Advances in Literary Study

Vol.04 No.03(2016), Article ID:67777,4 pages

10.4236/als.2016.43006

A Cultural Examination of Shapiro’s Translation of the Marsh Heroes’ Nicknames

Yanli Bai

Inner Mongolia University, Huhhot, China

Copyright © 2016 by author and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received 9 May 2016; accepted 25 June 2016; published 28 June 2016

ABSTRACT

What roles the culture plays in translating has been a focus in the translating circle. The stratificational relation of language to cultural context in Systemic Functional Linguistics (SFL) makes it necessary that the process of translation should take the cultural factors into consideration. The present paper aims to discuss the parts that culture plays in translating by analyzing some problems in Shapiro’s translation of the nicknames in the Outlaws of the Marsh. The paper starts off from the relation of language to culture context in translation in an SFL angle, followed with a brief introduction to the connotation and the artistic magic of the Marsh Heroes’ Nicknames and some examples of Shapiro’s translations of the nicknames, in order to demonstrate the importance of culture factors in translating.

Keywords:

The Outlaws of the Marsh, Nicknames, Translation, Culture

1. The Systemic Functional Relation of Language to Culture in Translation

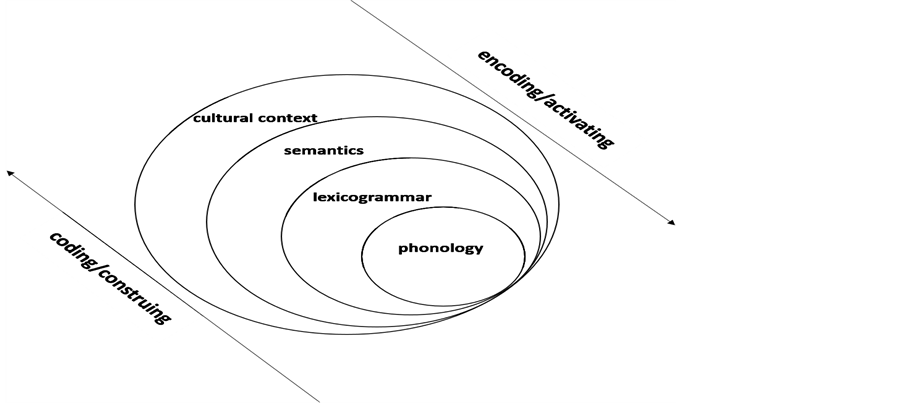

Nida (1998) points out that neither language nor culture can exist independent of each other, with the latter not only representing but also modeling the elements of the latter; and that the faster changing of culture than that of language makes it vital that the meaning of a word should be determined by both the syntagmatic contexts and the cultural contexts. In the view of Systemic Functional Linguistics, language can be theoretically divided into at least three strata (levels): semantics (meaning), lexicogrammar (wording) and phonology (sounding) and if the context is considered, together they form a four-stratumed model of abstraction, and the context being above the semantics. The relationship among these strata―the process of linking one level of organization with another―is realization: context is realized by semantics, and the realization of the semantics is realized by the realization of the lexicogrammar in phonology ( Halliday & Matthiessen, 2004, 2014 ). Hasan (2010) puts this relation in another way: from below to above (namely from phonology to context) it, the relation of construing or encoding, with phonology coding or construing the lexicogrammar, lexicogrammar coding or construing semantic and semantics coding or construing context; and the other way round, it is the relation of encoding or activating, with the stratum above encoding or activating the one below. Since context is subsumed into situation context and cultural context, we can say that cultural context is coded or construed by the construing or the coding of the semantics by the lexiogrammar (see Figure 1).

Therefore, as a cross-cultural as well as a cross-language activity, translation cannot ignore the cultural considerations. As Wang (2014) puts it, “to a certain extent, literary and cultural translation is a form of (cross) cultural interpretation, by means of which some excellent literary works of rich cultural connotation will have a continued life or ‘afterlife’ in another language and cultural environment”. On the basis of the importance of the relationship between language and culture, the present paper will make an examination of the English translation of the Marsh heroes’ nicknames by Shapiro in light of the Chinese culture carried by the names.

