Advances in Sexual Medicine

Vol. 3 No. 3 (2013) , Article ID: 34135 , 13 pages DOI:10.4236/asm.2013.33009

Menopausal Perceptions and Experiences of Older Women from Selected Sites in Botswana

1Department of Statistics, University of Botswana, Gaborone, Botswana

2Department of Population Studies, University of Botswana, Gaborone, Botswana

Email: amano@mopipi.ub.bw, ngome@mopipi.ub.bw

Copyright © 2013 Njoku Ola Ama, Enock Ngome. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Received April 8, 2013; revised May 8, 2013; accepted May 16, 2013

Keywords: Older Women; Menopause; Knowledge; Perceptions; Logistic Regression; Factor Analysis

ABSTRACT

Objective: To assess the menopausal perceptions and experiences of older women from selected sites in Botswana. Design: This study used snowball sampling to recruit 444 older women in four health districts of Botswana. Trained research assistants administered a structured questionnaire to determine respondents’ menopausal symptoms, perceptions and knowledge of menopause and sexual experiences. Multiple logistic regression procedures were used to evaluate the association of socio-demographic characteristics with knowledge of menopause and factor analysis was used to cluster menopausal symptoms. Results: Participants had low levels of knowledge and awareness of menopause. The three most common changes identified were weakening of bones (78%), changes in sex drive (69.6%), and difficulty working (56.2%). The majority of respondents perceived menopause as freedom from menstrual cycles (85%) and cost saving (65%). Employment status was significantly associated with knowledge of menopause. The mean age at menopause was 48.9 years. With an average life expectancy of 54.5 years, there remains about 6 years of postmenopausal life. Recommendation: Public health care systems in and beyond Botswana should mobilize resources and take measures to improve older women’s awareness and knowledge about menopause-related changes through educational training and guidance to maintain active, healthy lives.

1. Introduction

This study investigates the perceptions, knowledge and experiences of menopause among a sample of older women in order to understand the supports and services they need. A cross-sectional survey was conducted using in-depth interviews with women aged 50 years and over in four districts (two rural and two urban) of Botswana. The results are presented in terms of five study objectives, namely, socio-demographic characteristics, perceptions and knowledge of menopause, factors affecting knowledge of menopause, patterns and clustering of experiences of menopause, and pre-and post-menopausal sexual experiences.

1.1. Background and Literature Review

Menopause is a process which typically occurs during the ages of 45 and 55 and is marked by a reduction in estrogen and progesterone levels and eventual cessation of menstruation [1]. The process is deemed complete after one year without menstruating. During the transitional, or perimenopausal period, women may experience symptoms which include: reduced frequency prior to cessation of menstrual periods, when pregnancy is still possible); heart pounding or racing; hot flashes, with intense warmth, flushing and perspiration, usually worst in the first 1 - 2 years; night sweats; skin flushing; sleeping problems, including insomnia; decreased interest in sex and possibly decreased response to sexual stimulation; forgetfulness; headaches; mood swings including irritability, depression, and anxiety; urine leakage; vaginal dryness and painful sexual intercourse with thinning and loss of elasticity in the vaginal wall; vaginal infections; joint aches and pains and irregular heartbeat (palpitations) [1,2].

The transitional phase of menopause is classified by [3,4] as Stage −2 (early) and Stage −1 (late) and the postmenopausal phase as Stages +1 (early) and +2 (late). Stage −2 usually involves variable menstrual cycle length and increased levels of follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and low antimullerian hormone (AMH) and antral follicle count (AFC). Stage −1 is characterized by the onset of skipped cycles or amenorrhea of at least 60 days and continued elevation of FSH [3]. Late transition is marked by the occurrence of amenorrhea of 60 days or longer, more variable cycle length, extreme hormonal fluctuations and increased prevalence of anovulation (late) [3].

Most women do not need treatment of menopausal symptoms. It is either the symptoms resolve on their own or their level is tolerable [5,6]. The treatments, when needed, include medications and lifestyle changes. Hormone replacement therapy (HRT) or hormone therapy (HT) helps to diminish symptoms such as vaginal dryness, itching, and discomfort, urinary problems, bonedensity loss, hot flashes and night sweats. However, HRT has risks as well as benefits. Other treatments include: Low-dose oral contraceptives to help stop or reduce hot flashes, vaginal dryness, and moodiness and either overthe-counter or prescription remedies for vaginal discomfort, such as estrogen creams, tablets, or vaginal rings [5,6].

A study by [7] has shown that factors such as attitude, diet, overall health, genetics and cultural beliefs affect women’s experiences with menopause. Although it is a universal midlife transition for women, many aspects of menopause remain poorly understood. It was acknowledged by [8] that menopause is multidimensional and is influenced by biological, psychological and sociocultural factors and that the process requires responses that are equally multidimensional. Attitude towards menopause may influence the experience [9-11] and how a woman views herself in midlife [12,13], particularly when social norms about youth and beauty drive one’s sense of sexuality and self-esteem [2,14,15].

A study by [16] showed regional and cultural differences in expectations about menopause. For instance, while women in Germany might experience more hot flushes, in Papua New Guinea there is significantly higher intensity in areas of cardiac trouble, low sex drive, urological symptoms, vaginal dryness, joint and muscle symptoms [16]. A study by [17] showed that previous hysterectomy, history of smoking and alcohol intake predicted whether or not women had ever had hot flushes/ night sweats. Moreover, anxiety, hysterectomy, depressed mood, years since last menstrual period and (less) education predicted current hot flushes/night sweats.

