Paper Menu >>

Journal Menu >>

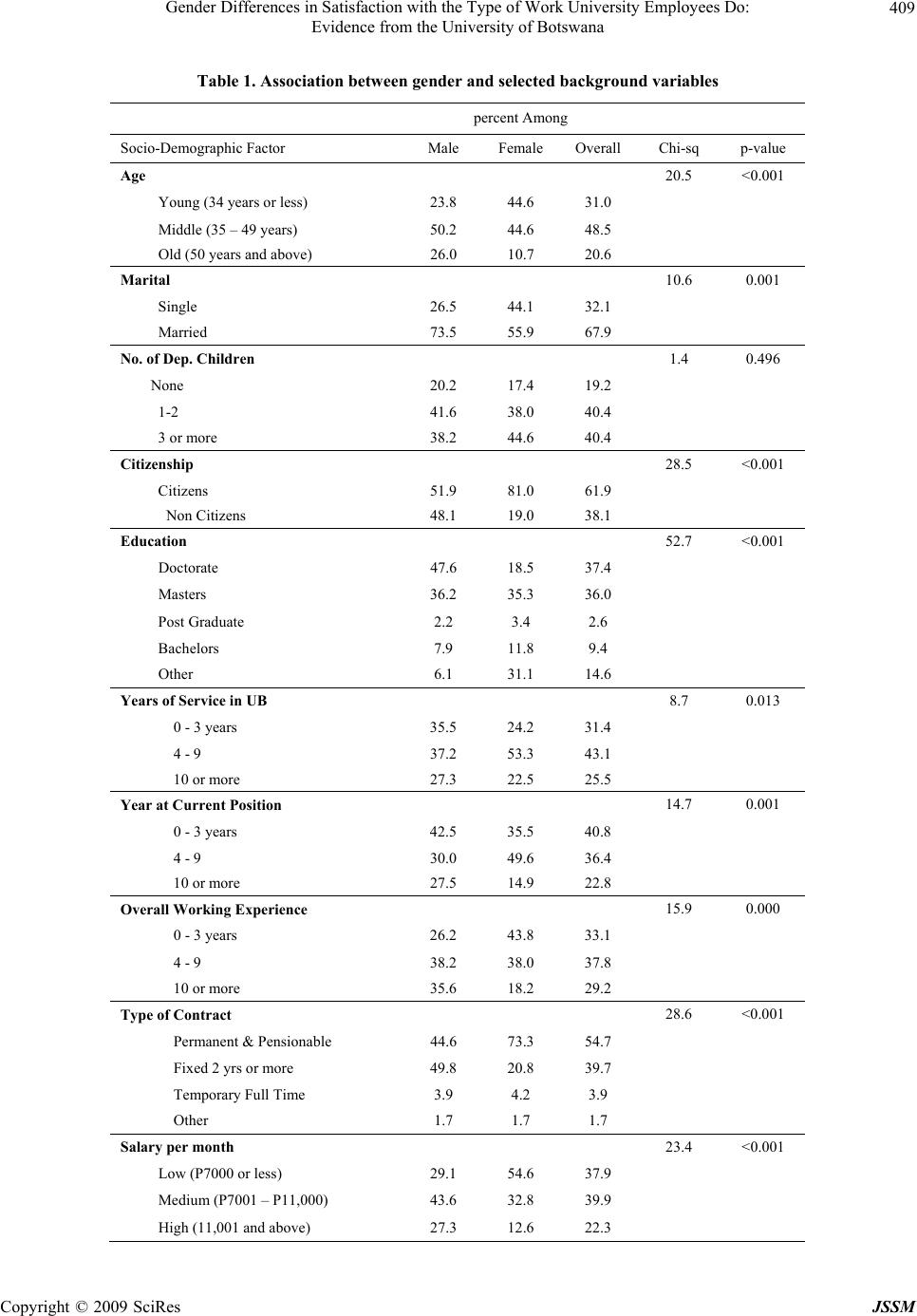

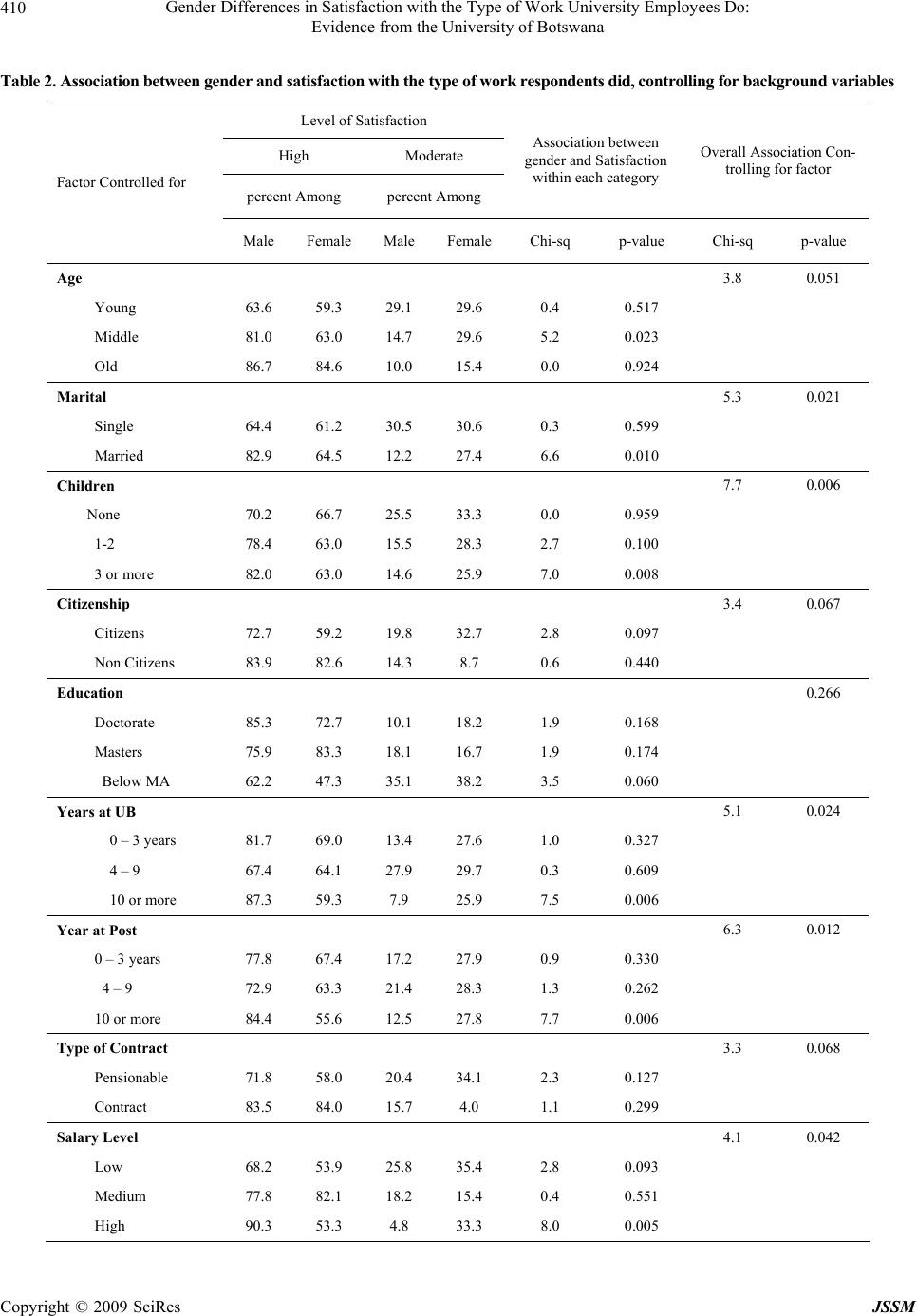

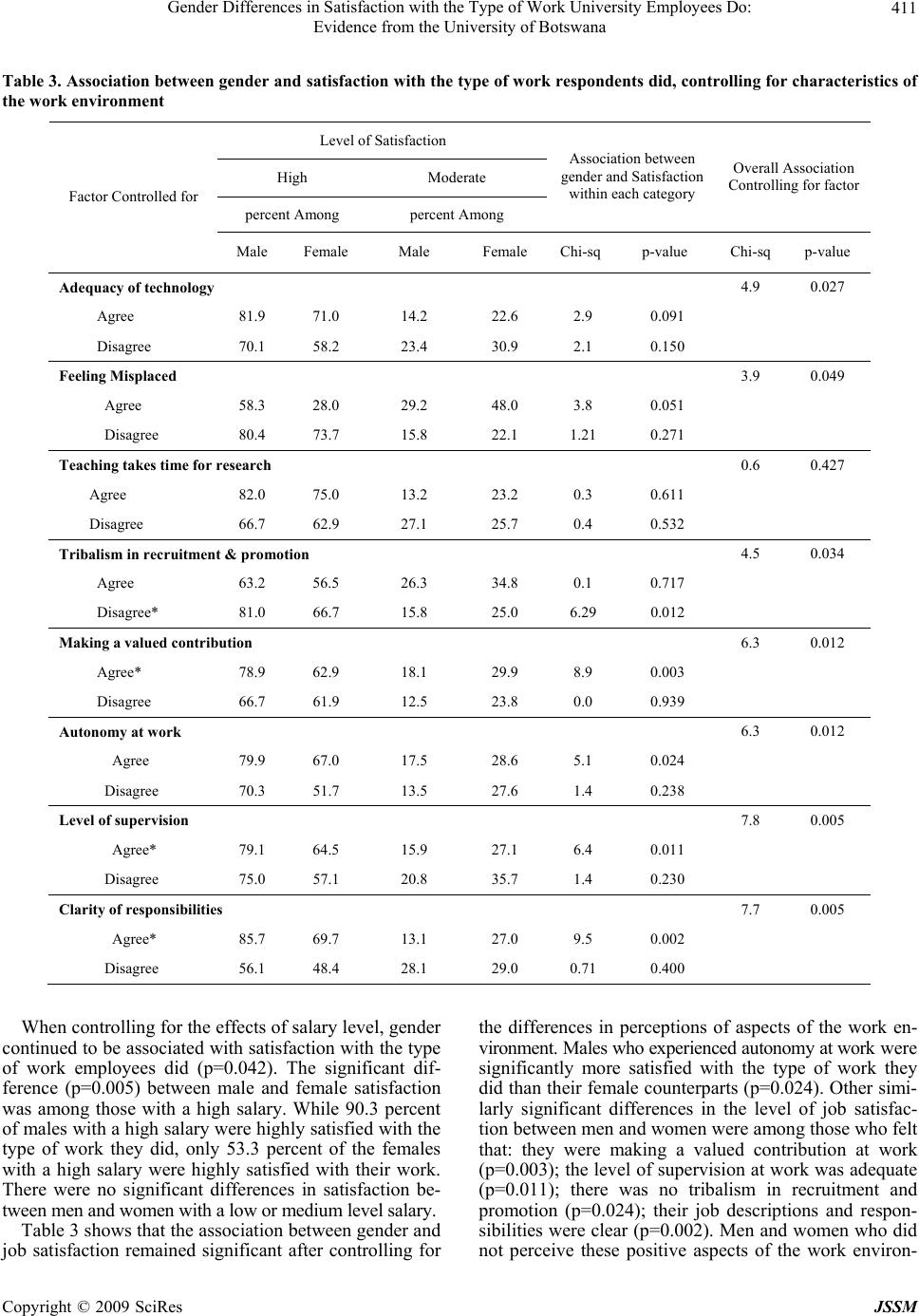

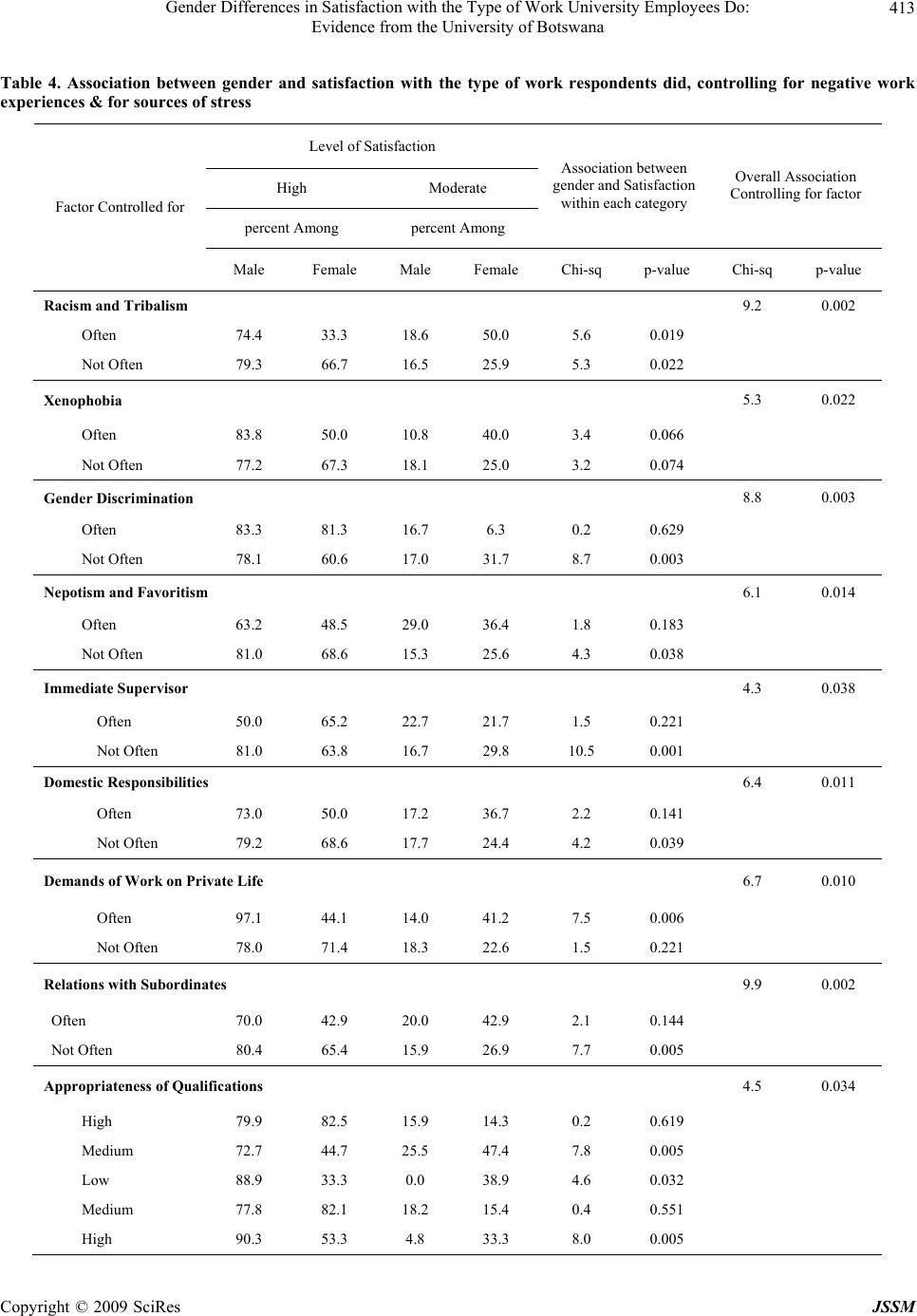

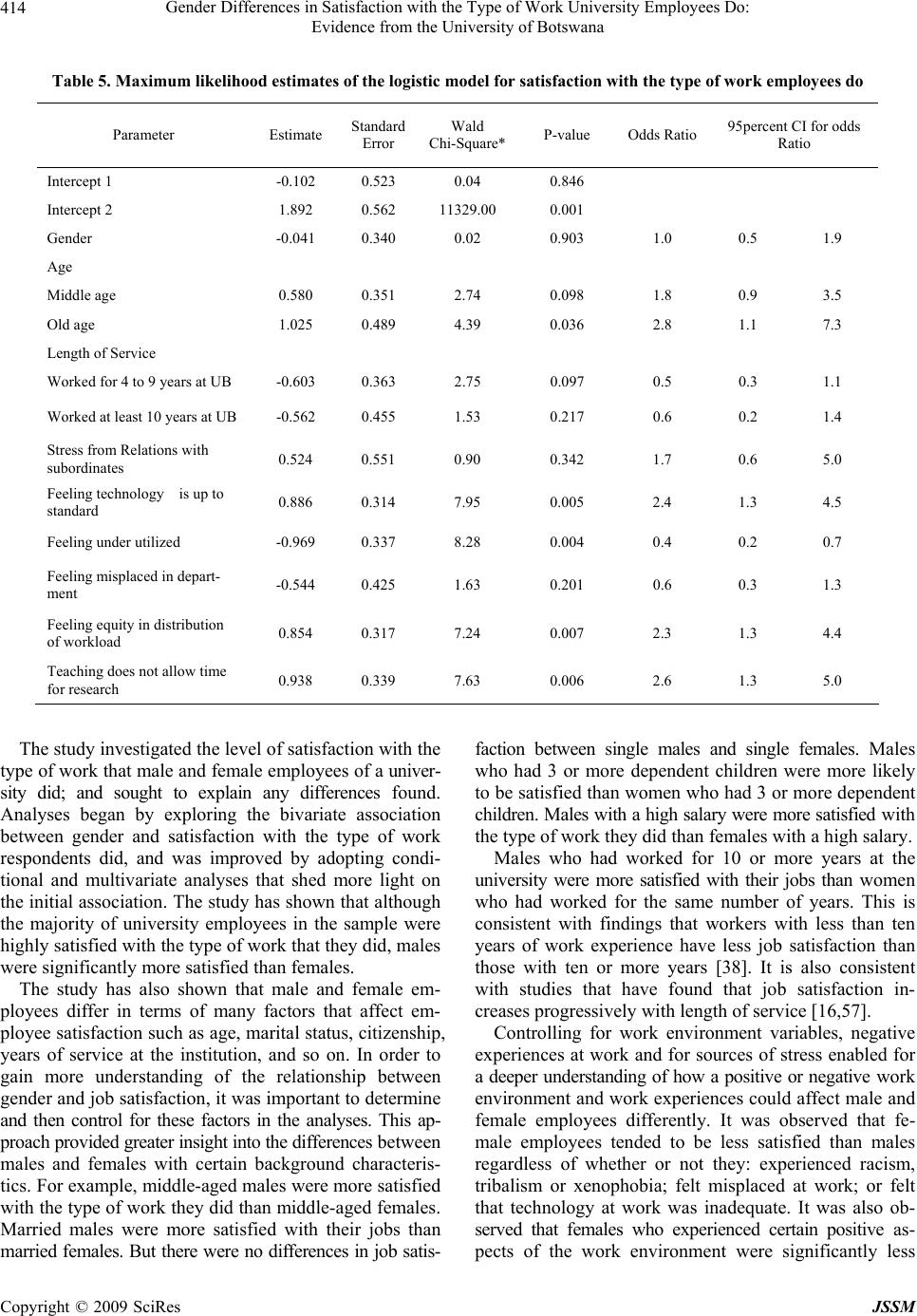

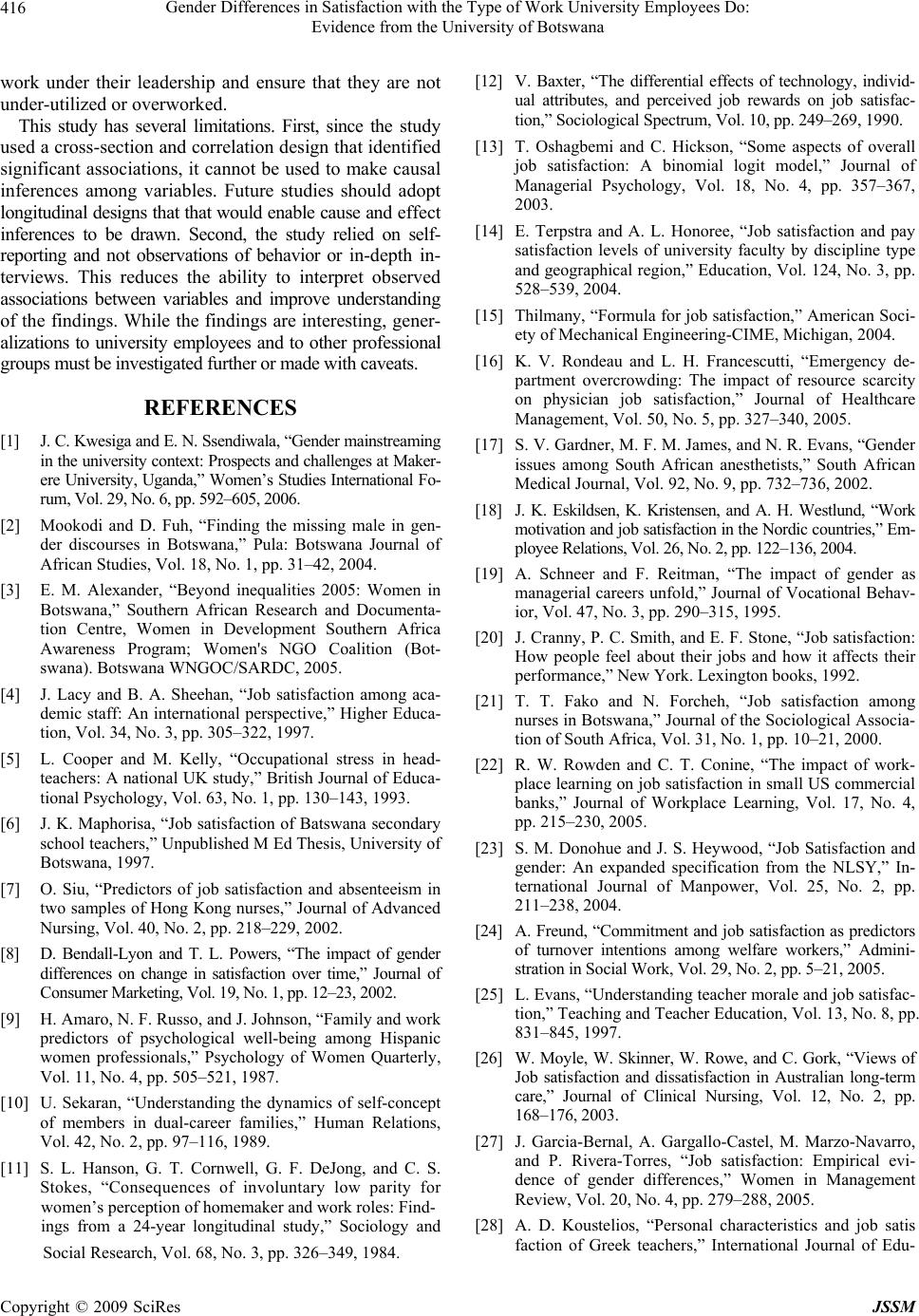

J. Service Science & Management, 2009, 2: 404-417 doi:10.4236/jssm.2009.24049 Published Online December 2009 (www.SciRP.org/journal/jssm) Copyright © 2009 SciRes JSSM Gender Differences in Satisfaction with the Type of Work University Employees Do: Evidence from the University of Botswana Thabo T. Fako1, Stoffel R. T. Moeng1, Ntonghanwah Forcheh2 1Department of Sociology, University of Botswana, Botswana; 2Department of Statistics, University of Botswana, Botswana. Email: fakott@mopipi.ub.bw, Moengsrt@mopipi.ub.bw, forchehn@mopipi.ub.bw Received July 15, 2009; revised August 27, 2009; accepted October 3, 2009. ABSTRACT The study investigated the extent to which male and female employees of a University differ in various attributes and attitudes and in the level of satisfaction with the type of work they do, and further established factors that might help explain these differences. A stratified random sample of 360 academic and administrative staff of the University of Botswana was collected. Findings indicate that differences between males and females in the level of satisfaction were due to certain negative work experien ces such as gender discrimina tion, triba lism and racism, nepotism and favoritism, and due to certain sources of stress from the immediate supe rvisor, demands of work o n private life and from domestic responsibilities. These negative experiences contributed to lower levels of satisfaction among women than among men. Considering all factors that might explain different job satisfaction among employees at a university, five attributes stood out as significant, namely: belonging to an older age group; understanding the competing demands of teaching and research responsibilities; taking advantage of technological advancement at work; perceiving equity in the distri- bution of the workload; feeling that there was always enough to do at work. Keywords: Job Satisfaction, Gender, University Employees, Multivariate Analysis, Botswana 1. Introduction The main objective of this study was to determine w he the r or not there were significant gender differences in the level of satisfaction with the type o f work that e mployees of a university do. The second objective was to deter- mine whether or not the difference (if it exists) in satis- faction with the type of work that male and female em- ployees of a university do could be explained by other factors within and outside the work environment. Finally we sought to identify key attributes th at could be used to predict the likelihood of job satisfaction among univer- sity employees. In recent years, there has been a consistent call at in- ternational, regional, national and institutional levels for gender to be integrated into all decision-making proc- esses [1,2]. In recognition of the importance of gender in the workplace, the University of Botswana established the Gender Policy Programme Committee (GPPC) to create gender awareness and facilitate the incorporation of g end er into policies, academic programs and administrative pr oce - dures [3]. However, systematic empirical research that s e ek s to understand gender differences and inform policy deci- sions in a university environment is still at its infanc y. Several studies have reported higher levels of job sat- isfaction among male employees compared to female employees. In a study of academics across eight nations, [4] found that male academics tended to be more satis- fied with most aspects of their jobs than female academ- ics. Cooper and Kelly [5] found that significantly more female head teachers in secondary and higher education schools suffered job dissatisfaction than their male coun- terparts. In Botswana, Maphorisa [6] found that male teach- ers in secondary schools reported higher levels of job satisfaction than females with the same length of teach- ing experience. It has been argued that male workers are more likely to be satisfied with their jobs than female workers [7] espe- cially in organizations where males have more opportu- nities for advancement or where females are the last to be employed and the first to be fired [8]. In many societies females still generally face greater challenges of access to education, access to mentors and sponsors, and de- mands related to home and family responsibilities as well  Gender Differences in Satisfaction with the Type of Work University Employees Do: 405 Evidence from the University of Botswana as lack of female role models, all of which could lead to lower job satisfaction. Amaro et al. [9] found that having children was nega- tively associated with personal and professional satisfac- tion among Hispanic women professionals, managers and business owners. Sekaran [10] found that men had higher levels of job satisfaction because they spent less time in childcare and household activities and therefore, had more discretionary time to spend on job relat ed acti vities. Women on the other hand, experienced significantly lower levels of satisfaction when they spend greater amounts of dis- cretionary time on job related activities as opposed to childcare and household activities. Hanson and associates [11] found that rural women with a smaller number of children who devoted resources not needed for child rearing to attaining occupational goals had higher levels of job satisfaction. Demands from both the home and the work environment are likely to affect the performance and satisfaction of male and female employees differently. Given the patriarchal system in which married female employees may have less time to spend on professional self development and research and subsequent publica- tion in favor of domestic activities, it would seem that the scales are tipped in favor of male output, career prospects and job satisfaction. While most of the literature reviewed suggests that men are more likely to be satisfied with their jobs than women in most occupations, a few studies have found females to be more satisfied with their work than males [12–15] For example, Rondeau [16] found that female physicians were more satisfied with their jobs than their male counterparts. Gardner et al. [17] found that female anaesthetists in South Africa were more satisfied with their jobs than their male counterparts. Other studies have found no differences in the level of job satisfaction between men and women [18,19]. 2. Conceptual Framework Job satisfaction is one of the most widely discussed and enthusiastically studied constructs among scholars in the behavioral and organizational sciences [20]. By the early 1970’s, more than 4,000 articles had been published on the topic [21]. Yet, job satisfaction is among the least understood phenomena in organizations today [22]. The concept of job satisfaction consists of at least three dimensions: 1) a subjective perception of the job by the individual; 2) the degree to which the job is perceived as pleasurable; 3) the difference between what employees want out of a job and what they actually get from the job. As a subjective perception, job satisfaction represents a worker’s own evaluation of his or her job [23]. It is ho w the worker feels about his or her work [22] or about various facets of the work environment [24]. Job satisfaction is largely a present-oriented response to the current situa- tion or conditions at work [25]. It reflects favorable or unfavorable views employees have toward the work itself [26] and aspects of work such as pay, supervision, bene- fits and so on [15]. It is simply the degree to which a person feels satisfied by their job [27]. Job satisfaction