Advances in Sexual Medicine

Vol.4 No.3(2014), Article ID:47614,9 pages

DOI:10.4236/asm.2014.43007

Pattern, Types and Predictors of Contraception among Female In-School and Out-of-School Adolescents in Onitsha, Anambra State, Nigeria

Prosper Adogu1*, Ifeoma Udigwe1, Gerald Udigwe2, Achunam Nwabueze1, Chika Onwasigwe3

1Department of Community Medicine & PHC, Nnamdi Azikiwe University Teaching Hospital, Nnewi, Nigeria

2Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Nnamdi Azikiwe University Teaching Hospital, Nnewi, Nigeria

3Department of Community Medicine, University of Nigeria Teaching Hospital, Enugu, Nigeria

Email: *prosuperhealth@yahoo.com

Copyright © 2014 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received 2 May 2014; revised 2 June 2014; accepted 1 July 2014

ABSTRACT

Introduction: The consequences of unsafe sex are suffered mostly by adolescent girls in Nigeria despite efforts to improve accessibility to the reproductive and sexual health of this group. This study elucidates the pattern of contraceptive use, the key socio-demographic factors, sexual beliefs and practices associated with its use amongst adolescent girls in Nnewi, Nigeria. Methods: It was a descriptive cross-sectional comparative study of in-school and out-of-school female adolescents. Data were collected using questionnaires and Focus Group Discussion (FGD), then analyzed by selecting socio-demographic and other variables to assess their interaction with contraceptive use and result compared between the two groups. Data were presented in tables and charts and multivariate and chi-square analyses were performed. Result: Higher proportion of sexually active out-of-school girls than their in-school counterparts had ever used contraception—used it in their first and last sexual exposures, while condom was the commonest contraceptive employed by both groups. Age (older adolescents; F = 0.041), belief in condom use (P = 0.05), willingness to get condom for partner (P = 0.001) and regular sexual practice (P = 0.003) were the most important predictors of contraceptive use among the sexually active adolescents. Generally, the out-of-school girls are more likely to use contraceptives than their in-school counterparts. Some misconceptions about pregnancy prevention and unscientific contraceptive methods were mentioned by the subjects during the FGD. Recommendation: Access to reproductive health services needs to be improved especially among the in-school female adolescents. There is need to incorporate the right contraceptive information in the school curriculum, and the out-of-school adolescents should receive periodic dissemination of appropriate Behavior Change Communication (BCC) on the relevance of contraception.

Keywords: Pattern, Predictors, Contraception, Adolescents, Onitsha, Nigeria

1. Introduction

World Health Organization (WHO) estimates unsafe sex to be the second most important global risk factor to health [1] . Adolescents (10 - 19 years) especially females, are most vulnerable to unsafe sex. They also bear the brunt of the consequences. It is estimated that nearly two-thirds of premature deaths and one-third of the total disease burden in adults are associated with behavioral factors that began in youth and unprotected sex is mentioned among these factors [2] . Adolescence is a time when young people naturally explore and take risks in many aspects of their lives including sexual relationships. Comparative studies done between in-school and outof-school adolescents in some African countries have shown that out-of-school adolescents are more sexually active, have earlier sexual debut, lower contraceptive use and therefore suffer the consequences of unsafe sex more [3] -[5] . Also, comparative studies of the group have shown disparities. A study done in Tanzania and Ghana revealed that in-school adolescents initiated sex at lower age than the out-of-school adolescents and had lower contraceptive use [3] [6] . In contrast, a similar study carried out in Uganda reported that in-school adolescents had initiated sex at a later age and had higher contraceptive use than out-of-school adolescents [4] .

Non-use of condoms is common among adolescents; in Ghana and Uganda, up to two-thirds of adolescents who did not use condom at their sexual debut said that they felt safe with their partners [7] . This is similar to a survey done among Nigerian youth where 61% reported “trust in partner” as a reason for non-use of condom [8] . However, multiple sexual partnership, education, prior discussion on condom and one’s perception of the contact of HIV infection at single sexual contact reportedly increase the proportion of those who use condom [9] .

The government of Nigeria, its development partners, and international and local NGOs have been implementing vigorous activities to improve the use of contraceptives for many decades. Some progress may have been recorded especially in the area of knowledge, yet a large number of unmarried female adolescent Nigerians still have an unmet need for access to modern contraception.

