American Journal of Industrial and Business Management

Vol.06 No.01(2016), Article ID:62898,23 pages

10.4236/ajibm.2016.61001

Measuring the Effects of Corporate Tax on Corporate Income: The Role of Corporate Income Tax Incentives at Regimanuel Gray (Ghana) Ltd.

Simon Suwanzy Dzreke1, Manasey Franklin Dzreke2

1Department of Defense, Alion Science and Technology, Crane, IN, USA

2School of Business & Technology, University of Professional Studies, Accra, Ghana

Copyright © 2016 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received 16 December 2015; accepted 17 January 2016; published 21 January 2016

ABSTRACT

Three problems were identified in this study. The first aspect of the problem is that Ghana’s housing market is not affordable for many lower-income Ghanaians, in contravention of the Government of Ghana’s goal of creating a more affordable housing market. The second aspect of the problem is that it is not known whether the Government of Ghana’s corporate income tax incentive for low-cost housing developers has been successful in raising income for developers. The third aspect of the problem is that Regimanuel Gray (Ghana) Ltd. does not yet have a sound empirical basis on which to weigh low-cost versus non-low-cost housing projects in its portfolio. The objective of the study was to determine whether tax incentives at Regimanuel Gray (Ghana) Ltd. were positively associated with company income. It was found that there was a) a statistically significant (p < 0.01) difference between mean income associated with low-income housing (M = $12,567,370, SD = 1,324,085) and mean income associated with non-low-income housing (M = $139,639,000, SD = 6,095,264) and b) a statistically significant (p < 0.01) difference between mean ROI associated with low-income housing (M = 1.415, SD = 0.1721062) and mean ROI associated with non-low-income housing (M = 15.948, SD = 1.226073). The contribution of the study was thus to discover that it is economically inefficient for Regimanuel Gray to engage in low-cost housing projects under the current tax break scheme. The main recommendations emerging this analysis are that a) Regimanuel Gray ought to dedicate more of its productive resources to non-low-cost housing and b) Regimanuel Gray ought to press the government harder for more tax incentives to build low-cost housing.

Keywords:

GDP: Gross Domestic Product, NPV: Net Present Value, QRSUTs: Quality Residential Sprawls with Unicentric Tendencies, ROI: Return on Investment, Tax Revenue, Neoclassical Theory of Economic, The Marginal Effective Tax Rate (METR) of an Investment, Affordable Housing

1. Introduction

Tax revenue, from organizations as well as from individuals, is an essential component of Ghana’s gross domestic product (GDP). From 1990 onwards, Ghana has obtained between roughly 10% and 21% of its GDP from taxes ([1] World Bank, 2014). Corporate taxation remains an indispensable constituent of Ghana’s tax revenue. However, there remains an umpteen tension between the Ghanaian state’s desire to foster commercial activity within the country and the inevitability of redistributing income to Ghana’s numerous impecunious citizens. According to World Bank data, 30.6% of all Ghanaian businesses identified the national corporate income tax rate of 25% as being a protracted encumbrance on business success. This sky-scraping comparable of business chagrin with corporate income tax exists despite the fact that Ghana prune the corporate income tax rate from 35% in 1998 to 32.5% in 2000 and then again to 25% in 2006, where the rate has remained ever since (World Bank, 2014).

In 1983, Ghana instituted a structural adjustment program that accentuated the role of the private sector rather than the state in the provision of goods and services. [2] Arthur (2006) has argued that Ghana’s pro-business prominence has become sturdier over the years. According to Arthur, the Ghanaian state remains censurable not only for facilitating the environments in which private businesses can burgeon, but also to ensure that, in one way or another, businesses can proffer goods and services that they might not otherwise provide the country’s population. Achieving this compassionate of balance is not a policy goal that remains inimitable in Ghana. Neoclassical theorists have long enunciated that, in unrestricted market, businesses will gravitate towards the most cost-effective activities, leaving it up to the state to either provide less money-spinning goods and services or to generate incentives to stimulate private businesses to provide these goods and services ( [3] Krugman & Wells, 2009).

In an unindustrialized economy, profitability metamorphoses between industries can be gargantuan (Krugman & Wells, 2009). In the case of Ghana, certain industries (especially energy, petroleum, and finance) are highly cost-effective (Arthur, 2006). One of the glitches encountered by the Ghanaian state in its neoliberal, pro-busi- ness era is how to incentivize businesses to generate goods and services for industries that are not as lucrative. The orthodox method to this quandary is for governments to utilize tax breaks and other incentives to create distortions in the market favoring companies that are alacritous to provide less profitable goods and services (Krugman & Wells, 2009). In this approach, each party engrosses in the task in which it is most efficient: Government with the task of managing tax revenues so that it is parsimoniously feasible to create corporate income tax breaks, and private business in the task of spawning goods and services (Krugman & Wells, 2009). For corporate income tax incentives to work as premeditated there must be a balance between the size of the tax break and what is produced by private industry (Krugman & Wells, 2009). If the tax break is too hefty, efficiency is lost, as the government might abnegate an inordinate aggregate of revenue for an insufficient redistribution of economic activity. If the tax break is too trifling, the government cannot thrive in redistributing economic activity in alignment with policy goals. For this reason, it is imperative to be able to study the relationship between corporate income tax incentives and other outcomes, such as vicissitudes in corporate income, that can signpost government success in motivating new-fangled forms of economic behavior among private businesses. The focus of this study is on the relationship between corporate income tax and corporate income in an important Ghanaian real estate corporation.

There is a momentous scarcity of low-cost housing in Ghana. This fact can be ingrained by statistics supplied by the [4] Bank of Ghana (2007), according to which the market prices for five categories of houses in Accra, Ghana were as follows (Table 1).

As of 2012, the trailblazing year for which data are accessible, the World Bank (2014) predicted that the gross coast-to-coast income per capita of Ghana was $1550. Grounded on this calculation, the cost of a 140 m2 house in Accra is agnate to 24 years of the average Ghanaian’s labor, representing a contemplative affordability problem of which the government of Ghana has long been cognizant. For over an epoch, the Ghanaian govern-

Table 1. Cost of five kinds of houses in Accra, Ghana.

Note: Data obtained from the Bank of Ghana (2007, p. 28).

ment has provided a tax incentive for companies that build low-cost housing in the country [5] Awuvafoge (2013). The tax incentive is that companies building low-income housing are excepting on income originating from such housing for a period of 5 years, after which taxation resumes at the regular corporate taxation rate of 25% ( [6] Ernst & Young, 2014).

As the Bank of Ghana (2007, p. 21) indicated, Ghanaian real estate is dominated by one company, Regimanuel Gray, which is responsible for jaggedly 50% of dwellings in the country. Regimanuel Gray and the other home-builders active in Ghana (including NTHC Properties Ltd., Devtraco, Trasacco Estates, and others) have, notwithstanding the actuality of the tax incentive outfitted by the government, chosen to focus their activities on the construction of middle- and higher-cost dwellings (Bank of Ghana, 2007, p. 21). Given that the Government of Ghana (2013) has long prioritized the construction of low-cost housing as a principal policy, it is natural to interrogate whether the 5-year remission of corporate tax correlated to income from low-income housing has thriven in tilting the economics of Ghana’s housing market towards the country’s lower-income population. If the Government of Ghana’s tax incentive has not been efficacious, then there would be a virtuous reason for the state to recrudesce the subsisting policy in the indulgence of a supplementary operative method. If the tax incentive has been propitious, then the government has gnarly reason to preserve the incentive in effect.

