Journal of Modern Physics

Vol.06 No.14(2015), Article ID:60894,4 pages

10.4236/jmp.2015.614204

Massive Galaxies and Central Black Holes at z = 6 to z = 8

T. R. Mongan

84 Marin Avenue, Sausalito, CA, USA

Copyright © 2015 by author and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

Received 21 September 2015; accepted 2 November 2015; published 5 November 2015

ABSTRACT

In a closed vacuum-dominated universe, the holographic principle implies that only a finite amount of information will ever be available to describe the distribution of matter in the sea of cosmic microwave background radiation. When z = 6 to z = 8, if information describing the distribution of matter in large scale structures is uniformly distributed in structures ranging in mass from that of the largest stars to the Jeans’ mass, a holographic model for large scale structure in a closed universe can account for massive galaxies and central black holes observed at z = 6 to z = 8. In sharp contrast, the usual approach assuming only collapse of primordial overdensities into large scale structures has difficulty producing massive galaxies and central black holes at z = 6 to z = 8.

Keywords:

Large Scale Structure, Holography, Early Galaxies, Early Supermassive Black Holes

1. Introduction

“Current theory predicts that galaxies begin their existence as tiny density fluctuations, with overdensities collapsing into virialized protogalaxies, and eventually assemble gas and dust into stars and black holes” [1] . Steinhardt et al. [1] summarized data indicating that the current approach had difficulty accounting for massive galaxies and their associated central black holes at redshifts  to

to .

.

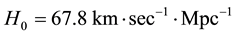

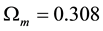

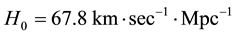

To address the “impossibly early galaxy problem” of Steinhardt et al., this analysis treats our universe as a closed Friedmann universe, dominated by vacuum energy in the form of a cosmological constant, and so large that it is approximately flat. This is consistent with full mission 2015 Planck satellite observations [2] indicating that the universe is dominated by vacuum energy, spatially flat to a good approximation, with Hubble constant , total matter density

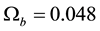

, total matter density , and baryonic density

, and baryonic density . Adler and Overduin [3] claimed “observation cannot distinguish―even in principle―between a perfectly flat universe and one that is sufficiently close to flat.” However, analysis assuming a closed inflationary universe and accounting for important features of large scale structure may indicate that our universe is closed.

. Adler and Overduin [3] claimed “observation cannot distinguish―even in principle―between a perfectly flat universe and one that is sufficiently close to flat.” However, analysis assuming a closed inflationary universe and accounting for important features of large scale structure may indicate that our universe is closed.

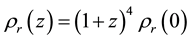

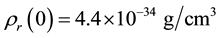

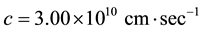

In the following,  is the cosmic microwave background (CMB) radiation density at redshift z, where

is the cosmic microwave background (CMB) radiation density at redshift z, where  and the mass equivalent of today’s radiation energy density

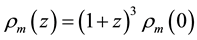

and the mass equivalent of today’s radiation energy density  [4] , the matter density at redshift z is

[4] , the matter density at redshift z is  where

where  is today’s matter density, and

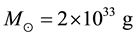

is today’s matter density, and

is the solar mass. With Hubble constant

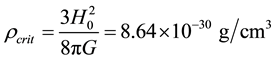

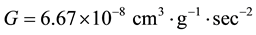

is the solar mass. With Hubble constant , the critical density

, the critical density

, where

, where  and

and . Since

. Since

matter accounts for 30.8% of the energy in today’s universe,

In a closed universe, there is no source or sink for information outside the universe, so the total amount of information available to describe the universe remains constant. Also, after the first few seconds of the life of the universe, energy exchange between matter and radiation is negligible compared to the total energy of matter and radiation separately [6] . Therefore, in a closed universe, the total quantity of matter in the universe is conserved; there is only a fixed amount of information available; and the average mass per bit of information is constant. In a closed, isotropic, and homogeneous Friedmann universe, the constant mass per bit of information

(the mass

information within the event horizon) is

2. Galaxies at z = 6 to z = 8

At

When the matter density

waves affecting matter density is

In this holographic model for large scale structure at

uses a maximum stellar mass of

horizon relates to the aggregate of halo masses by

While recognizing the difficulties and intricacies involved in estimating halo masses at large redshift, Steinhardt et al. [1] present their estimates for the number of halos in a volume

mass between

between

The scale factor

Compared to the cloud of data points in Figure 1 of Steinhardt et al. [1] showing their estimated halo densities, the above results are slightly below the cloud at

3. Black Holes at z = 6 to z = 8

As in Ref. [7] , it is assumed an isothermal spherical halo of dark matter with mass MS is enclosed by a holo-

graphic screen with radius

where r is the distance from the center of the halo and a is constant. The mass

radius Rs in an isothermal density distribution is

If the mass of the central supermassive black hole (SMBH) is at the center of a core volume with radius

Mortlock et al. [11] found a black hole with mass

4. Conclusion

Caltech’s Professor Steinhardt and colleagues [1] discussed the “impossibly early galaxy problem,” reviewing data showing that the conventional approach to formation of large scale structure cannot adequately account for presence of the massive galaxies and associated central black holes observed at redshifts z = 6 to z = 8. In sharp contrast, the holographic analysis outlined above requires supermassive black holes with mass on the order of

Cite this paper

T. R.Mongan, (2015) Massive Galaxies and Central Black Holes at z = 6 to z = 8. Journal of Modern Physics,06,1987-1990. doi: 10.4236/jmp.2015.614204

References

- 1. Steinhardt, C., et al. (2015) The Impossibly Early Galaxy Problem. arXiv:1506.01377.

- 2. Planck Collaboration (2015) Planck 2015 Results. XIII. Cosmological Parameters. arXiv:1502.01589.

- 3. Adler, R. and Overduin, J. (2005) General Relativity and Gravitation, 37, 1491. [gr-qc/0501061]

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10714-005-0189-6 - 4. Siemiginowska, A., et al. (2007) Astrophysical Journal, 657, 145.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/510898 - 5. Bousso, R. (2002) Reviews of Modern Physics, 74, 825.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1103/RevModPhys.74.825 - 6. Misner, C., Thorne, K. and Wheeler, J. (1973) Gravitation. W. H. Freeman and Company, New York.

- 7. Mongan, T. (2012) Holography, Large Scale Structure, Supermassive Black Holes and Minimum Stellar Mass. arXiv:1301.0304.

- 8. Longair, S. (1998) Galaxy Formation. Springer-Verlag, Berlin.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-3-662-03571-9 - 9. Crowther, P. (2010) The R136 Star Cluster Hosts Several Stars Whose Individual Masses Greatly Exceed the Accepted 150 Msun Stellar Mass Limit. arXiv:1007.3284.

- 10. Massey, P. and Meyer, R. (2001) Stellar Masses. Encyclopedia of Astronomy and Astrophysics.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1888/0333750888/1882 - 11. Mortlock, D. (2011) Nature, 474, 616. [arXiv:1106.6088]

http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nature10159 - 12. Pacucci, F., Volonteri, M. and Ferrara, F. (2015) The Growth Efficiency of High-Redshift Black Holes. arXiv: 1506.04750.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/mnras/stv1465 - 13. Trakhtenbrot, B., et al. (2015) Science, 349, 168. [arXiv:1507.02290]

http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.aaa4506