Open Journal of Nursing

Vol.4 No.6(2014), Article ID:45607,6 pages DOI:10.4236/ojn.2014.46044

Online Learning: Advantages and Challenges in Implementing an Effective Practicum Experience

Maureen M. Mitchell, Cheryl Delgado

School of Nursing, Cleveland State University, Cleveland, USA

Email: m.m.mitchell1@csuohio.edu, c.delgado@csuohio.edu

Copyright © 2014 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received 8 March 2014; revised 9 April 2014; accepted 29 April 2014

ABSTRACT

Executing an effective clinical practicum experience for distance learners requires systems to be in place to ensure that all students receive a quality clinical experience and meet course and program objectives. Key to achieving these successful outcomes is recognizing and overcoming the challenges involved in designing graduate practica for Master of Science in nursing candidates. A systematic approach is presented for consideration.

Keywords:Clinical Practica, Distance Learning, Online MSN Programs

1. Introduction

There is a paucity of writing about the special issues of online professional nursing education that has a curricular mandate to provide a clinical experience for students. This may be the greatest faculty challenge: to provide the student with a meaningful clinical experience at a distance.

Much has been written about on the advantages and challenges of online teaching. Advantages that appeal to many students are flexible hours and access to resources not readily available in all geographic areas. Challenges to online learning require that students be self-directed and organized with good time management and writing skills in order to be successful. Educators experience some of the same advantages, and are challenged by continuously evolving technology and increased time commitments for course design and student communications. We would like to share the lessons learned from our experiences in managing the online clinical component of a multi-specialty graduate nursing program.

2. The Online Program and the Unique Challenges for Clinical Practica

The American Association of Colleges of Nursing (AACN) has reported steady growth in enrollments in undergraduate and graduate nursing programs for more than a decade, despite faculty shortages, a lack of sufficient clinical sites and budget cuts in some institutions [1] . Increasingly, graduate nursing programs, both academic and proprietary, are offered online. In 2013 US News and World Report published rankings for 129 on line graduate programs in nursing [2] . In an online program, students may be physically distant, yet participate in a cohort that shares learning goals. A student may be located anywhere the Internet is accessible. While some students live locally, others may reside across the continent or overseas. These distance learning students are “located at a sufficient distance from the home facility, thus preventing instructors from visiting because of time and cost of travel” [3] . This can create a challenge for clinical placements. Some of our students are from the surrounding area, but a significant percentage is from out of state and we have enrolled US citizen students located overseas on military deployment.

Regardless whether the program is brick and mortar or online, accredited graduate nursing programs require a clinical component in the curriculum. Clinical experiences are essential for the student’s integration of skills, theory and critical thinking processes into professional practice [4] . Practicum environments are “crucial links to successful experience(s) for students” [5] . Students want to transfer learning to the workplace and new situations and must “demonstrate their learning in authentic contexts for workplace readiness” [6] . In most states, simulation is not accepted as a substitute for clinical experience, although this has been studied [7] [8] .

3. Facilitating Online Practica at the Graduate Level

Institution-centered clinical experience designed to promote psychomotor skill acquisition is inadequate to address advanced practice learning needs. At the Masters level there is a shift in focus from the acquisition of psychomotor skills and critical thinking to the development of analytical thinking and the refinement of organizational and prioritization ability [9] . These learning outcomes are better accomplished through a mentored practicum experience in which the relationship between teacher and learner is more collegial and the setting is broader allowing the student to model professional and practical hands on learning. A practicum experience provides anticipatory guidance for more independent practice [10] .

The ability to engage in this style of learning allows the course instructor to monitor and guide the clinical experience of multiple students across a variety of practice settings and physical locales. Anticipatory guidance is important for online learning as well as in face to face courses and may be enhanced by the more frequent communication with the online instructor. The online student has a course instructor and a clinical mentor which provides even more learning support. “A unique aspect of quality online courses is how they rely heavily on effective collaboration to create a meaningful learning environment” [6] . Our graduate program offers five learning tracks for advanced practice: nursing education, specialty populations (health alteration based), Clinical Nurse Leader, forensic nursing, and a combined MSN/MBA. Our school philosophy features a population-based curriculum. Students at the graduate level are expected to identify a population of interest upon which to center their course work and practica. “Practicum experiences are selected and planned to provide students with opportunities to work across settings and manage care for varied professions…” [5] .

