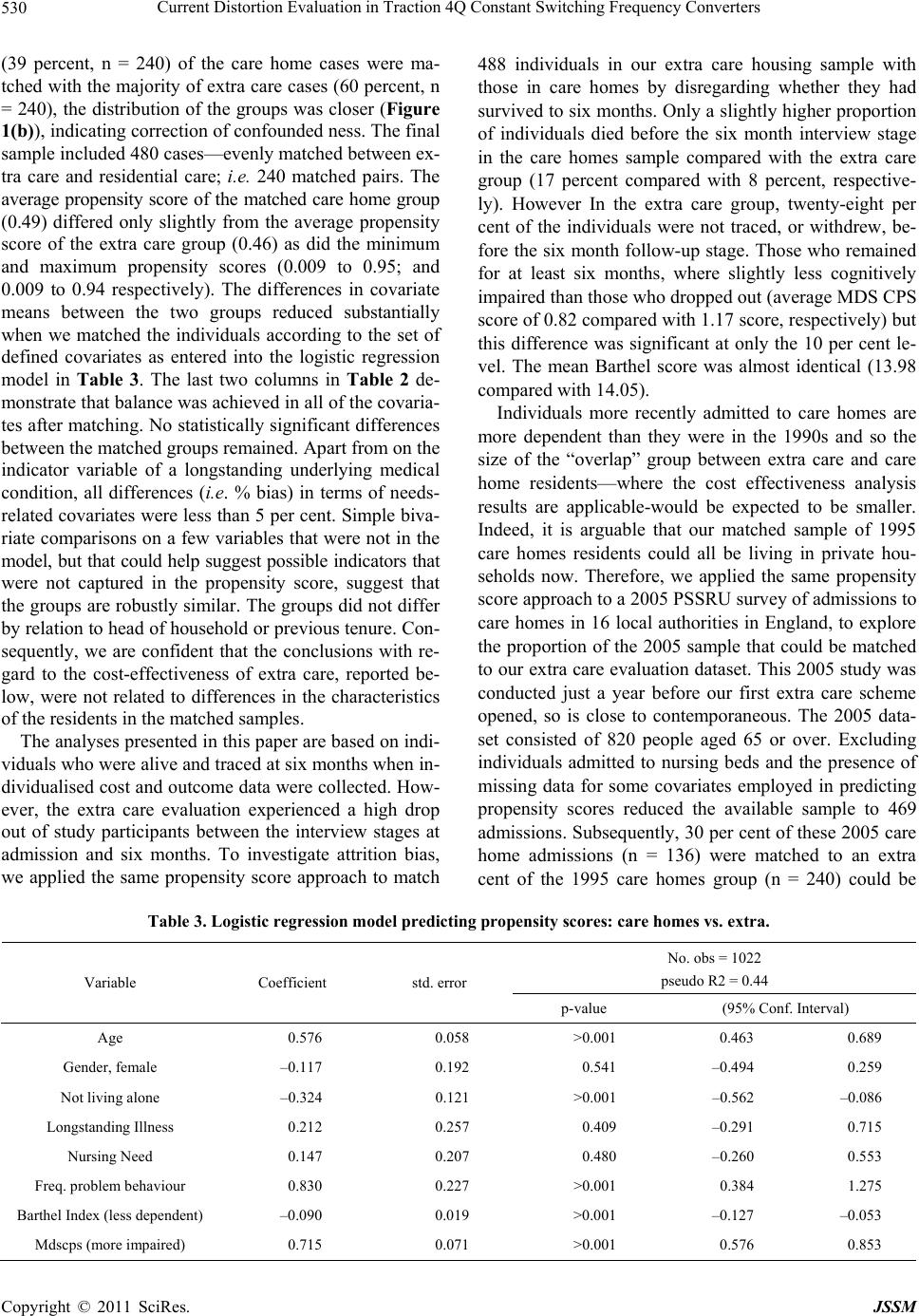

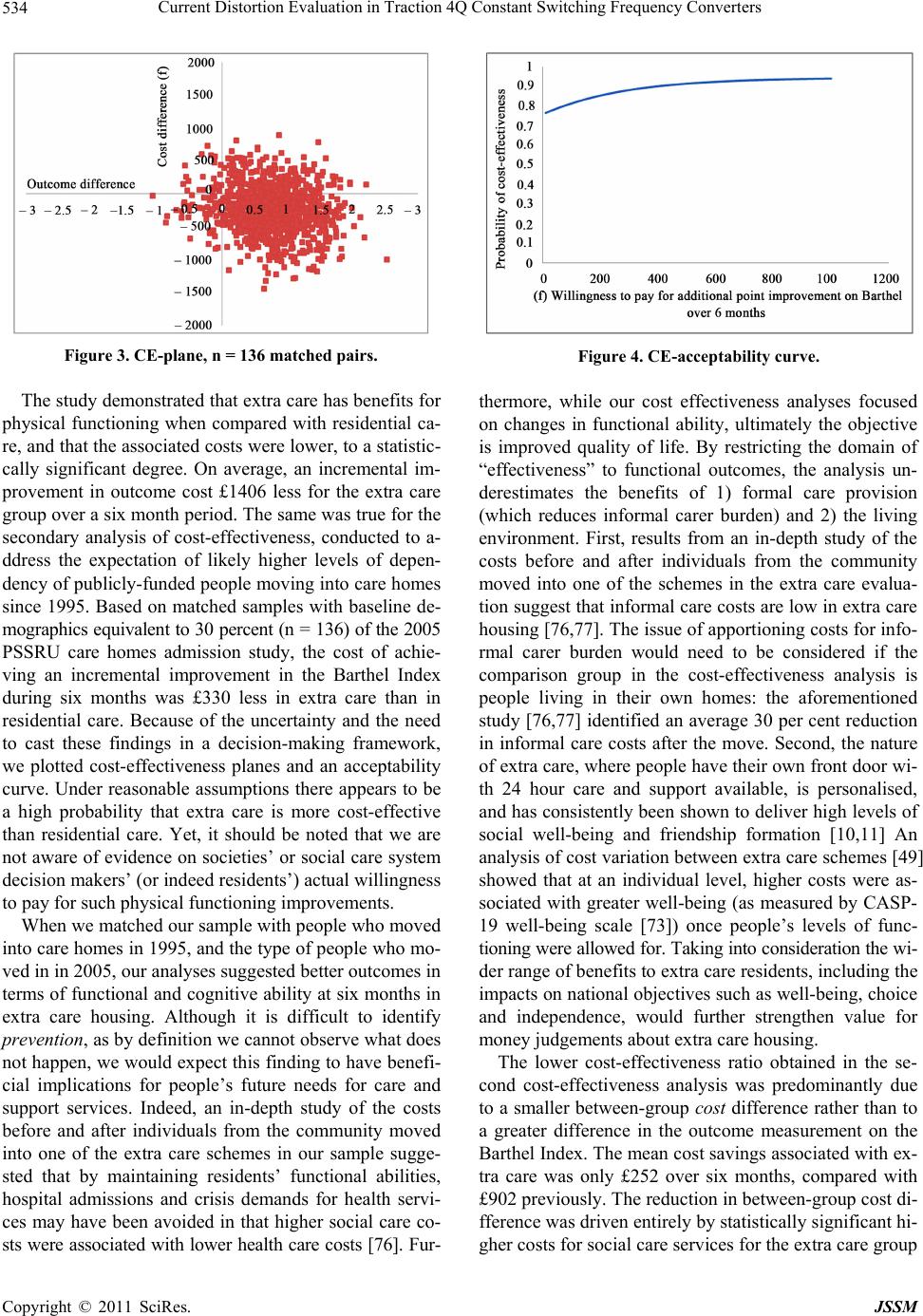

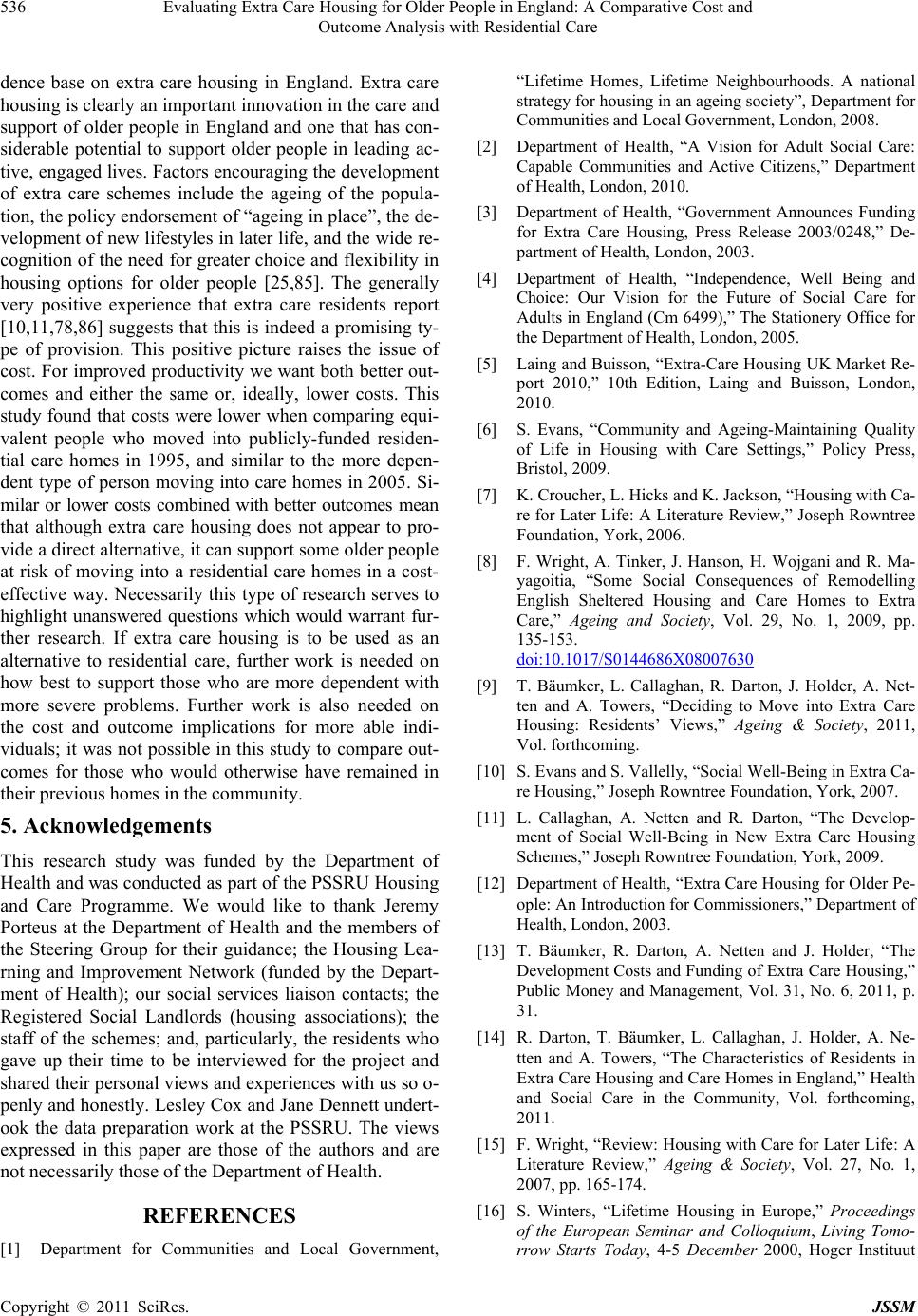

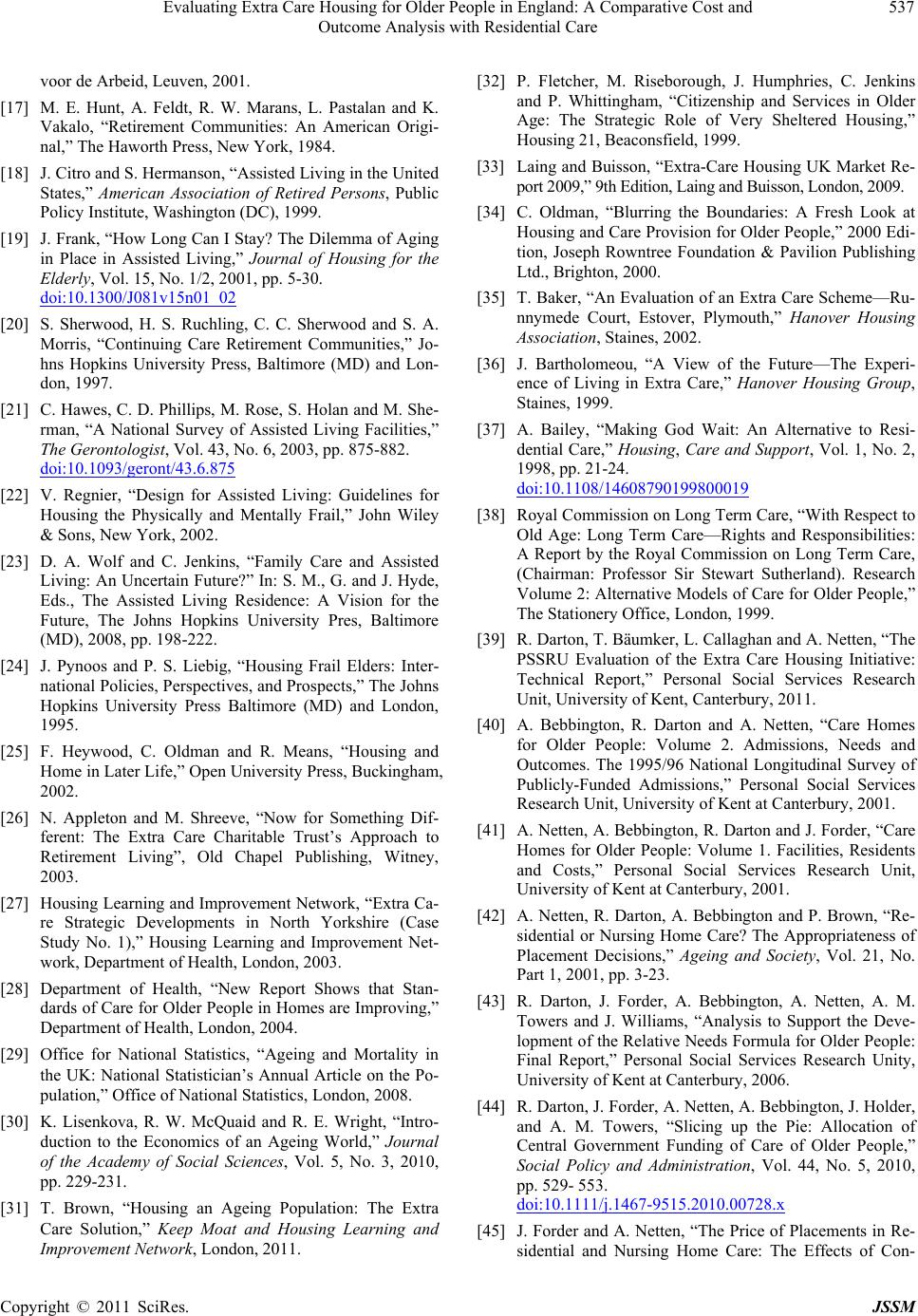

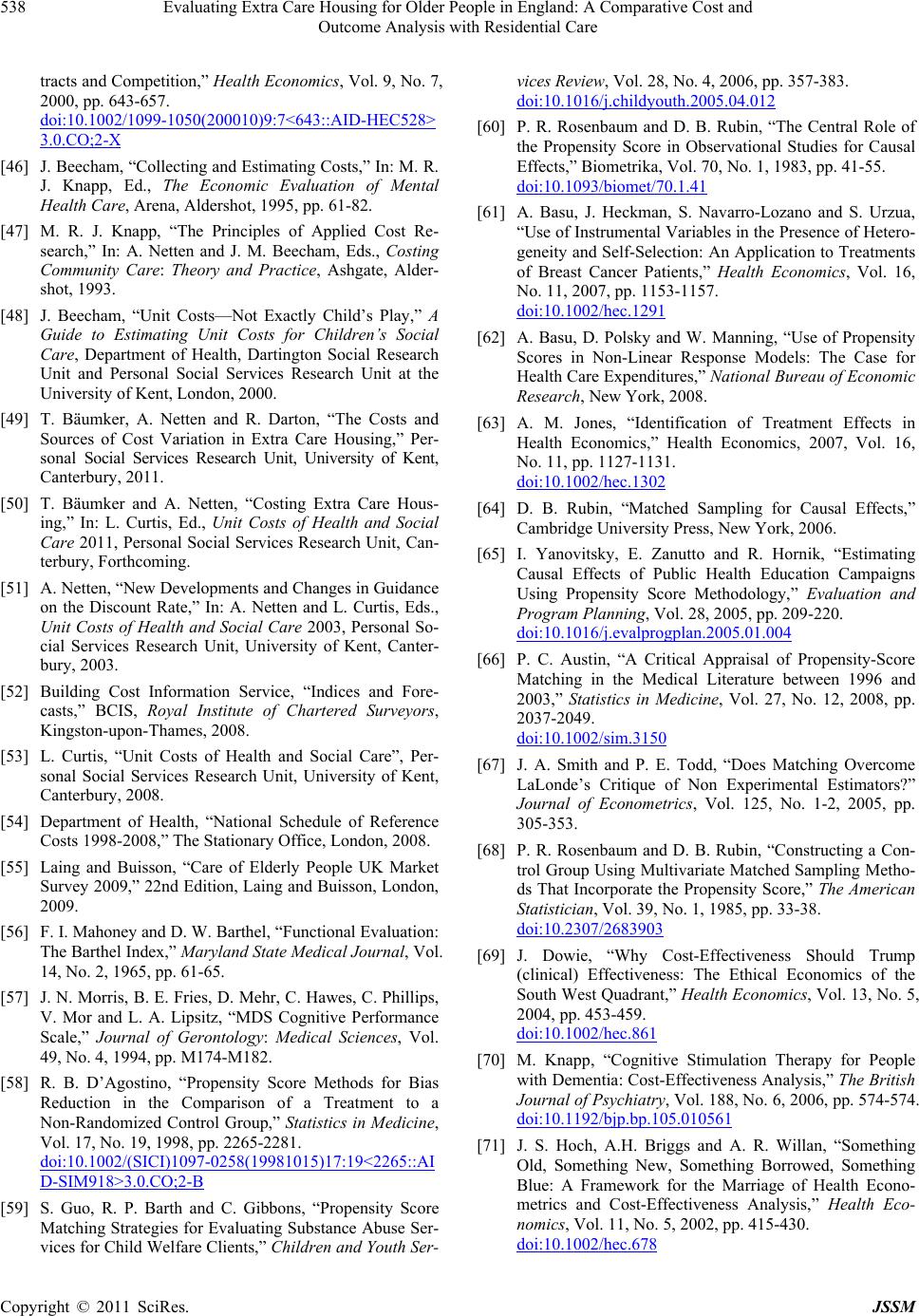

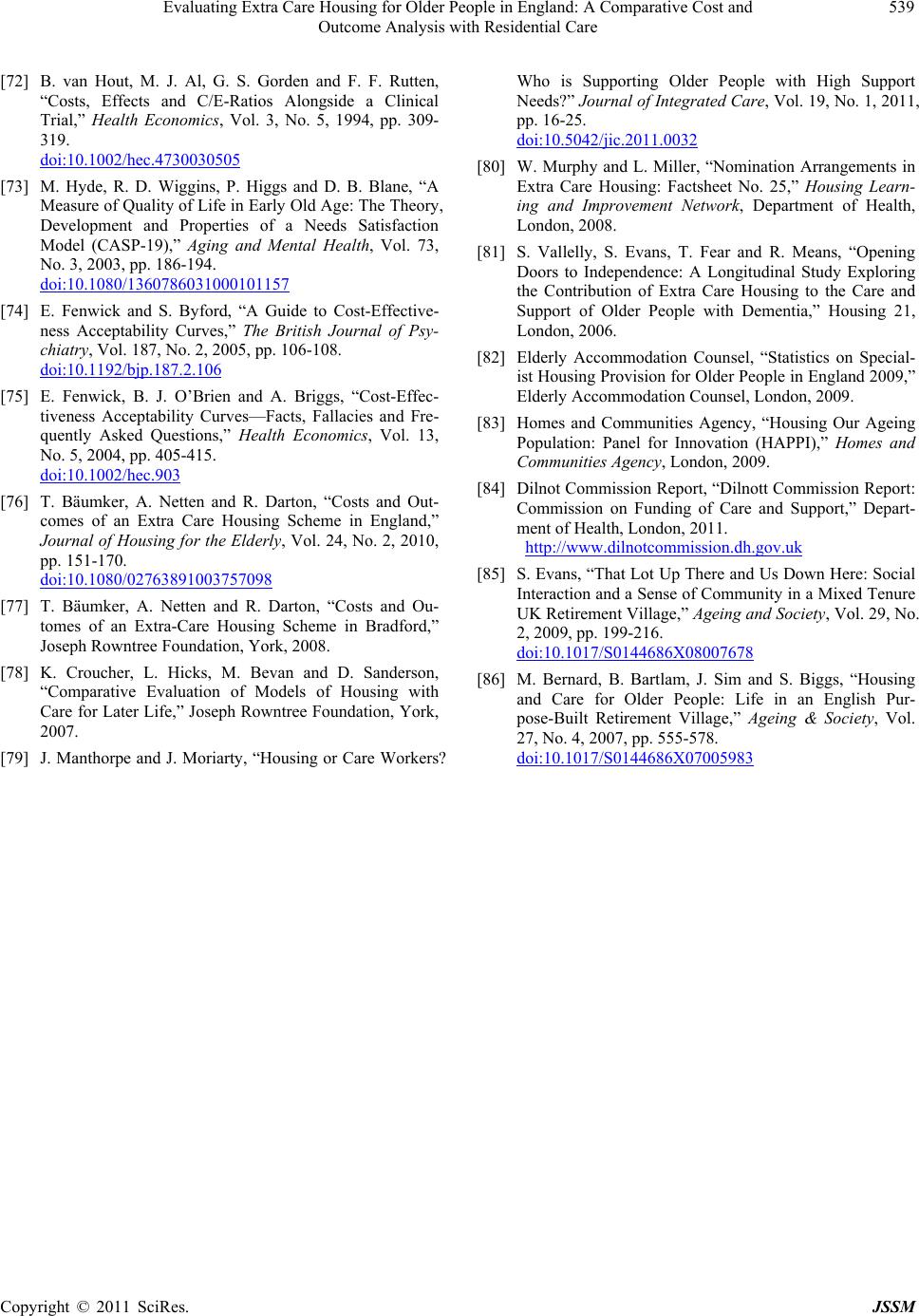

Journal of Service Science and Management, 2011, 4, 523-539 doi:10.4236/jssm.2011.44060 Published Online December 2011 (http://www.SciRP.org/journal/jssm) Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JSSM 523 Evaluating Extra Care Housing for Older People in England: A Comparative Cost and Outcome Analysis with Residential Care Theresia Bäumker, Ann Netten, Robin Darton, Lisa Callaghan Personal Social Services Research Unit, University of Kent, Canterbury, UK. E-mail: t.l.baumker@kent.ac.uk Received October 15th, 2011; revised November 18th, 2011; accepted November 29th, 2011. ABSTRACT Extra care housing is an important innovation in the care and support of older people, and is a housing model that has considerable potential to support older people in leading active, independent lives. Based on cost-effectiveness analyses on statistically matched samples with physical functioning as the primary outcome measure, the study found that costs were lower when comparing equivalent people who moved into publicly-funded residential care homes in 1995, and similar to the more dependent type of person moving into care homes in 2005. Similar or lower costs combined with better outcomes mean that although extra care housing does not appear to provide a direct alternative, it can support some older people at risk of moving into a residential care homes in a cost-effective way. Keywords: Extra Care Housing, Cost Effectiveness, Older People, Long Term Care 1. Background The appropriate response to the housing and care needs of an ageing population is much debated in the policy and practice literature in England [1] , alongside conside- rations of how to ensure affordable and sustainable fun- ding. Extra care housing fulfils national housing planning policy objectives by widening the choice of housing to a- ddress the diverse needs of an ageing society, and also meets community-centred social care policy aims as it pro- motes independent living in one’s own home by provi- ding care and support in purpose-built accommodation. In particular, the personalisation and social care transfor- mation agendas in England emphasise placing individuals at the centre of the process of bringing housing, health and social care together, with the aim of giving people greater choice and control over the services they receive [1,2]. As part of these agendas, the government, in part- nership with the Homes and Communities Agency, suppo- rted the growth of extra care housing through the Depa- rtment of Health’s Extra Care Housing Fund. This Fund provided £227 million capital funding for local authority social services departments and housing associations between 2004 and 2010 in order to stimulate provision of a wide variety of innovative schemes and encourage partnerships in that process [1,3-4]. Although there is no agreed definition, Laing and Bui- sson [5] suggest that extra care housing can be recogni- sed by several characteristics: it is primarily for older peo- ple; the accommodation is self-contained and includes a private kitchen; care can be delivered flexibly, usually by a team of staff based on the premises; support staff are available on the premises for 24 hours a day; domestic care is available; communal facilities and services are available; meals are usually available and charged for when taken; and it aims to be a home for life. In com- parison to care homes in England, extra care housing en- courages independent living in one’s own self-contained dwelling, and offers security of tenure [5]. Extra care hou- sing offers a variety of housing tenures, including rented accommodation and leasehold and shared ownership a- rrangements, and so can enable people to safeguard their financial assets by purchasing or part-purchasing their acco- mmodation. Schemes are intended to support residents with a range of levels of disability, as well as to provide fa- cilities for members of the local community. Smaller ex- tra care schemes typically have 40 or more units of acco- mmodation [6], while retirement villages, typically with more than 100 units [6,7], provide a wider range of social and leisure activities and more accommodation for pur- chase. Individuals are encouraged to move into retire-  Evaluating Extra Care Housing for Older People in England: A Comparative Cost and 524 Outcome Analysis with Residential Care ment villages at a younger age to stimulate the develo- pment of a mixed community of interests and abilities. Many extra care schemes are new-build, although a con- siderable proportion of the smaller schemes have been remodelled from sheltered housing complexes and resi- dential care homes [8]. Remodelling out-dated public se- ctor housing is attractive to many housing providers be- cause England has a legacy of 1960s and 1970s housing which no longer meets older people’s aspirations. A review of the research evidence in the United King- dom (UK) published since 1999 on “housing with care”, an overarching term which includes extra care housing, found that the schemes provide opportunities for social interaction and companionship; that schemes could be an alternative to residential care homes; and that such hou- sing may have a positive impact on health and well-being [7]. Indeed, it could be argued that extra care housing is the embodiment of many of the core principles of current social care policy in England: prevention, personalisation, partnership, plurality and protection [2]. Evidence sugg- ests that older people opt into this type of provision with primarily positive expectations [9], particularly focused on the social aspects of living in the schemes. The nature of extra care, where people have their own front door wi- th 24 hour care and support available, is personalised, lar- gely meeting these expectations: delivering high levels of social well-being and friendship formation [10,11]. The schemes require partnerships between housing providers, local authorities and care providers [12]. Drawing on the expertise of these partners was shown to be particularly helpful in the early developmental stages of schemes in anticipating delays and potential problems [13]. Extra care adds to the plurality or diversity of housing provi- sion, offers an alternative way of living, and provides ba- lanced communities for people with a range of care needs, including those who otherwise would be expected to move into residential care homes [14]. Yet, a remaining open question is whether or not extra care housing has a cost advantage compared with residential care homes [7, 15]. This is, of course, a key question for those who ad- vocate increased investment in the extra care market in the England. Difficulties arise in making international comparisons. There has been more emphasis on housing-based solu- tions for providing accommodation with care in many European countries [16]. However, information about re- sidents is limited. In North America there is a highly de- veloped retirement community industry, dating back to the 1920s [17-20]. More recently, assisted living has been the most rapidly growing form of housing for older pe- ople [21]. Assisted living shares similar characteristics with extra care housing [21,22], but there is substantial variation across states and developments often provide inferior facilities to those expected in England. For exam- ple, 57 per cent of the units were rooms only and 43 per cent were apartments [21]. Wolf and Jenkins [23] found that residents in assisted living had much greater care needs in terms of being able to undertake activities of daily living (ADLs) than people living in the community, but Darton et al. [14] noted that the average level of need in assisted living appeared to be much lower than in a sample of 19 extra care schemes in England. Another im- portant distinction