Psychology

Vol.5 No.5(2014), Article ID:44614,7 pages DOI:10.4236/psych.2014.55042

Self-Affirmation Buffers Claimed Self-Handicapping? A Test of Contextual and Individual Moderators

Sarah Tandler1, Malte Schwinger2, Kristina Kaminski1, Joachim Stiensmeier-Pelster1

1Department of Psychology, University of Giessen, Giessen, Germany

2Department of Psychology, Marburg University, Marburg, Germany

Email: malte.schwinger@uni-marburg.de

Copyright © 2014 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received 26 January 2014; revised 23 February 2014; accepted 21 March 2014

ABSTRACT

Researchers have argued that the strategies individuals use for self-esteem regulation are interchangeable. In the present study, we examined whether previous self-affirmation reduces the amount of subsequent claimed self-handicapping. More importantly, we tested potential moderators of these effects. Following negative feedback on an intelligence test, 56 female college students were given the opportunity to affirm themselves either within the threatened intelligence domain or within a domain unrelated to the source of threat (e.g., musicality). Results revealed that subjects handicapped less when they had previously affirmed themselves in a domain which was unrelated to the threatening domain (contextual moderator). However, these effects were moderated by dispositional self-esteem (individual moderator). High self-esteem participants claimed fewer handicaps the more they felt self-affirmed whereas claimed self-handicapping among low self-esteem participants was not affected by previous self-affirmation. Altogether, our findings suggest certain limitations on the substitutability of self-protection processes.

Keywords

Self-Handicapping, Self-Affirmation, Self-Esteem, Self-Regulation

1. Introduction

Most of the literature on self-esteem regulation has examined antecedents and consequences of single regulation strategies, e.g. (Zuckerman & Tsai, 2005). In contrast, issues such as how many strategies are needed to effectively protect or restore one’s self-esteem, or whether using one strategy may compensate for the use of another, have received little attention. Some studies have shown that self-affirmation (Steele, 1988) can reduce the additional application of further regulation strategies (e.g., Cohen, Aronson, & Steele, 2000). With the present study, we contribute to this line of research by examining the effects of self-affirmation on subsequent self-handicapping (McCrea & Hirt, 2011; Siegel, Scilitoe, & Parks-Yancy, 2005). More importantly, we seek to analyze contextual and individual moderators of these effects. First, we assume that self-affirmation, by valuing an aspect of the self which is unrelated to the threat, is more effective in reducing self-handicapping compared to valuing an aspect of the self which is currently threatened (contextual moderator; McCrea & Hirt, 2011). Second, we aim to provide evidence that a person’s dispositional self-esteem moderates the compensatory impact of self-affirmation on self-handicapping (individual moderator).

1.1. Using Self-Affirmation to Reduce Self-Handicapping

Given its wide ranging negative implications like low academic performance or decreased personal well-being, e.g. (Zuckerman & Tsai, 2005), it is important to identify conditions under which self-handicapping is less likely to occur. Surprisingly, there are only a few studies concerned with this topic, e.g. (Shepperd & Arkin, 1989). A promising way to decrease self-handicapping is to regulate one’s self-esteem through alternative self-esteem maintenance mechanisms. Some authors postulated a substitutability of different forms of self-esteem regulation (Tesser, Crepaz, Collins, Cornell, & Beach, 2000). In their view, each self-protective strategy is used with the same goal in mind, so the different strategies describe different ways of buffering self-esteem. Consequently, regulating self-esteem through one mechanism should reduce the likelihood of engaging in a second mechanism (Tesser et al., 2000). Self-affirmation theory postulates that negative reactions to self-esteem threats can be reduced by thoughts and actions affirming some other valued aspect of the self (Steele, 1988). A number of studies have shown that participants were less likely to rationalize self-threatening behavior when they had already affirmed some other relevant aspect of the self, e.g. (Cohen, Aronson, & Steele, 2000). Drawing on this research, we reason that the opportunity to self-affirm might also diminish the tendency to self-handicap. Support for this hypothesis has already been found in two studies (McCrea & Hirt, 2011; Siegel et al., 2005). However, yet available findings are limited in several ways. For instance, self-esteem threat was not experimentally induced and only few specific forms of handicaps have been examined. In our study, we focus on claimed rather than behavioral self-handicapping since we consider it the much stronger test of the buffering potential of self-affirmation. Behavioral handicaps entail costs, namely real impairment for good performance. In self-threatening situations, these costs have to be outweighed against the positive effects of self-worth regulation. As a consequence, previous self-affirmation might reduce the use of behavioral handicaps as soon as self-esteem threat has been diminished to the degree that additional handicapping would not be worth the associated costs. Claimed self-handicapping, in contrast, entails no direct costs which had to be outweighed against positive effects. So there is no reason why people should not play it safe and use claimed self-handicapping additionally by default. Consequently, previous self-affirmation might reduce subsequent claimed self-handicapping only then if it has ruled out every little piece of self-doubt in the respective individual. Stated differently, there is much stronger support for the substitutability hypothesis if self-affirmation can reduce claimed rather than behavioral selfhandicapping.