This paper, therefore, aims to broaden the information base for the design of future family planning programmes by exploring some of the socio-demographic variables, sexual beliefs and practices that may be associated with contraceptive use by in-school and out-of-school unmarried adolescents aged 15 - 19 in Nigeria. The specific objectives of this study include:

1) To compare the pattern and types of modern contraceptive use between the in-school and out-of-school unmarried adolescents in Nnewi, Anambra State, Nigeria.

2) To ascertain and compare the factors influencing contraceptive use among the two groups.

2. Methods

Design and study area: A cross-sectional, comparative study of unmarried in-school and out-of-school female adolescents aged 10 - 19 years residing in Onitsha North LGA in Anambra State. The Onitsha main market enjoys large patronage by traders and visitors from Nigeria and environs. There are other surrounding satellite markets to relieve the enormous pressure on the main market. Out-of-school children are found in every part of the market hawking their wares. Some are in the market as shop assistants, while some are left entirely on their own in some stores. This scenario constitutes the setting for the out-of-school aspects of this study. Also the Onitsha North LGA has 25 private schools and 17 public schools, giving a total of 42 schools. They are 22 mixed schools, 12 boys’ only schools and 8 girls’ only schools. Some of the schools belong to the mission, some a government-owned, while the rest are private schools.

Study population: The study population consisted of unmarried female adolescents between the ages of 10 - 19 years and comprised: 1) in-school adolescents and 2) out-of-school adolescents. For in-school, only those in SSS1-SSS3 were considered for the study for comparison with their counterparts. This is because most of the out-of-school adolescents are within the age range of those in these classes than the classes below. For out-ofschool adolescents, those that have never been to secondary school, finished primary school but did not continue or had dropped out of secondary school were considered eligible. The exclusion criteria included, for in-school, all the post-secondary school adolescents, those with hearing, speech and mental disabilities were excluded; and for out-of-school, all adolescents who had finished secondary school or are in school and those with mental, hearing or speech disabilities were excluded.

Sampling technique: selection of in-school respondents: Secondary schools in the state were stratified into 4 categories as follows: 2 female-only private, 6 female-only public, 17 mixed private and 5 mixed public schools. From each of the strata, one school was selected using stratified random sampling technique. From each selected school, 100 respondents were selected using stratified random sampling ensuring representation from classes SSS1-SSS3, giving a total of 400 respondents, but response rate was however 97.8%.

Selection of out-of-school-adolescents: Unmarried female adolescents in the market were selected using cluster sampling technique as was done in a previous studies [4] [10] . The market is estimated to have more than 60 clusters. Clusters of 30 were selected by simple random sampling from the sampling frame containing the list of all the clusters twice [11] . Using the WHO cluster sampling method, 7 consenting adolescents were selected from each cluster until a total of 400 respondents was reached. Since the clusters were in different directions, a bottle was spinned and the direction of its mouth was used to show the starting point of the study.

Instruments/methods of data collection: The same pre-tested interviewer-administered questionnaires were used for both in-school and out-of-school adolescents to ensure uniformity. They were used to collect information on variables such as: demographic characteristics, pattern of sexual practices/behavior and outcome, and contraceptive use.

Data analysis: SPSS version 17 statistical software was used for data entry and analysis. The Chi(X2) square statistical test was used to compare proportions and evaluate associations and t-test for quantitative variables. Differences and associations yielding p values of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant (p ≤ 0.05).

3. Result

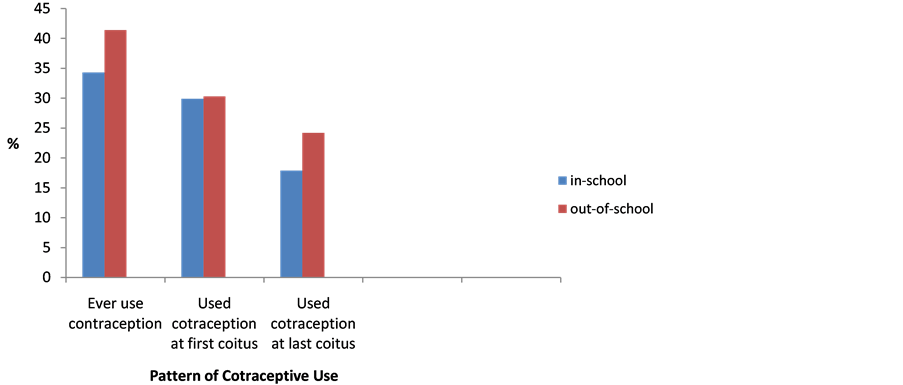

Figure 1 shows that only 23 (34.3%) out of 67 in-school girls and 41 (41.4%) out of 99 out-of-school girls had ever used contraception despite being sexually exposed. About 30% of them in both groups used condom at first sex. However, even a fewer proportion 17.9% of in-school girls and 24.2% of out-of-school girls had used contraception at their last sex.