In sum, while menopause is a natural and universal phenomenon for women at mid-life, the process is variable and it depends on a range of biological, psychological, social and cultural factors [18]. For many, it is a relatively neutral process, though women in Western countries tend to report more symptoms. To respond effectively to menopause-related health, mental health and social needs require a better understanding of the sources of these variations and their outcomes. The purpose of this study is to assess the level and variability of knowledge which older women have about menopause and to determine which factors, in addition to age [17] that contribute to this variability.

1.2. Justification for the Study

Botswana is one of few African countries with well-developed medical care, including hospitals and clinics within 15 kilometres from any community. Yet older women have limited awareness of programmes and interventions to address their sexual and reproductive health (SRH) and it is unclear how well health services meet these needs, including needs related to menopause [19]. But older women’s SRH needs are critical to geriatric and family healthcare, particularly with respect to HIV/AIDS, as they provide the majority of care to children who are orphaned and vulnerable due to this disease. There is very little in the way of patient or public education about menopause within or beyond health care facilities, although this type of information is crucial to improving the older women’s health and quality of life. The contribution of the present study is thus timely for health policy-makers, program developers and practitioners.

An estimated 45% of older women aged 50 - 59, 31% of those aged 60 - 69 years and 11% of those aged 70 - 79 years still enjoy sex with their partners [19]. Sexually active women are vulnerable to HIV transmission due to vaginal dryness and not using condoms for birth control. Health professionals should be aware of these and other menopause-related risks so that they can facilitate informed decision-making about effective modes of prevention and intervention [18]. Data for this paper originated in a parent study by [19] conducted between February and October 2011. Results of the analyses will be useful for promoting awareness of menopausal problems experienced by older women among public healthcare providers and policy makers in Botswana.

The paper has five aims, as follows:

1) To describe the socio-demographic characteristics of older women in the study sample.

2) To assess study participants’ perceptions and knowledge of menopause and their attitudes about sex and sexual activity.

3) To determine how socio-demographic factors influence knowledge of menopause 4) To determine the patterns and clustering of the older women’s health experiences.

5) To explore study participants’ preand post-menpausal experiences.

2. Methods

The aforementioned parent study from which this paper derives covered four health districts in Botswana: Gaborone (urban), Kweneng East (rural), Selibe Phikwe (urban) and Barolong (rural). In 2011, women aged 50 years and over [20] numbered 139,915, representing 15.2% of the total female population and 12.1% of the country’s population. The sample size was determined using an online programme [21]. This statistical package allows one to set the desired confidence interval and allowable error margin in order to determine a sample size that will attain maximum power. With a 95% confidence interval and an error margin of 5%, the sample size required for the study was 454. This number was allocated to the four districts using probability proportional to size (PPS), where the size is the number of older women from each district [16] (see Table 1). The snowball technique, a non-probability sampling method was then used to identify eligible participants from each district. This strategy was used because the population is sparse and diffuse and there was no current sampling frame of older women. Snowball sampling may be used when the desired sample characteristic is rare, i e., when it is extremely difficult or cost prohibitive to locate respondents in a study population [22,23]. This technique involved first identifying a key informant in the district. The informant then identified a first subject, who provided the name of a second subject, who provided the name of a third, and so on [23-25].

Due to difficulty in achieving the proposed sample size in Barolong (a predominantly rural population dispersed over a large geographical area), we slightly oversampled in Selibe Phikwe (an urban area) and Kweneng East (a rural area).

2.1. Instrumentation and Data Collection

The study questionnaire included questions on sociodemographic characteristics, age at menopause, perceptions of menopause, adverse effects of menopause, experiences before and after menopause, and attitudes about sex. Some of the questions were open-ended to give the respondents a chance to give further clarification on some of the issues addressed in the questionnaire. The instrument was constructed based on available literature and was pretested for validity, quality, clarity and content before being used for the main study. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of reliability (or consistency) was calculated as 0.89.

Research Assistants completed a two-day training workshop which covered the purpose of the study, IRB training, the contents and administration of the questionnaires. Data were collected through in-person interviews in respondents’ homes or workplace depending on their preference. Research assistants explained the purpose of the study and obtained informed consent. No personal identifiers were attached to the questionnaire. A total of 444 older women completed the interview, with a small number of refusals. The response rate of 98% was much higher than that obtained in a similar study [24].

2.1.1. Ethical Considerations

The instrument was reviewed by experts in public health and ageing for quality, clarity and content in addressing the objectives of the study. It was then approved by the University of Botswana Institutional Review Board (IRB), the Ministry of Health Research and Ethical Committee and the District Health Management Teams in each of the study health districts.

2.1.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria for Subjects

Only Batswana women aged 50 years and over, and who were able to provide informed consent were included in the study. Non-Batswana older women were excluded.

2.2. Analysis

Data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 20. All variables, including responses to open-ended questions, were coded before entry. Descriptive measures, such as percentages and correlation are presented along with graphics that further illustrate the results. Multiple logistic regression analysis was used to explore socio-demographic factors affecting women’s knowledge related to menopause. Principal components factor analysis was used to explore the clustering of menopausal symptoms [26,27].

3. Results

3.1. Socio-Demographic Characteristics

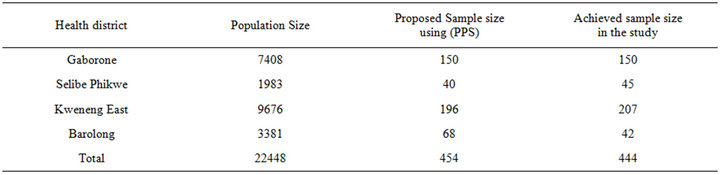

Figure 1 presents socio-demographic characteristics of the sample. Over half of women in the study were aged 50 - 59; 27% were 60 to 69 and 13.5% were 70 to 79. About 1% was aged 90 or older. A substantial proportion (42.8%) had no formal schooling while 57.2% had some education. Just under one third of the sample was employed. About one-third were married while 27.9% were never married; 24.1% were widowed, 6.3% were cohabitating and 8.6% were divorced.

