Open Journal of Ecology

Vol.05 No.05(2015), Article ID:56236,14 pages

10.4236/oje.2015.55014

Cattle Counting Ceremony among the Wolaita (Ethiopia): Exploring Socio-Economic and Environmental Roles

Yacob Hidoto

Dilla University, Dilla, Ethiopia

Email: jacobcheka@yahoo.com

Copyright © 2015 by author and Scientific Research Publishing Inc.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Received 25 March 2015; accepted 7 May 2015; published 12 May 2015

ABSTRACT

Livestock play significant roles in the lives of different peoples in Ethiopia. The importance of livestock and culture associated with them has got a greater impetus in the post-conflict political reform in Ethiopia. The 1990s reform provided opportunities for various ethnic groups to resuscitate aspects of their traditions that were suppressed under the previous regimes. The purpose of this study is to explore socio-economic and environmental roles of cultural based notion of cattle counting rite of the Wolaita People. The practices of cattle counting of Wolaita are called as Dala and Lika, which refers to ceremonies of public displaying of one’s own cattle wealth numbering minimum of, respectively, hundred and thousand cattle. The Dala and Lika ceremonies honor men. However, there is also Gimuwa ceremony which honors women. The ceremony of cattle counting is accompanied by the lavish feasts and series of rituals. The central figures in cattle counting rite are wealthy farmers who wish to achieve social prestige by demonstrating their cattle wealth. The practices have got a greater attention by the farmers of Wolaita since the fall of the socialist regime in 1991. Using ethnographic technique, this article tried to explore the practices of the Dala, Lika and Gimuwa, focusing on how the cattle counting rite gives economic and social status to the farmers and ensure environmental sustainability.

Keywords:

Cattle Counting Rituals and Feasts, Social Prestige and Status, Livelihood and Wealth

1. Introduction

Livestock has a great place in the African lives. The Horn of Africa is a well-known region in terms of its livestock number. For example, studies indicate that some 70% - 80% of rural peoples in the region rely on livestock for livelihoods [1] . Livestock play significant roles in the lives of different peoples in Ethiopia in terms of livelihood, employment creation, social security and ensure environmental sustainability [1] .

There are many culturally significant practices associated with cattle/livestock in the Horn of Africa. Such practices are transcendent ethnic boundaries, and play the greatest roles in the everyday life of their owners as well as their communities [2] [3] . Culturally embedded value of cattle has much to clarify the socio-economic and environmental roles of possessing cattle. This article wishes to explore cattle counting rite and its socio-eco- nomic and environmental relevance among Wolaita People of Southern Ethiopia.

Cattle have always been part of Wolaita agriculture. Cattle remained as important means of livelihood and social relations in the rural areas of the region. Most of the traditions and culture that were associated with cattle are still relevant, albeit the cattle wealth of Wolaita was significantly depleted after its incorporation into the Ethiopian empire state in the late 19th century [4] . Cattle associated culture is one of the defining marks of the Wolaita identity. Unlike the classic cattle pastoralists of east Africa, who have relatively larger household herds, there are few livestock per household in Wolaita and they live in the same house as their owner, and are given a greater care. The cattle counting ceremonies of Wolaita, namely Dala, Lika and Gimuwa have great meanings to both rich farmers who wish to conduct the rite and those farmers who are in joint ownership with them.

The cattle-counting ceremonies are being practiced with a greater impetus by rich farmers in Wolaita, particularly in Kindo Didaye Wereda (district). Notwithstanding this empirical situation, academicians who have carried out a valuable study in aspects of Wolaita ethnography [4] -[6] did not pay enough attention to aspects of cultural practices associated with cattle counting. Thus this paper aims to explore cattle counting ceremonies and feasts and their social, economic, and environmental importance. Data were collected through ethnographic te- chniques such as in-depth interview and focus group discussion with farmers, elders and public officials in various part of the Wereda in 2014. The following text intends to shed light on this issue. A second section provides brief overview on theoretical issues. A third section will explore the study setting. A fourth section will explore Dala, Lika and Gimuwa rituals. This section pays more focus on exploring and analyzing the economic, social and environmental roles of cattle counting rite of Wolaita. Finally, the conclusion will be provided.

2. Theoretical and Conceptual Frameworks

Cattle/livestock rearing and cultural practices associated with cattle can be viewed from different theoretical frameworks that are relevant to conceptualize the role of cattle counting rite of Wolaita. Thus, this section will shed light on different perspectives that are relevant to capture economic, social and environmental values of cattle counting ceremonies of Wolaita.

2.1. Contributions of Cattle to Livelihood and Wealth

A large numbers of people rely on cattle in Africa for their livelihood. Cattle herding is important to create income, food security and nutrition, social security and poverty reduction. Animals are kept for their meat, hides and milk Cattle provide an important option to farmers to diversify their economic activities. Livestock also provide a major economic activity and serve as a major source of sustainable employment for many rural areas. The trade in livestock products forms an important economic driver, especially in urbanizing societies with rising incomes [1] [3] [7] .

Most people in the rural areas of Ethiopia get their income from sell of livestock and their product. Livestock products play significant roles in the food they eat. Milk cows are particularly values and milk products are being increasingly commercialized. This has been true for a long time since livestock has been sustainably used despite widespread occurrences of drought and diseases. Most of the household incomes are generated from sell of household livestock and remained as a single most important source of income for most Ethiopians. Cattle serves as an asset that can be converted into cash needed to purchase of clothes for children, inputs like fertilizers and improved seeds for the next crop production cycle. Absence of regular rain and limited farmland in the most rural areas of Ethiopia mean livestock is a sustainable means of rural development albeit most of cattle herders are poor farmers [7] [8] .

Cattle ownership in terms of its quantity and quality is an important issue to farmers and it is one of indicators of food security. As studies show, households that are food self-sufficient are known to have high livestock, indicating that increased cash incomes primarily came from livestock, through the sale of live animals, milk, meat, hides and skins [1] . Cattle ownership also indicates wealth. For example, in most part of Africa household wealth and the values of other goods are measured in cattle [9] [10] . Unlike land which is generally not seen as an aspect of household wealth due to the fact that it has been owned by groups with households holding only usufruct rights, cattle did and to some extent still do function quite literary as money. Rich farmers for example produce grains mainly to buy livestock. Even if there are some risks in livestock accumulation like losing them to drought and disease, cattle continue play important roles to food security and wealth accumulation to the rural farmers.