1.2. Contextual Moderators

The effectiveness of self-affirmation seems to be influenced by the domain in which affirmation takes place (McCrea & Hirt, 2011). According to the self-standards model of cognitive dissonance (SSM, Stone & Cooper, 2003), positive information about the self may not always have positive effects since it can serve as a resource or a standard needing to fit within one’s current behavior (Aronson, Blanton, & Cooper, 1995). Focusing on an important aspect of the self may serve as a resource for self-affirmation as long as it is unrelated to the threatened domain. In contrast, focusing on an aspect related to the source of self-esteem threat may increase the perception of threat because it refers to the violated standard. These findings imply that self-affirmation is successful in decreasing self-handicapping, but only if individuals focus on aspects of the self which are unrelated to the source of threat (McCrea & Hirt, 2011; Siegel et al., 2005).

1.3. Individual Moderators

In addition to context effects, individual personality traits might also play a central moderating role in the effectiveness of self-esteem regulation. Here, we hypothesize that the buffering effects of self-affirmation on selfhandicapping are moderated by level of self-esteem. According to the SSM, discrepancy between behavior and personal standards motivates self-protection processes. Individuals with high vs. low self-esteem differ in the extent to which they perceive such discrepancies. Individuals with high self-esteem who have positive expectancies for their behavior are more likely to perceive poor performance as a discrepancy to their self-standards and experience more self-esteem threat than individuals with low self-esteem who presumably hold less positive self-images and more negative expectancies for their behavior (Stone & Cooper, 2001). Thus, if positive selfattributes relevant to the threatened domain are made accessible, high self-esteem individuals may not feel self-affirmed because violated personal standards for competent behavior become salient. Consequently, they still experience high self-esteem threat and the need for further protection by claimed self-handicapping. In contrast, people with low self-esteem perceive negative performance as more consistent to their negative expectations which is why positive information about the self in the threatened domain may neither increase the actual self-esteem threat nor heighten the likelihood to engage in claimed self-handicapping (cf. Stone & Cooper, 2003).

1.4. The Present Research

In this study, we hypothesize the buffering effects of self-affirmation on self-handicapping to be moderated by contextual conditions (self-affirmation condition: threat-related vs. threat-unrelated self-aspect) as well as by individual characteristics (level of self-esteem). Self-esteem threat was experimentally induced by negative performance feedback on the training section of an upcoming intelligence test. Following negative performance feedback, participants were given the opportunity to affirm themselves either within the threatened domain or within a domain unrelated to the source of threat. After having affirmed themselves, but before the real IQ-test, participants were given the chance to self-handicap by claiming performance inhibiting factors. We predicted that subjects in the threat-unrelated affirmation condition would self-handicap less than participants in the threat-related condition (Hypothesis 1). Furthermore, we expected that high self-esteem individuals show a significant decrease in claimed self-handicapping the more they feel self-affirmed. This decrease in claimed selfhandicapping is assumed to be significantly smaller for low self-esteem individuals (Hypothesis 2).

2. Method

2.1. Sample

To eliminate potential gender biases, we decided to choose a clearly female sample. Participants included 56 female students (age: M = 21.55 years, SD = 3.66) recruited from several introductory courses at a German university. The majority of the students were enrolled in Physical Activity and Health (82.1%) and in their first year at university (87.5%). However, we did not assume that the attendance of different college courses might influence the results in any regard. Students participated in exchange for extra course credits.