3.1.1. Age at Menopause

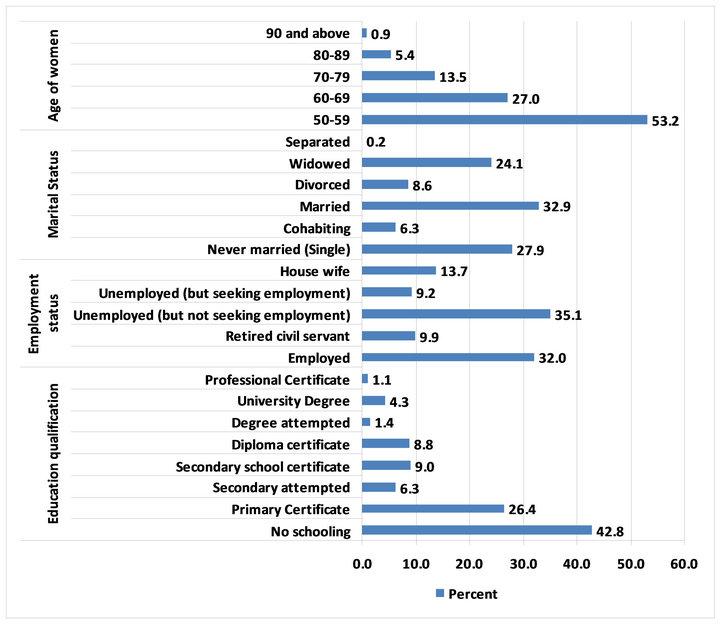

Almost half of respondents reached menopause between age 41 and 50 years, as did just a quarter between ages 51 and 60 years. Small numbers of women attained menopause between ages 31 and 40 years (5.2%) or at age 61 or later (0.7%) (Figure 2). One in five women reported that they could not remember the time of menopause.

The mean age at menopause was 48.9 years, about the same as the median and modal age of 50 years. The average life expectancy of females in Botswana is currently

Table 1. Sample allocation of the study sample to the districts.

Figure 1. Socio-demographic characteristics (N = 444).

54.51 years (see http://www.indexmundi.com/Botswana/life_expectancy_at_birth.html), meaning that women who survive to age 50 will, on average, live another 5.61 years after menopause.

3.1.2. Perception of Menopause

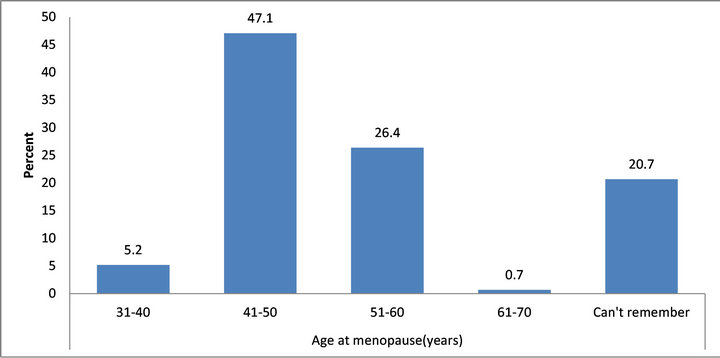

The majority of older women (85%) perceived menopause as being free from menstruation. 68% saw themselves as more relaxed and 65% reported it as cost saving because they do not have to purchase sanitary supplies any longer. While 54% of the older women saw menopause as heralding medical problems that required interventions, 53% viewed it as a positive development in their lives (Figure 3).

3.1.3. Knowledge of Menopause

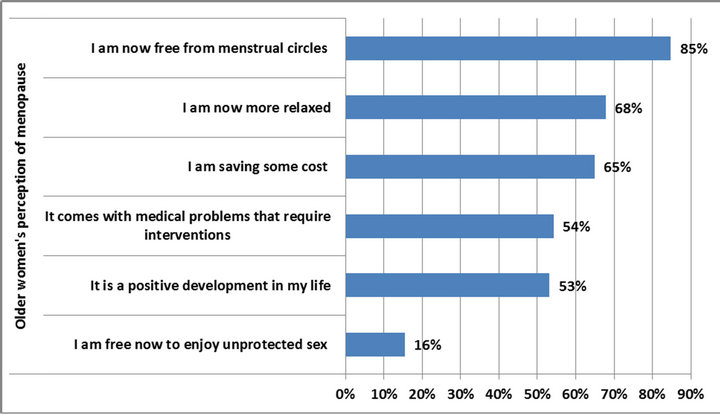

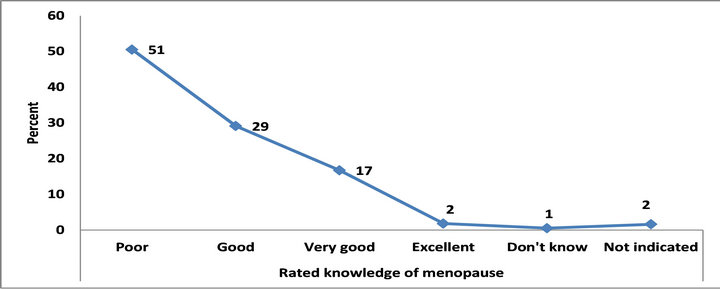

Study participants were asked to rate their knowledge of menopause, including symptoms and treatment. A little over half (51%) indicated that they had poor knowledge of menopause, while the balance reported their knowledge of menopause was good (29%), very good (17%) or excellent (2%) (Figure 4).