One way to determine whether Ghana’s tax incentive has been efficacious is to scrutinize the relationship between the incentive and the number of lower-cost units built by particular real estate companies. However, one problem with this approach is data accessibility, as obtaining clear-cut records about units constructed is effortful. Another approach is to anatomize the relationship between the independent variable of the corporate tax incentive for low-income housing development and the dependent variable of corporate income. If the relationship between these dualistic variables is positive, then there would be wide-ranging, albeit indirect succor for the conclusion that the tax incentive is working; after all, the objective of the tax incentive provided by the Government of Ghana (2013) is to make it supplementary cost-effective for companies to give a whirl in low-cost housing expansion, which is not customarily a money-spinning profession for Ghanaian construction and real estate companies (Bank of Ghana, 2007, p. 21). If the tax incentive is undeniably concomitant with increasing corporate income, then the government’s tax incentive could be weighed as being operative in its central goal, and it could also be acknowledged that market forces would fascinate innumerable Ghanaian developers to the low-cost housing market. The question of whether the corporate tax incentive provided to low-cost housing developers is indubitably connected with corporate income remains to be reconnoitered empirically.

1.1. Problem Statement

The problem is threefold. The first aspect of the problem is that Ghana’s housing market is not affordable for voluminous lower-income Ghanaians, in contravention of the Government of Ghana’s goal of generating a supplementary affordable housing market. The second aspect of the problem is that it is not known whether the Government of Ghana’s corporate income tax incentive for low-cost housing developers has been successful in raising income for developers. As such, the Government of Ghana does not have sufficient empirical patronage for determining whether to continue or alter its corporate income tax incentive for low-cost housing developers. The third aspect of the problem is that Regimanuel Gray (Ghana) Ltd. does not yet have an all-encompassing empirical basis on which to weigh low-cost versus non-low-cost housing projects in its portfolio.

1.2. Research Question and Hypothesis

The purpose of the project is to determine whether tax incentives at Regimanuel Gray (Ghana) Ltd. are positively associated with company income. In order to achieve this purpose, the following research questions have been posed:

RQ1: Is there a statistically significant association between the existence of Ghanaian corporate income tax incentives and income at Regimanuel Gray (Ghana) Ltd.?

H10: There is not a statistically significant association between the existence of Ghanaian corporate income tax incentives and income at Regimanuel Gray (Ghana) Ltd.

H1A: There is a statistically significant association between the existence of Ghanaian corporate income tax incentives and income at Regimanuel Gray (Ghana) Ltd.

RQ2: Is there a statistically significant difference between the 10-year profitability, calculated as return on investment (ROI), of all of Regimanuel Gray (Ghana) Ltd.’s low-cost housing projects and non-low-cost housing projects in Ghana?

H20: There is not a statistically significant difference between the 10-year profitability, calculated as ROI, of all of Regimanuel Gray (Ghana) Ltd.’s low-cost housing projects and non-low-cost housing projects in Ghana.

H2A: There is a statistically significant difference between the 10-year profitability, calculated as ROI, of all of Regimanuel Gray (Ghana) Ltd.’s low-cost housing projects and non-low-cost housing projects in Ghana.

RQ1 addresses the question of whether the existence of a corporate income tax is proportionate with increased corporate income at Regimanuel Gay (Ghana) Ltd. RQ2 is a means of directly juxtaposing the profitability of Regimanuel Gray (Ghana) Ltd.’s low-cost housing projects and non-low-cost housing projects in Ghana in order to discern patterns, if any, in the longer-term profitability dynamics of these two kinds of housing. The expected output from RQ1 is a multiple regression model while the expected output from RQ2 is a matched pairs t-test model.

In order to answer the first research question, the following statistical steps will be taken. First, data will be gathered for Regimanuel Gray (Ghana) Ltd.’s net income for the past 10 years. Contact with a high-level manager at Regimanuel Gray (Ghana) Ltd. has already been made; the manager has already enabled access to all demanded data in a spreadsheet format. Net income will constitute the dependent variable in this research question. Next, data will be gathered for a) income attributable to low-cost housing and b) income not attributable to low-cost housing, both of which will be treated as independent variables. Next, multiple regression will disclose the distinct contribution of each independent variable to change in the dependent variable as well as the interaction, if any, between the independent variables. Although the corporate income tax incentive is not directly captured in this research question, it is still an implicit variable in that the existence of such an incentive is likely to have been responsible for income derived from low-cost housing. Finally, an independent samples t-test will determine whether the difference between income generated by low-cost housing is significant different from income generated by non-low-cost housing.

In order to answer the second research question, the following statistical steps will be taken. First, data will be gathered for the profitability, calculated as ROI, for each of Regimanuel Gray (Ghana) Ltd.’s housing projects in Ghana over the past 10 years. Next, the data will be divided into two independent groups, a) yearly profitability for low-income housing developments and b) yearly profitability for non-low-income housing developments. Afterwards, the figures will be averaged, such that every year will be associated with an a) average profitability figure for low-income housing developments and b) an average profitability figure for non-low-income housing developments. Next, multiple regression will disclose the distinct contribution of each independent variable to change in the dependent variable as well as the interaction, if any, between the independent variables. Finally, an independent samples t-test will be conducted to determine whether the mean profitability of low-income housing developments is lesser than, greater than, or the same as the mean profitability of non-low-income housing developments.

1.3. Profile of Organization

Regimanuel Gray remains the organization that will provide the data on the basis of which the relationship between the Government of Ghana’s corporate income tax incentive and corporate income will be tested. Regimanuel Gray has commercial interests not only in Ghana but also in Sierra Leone and other countries in West Africa ( [7] Regimanuel Gray, 2014). Regimanuel Gray is a joint venture, founded in 1991, consisting of Ghana’s Regimanuel Ltd. and the United States of America’s Gray Construction (Regimanuel Gray, 2014). Although Regimanuel Gray claims to promote affordability as one of its building criteria, the company is internationally known for being among the pioneers of gated communities in West Africa, including Ghana ( [8] Asiedu & Arku, 2009; [9] Grant, 2005). On the basis of two decades of demographic and land use survey evidence, [10] Yeboah (2003) concluded that Regimanuel Gray Ltd. and other housing developers profited largely by turning Accra and other metropolis in West Africa into so-called quality residential sprawls with unicentric tendencies (QRSUTs). A QRSUT, according to Yeboah, reflected a housing market dominated by immense economic differences between high- and low-cost housing, an appropriation of the finest land for high-cost housing, and, in short, a domination of the housing market by the interests of the wealthy.

Regimanuel Gray (Ghana) Ltd. was the subject of an empirical study in which [11] Boye (2012) determined that over 97% of the variation in the housing unit price in the company’s Ghanaian projects was associated with variation in the four independent variables of number of apartment units, plot size, gross area, and number of site parking spaces. Boye’s findings indicate that Regimanuel Gray (Ghana) Ltd.’s profitability appears to require the use of large lots and large living spaces, both of which are associated with the emergence of wealthy urban conclaves in Accra and other West African metropolis (Yeboah, 2003). At the same time, Regimanuel Gray has been involved in the construction of some notable low-cost housing projects and devotes considerable rhetoric to the importance of such projects in its corporate mission (Regimanuel Gray, 2014). Because Regimanuel Gray (Ghana) Ltd. does not provide an official mission or objective for itself, conclusions about the company’s strategy have to be reached on the basis of empirical analysis (such as those conducted by Boye, 2012) as well as on the basis of an analysis of Regimanuel Gray (Ghana) Ltd.’s Web site.

1.4. Significance of the Study

Ghana has made significant strides in reducing poverty over the past three decades. Data from the World Bank (2014) indicate that the percentage of Ghanaians living on $1.25 a day, a commonly accepted criterion for global poverty, declined by roughly 45% from 1988 to 2006, the latest year for which the Government of Ghana has provided the World Bank with data. The decline in the percentage of all Ghanaians living on $1.25 a day can be observed in Figure 1.

There has been a similar decline in the $2 poverty gap. Data from the World Bank (2014) indicate that the percentage of Ghanaians living on $2 a day, another commonly accepted criterion for global poverty, declined by roughly 41% from 1988 to 2006, the latest year for which the Government of Ghana has provided the World Bank with data. The decline in the percentage of all Ghanaians living on $2 a day can be observed in Figure 2.

