Paper Menu >>

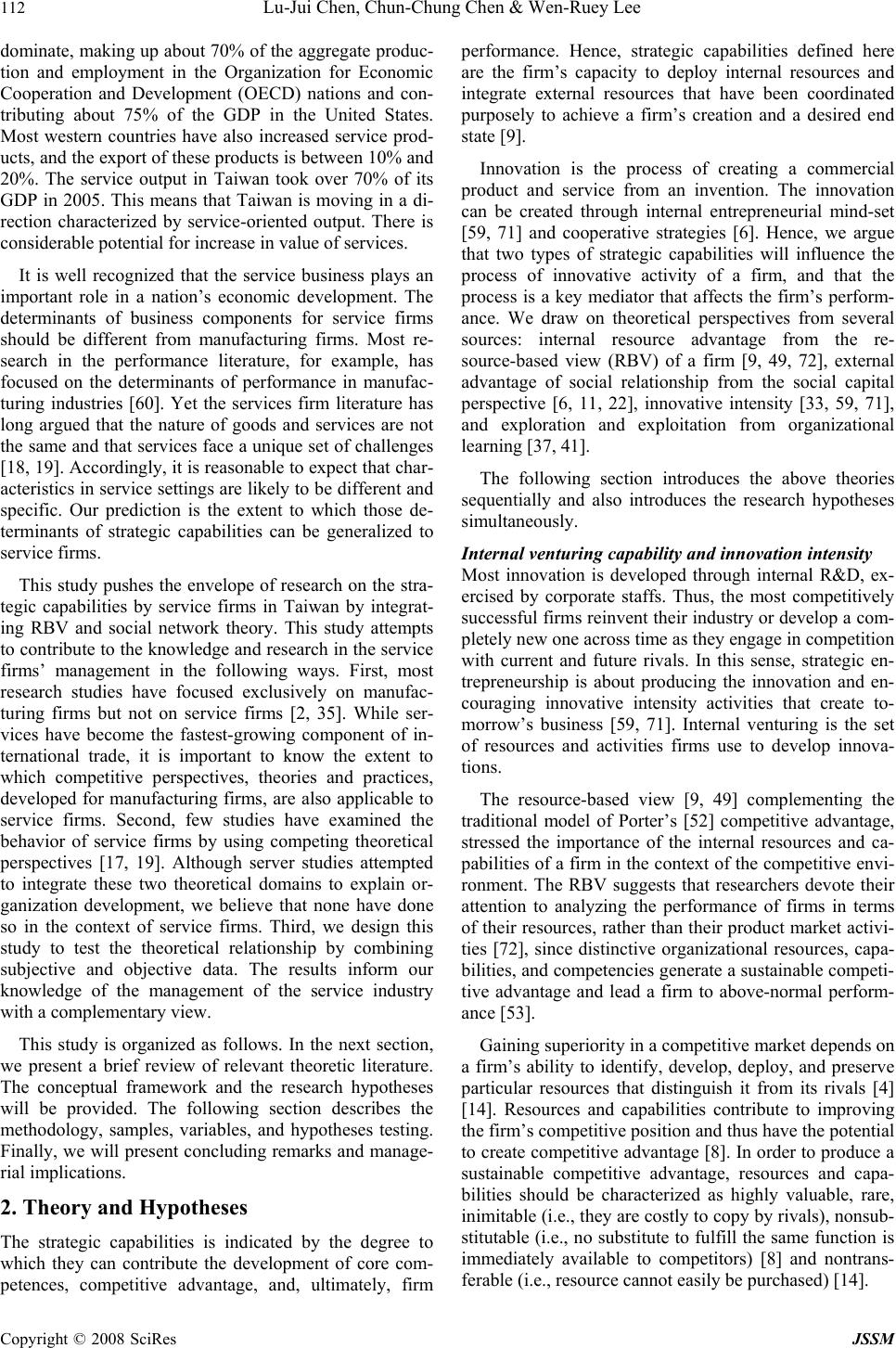

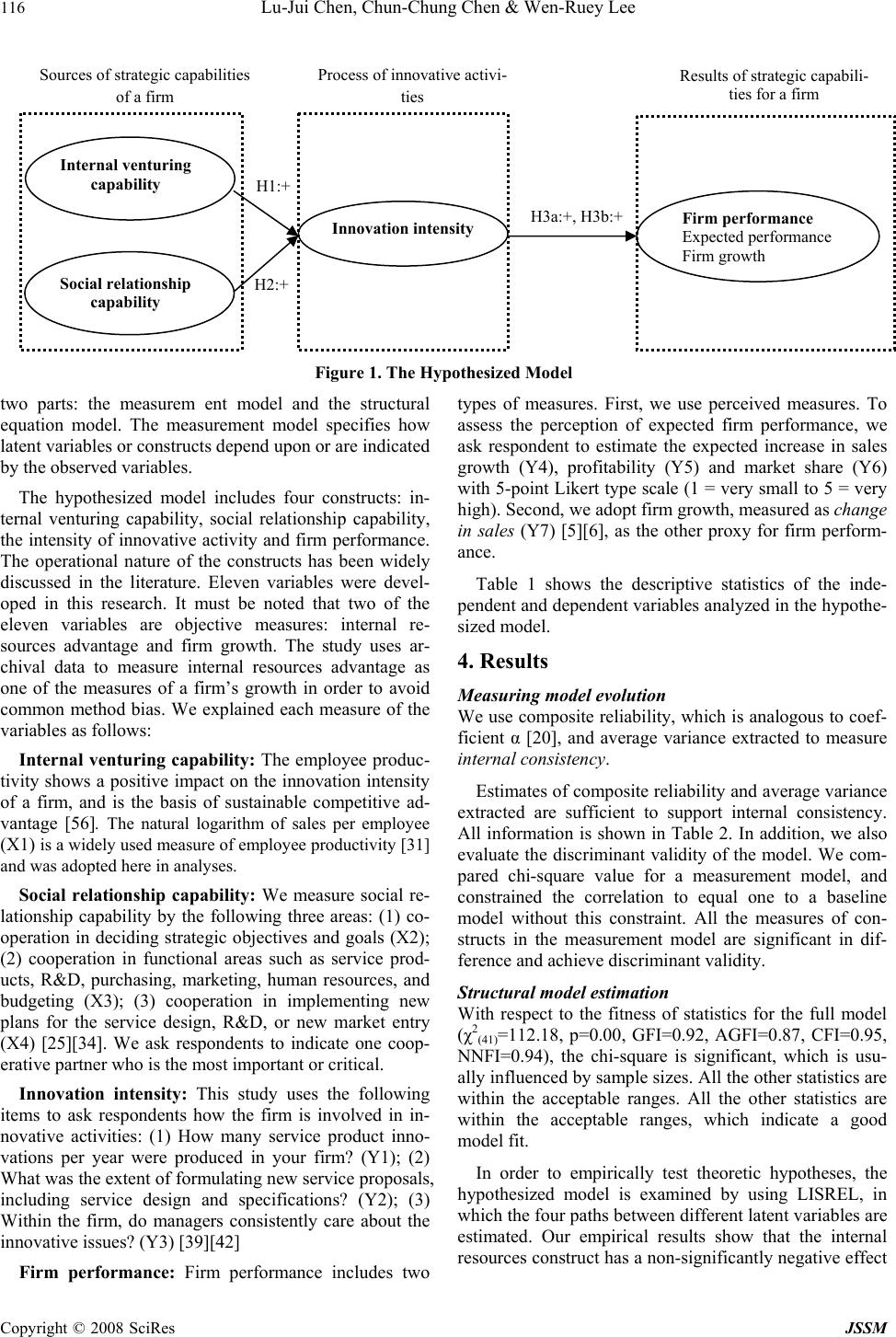

Journal Menu >>

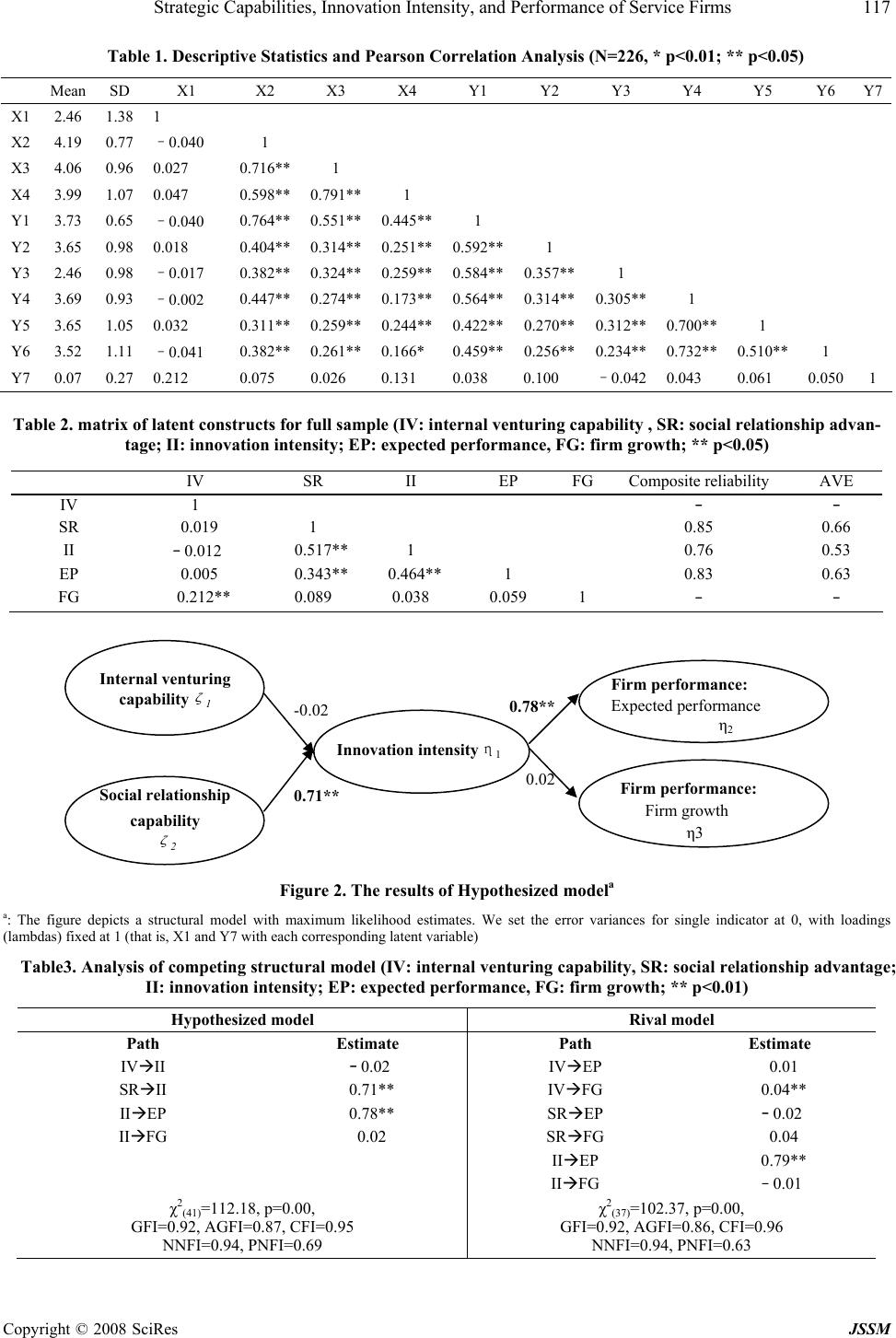

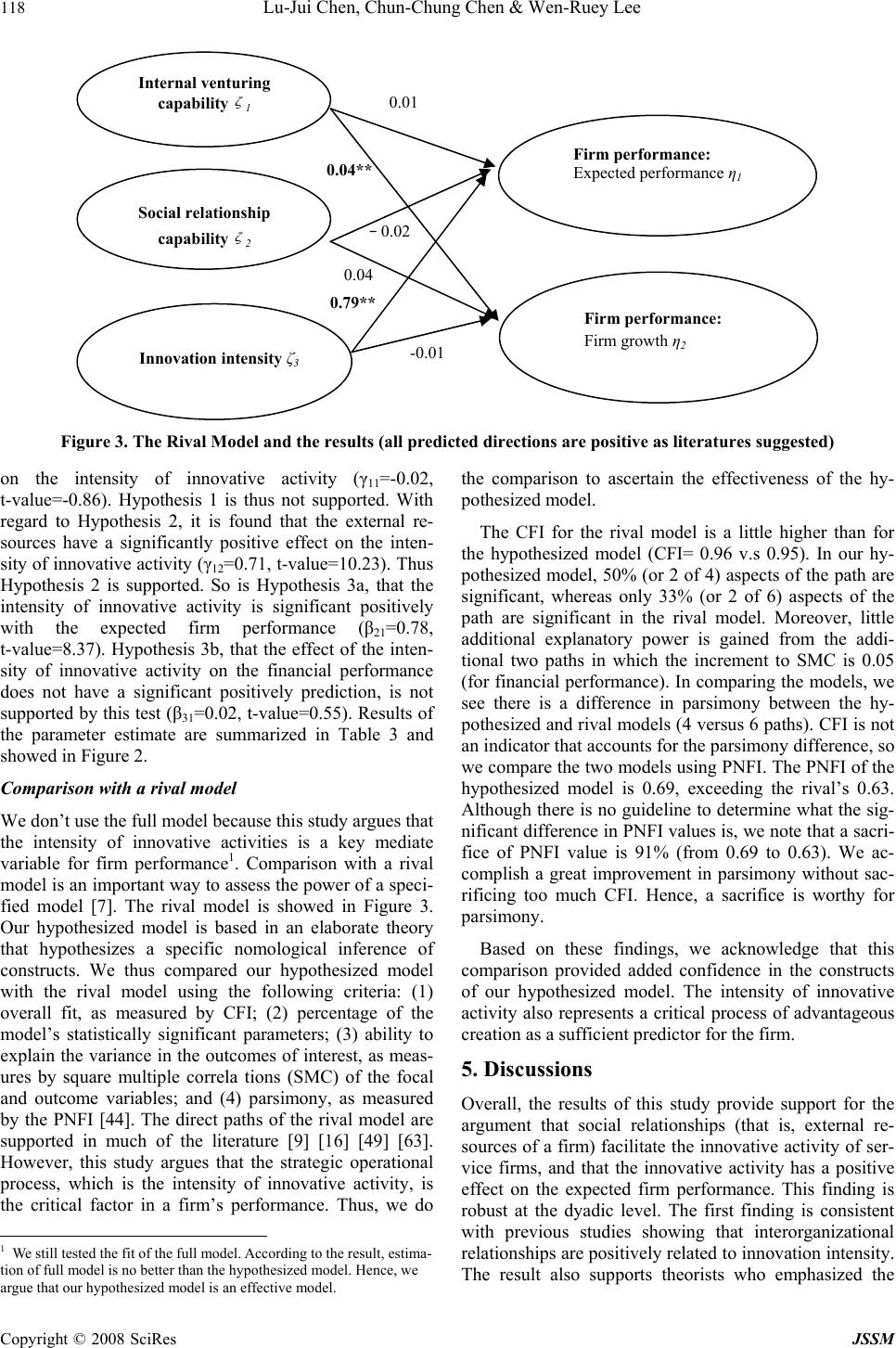

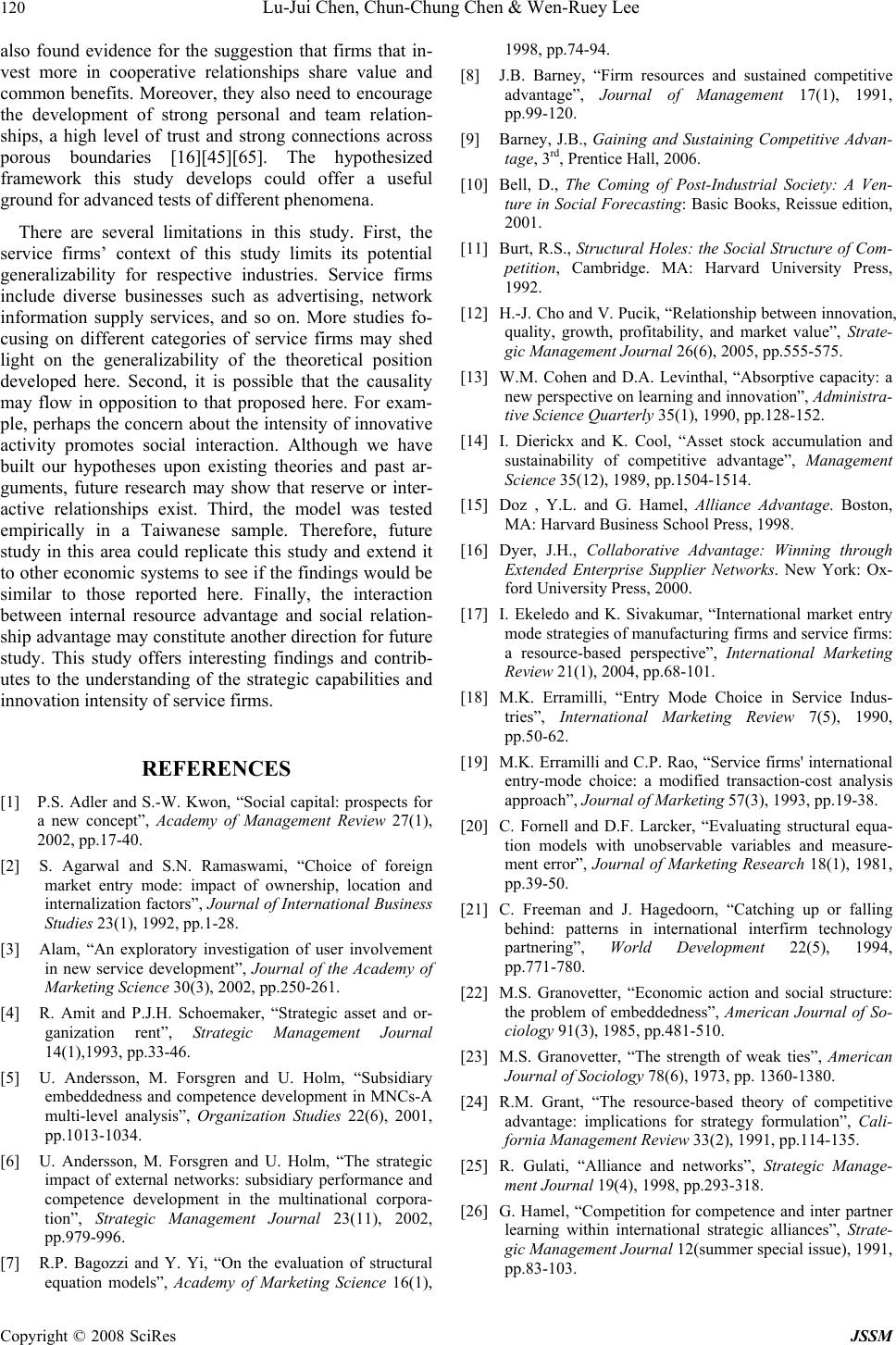

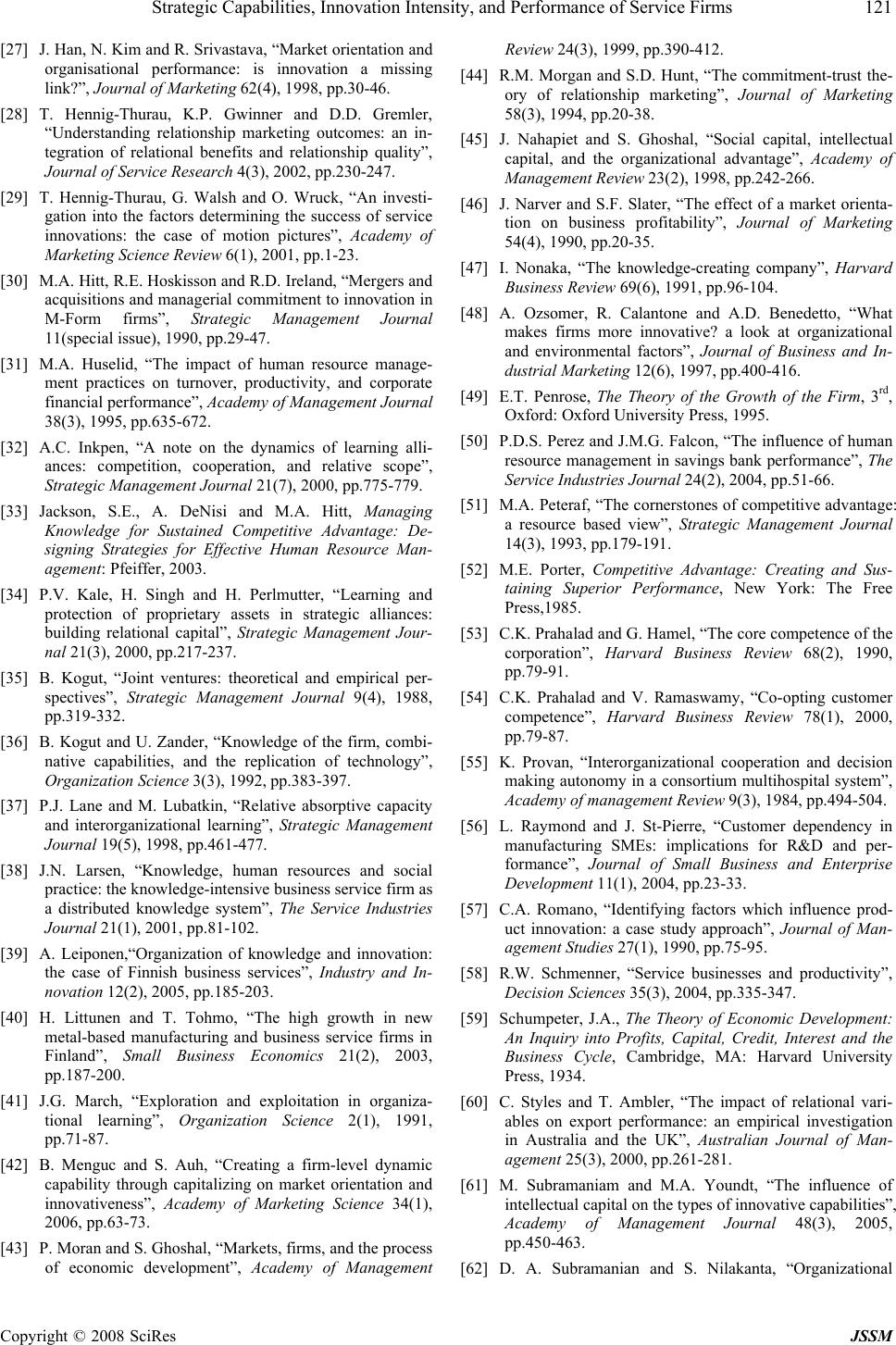

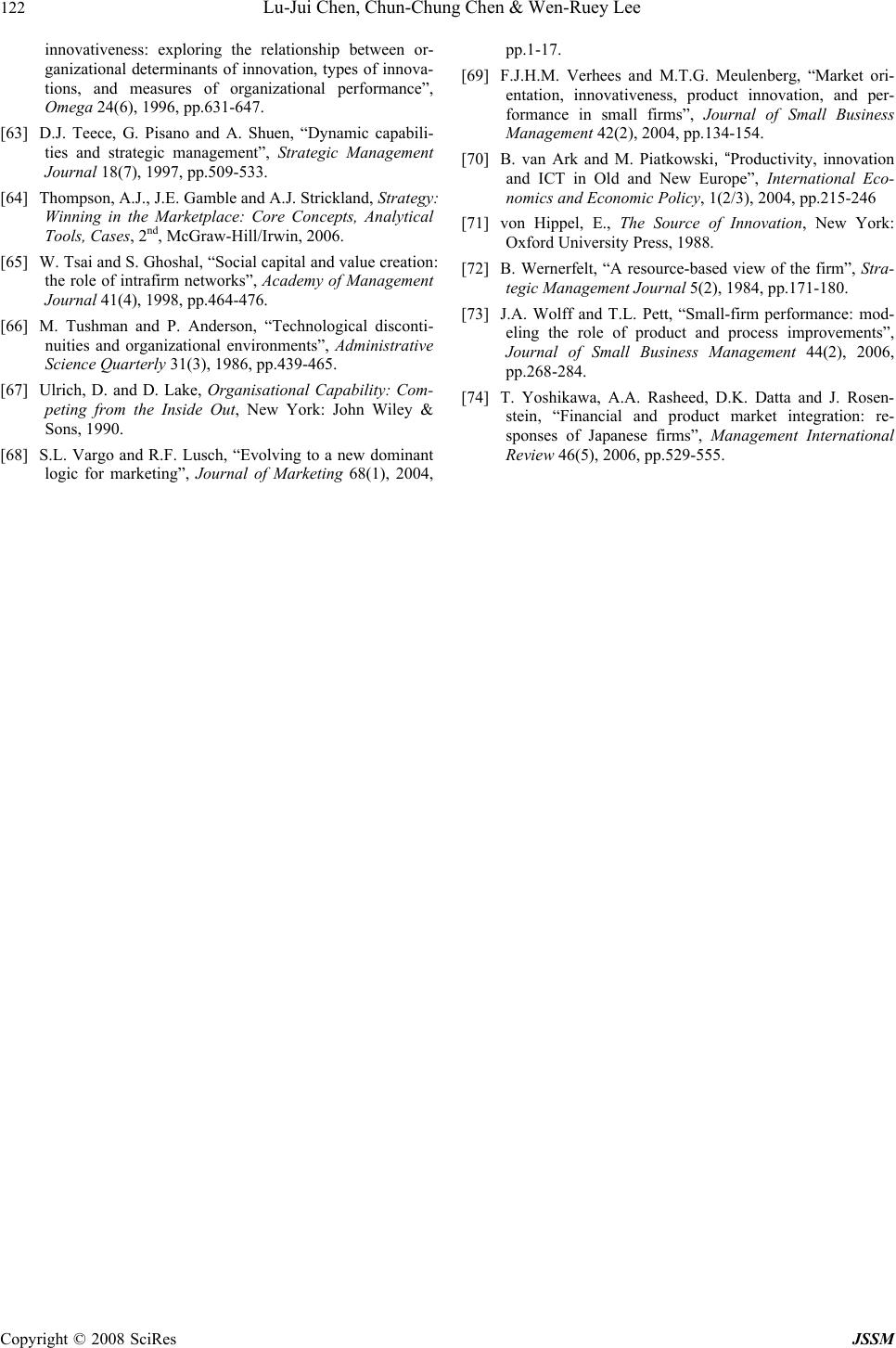

J. Serv. Sci. & Management, 2008, 1: 111-122 Published Online August 2008 in SciRes (www.SRPublishing.org/journal/jssm) Copyright © 2008 SciRes JSSM BBStrategic Capabilities, Innovation Intensity, and Performance of Service Firms Lu-Jui Chen1, Chun-Chung Chen2 & Wen-Ruey Lee3 M 1MingChuan University 2National Taiwan University 3National Taipei College of Business Email: shunyde@mcu.edu.tw, osimchen@ntu.edu.tw, wrlee@webmail.ntcb.edu.tw P ABSTRACT This study developed and empirically tested a model examining the relationships among strategic capabilities, innova- tion intensity, and firm performance. Strategic capabilities include internal venturing capability and social relationship capability. Analyzing a sample of service firms from Taiwan, the study indicates that social relationships with other firms are important to facilitate innovative activities of service firms. Innovation intensity further helps service firms to improve a firm’s expected performance. However, internal resources capability does not show the expected effect on innovation intensity. And innovation intensity is also not related to a firm’s growth. Keywords: resource-based view, social relationship, innovation intensity, firm performance, service firms 1. Introduction This study explores the relationships between strategic capabilities, firm’s innovation and the performance of the service firms. Innovations of firm create new jobs, gener- ate new wealth for firm. However, we do not know much about value of the extent to firm’s strategic capabilities on innovation, since previous studies have explored innova- tion without exposing its strategic capabilities. In this paper, we try to reveal the role of strategic capabili- ties—especially strategic in internal capabilities and in external networks—in the innovation creation process. And we also deal with the performance implication of strategy of with innovation. Two guiding theo- ries—resource-based view and social network—were invoked to account for the value of innovation and per- formance. Resource-based view (RBV) emphasizes firm with idiosyncratic resources [9] that are owned or controlled by the firm [49]. These capabilities of deploying re- sources made firms heterogeneous in nature. RBV regards the firm as a bundle of resources and suggests that their characteristics make a positive effect to the potential of innovation, and by implication of its performance. There are an increasing number of studies focusing on the com- petitive factors of firms. The studies show that intangible and tangible resources [24] and human resource man- agement [30], among others, are elements that clearly contribute to firm’s internal capabilities. Social networks advance that external connections are the sources of competitive advantages [6]. External net- works with suppliers, customers and others would facili- tate the product/service mobilized and concrete. Firm transacts with outside entities in order to acquire external resources and opportunities, adjusted for the firm’s poten- tial value. Social network theory implies that its relational characteristics are embedded with creative opportunities and potentials for the process of value in firm. Services have been increasingly providing intelligent inputs, adding products with a wide range of value and using other technological processes in this new economic time [68]. Firms create value by offering the types of ser- vices that customers need, at an acceptable price. In re- turn, firms receive value from their internal property and their stakeholders. Unlike manufacturing firms, which rely on patented technologies or unique products, service firms gain their competitive advantage primarily through their ability of combination to make use of their proprie- tary knowledge. The activity of service firms is an “inter- action between human and human” (or organization and organization). It is contrary to Daniel Bell’s characteriza- tion, which considers pre-industrial society as a “game against nature,” and industrial society as a “game against fabricated nature” [10]. Thus, the service industry needs not only technical skill, but also social skill. Services can be the initial element in producing an in- novative packaging material through R & D, or the “me- diating” element in developing a major mining project. In other instances, services firms add product value by pro- viding convenience, health and knowledge. For decades, services make up the bulk of nowadays’ economy and also account for most of the growth. In fact, services now  112 Lu-Jui Chen, Chun-Chung Chen & Wen-Ruey Lee Copyright © 2008 SciRes JSSM dominate, making up about 70% of the aggregate produc- tion and employment in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) nations and con- tributing about 75% of the GDP in the United States. Most western countries have also increased service prod- ucts, and the export of these products is between 10% and 20%. The service output in Taiwan took over 70% of its GDP in 2005. This means that Taiwan is moving in a di- rection characterized by service-oriented output. There is considerable potential for increase in value of services. It is well recognized that the service business plays an important role in a nation’s economic development. The determinants of business components for service firms should be different from manufacturing firms. Most re- search in the performance literature, for example, has focused on the determinants of performance in manufac- turing industries [60]. Yet the services firm literature has long argued that the nature of goods and services are not the same and that services face a unique set of challenges [18, 19]. Accordingly, it is reasonable to expect that char- acteristics in service settings are likely to be different and specific. Our prediction is the extent to which those de- terminants of strategic capabilities can be generalized to service firms. This study pushes the envelope of research on the stra- tegic capabilities by service firms in Taiwan by integrat- ing RBV and social network theory. This study attempts to contribute to the knowledge and research in the service firms’ management in the following ways. First, most research studies have focused exclusively on manufac- turing firms but not on service firms [2, 35]. While ser- vices have become the fastest-growing component of in- ternational trade, it is important to know the extent to which competitive perspectives, theories and practices, developed for manufacturing firms, are also applicable to service firms. Second, few studies have examined the behavior of service firms by using competing theoretical perspectives [17, 19]. Although server studies attempted to integrate these two theoretical domains to explain or- ganization development, we believe that none have done so in the context of service firms. Third, we design this study to test the theoretical relationship by combining subjective and objective data. The results inform our knowledge of the management of the service industry with a complementary view. This study is organized as follows. In the next section, we present a brief review of relevant theoretic literature. The conceptual framework and the research hypotheses will be provided. The following section describes the methodology, samples, variables, and hypotheses testing. Finally, we will present concluding remarks and manage- rial implications. 