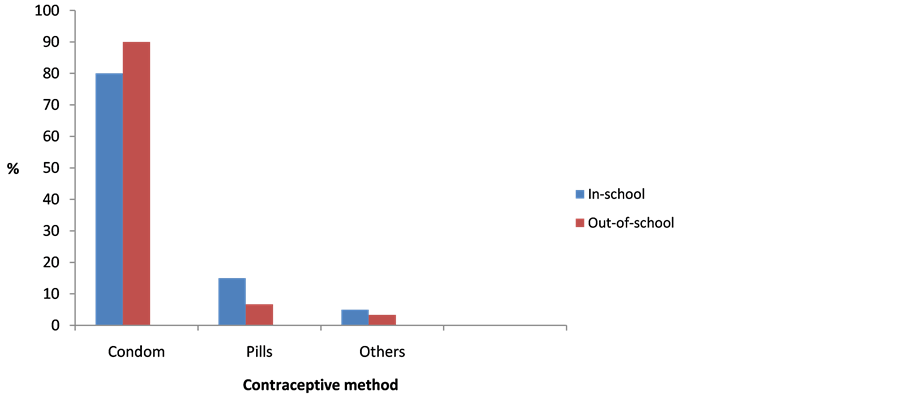

Figure 2 clearly indicates that condom was the most common contraception used at first sex in both groups of adolescents.

Figure 1. Pattern of contraceptive use by in-school and out-of-school adolescents who had ever had sex.

Figure 2. Method of contraception used at first coitus.

In Table 1, 67 (16.8%) out of 400 in-school adolescents and 99 (24.8%) of the 400 out-of-school adolescents were sexually active. In both groups, statistically significant association was found between use of contraception and age in the sense that contraceptive use significantly increased with age of the adolescents (p = 0.041).

Table 2 shows that the belief by respondents that single couples should use condom during premarital sex (p = 0.05), willingness to get condom for partners (p = 0.001) and the practice of regular engagement in sex (p = 0.003) all significantly predict the use of contraceptives among the adolescents.

4. Focus Group Discussion (FGD) Result

Preventive measures taken by young people against HIV/STI and unwanted pregnancy:

Majority mentioned totally avoiding sex (abstinence), use of condom, staying faithful to one partner and avoiding use of contaminated sharp instrument as measures taken to avoid the consequences of unsafe sexual intercourse. However, a 15 year old out-of-school discussant said “If you fear God, you will not have sex, and you will not get pregnant or HIV”. Another said: “Some of my friends take very strong local concoctions after sex to avoid getting pregnant, and it works.” An in-school adolescent mentioned that sometimes they wash their private parts with strong soap after having sex.

Reasons for low contraceptive usage among adolescents:

Both in-school and out-of-school participants frowned at encouraging the use of condoms. Majority believe it encourages sexual promiscuity among the youth. In addition, most also attributed their non-use of it to fear of side effects as one of the discussants puts it; “We were told contraception damages a woman’s womb”. Another said “People will hate the girl, if they see her buying condom”.

5. Discussion

Only one in four of the respondents had ever used contraception, one in three at their first sexual exposure and one in five at their last sexual intercourse. This is comparable to the figure from studies reported from northern Nigeria (24%) [12] of last use of contraception, Ibadan (32.2%) [13] of first use and Ilorin (25.4%) [14] of ever use of contraception. However, this is higher than the figures from the 2008 National Demographic and Health Survey (NDHS) where 17.3% and 39.4% of youth from Anambra state used contraception at their first and last sexual intercourse respectively [15] . In this study, there was no significant difference in contraceptive use, though out-of-school adolescent had a higher percentage usage. The result is in contrast to other studies done in Ghana [3] and Uganda [4] where in-school adolescents significantly used contraceptives more than out-ofschool adolescents, and the 2008 NDHS report that increased condom or contraceptive use is associated with increasing level of education [15] . The reason for the low level of contraceptive use in both groups could be, because majority of them are Roman Catholics a faith that discourages artificial contraception and emphasizes abstinence.

