Paper Menu >>

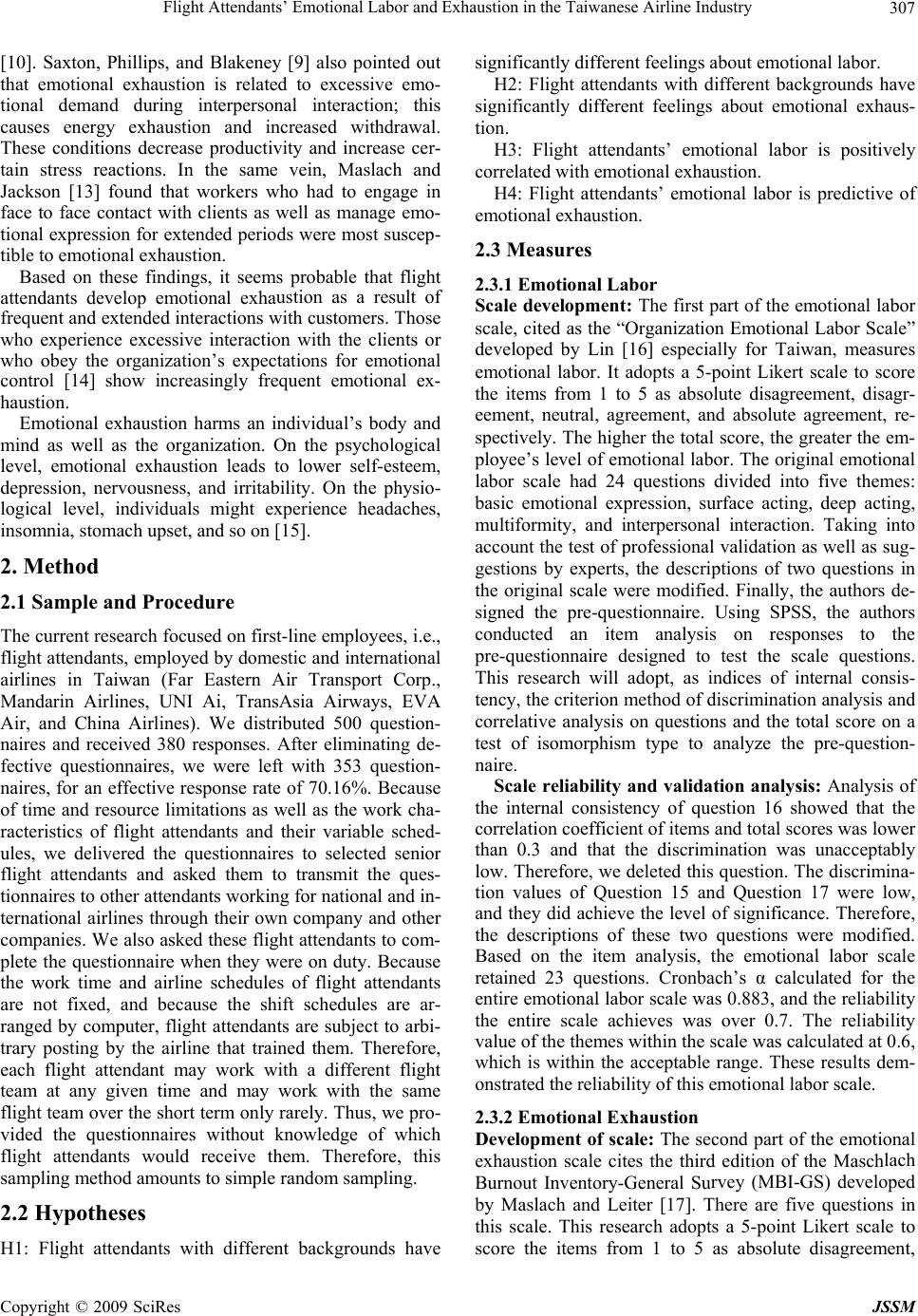

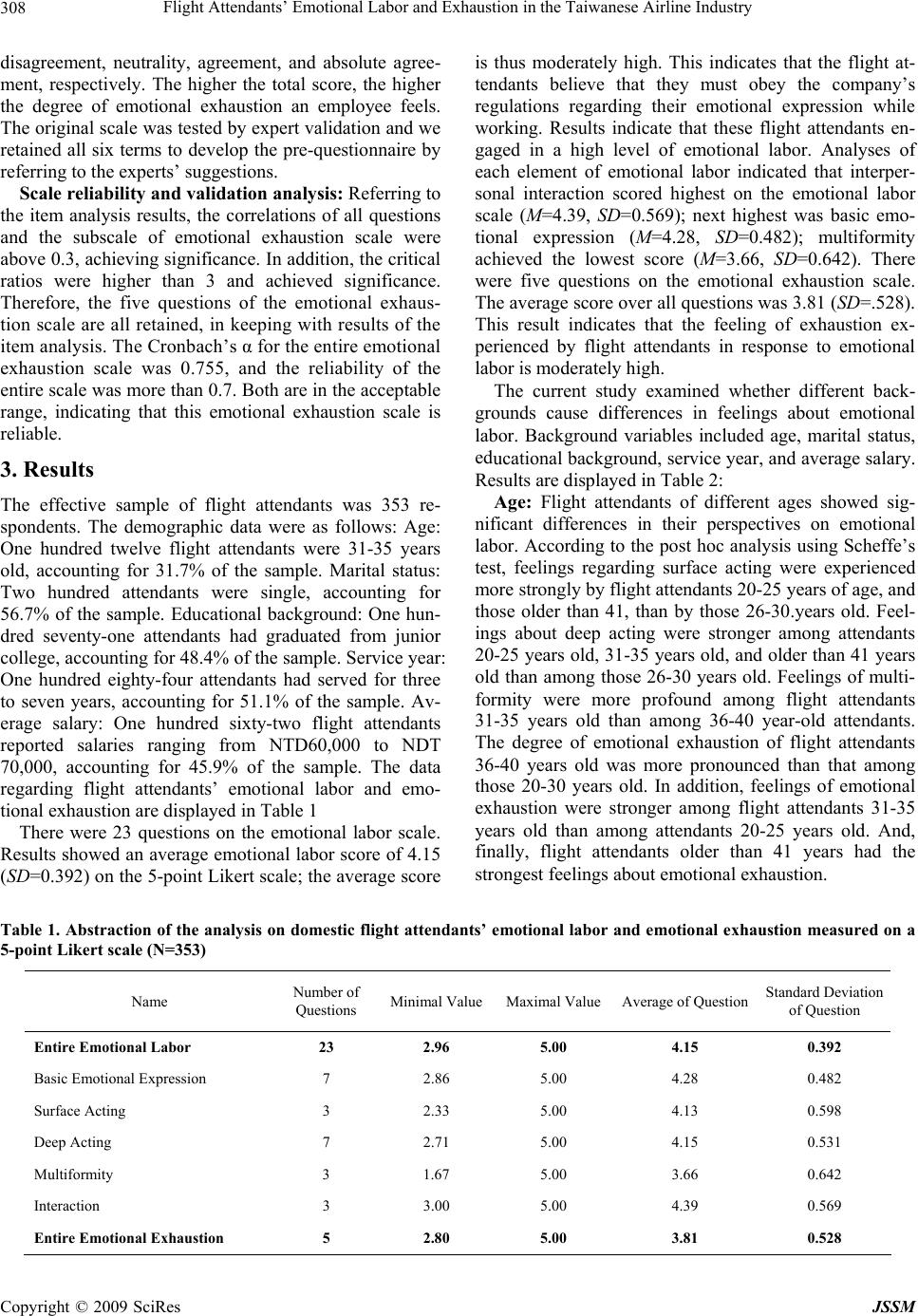

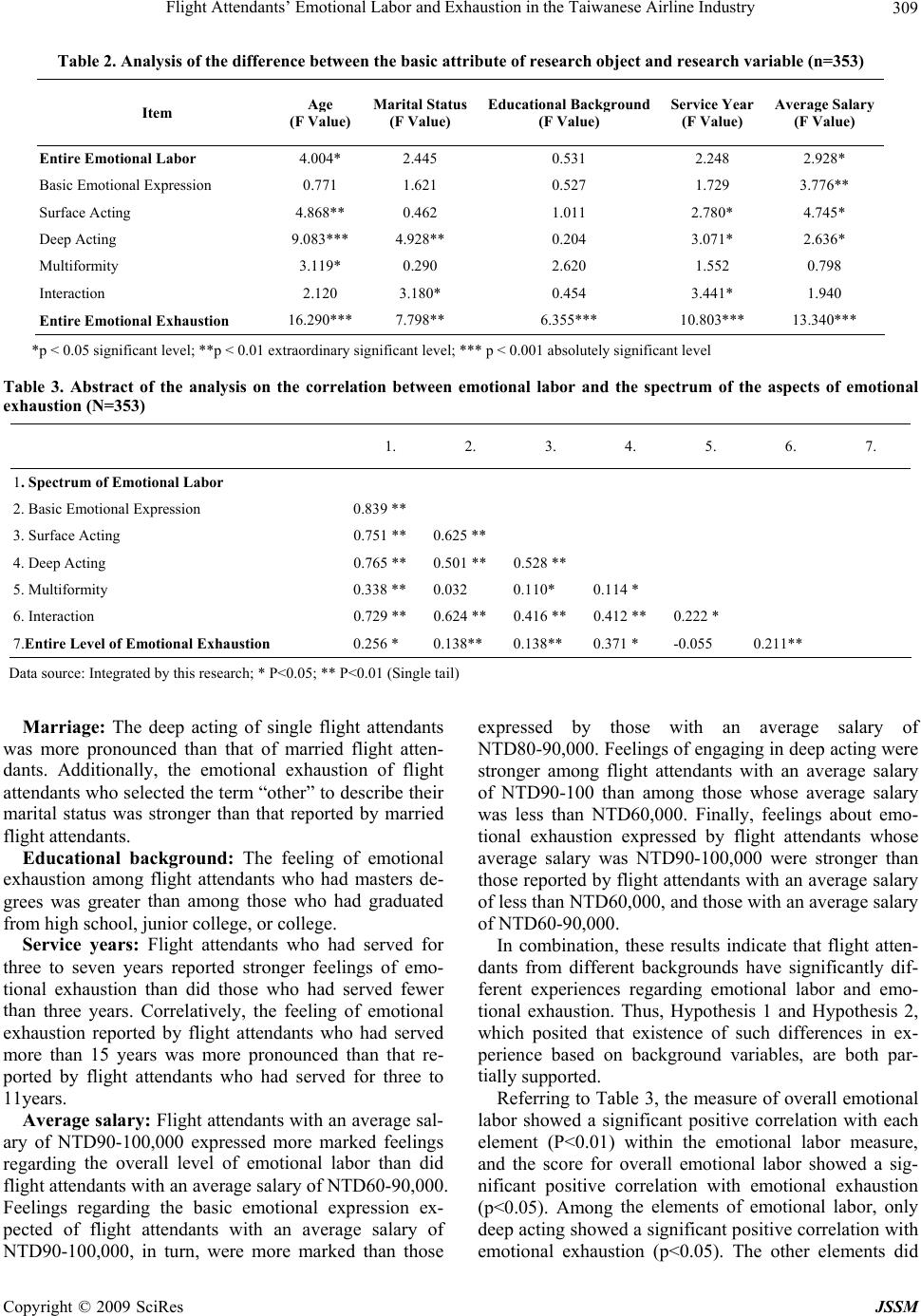

Journal Menu >>

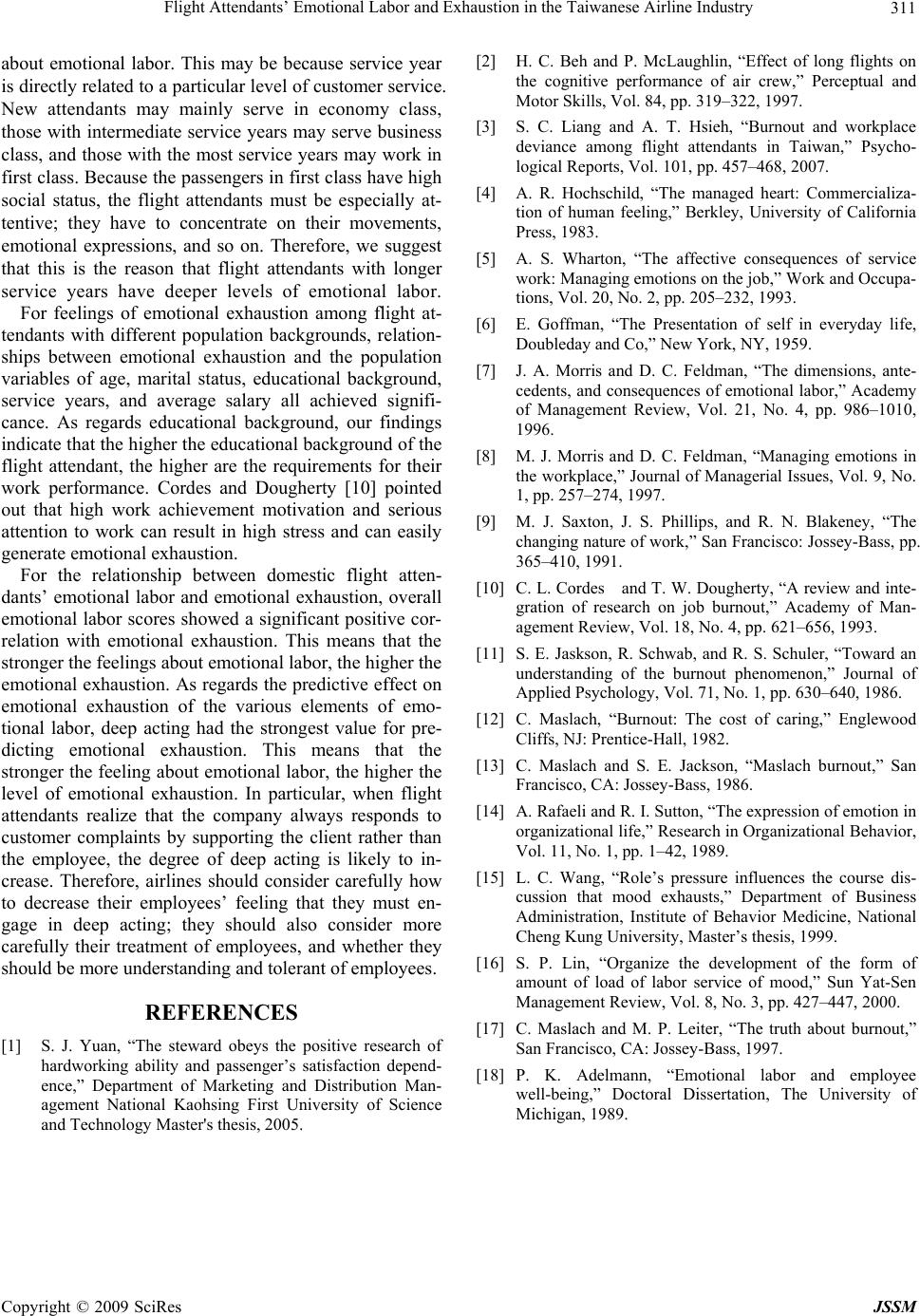

J. Service Science & Management, 2009, 2: 305-311 doi:10.4236/jssm.2009.24036 Published Online December 2009 (www.SciRP.org/journal/jssm) Copyright © 2009 SciRes JSSM 305 Flight Attendants’ Emotional Labor and Exhaustion in the Taiwanese Airline Industry Cheng-Ping CHANG, Ju-Mei CHIU Nan-Tai Street, Yung-Kung City, Taiwan, China Email: justin@mail.stut.edu.tw Received May 2, 2009; revised July 29, 2009; accepted August 4, 2009. ABSTRACT Few research studies have discussed the two variables of emotional labor and emotional exhaustion, and even fewer have examined flight attendants as the research subject. The current study employed a questionnaire method to examine 353 Taiwanese flight attendants’ feelings about emotional labor, the status of their emotional exhaustion, and the rela- tionship between emotional labor and emotional exhaustion. The research results indicate that: 1) while the degree of emotional labor operating on female flight attendants is on the medium to high side, the attendants’ perceptio n of emo- tional exhaustion is only medium; 2) female flight attendants’ emotional labor has a significant positive correlation with their emotional exhaustion; and 3) among the perspectives of emotional labor, the qualities of “deep emotional masking” and “multiformity” have a significant predictive effect on emotio nal exhaustion. Keywords: Flight Attendant, Emotional Labor, Emotional Exhaustion 1. Introduction In recent years, the industrial structure in Taiwan has changed such that the service industry has gradually re- placed traditional manufacturing as the leading industry. Statistical data reported in the Quarterly National Eco- nomic Trends issued by the Directorate-General of Budget, Accounting and Statistics, Executive Yuan, in- dicated that in the third quarter of 2006 the service indus- try accounted for 71.98% of the country’s industry. The airline industry has been part of the service indus- try since the government implemented the open sky pol- icy of airline deregulation in 1987. As a result, many pri- vate airlines entered the market (Liou, 2006). High speed rail opened completely to traffic in 2007, taking away many passengers from airlines in western Taiwan. Un- derstanding that a low price strategy cannot maintain passenger loyalty for any length of time, the airlines have changed their strategy to emphasize improved quality of service and maintenance of flight safety. These strategies encourage passengers to maintain a positive opinion about the airlines and to appreciate the quality of service they provide. Flight attendants constitute the majority of customer- service employees in the airline industry. Compared to their colleagues in other departments, flight attendants have more contact with passengers, and for longer peri- ods of time. Within the airline industry, flight attendants are referred to as the first-line service attendants [1]. Passengers’ images of the airlines are heavily influenced by the manners and emotional attitudes of flight atten- dants. The working environment of flight attendants is noteworthy in that, over time, it will have a negative im- pact on flight attendants’ psychological health. During international service, flight attendants face numerous stresses. They must provide service over a long period of time; the pressure in the aircraft cabin is high and the space is hermetic; the types and temperaments of pas- sengers are complex; and the environment may foster various diseases. Furthermore, the work hours of flight attendants are uncertain, and they often deal with night-shift assignments and time-zone changes. Such anomalous shifts over a long period of time constitute the main influence on the health of flight attendants. Beh & McLaughlin [2] suggested that stress experienced during long flights affects some aspects of mental performance. In addition, the uncertainty of flight attendants’ work schedules limits their private time, potentially causing conflicts between work and family. Additionally, an overly-heavy workload may induce burnout among flight attendants. Such burnout, in turn, increases flight atten- dants’ alienation from work and decrease their sense of connection to the company. Liang & Hsieh [3] suggested a relationship between burnout and workplace deviance, identified as a component of job performance. Too much  Flight Attendants’ Emotional Labor and Exhaustion in the Taiwanese Airline Industry 306 physiological and psychological stress over a long period of time causes lower service quality and a higher turnover rate. Flight attendants have to control their overt behavior and private emotions in order to maintain positive inter- actions with colleagues and passengers. This kind of emotional control is dictated by the job performance rules of the company, and attendants are required to adjust their emotions to the requirements of the job. This is pre- cisely how Hochschild [4] defined “emotional labor.” Engaging in emotional labor over an extended period may cause emotional labor overload and make adjust- ment to work demands difficult. This situation, in turn, may lead to emotional dissonance, that is, a conflict be- tween the attendant’s internal emotions and the organiza- tion’s rules regarding emotional expression. Over an ex- tended period, this may have a negative effect on the em- ployee’s physiology and psychology. Long-term emo- tional stress and relatively intense emotional labor result in emotional exhaustion. (see Figure 1) There have been few research studies on emotional la- bor among Taiwanese flight attendants. This research focuses on flight attendants in Taiwan, addressing their experiences of emotional labor and emotional exhaustion. The goal of this study was to develop suggestions for additional research, provide practical advice for airlines and related management organizations about the man- agement of flight attendants’ emotional labor, and help those in the flight attendant industry better understand the work characteristics of that role. The research objectives are as follows: 1) To understand the status of flight attendants’ emo- tional labor and emotional exhaustion. 2) To examine differences in emotional labor and emo- tional exhaustion among flight attendants from different backgrounds. 3) To explore the relationship between emotional labor and emotional exhaustion among flight attendants. 4) To understand whether flight attendants’ emotional labor predicts emotional exhaustion. 1.1 Emotional Labor The concept of emotional labor was first proposed by Hochschild [4]. She described emotional labor as follows: “Attendants who are in contact with clients over an ex- tended period are required to control their emotions Independent variable: emotional labor Flight attendants’ background variables Dependent variable: emotional exhaustion Figure 1. Research framework during work te facial ex- the Hochschild’s [4] model of emotional la er has ongoing contact with the public in bo express ce range of acceptable emotional expressions is lim otional expres- si r from the pe emotional stress or an environment laden w work burnout, the first ergy and have the sense that they are becoming exhausted time and to display appropria pressions and behaviors. At the same time, the organi- zations’ regulations and salary structure require that these attendants control their emotions to create the work cli- mate that the organization wants.” In order to meet the organization’s expectations for client service, most em- ployees must frequently control their own emotions in such a way as to convey the emotion expected by the organization. Referring to bor, Wharton [5] proposed three work characteristics or perspectives: 1) The work th face to face and conversational exchanges. 2) When working, the employee is expected to rtain emotions that will have the desired influence on others. 