has also been defined as a pleasurable or positive emotional reaction and state of mind resulting from the appraisal of one’s job or job experiences [28,29], the tasks one has to perform at work, as well as the physical and social conditions of the workplace [30,31]. It is a positive emotional and cognitive attitude that results from the pleasure a worker derives from component facets of the job [32]. It consists of positive feelings at the end of the job [33], and reflects the degree to which individuals like their jobs [34,35] or simply enjoy their occupations [36], experience a sense of self-growth and accomplish- ment in their work and would choose the same job again if given an opportunity [37]. Job satisfaction has also been defined in terms of dis- crepancies between desires and achievements at work. It is as a combination of cognitive and affective reactions to the differential percep tions of what an employee wants to receive compared with what he or she actually receives [38]. It is a function of the perceived relationship be- tween what one wants from one’s job and what one per- ceives the job offers [39], or “what is expected (or de si r ed) and what is received”. Job satisfaction is determined by th e difference between the amount of some valued outcome that a person receives and the amount of the outcome he feels he should receive [20]. If one expects little and gets little, they would be satisfied. Similarly, if one expects a lot and gets a lot, they would be satisfied. If one expected a lot and got little, they would be dissatisfied. It has been reported that many employees are not sat- isfied with the type of job they d o [26,40]. Kristiina [41] found that six out of ten workers were planning to leave their current employer for other pursuits within the next two years. In Denmark, Pors and Johannsen [42] found that 25 percent of library employees left their employ- ment before serving three years due mainly to dissatis- faction with their jobs. Dissatisfying job conditions mo- tivate employees to engage in behaviors aimed at reduc- ing frustration and anxiety, and at improving working con- ditions, the standard of living an d equality [43]. Dissatis- fied workers may be disruptive, go on strike and may even resort to violence and cause physical harm to other employees [44]. 3. The Research Problems It is known that low levels of job satisfaction can have a negative effect on morale [45], employee relations [26], employee performance, organizational functioning [46], organizational efficiency and productivity. Low job sat- isfaction or outright dissatisfaction with a job is likely to Copyright © 2009 SciRes JSSM  Gender Differences in Satisfaction with the Type of Work University Employees Do: 406 Evidence from the University of Botswana evoke an array of negative and potentially damaging per- sonal and professional consequences [28] such as frustra- tion, deterioration of mental and physical health [47], withdrawal, absence, lateness, sickness, accidents [26], intra–organization al conflict [47], thinking abou t quitting and retirement [48], examining the costs and benefits a sso - ciated with leaving a job, and labour turnover [49]. In- tentions to quit can be very costly to organizations [50]. A recent “Ernst & Young” survey calculated that the cost of replacing a high-level employee may be as much as 150 percent of the departing employee's salary [41]. In educational institutions pressures from academic and organizational reform, working with challenging stu- dents, increased staff–student ratios, increased administra- tive duties, time constraints, eco nomic difficulties, dwin- dling financial resources from both internal and external sources, funding shortages, etc, increase the level of stress and reduce job satisfaction [51]. In Africa, repres- sive regimes, poor management, mediocrity and com- placency and have led to the deterioration of universities and tertiary education in general. For more than two decades, universities and other educational institutions in Africa have, to varying degrees, experienced overstr etched financial and physical resources, deterioration of existing facilities and infrastructure, lack of a maintenance culture, insipient decay in the fabric of institutions and a decline in quality and excellence [52]. These conditions are bound to strain human resources and result in low levels of job satisfaction among employees. In addition, advan ces in information techno logies have resulted in information overload du e to the increased use of e-mail and the Internet. While technology is desired and can make work more interesting and satisfying, it has also meant that workers are never really far from the of- fice, and can be reached anytime on cell phones. Those who fail to catch up with technological develop ments run the risk of frustration and poor performance at work, which may lead to reduced job satisfaction [47]. Given the importance of job satisfaction on employee productivity, it is necessary to periodically take a snap shot of the extent of job satisfaction among employees of major organizations, especially after major changes are introduced in the organization. At the University of Bot- swana, two such major changes were the restructuring of the administrative system and the restructuring of the academic system through the introduction of semesteri- sation in 2002. It is therefore, opportune to investigate the extent to which employees of a major national insti- tution are satisfied with their job, and to determine the role of gender as a key factor. 4. Methods The target population for the study comprised of all em- ployees with officially allotted office space. This included all academic staff, all managerial (executive, senior and middle level administrative) staff including the secretar- ies and support staff of sections and departments whose names appeared in the university telephone directory. Th us the lower end of the hierar chy (who did not appear in th e telephone directory) such as messengers, gardeners, and other junior level staff, were not included in the study. All 1460 staf f members were identified within this study population of which 928 worked in academic faculties while the remaining 532 (36.4%) worked in non-academic units. For sampling purposes, the study population was strati- fied into enumeration units. The average size of the enu- meration units was 11 employees. Broadly, each enumera- tion unit was a well defined administrative or academic department with a staff establishment of approximately 11 employees (such as the Department of Sociology), a combination of small Departments that had substantially less than 11 employees (such as Educational Technology and Home Economics) or a sub-division of a larger de- partment that had substantially more than 11 employees (such as the Department of English). The study targeted 25 percent of employees, which translated into approximately 3 staff members from each Enumeration Unit. The 10 to 12 staff members within each unit were numbered sequentially and simple random sample approach used to select three staff members from each unit. In order to minimize non-response, all staff members were formerly notified of the study, and its benefit to them, and two weeks were allowed for data collection, with follow-ups made during the two weeks. 