Open Journal of Nursing

Vol.3 No.3(2013), Article ID:34949,6 pages DOI:10.4236/ojn.2013.33041

Public health nurse observations of behavioral characteristics of fathers who contribute to the emotional instability of mothers, as presented in cases of infant abuse

![]()

Department of Nursing, Sapporo Medical University, Sapporo, Japan

Email: iueda@sapmed.ac.jp

Copyright © 2013 Izumi Ueda. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Received 20 April 2013; revised 21 May 2013; accepted 15 June 2013

Keywords: Child abuse; Father; Experienced Public Health Nurse; Characteristic; Behavior

ABSTRACT

The objective of this study is to look at the understanding and perceptions of public health nurses (PHNs) related to behavioral characteristics of fathers that contribute to emotional instability in mothers by reviewing abuse cases involving infants and very young children. A qualitative descriptive design was applied to the data analysis, based on a semi-structured interview administered to three experienced PHNs who had been in charge of maternal and child health services for at least five years at a public health department or health center; with the data obtained in the interview narratives analyzed. In the observations of the experienced PHNs, the behavioral characteristics of fathers who are instigators of child abuse can be classified into five categories, fathers who are: “Talking to others about marital problems without attempting to solve these by themselves”, “Working on learning about childcare seeking to correct childcare methods”, “Taking the initiative in childcare at cross purposes with mothers”, “Stressing the effort they (the fathers) put into childcare”, and “Failing to notice the own family situation and problems”. The findings of the study suggest the necessity for PHNs to understand fathers, to be aware of the difficulty of building a supportive relationship with fathers, and to improve skills enabling the PHNs to help fathers form good relationships with other family members.

1. INTRODUCTION

The 7th Report on “Verification of causes of deaths from child abuse” [1] outlines details of deaths from all child abuse cases. The incidence of deaths of children of less than one year of age due to child abuse is the highest (40.8%), and the total for children up to five years of age is about 90%. Therefore, early infancy is a specifically important time to be able to provide supportive intervention in child abuse cases.

Many studies conducted outside Japan have focused on fathers to establish risk factors contributing to child abuse, including studies of fathers displaying high risks of being the source of physical abuse or neglect, general risk assessment, and the roles of fathers in abuse and neglect cases [2,3]. In Japan, there are reports comparing the characteristics of biological mothers and fathers, as well as there is a report of intervention with groups of fathers in Tokyo [4,5], and this field has recently attracted research attention. However, there are few studies that focus on the characteristics of fathers. The reason why the research progress in Japan differs from other countries may be due to the differences in societal perceptions, including differences in the length of time researchers have focused on child abuse as a social issue and in behaviors pertaining to child abuse.

Based on the Maternal and Child Health Law of Japan, PHNs at public health departments and health centers have provided maternal and child health services for infants and women in childbirth [6]. The present study conducted interviews with experienced PHNs who had been involved in child abuse cases while providing maternal and child health services, and investigated the opinions (understanding) of the behavioral characteristics of fathers who contributed to the emotional instability of mothers by reviewing infant abuse cases.

2. METHODS

2.1. Operational Definitions of Terminology

1) Child Abuse

There are different definitions of child abuse. The Child Abuse Prevention Law of Japan defines both physical abuse such as striking and kicking and sexual abuse, as well as psychological abuse and neglect under the umbrella term “child abuse”.

In this study “child abuse” is defined as physical abuse, psychological abuse, and neglect as stipulated in The Child Abuse Prevention Law. Some studies have reported that the pathology of sexual abuse originates in perpetrator factors, such as the desire for emotional contact, sexual stimulation [7]. Sexual abuse was excluded from the study here because the pathology of sexual abuse may be seen to differ from the other types of child abuse.

2) Father

“Father” here refers to either a biological father or to a person viewed as a father to the children, a male who plays the role of father to a child.

