Low Carbon Economy

Vol.4 No.3(2013), Article ID:35433,9 pages DOI:10.4236/lce.2013.43010

Rural Housing Land Consolidation and Transformation of Rural Villages under the “Coordinating Urban and Rural Construction Land” Policy: A Case of Chengdu City, China

![]()

1College of Resources and Environment, Sichuan Agricultural University, Wenjiang, China; 2Key Laboratory of Land Information in Sichuan Province, Wenjiang, China; 3Land Planning and Cadastre Center of Chengdu, Chengdu, China.

Email: huangchun1985@126.com, *auh6@sicau.edu.cn

Copyright © 2013 Chun Huang et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Received June 5th, 2013; revised July 5th, 2013; accepted July 30th, 2013

Keywords: Rural Housing Land Consolidation; Rural Village; Resettled Farmers; China

ABSTRACT

The rapid urbanization and industrialization of China have led to a substantial reduction in farmland and the rapid expansion of urban-rural construction land, with the introduction of economic liberalization reforms in 1978. At present, scarcity of construction land for development has become the lead limiting factor in constraining economic growth. Rural housing land consolidation under the “coordinating urban and rural construction land” policy (CURCL) is an effective means of providing urban construction land for economic development, as well as controlling the amount of rural construction land. To better understand rural housing land consolidation in China, this paper, which takes Chengdu as a case study, has examined the implementation status. From this we conclude that although the rural housing land consolidation of Chengdu ostensibly changes only farmers’ place of residence, it actually involves changes in rural society, economy and organizational function. Through extensive interviews, this study indicates that although local governments are still the main body responsible for implementing rural housing land consolidation, external investment also plays an important role by improving the resettled farmers’ economic condition and promoting the transformation of their production modes and lifestyles to some extent.

1. Introduction

China has experienced fast-paced development and rapid urban growth in the three decades since Deng Xiaoping launched economic reforms in 1978. The demand for construction land is increasing rapidly, and the accompanying processes of industrialization and urbanization are occurring. However, because of China’s huge population and scant land resources per capita, there are sharp conflicts between population growth and land resource scarcity. Furthermore, current conflicts between construction land demand and agricultural land protection will only become more pronounced as growth continues [1]. Therefore land use planning to accommodate and reduce the impacts of industrial, commercial, and residential growth is critically important in China. This is because of the tension between pressure to provide land for economic growth and the imperative to preserve agricultural land [2].

The rapid urbanization of China has led to mass migration from rural to urban areas, with remarkable economic growth. Although the population of rural areas shows a decreasing trend, the amount of rural housing land shows an increasing trend [3,4]. For example, from 1996 to 2005, the population of rural areas decreased from 850.85 million to 745.44 million, with the proportion of rural population to gross population declining from 69.52% to 57.91% [5,6]. During the same period the total amount of rural housing land increased by approximately 64,600 ha, or about 0.71% [7]. At present, the average housing land area per household exceeds the normal m2/household rate. With massive rural-to-urban migration, a lot of old housing land is idle or abandonedand the amount of villages classifiable as “hollowed villages” is increasing throughout rural China. Conversely, the expansion of rural housing land is replacing farmland [8]. This is resulting in a serious waste of land resources, and aggravates the conflicts between urban construction land expansion and agricultural land protection.

To alleviate the conflicts between economic development and agricultural land protection, the Ministry of Land and Resources of China introduced a policy of coordinating urban and rural construction land (CURCL) in 2005. The key objective of the CURCL policy is to achieve equilibrium in the supply of land in China by balancing increases in urban construction land (driven by urbanization) with decreases in rural construction land1 (facilitated by out-migration) [4]. Farmers who participate in CURCL live in centralized residential districts organized through the rural housing land consolidation program, while still maintaining their rural identities. Former rural housing land can thus be reclaimed as farmland, and a percentage of newly-added farmland (reclamation area minus farmland area occupied by centralized residential district) can be converted into urban construction land to serve urban development needs [9]. As such, the CURCL policy is an instrument used by governments to provide construction land for economic growth as well as to protect arable land [2].