5. Measurement of Variables A questionnaire was used to r ecord a variety of informat i on about employee attributes and work-related attitudes and experiences. The main variable of our research interest, “satisfaction with the type of work that employees did”, was measured by asking each respondent to rate the level of satisfaction with the type of work that he or she did on a scale from zero to 10. Zero represented the lowest level of satisfaction and 10 represented the highest level of satisfaction. For analysis, the level of satisfaction with the type of work employees did was divided into three ordinal categories: 1=High, 2=Moderate and 3=Low, which corresponded to scores of 7-10, 4-6 and 0-3 respectively. Background variables were measured by appropriately phrased questions on respondent’s gender, age, number of dependent children, level of education, type of con- tract, years of service, etc. Negative experiences at work were measured by asking respondents to indicate on a scale from zero to 10 how often they experienced tribal- ism and racism, xenophobia, gender discrimination, nepo- tism and favoritism. Stress from different sources was measured by asking respondents to indicate on a scale from zero to 10 how often they experienced stress from i m- Copyright © 2009 SciRes JSSM  Gender Differences in Satisfaction with the Type of Work University Employees Do: 407 Evidence from the University of Botswana mediate supervisors, domestic responsibilities, demands of work on private life, relations with subordinates, and from the appropriateness of their qualifications. Various aspects of the work environment were measured by ques- tions asking respondents to indicate, on a four-point scale ranging from strongly agree to strongly disagree, the ex- tent to which: technology at work was up to date; they felt misplaced in their job; they experienced competing and conflicting work demands; there was tribalism in re- cruitment and promotion; they made a valued contribu- tion at work; there was autonomy at work; the level of supervision was adequate; and there was clarity in their job description or responsibilities. For purp oses of analy- ses each of these variables was recoded into an ordinal variable, as shown in attached tables. 6. Data Analysis Methods Preliminary analysis was directed at determining basic characteristics of the selected employees as well as de- termining the ex tent to which they were satisfied with the type of work that they did. Chi-squared tests of associa- tion were used to investigate whether there were statisti- cally significant1 differences between male and female employees with respect to their background characteris- tics, work-context experiences, the chemistry of social relations at work, sources of stress and satisfaction with the type of work that they did. Further analysis were aimed at investigating whether the association between gender and satisfaction with the type of work employees did depended on, and could be explained by other factors. For these analyses, variables that were found to have a statistically significant rela- tionship with gender were introduced one at a time as controls for the bivariate relationship between gender and satisfaction with the type of work employees did. The use of controls was important because some of the fac- tors that on their own could explain differences in em- ployee’s level of satisfaction were also associated with gender. Suppose for example that older employees tend to be more satisfied than younger employees, but more females tend to be younger employees than males. Then in order to determine the extent to which satisfaction depends on gender, one would need to exclude the medi- ating effect of age on satis fac t i on. One way of doing so (i.e. adjusting or controlling for age) is to do different comparisons of males and females within younger respondents and within older respondents (within the age variable) and for all respondents combined (overall). The Mantel-Haenszel chi-square test of asso- ciation [53] was employed to assess whether the associa- tion between gender and satisfaction with the type of w ork employees did still remained statistically significant when controlling for significant background variables, work- context variables and variables measuring the chemistry of relations at work. The decision as to whether an asso- ciation was statistically significant was measured using the likelihood (the p-value of the test) that the null hy- pothesis of no association could be true in the general population. The smaller the p-v alue is, the lower the like- lihood that the null hypo thesis is true and vice versa. The traditional cut-off of 5 percent (p=0.05) was used. A model for predicting the probability that an em- ployee would be satisfied given their gender, while con- trolling for the moderating factors such as age, marital status, etc. was developed. Competing models were the ordinal regression and a proportional odds model of the logistic family [54,55], since the dependent variable, “satisfaction with type of work employees do” had three ordinal levels (high, moderate and low). The proportional odds model involved recoding the dependent variable into two dichotomous variables, Y1 and Y2. Where, for a given employee, Y1 equ al to 1 if the employee’s level of satisfaction was high and 0 other- wise; and Y2 equal to 1 if the employee’s level of satis- faction was high or moderate and 0 if it was low. Hence the models provided a framework for comparing em- ployees who were highly satisfied with those who were not, and also comparing employees who were not satis- fied (low level of satisfaction) with those that were satis- fied (high or medium level of satisfaction). The fitted model, as implemented in SAS Version 8, produces separate intercept parameters and the same regression parameters for the two logits2. The model results include estimates of the coefficients of each factor level in the model and their standard error as well as corresponding Wald statis- tic for determining the level of significance of the factor level, the level of significance of the Wald statistics, the odds ratio and its 95% confidence interval. The odds ratio is particularly useful in comparing the relative like- lihood that an employee with a given attribute would be satisfied relative to an employee with a reference attrib- uted. For example, the odd-ratio corresponding to “mid- dle age”, gives the likelihood that a middle aged respon- dent would be satisfied compared to a young employee (the reference category for age), when all other factors in the model are considered. The stepwise variable selection procedure with backward elimination was used to derive the most parsimonious model. The adequacy and good- ness of fit of the fitted models were evaluated using the score test and the global Wald statistics respectively. 6.1 Preliminary Findings The sample consisted of 360 university employees. There were 233 (65.8%) males and 121 (34.2%) females who indicated their gender. Out of 355 who indicated their age, 20.6% were categorized as old (50 years or older), 1Subsequently, a “significant difference” shall imply “a statistically sig- nificant difference” in this paper. Copyright © 2009 SciRes JSSM  Gender Differences in Satisfaction with the Type of Work University Employees Do: Evidence from the University of Botswana Copyright © 2009 SciRes JSSM 408 48.5% were categorized as middle aged (35-49 years) and 31.0% were categorized as young (35 years or younger). Many respondents (46.1%) had one or two dependent children, 34.4% had three or more dependent children whil e 19.4 % had no dependent chil dren. Most respondents (57.9%) were employed on a per- manent basis while the remainder (42.1%) were employed on renewable contract (mostly for two years). Respon- dent’s educational background included 37.4% with a doctorate degree, 36.0% with a Masters degree and 26.6% with qualifications below a Masters degree (i.e., post graduate diploma and Bachelor’s degree or lesser quali- fications). The majority of respondents (84.4%) worked in the six academic Faculties (Business, Education, En- gineering, Humanities, Science and Social Science) and 74.4% described their current responsibilities at work as a combination of teaching, research, service and some administrative