3.2. Socio-Demographic Impact on Knowledge of Menopause

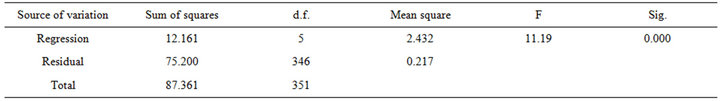

Sociocultural background, educational attainment, physical and emotional health is known to affect women’s knowledge and beliefs about menopause. Multiple logistic regression analysis of knowledge of menopause (1 = any knowledge; 0 = no knowledge) with socio-demographics shows that the joint effect of the respondents’ place of origin, marital status, age at menopause, educational status and employment status is significantly associated with knowledge of menopause (p < 0.001) (Table 2). However, these variables account for only 6.3% of the variation in knowledge.

As seen in Table 3, older women in urban areas were 2.8 times more likely to have knowledge of menopause than those from rural areas, while employed women and those with some education were 3.2 times and 2.4 times more likely, respectively, to have such knowledge than those who were unemployed and those who lacked education. Older women who reached menopause at age 50 years or older were less likely (OR = 0.74) to have better knowledge than those who experienced menopause at 50 years and below. Similarly being married does not improve knowledge as the married women are less likely. (OR = 0.48) to have better knowledge of menopause (Table 3).

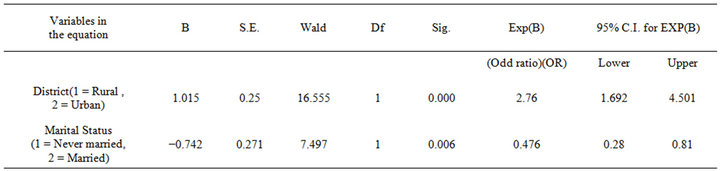

Most older women (69.6%) were aware that menopause knowledge of how this happens (e.g., effects on bones) was inadequate (Figure 5).

Figure 2. Age at menopause (N = 352).

Figure 3. Perceptions of menopause (N = 374).

Figure 4. Self-rating of knowledge of menopause (N = 444).

Table 2. Logistic regression of sociodemographic characteristics on knowledge of menopause. ANOVA Table.

Table 3. Impact of socio-demographic variables on knowledge of menopause (N = 444).

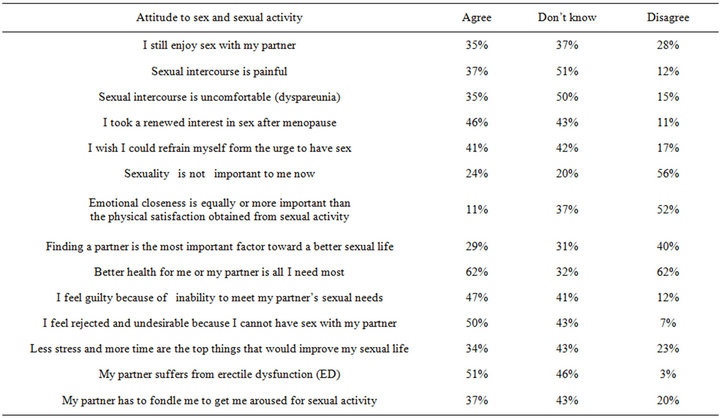

3.2.1. Attitudes toward Sex and Sexual Activity

Some preand post-menopausal women experience decreased interest in sex, and possibly decreased response to sexual stimulation. Study participants were queried about their general attitude toward sex and sexual activity (1 = Agree; 2 = Don’t know and 3 = Disagree). As seen in Table 4, 35% still enjoy sex with their partners while just over one-third (37%) report that sexual activity is painful or uncomfortable. About 41% expressed a desire to refrain themselves from the urge to have sex and 51% felt rejected and undesirable because they could not have sex with their partners. Most women (62%) reported that better health for them and their partners are all they need while others (52%) mostly valued emotional closeness rather than the physical satisfaction from sexual activity. Almost half (46%) took a renewed interest in sex after menopause.

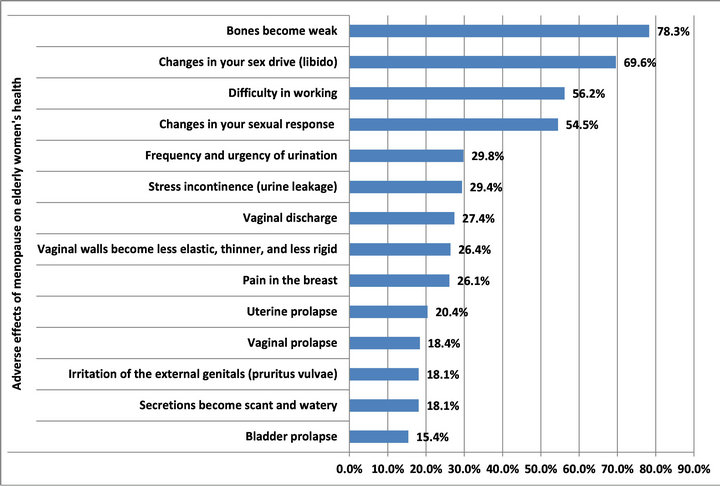

3.2.2. Perceived Health Experiences of Menopause

Figure 6 shows the results of questions about whether women in the study were able to identify and had experienced menopause-related health problems and symptoms. Almost four out of five women (78%) identified weakening bones as a major health change. Other frequently reported changes were in sex drive (69.6%), difficulty working (56.2%), changes in sexual response (54.5%) and urinary frequency and urgency (30%). Bladder, uterine, and vaginal prolapse, decreased vaginal secretion, irritation of external genitalia, were reported as experienced least often.