The primary objective of this study is to examine the implementation status of rural housing land consolidation. With the overall implementation of CURCL policy, it is imperative to understand that rural housing land consolidation is not a straightforward process, but is a comprehensive process involving changes in rural society, economy, and organizational function. More specific objectives of this study are to investigate the transformation of production modes and lifestyles of farming families who have been resettled through the rural housing land consolidation program. Understanding this not only potentially enhances the implementation of CURCL, but also facilitates building a more harmonious society.

This research is primarily a case study. Chengdu is selected as the study area, because it is one of China’s CURCL pilot areas. The transformation of rural society and economy through rural housing land consolidation that has occurred in Chengdu is sufficiently intensive to be a representative case. Conclusions drawn from this case-study of Chengdu may provide a good reference for other expanding cities, especially the western cities of China.

Data were collected through extensive interviews and personal observations. Relevant official documents were collected from Land Planning and Cadastre Center of Chengdu and were also used.

2. Rural Housing Land Consolidation in China

2.1. Review of Rural Housing Land Consolidation of China

Prior to 1978, growth of rural housing in China had been very slow. With the implementation of a market-based economy after 1978, many farmers have become increasingly affluent. Thus, multi-functional, more comfortable or more spacious houses have become more prevalent in rural areas [10]. Therefore, the total amount of rural housing land has been increasing sharply. Rural housing land consolidation, “building a new countryside” and developing a new way of ensuring sufficient farmland have become hot issues in current research given the background of the current of economic climate of intensive land-use [11].

Rural housing land consolidation includes two aspects: 1) decreasing the per capita area of housing land through the reclamation of old, idle and abandoned housing land; and 2) the economical use of land resources through merging small scattered villages into a central village. At present, there are three main calculation methods used to determine the potential of rural housing land consolidation in a given region: 1) the index method of per capita standard area of housing land; 2) the index method of per household standard area of housing land; and 3) the sampling survey method of idle housing land [12]. Several researchers have estimated the amount of newly-added farmland through rural housing land consolidation [13- 15]. Although the estimated results differed between calculation methods, there was a consensus that China had a very large potential for housing land consolidation in rural areas.

At present, the methods of implementing rural housing land consolidation are diverse. Based on difference in economic development level and the type of rural housing land between regions, there are three main construction types that can effectively decrease the amount of rural housing land: 1) the merger of small scattered villages; 2) rural housing land adjustment within a village; and 3) the relocation of a village [16,17]. Usually, management of rural housing land consolidation is government-oriented, and the means of funding include local government investment and market financing [18,19].

With the implementation of CURCL policy, rural housing land consolidation (as an important part of CURCL) has received extensive attention. Many studies of rural housing land consolidation in China demonstrate its benefits, with a number focusing on the economic and ecological benefits from a macroscopic angle [20-26].

2.2. Research Questions

A lot of research has concentrated on rural housing land consolidation of China, with studies focused on the mode of implementation and the economic and ecological benefits from a macroscopic angle. Under the theme of CURCL, rural housing land consolidation is considered as a means of providing urban construction land to serve urban development needs. Usually, rural housing land consolidation is implemented in rapidly developing regions. In this kind of region it is typical that urban economic, social, cultural and physical characteristics reach deep into rural areas, where they transform both the landscape and lifestyle [27].

Clearly, rural housing land consolidation in China also results in changes to rural lifestyles, because the first effect is a change in farmers’ place of residence. Whether this changes result in other alterations of villages from a microcosmic angle is less well documented. It is important, however, to determine whether these alterations influence resettled farmers’ productivity and wellbeing. Nonetheless, there has been little emphasis in analyzing rural housing land consolidation as a complex process that results in social, economic and functional changes in Chinese villages. As a result, there is a paucity of research that systematically examines how the production modes and lifestyles of the resettled farmers may have been affected by rural housing land consolidation. This study is an exploratory attempt to fill this research gap.

3. Rural Housing Land Consolidation under CURCL in Chengdu

According to the “The Policy of CURCL Pilot Project” issued by the Ministry of Land and Resources of China in 2005, the project area includes the reclamation area, the centralized residential district, and newly-added urban construction land. One of the parameters of the project was that the farmland area occupied by the centralized residential district and newly-added urban construction land must be smaller than the reclamation area.