duties. The mean rating for satisfaction with type of work re- spondents did w as 7.29 (median=8). Wh en level of satis- faction with the type of work employees did was broken into three ordinal categories, 73.0% of respondents were classified as being highly satisfied with the type of work they did, 21.0% as moderately satisfied and only 6.0% were classified as having a low level of satisfaction with the type of work they did. 6.2 Association between Gender and Other Socio-Demographic Factors Bivariate analysis began with the determination of whether male and female employees in the sample dif- fered in terms of their background characteristics (socio- economic and demographic). The results (see Table 1) indicate that males and females differed significantly in many socio-economic and demographic characteristics. It was found that males were significantly older than females (p<0.001). A significantly higher proportion (73.5%) of males was married, compared to 55.9 percent of females. By contrast, 81.0 percent of the females were citizens compared with about 51.9 percent of the males. A significant proportion of males had acquired higher educational qualifications than females (p<0.001). A high percentage of the males (83.8%) had acquired a Masters or doctorate degree compared to 53.7 percent of the females. Other significant differences between men and women were observed regarding number of years working for the university, number of years working in the current position, type of contract, and salary level. The extent of satisfaction among males was signifi- cantly higher than that among females difference was further confirmed (p=0.014) when the level of satisfac- tion was broken into the three ordinal categories used throughout the study. While 78.1 percent of the males were highly satisfied with the type of job they did, 63.6 percent of the females were highly satisfied with the type of work they did. Th is indicated that males were more highly satisfied with the type of work they did than females. 6.3 Bivariate Association between Gender and Satisfaction After identifying background factors that had a statisti- cally significant relationship with gender, we adjusted for their possible effects on the relationship between gender and job satisfaction by including each one of th em as a control or mitigating variable. Table 2 shows a summary of results. When controlling for age, a statistically significant as- sociation between gender and satisfaction with the type of work was observed only among middle-aged employ- ees (p=0.023). While 81.0 percent of middle-aged males were highly satisfied with the type of work they did, a significantly lower percentage (63.0%) of middle-aged females were highly satisfied. The lack of any gender differences in satisfaction among younger or older respondents meant that when ad- justing for age, the association between gender and satis- faction became non-significant statistically (p=0.051). When controlling for the effects of marital status, gender continued to be associated with satisfaction with the type of work employees did (p=0.021). However, the significant difference was found only between married respondents (p=0.010) and not among single respondents (p=0.599). The results show that while 82.9 percent of married males were highly satisfied with the type of work they did, a significantly lower proportion (64.5%) of married females were highly satisfied. Similarly, males were more likely to be highly satisfied than fe- males when controlling for number of dependent children. The difference was between men and women who had three or more children (p=0.008). When controlling for years of service to the univer- sity, the relationship between gender and satisfaction with the type of work employees did remained signifi- cant (p=0.024). The significant difference between male and female respondents (p=0.006) was found among those with 10 or more years of service. There were no significant differ- ences between male and female respondents who had worked for nine or fewer years at the university. Simi- larly, a significant difference between males and females (p=0.006) was found among th ose with 10 or mor e years n their current position in the university. 2Multiple logistic regression is similar to the usual multiple linear re- gression model, but is used when the dependent variable is dichoto- mous instead of continuous. i  Gender Differences in Satisfaction with the Type of Work University Employees Do: 409 Evidence from the University of Botswana Table 1. Association between gender and selected background variable s percent Among Socio-Demographic Factor Male Female Overall Chi-sq p-value Age 20.5 <0.001 Young (34 years or less) 23.8 44.6 31.0 Middle (35 – 49 years) 50.2 44.6 48.5 Old (50 years and ab o ve ) 26.0 10.7 20.6 Marital 10.6 0.001 Single 26.5 44.1 32.1 Married 73.5 55.9 67.9 No. of Dep. Children 1.4 0.496 None 20.2 17.4 19.2 1-2 41.6 38.0 40.4 3 or more 38.2 44.6 40.4 Citizenship 28.5 <0.001 Citizens 51.9 81.0 61.9 Non Citizens 48.1 19.0 38.1 Education 52.7 <0.001 Doctorate 47.6 18.5 37.4 Masters 36.2 35.3 36.0 Post Graduate 2.2 3.4 2.6 Bachelors 7.9 11.8 9.4 Other 6.1 31.1 14.6 Years of Service in UB 8.7 0.013 0 - 3 years 35.5 24.2 31.4 4 - 9 37.2 53.3 43.1 10 or more 27.3 22.5 25.5 Year at Current Position 14.7 0.001 0 - 3 years 42.5 35.5 40.8 4 - 9 30.0 49.6 36.4 10 or more 27.5 14.9 22.8 Overall Working Experience 15.9 0.000 0 - 3 years 26.2 43.8 33.1 4 - 9 38.2 38.0 37.8 10 or more 35.6 18.2 29.2 Type of Contract 28.6 <0.001 Permanent & Pensionable 44.6 73.3 54.7 Fixed 2 yrs or more 49.8 20.8 39.7 Temporary Full Time 3.9 4.2 3.9 Other 1.7 1.7 1.7 Salary per month 23.4 <0.001 Low (P7000 or less) 29.1 54.6 37.9 Medium (P7001 – P11,000) 43.6 32.8 39.9 High (11,001 and above) 27.3 12.6 22.3 Copyright © 2009 SciRes JSSM  Gender Differences in Satisfaction with the Type of Work University Employees Do: 410 Evidence from the University of Botswana Table 2. Association between gender and satisfaction with the type of work respondents did, controlling for background variables Level of Satisfaction High Moderate percent Among percent Among Association between gender and Satisfaction within each category Overall Association Con- trolling for factor Factor Controlled for Male Female Male FemaleChi-sq p-value Chi-sq p-value Age 3.8 0.051 Young 63.6 59.3 29.1 29.6 0.4 0.517 Middle 81.0 63.0 14.7 29.6 5.2 0.023 Old 86.7 84.6 10.0 15.4 0.0 0.924 Marital 5.3 0.021 Single 64.4 61.2 30.5 30.6 0.3 0.599 Married 82.9 64.5 12.2 27.4 6.6 0.010 Children 7.7 0.006 None 70.2 66.7 25.5 33.3 0.0 0.959 1-2 78.4 63.0 15.5 28.3 2.7 0.100 3 or more 82.0 63.0 14.6 25.9 7.0 0.008 Citizenship 3.4 0.067 Citizens 72.7 59.2 19.8 32.7 2.8 0.097 Non Citizens 83.9 82.6 14.3 8.7 0.6 0.440 Education 0.266 Doctorate 85.3 72.7 10.1 18.2 1.9 0.168 Masters 75.9 83.3 18.1 16.7 1.9 0.174 Below MA 62.2 47.3 35.1 38.2 3.5 0.060 Years at UB 5.1 0.024 0 – 3 years 81.7 69.0 13.4 27.6 1.0 0.327 4 – 9 67.4 64.1 27.9 29.7 0.3 0.609 10 or more 87.3 59.3 7.9 25.9 7.5 0.006 Year at Post 6.3 0.012 0 – 3 years 77.8 67.4 17.2 27.9 0.9 0.330 4 – 9 72.9 63.3 21.4 28.3 1.3 0.262 10 or more 84.4 55.6 12.5 27.8 7.7 0.006 Type of Contract 3.3 0.068 Pensionable 71.8 58.0 20.4 34.1 2.3 0.127 Contract 83.5 84.0 15.7 4.0 1.1 0.299 Salary Level 4.1 0.042 Low 68.2 53.9 25.8 35.4 2.8 0.093 Medium 77.8 82.1 18.2 15.4 0.4 0.551 High 90.3 53.3 4.8 33.3 8.0 0.005 Copyright © 2009 SciRes JSSM  Gender Differences in Satisfaction with the Type of Work University Employees Do: Evidence from the University of Botswana Copyright © 2009 SciRes JSSM 411 Table 3. Association between gender and satisfaction with the type of work respondents did, controlling for characteristics of the work environ ment Level of Satisfaction High Moderate percent Among percent Among Association