2. Theory and Hypotheses The strategic capabilities is indicated by the degree to which they can contribute the development of core com- petences, competitive advantage, and, ultimately, firm performance. Hence, strategic capabilities defined here are the firm’s capacity to deploy internal resources and integrate external resources that have been coordinated purposely to achieve a firm’s creation and a desired end state [9]. Innovation is the process of creating a commercial product and service from an invention. The innovation can be created through internal entrepreneurial mind-set [59, 71] and cooperative strategies [6]. Hence, we argue that two types of strategic capabilities will influence the process of innovative activity of a firm, and that the process is a key mediator that affects the firm’s perform- ance. We draw on theoretical perspectives from several sources: internal resource advantage from the re- source-based view (RBV) of a firm [9, 49, 72], external advantage of social relationship from the social capital perspective [6, 11, 22], innovative intensity [33, 59, 71], and exploration and exploitation from organizational learning [37, 41]. The following section introduces the above theories sequentially and also introduces the research hypotheses simultaneously. Internal venturing capability and inno vation intensity Most innovation is developed through internal R&D, ex- ercised by corporate staffs. Thus, the most competitively successful firms reinvent their industry or develop a com- pletely new one across time as they engage in competition with current and future rivals. In this sense, strategic en- trepreneurship is about producing the innovation and en- couraging innovative intensity activities that create to- morrow’s business [59, 71]. Internal venturing is the set of resources and activities firms use to develop innova- tions. The resource-based view [9, 49] complementing the traditional model of Porter’s [52] competitive advantage, stressed the importance of the internal resources and ca- pabilities of a firm in the context of the competitive envi- ronment. The RBV suggests that researchers devote their attention to analyzing the performance of firms in terms of their resources, rather than their product market activi- ties [72], since distinctive organizational resources, capa- bilities, and competencies generate a sustainable competi- tive advantage and lead a firm to above-normal perform- ance [53]. Gaining superiority in a competitive market depends on a firm’s ability to identify, develop, deploy, and preserve particular resources that distinguish it from its rivals [4] [14]. Resources and capabilities contribute to improving the firm’s competitive position and thus have the potential to create competitive advantage [8]. In order to produce a sustainable competitive advantage, resources and capa- bilities should be characterized as highly valuable, rare, inimitable (i.e., they are costly to copy by rivals), nonsub- stitutable (i.e., no substitute to fulfill the same function is immediately available to competitors) [8] and nontrans- ferable (i.e., resource cannot easily be purchased) [14].  BBStrategic Capabilities, Innovation Intensity, and Performance of Service Firms 113 Copyright © 2008 SciRes JSSM More recent studies emphasize the important of knowledge-based resources [36, 63], which is character- ized by firm employment [49]. Therefore, competitive advantage resides in the resources available to the firm [8, 63]. Recent extensions of RBV suggest that sustainable competitive advantages are not achieved through the stra- tegic utilization of any one kind of resource, but rather through the bundling and revitalizing of multiple, distinc- tive firm resources and competencies in order to create valued outputs capable of becoming sustainable competi- tive advantages [63]. The essence of human capital is the sheer intelligence of the organizational member [9]. According to RBV, firm employment enhances the potential of internal advantage, which is most difficult to imitate and can provide a firm with sustained competitive advantage [33]. The greater the employment potential, the more they can give a spe- cific advantage through cost savings from increased utili- zation, combination of resources, lower turnover and higher productivity from boosting the productivity of in- dividual workers. According to Jackson et al. [33] and Ulrich and Lake [67], employment can be further analyzed into the following three dimensions: capability and potential, motivation and commitment, and innovation and learning. Capability and potential includes concepts such as educational level, professional skills, experience, attitudes, personal networks, values, and the ability of current employees to evolve within the organization. Finally, innovation shows the degree to which employments are open to create. Innovation is increased by the quality of the human capital and an enhancement of the labor productivity [70]. Hence, this study proposes that ability of employment in the service firms can represent an internal resources advantage. For example, a service firm’s market orienta- tion and strategic decision-making are bundled together with internal complementary resources, such as innova- tion [42, 46]. And internal resources usually mean human resources, financial property, and management know-how, etc. However, the resource-based view of the firm [49, 72] stresses the resources that are bundled by the firm, which is understood as an organization characterized by admin- istrative routines. It is the services based on the firm's resources, rather than the resources per se, that constitute the firm's knowledge. Hence, the knowledge base of firms is intrinsically linked to the knowledge of their employees [38] and those that highlight the greater share of service activities and the tendency of high-skills services [50]. The production of services is almost entirely dependent on the ability of the firm to make use of the knowledge of the employees in the case of services. Innovative capabilities can be considered as a subset of dynamic organizational capabilities. The company sur- vived in difficult times and improved its market position- ing, establishing a reputation for innovation. Personnel competencies are improved in a number of ways (e.g. multi-skilled development) that are evident when a firm’s employees are engaged with customer or supplier peers. The sales per employee capture efficiency and effective- ness improvements for the firm [58, 74], which are often the central goal of restructuring a firm’s process and product. Organizational innovation is viewed as the functional systems and processes organizations utilize to upgrade a firm’s existing products, services, and processes, along with the creation and introduction of new products, ser- vices, and processes [66]. Innovation represents the commercialization of new technologies or technological change [71]. Hence this study infers innovation as “a complex activity which proceeds from the conceptualiza- tion of a new idea to a solution of the problem and then to the actual utilization of economic or social value.” As March [41] suggests, exploration and exploitation are essential for organization, but they compete for scarce