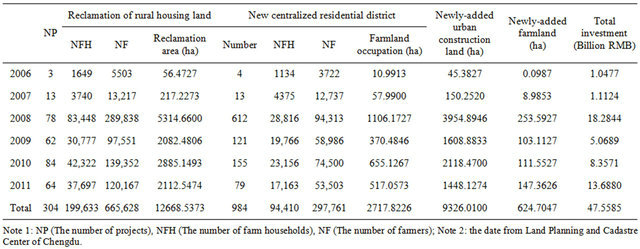

In 2006, per capita housing floor area is more than 155 m2 in the rural area of Chengdu, which exceeds the maximum of per capita housing floor area (70 m2) in accordance with “Technical Guide for New Socialist Countryside Construction in Chengdu”. Therefore, rural housing land has great consolidation potential in Chengdu. Table 1 shows the implementation of the consolidation projects of rural housing land under CURCL in Chengdu from 2006 to 2011. It shows that between 2006 and 2007, reclamation area and newly-added urban construction land throughout 16 project sites were 273.7000 ha and 195.6347 ha, respectively, and the numbers of farming households and farmers involved in these projects were 5389 and 18,720, respectively. From 2007 onwards, reclamation area and newly-added urban construction land through 288 projects were 12394.8373 ha and 9130.3753 ha, respectively. The numbers of farming households and farmers involved in these projects were 194,244 and 646,908, respectively. This increasing trend reflects the consensus that consolidation projects of rural housing land were of great assistance to urban development, and thus local governments have become increasingly involved in projects of this kind.

During the 2006-2011 period, 984 centralized residential districts were constructed to accommodate the resettled farmers whose housing land had been reclaimed as farmland (Table 1). As Table 1 shows, the numbers of farming households and farmers involved in all projects were far greater than those in centralized residential districts (from 199,633 to 94,410 and 665,628 to 297,761, respectively). The reason for this phenomenon is that a lot of farmers involved in all projects choose monetary resettlement, either because they had two or more houses or because they became rural-to-urban migrants and now live permanently in urban areas. A curious phenomenon in these tables is that in 13 projects the number of farming households involved was fewer than the number of households in centralized residential districts in 2007 (from 3740 to 4375). This rise is the result of household partition. Under “Land Management Law” Article 62, when farmers’ children who are of agricultural registration status (nongcunhukou) marry, they can construct a new house for their children, and thus the number of households increases. In the implementation process of rural housing land consolidation, some farmers make full use of this policy to divide their households, thus they can receive two (or more) resettlement houses.

At present, scarcity of construction land for development has become a limitation on sustained economic growth, and a significant issue for local communities [28]. The CURCL policy immediately presented an effective means of breaking the bottleneck of land constraints, and was welcomed by local governments [2]. In Chengdu, there was a large-scale consolidation of rural housing land under CURCL, which involved a large number of farmers, land and investment (including reclamation fees and resettlement fees). From these figures, it is clear that rural housing land consolidation has had a great influence on rural society and economy.

4. Transformation of Socio-Economic Characteristics of Rural Villages

Because urban development is such a pressing need in China, many local governments have implemented consolidation projects of rural housing land under CURCL. Inevitably, this has resulted in changes to resettled farmers’

Table 1. The implementation of the consolidation projects of rural housing land under CURCL in Chengdu from 2006 to 2011.

physical, social, economic and cultural lifestyles.

4.1. Farming Radius

Chinese farmers have traditionally chosen a site for their farmhouse close to their farmland [29]. Rural housing land consolidation changes farmers’ place of residence. Thus, to minimize disruption to farmers’ livelihoods, the site selection process of centralized residential districts should take the distance from the planned settlement to the planned inhabitants farms (hereafter referred to as farming radius) into consideration. In Chengdu, the usual maximum farming radius for a settlement is 2 km [30]. Thus, for some resettled farmers the distance from their homes to their farms has presented a new daily inconvenience. For example, in Xingfu village, a typical project area of rural housing land consolidation in Wenjiang City in Chengdu, more than 50% of farm households have participated in the rural housing land consolidation program. More than one-third of resettled farmers spent more time walking to their farmland than previously, and some farmers even need to take the rural bus to their farmland (according to Mr. Song, the director of the Wenjiang village committee [personal interview in Chinese, April 10, 2012]).