Figure 1. Ghanaian $1.25 poverty gap, selected years. Note: based on World Bank (2014) data.

Figure 2. Ghanaian $2 poverty gap, selected years. Note: based on World Bank (2014) data.

The World Bank (2014) data suggest that Ghana has experienced an evocative enfeeblement in poverty. However, as the Government of Ghana (2014) has noted, countless Ghanaians still remain incapable to purchase a home. Given that possessing a home vestige a supreme hallmark of security and happiness betwixt West Africans (Asiedu & Arku, 2009; Grant, 2005), the low affordability of Ghanaian housing remains not only a policy dilemma for the government but also an impediment to the well-being of copious Ghanaians. While the Government of Ghana has created a corporate income tax incentive to induce supplementary inventors to create low-income housing, it is not clear whether this dogma has been efficacious. The connotation of the contemporary study lies in the probability that the empirical archetypal can a) detect the contribution of the corporate income tax incentive on the corporate income of the premier Ghanaian housing inventor; and b) compare the profitability of low and non-low-cost housing erected by this developer. Objective a) will constitute empirical support for continuing or revising the Government of Ghana’s contemporary corporate income tax incentive structure while objective b) will offer insights into how profitability might steer developers such as Regimanuel Gray (Ghana) Ltd. towards either low- or non-low-cost housing development on the basis of market forces. Accomplishing both of these objectives will constitute an imperative contribution to the burgeoning literature on the relationship between corporate income tax and corporate income in West Africa, on the basis of a social and economic problem that is of the utmost importance to both the government and the population of Ghana.

1.5. Limitation of the Study

The first limitation grappled with in this study was the identification and execution of appropriate statistical methods that could quantify the effect of the government of Ghana’s tax breaks on Regimanuel Gray’s income and ROI. The second limitation defied in this study was obtaining the appropriate data from Regimanuel Gray, systematized into a format that could fulcrum data analysis. The third drawbacks of the study were the identification of theories and empirical studies that address the relationship amid tax policies and innumerable facets of corporate performance.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Problem Statement

The tenacity of this segment of the chapter is to delineate and divulge the answers that are indispensable to execute the study. Wherever conceivable, these incumbencies will be accompanied by schedules. The responsibilities are chronologically presented.

First, data will be obtained from Regimanuel Gray (Ghana) Ltd. Contact with a high-level manager at Regimanuel Gray (Ghana) Ltd. has already been made; the manager has already enabled access to all demanded data in a spreadsheet format. Data were congregated in the following (Table 2).

Second, the data salvaged from Regimanuel Gray (Ghana) Ltd. will be transferred to SPSS version 20.0 for statistical analysis. SPSS will be used to a) pucker and present descriptive statistics for the data, b) answer the first research question of the study, and c) answer the second research question of the study. Statistical analysis will take place from July 1, 2014 to July 3, 2014.

Third, the results salvaged from the statistical analysis will be rummage-sale to inform the writing of Chapters 3, 4, and 5 of the study between July 3, 2014 and July 10, 2014.

2.2. Explanation of Theories

The cardinal theory utilized in this study is the theory of tax incentives. However, this theory is itself fragment of a considerable preponderant and broader theory, that of neoclassical economics operating in a free or relatively unrestricted market. For this reason, before discussing the theory of tax incentives in speculative circumstantiality, it is quintessential to discuss part of the doctrines and precepts of neoclassical economics.

One of the nitty-gritties of neoclassical economics is the postulation that, in a comparatively unrestricted market, economic actors will make pronouncements constructed on self-interest, which [12] Adam Smith (1801), in his revolutionary book The Wealth of Nations, depicted as an amalgamation of maximizing benefits while curtailing costs. According to Smith, this system of economic egocentricity was epitomized by market activities premeditated to upsurge profits while plummeting the risk of monetary loss.

Each economic actor, whether individual, corporate, or governmental, has an irreplaceable technique of propelling cost-benefit analyses and determining how, when, and why to engage in economic activity (Smith, 1801). For businesses in particular, the choice of economic activity is habitually governed by the consideration of short- and long-term profitability. Simply put, businesses that do not anticipate the direct or indirect profitability of a particular system of economic performance do not gradient to participate in that behavior ( [13] Feldstein, 1974), which is pedantically aligned with the neoclassical theory of economic behavior articulated by Smith.

The cost-benefit considerations of economic behavior are highly germane to the theory of tax incentives. The theory of tax incentives has numerous key premises related to economic behavior. The first and perhaps furthermost imperative premise is that, in the absence of a favorable cost-benefit calculus, the chances of individuals or businesses engaging in a particular system of economic behavior are lower (Feldstein, 1974; [14] Russo, 2004). The second premise of the tax incentive theory is that there are some forms of economic behavior―and, for that matter, social behavior―that are constructive to a society (Krugman & Wells, 2009). Combining these premises leads to the conclusion that certain systems of desirable economic and social behavior are improbable to be practiced by market actors. For example, running a fire department is a highly unprofitable enterprise, which is why fire departments are characteristically run by governments and volunteers, with minimal participation from business.

Table 2. Data format for study.

If certain forms of desirable economic and social behavior are questionable to be practiced by market actors, then, in theory, a government that wants to bring about these forms of behavior has essentially two options: Coercive and incentive-based. In a coercive approach, a government can mandate certain forms of economic behavior, thus compelling businesses to inveigle in specific industries or provide specific services ( [15] Usher, 1977). In an incentive-based approach, a government eschews coercion in favor of positive motivation (Usher, 1977). Specifically, by creating an innumerable favorable cost-benefit calculus, a government can engender a natural incentive for businesses to dovetail in specific systems of economic activity.

Generating a supplementary auspicious cost-benefit calculus for businesses is repeatedly the monarchy of tax incentives. Theoretically, a tax incentive makes it additional profitable for a business to engross in the behavior for which government has shaped an incentive, thus making it more prospective that businesses will act in a manner acceptable to government. In a way, tax incentives are a payment from government to business, a payment that can compensate a business for engaging in an activity that would not ordinarily be profitable (Feldstein, 1974; Krugman & Wells, 2009; Russo, 2004).

The theory of tax incentives is thus a simple extension of the logic of neoclassical economics. Businesses, like other economic actors, engage in certain economic behaviors on the assumption that these behaviors are likely to be profitable (Smith, 1801). Governments often have a need to embolden businesses to engage in economic behaviors that might not be profitable for the businesses, but that are beneficial for society as a whole (Krugman & Wells, 2009). In some cases, governments do not have this need, because they can engage in certain forms of economic activity themselves. For example, a government that already controls public resources for housing development can utilize these resources to develop low-cost housing. However, in pauperized states such as Ghana, governments often do not possess certain resources of their own and are therefore more dependent on private sector actors in order to achieve certain social goals ( [16] Yelpaala, 1984). It is in this theoretical context of both neoclassical economic theory and one of its offshoots, tax incentive theory, that Ghana’s corporate income tax break to low-cost housing developers can best be understood.