resources. Thus, a firm’s capability to allocate scarce re- sources that can maximize the returns from either explo- ration or exploitation comprizes its intangible competen- cies. According to Penrose [49], Cohen and Levinthal [13], and Teece et al. [63], a firm innovates through learning processes that enable the firm to re-bundle and revitalize existing and newly acquired resources into core competencies and competitive advantages, and by apply- ing internally and externally created knowledge and technology to develop new products, services, and proc- esses. Most improvements to service activities are incre- mental. In effect, a firm’s innovative view may create a new market. For example, FedEx Corp. redefined the package delivery market. The internal resources of firms bring about competitive advantage, innovations and effi- ciency [40]. Because innovative activity is characterized by the continuous improvement of products and produc- tivity, the sudden and unpredictable changes in the threats and opportunities that a firm faces are called Schumpete- rian revolutions. Schumpeterian revolutions have the ef- fect of drastically changing the value of a firm’s resources by changing the threats and opportunities that face a firm. The RBV provides a unified approach in the conceptuali- zation of the foundation of innovation. Several research- ers have extended the RBV concepts linking to innovation [14, 51, 63]. We suggest that a firm’s level of overall in- novation is manifested in its capability to explore new possibilities. Likewise, a firm’s level of product or service quality is manifested in its capability to exploit currently established certainties. Hence, Hypothesis 1: A firm’s internal venturing capability has a positive relationship with the firm’s innovation intensity. Social relationship capab ility and innovation intensity Social capital could be understood roughly as the good- will that is engendered by the fabric of social relations and that can be mobilized to facilitate action [1]. The core of social capital is the idea that goodwill drawn from family, friends, workmates and acquaintances provides a  114 Lu-Jui Chen, Chun-Chung Chen & Wen-Ruey Lee Copyright © 2008 SciRes JSSM range of valuable resources, including information, influ- ence and solidarity [1, 23]. Recent research has applied social relationships as external advantage to a broader range of social phenomena, including relationships within and beyond the firm [11]. They control business benefits with outside entities [5, 6]. A firm’s network will consist of relationships as well as the firm’s position within the whole network of rela- tionships. There are two types of relationships for the business network. One is referred to the closeness of a firm’s set of direct and dyadic relationships, which has been labeled relational embeddedness. The other is the aspect of centrality of the firm in multiple-level relation- ships, which has been called structural embeddedness [22, 25]. For the clarity of analysis, the study focuses on dy- adic relationships. Firms create competitive advantage and economic value through effective interfirm collaboration [16]. So- cial relationships build on the general idea that economic actions are influenced by the social context in which they are embedded, and that actions can be influenced by oth- ers in social interaction [25]. Relational capital, which is so important at the dyadic level, rests upon close ties at the dyadic level and can also play an important role in creating business value and learning [34]. Tsai and Gho- shal [65] identify the social capital as the essential ante- cedent to facilitate the activity of value creation of firms. Absorptive capability is a critical feature that makes firms learn and assimilate outside knowledge [13]. Con- sidering collaboration as a learning opportunity [26], a firm may initiate collaboration relationships and create new know-how [32]. Lane and Lubatkin [37] have sug- gested that inter-organization relationships facilitate the difficulties of assimilation of knowledge. The breadth and the depth of the relationships between firms are associ- ated with mutual adaptation of activities and the trust ex- isting in the relationships. Mutual trust eliminates trans- action costs and also increases the opportunities to create new opportunities [16]. Firms are embedded in socio-economic networks rather than being isolated is- lands in the market [22] — no matter whether they are engaged in innovative activity or not. Thus collective learning, or cooperative learning, is the situation in which partners learn to work together [15], which often contrib- utes to the increase in the stock of knowledge. Innovation is equally important for large and small firms in the contemporary competitive and changing market. No firms—even the largest firms such as multi- nationals—can always undertake major innovations alone and overcome any resource barriers for innovative activi- ties. Hence, there is an increasing trend in strategic col- laborations [21, 25] and this trend is seen as an external advantage to the firm. Close contact and intense interac- tion between individual firms act as an effective mecha- nism to transfer or learn “sticky” and beneficial knowl- edge-how across the organizational interface. The com- bination of knowledge and the creation of innovation are complex social processes; much of the value of innova- tive concepts is fundamentally socially embedded [45]. Social relationships have become an important asset to multinational firms because of the need for appropriate resources (e.g., information, technology, knowledge, ac- cess to distribution networks, etc.) to compete effectively in the markets. For example, exchanges based on these linkages can facilitate product innovation, expedite re- source exchange and create intellectual capital [45, 65]. Service-centered logic implies that value is defined by and co-created with the consumer and determined by the customer on the basis of value-in-use, rather than being embedded in predefined output [68]. Thus, from a new service development perspective, the customers become not only a necessity, but also an opportunity. Service firms make their living by accessing, creating, and using information in ways that add value to an enter- prise and its stakeholders [28]. Thus, a firm that is located in a cooperative relationship of social interaction likely has greater potential to innovate and exchange know-how with other firms, because of its specific external advan- tages in the network. Firms gain advantages through close cooperation, and they obtain specific information about new products. Also, they can assess their value with re- spect to their needs, while producers gain insight into the user or customer needs and can adjust their innovation activity accordingly. Hence, Hypothesis 2: A firm’s social relationship capability has a positive relationship with the firm’s innovation inten- sity. Innovation intensity and firm performance The definition of firm performance, explored here, is based on the notion that a firm is an association of pro- ductive assets (including individuals) who voluntarily come together to obtain economic advantages [49] Own- ers of productive assets of a firm will make those assets available to a firm only if they are satisfied that the in- come they are receiving is at least as large as the income they could expect from any reasonable alternatives [9]. Depending on these insights, it is possible for us to