The increase in farming radius inevitably increases agricultural production time [31]. To gain extra income or satisfy their livelihood needs, most farmers grow vegetables and raise livestock. For this kind of farm work it is necessary to walk from the farmhouse to the farmland every day or every few days. We therefore found in our interviews that the increase of farming radius was regarded as the most burdensome of agricultural production activities for most farmers following rural housing land consolidation.

4.2. Production Mode

Through rural housing land consolidation, a large number of old, idle and abandoned farmhouses have been reclaimed as farmland. Obviously, rural housing land consolidation reduces farmland fragmentation based on distribution characteristics of rural housing land, and creates favorable conditions for agricultural scale management [32]. In general, local governments introduce one or more agricultural industrialization enterprises after rural housing land consolidation has been carried out. This is because the capital, technology and management of agricultural industrialization enterprises are beneficial for improving agricultural productivity.

Commercial enterprise participation in agricultural production has brought about enormous social and economic changes in consolidation areas. For example, enterprises rent a large tract of farmland from farmers on which they implement broad-scale agricultural management, and employ a percentage of these farmers to work on the newly consolidated farm. In Shengjian and Qunan villages, two typical project areas of rural housing land consolidation in Chongzhou City in Chengdu, more than 70% of resettled households rent their farmland to agricultural industrialization enterprises. The area of rented farmland per household ranges from 0.0667 ha (1 mu) to 0.2667 ha (4 mu), with an average yearly rent of RMB 12000 per ha (RMB 800 per mu). In Shengjian village, about 30% of the rural residents do not make a living by agricultural production, about 30% are employed by these enterprises during the busy farming season with an average daily wage of RMB 50 per person, about 30% have migrated to urban areas, and the remainder (mainly the elderly) do not engage in physical labor (according to Mr. Yang, the director of the Shengjian village committee [personal interview in Chinese, April 11, 2012]). In Qunan village in 2010, an enterprise set up processing factories of agricultural products in a centralized residential district. Now (2012) more than 200 resettled farmers are employed in non-agricultural jobs by these factories, with an average monthly salary of RMB 1000 per person (according to Mr. Hu, the deputy party secretary of the Qunan village committee [personal interview in Chinese, April 12, 2012]).

Thus, the traditional production mode of resettled farmers has been changed by these introduced commercial enterprises as well as through rural housing land consolidation. Frequently the salaries from these enterprises have become an important source of income for resettled households in consolidation areas.

4.3. Centralized Residential Districts

In the implementation process of rural housing land consolidation under CURCL, local governments are required to build new centralized residential districts to resettle farm households which chose to participate in the program. According to our interviews, each farm household receives a resettled two or three story house free of charge, with the per capita floor area of 35 m2 (Figure 1).

Not only are electricity and tap water available in all districts, but in largeand medium-scale districts natural gas is also available. Apart from this infrastructure, there are also small supermarkets, teahouses, restaurants and medical stations in largeand medium-scale districts. Local governments have also adopted some measures to upgrade rural districts, such as setting up garbage collection stations and garbage bins. In addition, many public facilities such as basketball courts, culture rooms and activity rooms for the elderly have been built within largeand medium-scale districts. Largeand mediumscale centralized residential districts are therefore significantly different from scattered residential areas. To some extent, these rural resettlement districts are like urban communities.

4.4. Transformation of Daily Living Habits

Some daily living habits of the resettled farmers have changed with the change of their living environment. The most prominent example is non-agricultural work. As described above, a percentage of resettled farmers have rented their farmland to agricultural industrialization enterprises, and have then taken up various types of nonagricultural work in surrounding areas, especially in the slack farming season. The transition from farming to non-farming occupations causes these rural dwellers to abandon farming-related traditions and adopt new and

Figure 1. The new centralized residential district in Xingfu village of Wenjiang District, Chengdu.

urban lifestyles parallel with non-farming work [33].

