities related to the three areas described in Table 1.

Table 1. Citizen-patient 3.0 behavioral profile.

The Patient 3.0 sees himself as a learner who continuously needs to acquire more knowledge and technical, interpersonal and personal skills in relation to his health and disease treatments. Therefore, a successful transition into the Health 3.0 paradigm will be based on “learning organizations” made up of administrators, doctors and managers who are “masters of change”, able to implement structural, cultural and professional transformations that foster autonomy, cooperation and co-responsibility about health and healthcare, in partnership with citizen-patients using certified CSMHT.

9. CONCLUSIONS

On the one hand, this paper suggests that the current period can lead to a new paradigm of care delivery called “Health 3.0”. This new context is characterized by:

![]() The exponential increase and practically uncontrollable demands in health services, either because of the aging population, citizen’s new life expectations or the continual expansion of healthcare services;

The exponential increase and practically uncontrollable demands in health services, either because of the aging population, citizen’s new life expectations or the continual expansion of healthcare services;

![]() The current limitations of our health system, whether in terms of costs for the society or in terms of available specialized resources;

The current limitations of our health system, whether in terms of costs for the society or in terms of available specialized resources;

![]() The availability of new health mechanisms, tools and technologies, which are increasingly accessible to more and more citizen-patients, as much in terms of costs as in terms of use;

The availability of new health mechanisms, tools and technologies, which are increasingly accessible to more and more citizen-patients, as much in terms of costs as in terms of use;

![]() Following the example of what is happening in other sectors such as traveling, financial, real estate, information services, etc., we witness the emergence of a new mentality of the citizen-patient which is manifested by the will of taking responsibilities that have always been taken on by healthcare institutions;

Following the example of what is happening in other sectors such as traveling, financial, real estate, information services, etc., we witness the emergence of a new mentality of the citizen-patient which is manifested by the will of taking responsibilities that have always been taken on by healthcare institutions;

![]() Well exploited by healthcare organizations, this paradigm shift can be seen as an incredible pool of new resources for the system with a large number of citizen-patients willing and able to qualify themselves as Patients 3.0.

Well exploited by healthcare organizations, this paradigm shift can be seen as an incredible pool of new resources for the system with a large number of citizen-patients willing and able to qualify themselves as Patients 3.0.

On the other hand, we suggest that it is important to establish favorable conditions rapidly and effectively in order to implement the Health 3.0 model of governance. These conditions, to name only a few are:

![]() The invention of a new clinician-patient relationship, which encourages the undertaking of an important part of healthcare responsibilities by patients with the support of various technological tools;

The invention of a new clinician-patient relationship, which encourages the undertaking of an important part of healthcare responsibilities by patients with the support of various technological tools;

![]() The specification of treatments that can be delegated and taught to patients as part of a secure and quality approach of care and treatments;

The specification of treatments that can be delegated and taught to patients as part of a secure and quality approach of care and treatments;

![]() The adaptation of caregivers’ remuneration in a respectable and mobilizing manner so they can assume their new mixed role of expert, partner and facilitator;

The adaptation of caregivers’ remuneration in a respectable and mobilizing manner so they can assume their new mixed role of expert, partner and facilitator;

![]() The modernization of laws, rules and modalities of practice governing medical acts and others so that citizens can assume an increasing part of responsibility in their healthcare without becoming a threat to caregivers;

The modernization of laws, rules and modalities of practice governing medical acts and others so that citizens can assume an increasing part of responsibility in their healthcare without becoming a threat to caregivers;

![]() The ongoing redefinition of the role of healthcare organizations in order to encourage medical leadership to reach a new balance between traditional intervenetions in institutions and interventions into the context of “connected clinics” promoting the tri-dimensional approach of Health 3.0 (clinicians and patients and CSMHT).

The ongoing redefinition of the role of healthcare organizations in order to encourage medical leadership to reach a new balance between traditional intervenetions in institutions and interventions into the context of “connected clinics” promoting the tri-dimensional approach of Health 3.0 (clinicians and patients and CSMHT).

It will be the citizen-patients in partnership with clinicians who will lead the transformation of our health system; otherwise the chronic problem of overflowing healthcare organizations will continue making the news for the same enduring reasons!

10. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Dr. Claude Richard, member of Marie-Therese Lussier research team, for his guidance in the production of the final version of this paper.

![]()

![]()

REFERENCES

- http://www.criso.ca/fr-CA/le-modele-sante-3-0-/

- Christensen, C.M., Bohmer, R. and Kenagy, J. (2000) Will disruptive innovations cure healthcare? Harvard Business Review, 102-112.

- Philippe Ameline. http://www.atoute.org/n/article150.html

- University of Montreal’s Faculty of Medicine. http://www.nouvelles.umontreal.ca/enseignement/faculte-de-medecine/20110105-innovation-pedagogique-a-la-faculte%20de-medecine-de-luniversite-de-montreal.html

- Cazale, L., Traoré, I. and Fournier, C. (2011) Les Qué- bécois atteints d’un problème de santé chronique entraînant des limitations d’activités sont-ils satisfaits des services de santé et des services sociaux reçus? Zoom Santé, 24.