2.2. Social and Ritual Values of Cattle

Some scholars highlight about the mythical and ritual values of cattle. The notion of “cattle complex” that was initially coined by the Melville Herskovites [11] , for example, expresses traditional attitudes held by the Africans towards cattle. The notion of “cattle complex” that visualized the Africans cattle ownership in religious and social terms was developed due to the fact that Africans were not raising cattle for a market and commercial basis. However, concept of “cattle complex” that focus on social values of cattle has been criticized for its exclusive emphasis on socio-religious values of cattle. Mtetwa [12] argues that the fact that women and cattle were interchangeable value in Africa shows that the main motive behind the urge to acquire cattle was economic, albeit it was obscured by the prevalent social values. Mtetwa also argues that the Africans reluctance to sell their cattle in the market was related to low market price. Farmers do not want to sell their cattle because they know their cattle values will increase the longer they stay at home [12] . In this aspect, cattle ownership is regarded very much as shares and investments are in the capitalist society.

Cattle ownership gives prestige and social status. According to Nicole Poissonnier [13] a man can get prestige and social status by organizing a big feasts at which he slaughter a large number cattle for the attendants to eat. Eating and drinking are provided by a rich farmer who wants to demonstrate his great herd of cattle and their fertility. Feasts of this kind play various roles in the lives of peoples. They create and maintain social relations that bind people together in various ways [14] . For example, they are extremely important in establishing sentiments of friendships, kinship and community solidarity as well as cementing bonds between affine groups. However, scholars who wrote about means of getting social prestige in the Ethiopian contexts tend to underestimate social prestige that come through cattle ownership compared with social prestige associated with hunting of wild animals or killing a man belonging to another ethnic group that is considered to be an enemy [3] . This assertion in turn misses crucial transformation that takes place among quite a large number of ethnic groups in Ethiopia. Many ethnic groups have successfully adopted non violent means of getting social prestige and status. There is also tendency to generalize that Africans lives are centered more around “consumption” than around “transformation” that is the ability to get people to do things [14] .

2.3. Environmentalist Views towards Cattle/Livestock

From the perspective of concern to environment, cattle herding affects the environment. For example, animals use large amount of basic resources like land and water. Over grazing and greenhouse gas emissions are also associated with traditional pastoralism [15] . Cattle herders usually focus on social and economic values of their cattle disregarding the environmental impact of cattle herding. Evidently, prioritizing of economic and social interest at the expense of environment has a greater risk for ecological sustainability. However, as experiences of small-scale Wolaita cattle rearing and cattle counting ceremonies indicate, livestock and cultural practices associated with cattle are not devoid of sensitivity towards the environment. As it will be elaborated in the forthcoming sections, farmers of Wolaita are not only sensitive towards economic and social values of their cattle but also they are also concerned with depletion of resources.

3. The Study Setting

3.1. The Society

Wolaita is one of 56 ethnic groups that reside in Southern Nation, Nationalities and Peoples Regional State of Ethiopia. Socio-culturally and linguistically, Wolaita is closely related to Ometo peoples such as Gamo, Gofa, Kucha, Dawuro, Konta and Basketo that share similar language with no or little dialect. Wolaita is inhabited by over 1.8 million people [16] .

Politically, Wolaita had a strong centralized Kingdom before its incorporation into the Ethiopian empire state in the late 19th century. Two clans had ruled the kingdom till the late 19th century. Similar kingdoms also existed among other Ometo areas. But the clan alliance was dominant form of identification in all areas of Ometo.

The society is composed of more than 130 clans that share similar customs [17] [18] . Most of these clans also exist in other Ometo areas, particularly in Kucha, Boroda, Dawuro and Konta. In these societies similar clans do not marry each other. However, clan alliance has little to do with economic relationship in general and cattle share ownership in particular. Historically, membership of clan determined to a large extent entitlement to inherit land, local political alliances and ritual celebrations [4] . Traditionally, Wolaita society is also composed of the royal clan known as kawonata at the top of the society, the free farmers at the middle and slaves together with occupational minorities at the bottom. The social interaction between the farmers and the occupational minorities was limited. For example, they did not marry each other, albeit though such relationship is now changing.

As shown in Figure 1, Kindo Didaye Wereda which is one of twelve Weredas in Wolaita Zone is the first historic settlement areas of the people of Wolaita. Most of earliest remembered history of the people are said to have occurred here in southwest part of the zone. The major economic activity in the Wereda is agriculture, that is, mixing crop-livestock production. The land is suitable for crop-livestock production as most of the people inhabited in the mid-altitude zone. However, shortage of farmlands remains one of main problems for the inhabitants. As a result, each household has few numbers of livestock. Yet livestock holding per household is highly valued.

In terms of religion, the major religion in Kindo Didaye Wereda is Protestantism and followed by Orthodox-

Figure 1. Map of Wolaita Zone (source: http://touristinfo.ning.com/photo/damot-mountain-27).

Christianity and traditional beliefs. Followers of all religious beliefs conduct cattle counting rite, albeit rituals associated with cattle counting namely Dalla and Lika are actively pursued by the followers of traditional belief and to some extent by the Orthodox Christians. Among traditional beliefs ancestral worship, sorcery, witchcraft, the evil eye and Gome were common and some of these are still believed [19] .

3.2. The Resurgence of Cattle Counting Ceremonies in Wolaita

The Dala, Lika and Gimuwa rituals have been widely practiced among Ometo-Wolaita people since long time. The practice is surviving among the neighboring Cushitic peoples, particularly the Hadiya ethnic members who inhabit around the Gibe valley. The Dala, Lika and Gimuwa ceremonies along with marriage, funeral ceremonies and hunting of wild animals are some of the cultural practices that have largely practiced by the Wolaita people. However, cultural practices associated with cattle are mainly surviving in the remotest areas of Wolaita. Their presence in other Ometo inhabited areas is very limited [20] .