is that purpose-built or age-restricted accommodation in North America, including assisted li- ving, continuing care retirement communities, and, on a larger scale, independent retirement communities, are pre- dominantly provided by the private sector or not-for-pro- fit organizations, and there is little state-funded or federa- lly funded housing provision for older people [24]. In England, however, with its different housing, health, and social care finance system, the majority of residents in extra care schemes evaluated to date have been at least partly funded by the state. Local authorities in England are interested in extra ca- re housing as they seek to maximise the use of non-re- sidential services against a policy background which es- pouses the benefits of ‘ageing in place’ and ‘lifetime ho- mes and lifetime neighbourhoods’ [25], and as they face increasingly tight financial constraints. Local government in England is structured such that Local Authorities (LAs) are charged legally with undertaking a range of functions to specific areas such as providing social care services. Some local authorities have advocated the complete re- provision of care homes by developing extra care hou- sing [26,27], a view encouraged by the previous gover- nment [28]. Since the implementation of the Care Stan- dards Act 2000 and the Regulation of Care (Scotland) Act 2001, the term nursing home in England has been replaced with “care home with nursing”, which describes a home which provides personal care (help with washing, dressing and giving medication), in addition to having a qualified nurse on duty twenty-four hours a day to carry out nursing tasks. Homes where nursing is not provided are generally referred to as “residential care homes, resi- dential care”, or simply “care homes”. Extra care housing is likely to have more of an effect on the provision of re- sidential care homes (providing personal care only), sin- ce “care homes with nursing” will still be needed for re- sidents requiring high levels of nursing or continuous monitoring [5]. One significant policy driver is the high cost of care homes. A cheaper alternative is inevitably attractive to go- vernment, particularly given the projections of a signi- ficant increase in the number of old people. In 2009, 16 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JSSM  Evaluating Extra Care Housing for Older People in England: A Comparative Cost and 525 Outcome Analysis with Residential Care per cent of the UK population was over 65 years of age. It is estimated that by 2032, there will 16.1 million pe- ople aged 65 and over [29], and that by 2050 over a third of the population in Europe will be over 60 years of age. This has generated considerable debate on the “econo- mics of an ageing world”, including the macro-economic consequences of the cost of welfare including subsidised housing [30,31]. However, there are concerns that local authorities may advocate and develop extra care housing merely to tran- sfer their costs to the central government budget [31,32]. The public funding of older people in extra care housing operates through four main channels. These are: Housing Benefit, funded centrally by the Department of Work and Pensions (DWP) and administered through local autho- rities’ housing departments; other welfare benefits; Suppor- ting People programme grant; and the community care budgets of social services departments in local authorities with adult social care responsibilities [5]. Thus, Housing Benefit, which is funded centrally, may pay the bricks- and-mortar element of extra care housing; therefore the local authority’s social services department only pays for the care element, whereas in care homes they would pay the total cost of the placement, only recovering a means- tested contribution from the client (i.e., the client is char- ged such sums as they have been financially assessed as being able to pay). The appeal to ease the pressure on ha- rd-pressed local authority social services budgets by tran- sferring costs to other agencies is obvious [34]. However, transferring costs to other budgets does not equate to cost savings overall. One of the shortcomings of many cost estimates of extra care housing has been to calculate cost transfers rather than economic costs [7]. The limited evidence available to date, does not yet demonstrate that extra care housing offers a cost-effec- tive alternative to care homes, or in fact, to care in the home (i.e. in-home care services) [7]. Studies have most- ly been conducted or commissioned by provider agencies to evaluate their own schemes [35,36], and the informa- tion collected has usually been specific to the particular study, making comparisons difficult. In studies when com- parisons are reported, like is usually not being compared with like, cost models lack transparency and only cash costs are presented, not economic or resource costs. Sma- ller, quite localised studies have often made contentious claims based on accounting or cash costs only [37]. Whe- re cash costs are the focus, conclusions are different, and the complexity and range of funding and charging arran- gements for extra care can lead to cost-shunting and di- storted views about the relative cost of provision. This, in turn, can lead to inefficient allocation of resources. The UK Royal Commission on the Funding of Long Term Care [38] examined the resource costs, as opposed to ca- sh costs, of a variety of scenarios in “very sheltered” ho- using managed by different housing associations. How- ever, the analyses apply only to the particular situations considered, and do not lead to general conclusions about the relative costs of extra care and other forms of care [5]. In the current financial climate it is critical that resources are targeted effectively. To do this we need information about the comparative costs and benefits of alternative courses of action. 2. Methods 2.1. The Samples The data used for the analyses in this paper were ob- tained from the Department of Health funded PSSRU Evaluation of Extra Care Housing [39], the 1995/1996 National Longitudinal Survey of Publicly-Funded Admi- ssions to Care Homes [40-42], and the PSSRU Crossse- ctional Study of Care Home Admissions in 2005 [43,44]. 2.1.1. Evaluation of Extra Care Housing in England 2006-2010 Approximately £60 million of the £87 million capital funding from the 2004 to 2006 Department of Health funding rounds was allocated to 22 local authorities with social services responsibility to work with housing asso- ciation partners to develop a range of new-build extra ca- re housing schemes. A condition of receiving financial support from these first two funding rounds was that the schemes would participate in a national evaluation. Three schemes were dropped because of delays to planned open- ing dates. The remaining 19 schemes included in the eva- luation opened between April 2006 and November 2008. The schemes included three extra care retirement vil- lages, each with approximately 250 units of accommoda- tion, and 16 smaller developments, with between 35 and 75 units. The nineteen schemes were located in eight re- gions in England: five in the Yorkshire and the Humber, four in the South East, three in London, two in both the North East and the East Midlands, and one in each of the North West, West Midlands and East of England. Among the 19 schemes, 16 were purpose-built on brownfield si- tes, five on the sites of previous sheltered housing or housing for older people, one involved re-modelling an existing sheltered housing scheme, and two on the sites of former residential care homes. The schemes were in- nded to support residents with a range of levels of dis- ability/long term conditions, as well as to provide facili- ties for members of the local community. They offered a mixture of housing tenures, including rented accommo- dation, leasehold and shared ownership arrangements. The villages provided relatively more accommodation Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JSSM  Evaluating