Table 1. Relationship between contraceptive use and socio demographic variables of the girls.

n = number per age group that use contraceptive; n = number per age group sexually active.

Table 2. Relationship between contraceptive use and some sexual beliefs and practices among the girls.

Major reasons for non-use of contraception among the sexually active in-school adolescents were that they did not think of it (31.8%), fear (17.5%) and the feeling of embarrassment in buying one (20.6%). While the reasons out-of-school girls gave were fear of side effects (26%), did not think of using one (14.6%) and refusal by partner (9.4%). This is in contrast to studies done in Owerri [16] and Ilorin [17] where a higher proportion of adolescents (43.5%) and (77.5%) expressed fear as the major reason for not using any contraception. Fear was the major reason pointed out during the focused group discussions. Female adolescents may not insist on condom use because they may be afraid of losing their lovers, or the source of their monetary support. Also, some fear that the use of contraception could render them infertile. In another African country, the major reason was that they felt safe with their partners [7] .

Culture and religious belief seem to influence the contraceptive use among the adolescents in Nigeria. Even though this study has shown that condom was the commonest method of contraception used by both groups and this is similar to finding from many studies [7] [15] [18] [19] , yet numerous other studies have found that young people’s perceptions of condoms tend to be negative [14] [20] [21] . and such youths in Sub-Saharan Africa still engage in risky sexual behavior. Studies have also documented that young people have concerns about condom safety and breakage, condom ineffectiveness, the negative effect of condom use on sexual enjoyment, the low quality of condoms especially those that are free and condom use signifying infidelity or having an STI [20] - [23] . The above results/findings call for a well-organized information, education and communication through peers to bring about behavioral change.

Twenty-two percent of the in-school girls have ever been pregnant compared to 43.4% of their out-of-school counterparts and this was statistically significant. This is higher than in a study carried out among female adolescents in Port Harcourt where unintended pregnancy among adolescents was 78.8% prevalence [24] , Owerri 31.6% and 78.9% recurrence [25] , while a study in the north-central part of Nigeria reported the prevalence of only 5.1% [26] . The variation in prevalence could be due to different cultures and industrialization in different parts of the country, most in the north-central believe in early marriage for their teens and therefore the incidence of teenage pregnancy will be low in such places.

Unplanned pregnancies are the result of various factors, including poverty, early sexual debut, a lack of knowledge about menstruation and pregnancy, a lack of access to, and knowledge about how to use contraceptives, difficulties in using contraceptives because of a partner’s or family objections; contraceptive failure; and sexual assault [27] . A study carried out among adolescents in Congo, identified factors such as unemployed mothers, early puberty, non-sex education and being out-of-school; as major risk factors to adolescent pregnancy rates [28] . Other important factors increasing the prevalence of unintended pregnancy among adolescents are early sexual debut and coerced sex. In most studies, including NDHS 2008, early sexual debut and coerced sex were more prevalent in those with low education status, is associated with increasing level of teenage pregnancy among out-of-school adolescents compared to those in school. Most studies conducted amongst adolescents reported that termination of schooling is associated with unintended pregnancy among students. A recent study in Nigeria reported that 43% discontinued schooling [29] and in Congo, up to 82.4% of adolescents gave up schooling [28] .

Adolescent mothers may pass on to their children, a legacy of poor health, substandard education and subsistence living, creating a cycle of poverty that is hard to break [30] . Several studies have shown that some victims of unintended pregnancy were more likely to be children of mothers with limited school education and history of unintended teenage pregnancies. In Nigeria sex out of wedlock is stigmatized and pregnancies bring disgrace to the young girl and her family. Most adolescents are aware that sexual activity puts them at risk of getting pregnant or contacting HIV and in spite of that many still engage in risky sexual behaviour. Eighty percent of inschool adolescents in this study have ever had an abortion compared to 69.8% of the out-of-school adolescents. It is similar to the prevalence in Nigeria, where 60% of all abortions are attributed to adolescents [31] . Another study in Nigeria reported as much as 100% prevalence of those who ever got pregnant [32] , while another study reported a lower prevalence of 20.2% [28] .