Livestock have always been part of Wolaita agriculture. Pastoralists were pre-dated agriculturists in Wolaita’s history. Before its incorporation into the Ethiopian empire state in the late 19th century, Wolaita appears to have been a golden age for the native people with many cattle per household. Wolaita was fertile, wealthy with an abundance of forests, large unsettled areas and large numbers of cattle and wildlife [5] . Nonetheless, the kingdom was conquered and looted by Amhara-dominated force led by Menelik in 1894. At the end of the campaign, for example, Menelik divided a rich booty, keeping 18 thousand head of cattle and 18 hundred slaves for himself. The invasion and subsequent feudal-based administration actively set out to ruin the country for suppressing any popular resistance against the state [4] . The huge number of livestock and people taken away from the area undermined the agricultural base, resulting in lasting stress, albeit the cattle remained as important means of livelihood in rural areas. Shortage of land in Wolaita and lack of access to bank in rural areas mean investment in cattle is primary target of many of farmers. As such, most of the traditions and culture associated with cattle are remained unaffected in the inaccessible rural part of Wolaita, albeit the cultural practices were discouraged through the state policies that consider them as backwardness.

Nonetheless, the importance of livestock and culture associated with them has got a greater impetus in the post-conflict political reform in Ethiopia. The 1990s federal reform that has decentralized power from centre to regions and sub-regional units provided a considerable degree of self-rule to various ethnic groups in the country. Each ethnic group has got opportunity to resuscitate aspects of their traditions which were suppressed under the previous regimes [19] . The reform has informally reinforced the resurgence of the Dala, Lika and Gimuwa rituals and increased investment in livestock. Since buying and selling of land was considered as illegal in Ethiopia after the 1975 land reform, the rich farmers have turned to livestock as an investment. As such, in the Kindo Didaye Wereda the numbers of individuals who are conducting cattle counting rituals are increasing since 1990s.

4. The Dala, Lika and Gimuwa: The Rituals and Their Socio-Economic and Environmental Roles

Public displaying of cattle wealth in Wolaita is categorized into two stages. The first one is Dala rite in which a rich cattle owing farmer counts at least one hundred cattle. The second stage is Lika ritual which requires possessing at least one thousand cattle. The Dala and Lika ceremonies honor men. However, there is also Gimuwa ceremony which honors women. Dalla and Gimuwa rituals and to some extent Lika have been widely practiced in the study area.

4.1. The Dala Ritual

The Dala is a ritual whereby a rich farmer publically displays his cattle wealth. The word “Dala” literary means pieces of metals that make a loud sound and are tied at the neck of a cow and an ox at the end of cattle counting rite to mark public recognition of cattle wealth of a person. In order to perform Dala ritual, the person should possess cattle between one hundred and one thousand. In reality, the size of cattle can be even more than one thousand, but it should be at least one hundred. As the informants remember, in the earlier times, the item subjected to the counting were not confined to cattle; it also included both material goods such household utensils including utensils reserved for rituals, farm tools, luxurious clothes as well as live animals such as goats, sheep, horse, mules, donkeys and hens. However, currently cattle wealth displays are largely confined to cattle albeit essential goods such as inherited clothes and gifts are usually displayed at place arranged for the guests. In Dala ceremony, the size of other animals is notified to the attendants as part of life story of the person. Majority of Dala conducted in the Kindo Didaye Wereda were more than three hundred cattle albeit many of the cattle were share owned with the poor farmers who were unable to afford to buy them alone.

Being able to perform Dala ritual requires hard working to accumulate cattle wealth. It is difficult to perform the ritual without saving and investment on animals. Reproduction of cows saved since the time of young age has a great contribution to accumulate cattle wealth. It is believed that early owned cows are not for sell, but to be reproduced. Income from off-farm activities is often important to accumulate cattle wealth as richer farmers also earn income from off-farm activities. Trading is important source of off-farm income. As early as 1900s, there were advanced market transactions in Wolaita. There are now big weekly and small daily markets all over Wolaita. Some of rich farmers who were able to carry out Dala ritual have generated income by engaging in relatively large-scale profitable trade such as buying and selling of animals, timber, coffee, clothes, land, grains and so on.

Many of the cattle owned by rich farmers are in share ownership with the poor farmers. The rich may own half of a cow or one fourth or own it fully. If a cow is fully owned by the rich person, the usual contractual agreement between him and the poor is to share the profit from sell price or share “womb” of the cow. The poor share holder has duty to provide milk and milk products, particularly butter at least once with each new birth. He/she has also a duty to bring the cows/oxen to be counted in the day of Dala/Lika ritual. Shareholding requires ties that bases on blood relation, friendship, neighbors, religious affiliation, commitment and trust.

The decision to conduct Dala often comes after series of informal conversation and encouragement by family members, friends and the elders. That conversation may take a year or more depending on the size of cattle wealth of a person who wishes to conduct the Dala or Lika ritual. The relatives or neighbor often put pressure on up the potential candidate or Dalaawa (as referred in the study areas) to take practical steps to perform the ritual. To the relatives and neighbors, his/her status is a matter of getting or maintaining prestige of the village or district or specific clan that the person belongs. Discourses in wealth, popularity and wisdoms are also very important to the day-to-day interaction among members of different villages or clans. In other words, for many persons who want someone to be glorified in the village, it is a matter of not to be seen inferior in wealth and fame, which have significant implication on most daily interactions of farmers in rural areas. Sometimes such pressure comes with covert arrangement to contribute the cattle that do not belong to the potential Dalaawa in order to increase the size of cattle during the day of the ritual, albeit such act is socially unacceptable.

Once a rich farmer decides to hold Dala ritual, one big event is marking day (Keeroo Gallasa) that heralds news of the beginning of the preparation for the actual cattle-counting ritual day. Relatives, friends, neighbors, shareholders, elders, guests and other individuals who have already carried out the rituals are invited to hear the plan and contribute their own experience to the event. The day also marks identifying all relevant wealth that belongs to the candidate; this is important to get confidence of the attendants who are ready to tell his fame. Furthermore, during that day all immediate relatives and neighbors pledge what she/he want to contribute to the ceremony, mainly in terms of food and drink, or animals to be slaughtered during the ritual day or promises to cover costs of indigenous musicians or other costs. The potential Dalaawa has upper in deciding what he want from each person. On the other hands, each member of the relatives and neighbors has cultural obligation to commit themselves to fulfill what they fledged to provide. After all, each person wants to identify with the potential Dalaawa who would be publically recognized for his handwork and failing to contribute something to his ceremony is socially shameful act. The potential Dalaawa on his part shows generosity to the attendants by preparing to them an extensive feast. The feast of Keeroo Gallasa day end by fixing actual date for the Dala ritual, which often occurs after two or three months after the marking day. The best time to perform the ritual is from December to April when the harvest and rain are over, and the farmers have money to expend on social events.