2.2. Design and Sample

In A Prefecture the study identified a region where social resources such as medical welfare services for children are well established, and made the request for cooperation at health care centers where permission to approach the personnel had been obtained. At a health care center, we recruited participants (interviewees) from among experienced PHNs, personnel in charge of maternal and child health services at the onset of the study and with at least five years of experience in dealing with child abuse cases. The types of abuse that the participating PHNs would be interviewed about were limited to physical abuse, mental abuse, neglect, or a combination of these, but no specific identification of the family member instigating the abuse in the family was indicated.

Data were collected from semi-structured interviews based on interview guidelines and were conducted from September to November of 2009. Upon obtaining consent, the narratives were recorded using IC recorder, and the interviews lasted an average of about one hour. The interviewees were requested to recall a father they had assisted in their capacity as PHN and tell about the case. All the interviewees talked about the cases referencing the case records which were available at the interview. Firstly, the participants were asked to outline the causes of the case, including details of the family structure. The main questions in the interviews were: 1) characteristics of the father and events and occurrences in the case, and 2) events where the interviewees perceived difficulties and for events that stood out or were memorable. The interview was conducted in the work place of the interviewee in a location where privacy could be ensured.

2.3. Data Analysis

The data obtained by recording and transcribing the narratives were analyzed by employing a qualitative descriptive design, and classified by the relevance of a sentence or of content that appeared to suggest a matter of importance. Examining the contexts which showed characteristics of the fathers and assigning a coded marker which would not hide the meaning, a coded list of these items was created for each interview. With all the cases to be analyzed, organizing the codes of similar contents, and reviewing the concepts represented by the content, the data were classified into subcategories. Then, identifying similarities in the subcategories and examining the items assigned, each subcategory was assigned a name to be abstracted. In this process the abstraction level was carefully monitored with final assignation to a category, from subcategory, code, and data. The validity of the categories was assured by repeated coding and discussion among the co-researchers. For verification of the results, the interviewees were asked to check for variance with the facts or for other problems in the extracted categories and subcategories and whether the categories reflected the contents they had brought up.

2.4. Ethical Considerations

This study was carried out after obtaining informed consent to participate by explaining the outline of the study to the director of the participating health care center orally and through the letter to request participation in the study. The outline of the study was also explained to the participating PHNs orally and through the letter to request participation in the study, and written consent was obtained. Participants were assured that confidentiality would be maintained at all times, research findings would not be used for purposes other than the study, and the cases would be carefully handled as would also the anonymity of both PHNs and others involved in the cases. We obtained the approval of the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Health Sciences, Graduate School of Health Sciences, Hokkaido University (No. 08-56).