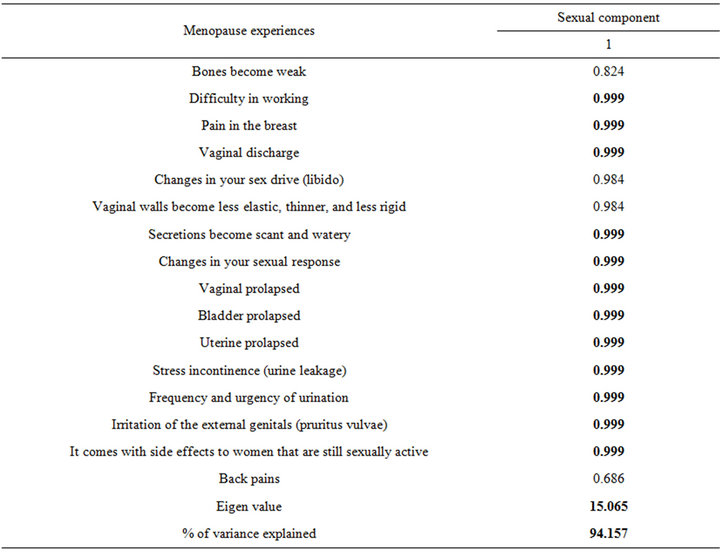

3.2.3. Patterns and Clustering of Health Experiences

Principal component analysis with varimax rotation was used to examine older women’s health experiences. Experiences clustered into one component, the sexual component (Table 5). This component explained a little over 94% of the variation in the linear relationship between the menopause experiences and the sexual component factor.

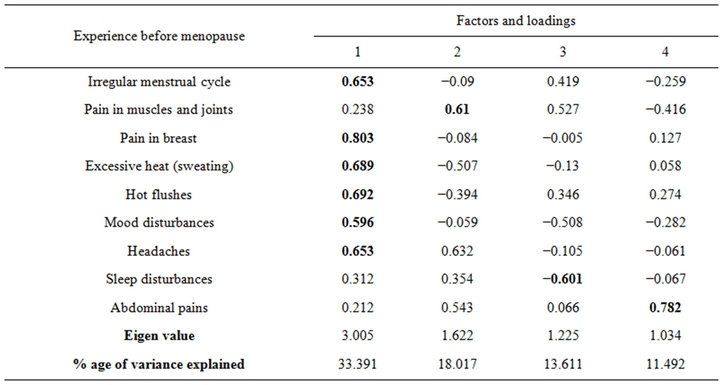

3.2.4. Pre-Menopausal Experiences/Symptoms

The principal component analysis of pre-menopausal experiences revealed four factors (Table 6). The first is described as “sensational factor which is mostly associated, in descending order, with pain in the breast, hot flushes, excessive sweating, headaches and irregular

Figure 5. Opinions about whether menopause can adversely affect health (N = 427).

Figure 6. Perceived health effect of menopause (N = 444).

menstrual periods. This factor/explained one third of the total variation in pre-menopausal experiences/symptoms. The second component, physical pain, is heavily positively associated with the changes: pain in the muscles and joints, and explains 18% of the total variation. The third factor, the sleep component, is heavily negatively associated with sleep disturbances and explains 13.6% of the variation. Finally, the sexual component is heavily positively associated with abdominal pains and explains 11.5% of the total variation.

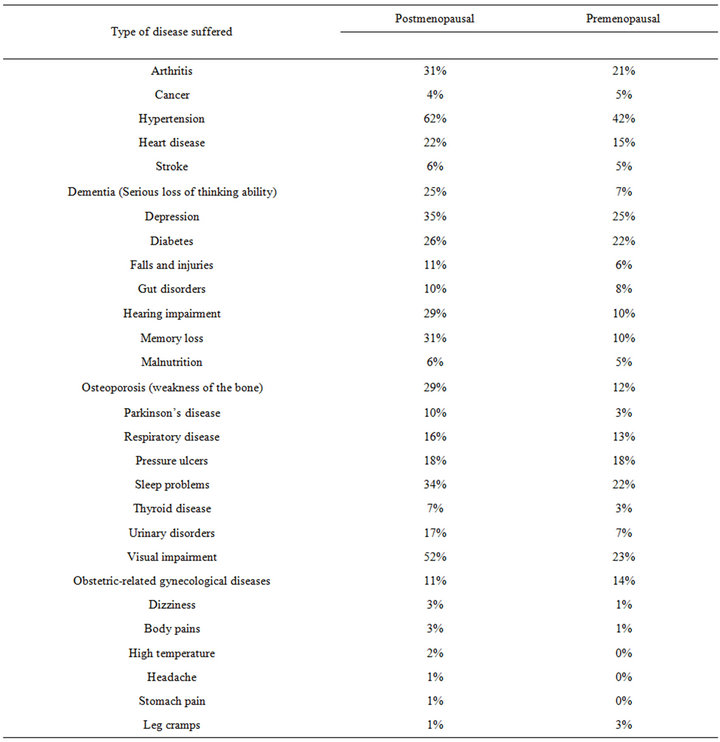

3.2.5. Preand Post-Menopausal Health Problems

There was a strong relation between disease suffered by the older women before and after menopause (correlation coefficient, r = 0.891; n = 444), although the difference in the proportion of the older women suffering from those diseases is not significant (p > 0.01) (Table 7).

Table 7 shows that a higher proportion of occurrence of the diseases is during the post-menopausal period. Hypertension, depression, hearing impairment, memory loss, sleep problems, Osteoporosis (weakness of the bone) and visual impairment occurred most among the postmenopausal older women. This calls for special health intervention for the older women during the post-menopausal period.