On the actual day, all shareholders bring the cattle to the Dala ceremony at the early morning. According to the tradition each shareholder has a duty to honor his/her partners even if the candidate has the smallest share in a cow. If the residence of the shareholder is furthest away from the residence of the potential Dalaawa, or if the cow is pregnant or sick, the shareholder has responsibility to bring a rope that representing the number of cattle he/she shares with the Dalaawa. Cattle that were bought to be slaughtered for the feast do not take part in the counting process.

The counting takes place in especial designed place. The location where the Dala ritual takes place is usually around main road in the village and should be suitable to accommodate such a large numbers of cattle and participants. If the person did not possess such land, he buys it from someone who is willing to sell stripe of land for the ritual purpose. The selected location fended with the trunk of local trees that not only serves as wall of the enclosure but also they are expected to grow as a permanent tree, and remain sacred place forever transferring crucial message of the ritual from generation to generation. The fences are built in a circular way that also include a major pole at the middle which in turn serves to lay bundle fruits (buluwa) that represent the number of cattle counted in the enclosure. The enclosure generally looks like the indigenous house of Wolaita albeit the former lacks the roof.

As tradition dictates, the person who counts the cattle should be the one who has already hold the Dala ritual. And the person is named as “Molana” and he wears especial clothe named Kole. He is also trusted friend of the potential Dalaawa and should be an esteemed elder in his village. As shown in Figure 2, he counts the cattle using leaf of a tree that is edible by animals. He immerses that leaf in a pot that contains blood mixed with milk, butter and honey and beats the cattle so that they may enter into the enclosure designed for the counting. The blood in the pot comes from an ox and sheep that are slaughtered for that ritual purpose. Its intension is to safeguard the cattle against disease and to wish a long life for the Dalaawa. If the fence is unable to accommodate more cattle, he counts the remaining cattle in the vicinity of the fence. He also counts the ropes of cattle repre- senting missing cattle. The first cow that is allowed to enter the enclosure should belong to the species of the first heifer that the candidate has ever owned. Molana ties Dalas (pieces of metal) in neck of a cow and ox that belongs to that species. These cattle herald the ceremony to everyone who hears the sound of the pieces of metal at their neck; these cattle remain in the house of Dalaawa. At the end of the counting, Molana receives a mature ox that he chooses from the cattle he counted.