3. RESULTS

3.1. Research Participants and Outline of the Cases

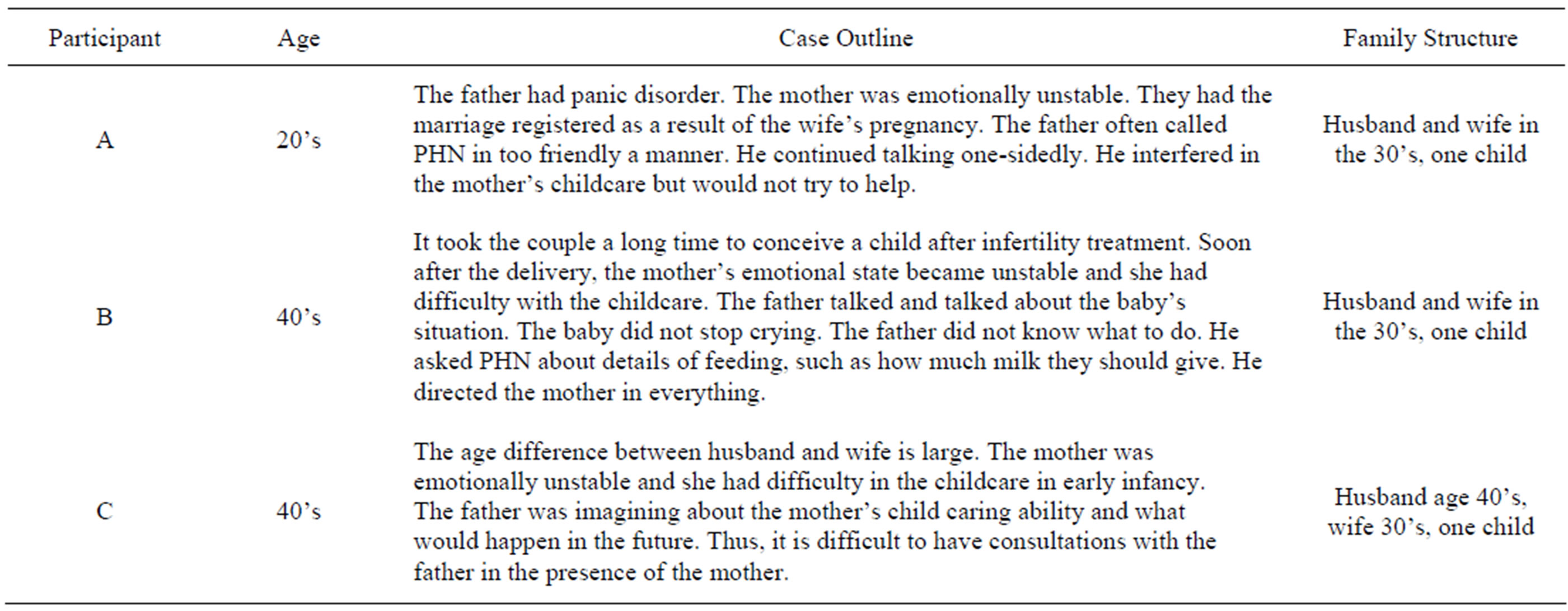

The total number of cases brought up by the interviewees was three. All were cases where the mothers were mentally unstable, and were experiencing difficulty in the care of the children involved. There were cases of neglect by the parents but no cases of physical or psychological abuse (Table 1). All the cases were with nuclear families. The cases all involved infants in situations where the determination of abuse was made by the PHNs

Table 1. Details of interviewees, cases, and participants.

and supportive intervention was provided by the PHNs.

