Journal of Modern Physics

Vol.08 No.04(2017), Article ID:74606,9 pages

10.4236/jmp.2017.84028

On the Jefimenko’s Non-Einsteinian Clocks and Synchronicity of Moving Clocks

Andrew Chubykalo, Augusto Espinoza

Unidad Académica de Física, Universidad Autónoma de Zacatecas, Zacatecas, México

Copyright © 2017 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY 4.0).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received: February 3, 2017; Accepted: March 6, 2017; Published: March 9, 2017

ABSTRACT

In this work we analyze the concept of time dilation in its application to the rate of moving clocks. The rates of two equiform elementary electromagnetic clocks of different orientations relative to their direction of motion are computed on the basis of relativistic transformations of force and coordinates for the case when the clocks are at rest in a stationary reference frame and for the case when they are moving at constant speed relative to the stationary reference frame. It is shown that, although both clocks run slower when they are moving than when they are at rest, the rate of the moving clocks is affected by their orientation relative to their direction of motion, rather than by the kinematic (relativistic) time dilation as it is now generally assumed. The implication of this result for the experimental proofs of the existence of the kinematic the dilation is discussed.

Keywords:

Synchronicity, Time Dilation, Length Contraction

1. Introduction

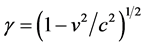

Albert Einstein in his famous 1905 paper interpreted the Lorentz transformation equations for coordinates and time as indicating that time is kinematically “dilated” in systems that move with respect to the systems considered to be stationary [1] . As a physical entity, time is defined in terms of specific measurement procedures, which may be described simply as “observing the rate of clocks”. It is now generally assumed that because of time dilation, the rate of all moving clocks is slower by the factor  than the rate of the same stationary clocks. However, a clock is a physical apparatus or device and is subject to the laws of physics in accordance with which the clock is constructed. Therefore, if a clock slows down when it moves, its slower rate should be explainable on the basis of the specific laws responsible for the operation of the clock and on the basis of relativistic transformations applicable to these laws.

than the rate of the same stationary clocks. However, a clock is a physical apparatus or device and is subject to the laws of physics in accordance with which the clock is constructed. Therefore, if a clock slows down when it moves, its slower rate should be explainable on the basis of the specific laws responsible for the operation of the clock and on the basis of relativistic transformations applicable to these laws.

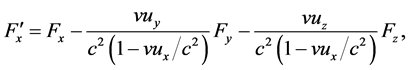

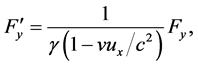

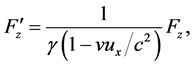

In particular, if mechanical or electromagnetic forces are involved in the operation of a clock, then the rate of the moving clock should be explainable on the basis of these forces and on the basis of the relativistic force transformation equations (for the derivation of these equations see, for example, [2] )

(1)

(1)

(2)

(2)

(3)

(3)

where the primes indicate force components observed in a moving frame; the unprimed quantities are quantities observed in the stationary reference frame (laboratory);  is the velocity of the moving reference frame relative to the laboratory;

is the velocity of the moving reference frame relative to the laboratory;  is the

is the  -component of the velocity of the force-experiencing object relative to the laboratory; and

-component of the velocity of the force-experiencing object relative to the laboratory; and  is the velocity of light.

is the velocity of light.

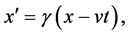

Furthermore, if the functioning of a clock depends on its geometrical para- meters, then the rate of the moving clock may depend on the relativistic transformation equations for coordinates [2]

(4)

(4)

(5)

(5)

(6)

(6)

In this connection it is important to note that in Equations (1)-(6) the x components transform differently from the  and

and  components. Therefore, if two synchronous stationary clocks, one oriented in the

components. Therefore, if two synchronous stationary clocks, one oriented in the  direction, the other oriented in the

direction, the other oriented in the  or

or  direction, are placed in a moving reference frame, the clocks may become asynchronous in that reference frame, because both the forces acting on differently oriented clocks and the linear dimensions of differently oriented clocks will transform differently.

direction, are placed in a moving reference frame, the clocks may become asynchronous in that reference frame, because both the forces acting on differently oriented clocks and the linear dimensions of differently oriented clocks will transform differently.

The purpose of this paper is to verify the above considerations regarding the rate of moving clocks by actual calculations and to discuss the implication of the obtained results for the experimental proof of kinematic time dilation. In the calculations that follow, we shall compute and compare the rates of two stationary elementary electromagnetic clocks with the rates of the same moving clocks. The operation of our clocks will be based on the interaction between a field-experiencing electric point charge and different field-producing electric point charge configurations.

2. Calculations

Clock #1. Consider two positive point charges  of the same magnitude located at the points

of the same magnitude located at the points  of the

of the

The electric field produced by the charges

where

This is a linear restoring force. Therefore our system of the three charges constitutes a simple harmonic oscillator, and the charge

Clearly, this system of the three charges may be considered to constitute a clock and can be used for measuring time in terms of the period of oscillations

Let us now assume that the three charges are placed in a reference frame moving along the

Figure 1. A negative point charge

To find the force acting on

from which we obtain

Substituting Equation (10) into Equation (12) and taking into account that, by Equations (5) and (6)2,

Taking into account that the mass of the moving charge

and using Equation (9) with

Comparing Equation (15) with Equation (9), we find that

so that the rate of our moving clock #1 is longer by the factor

Clock #2. This clock is the same as clock #1 except that the field-producing charges

Clearly, when clock #2 is at rest in the laboratory reference frame, the period of oscillations of