Many of the resettled farmers have also changed their leisure activities. For example, many resettled farmers choose to take a walk in their districts or along the rural roads connecting districts to towns after supper in the summer, instead of watching TV at their own home or drinking tea in their farmhouses’ front threshing ground as they did when residing in scattered residential areas. There are also many resettled farmers who go dancing (babawu) in their district’s square after supper (Figure 2). In addition, farmers who have transitioned to non-agricultural jobs have more free time than before, and may participate in different leisure activities in their off-duty time, such as playing mah-jong.

4.5. Organizational Function of Village Committees

According to the “Organic Law of Villagers Committees”, village committees are the basic administrative unit. Before rural housing land consolidation, village committees were mainly responsible for publicizing the state’s directives and policies, providing management and service for agricultural production and handling daily disputes among villagers.

In general, some follow-up construction projects are carried out after rural housing land consolidation, such as farmland consolidation projects, agricultural improvement projects and farmland water conservation projects. In addition, with the change of living environment the resettled farmers have a higher demand for cultural life than before resettlement. Thus, the main functions of village committees have also changed through rural housing land consolidation. Post-resettlement village committees put emphasis on providing public services and assisting higher level governments in implementing various types

Figure 2. The resettled farmers dancing (babawu) in their district’s square after supper.

of construction projects.

5. Discussion

The CURCL policy is a distinctively Chinese policy solution that reflects the unique hybrid nature of the Chinese political-economy: where economic liberalization is combined with a strong state [4]. Rural housing land consolidation, as an important part of CURCL projects, has attracted increasing attention. It differs from rural land requisition in that resettled farmers maintain their rural identities (nongcunhukou), and still have their farmland. Thus, rural housing land consolidation is generally understood as a change of farmers’ residence. However, it also involves the transformation of the resettled farmers’ lifestyles, production modes and the organizational function of village committees.

The implementation of rural housing land consolidation generally relies on external investment to relieve the financial pressure of local government and accelerate construction progress [34,35]. In Chengdu between 2006 and 2011, more than forty percent of investment (19.4199 billion RMB) came from external investment. And the ratio of external investment to total investment during this period also showed an increasing trend. According to the “The Management Measures of CURCL Pilot Project”, to prevent the unchecked expansion of large cities, there is a strict policy that the quota of newly-added urban construction land is only used at the county scale. Therefore, investment companies make their profit through making the quota of newly-added urban construction land over to the local governments, which will publicly auction the quota to commercial enterprises that urgently need construction land to develop.

In the implementation process of rural housing land consolidation, the site selection of centralized residential district is key. The three main principles guiding it are: 1) the site must not be in a geological hazard area; 2) the site cannot occupy prime farmland; and 3) there is a reasonable farming radius. Determining a reasonable farming radius depends on factors including landforms, agricultural production technology and equipment, labor quality, and agricultural structure. Thus, the reasonable farming radii are different in different regions [29,36-38]. We found in our interviews that the resettled farmers who no longer make their livings by agricultural production or who had a wide farming radius after resettlement are more supportive of the program than others. Several other studies support this conclusion [39,40].

Largeand medium-scale centralized residential districts reflect the full transformation of rural society and economy after rural housing land consolidation. The farmers of these districts simultaneously possess rural and urban characteristics. This is largely because of the fact that 1) they maintain their rural identities (nongcunhukou) and still have their farmland; and 2) like urban residents they enjoy a range of public services and conveniences, such as small supermarkets, medical services and fitness facilities. Additionally, most of them also engage in non-agricultural jobs, which result in their lifestyles differing from traditional rural life.

After rural housing land consolidation, there are usually three means of commercial enterprise participation in China. The first is that agricultural industrialization enterprises provide free seeds, chemical fertilizers, pesticides and cultivation technologies for resettled farmers, who grow vegetables or other cash crops in accordance with the enterprise’s requirements. Farmers must then sell agricultural products to the enterprise according to the prices that are agreed by the enterprise and farmers before planting crops. The second is when enterprises rent a large tract of farmland from resettled farmers, develop it with broad-scale agricultural management techniques, and employ a percentage of these farmers to engage in agricultural production activities. The third means by which enterprises participate is by setting up processing workshops for agricultural products in a centralized residential district. This provides non-agricultural employment for resettled farmers. Accordingly, it can be seen that the traditional production modes and lifestyles of resettled farmers have been changed to some extent by enterprises introduced following rural housing land consolidation.