3) The ited by employer-imposed regulations. Goffman [6] argued that the form of em on imposed by emotional labor amounted to surface acting. Goffman suggested that emotional labor amounts to a dramatic enactment, one similar to that of an actor who is expected to express emotion in a screenplay. Goffman [6] also posited that, in addition to surface act- ing, workers may choose to modify how they think about their own feelings or to resist conforming to the emo- tional expression as dictated by the external organization. Goffman’s model of emotional labor as drama su- ggests that employees may also adopt “deep acting”. Earlier researchers discussed emotional labo rspectives of high- and low-level emotional labor as proposed by Hochschild [4]. Discussion about these two levels, however, does not completely address the emo- tional labor load and its component factors. The four perspectives proposed by Morris and Feldman [7] lacked the support of empirical research. A test of Morris and Feldman’s [8] approach discovered that, although their model held promise for explaining the capacity for emo- tional labor, it was unable to differentiate causality from correlation in explaining emotional labor and its conse- quences. Long-term ith too much emotional labor may cause emotional ex- haustion, another consequence of emotional labor. When employees have contact with clients for a long time, the heavy emotional load may induce energy exhaustion [9]. This may cause employees to withdraw from their duties and may lead to illness [10,11]. 1.2 Emotional Exhaustion According to the literature on phase of work burnout is emotional exhaustion [12]. Emotional exhaustion occurs when individuals lack en- Copyright © 2009 SciRes JSSM  Flight Attendants’ Emotional Labor and Exhaustion in the Taiwanese Airline Industry307 ustion as a result of fre ell as the organization. On the psychological le nd Procedure first-line employees, i.e., omestic and international H1: Flight attendants with different backgrounds have [10]. Saxton, Phillips, and Blakeney [9] also pointed out that emotional exhaustion is related to excessive emo- tional demand during interpersonal interaction; this causes energy exhaustion and increased withdrawal. These conditions decrease productivity and increase cer- tain stress reactions. In the same vein, Maslach and Jackson [13] found that workers who had to engage in face to face contact with clients as well as manage emo- tional expression for extended periods were most suscep- tible to emotional exhaustion. Based on these findings, it seems probable that flight attendants develop emotional exha quent and extended interactions with customers. Those who experience excessive interaction with the clients or who obey the organization’s expectations for emotional control [14] show increasingly frequent emotional ex- haustion. Emotional exhaustion harms an individual’s body and mind as w vel, emotional exhaustion leads to lower self-esteem, depression, nervousness, and irritability. On the physio- logical level, individuals might experience headaches, insomnia, stomach upset, and so on [15]. 2. Method 2.1 Sample a The current research focused on flight attendants, employed by d airlines in Taiwan (Far Eastern Air Transport Corp., Mandarin Airlines, UNI Ai, TransAsia Airways, EVA Air, and China Airlines). We distributed 500 question- naires and received 380 responses. After eliminating de- fective questionnaires, we were left with 353 question- naires, for an effective response rate of 70.16%. Because of time and resource limitations as well as the work cha- racteristics of flight attendants and their variable sched- ules, we delivered the questionnaires to selected senior flight attendants and asked them to transmit the ques- tionnaires to other attendants working for national and in- ternational airlines through their own company and other companies. We also asked these flight attendants to com- plete the questionnaire when they were on duty. Because the work time and airline schedules of flight attendants are not fixed, and because the shift schedules are ar- ranged by computer, flight attendants are subject to arbi- trary posting by the airline that trained them. Therefore, each flight attendant may work with a different flight team at any given time and may work with the same flight team over the short term only rarely. Thus, we pro- vided the questionnaires without knowledge of which flight attendants would receive them. Therefore, this sampling method amounts to simple random sampling. 2.2 Hypotheses significantly different feelings about emotional labor. H2: Flight attendants with different backgrounds have significantly different feelings about emotional exhaus- tion. H3: Flight attendants’ emotional labor is positively correlated with emotional exhaustion. H4: Flight attendants’ emotional labor is predictive of emotional exhaustion. 