out- line a firm’s performance by comparing the value that a firm creates using its productive assets with the value that managers of the firm expect to obtain. New sources of value are generated through novel de- ployments of resources [59]. New ways of exchanging and combining resources are important to create a firm’s value. A firm’s innovation is related with organizational learning [13, 65]. The more emphatically knowledge is learned and absorbed, the higher the performance a firm can achieve through the capability of innovation [37]. Innovation is considered vital for its contribution to business performance, and the literature consistently as- sociates it positively with performance. Empirically, this linkage for innovation and its impact on performance was  BBStrategic Capabilities, Innovation Intensity, and Performance of Service Firms 115 Copyright © 2008 SciRes JSSM validated by Han et al. [27]. Higher innovation possessed by a firm causes higher organizational performance in the market competition [62]. Considering the operational complexity of a service firm, the intensity of innovation is generally manifested in the form of product modification [69]. The firm requires diverse resources inputs and com- binative capabilities [36]. In the light of the growth of a firm, its ability of innovation will generate a competitive edge and business growth in the market [57]. Thus, a firm’s innovation has become important for it to increase growth of development and value creation [73]. According to Leiponen’s research about the Finnish Community Innovation Survey, more than 20% of service firms reported having launched new services in the pre- vious years [39]. In other words, recent survey data indi- cates that innovation does occur in the service industry. Because service firms face dynamic demand and market uncertainty, they are likely to pursue more proactive and more aggressive strategies, as uncertainty increases, through innovation activities [48]. The literature states a number of strongly allied concepts of innovation and ser- vice firms [3, 54, 71]. The new products or new processes introduced in help incumbent firms to safeguard their market position and sustain growth. In essence, the more dynamic or complex the environment, the greater the compulsion to innovate and the more innovative firms are likely to be. Customer tastes or expectations fluctuate; competitors, for example, introduce new products. The pressure on firms to innovate will be great and, hence, one may anticipate that the intensity of innovation is the decisive factor for service firms. This study intends to analyze the relationship between the intensity of organizational innovation and a firm’s performance. We opted to consider, first of all, the rela- tionship between organizational innovation and financial results, which have been the main focus of research on business strategy. Measure such as sales volumes, change in sales and market share expansion seem appropriate as measures of the firm’s performance. From a broader economic point of view, understanding innovation within service firms becomes vital as the share of the service sector in terms of GDP and employment keeps rising. But service activities’ value creation and outcomes have been slow or even negative [39]. The ef- fect of innovation does not always immediately affect economic and financial results. In other words, financial results are seen as a ‘lagging indicator’ for the measure of a firm [64]. Moreover, certain external factors may favor one firm over another, such as changes of government regulations or production or distribution costs [64]. For this reason, we also consider it appropriate to use per- ceived measures as considered in the literature. One way in which we posit performance is by examining the out- come of the firm’s innovation. Innovative outcomes will materialize over time rather than instantly, so the ex- pected performance—rather than the present perform- ance—should constitute another dependent variable. Fur- thermore, if goal attainment is at the heart of a firm’s performance, then we should also maintain that it is the market performance, rather than the present market per- formance, that should be assessed. Perceived measures are likely to reflect both enacted and potential outcome [55]. Therefore, we use expected performance as another measure of performance. Consequently, we use two per- formance indicators to predict a firm’s performance. Hence, Hypothesis 3a: A firm’s innovation intensity has a posi- tive relationship with its future performance. Hypothesis 3b: A firm’s innovation intensity has a posi- tive relationship with its growth. Hypotheses 1 to 3 are summarized in Figure 1. 3. Methods Sample and date collection This model is tested on samples of firms in the Taiwanese service industry. Data for this study come from two major sources. Data for social relationship capability, innovation intensity, and expected firm performance are perceptual measures; data for internal venturing capability and firm growth are from industrial secondary archives. A survey questionnaire was developed based on previous literature. We sent it to business managers familiar with the devel- opment of the service industry to verify questionnaire items and terms. Some minor changes in wording were made and the questionnaire was then adjusted. Our sample was drawn from the Top 5000-The Largest Corporations in Taiwan, 2006, compiled by China Credit of Information Service, Ltd (CCIS), Taiwan. This data source not only lists the sample companies that we need but also provides data about the firms. Because of missing data for some firms, this study collected data for 1,600 firms as a sample. These questionnaires were sent to sen- ior manager of these service firms. A t-test on the number of employees showed no significant differences in our sample and those that were not included in the sample. After several follow-ups, there were 237 responses. We exclude several incomplete questionnaires. There are 226 complete responses. The samples are comprised of 226 observations, meaning that we provide a valid sample size for the subsequent statistical analysis to be carried out. In order to ascertain that the response is effective, we sent another set of questionnaires to other managers in the responding firms. Nineteen of the second questionnaires were returned. We found a high degree of correlation between the two sets of responses. Hence, we argue that the first collection is sufficient for subsequent hypotheses testing. After the process of collecting questionnaires, we use archival data to provide information for the rest of the constructs as another source of analytic data. Variable measurement This study uses the LISREL (Linear Structural Relations) model as the analytical tool. Jöreskog introduced the LISREL model in 1973. The LISREL model consists of  116 Lu-Jui Chen, Chun-Chung Chen & Wen-Ruey Lee Copyright © 2008 SciRes JSSM Figure 1. The Hypothesized Model two parts: the measurem ent model and the structural equation model. The measurement model specifies how latent variables or constructs depend upon or are indicated by the observed variables. The hypothesized model includes four constructs: in- ternal venturing capability, social relationship capability, the intensity of innovative activity and firm performance. The operational nature of the constructs has been widely discussed in the literature. Eleven variables were devel- oped in this research. It must be noted