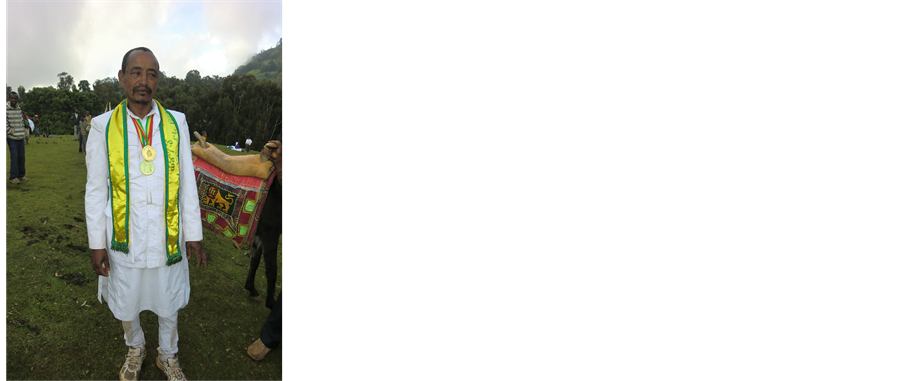

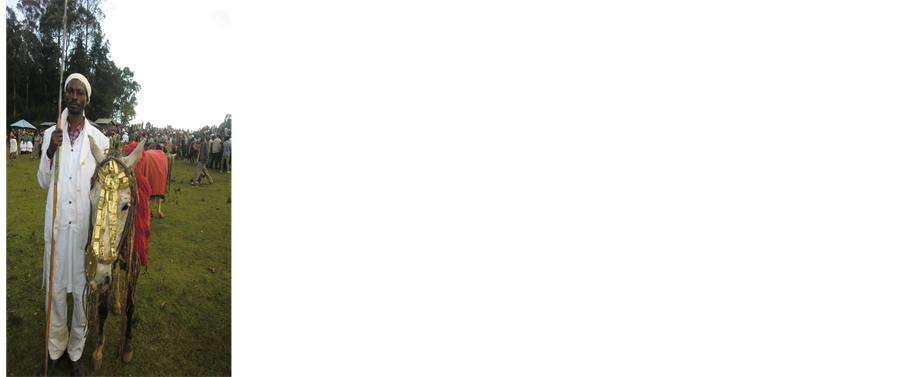

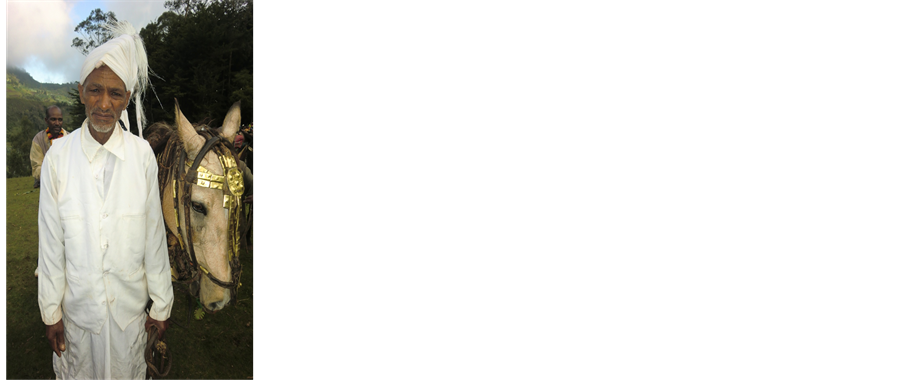

In the whole ceremony Dalaawa and his family members particularly his mother or wife are major actors. As shown in Figure 3, Dalaawa wears especially made white clothes starting from head to feet seat on the horse and stage the show by telling his deeds, that of his forefathers and friends who supported him. Dalaawa uses idiomatic expression that highlights respect he has, his wisdoms, his wealth and great deeds of men in his village, raising a case to the observers to find their own hero to honor. He is accompanied by his relatives and friends who also appreciate his deeds in local idioms such as Gayruwa and Geressa. They honor the Dalaawa, singing honorary songs “wostatakee sallaqe, wogotettaa darotette”. These are traditional songs. But the Christians prefer to use songs that rather praise God: “Tossaw hashu, Yesusawu hashu”. Family members such as wife and sons position themselves at both right and left side of the Dalaawa. While the counting takes place, the horsemen and horsewomen rotate around the enclosure honoring the Dalaawa. At end of the counting the Dalaawa gives the Dala (pieces of metal) to the Molana to mark the public recognition of cattle wealth accumulated by the person. The Dala ceremony honors mainly Dalaawa. Wife or mother of Dalaawa is honored in a ceremony

Figure 2.Cattle being counted in the enclosure during Dala ceremony of Zeleke, Gocho (adopted from the video originally taken by Paulos C. 2013, available at the Kindo Didaye Wereda Culture and Tourism Bureau).

Figure 3. Dalaawas (from left to right): Satane Ginja (Gale); Ono Mena (Sere) and Bezabe Basa, Bereda (photos taken by the researcher 2014).

known Gimuwa, which will be explored later.

One of the main events in the Dala ritual is commensality that is eating and drinking together. Eating and drinking take place at especially designed place at the residence of Dalaawa. One of main food items served in the feast is meat and its products. During Dala ritual, the Dalaawa is expected to slaughter ten cattle which are identified to be fat among others. As shown in Figure 4, some of indigenous foods presented to the guests are meat, kochikochuwa, sulssuwa, guguwa, wotaya, pila, loggomuwa, muchuwa and so on. Major drinks served in the feast are esa and farso albeit soft and alcoholic beverages that are produced in industries were now widely used in the feast. The generous feast provided to the attendant give a crucial moment to reflect on social issues, talk about great deeds and fames of Dalaawa and to take some lessons. The place of commensality are often arranged in a way that the attendants observe material wealth of the Dalaawa and his family, his gardens (darkua) and farm (shoqa) and house in general. Furthermore, the music and dance, and songs accompany the feast to motivate the guests particularly youths so that they may diligently work to accumulate wealth and aspire for public recognition of it.

4.2. The Lika Ritual

The word Lika refers to excellence in terms of cattle wealth, money and wisdom. As a ritual, Lika means displaying one’s cattle wealth in a publically to the invited guests. To achieve the status of Likaawa (as referred in the study area), a person must have at least one thousand cattle including those he shares with other individuals. Since the Lika ritual requires accumulating more than one thousand cattle, few individuals succeed in conducting the Lika ritual. A person who wishes to conduct Lika ritual has to achieve first Dalaawa status; even if a person possess more than one thousand cattle, it is not acceptable to start from Lika without conducting Dala ritual earlier, albeit counting more than thousands cattle during Dala ritual is acceptable and bring more fame and prestige to a person. Dalaawa has to add more cattle to the ones that he already owned during the Dala ceremony. Some Likaawa also include animals such as goats, sheep, horse, mule and donkey in the Lika ritual, but the addition of other livestock relies on personal decision of the potential Likaawa.

The Lika ritual is similar in many aspects with that of the Dala. The preparation, the selection of site for establishment of the enclosure, feasts, clothing, music, dance, use of idiomatic expression to glorify of the person and the timing of the ritual are similar with that of the Dala ritual. However, the far greater prestige and wealth associated with the Lika ceremony means the number of guests and attendants are much greater than that of the Dala ritual; so is the extent of feast prepared to the guest and attendants. According to the tradition, potential Likaawa has to prepare one hundred cattle to be slaughtered for the feast, albeit in reality few cattle are slaughtered for the guests. Likaawa has to serve not only invited guests who also contribute some money (yesa), but also many persons who came either to observe or take part in the feast. The tradition also requires that the person who conducts Lika ceremony has to show unrestricted generosity to the participants, particularly to the poor.

Figure 4.Feast during Zeleke’s Dala ritual (adopted from the video originally taken by Paulos C. 2013, available at the Kindo Didaye Wereda Culture and Tourism Bureau).

Once a person decides to carry out the Lika ritual, he invites his relatives, neighbors, friends and famous elders to set the date for the ceremony and fix type of gift (Chacha) he expect from his relatives and friends. Actual preparation takes places starting from that date onwards. The site for cattle counting is usually located near former Dala site; food and drinks are prepared and the messages are disseminated to the shareholders and guests about the ceremony.

According to the informants, the Lika ritual has remarkable difference in terms of the number of cattle wealth and intricate rituals associated with it. Obviously, the person should have at least one thousand cattle. Other livestock can also be counted. The person who wishes to conduct Lika also displays his material wealthy such as his clothes, beauty of his house, the garden, and other things he wants to show the participants. The Lika ritual is accompanied by a unique ritual that usually intended to test the genuinely of his cattle wealth. The ritual is named Huluko, which does not exist in Dala ceremony. As shown in Figure 5, the Huluko ritual requires two holes dug underground with tunnels connecting them. The depth of the holes is usually equal to height of the candidate; they are expected to be filled with blood mixed with milk, butter and honey. The candidate has to enter into one hole and should cross the tunnel filled with blood and come out through the other hole.

At the day of the Lika ritual every shareholders bring the cattle to the place arranged for the counting rite. The candidate and his attendants, wearing the required traditional clothes, come to the ritual site. They sing songs using idiomatic expressions that glorify the candidate. After they reach the site, Molana start counting the animals. He directs the animals to enter the enclosure arranged for the counting using a leaf of tree intended to spray blood with mixed butter, milk and honey upon the cattle. The counting also includes the ropes to represent animals that are not brought to the ritual place.