2.3 Measures 2.3.1 Emotional Labor The first part of the emotional labor e “Organization Emotional Labor Scale” specially for Taiwan, measures lach rvey (MBI-GS) developed Scale development: scale, cited as th developed by Lin [16] e emotional labor. It adopts a 5-point Likert scale to score the items from 1 to 5 as absolute disagreement, disagr- eement, neutral, agreement, and absolute agreement, re- spectively. The higher the total score, the greater the em- ployee’s level of emotional labor. The original emotional labor scale had 24 questions divided into five themes: basic emotional expression, surface acting, deep acting, multiformity, and interpersonal interaction. Taking into account the test of professional validation as well as sug- gestions by experts, the descriptions of two questions in the original scale were modified. Finally, the authors de- signed the pre-questionnaire. Using SPSS, the authors conducted an item analysis on responses to the pre-questionnaire designed to test the scale questions. This research will adopt, as indices of internal consis- tency, the criterion method of discrimination analysis and correlative analysis on questions and the total score on a test of isomorphism type to analyze the pre-question- naire. Scale reliability and validation analysis: Analysis of the internal consistency of question 16 showed that the correlation coefficient of items and total scores was lower than 0.3 and that the discrimination was unacceptably low. Therefore, we deleted this question. The discrimina- tion values of Question 15 and Question 17 were low, and they did achieve the level of significance. Therefore, the descriptions of these two questions were modified. Based on the item analysis, the emotional labor scale retained 23 questions. Cronbach’s α calculated for the entire emotional labor scale was 0.883, and the reliability the entire scale achieves was over 0.7. The reliability value of the themes within the scale was calculated at 0.6, which is within the acceptable range. These results dem- onstrated the reliability of this emotional labor scale. 2.3.2 Emotional Exhaustion Development of scale: The second part of the emotional exhaustion scale cites the third edition of the Masch Burnout Inventory-General Su by Maslach and Leiter [17]. There are five questions in this scale. This research adopts a 5-point Likert scale to score the items from 1 to 5 as absolute disagreement, Copyright © 2009 SciRes JSSM  Flight Attendants’ Emotional Labor and Exhaustion in the Taiwanese Airline Industry Copyright © 2009 SciRes JSSM 308 addition, the critical ra . The demographic data were as follows: Age: twelve flight attendants were 31-35 years g for 31.7% of the sample. Marital status: is es included age, marital status, ed nalysis using Scheffe’s te Table 1. Abstraction of the analysis on domestic flight attendan 5-point Likert scale (N=353) disagreement, neutrality, agreement, and absolute agree- ment, respectively. The higher the total score, the higher the degree of emotional exhaustion an employee feels. The original scale was tested by expert validation and we retained all six terms to develop the pre-questionnaire by referring to the experts’ suggestions. Scale reliability and validation analysis: Referring to the item analysis results, the correlations of all questions and the subscale of emotional exhaustion scale were above 0.3, achieving significance. In tios were higher than 3 and achieved significance. Therefore, the five questions of the emotional exhaus- tion scale are all retained, in keeping with results of the item analysis. The Cronbach’s α for the entire emotional exhaustion scale was 0.755, and the reliability of the entire scale was more than 0.7. Both are in the acceptable range, indicating that this emotional exhaustion scale is reliable. 