4. Executing a Clinical Practicum Agreement

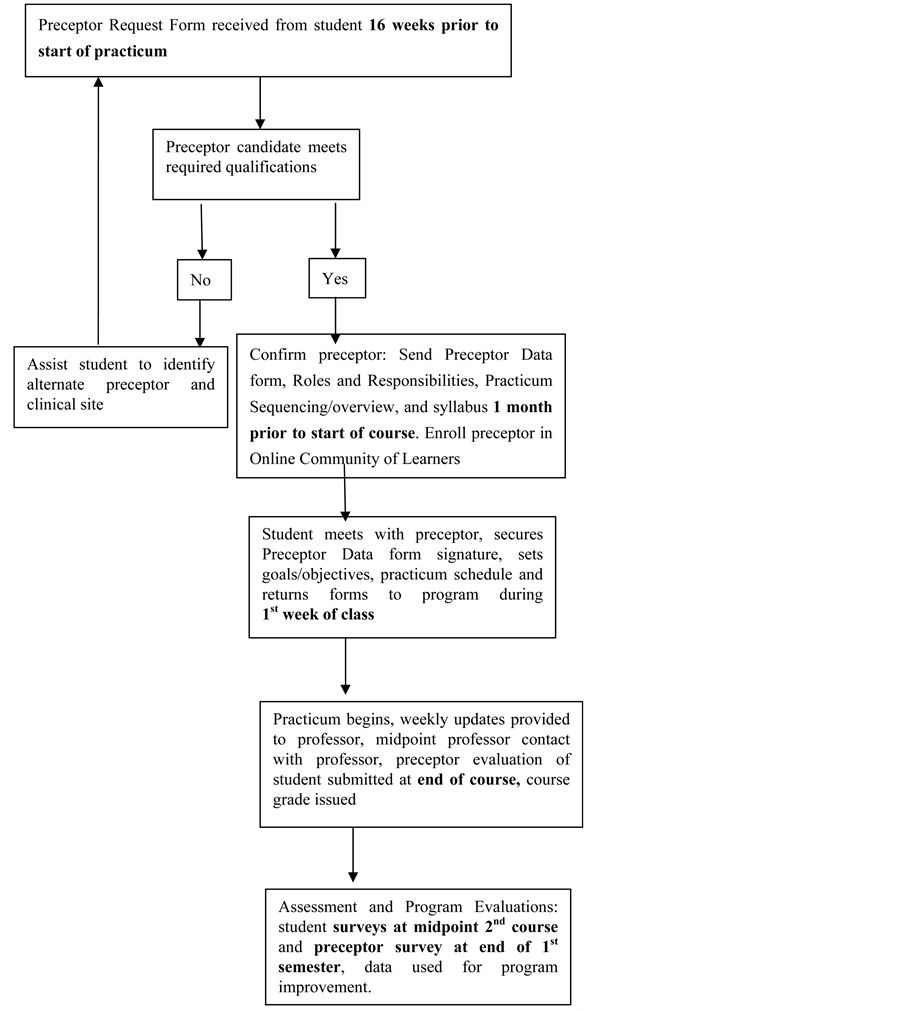

Students, faculty and specialty area preceptors work together to create an optimal clinical experience. This begins with matching the student with a qualified preceptor. At minimum, preceptors must possess a Master of Science in Nursing (MSN) and have clinical experience with the population of interest to the student. Sixteen weeks prior to the first clinical course, students are required to submit a preceptor request which indicates their academic track, clinical focus, and the names of potential preceptors. Our program has three sequential clinical practica courses starting in the fall of each academic year so the Preceptor Request Form is due April 1. Often students may be in a position to determine if the preceptor is a good fit for their specialty and may be more aware of the local reputation of the preceptor candidate and the practicum site. However, if the student is unable to identify a preceptor or clinical practicum site, the professor assists the student in locating potential preceptors for consideration. The early date for preceptor preferences allows time to fully process the request and subsequent practicum agreements (see Figure 1). Student and preceptors are expected to commit to work together for all three clinical courses.

Figure 1. Preceptor/student placement procedure and timeline.

The number of qualified preceptors willing to serve in this role is becoming more limited. Growing competition from increasing numbers of on line programs and the preceptors own professional responsibilities, including the need to master multiple new technologies have shrunk the pool of willing preceptors [11] .