- Roy, A.D., Litvak, E. and Paccaud, F. (2010) Des réseaux responsables de leur population. Moderniser la gestion et la gouvernance en santé. Le Point en administration de la santé et des services sociaux.

- Lussier, M.T., Turcotte, A., Richard, C., Lapointe, L. and Vedel, I. (2010) An evaluation of a patient-centred information technology tool for the management of chronic diseases by primary care interdisciplinary teams. ElectronicHealthcare, 8, e20-e25.

- Accenture (2010) More than two-thirds of US consumers seek medical advice via the internet and social media, accenture study finds. http://newsroom.accenture.com/article_display.cfm?article_id=5096.

- Glouberman, S. (2010) Est-il possible de prévoir les changements que les TI apporteront aux soins de santé? Santé en devenir, 33-36.

- Glouberman, S. (2010) My operation: A health insider becomes a patient. Health & Everything Publications, Toronto.

- CEFRIO (2010) La recherche d’information en ligne. Netendance, 1, 5-12.

- CRISO (2011) Ce qui se passe dans les universités québécoises en rapport avec Santé 3.0 (document interne, disponible sur demande).

- Inforoute Canada (2011) Imaginez une approche novatrice pour améliorer notre santé et nos soins de santé avec l’aide des technologies de l’information et des communications-que proposez-vous? https://www.infoway-inforoute.ca/lang-fr/about-infoway/news/news-releases/709-canadians-asked-how-health-care-can-be-improved-with-information-technology

- Quill, T.E. and Brody, H. (1996) Physician recommandations and patient autonomy: Finding a balance between physician power and patient choice. Annals of Internal Medecine, 125, 763-769.

- CHUM (2011) Faire tourner la roue des soins autrement (Dossier patient-partenaire). Chumagazine, 2, 16-21.

- Snowdon, A., Shell, J. and Leitch, K.K. (2010) Innovation takes leadership: Opportunities & challenges for Canada’s healthcare system. Ivey centre for health innovation and leadership. http://blogs.ivey.ca/ichil/files/2010/09/White-Paper.pdf

- The Health Foundation (2011) Closing the gap: Changing relationships. http://www.health.org.uk/public/cms/75/76/313/2257/Closing%20the%20Gap%20Changing%20Relationships%20project%20booklet.pdf?realName=Glo7f9.pdf

- Lussier, M.-T. and Richard, C. (2008) En l’absence de panacée universelle: Repertoire des relations médecinpatient. Canadian Family Physician, 54, 1096-1099.

- Burnand, B., Cathieni, F. and Peer, L. (2007) Le patient du futur: Volet suisse d’un projet européen. Lausanne, Raisons de santé, 132. http://www.iumsp.ch/Publications/pdf/rds132_fr.pdf

- Portnoff, A.-Y. (2007) Internet transforme les secteurs de la santé. Futuribles International, Vigie, note d’alerte 31.

- Lemire, M., Sicotte, C. and Paré, G. (2007) Internet et les possibilités de responsabilisation personnelle en matière de santé. Cahier de la Chaire de recherche du Canada en TI dans le secteur de la santé, 7.

- Paré, G., Malek, J.N., Sicotte, C. and Lemire, M. (2008) Le recours à internet en matière de santé personnelle et la responsabilisation du grand public. Cahier de la Chaire de recherche du Canada en TI dans le secteur de la santé, 8.

- Lemire, M., Paré, G. and Sicotte, C. (2006) Les déterminants du recours à Internet comme source d’information privilégiée en matière de santé personnelle. Cahier de la Chaire de recherche du Canada en TI dans le secteur de la santé, 6.

- Wagner, E.H., Austin, B.T., Davis, C., Hindmarsh, M., Schaefer, J. and Bonomi, A. (2001) Improving chronic illness care: Translating evidence into action. Health Affairs, 20, 64-78. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.20.6.64

- Barr, V.J., Robinson, S., Marin-Link, B., Underhill, L., Dotts, A., Ravensdale, D. and Salivaras, S. (2003) The expanded chronic care model: An integration of concepts and strategies from population health promotion and the chronic care model. Healthcare Quarterly, 7, 73-82.

- Réseau canadien de recherché pour les soins dans la communauté (2010) Supporting self managed care. http://www.ryerson.ca/crncc/knowledge/factsheets/pdf/SelfManaged_Care_In_Focus_Feb_2010.pdf

- Snowdon, A., Shell, J. and Leitch, K. (2011) Transforming canadian health care through consumer engagement: The key to quality and system innovation. Centre for Health, Innovation and Leadership. White Paper.

- Dixon, A. (2008) Engaging patients in their health. The King’s Fund, London.