3. Results The effective sample of flight attendants was 353 re- spondents One hundred old, accountin Two hundred attendants were single, accounting for 56.7% of the sample. Educational background: One hun- dred seventy-one attendants had graduated from junior college, accounting for 48.4% of the sample. Service year: One hundred eighty-four attendants had served for three to seven years, accounting for 51.1% of the sample. Av- erage salary: One hundred sixty-two flight attendants reported salaries ranging from NTD60,000 to NDT 70,000, accounting for 45.9% of the sample. The data regarding flight attendants’ emotional labor and emo- tional exhaustion are displayed in Table 1 There were 23 questions on the emotional labor scale. Results showed an average emotional labor score of 4.15 (SD=0.392) on the 5-point Likert scale; the average score thus moderately high. This indicates that the flight at- tendants believe that they must obey the company’s regulations regarding their emotional expression while working. Results indicate that these flight attendants en- gaged in a high level of emotional labor. Analyses of each element of emotional labor indicated that interper- sonal interaction scored highest on the emotional labor scale (M=4.39, SD=0.569); next highest was basic emo- tional expression (M=4.28, SD=0.482); multiformity achieved the lowest score (M=3.66, SD=0.642). There were five questions on the emotional exhaustion scale. The average score over all questions was 3.81 (SD=.528). This result indicates that the feeling of exhaustion ex- perienced by flight attendants in response to emotional labor is moderately high. The current study examined whether different back- grounds cause differences in feelings about emotional labor. Background variabl ucational background, service year, and average salary. Results are displayed in Table 2: Age: Flight attendants of different ages showed sig- nificant differences in their perspectives on emotional labor. According to the post hoc a st, feelings regarding surface acting were experienced more strongly by flight attendants 20-25 years of age, and those older than 41, than by those 26-30.years old. Feel- ings about deep acting were stronger among attendants 20-25 years old, 31-35 years old, and older than 41 years old than among those 26-30 years old. Feelings of multi- formity were more profound among flight attendants 31-35 years old than among 36-40 year-old attendants. The degree of emotional exhaustion of flight attendants 36-40 years old was more pronounced than that among those 20-30 years old. In addition, feelings of emotional exhaustion were stronger among flight attendants 31-35 years old than among attendants 20-25 years old. And, finally, flight attendants older than 41 years had the strongest feelings about emotional exhaustion. ts’ emotional labor and emotional exhaustion measured on a Name Number of Questions Minimal ValueMaximal ValueAverage of Question Standard Deviation of Question Entire Emotional Labor 2.96 5.00 23 4.15 0.392 Basic Emotional Expression 2.86 5.00 7 4.28 0.482 Surface Acting 3 2.33 5.00 4.13 0.598 Deep Acting 7 2.71 5.00 4.15 0.531 Multiformity 3 1.67 5.00 3.66 0.642 Interaction 3 3.00 5.00 4.39 0.569 Entire Emotional Exhaustion 5 2.80 5.00 3.81 0.528  Flight Attendants’ Emotional Labor and Exhaustion in the Taiwanese Airline Industry309 Analysis of the difference beeen the basic attribute of rh object and research variable (n=353) Table 2. tw esearc Ag Item e Marital StatusEducational Background (F Value) (F Value) (F Value) Service Year Average Salary (F Value) (F Value) Entire Emotional Labor 4. 004*2.445 0.531 2.248 2.928* Basic Emotional Expression 0.771 1.621 0.527 1.729 3.776** Surface Acting 4.868** 0.462 1.011 2.780* 4.745* Deep Acting 9.083*** 4.928** 0.204 3.071* 2.636* Multiformity 3.119* 0.290 2.620 1.552 0.798 Interaction 2.120 3.180* 0.454 3.441* 1.940 Entire Emotio1 6.290***7 .798**6. 355***10* .803**13* .340** nal Exhaustion *ificant level; **p < 0.01 extra significant level; *** p < 0.001 absolutely significant lp < 0.05 signordinaryevel Tab on tion emotional the spece aspotional exh le 3. Abstract of the analysishe correlatbetweenlabor andtrum of thects of em austion (N=353) 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 1. Spectrum of Emotional La b o r 2. Basic Emotional Expression 0.839 ** .501 ** .528 ** .110* .114 * .412 ** .222 * 3. Surface Acting 0.751 ** 0.625 ** 4. Deep Acting 0.765 ** 00 5. Multiformity 0.338 ** 0.032 00 6. Interaction 0.729 ** 0.624 ** 0.416 ** 00 7.Entire Level of Emotional Exhaust i on 0.256 * 0.138** 0.138** 0.371 * -0.055 0.211** Data source: Integrated by this research; * P<0.05; ** Ple was m ants. Additionally, the emotional exhaustion of flight at than among those who had graduated fr d fewer th the overall level of emotional labor than did fli expressed by those with