A crucial event that heralds the end of Lika ceremony is Huluko ritual. This ritual comes after the end of counting the cattle. The candidate goes to the holes filled with milk, butter and honey. On the site the candidate slaughter a cow and sheep using his spear and add their blood into the holes that have already been filled with milk, butter and honey. Then, he takes off his white clothes and enters into one side of the hole with his underwear. He has to cross the tunnel into the other side swimming on the blood mixed with butter, milk and honey.

According to the tradition the elder son is not allowed to assist the Likaawa when he is performing the Lika ritual. This is intended to avoid the likelihood that he may push down and suffocate his father in the blood in order to immediately inherit the cattle. Rather, the tradition allows someone who is very friendly to the Likaawa or his eldest daughter to support him particularly when he is coming out of the blood.

Successful accomplishment of the ritual heralds not only the public status of the candidate as Likaawa but also embolden him not to care about any risks in the rest of his life. After coming out the blood, Likaawa put on his clothes; holding his spear, he starts to speak out his great deeds using expression that liken him to other great heroes remembered in the area and beyond. Larger numbers of attendants recognize his greatness and wealth and admire him with idiomatic expression like Gererisa and Gayriwa.

Another great event that marks the Lika ceremony is commensality. Invited guests and observers take part in drinking and eating after the end of the ceremony. The feast associated with Lika takes extended days; and are accompanied by music and dance that entertain the participants. The foods and drinks served in Lika are similar

Figure 5.Site of Huluko (sketch by the researcher 2014).

to that of Dala ritual. Formal eating and drinking for relative and neighbors are usually arranged in days following the end of the cattle counting because they have to first serve the guests successfully. The feasts provided often used to compare this Lika ritual with similar feasts held in other districts or villages and have potential to affect the public standing of Likaawa and his relatives.

4.3. The Gimuwa Ritual

As already pointed out above, the Dala/Lika ceremony honors males. Even wife of Dala/Likaawa admires her husband during the cattle counting ceremonies albeit she does this, thereby making direct reference to woman behind him. But tradition of displaying cattle wealth in Wolaita has especial ceremony that is held in honor of wife or mother of Dala/Likaawa. This tradition is called Gimuwa. The Gimuwa takes place in major market during the weekday or weekend following the end of Dala/Lika ceremony. As elders remember, Gimuwa was performed during Lika ceremony. But, at current time Gimuwa is conducted during both Dala and Lika ceremonies reflecting an increased societal recognition of the role of women in wealth accumulation. Women contribute to both households and agricultural activities in the society. However, they were not treated as equal partners in decision and ownership of household wealth. Ironically, successful men who counted the cattle in the study areas recognize the early species of livestock that they owned were bought by the saving of women or by the gift that they got from their parents in the form of heifers or money. The informants told that there is now increasing understanding that strong and wise women are behind every Dalla/Likaawa. Women are now publically recognized during both Dalla and Lika ceremonies. This change in the Dalla and Lika practices has its own contribution in resurgence of the practices and increased interest to invest in livestock. In order to qualify for Gimuwa status, a woman has to exceed reproductive age limit. If wife of Dala/Likaawa is young and does not wish to get the status of Gimuwa, it is often given to his mother provided that she is alive.

The Gimuwa ceremony is similar in guest service, wearing and social participation to that of Dala ceremony. But the numbers of guests are limited albeit the numbers of observer are much greater than that of the Dala or Lika because the Gimuwa ceremony takes place at local market. A candidate of Gimuwa wears especial clothes named Kototuwa. She also put on ostrich feature at her head, Wogorwa at her face, Hirbbora at her hand, Gimo Birata at her foot that together symbolize her Gimua status. Being accompanied by horsewomen that include her daughters, friends and husband or sons, the candidate enters the market telling her great deeds, that of her relatives and friends. She also admires the courageous women as well as natural and social heritage of people at her village. As shown in Figure 6, leading her attendants, she crosses thousands of observers through the midst of the market. While the people in the market clap their hands, she rides the horses back and forth for some time. Finally, as shown in Figure 6, she has to break a large pot filled with a local drink called farso.

After breaking the pot, she comes down from the horse and seats in the assigned place to drink from the farso. Her son or husband takes the farso and gives it to her to drink; every attendant freely drinks it. The woman who gets Gimuwa status also distributes some of the money that she has saved to the people at the market, particularly to the poor. Finally, being accompanied by her attendants, she return home and seat for foods and drink prepared for them.

As shown in Figure 7, a woman who gets the Gimuwa status is highly respected in the community and she is always accompanied by her assistants in a major social occasion. According to the tradition she is not allowed to

Figure 6.Wife and mother of Zeleke, Gocho kebele (the mother was getting Gimuwa status); the pot filled with farso and later broken (adopted from the video originally taken by Paulos C. 2013, available at the Kindo Didaye Wereda Culture and Tourism Bureau).

Figure 7. A woman who got Gimuwa and her son Gufa who become Dalaawa, Sere (photos taken by the researcher 2014).

go to the market to buy and sell goods, albeit there is nothing that restricts a man who gets Dala/Lika status from going market. All buying and selling are carried out by her assistants who always accompany her in important social events like funerary ceremony. Disobeying social restriction is considered socially shameful act and even insulting; it may decrease her prestige. Due to social expectation associated with Gimuwa status, some young women often do not like to assume the status, albeit their contribution to the accumulation of cattle wealth as well as social prestige associated with the Gimuwa status.

4.4. Significance of the Dala, Lika, and Gimuwa Rituals

The Dala, Lika and Gimuwa ceremonies have multifaceted roles in Wolaita society. The knowledge associated with the cultural practices of cattle counting has a potential to generate new knowledge that can improve the life of the farmers. This sub section explores roles of the Dala, Lika and Gimuwa rituals.