3.2. The Result of Analysis of Father’s Behavioral Characteristics

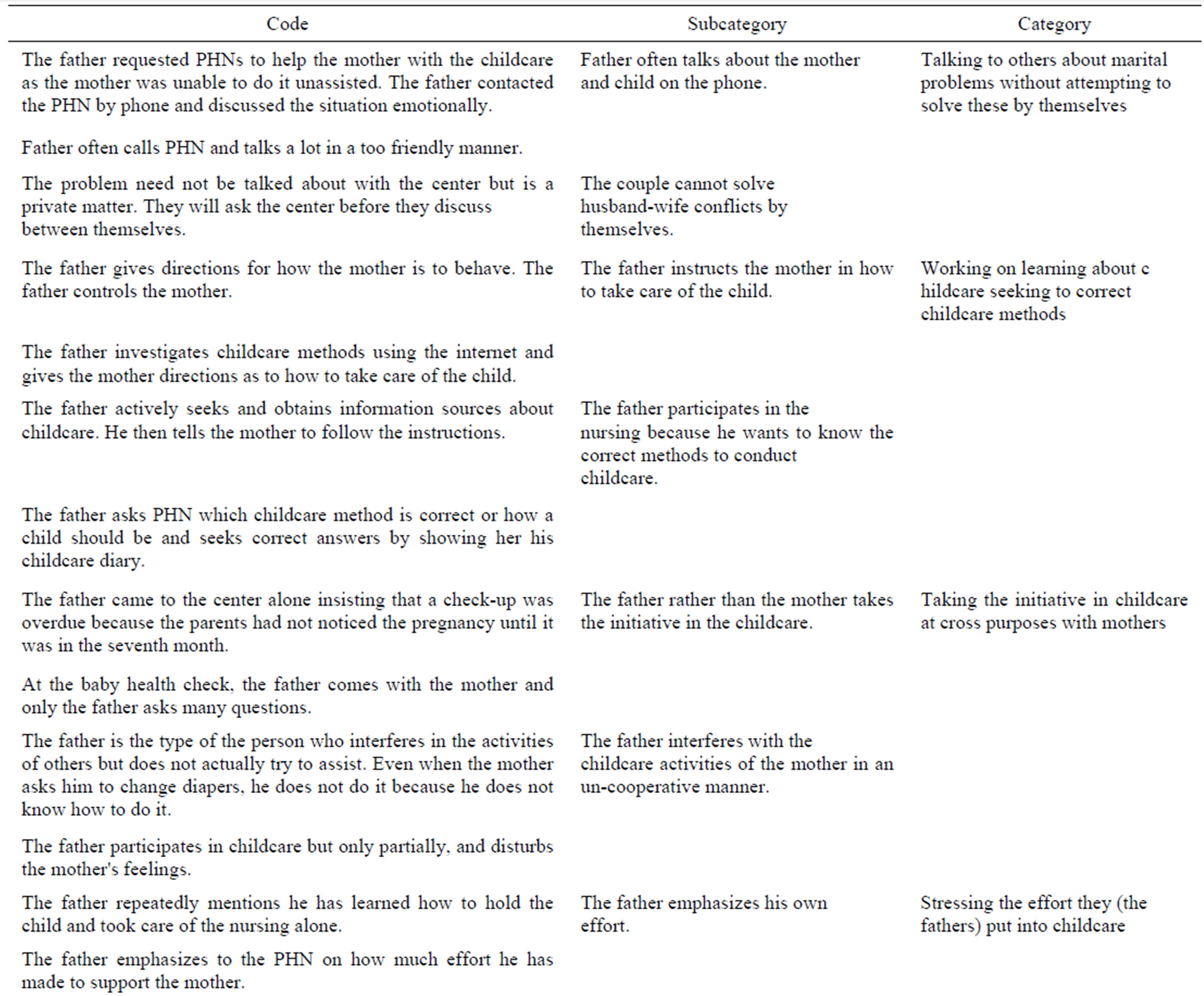

The analysis yielded 5 categories and 11 subcategories (Table 2). The categories, subcategories, and codes are expressed with single quotation marks (‘ ’), double quotation marks (“ ”) marks, and square brackets ([ ]), respectively.

1) ‘Talking to others about marital problems without attempting to solve these by themselves’

This category is comprised of two subcategories: “Father often talks about the mother and child on the phone.” and “The couple cannot solve husband-wife conflicts by themselves.” The interviewees reported that [The father requested PHNs to help the mother with the childcare as the mother was unable to do it unassisted. The father contacted the PHN by phone and discussed the situation emotionally.] and [I think the husband and wife should solve the problems by themselves. The problem need not be talked about with the center but is a private matter. They will ask the center before they discuss between themselves.]

2) ‘Working on learning about childcare seeking to correct childcare methods’

This category is comprised of two subcategories: “The father instructs the mother in how to take care of the child.” and “The father participates in the nursing because he wants to know the correct methods to conduct childcare.” The interviewees reported that [The father gives directions for how the mother is to behave. The father controls the mother.] and [The father actively seeks and obtains information sources about childcare. He then tells the mother to follow the instructions.]

3) ‘Taking the initiative in childcare at cross purposes with mothers’

This category is comprised of two subcategories: “The father rather than the mother takes the initiative in the childcare” and “The father interferes with the childcare activities of the mother in an un-cooperative manner.” The interviewees reported that [The father came to the center alone insisting that a check-up was overdue because the parents had not noticed the pregnancy until it was in the seventh month.] and [The father is the type of the person who interferes in the activities of others but does not actually try to assist. Even when the mother asks him to change diapers, he does not do it because he does not know how to do it.]