Extra Care Housing for Older People in England: A Comparative Cost and 526 Outcome Analysis with Residential Care for sale, while seven of the 16 smaller schemes only pro- vided accommodation for rent. A number of the schemes provided intermediate care services, designed to help pe- ople make the transition from hospital care back to their own homes. However, these individuals were not included in the evaluation, which was restricted to householders rather than older people with a short-term stay. In addi- tion, in the villages, a high proportion of new residents moved in without requiring care services, so baseline ass- essment information was not available for them. The three villages accounted for 770 units of accom- modation and the 16 smaller schemes accounted for 716 units, a total of 1486 units. Excluding the accommoda- tion designated for intermediate care, and the accommo- dation in the villages for people who did not require care services, reduced the total to 909 units. In all, 408 indi- viduals were included in the cost-effectiveness analyses reported in this paper, 67 in two villages and 341 in the 16 smaller schemes. The criteria for inclusion of indi- viduals were: 1) having participated in both interview stages at admission and six months when individualised cost and outcome data were collected; and 2) having full information at both these stages in the measures used in the statistical matching procedure. Unfortunately, one of the villages was excluded from the analyses because the research there experienced delays. To ensure later resea- rch stages were completed on time, the six month stage had to be passed over in this village. 2.1.2. National Longitudinal Survey of Publicly-Funded Admissions to Care Homes 1995-1999 The 1995/1996 National Longitudinal Survey of Publi- cly-Funded Admissions to Care Homes focused on the characteristics of newly admitted residents, and their out- comes and costs. Information was collected on 1) their personal characteristics, health and dependency at time of admission, 2) their circumstances prior to admission, 3) their subsequent moves and survival, health and de- pendency at 6, 18, 30 and 42 months after admission, and 5) charges at admission and sources of funding. In all, 614 care home admissions were included in our analyses. The criteria for inclusion of individuals in our study were: 1) having data at admission and at six months to measure changes in outcomes; 2) having full information at both these stages in the measures used in the statistical mat- ching procedure; and 3) having been admitted to a re- sidential care home (providing board and personal care only), and not to a “care home with nursing” (i.e. for- mally called nursing homes). The registration and regula- tion arrangements for care homes and “care homes with nursing” ensure that the latter must use a higher level of, and more costly, staff inputs [45]. Higher unit costs are thus expected for “care homes with nursing”; even when individuals’ dependency may be the same as in residen- tial care homes. 2.2. The Data In the PSSRU Evaluation of Extra Care Housing the exa- mination of costs was guided by several costing prince- ples widely applied in economic evaluations of health and social care; described elsewhere [46-49]. Most im- portantly, costs were measured comprehensively to in- clude as many service components as possible at an indi- vidual level as described in Bäumker and Netten [50]. The opportunity cost of capital was calculated as the an- nuity which depletes the lump sum value over the life- time of the building, commonly estimated at 60 years [46]. The appropriate discount-rate is the one set by HM Treasury for public services in the UK at 3.5 per cent [51]. Current market values were provided by the hous- ing associations or obtained from the relevant District Valuers Office. For properties constructed pre-2008, ca- pital values were uprated to 2008 Quarter 4 prices using the BCIS Tender Price index [52]. To avoid double- counting the cost implications of the capital investment, items such as capital financing and depreciation were re- moved from schemes’ annual income and expenditure a- ccounts when calculating revenue costs. For health and social care expenditure, service receipt information re- ported by residents was combined with appropriate unit cost information. This was primarily obtained from a na- tionally recognised source [53], and where necessary, unit costs were inflated to 2008 price levels using the relevant inflators given in that volume. In comparison, for the 1995-1999 National Longitudi- nal Survey of Publicly-Funded Admissions to Care Ho- mes the gross weekly placement fee, as reported at ad- mission, was the best proxy for cost [40,41]. The weekly contracted price is set so as to represent the total cost to social services for the care provided. The cost of care in a care home is packaged with the accommodation. Inputs from personnel outside the home such as social work care managers are presumed to be quite small [40]. How- ever, this proxy for costs excludes primary health care, hospital and social security costs [40]. To ensure a like- with-like comparison, it was therefore necessary to ex- clude primary health and hospital costs from the extra ca- re cost estimations, as shown in Table 1. However, costs of support and activity provision could be retained be- cause the Care Homes study reported that virtually all care homes organised activity programmes for their resi- dents, predominantly through their staff [41]. These costs obtained from the 1995-1999 study were uprated to 2008 prices using the relevant PSS Pay and Prices Inflators Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JSSM  Evaluating Extra Care Housing for Older People in England: A Comparative Cost and 527 Outcome Analysis with Residential Care Table 1. Cost estimates for extra care (per week). Cost Component No. Mean Std. Dev MinMax Capital, incl. land 240 106.45 21.26 50.93157.12 Housing management 240 53.18 15.25 21.1777.67 Support costs 240 9.81 4.51 2.4122.14 Activities cost 240 0.68 1.32 0.003.52 Social care 240 123.67 120.84 0.00612.00 Health care 240 72.08 119.29 0.00634.29 Living expense 240 80.13 3.26 73.8081.80 Unit Cost per week 240 446.01 191.83 175.361241.70 Unit Cost per week, excl. health cost 240 373.93 130.64 172.29891.52 [53,54], and the resulting figures were in line with care home costs reported in Laing and Buisson’s UK Care Home Report 2009 [55]. A number of identical approaches were used to mea- re levels of need in both studies. Physical functioning was measured by the Barthel Index of Activities of Daily Living [56] with scores ranging from zero (maximum di- sability) to 20 (minimum disability). Cognitive impairment was measured by the Minimum Data Set Cognitive Per- formance Scale (MDS CPS) [57], with scores ranging from zero (intact) to 6 (very severe impairment). An ad- ditional question (adapted from the MDS CPS to com- bine separate symptoms in a single, overall question), concerned the frequency of problem behaviour, such as wandering, physical or verbal abuse. In addition, an indi- cator of medical care needs was included as a dummy va- riable in the analyses, as was an indicator for the presen- ce of a longstanding underlying medical condition. 