3.2.6. Limitations of the Study

The study relied on self-report data from older women, the accuracy of which cannot be verified. Research assistants thoroughly explained the medical terms in the questionnaire, but it is also not possible to evaluate participants’ understanding of these terms. Notwithstanding these limitations, the study design was appropriate for the purpose of the research. The instrument was adequate as can be seen from the high values of the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient and knowledgeable research assistants collected the data under the supervision of the authors.

4. Discussion

Participants in this study of older women and menopause, perceived menopause as: 1) a health situation that comes with medical problems requiring interventions, 2) a positive and normal event which relieves them of menstruation, 3) creating a relaxed mood and 4) a cost saving life change. These results agree with those of [12,28,29]. In [30,31], menopause is seen as beneficial in some cultures as it: frees women of societal taboos and restrictions associated with menstruation and from repeated pregnancies that may be dangerous and stressful due to a lack of medical facilities. In many developing countries, [32] menopause is not seen as natural part of life or as “God’s will” rather than a medical problem. As such, it is accepted with less focus on “symptoms” [18]. But the results contradict a Mauritius study in which over 25% of women, due to lack awareness of menopause, consulted herbalists to treat related symptoms [33]. The most frequently experienced menopause-related change in

Table 4. Attitude toward sex and sexual activity (N = 444).

Table 5. Principal components analysis of menopausal health experiences.

Table 6. Principal component analysis of pre-menopausal experienced symptoms.

respondents’ lives was weakening of bones. Other oftencited changes were in sex drive, difficulty working, and sexual response. These experiences contradict most observed symptoms in other cultures but are consistent with [34], who identified joint and muscle ache, then fatigue, as the most important changes. Hot flushes are the most salient symptom reported in Western cultures [35], but it is non-existent among Maya women in Mexico [34]. Our results thus lend credence to the notion of diversity in symptom frequencies across countries [12,36].

The majority of older women in this study had poor knowledge of menopause and about one in five could not

Table 7. Preand postmenopausal diseases suffered by older women.

remember when they attained menopause. In a similar study by [36], 21% of older women (21%) had no knowledge of menopause and its effects. One’s level of knowledge about a health condition will invariably affect their response to symptoms and to seeking treatment. Educational interventions to increase older women’s knowledge are thus indicated.

While employment and educational status were positively related with knowledge of menopause, other demographic variables were all negatively correlated with knowledge of menopause. Thus being married or experiencing menopause at age 50 or later does not indicate better knowledge. This result is worrisome as it suggests a lack of knowledge about menopause among married women and that women may not worry about the approach of menopause as they perceive it as a normal stage of life. These results agree with [28] in terms of the impact of employment and educational status on knowledge of menopause.

The average age at menopause for study participants was 48.9 years in a country where the average life expectancy of females is 54.51 years. This means that on average, women may experience about 6 years of life after menopause. This result agrees with that of [28,37] where mean age at menopause for 450 menopausal women was 48.22 years and median age was 49 years. These findings suggest that the public health care system in Botswana should focus on the problems associated with menopausal status if the women are expected to meet the requirement of the International Conference on Population and Development in 1994 (Report on the International Conference on Population and Development Cairo, September 1994, United Nations Publication) and be helpful in assisting families care for AID patients and those infected with HIV [38].

There were also no significant differences in the frequency of problems experienced by the older women during their preand post-menopausal periods although in absolute terms post-menopausal women had higher percentages hypertension, depression, hearing impairment, sleep problems and visual impairment than during pre-menopause. Whether this trend is caused by menopause or there are other factors that contributed to increased incidence of these conditions were not investigated in this study. The results are, however, in line with similar studies [39-41] that showed postmenopausal women to experience more vasomotor, sexual and psychological symptoms compared to premenopausal women. The MAHWIS study of Asian women attributed visual changes (becoming short-sighted in middle age) to menopause and high blood pressure [32]. However, [16] showed that the expected problems of pre-menopausal women and those indicated by post-menopausal women in Germany had significantly higher levels of hot flushes, depression, agitation, lack of drive and sexual problems than pre-menopausal counterparts. But there were no difference in terms of cardiac trouble, sleeping problems, vaginal dryness, joint and muscle symptoms. These disparate results affirm that although menopause is a normal process, women are likely to experience it differently depending on individual and sociocultural differences [32, 42].

Finally, the prevalence of sexual activity among the sample could, contrary to expectation, be regarded as slightly high. Close to half of older women indicated a renewed interest in sex after menopause, while 41% wished they could refrain themselves from the urge to have sex, which suggests an ongoing desire. It may thus be inferred that, despite discomfort associated with menopause, [22,33] sexual relationships remain desirable. This finding could be related to cultural aspects of sexuality in Botswana, where women are traditionally not permitted to refuse sexual advances and sex is perceived as a means of socializing [34,40-46]. The results of this study also have important implications for HIV/AIDS prevention among older women, who are biological more vulnerable to transmission of the virus. Again, interventions to increase the knowledge of older women about menopause, including its risks and benefits, should be a public health priority.

5. Recommendation

In the light of the findings from this study, the following recommendations are made:

• The public health care system in Botswana should mobilize resources to improve the awareness and knowledge of older women about menopause and should promote active and healthy living during this stage of life.

• Primary health care personnel should be prepared to educate older women on changes that occur during menopause and available management modalities.

• The public health care system in Botswana should sufficiently recognize and address the health conditions, including menopause, of mid-life and older women.

6. Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the Office of Research and Development, University of Botswana, for the fund provided for this study and to the research assistants for their effort in collecting the data and to Prof Denise Burnette, a full-Bright scholar at the University of Botswana for her very useful comments on the paper and assistance in the language.