The willing preceptor candidate is contacted by a faculty team member and receives information on the preceptor role and responsibilities, practicum sequence expectations, and copies of forms used for student evaluation. They are asked to complete a Preceptor Data Form documenting their qualifications as required for accreditation and licensing agencies. A Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) is executed to establish the relationship and liability parameters for preceptor and faculty. Be aware that negotiating an MOU may involve the legal departments of both the university and clinical practicum site. Therefore, allow enough time for the agreement to be edited, reviewed and signed by the appropriate authorities. Once the relationship is formalized, the student and preceptor meet to arrange the practicum schedule and identify expected performance outcomes established for the course.

Since the program is offered in a distance learning format, the signed Preceptor Data form is one of the most important mechanisms that we use to validate the legitimacy of the practicum agreement. If students fail to secure the signed Preceptor Data Form prior to the start of the clinical practicum, no clinical hours are counted. We have found this strategy to be effective in cementing the relationship between the student and preceptor whereby all parties are in agreement on the roles and responsibilities for the practicum experience. One may appreciate that the student has a vested interest in securing this form in order to be able to proceed with the clinical practicum.

5. Unique Challenges for Online Programs

There are challenges in the clinical facet of distance programs. These center on finding qualified preceptors who can provide structure and guided direction for the experience in order to ensure and maintain consistency in the learning experience. The lack of preceptors is noted to be one reason nearly 30 percent of nursing programs cite for turning away qualified applicants to their programs [12] . Sobralske and Naegele believe “finding clinical sites and qualified NP preceptors is the biggest challenge for FNP programs and is a time consuming and costly endeavor” [13] .

With five specialty tracks including special populations, nursing education, and forensic nursing, a match with an experienced preceptor is critical. Preceptors can be especially difficult to find in emerging fields where credentialed nursing practitioners have not reached sufficient numbers to form a readily accessible pool. In these specialties, non-nurse preceptors may be an option. Forensic nursing students have worked with medical examiners, rape crisis counselors, criminal prosecutors, lawyers, and law enforcement. No matter the specialty, preceptors should have the ability to communicate effectively, teach their skills and facilitate student access to the population of interest and the interdisciplinary services and programs used by the population.

6. Ensuring Program Consistency

Several strategies are used to maintain consistency in the learning experience for all students. Each of the clinical courses has set course and learning objectives and it is the responsibility of the course instructor to reinforce and guide student and preceptor toward achievement of those objectives. Learning goals are clearly articulated, achievable and measurable. Although course objectives, based on Commission on Collegiate Nursing Education (CCNE) Essentials for Masters Education in Nursing [14] are set and non-negotiable, the faculty acknowledges that there are varying routes to learning achievement. Students, in consultation with their preceptors, identify measureable project outcomes or “deliverables” for which the students are evaluated at the end of each course. Correlating course work and clinical content so that they occur simultaneously is not always possible, as clinical events are unpredictable. Electronic resources such as videos and organizational websites can engage student interest but the greatest factor in developing student engagement has been individualized responses to questions and concerns. Carr [15] refers to this as tele-mentoring or the ability of the faculty to “reach out, communicate and support students from a distance”.

So as to maintain a level playing field for all students regardless of specialty, evaluation criteria are consistent and one evaluation form is used. Once again, the Preceptor Evaluation of the Student evaluation form is required to be completed and signed by the preceptor and student and returned to the School of Nursing before a course grade is issued. As with the Preceptor Data Form, these documents are filed in the students’ academic file for auditing and accreditation purposes.

7. Establishing an Online Community of Learners

The most important strategy in maintaining an optimal learning environment is good communication and support from the program administration. As our program is online, we have established an online faculty community using the Blackboard Learn™ learning platform to share information and documents, and to create a collegial environment that includes those who cannot attend faculty meetings. The university provides Guest Access Accounts for preceptors who are not employees of the university, thus ensuring that all preceptors have access to resources required to facilitate the practicum experience (e.g., evaluation forms, roles and responsibilities, explanation of the practicum sequence).

Preceptor training is important to the success of the placement as well as ongoing communication among all stakeholders. Souder, O’Sullivan Staab and Dobbins [16] found vigilant monitoring of student and preceptor involvement important and identified two significant red flags: lack of interaction in online activities and absence of clinical discussion online. Our university supports student achievement and retention through subprograms in the online delivery platform that monitors student participation and grades, alerting the faculty to students who consistently submit assignments late, miss assignments or consistently earn poor marks. When questions concerning student performance are present, the observations and cooperation of the preceptor are essential to diagnose and remedy the situation. In a like manner, if the preceptor does not feel that that student is working well at the practice site, they are encouraged to contact the faculty for consultation.