4) ‘Stressing the effort they (the fathers) put into childcare’

This category has one subcategory, “The father emphasizes his own effort.” The interviewees reported that [The father repeatedly mentions how he gets up during the night to take care of the child, has learned how to hold the child and took care of the nursing alone.]

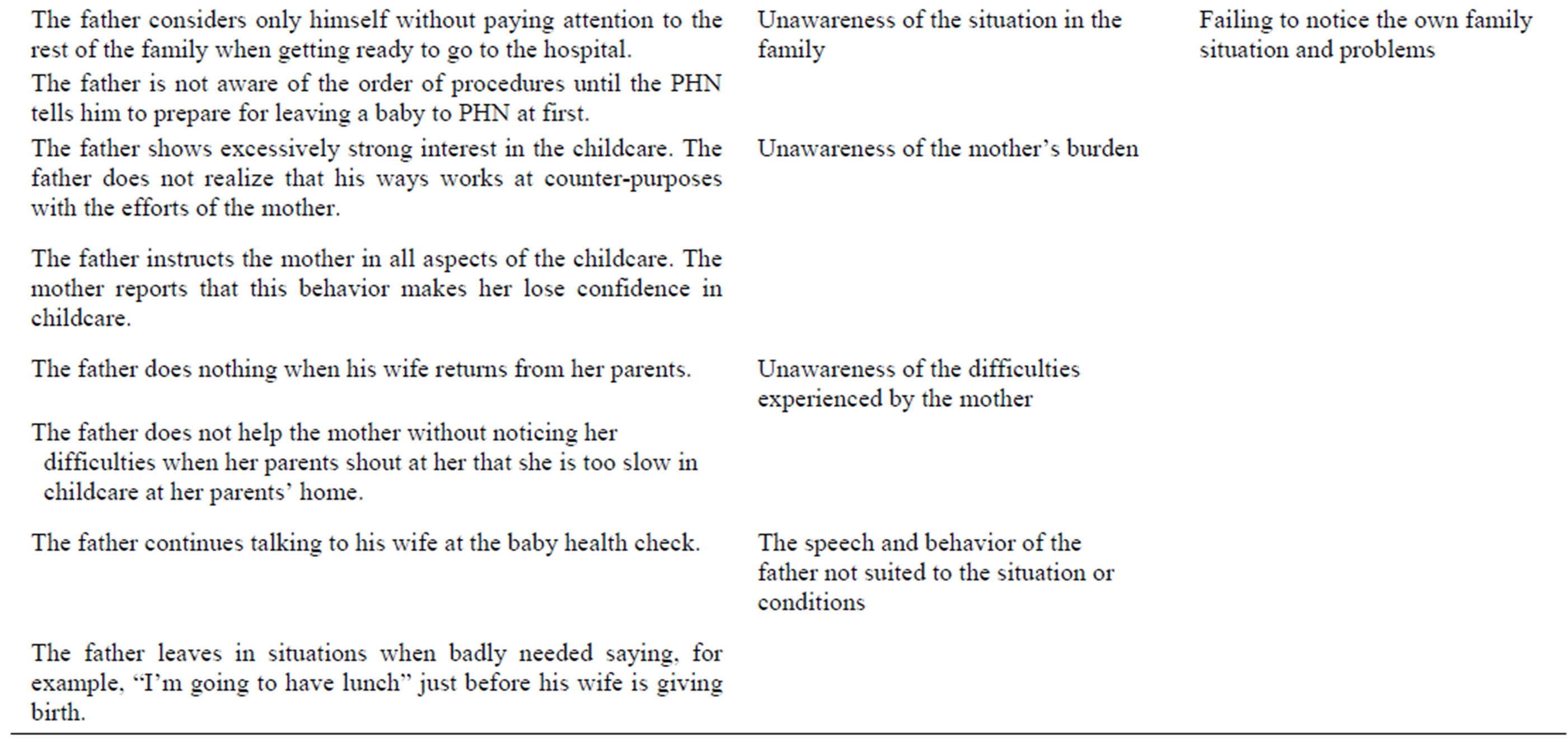

5) ‘Failing to notice the own family situation and problems’