In addition, not all farmers are willing to participate in rural housing land consolidation. According to the requirements of the Ministry of Land and Resources of China, farmhouses cannot be demolished in the implementation process of CURCL without farmers’ consent. However, it is recognized that some local governments do forcefully implement large-scale consolidation of rural housing land to sustain or accelerate economic growth, even though some of these farmers are not willing to move. When the farmers’ interest cannot be effectively guaranteed, compulsory implementation of rural housing land consolidation inevitably leads to conflict between these farmers and local governments. For example, the farmers responded with violence during the demolition of villages in some cities of Shandong Province, where they were required to make up the value differences between their houses and the new apartments in which they were resettled to local governments [41]. This is a disharmonious and undesirable phenomenon, and thus to support harmonious social development in China, farmers’ wishes must be respected throughout the process of development.

6. Conclusions

The introduction of economic liberalization reforms in 1978 has resulted in the rapid urbanization and industrialization of China, which in turn has led to a substantial reduction in farmland and the rapid expansion of urban-rural construction land. At present, there is a conflict between urban construction land expansion and arable land protection. Rural housing land consolidation under CURCL is an effective means of providing urban construction land for economic development, as well as controlling the amount of rural construction land. To better understand rural housing land consolidation in China, this paper, which takes Chengdu as a case study, has examined the implementation process. From this we conclude that although the rural housing land consolidation of Chengdu ostensibly changes only farmers’ place of residence, it actually involves changes to rural society, economy and organizational function.

Through extensive interviews, this study indicates that although local governments are still the main body responsible for implementing rural housing land consolidation, external investment also plays an important role. In the implementation process of rural housing land consolidation, investment companies can effectively relieve the financial pressure of local governments and accelerate the construction progress. After rural housing land consolidation, agricultural industrialization enterprises can improve the resettled farmers’ economic condition, and promote the transformation of their production modes and lifestyles to some extent.

Future research needs to be focused on investigating and analyzing the long-term effect of rural housing land consolidation on rural society and economy. It can also be conducted to integrate the spatial analysis into the changes to the resettled farmers’ production modes and lifestyles after rural housing land consolidation.

7. Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful for funding of this research under the grants from China National Key Technology R&D Program (NC2010RE0057) and Special Fund for Scientific Research in the Public Interest of the Ministry of Land and Resources of China (201211050-09).

REFERENCES

- H. L. Long, “Rural Housing Land Transition in China: Theory and Verification,” Acta Geographica Sinica, No. 10, 2006, pp. 1093-1100.

- Y. Tang, R. J. Mason and P. Sun, “Interest Distribution in the Process of Coordination of Urban and Rural Construction Land in China,” Habitat International, Vol. 36, No. 3, 2012, pp. 388-395. doi:10.1016/j.habitatint.2011.12.022

- H. L. Long and T. T. Li, “The Coupling Characteristics and Mechanism of Farmland and Rural Housing Land Transition in China,” Journal of Geographical Sciences, Vol. 22, No. 3, 2012, pp. 548-562. doi:10.1007/s11442-012-0946-x

- H. L. Long, Y. Li, Y. Liu, M. Woods and J. Zou, “Accelerated Restructuring in Rural China Fueled by ‘Increasing vs. Decreasing Balance’ Policy for Dealing with Hollowed Villages,” Land Use Policy, Vol. 29, No. 1, 2012, pp. 11-22. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2011.04.003

- National Bureau of Statistics of China, “China Statistical Yearbook,” China Statistics Press, Beijing, 1997.

- National Bureau of Statistics of China, “China Statistical Yearbook,” China Statistics Press, Beijing, 2006.

- W. Song, B. M. Chen, H. Yang and X. W. Chen, “Analysis on the Status Quo of Residence Base Resources in Rural Areas of China,” Chinese Journal of Agricultural Resources and Regional Planning, Vol. 29, No. 3, 2008, pp. 1-5.