REFERENCES

- WHO, “Research on Menopause in the 1990s,” Report of a WHO Scientific Research, WHO, Geneva, 1996.

- N. Osarenren, M. B. Ubangha, I. P. Nwadinigwe and T. Ogunleye, “Attitudes of Women to Menopause: Implications for Counseling,” Edo Journal of Counselling, Vol. 2, No. 2, 2009, pp. 155-164.

- S. D. Harlow, M. Gass, J. E. Hall, R. Lobo, P. Maki, W. Robert. S. S. Rebar, P. M. Sluss and T. J de Villiers, “Executive Summary of the Stages of Reproductive Aging Workshop + 10: Addressing the Unfinished Agenda of Staging Reproductive Aging,” Menopause: The Journal of the North American Menopause Society, Vol. 19, No. 4, 2012, pp. 387-395. doi:10.1097/gme.0b013e31824d8f40

- M. R. Soules, S. Sherman, E. Parrott, et al., “Executive Summary: Stages of Reproductive Aging Workshop (STRAW),” Climacteric, Vol. 4, No. 4, 2001, pp. 267-272.

- Womenshealth.gov. Menopause, 2010. http://womenshealth.gov/men0pause/symptom-relief-treatment

- MNT Medical News Today, “What Is Menopause? What Are the Symptoms of Menopause?” 2009. http://www. medicalnewstoday.com/articles/155651.php

- S. B. Huffman and J. E. Myers, “Counselling Women in Midlife: An Integrative Approach to Menopause,” Journal of Counselling Development, Vol. 77, 1999, pp. 258- 266. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6676.1999.tb02449.x

- S. B. Huffman, J. E. Myers, L. R. Tingle and L. A. Bond, “Menopause Symptoms and Attitudes of African American Women: Closing the Knowledge Gap and Expanding Opportunities for Counselor,” Journal of Counselling & Development, Vol. 83, No. 1, 2005, pp. 48-56. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6678.2005.tb00579.x

- B. Sommer, N. Avis, P. Meyer, M. Ory, T. Madden, M. Kaggwa-Singer, C. Mouton, Adler, S. and N. O. Rasor, “Attitudes toward Menopause and Aging across Ethnic/ Racial Groups,” Psychosomatic Medicine, Vol. 61, No. 6, 1999, pp. 868-875.

- L. Dennerstein, A. Smith and C. Morse, “Psychological Well-Being, Mid-Life and the Menopause,” Maturitas, Vol. 20, No. 1, 1994, pp. 1-11.

- C. Bowles, “Measure of Attitude toward Menopause Using the Semantic Differential Model,” Nursing Research, Vol. 35, No. 2, 1986, pp. 81-85.

- L. Lippert, “Women at Midlife: Implications for Theories of Women’s Adult Development,” Journal of Counselling and Development, Vol. 76, No. 1, 1997, pp. 16-22. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6676.1997.tb02371.x

- S. Greenwood, “Menopause Naturally: Preparing for the Second Half of Life,” Volcano Press, Volcano, 1992.

- B. Strong, C. Devault, B. W. Sayad and W. L. Yarber, “Human Sexuality: Diversity in Contemporary America,” 4th Edition, McGraw-Hill, New York, 2002.

- G. F. Kelly, “Sexuality Today: The Human Perspective,” 7th Edition, McGraw-Hill, New York, 2001.

- I. Kowalcek, D. Rotte, C. Banz and K. Diedrich, “Women’s Attitude and Perceptions towards Menopause in Different Cultures. Cross-Cultural and Intra-Cultural Comparison of Pre-Menopausal and Post-Menopausal Women in Germany and in Papua New Guinea,” Maturitas, Vol. 51, No. 3, 2005, pp. 227-235. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2004.07.011

- M. Hunter, A. Gentry-Maharaj, A. Ryan, M. Burnell, A. Lanceley, L. Fraser, I. Jacobs and U. Menon, “Prevalence, Frequency and Problem Rating of Hot Flushes Persist in Older Postmenopausal Women: Impact of Age, Body Mass Index, Hysterectomy, Hormone Therapy Use, Lifestyle and Mood in a Cross-Sectional Cohort Study of 10418 British Women Aged 54-65,” International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Vol. 119, No. 1, 2011, pp. 40-50.

- B. N. Ayers, M. J. Forshaw and M. S. Hunter, “The Menopause,” Archive, Vol. 24, No. 5, 2011, pp. 348-353

- N. O. Ama and E. Ngome, “The Sexual and Reproductive Health Including Family Planning of Older Women from Selected Sites in Botswana,” A Report Submitted to the Office of Research and Development (ORD), University of Botswana, Botswana, 2012.

- S. Jejeebhoy, M. Koenig and C. Elias, “Community Interaction in Studies of Gynaecological Morbidity: Experiences in Egypt, India and Uganda,” In: S. Jejeebhoy, M. Koenig and C. Elias, Eds., Reproductive Tract Infections and Other Gynaecological Disorders, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2003. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511545627.008

- Central Statistics Office (CSO), “The 2001 Population and Housing Census,” The Government Printers, Gaborone, 2003.

- Creative Research Systems, “The Survey Systems: Sample Size Calculator,” 2003. http://www.surveysystem.com/sscalc.htm

- P. Singh, A. Pandey and A. Aggarwal, “House-to-House Survey vs. Snowball Technique for Capturing Maternal Deaths in India: A Search for a Cost-Effective Method,” Indian Journal of Medical Research, Vol. 125, 2007, pp. 550-556.