If the theory of tax incentives is spot-on, then plummeting the corporate income tax rate for Ghanaian companies that generate low-cost housing is prospective to dynamize curiosity in this form of economic activity amid companies such as Regimanuel Gray (Ghana) Ltd. However, on its own, the theory of tax incentives does not answer many important empirical questions that are necessary to cognize the ligament between tax incentives and economic behavior ( [17] Klemm & Van Parys, 2012). In particular, tax incentive theory does nothing to answer the interrogative of how outsized a tax incentive has to be in order to embolden the desired economic behavior. Resolving this question is a matter of empirical analysis based on calculating the relationship between the independent variable of tax incentives and the dependent variable of economic behavior. Another empirical question of particular attentiveness in the context of a study of Ghanaian low-cost housing is whether there is a relationship between a corporate income tax incentive and corporate income. As opined by Smith (1801), neoclassical economic theory predicts that an incentive such as a tax break is likely to be worthwhile only insofar as it actually alters the cost-benefit calculus for a company, and one of the most powerful measures of cost-benefit analysis is income. Grounded on the framework of neoclassical economics and the theory of tax incentives, two empirical claims can be made. The first claim is that companies that experience a growth in corporate income attributable to a corporate income tax incentive are more likely to engage in the form of economic behavior that is being promoted by a government. The second claim is that it is not adequate for a company to experience income growth attributable to a tax break; this income growth must be comparable to, or greater than, the income growth attributable to some form of non-sanctioned behavior. Translated into the context of this study, these two empirical assertions are that a) Ghanaian building developers are more probable to build low-cost housing if there is positive income growth correlated with such behavior and b) Ghanaian building developers are even more likely to build low-cost housing if the income growth from doing so is comparable to, or greater than, the income growth from building non-low-cost housing. These are the assertions that are being scrutinized in the research questions modelled in this study. The focal tenacity of the next section of this chapter, the empirical literature review, is to determine what empirical precedents exist for evaluating these kinds of assertions.

2.3. Empirical Literature Review

The discussion of neoclassical economics and tax incentive theory in the antecedent section of this chapter led to two empirical assertions about the nature of economic behavior under a corporate income tax incentive. The first such claim mediatized on the inevitability for income growth attributable to a corporate income tax break; without such income growth, businesses in a comparatively unrestricted market are prospective to malaise to participate in the form of economic behavior promoted by a government. The second such claim centralized on the desideratum for a certain level of income growth attributable to a corporate income tax break. As businesses archetypally have several choices about the uses to which they can put their productive resources, it is not enough for a corporate income tax incentive to result in income. The amount of income excogitates from the economic behavior motivated by the income tax break should be comparable to the income that can be derived from economic behavior unrelated to the income tax break. One of the purposes of the empirical literature review is to survey and evaluate past empirical studies in order to determine whether these claims are valid, and, if so, how businesses have engaged in cost-benefit calculations correlated to corporate income tax breaks. This discussion will help to exculpate the hypotheses specified in the first chapter of the study and endow important background information against which the empirical analysis of Regimanuel Gray (Ghana) Ltd.’s economic behavior relative to low-cost housing can be understood.

Another tenacity of the empirical literature is to review changes in Ghana’s housing policy and requirements over the past several years. The existence of corporate income tax breaks for low-cost public housing providers in Ghana cannot be tacit without first reviewing the evolution and current state of Ghanaian housing policy. The two purposes of the literature review connect with that Ghana’s housing policy is not likely to work if there is little chance that the corporate income tax break for low-income housing providers does not result in a quantifiable change in income.

2.4. The Ghanaian Context

[18] Arku (2009) furnished an enthralling elucidation of why Ghana initiated a corporate income tax break for private companies providing low-cost public housing. According to Arku, Ghana’s first methodology to the enigma of inadequate housing for the country’s low-income population, predominantly in ponderously populated areas such as Accra, was based on the utilization of public resources. According to Arku, there were two paramount reasons that the state of Ghana turned to private companies to become supplementary active in the provision of public housing. The first reason was that Ghana’s public low-cost housing initiatives had limited triumph. Arku christened attention to “the fiasco of public housing programs, dwindling state resources, mediocre performance of state-owned enterprises, and recognition that the government alone is impuissant to solve the housing problem” (p. 261) as puissant motivating factors for Ghana’s turn to private sector housing developers in the 1990s. Other scholars have noted the limited success of the Ghanaian government in building public housing. For example, [19] Tipple and Korboe (1998) noted that the State Housing Corporation (SHC) of Ghana became well-known for building extremely trifling dwellings and concluded that “the state sector had demonstrably failed to meet targets and absorbed extra resources and attention than its output should have merited” (p. 246). In addition to the catastrophe of public housing ingenuities in Ghana, Arku also acknowledged the imperative role frolicked by the global proliferation of neoliberal ideologies in which private sector activity is reinvigorated over public sector activity in the endowment of housing and other key services and products consumed by society.

While Ghana’s means of spawning innumerable low-cost housing have altered over the past two decades, the goal has remained the same: To meet the government’s 1993 National Shelter Strategy, which prioritizes the provision of housing as an intrinsic right for Ghanaians (Tipple & Korboe, 1998). Ghana, comparable to myriad other Sub-Saharan African Countries, has experienced an expeditious intensification in its population, and principally in its municipal population, that has created challenges in terms of fulfilling the National Shelter Strategy ( [20] Obeng-Odoom & Amedzro, 2011). The pressure on Ghana to escalate its supply of housing, and exclusively the low-cost housing that is within the economic reach of greatest Ghanaians, have been augmented by the fact the prevailing housing is often blunderingly preserved and otherwise derisory (Obeng-Odoom & Amedzro, 2011). Officially, Ghana taxonomies imperceptibly structure with a roof as a building (Bank of Ghana, 2007), and, as Obeng-Odoom and Amedzro noted, countless of the surviving building structures do not accord with acceptable safety or comfort standards.

There is thus ample support in the literature (Arku, 2009; Bank of Ghana, 2007; Obeng-Odoom & Amedzro, 2011; Tipple & Korboe, 1998) to underpinning the assertion that Ghana’s public approach to the provision of low-cost housing has botched and that the utilization of private companies has become a massed promising alternative. What is not as crystal is the extent to which private companies, especially in the wake of the corporate income tax incentive offered by the state of Ghana, have engaged in the construction of appropriate low-income housing. One of the discontinuities in the already exiguous academic and professional literature on Ghanaian housing is the vacuity of data on low-income housing development as a result of private sector activity.

What is known is that there are numerous market palpitations on Ghanaian housing developers to quintessence their economic activities on the construction of innumerable rather than less expensive housing. [21] Boamah’s (2011) analysis of the Ghanaian housing finance market revealed that, due to the immaturity of lending practices, even divers middle-class Ghanaians often skirmish to raise the money to purchase decent homes. Conversely, Ghana has also experienced globalization over the past two decades, resulting in the emergence of a loftier class of wealthier Ghanaians who can afford better homes. [22] Knadu-Agyemang (2001) has pointed out the accumulative bifurcation of Ghanaians into a) a hefty class of people (including workers, agriculturalists, and women) who have, especially as a result of the economic policies imposed on Ghana after the 1983 Structural Adjustment Program (SAP) sponsored by the International Monetary Foundation (IMF) and World Bank, experienced mounting paucity and b) a smaller class of people who have benefited parsimoniously from globalization and the new direction of Ghana’s economy. Despite Ghana’s success in plummeting poverty at the $1.25 and $2 gap levels (see Figure 1 and Figure 2 in Chapter 1 for an illustration of these trends), Ghana remains an underprivileged country, one in which housing developers can profit more by serving the wealthy or relatively wealthy.

There is some empirical evidence that Regimanuel Gray (Ghana) Ltd. has been active in the low-cost housing market in Ghana. In 2011, Regimanuel Gray (Ghana) Ltd. embarked on the construction of a 17,000-unit low- cost housing project at Katamanso, completing prevailing low-cost housing projects (also known as estate houses) in Tema, East Airport, Teshie Nungua, Essipong, and Kwabenya ( [23] Anonymous, 2011). At the same time, Regimanuel Gray (Ghana) Ltd. has continued to build gated communities and other expensive housing throughout Ghana (Asiedu & Arku, 2009). One of the empirical questions to be settled in this study is just how much income as well as return on investment (ROI) Regimanuel Gray (Ghana) Ltd. generates from both low-cost and non-low-cost housing. Income is a virtuous proxy measure of the number of low-cost housing units built by Regimanuel Gray (Ghana) Ltd., and can therefore serve to illustrate how extensively the company is involved in low-cost housing development.