2.3. Cost-Effectiveness Analysis The aim of this paper is to assess the cost-effectiveness of extra care housing. Ideally, the most valid comparison groups would have been generated by identifying indi- viduals at the point of assessment, who were eligible for extra care housing, but who instead received an alterna- tive intervention, such as a care home placement or addi- tional home care, most appropriate to their needs. How- ever, in the absence of such an ideal study design, we used the next best alternative-historical control individuals and statistical matching. The extra care evaluation was purposefully designed to record information (on all indi- vidual level variables likely to affect effectiveness, re- source utilisation and costs) equivalent to that collected in the 1995-1999 and 2005 PSSRU studies of publicly- funded admissions to care homes [40,43,44]. Both sett- ings (extra care and care homes) support a broad range of care needs, and thus it was hypothesised that the ranges of care need would overlap between settings. The statis- tical propensity score matching methodology described below aims to mimic an ideal study design and identify a group of individuals who could be equally well served in either setting. Propensity score matching (PSM) is an approach that can adjust for baseline imbalances between groups [58- 60]. Estimates of the effects of an intervention derived from observational data are prone to bias in that indi- viduals’ characteristics can be confounded with alloca- tion to an intervention [61-63]. We estimated the condi- tional probability (the propensity score) that any indi- vidual in the two samples (i.e. in the extra care or resi- dential care homes group) might be allocated to residen- tial care given the vector of our defined covariates. The propensity scores were derived by performing a logistic regression. The main limitation of the propensity score matching method [60] is that it conditions on observables [64]: i.e. it can only take account of observed biases [58, 65]. Therefore the choice of conditioning variables in the statistical model predicting propensity scores is of para- mount importance, and is best informed by prior research evidence and theory [59,66,67]. There is an extensive literature on factors characteristic of people entering resi- dential care homes as supported long-term residents. In- formatively, the 1995 National Longitudinal Survey of Publicly-Funded Admissions to Care Homes [40,41] pro- vided a model to predict probability of admission. As the extra care evaluation was designed to collect equivalent information to the 1995 and 2005 PSSRU studies of ad- missions to care homes [43,44], the likelihood that a con- founding factor was left out of our statistical matching methodology was therefore quite low. We tested differ- rent models to determine the most appropriate predictors for predicting the probability of being allocated to resi- dential care. The matching variables used included de- mographic characteristics, physical and cognitive func- tioning variables and previous living arrangements, such as living alone (which proxies the availability of informal support as prior research has shown care decisions to of- ten be family based). The PSM was conducted using the STATA/PSMATCH2 command and was based on near- est neighbour matching with caliper and without repla- cement. As suggested by Rosenbaum and Rubin [68], we used a caliper size one quarter of the standard deviation of the propensity scores; i.e. matches must fall within this predetermined caliper/ range. Appropriateness of match- ing was assessed using standardized differences statistics for continuous variables and differences statistics for non- continuous variables as recommended by Austin [66]. The next step in our analyses was to conduct the cost effectiveness analyses (CEA) to compare the relative costs and outcomes between the two matched samples of Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JSSM  Evaluating Extra Care Housing for Older People in England: A Comparative Cost and 528 Outcome Analysis with Residential Care extra care housing and residential care residents. A ratio of cost difference to outcome difference was computed— the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (or ICER)—on an outcome measure of physical functioning, as measu- red by the Barthel Index of Activities of Daily Living [56]. Extra care housing would then be defined as more cost-effective than residential care if: (a) it is both less costly and more effective or; (b) it is both more costly and more effective, and the decision-maker considers the additional cost to be justified by the improved outcomes or; (c) it is both less costly and less effective and the deci- sion-maker considers the savings achieved to war- rant giving up some outcome difference. If (c) holds, there would need to be careful considera- tion of whether it would be acceptable politically, pro- fessionally and to clients to advocate a treatment that leads to worse health or well-being than previous prac- tice [69,70]. If (b) holds, difficult trade-off questions are raised. It requires the decision-maker to consider whether it is worth incurring the higher costs in order to achieve improved outcomes. If (a) holds (usually described as “dominance”), extra care would both improve the outco- me for service users (measured in this case by physical independence) and save money. It is important that we explore the implications of the inevitable uncertainty associated with any conclusions drawn about relative cost-effectiveness. The difficulty in obtaining the distribution of a ratio has been discussed elsewhere [71]. We used the nonparametric bootstrap method with one thousand replications to express uncer- tainty in two ways. First we represent scatter plots of the simulated cost-effectiveness ratios in a cost-effectiveness plane, linking effectiveness to costs. Second, from the sa- me bootstrap results, an acceptability curve is constru- cted. This reveals the probability that extra care housing is cost-effective relative to residential care, given differ- rent (implicit monetary) values placed on incremental out- come improvements. For a willingness to pay of “λ”, this probability is equal to the proportion of bootstrap sam- ples in which the ratio calculated is less than λ. The curve not only presents another measure of uncertainty that is linked to the overview estimate of the incremental cost- effectiveness ratio [72], but can also reveal the nature of the trade-offs which arise if situation (b) above occurs. 3. Results Table 2 (Column 1) presents baseline demographics and other details for the extra care residents across the 19 schemes for whom cost data was available at the six- month interview stage. The mean age was 77 years, with half of respondents aged between 70 and 85. About two- thirds of residents were female, and consistent with the marital status information, the majority of residents lived alone at the time of the interview. The majority of the residents had previously been living in ordinary housing (70 percent), 20 percent had been living in sheltered or supported housing, and 7 percent had been living in a care home. The mean score of 14.8 on the Barthel Index illustrates residents’ functional ability in terms of perfor- ming activities of daily living (ADLs); approximately 40 per cent of residents had quite low dependency levels, scoring 17 or more on the Barthel. The Barthel Index of Activities of Daily Living scores range from zero (maxi- mum disability) to 20 (minimum disability). The MDS CPS scores indicate that only 3 percent of those who moved into extra care suffered from moderate to severe cognitive impairment, and challenging behaviour was in- frequent for nearly everyone. In terms of residents’ me- dical histories, more than 80 percent were assessed as having an underlying long term condition, but only one- fifth of residents needed some form of nursing care . The mean score on the CASP-19 scale [73], for which higher scores indicated better self-reported quality of life, was 36 of a maximum of 52. 