6. Recommendations

In the short to medium term, it is recommended that the government and its partners should encourage outreach services especially for in-school adolescents, whilst improving the capacity of health service providers to deliver adolescent friendly services. In the long term they should go beyond increasing the availability of health facilities, to improve the privacy in the reproductive health section of these facilities. For all adolescents with unmet need for contraception, access to youth-friendly contraceptive services is vital in order to strengthen their sexual and reproductive health and rights and reduce risks for HIV infection and unwanted pregnancy. Out-of-school adolescents should also be targeted to go through Behavioral Change Communication (BCC) on the importance of contraception. Using the findings of the study as baseline data, the ministry of health and education, faith organization, international and non-governmental bodies and all adolescent stakeholders should collaborate and cooperate with opinion leaders to impact and improve the contraceptive consciousness of the out-of-school adolescents.

Majority of adolescents still abstain from sex, even in the study area which is dominated by Roman Catholics who do not believe in contraception and emphasize sexual abstinence to the youth and adolescents. Therefore more research on sexual abstinence should be carried out to determine the factors influencing it in young people, and probably such factors can be used as a model for sexuality education among the adolescents. Further research is also essential to explore the trends in contraceptive use among male adolescents.

Conflict of Interest

None declared by the authors who have all substantially contributed to the research and manuscript.

Acknowledgements

This report is part of the dissertation presented and successfully defended at the Nigerian National Postgraduate Medical College, Faculty of Public Health in April 2012 part two final examinations.

Ethical Consideration and Permission

Ethical clearance was secured from the Ethics Committee of the Nnamdi Azikiwe University Teaching Hospital Nnewi. Official permission was also obtained from Anambra State Education Commission, Onitsha North Local Government authorities, each selected school authority and the authorities in charge of the market. Informed consents were obtained from the adolescents’ parent/guardian especially for out-of-school respondents and from all respondents after explaining the purpose, objectives and benefits of the research to them. They were assured of no harm in participation and were told that participation is entirely voluntary.

References

- World Health Organization (2004) Reproductive Health Strategy. WHO, Geneva.

- World Health Organization (2008) 10 Facts on Adolescent Health. WHO, Geneva.

- Sallah, A.M. (2009) Sexual Behaviour and Attitude towards Condoms among Unmarried in School and Out-of-School Adolescents in a High HIV Prevalence Region in Ghana. International Quarterly of Community Health Education, 29, 167-181.

- Kipp, W., Diesfeld, H. and Ndyanabangi, B. (2004) Reproductive Health Behaviour among In-School and Out-ofSchool Youths in Kabarole District, Uganda. African Journal of Reproductive Health, 8, 55-57.http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/3583393

- Batwala, V., Nuwaha, E., Mulogo, E., Bagenda, F., Bajunirwe, F. and Mirembe, J. (2006) Contraceptive Use among In-School and Out-of-School Adolescents in Rural South-West Uganda. East African Medical Journal, 83, 18-24.http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/eamj.v83i1.9356

- Kazaura, R. and Melkiory, C. (2009) Sexual Practices among Unmarried Adolescents in Tanzania. BMC Public Health, 9, 373. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-9-373

- Alan Guttmacher Institute (2006) Adolescents in Ghana. Alan Guttmacher Institute, New York.

- Durojaiye, C.O. (2009) Knowledge, Perception and Behavior of Nigerian Youth on HIV/AIDS. Internet Journal of Health, 9, 1.

- Adebiyi, A.O. and Asuzu, M.C. (2009) Condom Use amongst Out-of-School Youth in a Local Government Area in Nigeria. African Health Sciences, 9, 92-97.

- National Population Commission (NPC) and ICF Macro (2009) Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey 2008. National Population Commission and ICF Macro, Abuja.

- Rosneo, B. (1995) Fundamentals of Biostatistics. 4th Edition, Wadsworth, Belmont.

- Ajuwon, A.J., Olaleye, A., Faromoju, B. and Ladipo, O. (2006) Sexual Behavior and Experience in Three States in North Eastern Nigeria. BMC Public Health, 6, 310. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-6-310

- Adeyinka, D.A., Oladimeji, O. and Adeyinka, E.F. (2009) Contraceptive Knowledge and Practices: A Survey of Undergraduates in Ibadan Nigeria. International Journal of Adolescent Medicine and Health, 3, 465-411.