4.4.1. Economic Role

Livestock and livestock associated cultural practices have greater roles in Wolaita. Livestock play significant roles in the lives of peoples in Wolaita in terms of livelihood, employment creation and social security. Cattle that are counted during Dala and Lika rituals are shared with poor farmers who otherwise unable to afford the cost of buying cows by themselves. The poor have some access to livestock through arrangements with the owners such as joint ownership and confinements with rich farmers. All of these arrangements are based on neighborhood, kinship ties, marriage bonds, church affiliations, and other social networks. They give opportunities for owning the animals. Shared ownership of cattle (also called Kota) is common because it provides a means for poorer farmers to own a live animal. Cattle greatly contribute to poor farmers to get access to oxen for labor, manure and milk. Livestock are also a source of cash to purchase fertile, seed and to cover other expenses. Livestock is also a source of cash for purchasing inputs and for hiring wage labour, and of milk and butter which is important for a healthy labour force. The Dala and Lika ceremonies involve expensive feasts that are crucial to the poor to get food through redistributive mechanisms that the rich shares some his/her wealth to the poor.

The Cattle counting rite has also other economic roles. Materials and food and drinks used during the Dala, Lika and Gimuwa ceremonies are mainly locally made and are indigenous resources of the people, creating employment opportunity. In absence of modern banks and limited presence of microfinance institutions in rural areas, investing on cattle has a greater contribution to the saving and generation of income in rural areas. Limited access to lands particularly at highlands means investing in cattle remain an important source of income. Thus it is not surprising to see considerable labour and other goods are invested to the maintenance of livestock.

Cattle ownership also serves as indicators of wealth. Rich farmers invest on cattle on selling grains as cattle provide not only subsistence but also they reproduce themselves multiplying the wealth of the owners. Some farmers believe that investing on livestock is better than putting their money on banks even with risks associated with owning livestock. The prices of cattle are always increasing due to high demands of the cattle.

4.4.2. Social Role

The owner of cattle may not be able to reap the full benefit of their investment. But cattle ownership has a lot of social importance and brings a greater prestige in Wolaita society. Cattle bring a great pride and joy in the life of the people. Farmers give cattle to their daughters during marriage exchange. Traditionally, cattle are slaughtered on an important ceremony and accidental death of cattle is mourned as like that of human beings. Some members of society sacrifice them for their ancestral spirit and to resolve bloodshed between individuals or groups. Fame and strength of a person is largely depends on the number of cattle or other livestock one owns. Thus every one especially at rural areas cherishes cattle keeping and values them above all other possession and aspires to become a person who excels in cattle wealth in order to get social prestige associated with it.

Accordingly, the Dala and Lika rituals have far greater significance in terms of social prestige. The practices associated with cattle also enhance social bonds and relationship due to crosscutting nature of shareholding. Share owing (Kota) which is based on reciprocal mutual self-interests of the shareholders bonds the rich and the poor. In other words, due to multiple ties there is low tension between shareholders. Cases of dispute that arise in shareholding are easily resolved through the intervention of elders, which is important to save time and money to the farmers. The fact that Dala and Lika practices have both individual and collective nature makes it suitable to satisfy the interests of both individuals and groups. The Dala, Lika and Gimuwa primarily honor individuals. They also promote healthy competition between individuals who wish to get the public recognition. However, individual honor is result of collective efforts as it bases collective contribution to its realization. The Dala/Likaawas are also now being recognized by the government as model farmers.

The Dala, Lika and Gimuwa ceremonies also are promoting social interaction between the farmers and marginalized groups in the society. In past occupational minorities such as craftsmen and slaves did not have money to invest on cattle. The so-called free farmers enjoyed the rights to own land and other resources. Craftsmen (Degela) and traditional musicians (Chinasha) occupied very marginal lands as their main income come through selling of the agricultural tools and household utensils to the farmers as well as from gift for their cultural contribution during various social events such as marriage and funeral ceremonies. The social and economic statuses of the craftsmen were largely unchanged until the 1975 land reform that ensured access to land for slaves and other occupational minorities. This change enabled them to save money and invest in livestock. At the current time, it is not uncommon to see individuals from traditionally marginalized groups conducting Dala and Lika rituals. The change in their economic status has greatly contributed not only to the changing attitude towards occupational minorities but also it has made Dala and Lika inclusive institutions that provide social prestige to every hardworking individual regardless of their social background.

It is worth noting that cattle counting rite was not the only means that brought social prestige to the farmers in the study area. Hunting was for example popular practice until the demise of the military (Derg) regime in 1991. The people made series of hunting (shankas) in order to kill a big wild animals like tiger, lion and elephant. The farmers made many hunting campaign under the leadership of individuals who excelled in killing wild animals. These individuals are called Gadawas. Gadawa is highly esteemed social status. Gadawa gets gifts from relatives and friends for the killing of animals. Meat product and hides or teeth of the wild animals have marginal benefit to the Gadawas. However, the social prestige he gets from others is far more important. He is remembered as great heroes by his friends in all social events. It is also not uncommon to see the hides and horns of wild animals at the tombs of known Gadawas near road sides in the study areas. As informants told, some Gadawas were even buried with the spears that they frequently use to kill wild animals. However, depletion of big animals and burning of forests during hunting as well as increased pressure upon the farmers by the government to develop and care for animals and environment have their own contribution to the renewed attention towards investing on cattle in order to gain multiple purposes associated with cattle counting ceremony.

4.4.3. Environmental Role

Contrary to some commonly held perception that livestock deteriorate the environment, they have a significant contribution to environment, particularly to soil fertility management. Study in other parts of Wolaita has clearly shown that access to cattle has a great contribution to soil fertility management [4] . Smallholder farmers who own a few livestock use their dung as organic fertilizers. Manure from animals plays a very important role for farming of their food crops. Enset which is staple food in Wolaita and among its neighbors usually requires a large quantity of organic fertilizers and thus animal dung had special attention than the cereal crops. Some farmers who do not have the capital to afford their own cattle, kept dry and pregnant cows and calves that belonged to other rich farmers people until calving or growing for the benefit of using the manure to fertilize their crops.

The Dala and Lika ritual sites have especial environmental roles. As shown in Figure 8, the enclosure aimed to count cattle grows as permanent trees and considered as sacred places and are untouchable. Every member of society realizes that that site need to be protected in order to remember the person and inspires new generation to work hard to get wealth and acquires associated social status. Hence the Dala and Lika practices contribute to environmental protection.