- Q. H. Huang, M. C. Li, Z. J. Chen and F. X. Li, “Land Consolidation: An Approach for Sustainable Development in Rural China,” Ambio, Vol. 40, No. 1, 2011, pp. 93-95. doi:10.1007/s13280-010-0087-3

- Y. Tang, X. J. Tan and J. Q. Zhang, “Summary of Study on Coordination and Interaction of Urban and Rural Construction Land Use,” Journal of Northwest A & F University (Social Science Edition), Vol. 11, No. 5, 2011, pp. 75-79.

- H. L. Long, G. K. Heilig, X. B. Li and M. Zhang, “SocioEconomic Development and Land-Use Change: Analysis of Rural Housing Land Transition in the Transect of the Yangtse River, China,” Land Use Policy, Vol. 24, No. 1, 2007, pp. 141-153. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2005.11.003

- Y. Liu, C. F. Wu and Z. R. Yang, “Review and the Outlook of Residential Area Consolidation in Rural China,” China Land Science, Vol. 22, No. 3, 2008, pp. 68-73.

- W. Song, B. M. Chen and G. H. Jiang, “Research on Land Consolidation Potential of Rural Habitat in China: Review and Preview,” Economic Geography, Vol. 30, No. 11, 2010, pp. 1871-1877.

- X. Y. Li, J. L. Zhang, W. Y. Zheng, C. J. Tang, Z. Miao and K. Liu, “Calculation and Analysis of Land Consolidation Potential in Rural Habitat during Rapid Urbanization Process in China,” Transactions of the CSAE, Vol. 20, No. 4, 2004, pp. 276-279.

- X. S. Lu, “National General Land Use Planning in China,” China Land Press, Beijing, 2006.

- Y. M. Ye and C. F. Wu, “The Potentiality, Operation Modes and Strategic Policy Choice of Rural Housing Land Consolidation,” Problems of Agricultural Economy, No. 10, 1998, pp. 54-57.

- Y. Gao and Y. M. Ye, “Influential Factors Analysis and Mode Selection of Rural Residential Land Consolidation,” Rural Economy, No. 3, 2004, pp. 23-25.

- J. Li and J. K. Wang, “Rural Homestead Finishing and the Model Analysis,” Chinese Countryside Well-Off Technology, No. 10, 2009, pp. 19-21.

- Q. Y. Yang, Y. Z. Tian, C. Y. Wang, T. Zhou and X. J. Liu, “On the Land Use Characteristics and the Land Consolidation Models of Rural Residential Area of the Hilly and Mountainous Regions in Southwest China: A Case of Chongqing,” Geographical Research, Vol. 23, No. 4, 2004, pp. 469-478.

- Q. Y. Yang and Z. L. Zhang, “A Study on the Target and Patterns of the Residential Area Land Consolidation in Metropolitan Outskirt—A Case of Shunyi District,” China Soft Science, No. 6, 2003, pp. 115-119.

- Y. Y. Chen, Q. J. Zhang and D. L. Lu, “Real Potential Estimate and Benefit Evaluation of Rural Settlement Consolidation—As an Example to Jiaxiang County,” Journal of Hebei Normal University (Natural Science Edition), Vol. 34, No. 2, 2010, pp. 231-236.

- L. P. Ding, X. L. Hao, Q. L. Song and B. Gui, “Potentiality Analysis and Benefit Evaluation of Rural Residential Land Consolidation in Suining City of Jiangsu Province,” Shandong Land and Resources, Vol. 27, No. 7, 2011, pp. 45-48.

- J. L. Dou, J. L. Zhang, F. R. Zhang, N. Wang, H. Yang and J. Lu, “Ecological Effect Evaluation of Rural Residential Area Improvement,” Natural Resource Economics of China, No. 5, 2008, pp. 38-40.

- Y. G. Li, “Study on Rural Residential Land Consolidation under the Background of Urban and Rural Harmonious Development,” Journal of Hebei Agricultural Sciences, Vol. 14, No. 4, 2010, pp. 106-108.

- D. Liu and Y. Chen, “On Readjustment Mode and Its Benefit of Farmers’ Resident Land-Use—In the Perspective of the Farmers and Investigation of Jiangxi Province,” Journal of Hunan Agricultural University (Social Sciences), Vol. 10, No. 6, 2009, pp. 43-46.