3.1. Cost-Effectiveness Results 3.1.1. Propens i ty Score Matching In the absence of randomization, there is no guarantee that the individuals in the extra care housing and care homes admission studies previously described are com- parable. Table 2 presents sample descriptive statistics of the extra care and care home samples before and after matching. We describe the presence of selection bias, i.e. a baseline imbalance between the two groups, by calcu- lating the standardised differences in each baseline vari- able. Differences between the unmatched samples in co- variate means, statistically significant at the 1 percent le- vel, indicated that extra care residents were younger than care home residents and were less likely to have previou- sly lived alone, were less likely to have a longstanding underlying medical condition, were less likely to exhibit problem behaviour, and were less dependent and confu- sed, as measured by the Barthel Index and the MDS CPS scores respectively (Tabl e 2, Columns 1-2 and 5). In or- der to achieve an unbiased comparison of costs, and cost-effectiveness, we controlled for selection bias using the propensity score method described. Figures 1(a) and 1(b) display the overlap between the propensity scores generated by the final logistic model for the probability of being assigned to residential care. Figure 1(a) shows a skewed distribution for the 408 extra care cases compa- red to the slightly more normal distribution of the larger care home group (n = 614). However, after a proportion Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JSSM  Evaluating Extra Care Housing for Older People in England: A Comparative Cost and Outcome Analysis with Residential Care Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JSSM 529 Table 2. Descriptive statistics for overall and matched samples. Baseline characteristics before matching samples Baseline characteristics after matching with 1995 Res. Care Testing difference between Extra Care & 1995 Res. Care groups Variables Extra Care (n = 408) 1995 Res. Care (n = 614) Extra Care (n = 240) 1995 Res. Care (n = 240) Before matching (p-value) After matching (p-value) % bias between groups Age (mean) 76.5 83.3 80.5 82.4 >0.001 0.083 –19.7 Female (proportion) 0.66 0.74 0.69 0.71 0.005 0.485 –6.4 Household composition >0.001 0.423 7.4 Lived Alone 0.57 0.71 0.62 0.70 Married/not alone 0.27 0.15 0.25 0.14 Not lv alone or married 0.15 0.14 0.13 0.16 Relation to head of household 0.237 0.761 2.7 Spouse/ Cohabitating 0.85 0.88 0.86 0.87 Other 0.15 0.12 0.14 0.13 Tenure 0.66 0.779 –2.5 Owner Occ. 0.30 0.29 0.27 0.26 Rented 0.70 0.71 0.73 0.74 Longstanding Illness 0.85 0.93 0.88 0.91 >0.001 0.176 –12.4 Nursing Need 0.18 0.23 0.22 0.21 0.101 0.655 4.1 Freq. problem behaviour >0.001 0.713 3.1 Never/ very unusual 0.94 0.67 0.91 0.92 Sometimes (>weekly) 0.05 0.21 0.08 0.08 Frequently (daily) 0.01 0.12 0.02 0.01 Barthel Index (mean) 14.75 12.77 13.94 13.89 >0.001 0.898 1.1 Mdscps (mean) 0.60 2.39 0.87 0.93 >0.001 0.751 –4.2 Intact 0.70 0.23 0.60 0.53 Borderline intact 0.14 0.13 0.16 0.21 Mild impairment 0.08 0.12 0.10 0.10 Moderate impairment 0.06 0.26 0.10 0.13 Mod severe impairment 0.01 0.07 0.01 0.01 Severe impairment 0.02 0.19 0.03 0.02 Very severe impairment 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 (a) (b) Figure 1. (a) Propensity score overlap before matching. *untreated = Extra Care Resident, treated = 1995 Care Home. (b) Pro- pensity score ove r lap after matching.  Current Distortion Evaluation in Traction 4Q Constant Switching Frequency Converters 530 (39 percent, n = 240) of the care home cases were ma- tched with the majority of extra care cases (60 percent, n = 240), the distribution of the groups was closer (Figure 1(b)), indicating correction of confounded ness. The final sample included 480 cases—evenly matched between ex- tra care and residential care; i.e. 240 matched pairs. The average propensity score of the matched care home group (0.49) differed only slightly from the average propensity score of the extra care group (0.46) as did the minimum and maximum propensity scores (0.009 to 0.95; and 0.009 to 0.94 respectively). The differences in covariate means between the two groups reduced substantially when we matched the individuals according to the set of defined covariates as entered into the logistic regression model in Table 3. The last two columns in Ta ble 2 de- monstrate that balance was achieved in all of the covaria- tes after matching. No statistically significant differences between the matched groups remained. Apart from on the indicator variable of a longstanding underlying medical condition, all differences (i. e. % bias) in terms of needs- related covariates were less than 5 per cent. Simple biva- riate comparisons on a few variables that were not in the model, but that could help suggest possible indicators that were not captured in the propensity score, suggest that the groups are robustly similar. The groups did not differ by relation to head of household or previous tenure. Con- sequently, we are confident that the conclusions with re- gard to the cost-effectiveness of extra care, reported be- low, were not related to differences in the characteristics of the residents in the matched samples. The analyses presented in this paper are based on indi- viduals who were alive and traced at six months when in- dividualised cost and outcome data were collected. How- ever, the extra care evaluation experienced a high drop out of study participants between the interview stages at admission and six months. To investigate attrition bias, we applied the same propensity score approach to match 488 individuals in our extra care housing sample with those in care homes by disregarding whether they had survived to six months. Only a slightly higher proportion of individuals died before the six month interview stage in the care homes sample compared with the extra care group (17 percent compared with 8 percent, respective- ly). However In the extra care group, twenty-eight per cent of the individuals were not traced, or withdrew, be- fore the six month follow-up stage. Those who remained for at least six months, where slightly less cognitively impaired than those who dropped out (average MDS CPS score of 0.82 compared with 1.17 score, respectively) but this difference was significant at only the 10 per cent le- vel. The mean Barthel score was almost identical (13.98 compared with 14.05). Individuals more recently admitted to care homes are more dependent than they were in the 1990s and so the size of the “overlap” group between extra care and care home residents—where the cost effectiveness analysis results are applicable-would be expected to be smaller. Indeed, it is arguable that our matched sample of 1995 care homes residents could all be living in private hou- seholds now. Therefore, we applied the same propensity score approach to a 2005 PSSRU survey of admissions to care homes in 16 local authorities in England, to explore the proportion of the 2005 sample that could be matched to our extra care evaluation dataset. This 2005 study was conducted just a year before our first extra care scheme opened, so is close to contemporaneous. The 2005 data- set consisted of 820 people aged 65 or over. Excluding individuals admitted to nursing beds and the presence of missing data for some covariates employed in predicting propensity scores reduced the available sample to 469 admissions. Subsequently, 30 per cent of these 2005 care home admissions (n = 136) were matched to an extra cent of the 1995 care homes group (n = 240) could be Table 3. Logistic regression model predicting propensity scores: care homes vs. extra. No. obs = 1022 pseudo R2 = 0.44 VariableCoefficient std. error p-value (95% Conf. Interval) Age 0.576 0.058 >0.001 0.463 0.689 Gender, female –0.117 0.192 0.541 –0.494 0.259 Not living alone –0.324 0.121 >0.001 –0.562 –0.086 Longstanding Illness 0.212 0.257 0.409 –0.291 0.715 Nursing Need 0.147 0.207 0.480 –0.260 0.553 Freq. problem behaviour 0.830 0.227 >0.001 0.384 1.275 Barthel Index (less dependent) –0.090 0.019 >0.001 –0.127 –0.053 Mdscps (more impaired) 0.715 0.071 >0.001 0.576 0.853 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JSSM  Evaluating Extra Care Housing for Older People in England: A Comparative Cost and 531 Outcome Analysis with Residential Care matched. Table 4 presents descriptive statistics for the extra care group, the 1995 care home group and the 2005 care home group before and after matching. Table 4 (Co- lumn 9) shows that only in terms of frequency of prob- lem behaviour and physical functioning (as measured by the Barthel Index) are there small statistically significant differences (p = 0.095 