an average salary of NTD80-90,000. Feelings of engaging in deep acting were stronger among flight attendants with an average salary kground variables, are both par- tia the elements of emotional labor, only de <0.01 (Sing tail) Marriage: The deep acting of single flight attendants ore pronounced than that of married flight atten- d tendants who selected the term “other” to describe their marital status was stronger than that reported by married flight attendants. Educational background: The feeling of emotional exhaustion among flight attendants who had masters de- grees was greater om high school, junior college, or college. Service years: Flight attendants who had served for three to seven years reported stronger feelings of emo- tional exhaustion than did those who had serve an three years. Correlatively, the feeling of emotional exhaustion reported by flight attendants who had served more than 15 years was more pronounced than that re- ported by flight attendants who had served for three to 11years. Average salary: Flight attendants with an average sal- ary of NTD90-100,000 expressed more marked feelings regarding ght attendants with an average salary of NTD60-90,000. Feelings regarding the basic emotional expression ex- pected of flight attendants with an average salary of NTD90-100,000, in turn, were more marked than those of NTD90-100 than among those whose average salary was less than NTD60,000. Finally, feelings about emo- tional exhaustion expressed by flight attendants whose average salary was NTD90-100,000 were stronger than those reported by flight attendants with an average salary of less than NTD60,000, and those with an average salary of NTD60-90,000. In combination, these results indicate that flight atten- dants from different backgrounds have significantly dif- ferent experiences regarding emotional labor and emo- tional exhaustion. Thus, Hypothesis 1 and Hypothesis 2, which posited that existence of such differences in ex- perience based on bac lly supported. Referring to Table 3, the measure of overall emotional labor showed a significant positive correlation with each element (P<0.01) within the emotional labor measure, and the score for overall emotional labor showed a sig- nificant positive correlation with emotional exhaustion (p<0.05). Among ep acting showed a significant positive correlation with emotional exhaustion (p<0.05). The other elements did Copyright © 2009 SciRes JSSM  Flight Attendants’ Emotional Labor and Exhaustion in the Taiwanese Airline Industry 310 Table 4. Abstract of the stepwise multiple regression analysison each aspect of emotional labor for emotional exhaustion (N=353) Selective Sequence of R2 after Variables Multiple Correlation Coefficient (R) Determination Original Regression Standardized Regression F Value Coefficient (R) 2Regulation Coefficient (β) Coefficient Intercept (Constant Term) 2.526 Deep Acting 0.371 0.137 0.135 5 Multiformity 0.383 0.147 0.142 30.141***-0.081 -0.099* 5.871***0.380 0.382*** *p < 0.05 significant level; *** p < 0.001 absolutely significant level not reance. The correlations amthese ificant positive correlation with each element of emo- relation with over- al abor) predicted criterion variables in the re- gr r can be described rt scale, with the average score being ttendants’ average feeling about the t ahad face contact with clients, and had conversations for longer periods, and with higher frequency. Therefore, flight attendants are also first-line service people in the airline industry [1]. Adleman’s re- fe s have deeper feelings ach significong perspectives are described as follows: The score for overall emotional labor showed a sig- n tional labor (P<0.01). Furthermore, overall emotional labor showed a significant positive cor l emotional exhaustion (p<0.01). Among the elements of emotional labor, only multiformity failed to show a significant correlation with emotional exhaustion ( r = -0.055, p=0.15>0.05); the other elements of emotional labor all showed significant correlations with emotional exhaustion. Finally, the overall measure of emotional labor showed a significant positive correlation with the overall measure of emotional exhaustion. Thus, Hypothe- sis 3, which predicted just such a relationship, was also supported. Referring to the stepwise multiple regression analysis shown in Table 