that two of the eleven variables are objective measures: internal re- sources advantage and firm growth. The study uses ar- chival data to measure internal resources advantage as one of the measures of a firm’s growth in order to avoid common method bias. We explained each measure of the variables as follows: Internal venturing capability: The employee produc- tivity shows a positive impact on the innovation intensity of a firm, and is the basis of sustainable competitive ad- vantage [56]. The natural logarithm of sales per employee (X1) is a widely used measure of employee productivity [31] and was adopted here in analyses. Social relationship capability: We measure social re- lationship capability by the following three areas: (1) co- operation in deciding strategic objectives and goals (X2); (2) cooperation in functional areas such as service prod- ucts, R&D, purchasing, marketing, human resources, and budgeting (X3); (3) cooperation in implementing new plans for the service design, R&D, or new market entry (X4) [25][34]. We ask respondents to indicate one coop- erative partner who is the most important or critical. Innovation intensity: This study uses the following items to ask respondents how the firm is involved in in- novative activities: (1) How many service product inno- vations per year were produced in your firm? (Y1); (2) What was the extent of formulating new service proposals, including service design and specifications? (Y2); (3) Within the firm, do managers consistently care about the innovative issues? (Y3) [39][42] Firm performance: Firm performance includes two types of measures. First, we use perceived measures. To assess the perception of expected firm performance, we ask respondent to estimate the expected increase in sales growth (Y4), profitability (Y5) and market share (Y6) with 5-point Likert type scale (1 = very small to 5 = very high). Second, we adopt firm growth, measured as change in sales (Y7) [5][6], as the other proxy for firm perform- ance. Table 1 shows the descriptive statistics of the inde- pendent and dependent variables analyzed in the hypothe- sized model. 4. Results Measuring model evolution We use composite reliability, which is analogous to coef- ficient α [20], and average variance extracted to measure internal consistency. Estimates of composite reliability and average variance extracted are sufficient to support internal consistency. All information is shown in Table 2. In addition, we also evaluate the discriminant validity of the model. We com- pared chi-square value for a measurement model, and constrained the correlation to equal one to a baseline model without this constraint. All the measures of con- structs in the measurement model are significant in dif- ference and achieve discriminant validity. Structural model estimation With respect to the fitness of statistics for the full model (χ2 (41)=112.18, p=0.00, GFI=0.92, AGFI=0.87, CFI=0.95, NNFI=0.94), the chi-square is significant, which is usu- ally influenced by sample sizes. All the other statistics are within the acceptable ranges. All the other statistics are within the acceptable ranges, which indicate a good model fit. In order to empirically test theoretic hypotheses, the hypothesized model is examined by using LISREL, in which the four paths between different latent variables are estimated. Our empirical results show that the internal resources construct has a non-significantly negative effect H2:+ Social relationship capability Internal venturing capability Sources of strategic capabilities of a fir m H3a:+, H3b:+Firm performance Expected performance Firm growth Innovation intensity H1:+ Process of innovative activi- ties Results of strategic capabili- ties for a firm  BBStrategic Capabilities, Innovation Intensity, and Performance of Service Firms 117 Copyright © 2008 SciRes JSSM Table 1. Descriptive Statistics and Pearson Correlation Analysis (N=226, * p<0.01; ** p<0.05) Mean SD X1 X2 X3 X4 Y1 Y2 Y3 Y4 Y5 Y6 Y7 X1 2.46 1.38 1 X2 4.19 0.77 –0.040 1 X3 4.06 0.96 0.027 0.716** 1 X4 3.99 1.07 0.047 0.598** 0.791**1 Y1 3.73 0.65 –0.040 0.764** 0.551**0.445**1 Y2 3.65 0.98 0.018 0.404** 0.314** 0.251** 0.592**1 Y3 2.46 0.98 –0.017 0.382** 0.324** 0.259** 0.584**0.357**1 Y4 3.69 0.93 –0.002 0.447** 0.274** 0.173** 0.564**0.314**0.305**1 Y5 3.65 1.05 0.032 0.311** 0.259** 0.244**0.422**0.270**0.312**0.700** 1 Y6 3.52 1.11 –0.041 0.382** 0.261** 0.166* 0.459**0.256**0.234** 0.732** 0.510** 1 Y7 0.07 0.27 0.212 0.075 0.026 0.131 0.038 0.100 –0.042 0.043 0.061 0.0501 Table 2. matrix of latent constructs for full sample (IV: internal venturing capability , SR: social relationship advan- tage; II: innovation intensity; EP: expected performance, FG: firm growth; ** p<0.05) Figure 2. The results of Hypothesized modela a: The figure depicts a structural model with maximum likelihood estimates. We set the error variances for single indicator at 0, with loadings (lambdas) fixed at 1 (that is, X1 and Y7 with each corresponding latent variable) Table3. Analysis of competing structural model (IV: internal venturing capability, SR: social relationship advantage ; II: innovation intensity; EP: expected performance, FG: firm growth; ** p<0.01) Hypothesized model Rival model Path Estimate Path Estimate IVÆII –0.02 IVÆEP 0.01 SRÆII 0.71** IVÆFG 0.04** IIÆEP 0.78** SRÆEP –0.02 IIÆFG 0.02 SRÆFG 0.04 IIÆEP 0.79** IIÆFG –0.01 χ2 (41)=112.18, p=0.00, GFI=0.92, AGFI=0.87, CFI=0.95 NNFI=0.94, PNFI=0.69 χ2 (37)=102.37, p=0.00, GFI=0.92, AGFI=0.86, CFI=0.96 NNFI=0.94, PNFI=0.63 IV SR II EP FGComposite reliability AVE IV 1 – – SR 0.019 1 0.85 0.66 II –0.012 0.517** 1 0.76 0.53 EP 0.005 0.343** 0.464** 1 0.83 0.63 FG 0.212** 0.089 0.038 0.059 1 – – Social relationship capability ζ 2 0.71** Internal venturing capability ζ 1 Firm performance: Firm growth η3 Firm performance: Expected performance η2 Innovation intensityη1 -0.02 0.78** 0.02  118 Lu-Jui Chen, Chun-Chung Chen & Wen-Ruey Lee Copyright © 2008 SciRes JSSM Figure 3. The Rival Model and the results (all predicted directions are positive as literatures suggested) on the intensity of innovative activity (γ11=-0.02, t-value=-0.86). Hypothesis 1 is thus not supported. With regard to Hypothesis 2, it is found that the external re- sources have a significantly positive effect on the inten- sity of innovative activity (γ12=0.71, t-value=10.23). Thus Hypothesis 2 is supported. So is Hypothesis 3a, that the intensity of innovative activity is significant positively with the expected firm performance (β21=0.78, t-value=8.37). Hypothesis 3b, that the effect of the inten- sity of innovative activity on the financial performance does not have a significant positively prediction, is not supported by this test (β31=0.02, t-value=0.55). Results of the parameter estimate are summarized in Table 3 and showed in Figure 2. Compariso n with a rival model We don’t use the full model because this study argues that the intensity of innovative activities is a key mediate variable for firm performance1. Comparison with a rival model is an important way to assess the power of a speci- fied model [7]. The rival model is showed in Figure 3. Our hypothesized model is based in an elaborate theory that hypothesizes a specific nomological inference of constructs. We thus compared our hypothesized model with the rival model using the following criteria: (1) overall fit, as measured by CFI; (2) percentage of the model’s statistically significant parameters; (3) ability to explain the variance in the outcomes of