Figure 2. A negative point charge

Let us now assume that clock #2 is placed in a reference frame moving along the

To find the force acting on the moving

from which we again obtain

Substituting Equation (18) into Equation (20) we have

where we still need to transform

First we notice that, by Equation (5),

To find the relation between

Let the time of observation in the laboratory be

and

The distance between the two charges measured in the moving reference frame is then, by Equations (24), (25) and (23),

and hence

Substituting

Taking into account that the mass of the moving charge

and using Equation (17) with

Comparing Equation (30) with Equation (17), we find that for clock #2

so that, in contrast to Clock #1, the rate of the moving Clock #2 is dilated by the factor

3. Discussion

The calculations just presented reveal two properties of the rate of moving clocks: 1) moving clocks run slower than the same stationary clocks; 2) differently constructed (or oriented) synchronous stationary clocks may run at different rates and therefore may become asynchronous when placed into a moving reference frame. Quantitatively, our first clock behaves in accordance with the idea of the kinematic (relativistic) time dilation (the moving clock runs

As is known, the electric field produced by a moving point charge concen- trates itself about the plane perpendicular to the direction of motion and decreases along the line of motion (see, for example [4] ). Therefore, as seen by a stationary observer, the electric force acting on the charge

It may at first appear that the principle of relativity is violated by the fact that synchronous stationary clocks may become asynchronous when moving. This is not so. According to the principle of relativity, it is impossible to tell whether a particular inertial reference frame is “actually” moving or is stationary. The fact that synchronous clocks may become asynchronous when placed in a “moving” reference frame does not tell us which of the two frames is really moving, because the effect is reciprocal. It is easy to see that if we started with synchro- nous clocks resting in the “moving” reference frame, then placed them into the “stationary” reference frame and used transformation equations expressing unprimed force components and coordinates in terms of primed quantities, we would find that the clocks placed in the “stationary” reference frame would not be synchronous when viewed from the “moving” reference frame. Thus placing synchronous clocks into a different reference frame and finding that the clocks become then asynchronous provide no information on whether or not one or the other of these reference frames is “actually” moving or is stationary, which is in complete agreement with the principle of relativity.

There is, however, an important implication result as far as the proofs of the existence of the kinematic (relativistic) time dilation are concerned. It is now generally believed that the existence of kinematic time dilation has been demonstrated by actual experiments [6] [7] [8] . As has been already pointed out by Jefimenko [9] , and as is clear from the calculations presented in this paper, the experiments that are interpreted as proofs of the reality of kinematic time dilation may have a simple alternative interpretation in terms of velocity- dependent forces present in the systems under consideration. Of course, we do not know what forces are responsible for the decay of elementary particles and we know little about the forces responsible for the functioning of atomic clocks. But there can be no doubt that the decay of elementary particles, as well as the action of atomic clocks, is controlled by some kind of forces. In the light of the calculations presented in this paper and of similar calculations presented else- where [5] [9] , it is much more natural and prudent to interpret the experiments allegedly proving the reality of kinematic time dilation as manifestations of the existence of velocity-dependent forces and interactions in the systems under consideration.

Moreover, it is now clear that to prove the reality of kinematic time dilation it is necessary not only to demonstrate that moving clocks run slower by the factor

In conclusion, in connection with the above, we would like to adduce here (or propose to consider) a curious paradox:

Imagine that in the system

It is obvious that

As for the “Jefimenko’s cat” yet it is not a “point of view”. According to our calculations, the non-synchronicity of clocks is a purely objective phenomenon. Its essence is that stationary systems and moving systems are different physical systems, and so the physical phenomena occur in them in different ways.

Cite this paper

Chubykalo, A. and Espinoza, A. (2017) On the Jefimenko’s Non-Einsteinian Clocks and Synchronicity of Moving Clocks. Journal of Modern Physics, 8, 439-447. https://doi.org/10.4236/jmp.2017.84028

References

- 1. Einstein, A. (1905) Annals of Physics, 17, 891-921.

https://doi.org/10.1002/andp.19053221004 - 2. French, A.P. (1968) Special Relativity. Norton, New York, 237.

- 3. Goldstein, H. (1951) Classical Mechanics. Addison-Wesley, Cambridge, 205.

- 4. Jackson, J.D. (1999) Classical Electrodynamics. 3rd Edition, Wiley, New York, 559-561.

- 5. Jefimenko, O.D. (2004) Electromagnetic Retardation and the Theory of Relativity. 2nd Edition, Electret Scientific, Star City, 237-244, 251-253.

- 6. Rossi, B. and Hall, D.B. (1941) Physical Review, 59, 223.

Fisch, D.H. and Smith, J.H. (1963) American Journal of Physics, 31, 342.

Bailey, J., Borer, K., Combley, F., Drumm, H., Krienen, F., Lange, F., Picasso, E., von Ruden, W., Farley, W.J.M., Field, J.H., Flegel, W. and Hattersley, P.M. (1977) Nature, 268, 301. - 7. Hafele, J.C. and Keating, R.E. (1972) Science, 177, 166, 168.

- 8. Takabayashi, Y. (2001) High Precision Spectroscopy of Helium-Like Heavy Ions with Resonant Coherent Excitation. Doctor Thesis, Tokyo Metropolitan University, Tokyo.

- 9. Jefimenko, O.D. (1998) Z. Naturforsch, 53a, 977.

Jefimenko, O.D. (1998) American Journal of Physics, 63, 454.

https://doi.org/10.1119/1.17911

NOTES

1The charge must be constrained to stay on the axis because otherwise it is unstable with respect to a lateral displacement.

2Observe that

3In his book [5] Jefimenko adduces also other kinds of clocks that do not run in accordance with Einstein’s theory, e.g.,

4In this system time is measured by the “