4, the two perspectives labeled deep act- ing and multiformity (from among the five elements of emotional l ession model. The multiple correlation coefficient, R, was 0.383, and its united explanation variance was 0.147, indicating that these two variables explain 14.7% of the entire emotional exhaustion measure. Referring to the results above, deep acting and multiformity have signifi- cant positive and negative predictive capability for emo- tional exhaustion, respectively. Therefore, Hypothesis 4, which posited that flight attendants’ emotional labor would have a significant predictive effect on emotional exhaustion, was also partly supported. 4. Conclusions Referring to Table 1, it appears that domestic flight at- tendants’ feelings about emotional labo using a 5-point Like 4.15. Thus, flight a role of emotional labor in their lives is moderately strong. This result indicates that flight attendants can be classi- fied as workers who engage in a high level of emotional labor. Regarding feelings about various forms of emo- tional labor, the element of emotional labor having to do with interaction showed the strongest effect in the present findings. Compared to colleagues in other departments, search [18] mentioned that worker performance and sat- isfaction were lower among those engaging in high levels of emotional labor than among workers with less emo- tional labor. High levels of emotional labor can easily generate feelings of unhappiness, lack of self-respect, and depression. Therefore, aviation management organiza- tions must consider whether long-term emotional labor will have negative emotional effects on flight attendants. Flight attendants’ feelings about emotional exhaustion can also be described using a 5-point Likert scale, with an average score of 3.81. This indicates that, on average, flight attendants in this study experienced a moderate level of emotional exhaustion. More specifically, exami- nation of the detailed questions regarding emotional ex- haustion revealed that the highest average score was given to the statement, “The whole work day makes me flighttendants ce to fa el tired.” this was followed in importance by the state- ment, “My work makes me feel tired emotionally.” Thus, most flight attendants reported that they felt tired when working for a long period of time. This research high- lights the consequences of the tiring nature of flight at- tendants’ working environment. Take offs and landings are frequent for domestic airlines, which means that flight attendants must repeatedly provide customer service. Thus, it is easy for flight attendants to feel that their work is dull and repetitive. Flight attendants serving interna- tional airline routes have to face a variety of passengers with distinctive needs; thus, the company is stricter about the entire range of services. All of these factors contrib- ute to flight attendants’ feelings of exhaustion when working for a long period of time. Referring to Table 2, findings addressing differences among flight attendants with different background vari- ables and the relationships of these variables to emotional labor and emotional exhaustion indicate that all back- ground variables play a role. Relationships between emo- tional labor and variables of age, marital status, service years, and average salary all reached significance. Flight attendants with longer service year Copyright © 2009 SciRes JSSM  Flight Attendants’ Emotional Labor and Exhaustion in the Taiwanese Airline Industry311 ab ut and workplace ommercializa- of service The Presentation of self in everyday life, abor,” Academy axton, J. S. Phillips, and R. N. Blakeney, “The . Dougherty, “A review and inte- Schwab, and R. S. Schuler, “Toward an ood Organizational Behavior, ences the course dis- s thesis, 1999. burnout,” f out emotional labor. This may be because service year is directly related to a particular level of customer service. New attendants may mainly serve in economy class, those with intermediate service years may serve business class, and those with the most service years may work in first class. Because the passengers in first class have high social status, the flight attendants must be especially at- tentive; they have to concentrate on their movements, emotional expressions, and so on. Therefore, we suggest that this is the