and p = 0.025, respectively) be- tween the matched samples extracted from the 1995 and 2005 care home admissions datasets. All of the 136 extra care residents who were matched to a 2005 care home resident were within the group of 240 extra care residents who were matched to a 1995 care home resident. To in- crease the robustness of the results reported in this paper, we therefore conduct two cost-effectiveness analyses: one for 1) all of the 240 matched pairs and another 2) for the sub-set of 136 extra care residents for whom a match could be found in both the 1995 and 2005 care home sa- mples. Table 4 (Column 10) shows that no statistically significant differences remained between the 2005 sub- group of 136 care home individuals and the 1995 sub- group of 136 care home individuals who were matched to the same subgroup of extra care residents. Table 4. Descriptive statistics for overall and matched samples. Column 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Baseline characteristics before matching samples Baseline characteristics after matching with 1995 Care Homes Admissions Baseline characteristics after matching with 2005 Care Homes Admissions Testing difference between the matched samples (p-value) Variables Extra Care (n = 408) 1995 Res. Care (n = 614) 2005 Res. Care (n = 469) Extra care (n = 240) 1995 Res. Care (n = 240) Extra care (n = 136) 2005 Res. Care (n = 136) 1995 Res. Care (n = 136) Columns 5 & 7 Columns 7 & 8 Age (mean) 76.5 83.3 84.7 80.5 82.4 81.2 83.0 84.0 0.473 0.286 Female (proportion) 0.66 0.74 0.73 0.69 0.71 0.66 0.65 0.74 0.208 0.308 Household composition 0.633 0.437 Lived Alone 0.57 0.71 0.79 0.62 0.70 0.59 0.75 0.75 Married/not alone 0.27 0.15 0.11 0.25 0.14 0.29 0.11 0.15 Not lv alone or married 0.15 0.14 0.10 0.13 0.16 0.12 0.14 0.10 Relation to head of household 0.008 0.125 Spouse/ Cohabitating 0.85 0.88 0.74 0.86 0.87 0.87 0.87 0.92 Other 0.15 0.12 0.26 0.14 0.13 0.13 0.12 0.08 Tenure 0.879 0.563 Owner Occ. 0.30 0.29 0.25 0.27 0.26 0.29 0.26 0.28 Rented 0.70 0.71 0.75 0.73 0.74 0.71 0.74 0.72 Longstanding Illness 0.85 0.93 0.94 0.88 0.91 0.91 0.90 0.93 0.524 0.332 Nursing Need 0.18 0.23 0.45 0.22 0.21 0.30 0.28 0.24 0.132 0.116 Problem behaviour 0.095 0.867 Never/very unusual 0.94 0.67 0.62 0.91 0.92 0.88 0.85 0.86 Sometimes (>weekly) 0.05 0.21 0.23 0.08 0.08 0.10 0.13 0.12 Frequently (daily) 0.01 0.12 0.15 0.02 0.01 0.03 0.02 0.02 Barthel Index (mean) 14.75 12.77 9.97 13.94 13.89 12.28 11.97 12.82 0.025 0.146 Mdscps (mean) 0.60 2.39 2.96 0.87 0.93 1.23 1.19 1.31 0.187 0.350 Intact 0.70 0.23 0.15 0.60 0.53 0.49 0.41 0.36 Borderline intact 0.14 0.13 0.10 0.16 0.21 0.16 0.19 0.21 Mild impairment 0.08 0.12 0.12 0.10 0.10 0.13 0.18 0.15 Moderate impairment 0.06 0.26 0.23 0.10 0.13 0.15 0.16 0.21 Mod severe 0.01 0.07 0.13 0.01 0.01 0.01 0.02 0.02 Severe 0.02 0.19 0.25 0.03 0.02 0.06 0.03 0.03 Very severe 0.00 0.00 0.03 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JSSM  Evaluating Extra Care Housing for Older People in England: A Comparative Cost and 532 Outcome Analysis with Residential Care 3.1.2. Cost-E f f ect i venes s Analysis I: (240 Matched Pairs) The mean cost per person per week for the group of 240 extra care cases (i.e. Table 2) was £374 per week at 2008 prices, with a standard deviation of £131 (range £172 to £892; 95% confidence interval £357 to £391). Health ca- re costs are not included in this estimate, for the reasons outlined previously. A break-down of the costs of the com- ponent parts is presented in Table 5; most variability was observed in social care costs (mean £123, range £0 to £612). Detailed service utilisation data for the 240 study members formed the basis of the cost estimates ofhealth and social care. In comparison, the mean weekly cost per care home resident was £409, with a standard deviation of £65 (ran- ge £310 to £610, 95% confidence interval £400 to £417). These estimates are reported in Table 6. Over the six month follow-up period, the average cost saving in fa- vour of extra care housing was £902 (95% confidence interval £421 to £1,383); and this between-group cost difference was statistically significant (t test, p < 0.001). The mean score on the outcome measure, the Barthel Index of ADLs, was practically the same for both groups at baseline (13.94 compared with 13.89 for the care ho- mes group, p = 0.898). At the six month follow-up stage the scores were 14.22 for extra care versus 13.51 for the care homes group. Thus, there had been a marginal im- provement in extra care residents’ abilities (0.28) and a decline amongst those in residential care homes (–0.37). The between group difference for the changes in Bar- thel scores over six months from baseline to the follow- up stage (0.65, standard deviation 0.42) was statistically significant at the 10 percent level (t test, p = 0.07), as shown in Table 6. Normally, a higher score on the Bar- thel indicates greater independence but to simplify inter- pretation (and for consistency with the scoring of the MDS CPS), the scoring was reversed for purposes of cal- culating the cost-effectiveness ratios which follow. Thus, a between-group difference of 0.65 on the Barthel indi- cates that, on average, extra care residents had better out- comes than care home residents over the six months. On the MDS CPS, indicating cognitive functioning, the extra care group remained stable whilst the care homes group showed some slight deterioration. The average incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) is given in Table 6, together with a bootstrapped estimate of standard errors. The point estimate of the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio was –£1,406, i.e. a £1,406 savings for the extra care group over six months per additional point gained on the Barthel Index (mean cost difference –£902 per six months, mean outcome difference 0.65). The mean ICER using the Barthel Index outcome measure would be located in the south-east quadrant of the cost-effectiveness plane: on average, extra care seems to be “dominant”. However, to reflect the uncertainty in the Table 5. Cost estimates for extra care (per week). Cost Component No. Mean Std. Dev Min Max Capital, incl. land 240 106.45 21.26 50.93157.12 Housing management240 53.18 15.25 21.1777.67 Support costs 240 9.81 4.51 2.41 22.14 Activities cost 240 0.68 1.32 0.00 3.52 Social care 240 123.67 120.84 0.00 612.00 Health care 240 72.08 119.29 0.00 634.29 Living expense 240 80.13 3.26 73.8081.80 Unit Cost per week 240 446.01 191.83 175.361241.70 Unit Cost per week, excl. health cost 240 373.93 130.64 172.29891.52 Table 6. Cost effectiveness analysis n = 240 matched pairs. Mean Std. DevRange (min, max)Mean difference Group difference (p-value) Cost PER WEEK (£) Extra Care 374 131 172 892 1995 Care Homes 409 65 310 663 –34.69 >0.001 Cost PER 6 MONTHS (£) Extra Care 9,722 3,397 4,480 23,179 1995 Care Homes 10,624 1,685 8,059 17,239–901.87 >0.001 Effect over 6M Extra Care 0.28 3.27 (Improvement on Barthel) 1995 Care Homes –0.37 4.33 0.64 0.007 Incremental Cost Effectiveness Ratio (ICER) –1,406 32586.62* *bootstrapped standard error. Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JSSM  Evaluating Extra Care Housing for Older People in England: A Comparative Cost and 533 Outcome Analysis with Residential Care estimates of mean costs and effects, Figure 2 presents a scatter plot of the simulated cost-effectiveness ratios, estimated by repeated sampling (1000 times from the same core sample) as part of the bootstrapping exercise. Quadrants to the right of the y-axis represent the region where extra care is associated with a net gain in effect (97 percent). Quadrants below the x-axis represent the region where extra care is associated with a net savings in cost (100%). The distribution of the simulated incre- mental cost effectiveness ratios (ICERs) was thus predo- minantly in the “less costly, more effective” south-east qua- drant. Even allowing for uncertainty, extra care housing appears to be more cost-effective than conventional care home provision for our matched sample (n = 480). 