2.2. Measures and Procedure

2.2.1. Individual Moderator Variables

In a mass testing session several weeks before the experiment, students completed a questionnaire including demographic items and the German version of the Rosenberg scale assessing their level of self-esteem (Ferring & Filipp, 1996). The Rosenberg self-esteem scale consists of 10 items with Likert scales ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The self-esteem scale showed a good internal consistency of α = .85. Furthermore, subjects were asked to rank nine personal characteristics on their importance to their self-integrity (1 = least important, 9 = most important). The inventory of personal characteristics was comprised of the following dimensions (according to Aronson et al., 1995): honesty, athleticism, intelligence, physical attractiveness, creativity, sociability, studiousness, helpfulness, and musicality. Participants made two ratings for each of the nine personal characteristics. First, subjects were asked how much each trait applies to themselves on a scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Next, students rated the personal importance for each dimension (e.g., “How important is being honest to you?”) on scales ranging from 1 (not important) to 5 (very important).

2.2.2. Cover Story

The experimenter explained that several studies had shown some personality traits to be associated with low values in intelligence tests. To create a self-relevant situation, participants were told that there was a link between low intelligence and the personality dimension they rated as second most important1. For example, honest people were deemed less intelligent for individuals who had rated honesty as the second most important domain. Next, the experimenter explained that participants would take an intelligence test with a preceding training section in order to further examine the relation between personality and intelligence.

2.2.3. Intelligence Test and Feedback

Test items consisted of matrices tasks selected from the I-S-T 2000 R (Amthauer, Brocke, Liepmann, & Beauducel, 2001). At first, all subjects were shown two easy sample items. They were told that they would have to complete an intelligence test with similar, but more difficult tasks. Furthermore, they were informed that they would get the chance to practice those items in a training section prior to the intelligence test in order to be well prepared for the IQ-test. Then the training section of the intellectual test began. Participants had five minutes for eight tasks. After completion of the training section, all participants received false negative feedback about their performance: “Your score falls in the 14th percentile. This means that 86% of students your age taking this test performed better than you”2.

2.2.4. Self-Affirmation Manipulation

After the negative feedback, participants were given the opportunity to affirm themselves in order to eliminate threats to their self-esteem. Subjects were randomly assigned to either the personality or the intelligence condition. We assumed that subjects in the personality condition would be able to regulate self-esteem threat by affirming a self-aspect unrelated to the threatened domain (Aronson et al., 1995). Therefore, they received the instruction to write a short essay about a specific personality dimension. This dimension was selected according to the participants’ previous ratings, i.e., we selected the dimension which had been rated as most important by the individual student3. The following instructions were given: “1) Please briefly describe what this personality dimension means for you; 2) What is your attitude toward this construct? How important is it and why?” In the intelligence condition, participants were requested to write a short essay about intelligence. They were informed that the experimenter had special interest in their everyday conception of intelligence. Questions equivalent to those in the personality condition were presented.

2.2.5. Claimed Self-Handicapping

Following the self-affirmation procedure, the investigator explained that some factors could inhibit participants’ performance in the intelligence test. For this reason they would be allowed to claim potentially inhibiting factors before the test began. On a Likert-type scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree), subjects declared whether bad mood, fatigue, illness, test anxiety, reduction in intended effort, distress, distraction, and excitement actually impaired their performance. After participants were given the opportunity to claim self-handicapping, they completed the IQ-test. Once again, they had five minutes for eight matrices tasks.

2.2.6. Claimed Self-Affirmation

To get a measure of how far subjects had been successful in self-affirmation, we asked participants to describe how they felt during the writing of the short essay about intelligence or the other personality construct, respectively (Siegel et al., 2005). The response scale ranged from 1 (very uncomfortable) to 5 (very comfortable).

3. Results

3.1. Main Effects of Self-Affirmation

A linear regression analysis revealed affirmation condition as a significant predictor of claimed self-handicapping (β = 0.41, t[59] = 3.45, p < 0.01). Participants who were given the opportunity to affirm themselves within a domain unrelated to the source of threat (personality condition) claimed less handicaps (M = 0.93, SD = 0.97) than subjects who affirmed themselves in the threatened domain (intelligence condition; M = 1.81, SD = 0.99). Likewise, the claimed self-affirmation, i.e. the degree to which participants stated the essay writing as comfortable, was also significantly related to less claimed self-handicapping (r = −0.29, p < 0.05). Supplemental mediation analyses revealed a significant indirect effect of affirmation condition on claimed self-handicapping (Bootstrapping 90% CI [0.01, 0.28], p = 0.07), indicating a partial mediation effect for claimed self-affirmation.