This category is comprised of four subcategories: “unawareness of the situation in the family,” “unawareness of the mother’s burden,” “unawareness of the difficulties experienced by the mother,” and “the speech and behavior of the father not suited to the situation or conditions.” The interviewees reported that [The father considers only himself without paying attention to the rest of the family when getting ready to go to the hospital.] and [The father shows excessively strong interest in the childcare. The father does not realize that his ways works at counter-purposes with the efforts of the mother.]

4. DISCUSSION

The categories ‘Talking to others about marital problems without attempting to solve these by themselves’ and

Table 2. Observations of PHNs of behavioral characteristics of fathers that contribute to emotional instability of mothers in child abuse cases.

‘Working on learning about childcare seeking to correct childcare methods’ here represent behaviors that the fathers do because they cannot solve the problems by themselves.

Findings from a previous study related to family’s risk factors for child abuse show that the factor of fathers not taking responsibility to their own behavior leads to situations where abuse occurs [8]. Therefore, it is important for fathers to realize their own responsibility in the role they play in the family. Data in the present study implies that fathers do not perform their roles with sufficient responsibility when dealing with childcare problems. Further, instabilities in the marital relationship has been brought up as a characteristic of families that are more likely to commit child abuse [9]. Considering the father characteristics identified in this study, then if a father acts depending on others without making own decisions, this contributes to mental unease of the mother and makes the marital relationship unstable.

It is often difficult for PHNs to understand the intentions of fathers because they do not readily make decisions. The PHNs have trouble understanding the behaviors of fathers, but it is still important to understand the mental background to the actions of fathers, such as the sense of values and emotions hidden by the behavior appearing to depend on others.

The categories ‘Taking the initiative in childcare at cross purposes with mothers’ and ‘Stressing the effort they (the fathers) put into childcare’ here represent attitudes that show how the fathers try to be actively involved in childcare. According to a nationwide survey by the Japan Society of Family Sociology, a non-cooperative attitude of a husband in childcare is associated with the likelihood of the mother committing child abuse [10]. Therefore, the cooperation of the father in childcare is important for child abuse prevention. The findings from the present study show that fathers make efforts in childcare but that this may result in complicating the mental health of mothers. The PHNs need to provide specific instructions about childcare for fathers to reduce the childcare burden on mothers to ensure mental stability and thus assist fathers in their efforts to participate in the childcare.

The category ‘Failing to notice the own family situation and problems’ here suggests that there is a pace of activity that is unique to fathers. A study on the sympathy toward family members of parents with a high risk of child physical abuse and gender difference reports that high risk mothers have more personal troubles than low risk mothers and fathers, while high risk fathers are less likely to accept conditions in an objective manner and have lower sympathy thresholds than low risk mothers and fathers [11]. The findings in that study point to fathers with high risks of causing child abuse to have low sympathy thresholds toward other family members and that they are less likely to accept conditions and occurrences in an objective manner. In other words, they are less likely to perceive and recognize how others feel. It is, however, not clear whether psychosocial features, such as a father’s low level of sympathy toward other family members and the tendency not to accept things objectively, are common in Japan. It may be inferred that the behavioral characteristics of fathers identified in this study: not actively deciding matters and not noticing problems in the family, arise as the fathers are less likely to perceive and recognize how others feel. However, it is necessary to understand the mental background to the actions of fathers, such as the sense of values and emotions hidden behind the superficial behavior.