- Abiodun, O.M. and Balogun, O.R. (2009) Sexual Activity and Contraception Use among Young Female Students of Tertiary Institutions in Ilorin, Nigeria. Contraception, 79, 146-149. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.contraception.2008.08.002

- National Population Commission (NPC) and ICF Macro (2009) Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey 2008. National Population Commission and ICF Macro, Abuja.

- Okereke, C.I. (2010) Sexually Transmitted Infections among Adolescents in a Rural Nigeria. Indian Journal of Social Work, 7, 32-40.

- Abiodun, O.M. and Balogun, O.R. (2009) Sexual Activity and Contraception Use among Young Female Students of Tertiary Institutions in Ilorin, Nigeria. Contraception, 79, 146-149. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.contraception.2008.08.002

- Odeyemi, K., Onajole, A. and Ogunnowo, B. (2009) Sexual Behaviour and the Influencing Factors among Out-of-School Females Adolescent in Mushin Market, Lagos Nigeria. International Journal of Adolescent Medicine and Health, 21, 101-109. http://dx.doi.org/10.1515/IJAMH.2009.21.1.101

- Moronkole, O.A. and Fakeye, J.A. (2007-2008) Reproductive Health Knowledge, Sexual Partners, Contraceptive Use and Motives for Premarital Sex among Females Sub-Urban Nigerian Secondary Students. International Quarterly of Community Health Education, 28, 229-239.

- Bankole, A., Ahmed, F.H., Neema, S., Quedraogo, C. and Kongoni, S. (2007) Knowledge of Correct Condom Use and Consistency of Use among Adolescent in Four Countries in Sub-Saharan Africa. African Journal of Reproductive Health, 11, 197-220.

- Guiella, G. and Madise, N.J. (2007) HIV/AIDS and Sexual Risk Behavior among Adolescents: Factors Influencing Use of Condoms in Burkina Fasso. African Journal of Reproductive Health, 11, 182-196. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/25549739

- Meekers, D., Ahmed, G. and Molatlhegi, M.T. (2001) Understanding Constraints to Adolescents Condom Procurement: The Case of Urban Botswana. AIDS Care, 13, 297-302. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09540120120043946

- Onayade, A.A., Abiona, T.C., Ugbala, C., Alozie, G. and Adetugi, O. (2008) Determinants of Consistent Condom Use among Adolescents and Young Adults Attending a Tertiary Education Institution in Ile-Ife, Nigeria. Nigerian Postgraduate Medical Journal, 15, 185-191.

- Okpani, A.O. and Okpani, J.U. (2000) Sexual Activity and Contraceptive Use among Female Adolescents: A Report from Port-Harcourt, Nigeria. African Journal of Reproductive Health, 4, 40-47. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/3583241

- Okereke, C.I. (2010) Unmet Reproductive Health Needs. Health Seeking Behaviour of Adolescents in Owerri, Nigeria. African Journal of Reproductive Health, 14, 43-54.

- Adekunle, L.A., Ricketts, O.Z., Ajunwon, A.J. and Ladipo, O.A. (2009) Sexual and Reproductive Health Knowledge, Behavior and Education Needs of in-School Adolescents in Northern Nigeria. African Journal of Reproductive Health, 13, 37-39.

- Bryan, D. and Packer, M.S. (2004) Adolescents, Unwanted Pregnancy and Abortion. Ipas, Chapel Hill.

- Mabiala, J.R., Massamba, A., Bantsima, T. and Senga, P. (2008) Sexual Behaviour among Adolescent in Brazzaville, Congo. Journal de Gynécologie, Obstétrique et Biologie de la Reproduction, 37, 510-515.

- Onyeka, I.N., MieHola, J., Ilika, A.L. and Vaskilampi, T. (2011) Unintended Pregnancy and Termination of Studies among Students in Anambra State, Nigeria. African Journal of Reproductive Health, 15, 109-115.

- World Health Organization (2008) Adolescent Pregnant-Unmet Needs Undone Deeds. WHO, Geneva.

- Federal Ministry of Health (2009) Assessment Report of the National Responses to Young People’s Sexual and Reproductive Health in Nigeria. Abuja.

- Aderibigbe, S.A. and Araoye, M.O. (2008) Effect of Health Education on Sexual Behaviour of Students of Public Secondary Schools in llorin, Nigeria. European Journal of Scientific Research, 24, 33-41.

NOTES

*Corresponding author.