interest, as meas- ures by square multiple correla tions (SMC) of the focal and outcome variables; and (4) parsimony, as measured by the PNFI [44]. The direct paths of the rival model are supported in much of the literature [9] [16] [49] [63]. However, this study argues that the strategic operational process, which is the intensity of innovative activity, is the critical factor in a firm’s performance. Thus, we do 1 We still tested the fit of the full model. According to the result, estima- tion of full model is no better than the hypothesized model. Hence, we argue that our hypothesized model is an effective model. the comparison to ascertain the effectiveness of the hy- pothesized model. The CFI for the rival model is a little higher than for the hypothesized model (CFI= 0.96 v.s 0.95). In our hy- pothesized model, 50% (or 2 of 4) aspects of the path are significant, whereas only 33% (or 2 of 6) aspects of the path are significant in the rival model. Moreover, little additional explanatory power is gained from the addi- tional two paths in which the increment to SMC is 0.05 (for financial performance). In comparing the models, we see there is a difference in parsimony between the hy- pothesized and rival models (4 versus 6 paths). CFI is not an indicator that accounts for the parsimony difference, so we compare the two models using PNFI. The PNFI of the hypothesized model is 0.69, exceeding the rival’s 0.63. Although there is no guideline to determine what the sig- nificant difference in PNFI values is, we note that a sacri- fice of PNFI value is 91% (from 0.69 to 0.63). We ac- complish a great improvement in parsimony without sac- rificing too much CFI. Hence, a sacrifice is worthy for parsimony. Based on these findings, we acknowledge that this comparison provided added confidence in the constructs of our hypothesized model. The intensity of innovative activity also represents a critical process of advantageous creation as a sufficient predictor for the firm. 5. Discussions Overall, the results of this study provide support for the argument that social relationships (that is, external re- sources of a firm) facilitate the innovative activity of ser- vice firms, and that the innovative activity has a positive effect on the expected firm performance. This finding is robust at the dyadic level. The first finding is consistent with previous studies showing that interorganizational relationships are positively related to innovation intensity. The result also supports theorists who emphasized the Internal venturing ca p abilit y ζ 1 Social relationship capability ζ 2 Innovation intensity ζ3 Firm performance: Expected performance η1 0.01 0.04** –0.02 0.04 0.79** Firm performance: Firm growth η2 -0.01  BBStrategic Capabilities, Innovation Intensity, and Performance of Service Firms 119 Copyright © 2008 SciRes JSSM importance of acquiring external knowledge for product development [71]. It is clear that cooperation and innovation among ser- vice firms are important as operational measures. Here we have the implication that focus on the cooperation be- tween firms will create innovation as well as market op- portunity development. Cooperation creates interfirm benefits that are consistent with the literature on organ- izational advantage. The more interaction they have, the more business possibilities there will be; the more coop- eration they have, the more their market opportunities are likely to be productive. The concept of social relation- ships, therefore, is central to the understanding of innova- tion and value creation [45]. An important point to note is that these productive possibilities need to be fully ex- ploited through a firm’s exchanges and cooperation [43]. On the basis of this argument, it seem reasonable to argue that innovation is better facilitated by interfirm coopera- tion, because the interaction will help a firm to consoli- date existing markets and create new market share and market value. However, our analysis found that the intensity of inno- vation is not influenced by internal resources and may even cause a negative effect, although it is non-significant. This is contrary to our argument and it is interesting to discuss. In theory, human resources will be positively related to firm innovation [63] [71]. But the relationship between the firm’s human resources and innovation is diametrically opposed to what we predicted in Hypothesis 1. We infer the reasons for this result as follows: (1) We didn’t measure the organizational climate. Some people would be frustrated by a chaotic environment and seek some sort of stability to improve efficiency of the status quo. Others would be frustrated by the long list of unreal- ized opportunities for improvement. Service firms are located in a competitive market, which affects a firm’s business orientation. (2) The codifiability of the knowl- edge assets is the other reason. Knowledge is embedded on the employee [49]. Service innovations sometimes are easier to create by codifiable knowledge than relatively tacit. All knowledge assets are codifiable to varying de- grees [36]. All else being equal, the knowledge assets on the employee are codifiable mostly that make the insig- nificant effect. (3) RBV focuses on the firm-level analysis and our measures of the latent variables are also likely to represent firm-level information (archival data consists of firms’ information). Furthermore, innovation is needed to narrow down to the refined or specific level. A firm is composed of dif- ferent kind of divisions, and innovation often rests with specific divisions or individuals [49]. Therefore, for ex- ample, we asked managers to respond regarding the in- novative activity and that may cause bias between the two kinds of measures. (4) The type of innovation should be considered further. Innovation can be subdivided into radical and incremental. A large number of radical inno- vations spring from autonomous strategic behavior, while the greatest percentage of incremental innovations come from induced strategic behavior [59]. Therefore, em- ployee is the reasons for why cause an unwilling result according to the different types of innovation [62]. Cer- tainly, all these reasons may help explain the negative result of Hypothesis 1. The path from internal resources to the intensity of innovative activity should be addressed specifically in future study. We also examined the relationship among the three la- tent variables regarding the intensity of innovative activ- ity and the two kinds of firm performance. We showed how the mediate variable contributed to the firm’s per- formance. While the intensity of innovative activity is related positively to the expected firm performance, con- tradicting to the prediction, there is a non-significant ef- fect between innovation and financial performance. In- ternally developed innovations result from deliberate ef- forts. Most successful firms develop both radical and in- cremental innovations over time. Although critical to long-term competitiveness and performance, the out- comes of investments in innovative activities are uncer- tain and often not achieved in the short term, meaning that patience is required as firms evaluate the outcomes of their innovation efforts [6][48]. Therefore, we infer that innovation is an activity for future business and future growth but not on the instant. Thus Hypothesis 3a is sup- ported. Financial performance shows that the last year’s business outcome was not positively influenced by inno- vation, so Hypothesis 3b is not supported. 