2. The Connotation and the Artistic Magic of the Marsh Heroes’ Nicknames

Under the authorship of Shi Nai’an and Luo Guanzhong, the Outlaws of the Marsh starts a tradition of adopting nicknames to address the characters in the novels of chivalry and heroism, whereby their looks, martial arts, origins, intelligence, skills, personalities, etc. can be vividly marked. The Outlaws of the Marsh features one hundred and eight heroes and heroines who come from various levels of society. Each of them is undoubtedly the ideal of the hero to the heart of the Chinese people. In terms of the source of nicknames, some generalize the heroes’ appearance and personalities, such as the Panther Head (Lin Chong), the Thunderbolt (Qin Ming); some describe the heroes’ martial arts or skills such as the Magic Calculator (Jiang Jing), and the Fire General (Wei Dingguo). As far as the art of language is concerned, some nicknames sound rather harsh and cruel such as the Black Whirlwind (Li Kui); some quite elegant and liberal such as the Single Blossom (Cai Qing); some demoniac such as the One Who Heads Not His Life (Shi Xiu); some cool and indifferent such as Hell’s Summoner (Li Li). Thus when the reader read the Black Whirlwind in the novel, he or she will not only associate it with Li Kui himself, but also with what personality he is: loyal, straightforward, rash and killing without thinking etc. Therefore, nicknames can provide the reader with a vivid and lively image of the character.

The marsh heroes’ nicknames reflect the author’s cultural option and aesthetic conception as well as the psychological need and moral trend of the public in a certain period of history ( Yang, 1982 ). In the Outlaws of the Marsh, the introduction of a hero is typically in the order of his name followed by his nickname. As mentioned above, each nickname is the generalization of a hero’s outstanding feature. In the novel, nicknames are more often used and, in most cases, enjoy a higher reputation than their real names. Therefore, nicknames have become a powerful symbol of the heroes’ status. Since the authors of the work lived in the feudal society and their novel describes the peasants’ strike against feudal rule, the heroes’ nicknames in the novel inevitably bear the brand of

Figure 1. The stratificational relation of language to cultural context.

the times. A case in point is Song Jiang whose nickname is the Timely Rain. He is so called because he is always ready to help and save those in need. Another is Shi Xiu nicknamed The -one-who-heads-regardless-of- his-own-life who is straightforward by nature and cannot tolerate any injustice and would go great strength to protect the wronged party. This reflects, to a large extent, a positive feudal concept of attaching more importance to the justice than to the wealth.

In light of this, a reader’s ignorance of Chinese culture in a certain time will definitely lead to his failure to comprehend the nicknames in the novel. Take, for example, Wu Song who is also called the Tiger-killing Hero. In the Chinese culture, a tiger is regarded as the king of all beings (That is why many nicknames have “tiger” in them, e.g. The Elegant Tiger). In ancient times, if anyone could kill a tiger barehanded, he will undoubtedly be admired as a real hero1. Another example is about dragon, which, as a mythological animal, has been admired to extreme by Chinese people who even think of themselves as its descendants. The term “dragon” symbolizes intelligence, bravery, power and fortune. No wonder seven heroes of the Marsh are nicknamed with “dragon”. As far as translation is concerned, what a translator has to take into considerations involves not only the cross- wordings between the two languages but also the cross-elements between the cultures respectively carried by the two languages.

The cultures across the world are bound to be different from each other because they belong to different peoples who live in different natural and geographical environments with different history, different economic conditions and different political systems. Besides, their religious beliefs, moral standards, the rules of behaviors and the ways of living are quite different. The Chinese nation, with a history of more than five thousand years, has a glorious civilization, in which Chinese language has been playing a vital role in recording the culture and its tradition. As a classic, the Outlaws of the Marsh employs a lively and graphic language to nickname each hero. Nicknames derived from among the people and, after years of accumulation and improvement, they have recorded culture, custom and tradition of the people.

The nicknames in the Outlaws of the Marsh have distinctive characteristics of Chinese national culture. Therefore, it is not easy to translate them into English. Translating itself is a cross-cultural activity. The greatest obstacle a translator is always encountered with is the difference of the two cultures as well as that of the languages. Therefore, if a translator wants to transfer sufficient information to his target readers, he has to take into account the factors of both the culture and the language he is dealing with.

3. Comments on Sidney Shapiro’s Translation of the Marsh Heroes’ Nicknames

On balance, Shapiro’s translation of the Outlaws of the Marsh is loyal to the original work. His version can convey to western readers the literal meaning, connotation and the implication of the novel. From cross-cultural point of view, Shapiro’s translation of the nicknames succeeds in passing on the basic cultural information to the reader. Therefore, Shapiro has made a great contribution to the publicization of Chinese culture. For example, a western reader can clearly feel how much a dragon and a tiger mean to Chinese people. And it will come to the reader that there must be legends and myths beyond such nicknames as the Lesser Li Guang, the Second Rengui, the Nine-tailed Tortoise and Eight-armed Nezha, etc.

Yet, not all Shapiro’s translations of the nicknames are perfect. There are still some to be bettered. The following three groups are about the problems of Shapiro’s translations of the nicknames.

3.1. Mistranslations Due to the Translator’s Misunderstanding of the Cultural Information of the Nicknames

In Shapiro’s version, some mistakes could be found in his translation of some mistakes due to his ignorance of the cultural information about the nicknames.