- W. P. Vogt, “Dictionary of Statistics and Methodology: A Nontechnical Guide for the Social Sciences,” Sage, London, 1999.

- T. Snijders, “Estimation on the Basis of Snowball Samples: How to Weight?” Bulletin of Sociological Methodology, Vol. 36, 1992, pp. 59-70.

- G. R. Norman and D. L. Streiner, “Biostatistics, the Bare Essentials,” 2nd Edition, BC Decker Inc., London, 2000.

- B. G. Tabachnick and L. S. Fidell, “Using Multivariate Statistics,” 4th Edition, Allyn & Bacon, Boston, 2001.

- I. Loutfy, F. Abdel Aziz, N. I. Dabbous and M. H. A. Hassan, “Women’s Perception and Experience of Menopause: A Community-Based Study in Alexandria, Egypt,” Health Journal, Vol. 12, No. 2. http://www.emro.who.int/publications/emhj/12_s2/article9. htm

- N. F. Woods, B. Saver and T. Taylor, “Attitudes toward Menopause and Hormone Therapy among Women with Access to Healthcare,” Menopause Journal of North American Menopause Society, Vol. 5, No. 3, 1998, pp. 178-188.

- Y. Beyene, “From Menarche to Menopause: Reproductive Lives of Peasant Women in Two Cultures,” State University of New York Press, Albany, 1989.

- M. Flint, “The Menopause: Reward or Punishment?” Psychosomatics, Vol. 16, No. 4, 1975, pp. 161-163.

- M. S. Hunter, P. Gupta, A. Papitsch-Clark and D. W. Sturdee, “Mid-Aged Health in Women from the Indian Subcontinent (MAHWIS): A Further Quantitative and Qualitative Investigation of Experience of Menopause in UK Asian Women, Compared to UK Caucasian Women and Women Living in Delhi,” Climacteric, Vol. 12, No. 1, 2009, pp. 26-37. doi:10.1080/13697130802556304

- R. Hill, “Knowledge Attitudes and Practices on Menopause Symptom Alleviation in Mauritius,” Mauritius Research Council, Mauritius, 2003.

- S. Eman, A. Abdulmajeed and O. Ibtisam, “Assessment of Women Knowledge and Attitude toward Menopause and Hormone Replacement Therapy (HRT) in Abu Dhabi, UAE,” Suez Canal University Medical Journal, Vol. 2, No. 2, 1999, pp. 217-222.

- G. A. Bachmann, “Vasomotor Flushes in Menopausal Women,” American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology, Vol. 180, No. 3, 1999, pp. 212-216. doi:10.1016/S0002-9378(99)70725-8

- N. Nisar, N. Zehra, G. Haider, A. Munir and A. Naeem, “Knowledge, Attitude and Experience of Menopause,” Journal of Ayub Medical College, Abbottabad, Vol. 20, No. 1, 2008, pp. 56-59. http://www.researchgate.net/publication/23488160_Knowledge_attitude_and_experience_of_menopause?citationList=incoming

- L. S. Lynnette, W. Diane and C. Kristophor, “Marital Status and Age at Natural Menopause: Considering Pheromonal Influence,” American Journal of Human Biology, Vol. 13, No. 4, 2001, pp. 479-485. doi:10.1002/ajhb.1079

- N. O. Ama and E. S. Seloilwe, “Estimating the Cost of Care Giving on Caregivers for People Living with HIV and AIDS in Botswana: A Cross-Sectional Study,” Journal of the International AIDS Society, Vol. 13, 2010, p. 14.

- L. F. Jong, J. W. Shun, R. L. Shiang, D. J. Kai and M. C. Lung, “The Kinmen Women-Health Investigation (KIWI): A Menopausal Study of a Population Aged 40-54,” Maturitas, Vol. 39, No. 2, 2001, pp. 117-124. doi:10.1016/S0378-5122(01)00193-1

- C. Harvey, H. T. Bee, C. A. Chia, M. C. Ee, S. C. Yap and M. S. Seang, “The Prevalence of Menopausal Symptoms in a Community in Singapore,” Maturitas, Vol. 41, No. 4, 2002, pp. 275-282. doi:10.1016/S0378-5122(01)00299-7

- A. B. Lori, M. S. Crystal and N. Kavita, “Is This Woman Perimenopausal,” The Journal of the American Medical Association, Vol. 289, No. 7, 2003, pp. 894-902.

- E. Freeman and K. Sherif, “Prevalence of Hot Flushes and Night Sweats around the World,” Climacteric, Vol. 10, No. 3, 2007, pp. 197-214. doi:10.1080/13697130601181486

- G. A. Greendale, N. P. Lee and E. R. Arriola, “The Menopause,” The Lancet, Vol. 353, No. 9152, 1999, pp. 571-580. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(98)05352-5

- P. G. Ntseane, “Cultural Dimensions of Sexuality: Empowerment Challenge for HIV/AIDS Prevention in Botswana,” International Seminar/Workshop on “Learning and Empowerment: Key Issues in Strategies for HIV/ AIDS Prevention, Chiangmai, 1-5 March 2004, pp. 1-21.

- M. Andrikoula and G. Prevelic, “Menopausal Hot Flushes Revisited,” Climacteric, Vol. 12, No. 1, 2009, pp. 3-15. doi:10.1080/13697130802556296

- N. E. Avis, R. Stellato, S. Crawford, J. Bromberger, P. Ganz, V. Cain and M. Kagawa-Singer, “Is There a Menopausal Syndrome? Menopausal Status and Symptoms across Racial/Ethnic Groups,” Social Science & Medicine, Vol. 52, No. 3, 2001, pp. 345-356. doi:10.1016/S0277-9536(00)00147-7