3.1.3. Cost-E F fecti veness Analysis II: (136 Matched Pairs) As discussed, we repeated the cost-effectiveness analysis for the subset of 136 extra care individuals (and their matched counterpart from the 1995 care homes sample), for whom a match was also found in the 2005 care homes dataset. Table 7 shows that the cost of extra care per person per week increased from £374 to £403 and the cost for the care homes group increased from £409 to £413. The incremental cost-effectiveness ratio, however, decreased to a savings of £330 for the extra care group over six months per incremental improvement in the Bar- thel Index score (mean between-group cost difference –£252 per 6 months, mean outcome difference 0.76), as shown in Table 7. The associated scatter plot (Figure 3) indicates that extra care appears more effective than re- sidential care at approximately an equivalent cost (although the scatter of points indicates that this result is less cer- tain than the results for the larger sample in Figure 2). The wide dispersion of points above and below the hori- zontal x-axis indicates that there is uncertainty about whether this apparent gain in outcomes is achieved at a lower or higher cost. As shown in Table 7, between- group differences were not statistically significant. Using the bootstrapped data presented in Figure 3 al- lowed us to plot the cost-effectiveness acceptability cur- ve [72,74,5,]. The solid line in Figure 4 shows the pro- bability that extra care is cost-effective for a range of va- lues for the decision-makers’ willingness to pay (λ) for an additional point improvement on the Barthel Index of Ac- tivities of Daily Living. The curve demonstrates that the probability of extra care being more cost-effective than residential care is 76 per cent. If decision-makers’ willing- ness to pay (λ) was £400 per point improvement on the Barthel Index over six months, then the probability of extra care being cost-effective increases to 90 per cent. The de- velopment of cost-effectiveness acceptability curves re- minds us that the absence of a statistical differrence (in ei- ther costs or effects) does not necessarily mean that the two treatments cannot in fact be distinguished [70]. 4. Discussion The evaluation reported on here, the first large scale eva- luation of extra care housing funded by the Department of Health in England, focused on schemes that were develo- ped in response to a specific government capital grant pro- gramme. While this focus means the schemes may not ne- cessarily be representative of the wider extra care market in England with providers across the not-for-profit and private sectors, this study adds significantly to the evidence base on the cost implications of extra care housing. Particularly in the current financial climate, information about the com- parative costs and benefits of alternative courses of action are needed to target resources effectively. Figure 2. CE-plane, n = 240 matched pair s. Table 7. Cost effectiveness analysis n = 136 matched pairs. MeanStd. DevRange (min, max) Mean difference Group difference (p-value) Cost PER WEEK (£) Extra Care 403 138 172 892 1995 Care Homes 413 66 310 663 –9.68 0.484 Cost PER 6 MONTHS (£) Extra Care 10,4783,597 4,480 23,179 1995 Care Homes 10,7301,716 8,059 17,239 –251.68 0.484 Effect over 6M Extra Care 0.72 3.54 (Improvement on Barthel) 1995 Care Homes –0.04 4.33 0.76 0.131 Incremental Cost Effectiveness Ratio (ICER) –329 3325.71* *bootstrapped standard error Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JSSM  Current Distortion Evaluation in Traction 4Q Constant Switching Frequency Converters 534 Figure 3. CE-plane, n = 136 matched pair s. Figure 4. CE-acceptability curve. The study demonstrated that extra care has benefits for physical functioning when compared with residential ca- re, and that the associated costs were lower, to a statistic- cally significant degree. On average, an incremental im- provement in outcome cost £1406 less for the extra care group over a six month period. The same was true for the secondary analysis of cost-effectiveness, conducted to a- ddress the expectation of likely higher levels of depen- dency of publicly-funded people moving into care homes since 1995. Based on matched samples with baseline de- mographics equivalent to 30 percent (n = 136) of the 2005 PSSRU care homes admission study, the cost of achie- ving an incremental improvement in the Barthel Index during six months was £330 less in extra care than in residential care. Because of the uncertainty and the need to cast these findings in a decision-making framework, we plotted cost-effectiveness planes and an acceptability curve. Under reasonable assumptions there appears to be a high probability that extra care is more cost-effective than residential care. Yet, it should be noted that we are not aware of evidence on societies’ or social care system decision makers’ (or indeed residents’) actual willingness to pay for such physical functioning improvements. When we matched our sample with people who moved into care homes in 1995, and the type of people who mo- ved in in 2005, our analyses suggested better outcomes in terms of functional and cognitive ability at six months in extra care housing. Although it is difficult to identify prevention, as by definition we cannot observe what does not happen, we would expect this finding to have benefi- cial implications for people’s future needs for care and support services. Indeed, an in-depth study of the costs before and after individuals from the community moved into one of the extra care schemes in our sample sugge- sted that by maintaining residents’ functional abilities, hospital admissions and crisis demands for health servi- ces may have been avoided in that higher social care co- sts were associated with lower health care costs [76]. Fur- thermore, while our cost effectiveness analyses focused on changes in functional ability, ultimately the objective is improved quality of life. By restricting the domain of “effectiveness” to functional outcomes, the analysis un- derestimates the benefits of 1) formal care provision (which reduces informal carer burden) and 2) the living environment. First, results from an in-depth study of the costs before and after individuals from the community moved into one of the schemes in the extra care evalua- tion suggest that informal care costs are low in extra care housing [76,77]. The issue of apportioning costs for info- rmal carer burden would need to be considered if the comparison group in the cost-effectiveness analysis is people living in their own homes: the aforementioned study [76,77] identified an average 30 per cent reduction in informal care costs after the move. Second, the nature of extra care, where people have their own front door wi- th 24 hour care and support available, is personalised, and has consistently been shown to deliver high levels of social well-being and friendship formation [10,11] An analysis of cost variation between extra care schemes [49] showed that at an individual level, higher costs were as- sociated with greater well-being (as measured by CASP- 19 well-being scale [73]) once people’s levels of func- tioning were allowed for. Taking into consideration the wi- der range of benefits to extra care residents, including the impacts on national objectives such as well-being, choice and independence, would further strengthen value for money judgements about extra care housing. The lower cost-effectiveness ratio obtained in the se- cond cost-effectiveness analysis was predominantly due to a smaller between-group cost difference rather than to a greater difference in the outcome measurement on the Barthel Index. The mean cost savings associated with ex- tra care was only £252 over six months, compared with £902 previously. The reduction in between-group cost di- fference was driven entirely by statistically significant hi- gher costs for social care services for the extra care group Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JSSM  Evaluating