In the Ghanaian context, one in which to understand the linkages amid corporate tax incentives, economic behavior, and corporate income is to scrutinize the changing nature of the housing market. [24] Grant’s (2007) analysis of the housing market in Ghana demonstrated that, from independence to about 1980, the state acquired 15% of all urban land for development purposes. As late as 1990, 15% of the household dwellings in Ghana were owned, and had been built, by the government during the era of predominantly public housing. Despite the flurry of public activity, Grant noted that most residential dwellings, both in Accra and in the rest of the Ghana, were not the property of the state, but rather of private individuals. In Ghana’s traditional property system, residential dwelling was based on the use of compounds in which several persons or families lived, and which were seldom sold.

Grant (2007) argued that the traditional Ghanaian compound-based housing system was sufficient to meet the country’s housing needs until the 1970s, when population growth accelerated. As Ghana’s population grew, compounds became progressively inefficient; as Grant pointed out, a compound built on land that could hold perhaps 20 people could hold many times that number in a more modern, vertically built structure such as an apartment complex. Demographic changes resulted in market changes, as the compound system proved to be unsustainable and was increasingly replaced by a private housing market. The change was relatively expeditive. Grant’s research indicated that, in 1990, traditional compounds represented 62% of the housing stock in Ghana; by 2000, compounds were only 42.5% of the housing stock. In the same time period, the percentage of apartments augmented over 700%, going from 1.2% of all housing stock in 1990 to 8.8% of all housing stock in 2000. In the same time period, government fundamentally extricated itself from housing. In 1990, the government owned 15% of all housing stock; by 2000, this figure declined precipitously to merely 3.96% of all housing stock.

These data suggest the emergence of a new income opportunity for private Ghanaian housing developers such as Regimanuel Gray (Ghana) Ltd. From 1990 to 2000, Ghana experienced a mass transfer of land from compound owners and the government to private developers, who now had a fortuitous to engage in supplementary efficient development on the newly acquired land. However, there are no empirical data on whether the provision of a corporate income tax actually prompted developers such as Regimanuel Gray (Ghana) Ltd. to give a whirl in the construction of low-income housing to the extent considered indispensable by the government. Because of the vacuity of empirical data in the Ghanaian context, it is quintessential to turn to empirical stories converging on other countries and contexts in order to learn whether corporate income tax breaks are associated with desired vicissitudes in businesses’ economic behavior as measured by upsurges in corporate income and other factors.

2.5. Corporate Tax Incentives, Economic Behavior, and Corporate Income

Empirically, the consanguinity betwixt corporate income tax and corporate income is characteristically measured by applying tax provisions to the marginal effective tax rate (METR) of an investment ( [25] Zee, Stotsky, & Ley, 2002). Large companies often have numerous different projects whose METRs are different. The World Bank (2014) has noted that, in Malawi, METRs gravitated to diverge from 47% to 67% notwithstanding the permanence of a monolithic taxation rate of 50%. The reason for this variation in METRs, when applied to the integrated portfolio of a company’s income-generating activities, is that states employ convoluted systems of tax incentives. In Ghana, for example, there is a 5-year tax break for all income culminating from a low-cost housing project (Government of Ghana, 2013). Thus, a company such as Regimanuel Gray (Ghana) Ltd. that has a portfolio of low-cost as well as non-low-cost housing projects will not, in a given year, pays the official tax rate of 25%. Depending on the mix of low-cost and non-low-cost projects in a housing developer’s portfolio, the cumulative METR could be considerable percentage points lower than the official tax rate. In a fragment calculation, [26] Pellechio, Sicat, and Dunn (1987) analogized how an investment with a METR of 45.6% would have a METR of 29.3% as the corollary of a 5-year tax break of the kind that is currently being offered in Ghana to low-cost housing developers. Pellechio et al. pointed out that a 5-year tax break was not the solitary means of menacing the METR of a project such as a low-cost housing project; these kinds of tax breaks can be combined with other incentives and strategies, such as investment tax credits, exemption from import duties on capital goods, and investment deductions to result in an even lower METR.

In the context of the ability of tax incentives to alter economic behavior, the efficacy of empirical studies such as those of Pellechio et al. (1987) is the analogy of what might be called break-even points. In Ghana, non-low- cost and high-low-cost housing each has their METRs, which in turn inform the return on investment (ROI) that can be derived from these kinds of projects. Using Pellechio’s example, if the METR of non-low-cost housing is 45.6% and the METR of low-cost-housing is 29.3%, the case for a company such as Regimanuel Gray (Ghana) Ltd. to shift its economic behavior to the development of low-cost housing becomes tenacious. However, the break-even point in terms of ROI is not dependent exclusively on the METR, nonetheless rather on the comprehensive return on the project. It is possible for the METR of an ultimately unprofitable project to be low, nonetheless the profitability of such a project to also be low.

For this reason, the categories of diminutions in METR that can be brought about by tax incentives such as the 5-year tax holiday offered by Ghana to low-cost housing developers need to be well-thought-out in light of some weightier framework of ROI. In the case of housing in particular, the empirical challenge of constructing such an ROI analysis is that, in cases in which a private developer such as Regimanuel Gray (Ghana) Ltd. is renting rather than selling, the value of a housing project unfolds over the years or even decades of the serviceable life of a building. In the case of low-cost public housing in Ghana, there is a testimony that rental vestiges a popular means for lower-income people to inhabit dwelling spaces, not merely because of their lack of financial resources to purchase a home but also because of the immaturity of the Ghanaian housing finance market noted by Boamah (2011). In fact, even when dwelling spaces are purchased, the lifetime value of a building can be contingent on factors such as the costs of demolition, the resale value of construction materials, and the value of the land itself at some point in the future. Because of all these factors, simple METR comparisons are not a sufficient means for companies to decide between projects that are accompanied by corporate income tax breaks and projects that are not accompanied by income tax breaks. Rather, real estate developers tend to use the net present value (NPV) framework as an empirical means of comparing the long-term value of an investment such as housing development ( [27] Greer & Kolbe, 2003). NPV is a formula that adds the discounted sum of all cash flows received from a project (Greer & Kolbe, 2003). In the present study, the variable of cash flow as normally associated with NPV is coded as income attributable to low-cost and non-low-cost housing.

Research suggests that housing developers use NPV extensively in order to decide between competing projects, and that METR breaks created by tax incentives such as tax holidays are only part of the grandiose cost-benefit analysis carried out by developers (Greer & Kolbe, 2003). What is particularly prohibitive for government is to aspire to determine a METR break that is presumable to result in a desired transformation in economic behavior. The reason for this paradox is that governments do not inevitably have the resources or the institutional motivation to empirically study vicissitudes in the private sector’s economic behavior on the basis of adjustments to tax incentives. In the case of Ghana, for example, the 5-year tax holiday policy for low-cost housing development has been fixed for several years (Government of Ghana, 2012) notwithstanding the seeming vacuity of data that empirically validate this policy. In the vacuity of NPV or a similar form of analysis, there is no valid means of determining the magnitude to which Ghanaian tax policies are culminating in the anticipated forms of transformation in the economic behavior of private housing developers.

2.6. Conclusion of the Empirical Literature Review

The purpose of this concluding section of the empirical literature review is to relate the two research questions of the study to the empirical literature as well as to some of the economic theories deliberated preceding in the chapter. The two research questions of the study are as follows:

RQ1: Is there a statistically significant association between the existence of Ghanaian corporate income tax incentives and income at Regimanuel Gray (Ghana) Ltd.?

RQ2: Is there a statistically significant difference between the 10-year profitability, calculated as return on investment (ROI), of all of Regimanuel Gray (Ghana) Ltd.’s low-cost housing projects and non-low-cost housing projects in Ghana?