between gender and Satisfaction within each category Overall Association Controlling for factor Factor Controlled for Male Female Male Female Chi-sq p-value Chi-sq p-value Adequacy of technology 4.9 0.027 Agree 81.9 71.0 14.2 22.6 2.9 0.091 Disagree 70.1 58.2 23.4 30.9 2.1 0.150 Feeling Misplaced 3.9 0.049 Agree 58.3 28.0 29.2 48.0 3.8 0.051 Disagree 80.4 73.7 15.8 22.1 1.21 0.271 Teaching takes time for research 0.6 0.427 Agree 82.0 75.0 13.2 23.2 0.3 0.611 Disagree 66.7 62.9 27.1 25.7 0.4 0.532 Tribalism in recruitment & promotion 4.5 0.034 Agree 63.2 56.5 26.3 34.8 0.1 0.717 Disagree* 81.0 66.7 15.8 25.0 6.29 0.012 Making a valued contribution 6.3 0.012 Agree* 78.9 62.9 18.1 29.9 8.9 0.003 Disagree 66.7 61.9 12.5 23.8 0.0 0.939 Autonomy at work 6.3 0.012 Agree 79.9 67.0 17.5 28.6 5.1 0.024 Disagree 70.3 51.7 13.5 27.6 1.4 0.238 Level of supervision 7.8 0.005 Agree* 79.1 64.5 15.9 27.1 6.4 0.011 Disagree 75.0 57.1 20.8 35.7 1.4 0.230 Clarity of responsibilities 7.7 0.005 Agree* 85.7 69.7 13.1 27.0 9.5 0.002 Disagree 56.1 48.4 28.1 29.0 0.71 0.400 When controlling for the effects of salary level, gender continued to be associated with satisfaction with the type of work employees did (p=0.042). The significant dif- ference (p=0.005) between male and female satisfaction was among those with a high salary. While 90.3 percent of males with a high salary were h ighly satisfied with the type of work they did, only 53.3 percent of the females with a high salary were highly satisfied with their work. There were no significant differences in satisfaction be- tween men and women wi th a low or m edium le vel sal ary. Table 3 shows that the association between gender and job satisfaction remained significant after controlling for the differences in perceptions of aspects of the work en- vironment. Males who exp erien ced autono my a t work were significantly more satisfied with the type of work they did than their female counterp arts (p=0.024). Other simi- larly significant differences in the level of job satisfac- tion between men and women were among those who fel t that: they were making a valued contribution at work (p=0.003); the level of supervision at work was adequate (p=0.011); there was no tribalism in recruitment and promotion (p=0.024); their job descriptions and respon- sibilities were clear (p=0.002). Men and women who did not perceive these positive aspects of the work environ-  Gender Differences in Satisfaction with the Type of Work University Employees Do: 412 Evidence from the University of Botswana ment did not differ significantly in the level of satisfac- tion with the type of work that th ey did. Men tended to be more satisfied than women with the type of work they did regardless of whether or not they felt misplaced at work (p=0.051 for those feeling mis- placed; p=0.271 for those who did not feel misplaced). Similarly, men tended to be more satisfied than women regardless of whether or not they felt that technology at work was adequate (p=0.150 for those who felt that technology was not adequate; p=0.091 for those who felt that technology was adequate). There were no significant differences in satisfaction between men and women who felt that teaching did not allow enough time for research (p=0.611) and between men and women who felt that teaching allowed enough time for research (p=0. 5 32 ). Table 4 shows that the association between gender and job satisfaction remained significant after controlling for negative work experiences and sources of stress. Males who often experienced stress from demands of work on private life were more highly satisfied than females who often experienced stress from demands of work on pri- vate life (p=0.006). Men were more satisfied with the type of work they did regardless of whether they experienced racism or tribalism (p=0.019 for those who often experienced racism or tribalism; p=0.022 for those who did not often ex- perienced racism or tribalism). Men also tended to be more satisfied than women with the type of work they did, whether or not they experienced xenophobia (ove rall p=0.002). Men and women who often had negative work ex- periences had a similar level of satisfaction with the type of work they did. Significant differences in satisfaction were found among employees who did not often have negative work experiences. For example, males who did not often experience gender discrimination were signifi- cantly more satisfied with the type o f work they did than females who did not experience gender discrimination (p=0.003). Other similarly significant gender differences in the level of job satisfaction were among those who did not experience: nepotism and favoritism (p=0.038); stress from the immediate supervisors (p=0.001); stress from domestic responsibilities (p=0.039); stress from relations with subordin ates (p=0.005) an d stress from the inappro- priateness of their qualification s (p=0.005 for moderately inappropriate qualifications; p=0.032 for very inappro- priate qualifications). 6.4 Estimating the Probability that an Employee would be Satisfied Given Gender The stepwise regression procedure was used to analyze the observed differences in satisfaction with the type of work that respondents did, when controlling for the po- tential confounders simultaneously. The variables that were removed by the stepwise regression procedure did not significantly add to our ability to predict satisfaction with the type of work respondents did (residual chi- square statistic 26.7; p=0.370).The goodness of fit of the proportional odds model was statistically significant (Wald Chi-square=41.5; df=11; p<0.001 and the Score Test statistic=10.5; d.f.=11; p=0.483). The estimates of the final prediction model are given in Table 5. The coefficient of gender in the proportional odds model was not significant, which suggests that, when modeling the effects of several variables simultaneously, there were no significant differences in satisfaction with the type of work that males and females did. The results show that employees in the old age category were almost 3 times more likely to be satisfied with the type of work they did than employees in the young age-group category (Odds Ratio=2.8). Employees who felt that teaching did not allow enough time for research were two-and-a-half times (Odds Ratio=2.6) more likely to be satisfied with the type of work they did than those who felt that teach- ing allows enough time for research). Employees who felt that the level of technology at work was up to the standard it should be, were more than twice as likely to be satisfied with the type of work they did than those who felt that the level of technology at work was below standard (Odds Ratio=2.4). Employees who felt that there was equity in the distribution of the work load in their departments were more than twice as likely to be satisfied with the type of work they did than those who felt that there was no equity in the distributio n of the workload in their departments (Odds Ratio=2.3, 95percent confidence interval=(1.26, 4.38). Employees who felt that they were underutilized were about 40% as likely to be satisfied with the type of work they did as those who felt that they were given enough to do at work (Odds Ratio=0.4, 95percent confidence interval=(0.20, 0.73). Given the above factors, other variables, including number of years in the organization, relations with sub- ordinates, feeling misplaced at work, etc., were found not to be important predictors of satisfaction with th e type of work that employees did. 7. Discussions This study sought to contribute to an understanding of gender differences in job satisfaction. It builds on studies that have found higher levels of job satisfaction among male employees [4,5,7,56], studies that have found hig her levels of job satisfaction among female employees [13,16,17], and studies that have found no difference in the levels of job satisfaction between male and female employees [18,19]. Copyright © 2009 SciRes JSSM  Gender Differences in Satisfaction with the Type of Work University Employees Do: Evidence from the University of Botswana Copyright © 2009 SciRes JSSM 413 Table 4. Association between gender and satisfaction with the type of work respondents did, controlling for negative work experiences & for sources of stress Level of Satisfaction High Moderate percent Among percent Among Association between gender and Satisfaction within each category Overall Association Controlling for factor Factor Controlled for Male Female Male Female Chi-sq p-value Chi-sq p-value Racism and Tribalism 9.2 0.002 Often 74.4 33.3 18.6 50.0 5.6 0.019 Not Often 79.3 66.7 16.5 25.9 5.3 0.022 Xenophobia 5.3 0.022 Often 83.8 50.0 10.8 40.0 3.4 0.066 Not Often 77.2 67.3 18.1 25.0 3.2 0.074 Gender Discrimination 8.8 0.003 Often 83.3 81.3 16.7 6.3 0.2 0.629 Not Often 78.1 60.6 17.0 31.7 8.7 0.003 Nepotism and Favoritism 6.1 0.014 Often 63.2 48.5 29.0 36.4 1.8 0.183 Not Often 81.0 68.6 15.3 25.6 4.3 0.038 Immediate Supervisor 4.3 0.038 Often 50.0 65.2 22.7 21.7 1.5 0.221 Not Often 81.0 63.8 16.7 29.8 10.5 0.001 Domestic Responsibilities 6.4 0.011 Often 73.0 50.0 17.2 36.7 2.2 0.141 Not Often 79.2 68.6 17.7 24.4 4.2 0.039 Demands of Work on Private Life 6.7 0.010 Often 97.1 44.1 14.0 41.2 7.5 0.006 Not Often 78.0 71.4 18.3 22.6 1.5 0.221 Relations with Subordinates 9.9 0.002 Often 70.0 42.9 20.0 42.9 2.1 0.144 Not Often 80.4 65.4 15.9 26.9 7.7 0.005 Appropriateness of Qualifications 4.5 0.034 High 79.9 82.5 15.9 14.3 0.2 0.619 Medium 72.7 44.7 25.5 47.4 7.8 0.005 Low 88.9 33.3 0.0 38.9 4.6 0.032 Medium 77.8 82.1 18.2 15.4 0.4 0.551 High 90.3 53.3 4.8 33.3 8.0 0.005  Gender Differences in Satisfaction with the Type of Work University Employees Do: 414 Evidence from the University of Botswana Table 5. Maximum likelihood estimates of the logistic model for satisfaction with the type of work employees do Parameter Estimate Standard Error Wald Chi-Square* P-value Odds Ratio 95percent CI for odds Ratio Intercept 1 -0.102 0.52 3 0.04 0.846 Intercept 2 1.892 0.562 11329.00 0.0 01 Gender -0.041 0.340 0.02 0.903 1.0 0.5 1.9 Age Middle age 0.580 0.351 2.74 0.098 1.8 0.9 3.5 Old age 1.025 0.489 4.39 0.036 2.8 1.1 7.3 Length of Service Worked for 4 to 9 year s at UB -0.603 0.363 2.75 0.097 0.5 0.3 1.1 Worked at least 10 years at UB-0.562 0.455 1.53 0.217 0.6 0.2 1.4 Stress from Relations with subordinates 0.524 0.551 0.90 0.342 1.7 0.6 5.0 Feeling technology is up to standard 0.886 0.314 7.95 0.005 2.4 1.3 4.5 Feeling under utilized -0.969 0.337 8.28 0.004 0.4 0.2 0.7 Feeling misplaced in depart- ment -0.544 0.425 1.63 0.201 0.6 0.3 1.3 Feeling equity in distribution of workload 0.854 0.317 7.24 0.007 2.3 1.3 4.4 Teaching does not allow time for research 0.938 0.339 7.63 0.006 2.6 1.3 5.0 The study investigated the level of satisfaction with the type of work that male and female employees of a univer- sity did; and sought to explain any differences found. Analyses began by exploring the bivariate association between gender and satisfaction with the type of work respondents did, and was improved by adopting condi- tional and multivariate analyses that shed more light on the initial association. The study has shown that altho ugh the majority of university employees in the sample were highly satisfied with the type of work that they did, males were significantly more satisfied than females. The study has also shown that male and female em- ployees differ in terms of many factors that affect em- ployee satisfaction such as age, marital statu s, citizenship, years of service at the institution, and so on. In order to gain more understanding of the relationship between gender and job satisfaction, it was importan t to determine and then control for these factors in the analyses. This ap- proach provided greater insight into the differences b etwe en males and females with certain background characteris- tics. For example, middle-aged males were more satisfied with the type of work they did than middle-aged females. Married males were more satisfied with their jobs than married f emales. But there w ere no differen ces in job satis- faction between single males and single females. Males who had 3 or more dependent children were more likely to be satisfied than women who had 3 or more dependent children. Males with a high salary were more satisfied w it h the type of work they did th an females with a h igh salary. Males who had worked for 10 or more years at the university were more satisfied with their jobs than women who had worked for the same number of years. This is consistent with findings that workers with less than ten years of work experience have less job satisfaction than those with ten or more years [38]. It is also consistent with studies that have found that job satisfaction in- creases progressively with length of service [16,57]. Controlling for work environment variables, negative experiences at work and for sources of stress enabled for a deeper understanding of how a positive or negative work environment and work experiences could affect male and female employees differently. It was observed that fe- male employees tended to be less satisfied than males regardless of whether or not they: experienced racism, tribalism or xenophobia; felt misplaced at work; or felt that technology at work was inadequate. It was also ob- served that females who experienced certain positive as- pects of the work environment were significantly less Copyright © 2009 SciRes JSSM  Gender Differences in Satisfaction with the Type of Work University Employees Do: 415 Evidence from the University of Botswana satisfied with their jobs than their male counterparts. These positive experiences included: autonomy at work; making a valued contribution; adequate level of supervi- sion; lack of tribalism in recruitment and promotion; and having clearly spelt ou t job descriptions and respons ibili- ties. Men and women who perceived or experienced these positive aspects of the work environment had a similar level of satisfaction wit h the type of work t hey di d. The study identified certain negative work-related ex- periences that affected job satisfaction. These negative ex- periences included: gender discrimination; nepotism and favoritism; stress from the immediate supervisor; stress from domestic responsibilities; stress from relations with subordinates; and stress from the inappropriateness of o n e’ s qualifications. Men and women who often had any of these negative experiences had a similar level of satisfac- tion with the type of wo rk they did. Thus positive asp ects of the work environment as well as negative (stressful) experiences had similar effects on male and female satis- faction with the type of work they did. Only one negative work experience was associated with females being less satisfied with their jobs than males. Females who often experienced stress from demands of work on private life were less satisfied than their male counterparts. Multivariate analyses, using the likelihood ratio criteria, showed that age-group was the most important predictor of satisfaction with the type of work that respondents did. This i s consisten t with sev eral stud ies that fo u nd t ha t o ld er workers were more satisfied with their jobs than younger workers [7,57,58]. Other important factors in the multi- variate model involved aspects of the work itself. Re- spondents who felt that teaching did not allow enough time for research were significantly more likely to be satisfied with the type of work they did than those who did not perceive conflict between teaching and research responsibilities. Perhaps those who were actively in- volved in both teaching and research experienced the competition for time, energy and effort between the two activities of a practicing academic. Such employees would have had an understanding of the importance of research and teaching in the university value and reward systems and may have been rewarded for successfully juggling the two very important aspects of academic life, which is a prerequisite for liking an academic job. The model further shows that employees who took ad- vantage of technological advancement derived higher satisfaction with the type of work they did. Similarly, employees who experienced equity in the distribution of the workload in their departments were generally more satisfied with their jobs. Those who did not have much to do at work (i.e. those who felt under-utilized) derived less satisfaction with the type of work they did than those who had adeq uate work to do, regardless of whether th ey were male or female. 