reason that flight attendants with longer service years have deeper levels of emotional labor. For feelings of emotional exhaustion among flight at- tendants with different population backgrounds, relation- ships between emotional exhaustion and the population variables of age, marital status, educational background, service years, and average salary all achieved signifi- cance. As regards educational background, our findings indicate that the higher the educational background of the flight attendant, the higher are the requirements for their w [2] ork performance. Cordes and Dougherty [10] pointed out that high work achievement motivation and serious attention to work can result in high stress and can easily generate emotional exhaustion. For the relationship between domestic flight atten- dants’ emotional labor and emotional exhaustion, overall emotional labor scores showed a significant positive cor- relation with emotional exhaustion. This means that the stronger the feelings about emotional labor, the higher the emotional exhaustion. As regards the predictive effect on emotional exhaustion of the various elements of emo- tional labor, deep acting had the strongest value for pre- dicting emotional exhaustion. This means that the stronger the feeling about emotional labor, the higher the level of emotional exhaustion. In particular, when flight attendants realize that the company always responds to customer complaints by supporting the client rather than the employee, the degree of deep acting is likely to in- crease. Therefore, airlines should consider carefully how to decrease their employees’ feeling that they must en- gage in deep acting; they should also consider more carefully their treatment of employees, and whether they should be more understanding and tolerant of employees. REFERENCES [1] S. J. Yuan, “The steward obeys the positive research of hardworking ability and passenger’s satisfaction depend- ence,” Department of Marketing and Distribution Man- agement National Kaohsing First University of Science and Technology Master's thesis, 2005. H. C. Beh and P. McLaughlin, “Effect of long flights on the cognitive performance of air crew,” Perceptual and Motor Skills, Vol. 84, pp. 319–322, 1997. [3] S. C. Liang and A. T. Hsieh, “Burno deviance among flight attendants in Taiwan,” Psycho- logical Reports, Vol. 101, pp. 457–468, 2007. [4] A. R. Hochschild, “The managed heart: C tion of human feeling,” Berkley, University of California Press, 1983. [5] A. S. Wharton, “The affective consequences work: Managing emotions on the job,” Work and Occupa- tions, Vol. 20, No. 2, pp. 205–232, 1993. [6] E. Goffman, “ Doubleday and Co,” New York, NY, 1959. [7] J. A. Morris and D. C. Feldman, “The dimensions, ante- cedents, and consequences of emotional l of Management Review, Vol. 21, No. 4, pp. 986–1010, 1996. [8] M. J. Morris and D. C. Feldman, “Managing emotions in the workplace,” Journal of Managerial Issues, Vol. 9, No. 1, pp. 257–274, 1997. [9] M. J. S changing nature of work,” San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, pp. 365–410, 1991. [10] C. L. Cordes and T. W gration of research on job burnout,” Academy of Man- agement Review, Vol. 18, No. 4, pp. 621–656, 1993. [11] S. E. Jaskson, R. understanding of the burnout phenomenon,” Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 71, No. 1, pp. 630–640, 1986. [12] C. Maslach, “Burnout: The cost of caring,” Englew Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1982. [13] C. Maslach and S. E. Jackson, “Maslach burnout,” San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 1986. [14] A. Rafaeli and R. I. Sutton, “The expression of emotion in organizational life,” Research in Vol. 11, No. 1, pp. 1–42, 1989. [15] L. C. Wang, “Role’s pressure influ cussion that mood exhausts,” Department of Business Administration, Institute of Behavior Medicine, National Cheng Kung University, Master’ [16] S. P. Lin, “Organize the development of the form of amount of load of labor service of mood,” Sun Yat-Sen Management Review, Vol. 8, No. 3, pp. 427–447, 2000. [17] C. Maslach and M. P. Leiter, “The truth about San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 1997. [18] P. K. Adelmann, “Emotional labor and employee well-being,” Doctoral Dissertation, The University o Michigan, 1989. Copyright © 2009 SciRes JSSM |