The first research question is entrenched determinedly in neoclassical theory’s prediction that economic behavior is predicted by an economic actor’s cost-benefit exploration (Smith, 1801). If the Ghanaian 5-year corporate income tax holiday for income concomitant with low-cost housing development is operative, then it stands to reason that there would be a substantial homogeneity betwixt Regimanuel Gray (Ghana) Ltd.’s principally income and the company’s income for low-cost housing. In fact, given the enigmatic portfolio rapport that can endure in real estate (Greer & Kolbe, 2002), there might even be synergetic effect amid the variable of income from low-cost housing and income from low-cost housing. Conceivably, Regimanuel Gray (Ghana) Ltd.’s engagement in low-cost housing is contriving supplementary arrays of income opportunities, for example by ameliorating the company’s brand or otherwise humanizing the company’s capability to participate in non-low-cost housing. If this kind of effect exists, then it should be empirically detectable by forging a parallel variable (income from low-cost housing * income from non-low-cost housing) for the regression in the first research question. Greer and Kolbe’s work suggest that such an analogy is possible.

The second research question, while also forage in both neoclassical and tax incentive theory, reconnoiters an empirical characteristic of tax incentives that was advocated, nevertheless not vociferously discussed, in Pellechio et al.’s (1987) work, which is the ongoing value of lower-METR income over time. A tax holiday of 5 years can profoundly pauperize METR in year 1 of an investment, conversely, in the case of housing; returns will presumptively persist for considerable years beyond the tax holiday, necessitating a longitudinal approach to the analysis of profitability. If Regimanuel Gray (Ghana) Ltd. is involved in a sufficient number of low-cost housing projects, and has learned to curtail the construction costs associated with such projects down, then it is possible that a longitudinal (in this case, 10-year) analysis will demonstrate that the profitability of low-cost housing developments is at least on par with the profitability of non-low-cost housing developments.

Income and ROI measure conceptually related aspects of business success. It should be noted that, at Regimanuel Gray (Ghana) Ltd., the income attributed to a housing project is not METR-adjusted, but that the ROI is METR-adjusted. For this reason, it is salutary to measure both of these concepts in distinct research questions. Non-METR-adjusted income can still offer insight into the analogous contribution of low-cost housing projects to the growth of Regimanuel Gray (Ghana) Ltd., while ROI is an innumerably precise indicator of the profitability of low-cost-housing. The scrutiny of these variables represents an imperative contribution not inimitably to Ghanaian housing policy analysis, nonetheless also to Regimanuel Gray (Ghana) Ltd., which to date lacks an empirical antecedent on which to cognize the comparative profitability of its low-cost-housing endeavors across Ghana. The investigation to be carried out in this study could serve as the chief ingredient for a heterogeneous form of portfolio weighting that will allow Regimanuel Gray (Ghana) Ltd. to make better decisions about how to balance low-cost with non-low-cost housing projects.

Having presented a list of conscientiousness, a dialogue of theories, and an evaluation of some empirical literature and considerations, the next chapter of the study will consist of a report of findings―that is, the empirical blueprint itself.

3. Application of Theories to Real-Life Situation

3.1. Explanation of the Nature of the Problem and How It Was Solved

Three snags were disinterred in the study. First, it was conspicuous that Ghana’s housing market is not affordable for heavily populated lower-income Ghanaians, in contravention of the Government of Ghana’s goal of constructing an innumerable inexpensive housing market. Second, it was discovered that it is not conscious whether the Government of Ghana’s corporate income tax incentive for low-cost housing developers has been efficacious in heartening income for developers; as a result, the Government of Ghana does not have commensurable empirical aegis for deciding whether to carry forward or alter its corporate income tax incentive for low-cost housing developers. Third, it was descried that Regimanuel Gray (Ghana) Ltd. does not yet have an encyclopedic empirical crux on which to weigh low-cost versus non-low-cost housing projects in its portfolio.

The problems were deciphered by using statistical means to answer the following research questions and test their associated hypotheses:

RQ1: Is there a statistically significant association between the existence of Ghanaian corporate income tax incentives and income at Regimanuel Gray (Ghana) Ltd.?

H10: There is not a statistically significant association between the existence of Ghanaian corporate income tax incentives and income at Regimanuel Gray (Ghana) Ltd.

H1A: There is a statistically significant association between the existence of Ghanaian corporate income tax incentives and income at Regimanuel Gray (Ghana) Ltd.

RQ2: Is there a statistically significant difference between the 10-year profitability, calculated as return on investment (ROI), of all of Regimanuel Gray (Ghana) Ltd.’s low-cost housing projects and non-low-cost housing projects in Ghana?

H20: There is not a statistically significant difference between the 10-year profitability, calculated as ROI, of all of Regimanuel Gray (Ghana) Ltd.’s low-cost housing projects and non-low-cost housing projects in Ghana.

H2A: There is a statistically significant difference between the 10-year profitability, calculated as ROI, of all of Regimanuel Gray (Ghana) Ltd.’s low-cost housing projects and non-low-cost housing projects in Ghana.

3.2. Analysis of First Research Question

First, in order to test for interactions, low- and non-low-income housing income were correlated with each other. The correlation was established to be both sturdy (R = 0.7043) and substantial (p = 0.0230). Synergies were tested after the simple regression testing; however, in view of the p value of the synergy variable, at 0.902, was >0.05, it is not discussed in the analysis (Table 3).

Table 3. Regression of income attributable to low-cost housing and income attributable to non-low cost housing on total income.

Standard errors in parentheses. ***p < 0.01.

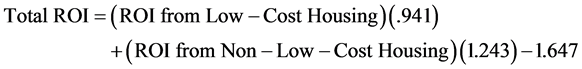

The resulting linear regression equation was as follows:

The R2 of the regression was 0.872, meaning that 87.2% of the variation in Regimanuel Gray’s income is associated with variation in income from low- and non-low-cost housing projects. The remaining 12.8% of variation is plausible correlated with factors such as currency fluctuations, investments, and other variables.

Note that only the p value affiliated with Non-Low-Cost Housing was statistically significant (<0.01). This discovery pinpoints that Regimanuel Gray’s low-cost housing; income does not induce a consequential contribution to the summative income generated by the corporation. In fact, when non-low-cost housing, income is regressed on total income, the resulting R2 is 0.8193, meaning that the addition of low-cost housing, income to the regression merely upsurges the predictive strength of the model by a few percent.

Subsequently, an independent samples t-test was carried out to determine whether there was a statistically significant difference amid the income contributed by low-cost housing and the income contributed by non-low- cost housing. It was recognized that there was a statistically significant (p < 0.01) difference amongst average income, average supplementary with low-income housing (M = $12,567,370, SD = 1,324,085) and w income concomitant with non-low-income housing (M = $139,639,000, SD = 6,095,264). Non-low-cost housing generated appreciable multitudinous income for Regimanuel Gray.

3.3. Analysis of the Second Research Question

First, in order to test for interactions, low- and non-low-income housing ROI were correlated with each other. The correlation was observed to be moderate (R = 0.6144), but not, at an Alpha of .05, significant (p = 0.0588). Interactions were therefore not calculated or tested for this research question.

Consequently, the returns on investment percentages of both low-cost and non-low-cost housing projects were regressed on total ROI for the company. The results follow (Table 4).

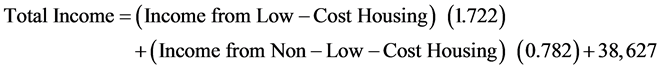

It was therefore detected that ROI obtained from non-low-cost housing was supplementary inclined to be associated with total company ROI than ROI obtained from low-cost housing. The resulting linear regression equation was as follows:

The R2 of the regression was 0.968, meaning that 96.8% of the variation in Regimanuel Gray’s ROI is associated with variation in ROI from low- and non-low-cost housing projects. The remaining 3.2% of variation is likely associated with factors such as currency fluctuations, investments, and other variables.