8. Conclusions Job satisfaction is an important factor for any organiza- tion to achieve among its employees. It should help to maintain stability and productivity in the operations of academic institutions and of other organizations. Dissat- isfaction with work has been linked to absenteeism, poor performance and staff turnover at United Kingdom uni- versities [59]. It may lead to stress and ultimately to burnout if allowed to continue unabated [60]. It is, therefore, im- portant for university managers and policy makers to identify factors that they can address in order to improve levels of job satisfaction among their workers. This study addressed the question whether gender can help predict or determine employee satisfaction with the type of work they do. Bivariate analysis suggest that gender is an important factor that affects levels of job satisfaction, and should therefore be taken seriously by managers. Conditional analysis based on adding one control variable at a time shed further light on the relationship between gender and job satisfaction by specifying the conditions under which men and women have different levels of satisfaction. Multivariate analysis showed that gender ranked lower than many other factors in explain- ing the level of satisfaction with the type of work that university employees did, and the final model did not include gender as a predictive variable. The most parsimonious model of satisfaction with the type of work that university employees did included the following five predictive attributes: 1) be longing to an ol de r age group; 2) understanding the competing demands of teaching and research responsibilities; 3) taking advan- tage of technological advancement at work; 4) perceiving equity in the distribution of the workload; 5) feeling that one has enough to do at work. Once the above five fac- tors are given, gender and other variables, including indi- vidual background characteristics, measures of personal health and well-being, attributes of the home environment, a t t ri bu t es of the work environment, characteristics of the job itself, and level of job commitment that have been found to be associated with job satisfaction in this and other studies, were no longer important predictors of satisfaction with the type of work that employees do in a university. The study has made a contribution to research method- ology by illustrating that conclusions based on bivariate analyses alone have some limitations. Thus while man- agers should con tinue to be sensitive to the importance of gender differences in the workplace, they should be aware that other factors, which they can control or have influence over, determine whether or not employees are satisfied with the type of work that they do, and need to be addressed. Policies aimed at improving job satisfaction should, among other things, ensure that the distribution of the workload is transparent and equitable. Supervisors should regularly evaluate the workload of those who Copyright © 2009 SciRes JSSM  Gender Differences in Satisfaction with the Type of Work University Employees Do: 416 Evidence from the University of Botswana work under their leadership and ensure that they are not under-utilized or overworked. This study has several limitations. First, since the study used a cross-section and correlation design that identified significant associations, it cannot be used to make causal inferences among variables. Future studies should adopt longitudinal designs that that would enable cause and e ff e ct inferences to be drawn. Second, the study relied on self- reporting and not observations of behavior or in-depth in- terviews. This reduces the ability to interpret observed associations between variables and improve understanding of the findings. While the findings are interesting, gener- alizations to university employees and to other professional groups must be investigated further or made with caveats. REFERENCES [1] J. C. Kwesiga and E. N. Ssendi wal a, “Ge nde r ma inst reami ng in the university context : Prospects and challenges at Maker- ere University, Uganda,” Women’s Studies International Fo- rum, Vol. 29, No. 6, p p. 592–60 5, 2006 . [2] Mookodi and D. Fuh, “Finding the missing male in gen- der discourses in Botswana,” Pula: Botswana Journal of African Studies, Vol. 18, No. 1, pp. 31–42, 2004. [3] E. M. Alexander, “Beyond inequalities 2005: Women in Botswana,” Southern African Research and Documenta- tion Centre, Women in Development Southern Africa Awareness Program; Women's NGO Coalition (Bot- swana). Botswana WNGOC/SARDC, 2005. [4] J. Lacy and B. A. Sheehan, “Job satisfaction among aca- demic staff: An international perspective,” Higher Educa- tion, Vol. 34, No. 3, pp. 305–322, 1997. [5] L. Cooper and M. Kelly, “Occupational stress in head- teachers: A national UK study,” British Journal of Educa- tional Psychology, Vol. 63, No. 1, pp. 130–143, 1993. [6] J. K. Maphorisa, “Job satisfaction of Batswana secondary school teachers,” Unpublished M Ed Thesis, University of Botswana, 1997. [7] O. Siu, “Predictors of job satisfaction and absenteeism in two samples of Hong Kong nurses,” Journal of Advanced Nursing, Vol. 40, No. 2, pp. 218–229, 2002. [8] D. Bendall-Lyon and T. L. Powers, “The impact of gender differences on change in satisfaction over time,” Journal of Consumer Mark eting, Vol. 19, No . 1, p p. 12–23 , 2002. [9] H. Amaro, N. F. Russo, and J. Johnson, “Family and work predictors of psychological well-being among Hispanic women professionals,” Psychology of Women Quarterly, Vol. 11, No. 4, pp. 505–521, 1987. [10] U. Sekaran, “Understanding the dynamics of self-concept of members in dual-career families,” Human Relations, Vol. 42, No. 2, pp. 97–116, 1989. [11] S. L. Hanson, G. T. Cornwell, G. F. DeJong, and C. S. Stokes, “Consequences of involuntary low parity for women’s perception of homemaker and work roles: Find- ings from a 24-year longitudinal study,” Sociology and Social Research, Vol. 68, No. 3, pp. 326–349, 1984. [12] V. Baxter, “The differential effects of technology, individ- ual attributes, and perceived job rewards on job satisfac- tion,” Sociological Spectrum, Vol. 10, pp. 249–269, 1990. [13] T. Oshagbemi and C. Hickson, “Some aspects of overall job satisfaction: A binomial logit model,” Journal of Managerial Psychology, Vol. 18, No. 4, pp. 357–367, 2003. [14] E. Terpstra and A. L. Honoree, “Job satisfaction and pay satisfaction levels of university faculty by discipline type and geographical region,” Education, Vol. 124, No. 3, pp. 528–539, 2004. [15] Thilmany, “Formula for job satisfaction,” American Soci- ety of Mechanical Engineering-CIME, Michigan, 2004. [16] K. V. Rondeau and L. H. Francescutti, “Emergency de- partment overcrowding: The impact of resource scarcity on physician job satisfaction,” Journal of Healthcare Management, Vol. 50, No. 5, pp. 327–340, 2005. [17] S. V. Gardner, M. F. M. Jame s, and N. R. Evans, “Ge