8. Program Assessment and Evaluation

Our program assessment plan includes surveying students and preceptors for satisfaction and input to improve the process of preceptor assignment and practicum experience outcomes. Our experience has taught us that preceptor placements are sometimes difficult, but essential to a quality program and require a good match based on student input and well qualified preceptors that enjoy the support of the program administration and course instructor. Setting up a clear and transparent system, along with continued contact and the communication of learning objectives and resources will support the student and preceptor in the clinical experience and promote a successful practicum experience.

9. Conclusion

Overall, clinical components to graduate courses serve an important function by allowing students to put newly acquired skills into practice. Online programs are not excused from the requirement to provide clinical experiences, but face some challenges in providing them to distance learners. Identifying and securing qualified preceptors may require innovative recruitment. All preceptor placements require cooperation and collaboration from program and university administrations, as well as from the course instructor, preceptors and students. Faculty members serve as an essential link and resource for preceptors and students and good communication among all three promotes a successful learning experience and student satisfaction. It also increases the likelihood that preceptors would be willing to assume this essential role again at a future time with another student. Although difficult, preceptor guided clinical placements for distance students in online programs are worth the planning and effort for everyone.

References

- Stiffler, D., Arthur, A., Stephenson, E., Ray, C. and Cullen, D.L. (2009) A Guide for Preceptors of Advance Practice Nursing Students Caring for Women and Infants. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, and Neonatal Nursing, 38, 624- 631.

- US News and World Reports (2013) Best Online Nursing Programs. http://www.usnews.com/education/online-education/nursing/rankings

- Yonge, O. (1997) Assessing and Preparing Students for dis Tance Preceptorship Placements. Journal of Advance Nursing, 26, 812-816. http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2648.1997.00316.x

- de Tornyay, R. and Thompson, M.A. (1987) Strategies for Teaching Nursing. 3rd Edition. John Wiley and Sons, New York.

- Stokes, L.G. and Kost, G.C. (2009) Chapter 17: Teaching in the Clinical Setting. In: Billings, D.M. and Halstead, J.A., Eds., Teaching in Nursing (3rd Edition), Saunders Elsevier, Philadelphia.

- Fisher, M. (2003) Designing Courses and Teaching on the Web. Scarecrow Education, Lanham.

- Pauly-O’Niel, S., Prion, S. and Nguyen, H. (2013) Comparison of Quality an Safety Education for Nurses (QSEN)- Related Student Experiences during Pediatric Clinical and Simulation Rotations. Journal of Nursing Education, 52, 534-538.

- Schiairet, M.C. and Pollock, J.W. (2010) Equivalence Testing of Traditional and Simulated Clinical Experiences: Undergraduate nursIng Students Knowledge Acquisition. Journal of Nursing Education, 49, 43-47. http://dx.doi.org/10.3928/01484834-20090918-08

- Reimer, M., Thomlinson, B. and Bradshaw, C. (1999) Practicum Guide for Nurses. Delmar Publishers, Albany.

- O’Connor, A. (2001) Clinical Instruction and Evaluation: A Teaching Resource. NLN Press, Jones and Bartlett Publishers, Boston.

- Hawkins, S. (2012) Telehealth Nurse Practitioner Student Clinical Experiences: An Essential Educational Component for Today’s Health Care Setting. Nurse Education Today, 32, 842-845. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2012.03.008

- American Association of Colleges of Nursing. (2012) New AACN Data Show an Enrollment Surge in Baccalaureate and Graduate Programs Amid Calls for More Highly Educated Nurses. http://www,aacn.nche.edu/news/articles/2012/enrollment-data .

- Sobralske, M. and Naegele, L.M. (2001) Worth Their Weight in Gold: The Role of Clinical Coordinator in a Family Nurse Practitioner Program. Journal of the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners, 13, 537-544. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-7599.2001.tb00322.x

- American Association of Colleges of Nursing (2012) The Essentials of Baccalaureate Education for Professional Nursing Practice. Washington DC.

- Carr, K.C. (2003) Innovations in Midwifery Education. Journal of Midwifery and Women’s Health, 48, 393-397. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jmwh.2003.08.006

- Souder, E., O’Sullivan, P.S., Staab, A.M. and Dobbins, W.N. (2005) Identifying Red Flags in Distance Learning Clinical Experiences. Paper Presented at Sigma Theta Tau 38th Biennial Convention in Indianapolis, Indiana, 12-16 November 2005.