- Y. B. Wang, G. P. Lei, Y. Tang and J. Wang, “Discussion about Efficiency Evaluation Method of Land Consolidation on Resident Spots for Rural Denizens,” Chinese Journal of Agricultural Resources and Regional Planning, Vol. 29, No. 2, 2008, pp. 39-43.

- K. Wang, D. T. Xie, C. F. Huang and S. Wang, “Hook Benefit Evaluation on the Increase of Urban Construction Land and the Decrease of Rural Construction Land in the Suburbs of Chongqing City, China,” Journal of Anhui Agricultural Science, Vol. 39, No. 18, 2011, pp. 11192- 11194.

- J. Friedmann, “Four Theses in the Study of China’s Urbanization,” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, Vol. 30, No. 2, 2006, pp. 440-451. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2427.2006.00671.x

- M. W. Skinner, R. G. Kuhn and A. E. Joseph, “Agriculture Land Protection in China: A Case Study of Local Governance in Zhejiang Province,” Land Use Policy, Vol. 18, No. 4, 2001, pp. 329-340. doi:10.1016/S0264-8377(01)00026-6

- K. Zhao and Z. J. Hui, “Research of Rural Suitable Farming Radius in North Shanxi Yellow Soil Inter-Vale Area,” Shanxi Architecture, Vol. 34, No. 8, 2008, pp. 14-16.

- X. L. Wu, “The Experience and Inspiration of Linking the Increase and Decrease of the Land for Construction Use in Both Urban and Rural Areas in Chengdu City,” Soft Science, Vol. 25, No. 5, 2011, pp. 99-101.

- S. H. Tan, “The Effects of Current Farmland Management Patterns on Agricultural Production Cost,” Journal of Agro-Technical Economics, No. 4, 2011, pp. 71-77.

- X. Lv, X. J. Huang, T. Y. Zhong and Y. T. Zhao, “Review on the Research of Farmland Fragmentation in China,” Journal of Natural Resources, Vol. 26, No. 3, 2011, pp. 530-540.

- Y. Xu, B. Tang and E. H. W. Chan, “State-Led Land Requisition and Transformation of Rural Villages in Transitional China,” Habitat International, Vol. 35, No. 1, 2011, pp. 57-65. doi:10.1016/j.habitatint.2010.03.002

- Y. Hou, H. Q. Jin and G. Y. Wang, “Survey and Thoughts on Village Transformation Experiment in Heze City,” Shandong Land and Resources, Vol. 26, No. 4, 2010, pp. 39-42.

- H. R. Yang and Z. L. Shi, “Study on Decreasing Construction Using Land in Urban Area and Increasing Agricultural Land in Rural Area in Cangshan County,” Shandong Land and Resources, Vol. 27, No. 7, 2011, pp. 42- 44.

- G. R. Hong, “Study on Feasibility of Residential Clustering Construction in Rural Areas,” Journal of Anhui Agricultural Sciences, Vol. 38, No. 3, 2010, pp. 1568-1569.

- X. Shen, “Survey of Village Construction and Development in Jiangsu Province,” City Planning Review, Vol. 30, No. 8, 2006, pp. 56-60.

- J. N. Zhang, N. Ji, Y. C. Chen and J. B. Ni, “Selective Methods and Their Application of Basic-Level Village in Country Planning: Research under the Policy of ‘Pothook of City Construction Land Increase and Rural Residential Land Decrease’,” South Architecture, No. 4, 2009, pp. 32- 35.

- Y. Chen, Y. R. Chen and W. B. Ma, “Intention of Land Circulation in Reservoirs Resettlements Based on the Logistic Model: An Investigation into Sichuan, Hunan and Hubei Provinces,” Resources Science, Vol. 33, No. 6, 2011, pp. 1178-1185.

- Y. Q. Wang and L. G. Chen, “The Effect of Farmers’ Concentration Living on Land Fragmentation,” Rural Economy, No. 10, 2008, pp. 6-9.

- X. Y. Song and H. Yan, “Several Provinces Force Withdrawal of Village Land for Construction to Expand the Land in Exchange for Financial Benefits,” The Beijing News, No. 11, 2010, pp. A16-A17.

NOTES

*Corresponding author.

1In this article the term “rural construction land” is used synonymously with “rural housing land” (zhaijidi) that includes housing land and threshing ground.