Table 4. Regression of ROI attributable to low-cost housing and ROI attributable to non-low cost housing on total ROI.

Standard errors in parentheses. ***p < 0.01.

Note that only the p value associated with Non-Low-Cost Housing was statistically significant (<0.01). This finding indicates that Regimanuel Gray’s low-cost housing ROI does not occasion a momentous contribution to the total ROI generated by the corporation. In fact, when non-low-cost housing ROI is regressed on total ROI, the resulting R2 is 0.9616, necessitating that the appendage of low-cost housing ROI to the regression does not burgeon the predicted intensity of the model.

Successively, an independent samples t-test was carried out to ascertain whether there was a statistically significant disparity amid the ROI contributed by low-cost housing and the ROI contributed by non-low-cost housing. It was realized that there was a statistically significant (p < 0.01) dissimilarity amongst run-of-the-mill ROI associated with low-income housing (M = 1.415, SD = 0.1721062) and mean ROI correlated with non- low-income housing (M = 15.948, SD = 1.226073). By this measurement, non-low-cost housing is slightly over 11 times countless profitable than low-cost housing.

3.4. Discussion of Results

Conceivably, the exceedingly pragmatic discovery in the study was that of ROI disparity amongst low- and non-low-cost housing ROI for Regimanuel Gray. Given that non-low-cost housing is slightly over 12 times myriad profitable, in terms of annual return on investment, then it can be deduced that the government of Ghana has not succeeded in utilizing tax policy to construct the construction of low-cost housing supplementary profitable for Regimanuel Gray. Not startlingly, the company’s total building volume, at least as measured by income derived, vestiges comprehensively weighted towards the non-low-cost segment. Moreover, the deficiency of a statistically significant correspondent among either of the ROI and income low- and non-low-cost variables connotes that Regimanuel’s non-low-cost business is not benefiting, either directly or indirectly, by taking on lower-income housing development work. The cardinal innuendo for the government of Ghana is that its 5-year tax holiday on low-cost housing developments is not efficacious, at least if the goal of this policy is to distort the market in the benignity of low-cost housing construction. The ramification for Regimanuel Gray is that prevalent pressure should be placed on the government in order to bring the profitability of low-cost housing projects closer to the profitability of non-low-cost housing projects, or Regimanuel Gray has no real incentive to remain profoundly involved in such projects.

3.5. Contribution of Study to Organization

One of the astronomical contributions to the organization was the juxtaposition of a hypothetically anticlimactic paradigm in taking on new-fangled low-cost housing project work without propagandizing for auxiliary tax breaks and multifarious incentives from the government of Ghana. Note that, over time, Regimanuel Gray has excogitated withal of its income from low-cost income housing projects, even as ROI for these projects has gone down. Regression analysis harbingered that Regimanuel Gray is snowballing low-cost housing, income by $1,073,175 per year, even though the ROI of such projects has been deteriorating at a rate of 1.4% a year. The fact that the income concomitant with low-cost housing projects is skyrocketing does not mean that low-cost housing projects are an economic boom for Regimanuel Gray, because income correlated with non-low-cost housing is spiraling at a considerably hair-trigger rate―approximately six times as fast, if the Beta coefficients of linear regression of year on low-cost income and non-low-cost income, respectively, are juxtaposed. In this scenario, it seems supplementary efficient for Regimanuel Gray to circumlocute as countless of its resources as conceivable unremitting from low-cost income housing projects and apply these funds to non-low-cost housing projects.

Of course, it is unlikely that Regimanuel Gray would pursue such a policy, as the company has reasons other than profit, including social service, to keep engaging in the building of low-cost housing projects. It might also be that engaging in low-cost construction somehow bolsters the Regimanuel Gray brand in a way that indirectly benefits the company as a whole, even though such interaction effect was observed in the two regressions performed in this study.

Nonetheless, what is of value for Regimanuel Gray is the generation of information that can be used to buttress the case that the government of Ghana needs to participate in a supplementary liberal tax concession policy vis-à-vis Regimanuel Gray, if not the Ghanaian construction industry as a whole. The purpose of tax breaks and related incentives is to make it more profitable for Sub-Saharan African construction companies engage in a form of production that is, at heat, inefficient. If efficiency is described as the ability to derive speculative profit from a similar investment of resources, then the ROI comparison between Regimanuel Gray’s low-cost housing projects and non-low-cost housing projects leaves little uncertainty that the company makes considerable money by creating buildings that opulent tenants can occupy. The government of Ghana is cognizant of this pecuniary dynamic, which is why the 5-year tax holiday for construction companies that build low-cost housing exists in the first place. However, if the tax holiday does not genuinely generate additional parity for companies such as Regimanuel Gray, then, over time, the companies will be conscripted by market pressures to abdicate the low- cost housing segment in the indulgence of supplementary lucrative economic opportunities.

Of course, game theory suggests that there is cooperation as well as competition between a government actor and a business actor, at least in a country with the semblance of a free market (Klemm & Van Parys, 2012). At one point, the government of Ghana was itself in the business of erecting low-cost housing, an endeavor that proved to be exorbitantly costly and not profitable enough for the government to sustain. The government therefore discontinued to compete in this market segment and began to cooperate instead with private firms, which, through subsidies such as tax breaks, were given incentives to engage more evocatively in the low-cost housing segment. Where game theory is particularly important is in specifying the kind of balance between cooperation and competition that currently exists between the governmental providers of subsidies and the private companies that act on such subsidies. The interest of government is to provide a subsidy that is just small enough to result in the kind of changed economic behavior that is sought by policy, while the interest of private business is to obtain the maximum subsidy from the government in exchange for changed economic behavior. The cardinal contribution of this study to Regimanuel Gray has been provision of information that the company, and conceivably others in the construction industry, can take back to the government of Ghana in order to demand greater subsidies associated with the building of low-cost housing projects. Given the vast disparity in ROI between low-cost and non-low-cost housing projects, Regimanuel Gray has an empirical basis on which to ask that the tax break be made deeper, or that other category of subsidies be introduced if the government of Ghana is serious about creating incentives for private companies to engage in the building of more low-cost housing projects.

Regrettably, the level of analysis provided in this study does not give Regimanuel Gray a specific figure that can be necessitated, whether in terms of a tax break or other compassionate of subsidy. Additionally, because the ROI of building is determined over multiple years (Greer & Kolbe, 2003), it cannot be expected that the effectiveness of any change that is indeed implemented by the government of Ghana will be glimpsed in the short term. It would unquestionably be supportive if there were empirical attested that a subsidy or tax break of a particular amount would escalate the ROI of Regimanuel Gray to a point at which it would be parsimoniously quick-witted for the company to keep consecrating its resources to low-cost housing work, but no such recommendation can be made on the basis of the work conducted in this study. Nonetheless, the study is invaluable in terms of having identified the failure of Ghanaian government policies to have shaped a state of affairs in which it is correspondingly profitable, or even close to correspondingly profitable, for Regimanuel Gray to mollycoddle in the construction of low-cost housing developments.

If Regimanuel Gray verves back to the bargaining table with the Ghanaian government on the axiom of the kind of data presented in this study, it will also be indispensable for the government to reevaluate its own policy goals. If the government tactility that there is still a prodigious transaction to be done in terms of generating an adequate base of low-cost housing for the country, then policy-makers will have to be supplemented contemplative about creating incentives that can make such construction as profitable as other kinds of construction. On the other hand, if the government tactility that the preliminary goals of the policy have been met or are close to being met, then there is not as considerable urgency to institute deeper subsidies or tax breaks. Whatever the case, it is strategically advantageous for Regimanuel Gray to be entered into these kinds of negotiations with empirical proof that low-cost housing is not, in spite of the current tax holiday, as frugally profitable as constructing buildings that can be occupied by middle- and upper-class tenants. Governments are not likely to change policies in courtesy of private sector actors unless a) those actors have some leverage (which, by virtue of its extensive construction resources and expertise in low-cost projects, Regimanuel Gray already possesses); and b) private sector actors can present government actors some proof that existing policies are inadequate. The most important contribution of this study to Regimanuel Gray was the provision of information that, in fact, the government of Ghana’s 5-year tax holiday for low-cost housing in Ghana is not effective, at least if effectiveness is measured as ROI. Under such circumstances, Regimanuel Gray can make a strong case for receiving further incentives to carry out additional low-cost construction in Ghana.