Example 1. Zhang Heng (the Boat Flame). Here Zhang Heng’s (张横) nickname is Chuan Huo Er (船火儿). In Song Dynasty, “huo’er” is not simply fire or flame. It refers to a “boatman”. Therefore, the Boat Flame is a mistranslation. “The Boatman” could be a better replacement.

Example 2. Shi Xiu (the Rash). Shi Xiu’s (石秀) Chinese nickname is “pin ming san lang” (拼命三郎) “Rash” means “acting or done without careful consideration of the possible consequences”2 But in the Outlaws of the Marsh “pin ming ”means fighting to death which just fits Shi Xiu’s character who is straightforward and brave and ready to fight till death to protect the justice. So “rash” is a wrong translation here. In addition, the translator ignores “san Lang” (三郎) which means the third among brothers in a family in Song and Yuan Dynasties. Therefore, the translator cannot convey correct and sufficient information to the reader in his translation.

3.2. Insufficient Translations of Some Nicknames

Some translations of the nicknames don not contain all the information that the original names have, which is bound to affect the reader’s comprehension and appreciation of the novel.

Example 3. Dai Zong (神行太保) (the Marvelous Traveler). In fact, “tai bao” (太保) has many meanings. Perhaps it is beyond Shapiro’s ability to determine which meaning exactly is suitable here, so he leaves it out. In Song and Yuan Dynasties, “tai bao” refers to a wizard. Dai Zong (戴宗) is called “shen xing tai bao” because he has the magic of a wizard, which enables him to travel 800 li a day. Therefore “the Marvelous Traveler” seems too simple here.

Example 4. An Daoquan (the Skilled Doctor). Here the Skilled Doctor is not enough to express “shen yi”(神医). “The Highly-skilled Doctor” or “the Miracle-working Doctor” will be better.

Example 5. Shan Yan’gui (The Water General) and Wei Dingguo (the Fire General). The former is “sheng shui jiang” (圣水将) in Chinese, and the latter is “sheng huo jiang” (圣火将) in Chinese. Here the omission of “sheng” (圣) makes the translations less interesting than the originals and the reader cannot fully comprehend the characters.

3.3. Misapplications of Some Substitutes Which Is Not Suitable in Cross-Cultural Communications

In the quest of simplicity and easy understanding, the translator means to apply some words which do not match with Chinese culture.

Example 6. Lu Junyi (the Jade Unicorn). A kylin (麒麟) is quite different from a unicorn(独角兽) in that the former is a benevolent animal in the ancient China’s mythology, which resembles a deer in shape with one corn and a tail like a cow’s, and with fish scales all over its body, while the latter is “a mythical animal generally depicted with the body and head of a horse, the hind legs of a stag, the tail of a lion, and a single horn in the middle of the forehead ”3. Therefore, “unicorn” as the equivalence of “kylin” will blind the reader to the fact that the two animals are different and from different cultural mythologies. “The Jade Kylin” will be better.

Example 7. Wu Song (the Pilgrim). Here “pilgrim” is a typical English term which should not be used to translate “xing zhe”(行者).

4. Conclusion

The coding and encoding relationship between language and culture context makes it necessary and vital that the process of translation should take into account the cultural information of the source language. The nicknames in the Outlaws of the Marsh are created by Chinese people who are rooted in the Chinese culture and tradition. Thus, the nicknames have the characteristics of Chinese nationality. Therefore, it is far from enough for a translator to merely know the literal meaning of the nicknames. He/she has to know well about their origins and development and, the most important, the culture behind them before translating them into English.

Cite this paper

Yanli Bai, (2016) A Cultural Examination of Shapiro’s Translation of the Marsh Heroes’ Nicknames. Advances in Literary Study,04,33-36. doi: 10.4236/als.2016.43006

References

- 1. Halliday, M. A. K., & Matthiessen, C. M. I. (2004). An Introduction to Functional Grammar. London: Routledge.

- 2. Halliday, M. A. K., & Matthiessen, C. M. I. (2014). An Introduction to Functional Grammar. London: Routledge.

- 3. Nida, E. (1998). Language, Culture and Translation. Journal of Foreign Languages, 3, 29-33.

- 4. Wang, N. (2014). Translation and Cross-Cultural Interpretation. Chinese Translators Journal, 2, 2-14.

- 5. Yang, S. H. (1982). On the Aesthetic Meaning of the Nicknames of the Figures in Outlaws of the Marsh. Journal of Huazhong Normal University ( Humanities and Social Sciences), 4, 135-138.

NOTES

1But things are quite different now, since tigers have been specially protected. So anyone who kills or injures a tiger will not become a hero but a criminal.

2Oxford Advanced Learner’s English-Chinese Dictionary, the Commercial Press, 1997, P1232.

3 Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary, 2005.