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

The findings of the study assert that the Wolaita people are able to resuscitate many aspects of their indigenous cultural practices, particularly the Dala, Lika and Gimuwa rituals. This is mainly because of relative cultural freedom that was introduced with decentralization in the country since 1990s. Decentralization has created a chance to various ethnic groups in the country to exercise cultural and political self-rule. This right along with

Figure 8.Dala site of Atumo Yaya, Chewukare Dala site of Kolaso Kasa, Zamo (photos taken by the researcher 2014).

abandoning of some traditional practices such as hunting of wild animals, discrimination against women and occupational minorities has made cattle counting rituals attractive means of achieving social prestige and status in rural areas. In other words, the Dala, Lika and Gimuwa rituals have greater significance to economic, social and environmental sustainability in rural areas.

It is now widely recognized that cattle rearing provide better alternative to household livelihood both in rural and urban areas, particularly on areas that have limited access to lands. Yet alienating traditional practices associated with livestock are more likely to distort the very aims of ensuring livelihood and protecting environment. It would also affect the identity of people who are closely associated with the culture of cattle counting rite. Hence, it is very important to consolidate the livestock associated traditions in the Wolaita Zone and beyond. Although there is some diseases that affects the health of animals in the study areas that the officials are widely expected to address, temptation of some individuals to achieve public recognition by adding cattle that are not their own during Dala/Lika cattle counting day needs serious attention. Cheating of such type has potential to spoil the Dala/Lika rite and risks their continued existence. The Wereda officials should formally work with elders in order as to eliminate malpractice that can damage the public position of the tradition. It is also important to encourage the farmers to further enhance elements in the Dala, Lika and Gimuwa ceremony that recognize the ecological values and gender equality as well.

Acknowledgements

I am very grateful to Dilla University for its financial support to me to carry out this study. I am also indebted to the Kindo Didaye Culture, Tourism and Communication Bureau and its staff for sharing with me a lot of information and materials necessary to the study. Furthermore, staff of Wolaita Zone Culture, Tourism and Communication Bureau had their own contribution in this study. Especial thanks goes to my informants in Chewukare and Kindo as well as staff of Wolaita Language Department in Wolaita Sodo University (Mr. Woldemariam Lisanu and his colleagues) who gave to me relevant data. I thank my family for their unreserved support to me.

References

- United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (2012) Report on Livestock Value Chains in Eastern and Southern Africa: A Regional Perspective, E/ECA/CFSSD/8/6, 8 November 2012, Addis Ababa.

- Berleant-Schiller, R. (1977) The Social and Economic Role of Cattle in Barbuda. Geographical Review, 67, 299-309. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/213724

- Moyo, S. and Swanepoel, F.J.C. (2010) Multifunctionality of Livestock in Developing Communities. In: Swanepoel, F.J.C., Streobel, A. and Moyo, S., Eds., The Role of Livestock in Developing Communities: Enhancing Multifunctionality, UFS and CTA, South Africa, 1-11.

- Data, D. (1997) Soil Fertility Management in Wolaita, Southern Ethiopia: An Anthropological Investigation. Farmers Research Project (FRP) Technical Pamphlet No. 14. Addis Ababa: Farm Africa.

- Chiatti, R. (1984) The Politics of Divine Kingship in Wolaita (Ethiopia), 19th and 20th Centuries. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

- Berhanu, B. (1995) Production Practices in Damo Woyde: A Case of Sura Koyo. MA Thesis in Social Anthropology, Addis Ababa University, Addis Ababa (Unpublished).

- Adugna, E. and Wagayehu, B. (2013) Analysis of Wealth and Livelihood Capitals in Southern Ethiopia: A Lesson for Policy Makers. Current Research Journal of Social Sciences, 5, 1-10.

- Asrat, A., Zelalem, Y. and Ajebu, N. (2013) Characterization of Milk Production Systems in and around Boditti, South Ethiopia. Livestock Research for Rural Development, 25. http://www.lrrd.org/lrrd25/10/ayza25183.htm.

- Steele, M.C. (1981) The Economic Function of African-Owned Cattle in Colonial Zimbabwe. Zambezia, IX, 29-48.

- Russel, N. (1998) Cattle as Wealth in Neolithic Europe: Where’s the Beef? In: Baily, Ed., The Archaeology of Value: Essays on Prestige and the Process of Valuation, BAR International Series No. 730.

- Herskovits, M.J. (1926) The Cattle Complex in East Africa. Ph.D. Thesis, Columbia University, New York.

- Mtetwa, R.M.G. (1978) Myth or Reality: The “Cattle Complex” in Southeast Africa, with Special Reference to Rhodesia. Zambezia, 6, 23-35.

- Poissonnier, N. (2010) Favorite Enemies―The Case of the Konso. In: Gabbert, E.C. and Thubouville, S., Eds., To Live with Others―Essays on Cultural Neighborhood in Southern Ethiopia, Köppe, Köln.

- Dietler, M. (2001) Theorizing the Feast: Rituals of Consumption, Commensal Politics and Power in African Contexts. In: Dietler, M. and Hayden, B., Eds., Feasts: Archeological and Ethnographic Perspectives on Food, Politics and Power, Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington DC and London, 65-114.

- J.L.P. (2013) Livestock: Meat and Greens. The Economist, December 31st. http://www.economist.com/blogs/feastandfamine/2013/12/livestock

- CSA, Central Statistical Agency of Ethiopia (2008) Summary and Statistical Report of the 2007 Population and Housing Census: Population Size by Age and Sex. Federal Republic of Ethiopia, Population Census Commission, with Support from UNFPA.

- Wana, W. (1998) Ya Wolaita Hizb Tarik. Berhanina Selam Printing Press, Addis Ababa.

- Yacob, C. (2004) Biography of Kawo (King) Tona Gaga, the Last King of Wolaita (In Ethiopia). BED Thesis, Debub University, Hawassa.

- Data, D. (2005) Christianity and Spirit Mediums: Experiencing Post Socialist Religious Freedom in Southern Ethiopia. Working Paper 75, Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology, Halle.

- Tilahun, M. (2014) Ceremony of Liqo under the Culture of Livestock Counting Festivity: The Case of Demba Gofa District. BA Thesis, Dilla University, Dilla.