6. Conclusions and Future Research Direc- tion The view of strategic capabilities presented here includes proprietary resources that exist within a firm and social capital located among firms. To enhance efficiency and effectiveness of the intensity of innovative activities, co- operation between firms is the most important factor. The study results suggest that innovative activity should be integrated into managerial considerations, and that it is a critical process for firm performance. This study finds that the roots of innovation of a service firm are deeply embedded in social relationships. Second, this study also identifies that innovation is a business activity for the future. Service firms intend to innovate new products and processes, and create new market opportunities so as to sustain competitive advantage. Therefore, a firm’s strat- egy underlies its theory of how to compete in the market successfully. Whether it is deliberate or emergent strategy, a firm generally needs to address in the best operational way what the critical economic processes in an industry or market are and how it can take advantage of these to generate competitive advantage for itself [9]. In conclu- sion, service firms experience a competitive advantage when their actions create economic value and when other competitors cannot pursue the same activity. This study  120 Lu-Jui Chen, Chun-Chung Chen & Wen-Ruey Lee Copyright © 2008 SciRes JSSM also found evidence for the suggestion that firms that in- vest more in cooperative relationships share value and common benefits. Moreover, they also need to encourage the development of strong personal and team relation- ships, a high level of trust and strong connections across porous boundaries [16][45][65]. The hypothesized framework this study develops could offer a useful ground for advanced tests of different phenomena. There are several limitations in this study. First, the service firms’ context of this study limits its potential generalizability for respective industries. Service firms include diverse businesses such as advertising, network information supply services, and so on. More studies fo- cusing on different categories of service firms may shed light on the generalizability of the theoretical position developed here. Second, it is possible that the causality may flow in opposition to that proposed here. For exam- ple, perhaps the concern about the intensity of innovative activity promotes social interaction. Although we have built our hypotheses upon existing theories and past ar- guments, future research may show that reserve or inter- active relationships exist. Third, the model was tested empirically in a Taiwanese sample. Therefore, future study in this area could replicate this study and extend it to other economic systems to see if the findings would be similar to those reported here. Finally, the interaction between internal resource advantage and social relation- ship advantage may constitute another direction for future study. This study offers interesting findings and contrib- utes to the understanding of the strategic capabilities and innovation intensity of service firms. REFERENCES [1] P.S. Adler and S.-W. Kwon, “Social capital: prospects for a new concept”, Academy of Management Review 27(1), 2002, pp.17-40. [2] S. Agarwal and S.N. Ramaswami, “Choice of foreign market entry mode: impact of ownership, location and internalization factors”, Journal of International Business Studies 23(1), 1992, pp.1-28. [3] Alam, “An exploratory investigation of user involvement in new service development”, Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 30(3), 2002, pp.250-261. [4] R. Amit and P.J.H. Schoemaker, “Strategic asset and or- ganization rent”, Strategic Management Journal 14(1),1993, pp.33-46. [5] U. Andersson, M. Forsgren and U. Holm, “Subsidiary embeddedness and competence development in MNCs-A multi-level analysis”, Organization Studies 22(6), 2001, pp.1013-1034. [6] U. Andersson, M. Forsgren and U. Holm, “The strategic impact of external networks: subsidiary performance and competence development in the multinational corpora- tion”, Strategic Management Journal 23(11), 2002, pp.979-996. [7] R.P. Bagozzi and Y. Yi, “On the evaluation of structural equation models”, Academy of Marketing Science 16(1), 1998, pp.74-94. [8] J.B. Barney, “Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage”, Journal of Management 17(1), 1991, pp.99-120. [9] Barney, J.B., Gaining and Sustaining Competitive Advan- tage, 3rd, Prentice Hall, 2006. [10] Bell, D., The Coming of Post-Industrial Society: A Ven- ture in Social Forecasting: Basic Books, Reissue edition, 2001. [11] Burt, R.S., Structural Holes: the Social Structure of Com- petition, Cambridge. MA: Harvard University Press, 1992. [12] H.-J. Cho and V. Pucik, “Relationship between innovation, quality, growth, profitability, and market value”, Strate- gic Management Journal 26(6), 2005, pp.555-575. [13] W.M. Cohen and D.A. Levinthal, “Absorptive capacity: a new perspective on learning and innovation”, Administra- tive Science Quarterly 35(1), 1990, pp.128-152. [14] I. Dierickx and K. Cool, “Asset stock accumulation and sustainability of competitive advantage”, Management Science 35(12), 1989, pp.1504-1514. [15] Doz , Y.L. and G. Hamel, Alliance Advantage. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press, 1998. [16] Dyer, J.H., Collaborative Advantage: Winning through Extended Enterprise Supplier Networks. New York: Ox- ford University Press, 2000. [17] I. Ekeledo and K. Sivakumar, “International market entry mode strategies of manufacturing firms and service firms: a resource-based perspective”, International Marketing Review 21(1), 2004, pp.68-101. [18] M.K. Erramilli, “Entry Mode Choice in Service Indus- tries”, International Marketing Review 7(5), 1990, pp.50-62. [19] M.K. Erramilli and C.P. Rao, “Service firms' international entry-mode choice: a modified transaction-cost analysis approach”, Journal of Marketing 57(3), 1993, pp.19-38. [20] C. Fornell and D.F. Larcker, “Evaluating structural equa- tion models with unobservable variables and measure- ment error”, Journal of Marketing Research 18(1), 1981, pp.39-50. [21] C. Freeman and J. Hagedoorn, “Catching up or falling behind: patterns in international interfirm technology partnering”, World Development 22(5), 1994, pp.771-780. [22] M.S. Granovetter, “Economic action and social structure: the problem of embeddedness”, American Journal of So- ciology 91(3), 1985, pp.481-510. [23] M.S. Granovetter, “The strength of weak ties”, American Journal of Sociology 78(6), 1973, pp. 1360-1380. [24] R.M. Grant, “The resource-based theory of competitive advantage: implications for strategy formulation”, Cali- fornia Management Review 33(2), 1991, pp.114-135. [25] R. Gulati, “Alliance and networks”, Strategic Manage- ment Journal 19(4), 1998, pp.293-318. [26] G. Hamel, “Competition for competence and inter partner learning within international strategic alliances”, Strate- gic Management Journal 12(summer special issue), 1991, pp.83-103.  