nder issues among South African anesthetists,” South African Medical Journal, Vol. 92, No. 9, pp. 732–736, 2002. [18] J. K. Eskildsen, K. Kristensen, and A. H. Westlund, “Work motivation and job satisfaction in the Nordic countrie s,” Em- ployee Relations, Vol. 26, No. 2 , pp. 122–136 , 2004. [19] A. Schneer and F. Reitman, “The impact of gender as managerial careers unfold,” Journal of Vocational Behav- ior, Vol. 47, No. 3, pp. 290–315, 1995. [20] J. Cranny, P. C. Smith, and E. F. Stone, “Job satisfaction: How people feel about their jobs and how it affects their performance,” New York. Lexington books, 1992. [21] T. T. Fako and N. Forcheh, “Job satisfaction among nurses in Botswana,” Journal of the Sociological Associa- tion of South Africa, Vol. 31, No. 1, pp. 10–21, 2000. [22] R. W. Rowden and C. T. Conine, “The impact of work- place learning on job satisfaction in small US commercial banks,” Journal of Workplace Learning, Vol. 17, No. 4, pp. 215–230, 2005. [23] S. M. Donohue and J. S. Heywood, “Job Satisfaction and gender: An expanded specification from the NLSY,” In- ternational Journal of Manpower, Vol. 25, No. 2, pp. 211–238, 2004. [24] A. Freund, “Commitment and job satisfaction as predictors of turnover intentions among welfare workers,” Admini- stration in Social Work, Vol. 29, No. 2, pp. 5–21, 2005. [25] L. Evans, “Understanding teacher morale and job satisfac- tion,” Teaching and Teacher Education, Vol. 13, No. 8, pp. 831–845, 1997. [26] W. Moyl e, W. Skinner, W. Rowe, and C. Gork, “Views of Job satisfaction and dissatisfaction in Australian long-term care,” Journal of Clinical Nursing, Vol. 12, No. 2, pp. 168–176, 2003. [27] J. Garcia-Bernal, A. Gargallo-Castel, M. Marzo-Navarro, and P. Rivera-Torres, “Job satisfaction: Empirical evi- dence of gender differences,” Women in Management Review, Vol. 20, No. 4, pp. 279–288, 2005. [28] A. D. Koustelios, “Personal characteristics and job satis faction of Greek teachers,” International Journal of Edu- Copyright © 2009 SciRes JSSM  Gender Differences in Satisfaction with the Type of Work University Employees Do: Evidence from the University of Botswana Copyright © 2009 SciRes JSSM 417 cational Management, Vol. 15, No. 7, pp. 354–358, 2001. [29] Petty, E. W. Brewer, and B. Brown, “Job satisfaction among employees of a youth development organization,” Journal of Child and Youth Care Forum, Vol. 34, No. 1, pp. 57–73, 2005. [30] M. M. Gruneberg, “Understanding job satisfaction,” Mac- millan Press, London, 1979. [31] R. (Jr.) Schermerhorn, J. G. Hunt, and R. N. Osborn, “Ba- sic organizational behavior,” John Wiley & Sons, New York, 1995. [32] V. M. Dendinger, G. A. Adams, and J. D. Jacobson, “Rea- sons for working and their relationship to retirement atti- tudes, job satisfaction and occupational self-efficacy of bridge employees,” International Journal of Aging and Human Development, Vol. 61, No. 1, pp. 21–35, 2005. [33] A. Aksu and A. Aktas, “Job satisfaction of managers in tourism: Cases in the Antalya region of Turkey,” Mana- gerial Auditing Journal, Vol. 20, No. 5, pp. 479–488, 2005. [34] L. A. Flowers, “Job satisfaction differentials among Afri- can American faculty at 2-year and 4-year institutions,” Community College Journal of Research and Practice, Vol. 29, No. 4, 317–328, 2005. [35] S. Tyson and T. Jackson, “The essence of organizational behavior,” Prentice Hall, New York, 1992. [36] Pollard, “Job satisfaction among newsworkers: The influ- ence of professionalism, perceptions of organizational struc- ture, and social attributes,” Journalism and Mass Commu- nications Quarterly, Vol. 72, No. 3, pp. 682–697, 1995. [37] T. Oshagbemi, “The influence of rank on the job satisfac- tion of organizational members,” Journal of Managerial Psychology, Vol. 12, No. 8, pp. 511–519, 1997. [38] C. M. Hellman, “Job satisfaction and intent to leave,” The Journal of Social Psychology, Vol. 137, No. 6, pp. 677–689, 1997. [39] D. Lund, “Organizational culture and job satisfaction,” Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, Vol. 18, No. 3, pp. 219–236, 2003. [40] L. Levy-Garboua and C. Montmarquette, “Reported job satisfaction, what does it mean,” Journal of Socio- Economics, Vol. 33, No. 2, pp. 135–151, 2004. [41] K. Hyrkas, “Clinical supervision, burnout, and job satis- faction among mental health and psychiatric nurses in Finland,” Issues in Mental Health Nursing, Vol. 26, No. 5, pp. 531–556, 2005. [42] N. O. Pors and C. G. Johannsen, “Job satisfaction and motivational strategies among library directors,” New Li- brary World, Vol. 103, No. 1177, pp. 199–208, 2002. [43] R. J. Burke, “Organizational values, work experiences and satisfactions among managerial and professional women,” Journal of Management Development, Vol. 20, No. 4, pp. 346–354, 2001. [44] P. E. Spector, “Job satisfaction: application, assessment, causes and consequences,” Sage Publications, CA, 1997. [45] H. C. Koh and E. H. Y. Boo, “Organizational ethics and employee satisfaction and commitment, ” Management Decision, Vol. 42, No. 5, pp. 677–693, 2004. [46] R. W. Gimbel, S. Lehrman, M. A. Strosberg, V. Ziac, J. Freedman, K. Savicki, and L. Tackley, “Organizational and environmental predictors of job satisfaction in com- munity based HIV-AIDS services organizations,” Social Work Research, Vol. 26, No. 1, pp. 43–55, 2002. [47] S. A. Sparks, K. J. Corcoran, L. A. Nabors, and C. A. Hovanitz, “Job satisfaction and subjective well being in a sample of nurses,” Journal of Applied Social Psychology, Vol. 35, No. 5, pp. 922–938, 2005. [48] L. B. Rosenfed, J. M. Richman, and S. K. May, “Information adequacy, job satisfaction and organizational culture in a dispersed-network organization,” Journal of Applied Com- munication Research, Vo l. 32, N o. 1, pp . 28–54 , 2004. [49] M. E. Capella and J. D. Andrew, “The relationship be- tween counselor job satisfaction and consumer satisfac- tion in vocational rehabilitation,” Rehabilitation Counsel- ing Bulletin, Vol. 47, No. 4, pp. 205–214, 2004. [50] Harrington, N. Bean, D. Pintello, and D. Mathews, “Job satisfaction and burnout: Predictors of intentions to leave a job in a military setting,” Administration in Social Work, Vol. 25, No. 3, pp. 1–16, 2001. [51] P. Krueger, K. Brazil, L. Lohfeld, H. G. Edward, D. Lewis, and D. E. Tjam, “Organisation specific predictors of job satisfaction: Findings from a Canadian multi-site quality of work life cross-sectional survey,” BMC Health Services Research, Vol. 2, No. 6, pp. 1–6, 2002. [52] Teferra and P. G. Altbach, (eds.), “African higher educa- tion: An international reference handbook,” Indiana Uni- versity Press, Bloomington, 2003. [53] J. L. Fleiss, “Statistical methods for rates and propor- tions,” John Wiley and Sons, New York, 1981. [54] P. McCullagh and J. A. Nelder, “Generalized linear mod- els,” Second Edition, Chapman & Hall, London, 1989. [55] W. N. Venables and B. D. Ripley, “Modern applied statis- tics with S-Plus,” Springer, New York, 1999. [56] A. Crossman and B. Abou-Zaki, “Job satisfaction and em- ployee performance of Lebanese banking staff,” Journal of Managerial Psyc hology, Vol. 18 , No. 4 , pp. 368–376 , 2003 . [57] C-K. Cheung and S. A. Scherling, “Job satisfaction, work values and sex differences in Taiwan’s organization,” Journal of Psychology, Vol. 133, No. 5, pp. 563–575, 1999. [58] K. B. Ang, C. T. Goh, and H. C. Koh, “The impact of age on the job satisfaction of accountants,” Personnel Review, Vol. 22, No. 1, pp. 31–39, 1993. [59] T. Oshagbemi, “Personal correlates of job satisfaction: empirical evidence from UK universities,” International Journal of Social Economics, Vol. 30, No. 12, pp. 1210–1232, 2003. [60] L. C. Pearson and W. Moomaw, “The relationship be- tween teacher autonomy and stress, work satisfaction, empowerment and professionalism,” Educational Re- search Quarterly, Vol. 29, No. 1, pp. 38–54, 2005. |