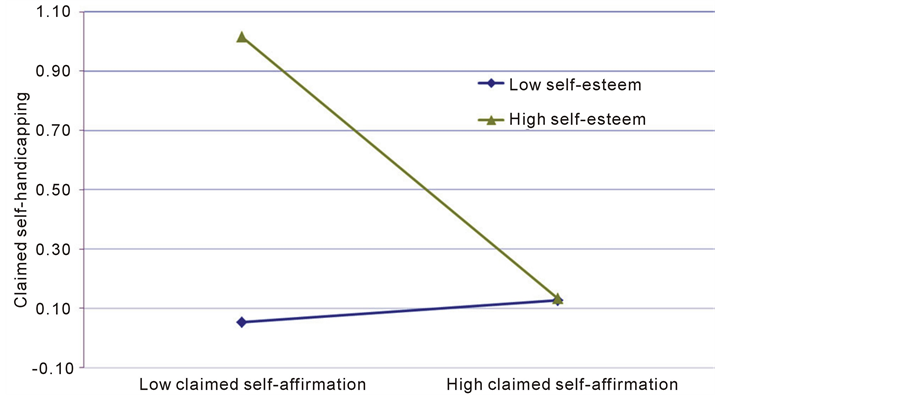

3.2. Interaction Effects of Self-Affirmation and Self-Esteem

The self-esteem scale showed a good internal consistency of α = 0.85. Preliminary ANOVAs revealed no pre-test differences in self-esteem between the two experimental groups (F[1, 58] = 1.84, p = 0.18). We firstly conducted a regression analysis with affirmation condition as independent variable and self-esteem as moderator. This regression model revealed a significant main effect for affirmation condition at Step 1 (β = .39, p < 0.01), but a non-significant effect for the interaction term with self-esteem at Step 2 (β = 0.12, p > 0.10). However, since claimed self-affirmation was found to significantly mediate the effect of affirmation condition, we conducted a second regression analysis with claimed self-affirmation as independent variable and self-esteem as moderator. This model revealed a significant main effect for claimed self-affirmation at Step 1 (β = −0.28, p < 0.05) as well as a significant effect for the interaction term at Step 2 on subjects’ amount of claimed self-handicapping (β = −0.21, p < 0.05 one-tailed). For individuals high in self-esteem (i.e., 1 SD above the mean), simple slope analyses indicated a significant effect of claimed self-affirmation on claimed self-handicapping (B = −0.55, SE = 0.19, t[52] = −2.89, p < 0.01). However, for those individuals low in self-esteem (i.e., 1 SD below the mean), claimed self-affirmation was unrelated to claimed self-handicapping (B = −0.02, SE = 0.20, t[52] = −0.08, p = 0.93; see Figure 1).

4. Discussion

4.1. Contextual and Individual Moderators

Our findings resemble previous studies (Aronson et al., 1995; McCrea & Hirt, 2011) since they indicate that the perception of threat was amplified by writing and reflecting about intelligence while overall self-esteem was reinforced by writing about an unrelated valued aspect of the self in the personality condition. Self-affirmation by focusing on a valued aspect of the self unrelated to the source of threat thus seems to be more effective in reducing self-handicapping compared to affirming a threat-related aspect of the self. In support of the substituta

Figure 1. Claimed self-handicapping as a function of claimed self-affirmation and level of self-esteem.

bility hypothesis (Tesser et al., 2000), these results show that self-esteem regulation mechanisms are interchangeable. At least domain-unrelated self-affirmation can turn off self-handicapping, probably because overall self-esteem has been successfully regulated, even without eliminating the original threat. However, we do not know if this compensating effect can be generalized to all self-protective strategies or if it is exclusively assigned to self-affirmation (Tesser et al., 2000). Moreover, substitutability may be limited to certain contextual conditions like the here examined threat-related affirmation condition or the opportunity to redress a threat directly (Stone, Wiegand, Cooper, & Aronson, 1997).

The results also prove evidence that individual differences in self-esteem level moderate the effect of self-affirmation on self-handicapping. The tendency to self-handicap was reduced by self-affirmation only for subjects with high self-esteem. People with high self-esteem are supposed to dispose of many favorable self-aspects. Stated differently, their overall self-esteem depends less on one particular self-aspect. Therefore, individuals might restore self-esteem rather easily by affirming another positive self-aspect. Consequently, they do not need further intensification of self-esteem protection by self-handicapping. Notably, however, the assumed moderator effect of self-esteem was only observed for claimed self-affirmation as predictor, not for affirmation condition. Future studies which replicate this effect are therefore clearly needed.