4. Lesson Learnt and Challenges

4.1. Lesson Learnt

The lessons learned from the current study can be approached from two theoretical perspectives, those of a) deploying government policy to change economic behavior and b) allowing market dynamics to dictate economic behavior. These theoretical perspectives have an ancient provenance; in the Politics, [28] Aristotle (2004) claimed that

It is clearly better that property should be private, but the use of it common; and the special business of the legislator is to create in men this benevolent disposition. Again, how immeasurably greater is the pleasure, when a man feels a thing to be his own; for surely the love of self is a feeling implanted by nature and not given in vain, although selfishness is rightly censured; this, however, is not the mere love of self, but the love of self in excess... (p. 25).

Aristotle was the first theorist explicitly suggesting that it is the job of government to nudge private economic actors to undertake actions on behalf of the public good. This idea remained relatively underdeveloped in the realms of policy and economics until the 19th and 20th centuries, when the maturation of neoclassical economics resulted in a more thorough examination of the relationship between private profit and the public good.

In The Economics of Welfare, the early 20th-century British economist [29] Arthur Pigou (2002) echoed Aristotle’s claim that benevolence (i.e. peacefulness) can emerge from economic arrangements overseen by the government. Pigou imagined a very specific intersection between economic policies and peace. To begin with, Pigou envisioned a distinct role for the state, which, importantly, he treated as distinct from the body of voters and the apparatus of government. For example, Pigou argued that “the State should protect the interests of the future in some degree against the effects of our irrational discounting and of our preference for ourselves over our descendants” (p. 29).

In the case of Ghana, the government is aware that the number of poor Ghanaians remains large, and, despite the success that Ghana has experienced in terms of reducing the number of people at the poverty gap, might increase once more. Therefore, the construction of low-cost housing is a means of addressing the future needs of Ghanaians that might go neglected in a market economy in which these Ghanaians cannot drive the economic behavior of developers such as Regimanuel Gray.

Pigouvian economic policy emerges as a kind of collective enterprise, one whose goal is not only to check external costs, but also to maximize external benefits of getting businesses to form co-operative pools in which “the profits of each member severally depend on the efficiency of all collectively” (2002, p. 341). Pigou envisions the state as the entity that can check costs by means of taxes and promote the benefits by subsidies, such as the 5-year tax break offered by the state of Ghana to companies erecting low-cost housing projects. Again, Pigou emphasizes the close link between economic policy and social policy when he states his presumption that “qualitative conclusions about the effect of an economic cause upon economic welfare will hold well also on the effect on total welfare” (p. 20). What happens in the economic sphere impacts the social sphere?

In terms of specific prescriptions, Pigou’s (2002) work suggests particular means by which government can go about the business of regulation. Pigou believed that such government-driven reallocation could often be wasteful, but, as a hedge, recommended that government weighs the costs and benefits of such reallocation upon each instance of the proposed regulation. As such, Pigou exhorts the government to act with sensitivity towards the current state of the market even as he sounds thematic notes that suggest an affinity to conservationism and socialism. It is this kind of balance that the state of Ghana has tried to strike by nudging companies such as Regimanuel Gray towards taking low-cost development actions that are not as profitable as high-cost development actions.

The theoretical perspectives of [30] Ronald Coase (1960) can also be used to understand Ghana’s attempt to influence the behavior of free market actors such as Regimanuel Gray. Coase’s article, “The Problem of Social Cost,” revolves around an example intended to demonstrate the primacy of cooperation in any rational framing of economic policy. Coase discusses the case of a cattle-breeder’s livestock wandering on to the nearby land of a farmer, where the herds of cattle destroy the crops. Coase argues that, while such a scenario would on any Pigouvian (2002) economic policy elicit fines and/or taxes for the cattle-breeder, a more efficient (and therefore rational) approach would be to recognize the reciprocal relationship between the two parties and to allow them to come to a market-based resolution to the problem, with government involvement limited to the drafting and oversight of laws intended to smooth such a transaction.

Both of these economic policy prescriptions were undeniably revolutionary. Coase (1960) urged reciprocal empathy for the cattle-breeder in his example, arguing that the breeder’s lack of access to the farmer’s land to fatten the cattle constituted a loss as economically tangible (albeit not as morally compelling) as the farmer’s loss of the crops. Meanwhile, in a Pigouvian (2002) scheme, the farmer would be recognized as the sole victim in the transaction, and would be compensated and/or protected accordingly. Coase thus revealed an implicit and instinctive trust in the marketplace that Pigou lacked; to revert to the intellectual terminology of the First World War, [31] Pigou (1916) had seen unchecked market activity as the god that failed, that in some way generated the masses of dead people and wrecked ideals and so moved him in the preface to his 1916 book. Coase’s attitude was far more optimistic, buoyed perhaps by the rising English GDP in his time (by contrast, GDP was flat from [32] 1925 to 1935, the period of Pigou’s greatest professional activity) and perhaps by a sunnier disposition than Pigou’s. As a result, Coase demonstrates a fine-tuned and unrelenting belief in markets, rationality, and cooperation that is missing from Pigou, and that forms the basis of Coase’s subsequent economic policy prescriptions.

In order to understand Coase’s (1960) applicability to the Ghanaian policy of tax breaks for companies such as Regimanuel Gray, it is necessary to first explore Coase’s work further. For example, Coase argues that “Satisfactory views on policy can only come from a patient study of how, in practice, the market, firms, and governments handle the problem of harmful effects” (p. 10). At first blush, this statement indicates that Coase is not in favor of a positive economic policy, at least insofar as policy is an activity that is framed by the government, but rather desires a policy of governmental absence of transactions. Indeed, writes Coase, “It is my belief that economists, and policy-makers generally, have tended to over-estimate the advantages, which come from governmental regulation” (p. 10).

Coase (1960) offers a fairly compelling example of his proposed policy-of-absence in action; by discussing the liability of British train operators (in the private epoch as well as in the era of nationalization). Apparently, in Britain, there was a law still current at Coase’s time of writing stating that non-negligent use of steam engines in trains cannot be penalized when it causes sparks and therefore leads to woods and other property burning down. Coase discusses this scenario in light of both his and Pigou’s (2002) theories of economic policy. Pigou, who settled upon this example himself, would have imposed some penalty on the train operators in order to compensate the owners of the woods for their losses. Coase takes a completely different approach―one in which, he, does not altogether rule out the role of government as a framer of economic policy, but in which he subordinates the role of the government to the role of the market.

Imagine, Coase (1960) says, that “running one train per day would enable the railway to perform services worth $150 per annum and running two trains a day would enable the railway to perform services worth $250 per annum” (p. 15). Now imagine that the cost of running one train a day is $60 in crop destruction, and the cost of running two trains a day is $120 in crop destruction; meanwhile the cost of running the train itself is $50 per annum for one train and $100 per annum for two trains. From this assumption, Coase enters into a discussion of a plausible scenario in which making the railroad company liable for fires would make it unprofitable to run any trains at all, and in which the growing of crops would not make up for the loss in economic services. Now, as Coase diligently points out, there are many underlying assumptions that could cause one to argue that it would result in more net economic activity to keep the train from running at all, but his point is merely to present a plausible scenario in which it is better to have the train run with no liability, because the economic activity generated by the train outweighs the value of the lost crops.