In the case of fathers who can neither solve marital problems arising from husband-wife relations nor notice family problems, there is a high risk of conflicts arising among family members, which leads to intensification of the risk factors contributing to child abuse. For fathers who acts at cross purposes with the mother in matters of childcare and do not notice the burden this imposes, mothers will become subject to stress build up. Many previous studies have focused on mothers and there are only a few that address the characteristics of fathers. However, it is still necessary to provide support by considering the marital relationship while focusing on mothers who commit abuse.

5. LIMITATIONS

The present study has the following limitations: we addressed only cases that were dealt with by PHNs who worked in public health centers. The types of abuse were limited to neglect due to mental instability of the mothers. The characteristics of the fathers were not characteristics reported by the fathers themselves or others involved, but the characteristics perceived by the PHNs.

6. CONCULUSION

The findings of the study could be employed as basic data for assessing risk factors of fathers pertaining to infant abuse cases, and suggest ideas for what may be considered characteristics of fathers and supportive interventions. For the characteristics of the father, it was possible to identify five categories: ‘Talking to others about marital problems without attempting to solve these by themselves’, ‘Failing to notice the own family situation and problems’, ‘Working on learning about childcare seeking to correct childcare methods’, ‘Taking the initiative in childcare at cross purposes with mothers’, and ‘Stressing the effort they (the fathers) put into childcare’, with eleven subcategories. The findings also suggest that it is important for PHNs to provide support based on an understanding of the mental aspects of fathers that are hidden in the background of the abusive behavior, and through this to improve skills and understanding to be able to help fathers better.

7. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The research team expresses thanks to the participants for accepting to be interviewed and making room in their busy schedules. This study was conducted as a part of the research supported by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (2009-2012), Basic Research (c) (21592843), (research representative: Izumi Ueda).

REFERENCES

- Committee on Council of Social Security of Children SeCtion Concering Child Abuse (2009) The 7’s Analysis Reports by Death Cases of Child Abuse and Neglect. http://www.mhlw.go.jp/bunya/kodomo/dv37/dl/7-2.pdf

- Cindy, M., Pamela, C., Kimberly B., et al. (2005) Predicators of child abuse potential among military parents: comparing mothers and fathers. Journal of Family Violence, 20, 123-129. doi:10.1080/028418501127346846

- Coohey, C. (2006) Physically abusive fathers and risk assessment. Child Abuse & Neglect, 30, 467-480. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.10.016

- Department of Health and Welfare, Metropolis of Tokyo (2007) The 2nd Report on the Actual Situation of Child Abuse. http://www.mhlw.go.jp/bunya/kodomo/dv36/index.html

- Takeshi, T. (2007) Psychoeducational approaches for families: Concept and methods: Approaches for fathers group. Kanekosyobou Press, Tokyo.

- Chilldren Abuse (2009) The Care Manual of Faters/Mothers/Children-by Tokyo. Koubundo Press, Tokyo.

- Izumi, U. and Kazuko, S. (2009) 6-1 public health nurse’s care for mather and child health, new child care for neighborhood action. Chuuouhoukisyuppan Press, Tokyo.

- Yuri, M. (2008) Sexual Abuse to Children, Iwanamisyoten Press, Tokyo.

- Moore, D.R. and Florsheim, P. (2008) Interpartner conflict and child abuse risk among African American and Latino adolescent parenting couples. Child Abuse & Neglect, 32, 463-475. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2007.05.006

- Ayaka, M., Yukie, K., Keiko, S., et al. (2005) Parents’ feeling regarding infants and child-rearing and the influence on mild child abuse tendencies. Japanese Journal of Child Abuse & Neglect, 7, 222-229.

- Perez-Albeniz, A. and de Paul, J. (2004) Gender differences in empathy in parents at highand low-risk of child physical abuse. Child Abuse & Neglect, 28, 289- 300. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2003.11.017