BBStrategic Capabilities, Innovation Intensity, and Performance of Service Firms 121 Copyright © 2008 SciRes JSSM [27] J. Han, N. Kim and R. Srivastava, “Market orientation and organisational performance: is innovation a missing link?”, Journal of Marketing 62(4), 1998, pp.30-46. [28] T. Hennig-Thurau, K.P. Gwinner and D.D. Gremler, “Understanding relationship marketing outcomes: an in- tegration of relational benefits and relationship quality”, Journal of Service Research 4(3), 2002, pp.230-247. [29] T. Hennig-Thurau, G. Walsh and O. Wruck, “An investi- gation into the factors determining the success of service innovations: the case of motion pictures”, Academy of Marketing Science Review 6(1), 2001, pp.1-23. [30] M.A. Hitt, R.E. Hoskisson and R.D. Ireland, “Mergers and acquisitions and managerial commitment to innovation in M-Form firms”, Strategic Management Journal 11(special issue), 1990, pp.29-47. [31] M.A. Huselid, “The impact of human resource manage- ment practices on turnover, productivity, and corporate financial performance”, Academy of Management Journal 38(3), 1995, pp.635-672. [32] A.C. Inkpen, “A note on the dynamics of learning alli- ances: competition, cooperation, and relative scope”, Strategic Management Journal 21(7), 2000, pp.775-779. [33] Jackson, S.E., A. DeNisi and M.A. Hitt, Managing Knowledge for Sustained Competitive Advantage: De- signing Strategies for Effective Human Resource Man- agement: Pfeiffer, 2003. [34] P.V. Kale, H. Singh and H. Perlmutter, “Learning and protection of proprietary assets in strategic alliances: building relational capital”, Strategic Management Jour- nal 21(3), 2000, pp.217-237. [35] B. Kogut, “Joint ventures: theoretical and empirical per- spectives”, Strategic Management Journal 9(4), 1988, pp.319-332. [36] B. Kogut and U. Zander, “Knowledge of the firm, combi- native capabilities, and the replication of technology”, Organization Science 3(3), 1992, pp.383-397. [37] P.J. Lane and M. Lubatkin, “Relative absorptive capacity and interorganizational learning”, Strategic Management Journal 19(5), 1998, pp.461-477. [38] J.N. Larsen, “Knowledge, human resources and social practice: the knowledge-intensive business service firm as a distributed knowledge system”, The Service Industries Journal 21(1), 2001, pp.81-102. [39] A. Leiponen,“Organization of knowledge and innovation: the case of Finnish business services”, Industry and In- novation 12(2), 2005, pp.185-203. [40] H. Littunen and T. Tohmo, “The high growth in new metal-based manufacturing and business service firms in Finland”, Small Business Economics 21(2), 2003, pp.187-200. [41] J.G. March, “Exploration and exploitation in organiza- tional learning”, Organization Science 2(1), 1991, pp.71-87. [42] B. Menguc and S. Auh, “Creating a firm-level dynamic capability through capitalizing on market orientation and innovativeness”, Academy of Marketing Science 34(1), 2006, pp.63-73. [43] P. Moran and S. Ghoshal, “Markets, firms, and the process of economic development”, Academy of Management Review 24(3), 1999, pp.390-412. [44] R.M. Morgan and S.D. Hunt, “The commitment-trust the- ory of relationship marketing”, Journal of Marketing 58(3), 1994, pp.20-38. [45] J. Nahapiet and S. Ghoshal, “Social capital, intellectual capital, and the organizational advantage”, Academy of Management Review 23(2), 1998, pp.242-266. [46] J. Narver and S.F. Slater, “The effect of a market orienta- tion on business profitability”, Journal of Marketing 54(4), 1990, pp.20-35. [47] I. Nonaka, “The knowledge-creating company”, Harvard Business Review 69(6), 1991, pp.96-104. [48] A. Ozsomer, R. Calantone and A.D. Benedetto, “What makes firms more innovative? a look at organizational and environmental factors”, Journal of Business and In- dustrial Marketing 12(6), 1997, pp.400-416. [49] E.T. Penrose, The Theory of the Growth of the Firm, 3rd, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995. [50] P.D.S. Perez and J.M.G. Falcon, “The influence of human resource management in savings bank performance”, The Service Industries Journal 24(2), 2004, pp.51-66. [51] M.A. Peteraf, “The cornerstones of competitive advantage: a resource based view”, Strategic Management Journal 14(3), 1993, pp.179-191. [52] M.E. Porter, Competitive Advantage: Creating and Sus- taining Superior Performance, New York: The Free Press,1985. [53] C.K. Prahalad and G. Hamel, “The core competence of the corporation”, Harvard Business Review 68(2), 1990, pp.79-91. [54] C.K. Prahalad and V. Ramaswamy, “Co-opting customer competence”, Harvard Business Review 78(1), 2000, pp.79-87. [55] K. Provan, “Interorganizational cooperation and decision making autonomy in a consortium multihospital system”, Academy of management Review 9(3), 1984, pp.494-504. [56] L. Raymond and J. St-Pierre, “Customer dependency in manufacturing SMEs: implications for R&D and per- formance”, Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development 11(1), 2004, pp.23-33. [57] C.A. Romano, “Identifying factors which influence prod- uct innovation: a case study approach”, Journal of Man- agement Studies 27(1), 1990, pp.75-95. [58] R.W. Schmenner, “Service businesses and productivity”, Decision Sciences 35(3), 2004, pp.335-347. [59] Schumpeter, J.A., The Theory of Economic Development: An Inquiry into Profits, Capital, Credit, Interest and the Business Cycle, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1934. [60] C. Styles and T. Ambler, “The impact of relational vari- ables on export performance: an empirical investigation in Australia and the UK”, Australian Journal of Man- agement 25(3), 2000, pp.261-281. [61] M. Subramaniam and M.A. Youndt, “The influence of intellectual capital on the types of innovative capabilities”, Academy of Management Journal 48(3), 2005, pp.450-463. [62] D. A. Subramanian and S. Nilakanta, “Organizational  122 Lu-Jui Chen, Chun-Chung Chen & Wen-Ruey Lee Copyright © 2008 SciRes JSSM innovativeness: exploring the relationship between or- ganizational determinants of innovation, types of innova- tions, and measures of organizational performance”, Omega 24(6), 1996, pp.631-647. [63] D.J. Teece, G. Pisano and A. Shuen, “Dynamic capabili- ties and strategic management”, Strategic Management Journal 18(7), 1997, pp.509-533. [64] Thompson, A.J., J.E. Gamble and A.J. Strickland, Strategy: Winning in the Marketplace: Core Concepts, Analytical Tools, Cases, 2nd, McGraw-Hill/Irwin, 2006. [65] W. Tsai and S. Ghoshal, “Social capital and value creation: the role of intrafirm networks”, Academy of Management Journal 41(4), 1998, pp.464-476. [66] M. Tushman and P. Anderson, “Technological disconti- nuities and organizational environments”, Administrative Science Quarterly 31(3), 1986, pp.439-465. [67] Ulrich, D. and D. Lake, Organisational Capability: Com- peting from the Inside Out, New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1990. [68] S.L. Vargo and R.F. Lusch, “Evolving to a new dominant logic for marketing”, Journal of Marketing 68(1), 2004, pp.1-17. [69] F.J.H.M. Verhees and M.T.G. Meulenberg, “Market ori- entation, innovativeness, product innovation, and per- formance in small firms”, Journal of Small Business Management 42(2), 2004, pp.134-154. [70] B. van Ark and M. Piatkowski, “Productivity, innovation and ICT in Old and New Europe”, International Eco- nomics and Economic Policy, 1(2/3), 2004, pp.215-246 [71] von Hippel, E., The Source of Innovation, New York: Oxford University Press, 1988. [72] B. Wernerfelt, “A resource-based view of the firm”, Stra- tegic Management Journal 5(2), 1984, pp.171-180. [73] J.A. Wolff and T.L. Pett, “Small-firm performance: mod- eling the role of product and process improvements”, Journal of Small Business Management 44(2), 2006, pp.268-284. [74] T. Yoshikawa, A.A. Rasheed, D.K. Datta and J. Rosen- stein, “Financial and product market integration: re- sponses of Japanese firms”, Management International Review 46(5), 2006, pp.529-555. |