4.2. Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research

There are some limitations of this study. First, the effects of self-affirmation on self-handicapping were investigated under experimental conditions. It is therefore possible that the findings would have been different if measured in school, workplace, or competitive sport contexts. Second, due to the small number of male subjects in the present research, we did not account for gender differences. Future studies should include more balanced samples to investigate potential gender differences. Finally, we manipulated evaluative feedback in the domain of intelligence. Further research may test the substitutability of self-esteem regulation strategies in other ego relevant contexts, such as social relationships. An important issue for future research might be to examine how far other self-esteem regulation strategies can also prevent persons from engaging in self-handicapping. Moreover, it might be promising to include stability and contingency of self-esteem into the list of individual moderators (Kernis, 2003).

4.3. Conclusion

The present study underlines the substitutability hypothesis proposed by Tesser et al. (2000) as previous self-affirmation was found to reduce the amount of subsequent self-handicapping. However, our findings also suggest certain limitations on the substitutability of self-protection processes. Both participants’ individual self-esteem and contextual conditions moderated the degree of substitutability in our sample.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Anastasia Byler for copyediting.

References

- Amthauer, R., Brocke, B., Liepmann, D., & Beauducel, A. (2001). Intelligenz-Struktur-Test 2000 R. Göttingen: Hogrefe.

- Aronson, J., Blanton, H., & Cooper, J. (1995). From Dissonance to Disidentification: Selectivity in the Self-Affirmation Process. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 68, 986-996. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.68.6.986

- Cohen, G. L., Aronson, J., & Steele, C. M. (2000). When Beliefs Yield to Evidence: Reducing Biased Evaluation by Affirming the Self. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 26, 1151-1164. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/01461672002611011

- Ferring, D., & Filipp, S.-H. (1996). Messung des Selbstwertgefühls: Befunde zu Reliabilität, Validität und Stabilität der Rosenberg-Skala. Diagnostica, 42, 284-292.

- Kernis, M. H. (2003). Toward a Conceptualization of Optimal Self-Esteem. Psychological Inquiry, 14, 1-26. http://dx.doi.org/10.1207/S15327965PLI1401_01

- McCrea, S. M., & Hirt, E. R. (2011). Limitations on the Substitutability of Self-Protection Processes: Self-Handicapping Is Not Reduced by Related-Domain Self-Affirmations. Social Psychology, 42, 9-18. http://dx.doi.org/10.1027/1864-9335/a000038

- Shepperd, J., & Arkin, R. M. (1989). Determinants of Self-Handicapping: Task Importance and Effects of Pre-Existing Handicaps on Self-Generated Handicaps. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 15, 101-112. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0146167289151010

- Siegel, P. A., Scillitoe, J., & Parks-Yancy, R. (2005). Reducing the Tendency to Self-Handicap: The Effect of Self-Affirmation. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 41, 589-597. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2004.11.004

- Steele, C. M. (1988). The Psychology of Self-Affirmation: Sustaining the Integrity of the Self. In L. Berkowitz (Ed.), Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, Vol. 21 (pp. 261-302). New York: Academic Press.

- Stone, J., & Cooper, J. (2001). A Self-Standards Model of Cognitive Dissonance. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 37, 228-243. http://dx.doi.org/10.1006/jesp.2000.1446

- Stone, J., & Cooper, J. (2003). The Effect of Self-Attribute Relevance on How Self-Esteem Moderates Attitude Change in Dissonance Processes. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 39, 508-515. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0022-1031(03)00018-0

- Stone, J., Wiegand, A. W., Cooper, J., & Aronson, E. (1997). When Exemplification Fails: Hypocrisy and the Motive for Self-Integrity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 72, 54-65. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.72.1.54

- Tesser, A., Crepaz, N., Collins, J. C., Cornell, D., & Beach, S. R. H. (2000). Confluence of Self-Esteem Regulation Mechanisms: On Integrating the Self-Zoo. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 26, 1476-1489. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/01461672002612003

NOTES

1In case that intelligence had been rated as the second most important dimension, the experimenter selected the personality dimension rated by the individual student as third in importance.

2Subsequent to the completion of the experiment, all participants were asked whether they had believed the cover story of the study and especially the negative test feedback. None of the subjects expressed serious doubts regarding the credibility of the cover story or the negative test feedback.

3In cases where intelligence had been rated as most important, participants wrote about the second most important personality dimension.