Extra Care Housing for Older People in England: A Comparative Cost and 535 Outcome Analysis with Residential Care comprising a slightly higher needs subset of the original matched extra care sample (£35 more costly per week, p = 0.002). This is not entirely unexpected. Higher needs individuals can represent a population with a greater cost and outcome interaction (i.e. improvement in outcome is associated with greater resource use, hence cost). A que- stion that arises is the extent to which extra care can easi- ly support people with more severe problems [7,14,78], and behind this question are fundamental questions rele- vant to the extra care workforce in terms of its profile; composition; activities; effectiveness and significantly, its labour cost [79]. Whereas residential care is purchased for a fixed fee (or range of fixed fees), extra care housing will become increasingly expensive to social care funders above a certain needs threshold, i.e. as costs rise with in- creased care need. A study on the cost variation between extra care sche- mes confirmed the strong influence on cost of residents’ levels of physical and cognitive functioning, and espe- cially the need for nursing type care [49]. The schemes in the present study aimed for, and for the most part achie- ved, a balance of residents with high, medium and low care needs-although the interpretations of these catego- ries can vary considerably [80]. However, inevitably, su- ch balanced communities within schemes will be affected by residents’ changing needs over time and maintaining the balance appears to be difficult [7]. Furthermore, hou- sing providers face considerable pressure from local au- thorities to increase the number of residents with higher care needs, and some have agreed to do this [14,80]. However, other studies have suggested that extra care can- not easily support people with more severe problems [7, 78], and have reported that some residents who develo- ped severe behavioural problems had to move on to other settings [81]. If a pattern of rising need levels in the extra care housing sector does develop, the financial implica- tions on unit costs could be substantial, as the package costs of individuals (the cost of the combination of ser- vices they use) would be higher with increased depen- dency. Yet, it should be noted, that this would still not in- crease the unit cost in the way that care homes costs do. Another consequence of an increase in the proportion of people with higher needs may be a restricted source of informal support. A less balanced mix of residents may hinder the development of a vibrant community where more active residents provide a source of support [11], and, in the present study, individuals who were more de- pendent also tended to live alone. An important aspect of both overall costs and incen- tives for investment is that, while we have focused here on the comparison with residential care, a substantial pro- portion of people who live in extra care schemes are more able, and it is this element of a balanced commu- nity, including the active involvement of residents in the schemes, that contributes to their success. With the ex- ception of the more able people in the villages, residents still have higher needs for help than in the general popu- lation. It was not possible in this study to compare out- comes for those that would otherwise have remained in their previous homes in the community. With pressures on councils to increase eligibility criteria for social care re- ceipt, the chances are high that the true alternative would be a lack of any wholly publicly-funded support for most. Increasing provision for such individuals, therefore, req- uires improved strategic planning by social services de- partments and their planning, health and housing partners to facilitate the market development of a range of hous- ing with care solutions locally, including extra care. A cost effective alternative to care homes which is po- sitively regarded by older people is clearly very welcome. However, a major barrier to a shift towards extra care housing is the relatively low level of current provision. Using a broad definition, there were about 43,300 extra care units of accommodation in England in 2009 [82] and nearly 480,000 units of ordinary sheltered housing [83], compared with about 276,000 residential care places and about 179,000 nursing care places in care homes in the United Kingdom [55]. In a climate of financial austerity, investment in such provision seems unlikely if decision makers are focused on immediate rather than longer term cost savings. Even within the course of the study, the do- wnturn in the property market suggested that private in- vestment and willingness of individuals to purchase extra care property was not looking promising. Moreover, the complexities of the funding arrangements in extra care housing are such that no one sector will both bear the costs and reap the benefits. In such situations we can ex- pect individual sector perspectives to drive decision-ma- king rather than the overall public good. An in-depth stu- dy of one of the 19 schemes in our evaluation showed that in that instance the public purse bore the vast majori- ty of the cost [76,77]. This is not surprising however, as we would expect the allocation of costs for the 19 sche- mes in the extra care evaluation to reflect the fact that they were partially funded under the Department of Hea- lth Extra Care Housing Fund, which was encouraging innovation. Whatever the pattern for the schemes at the time of the evaluation, this is likely to change in the fu- ture, with changes in the basis for long-term care funding [84]. One important implication of this study is that in any future recommendations we would hope to see in- centives in place that encourage this type of provision. 5. Conclusions This study marks a significant improvement in the evi- Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JSSM  Evaluating Extra Care Housing for Older People in England: A Comparative Cost and 536 Outcome Analysis with Residential Care dence base on extra care housing in England. Extra care housing is clearly an important innovation in the care and support of older people in England and one that has con- siderable potential to support older people in leading ac- tive, engaged lives. Factors encouraging the development of extra care schemes include the ageing of the popula- tion, the policy endorsement of “ageing in place”, the de- velopment of new lifestyles in later life, and the wide re- cognition of the need for greater choice and flexibility in housing options for older people [25,85]. The generally very positive experience that extra care residents report [10,11,78,86] suggests that this is indeed a promising ty- pe of provision. This positive picture raises the issue of cost. For improved productivity we want both better out- comes and either the same or, ideally, lower costs. This study found that costs were lower when comparing equi- valent people who moved into publicly-funded residen- tial care homes in 1995, and similar to the more depen- dent type of person moving into care homes in 2005. Si- milar or lower costs combined with better outcomes mean that although extra care housing does not appear to pro- vide a direct alternative, it can support some older people at risk of moving into a residential care homes in a cost- effective way. Necessarily this type of research serves to highlight unanswered questions which would warrant fur- ther research. If extra care housing is to be used as an alternative to residential care, further work is needed on how best to support those who are more dependent with more severe problems. Further work is also needed on the cost and outcome implications for more able indi- viduals; it was not possible in this study to compare out- comes for those who would otherwise have remained in their previous homes in the community. 5. Acknowledgements This research study was funded by the Department of Health and was conducted as part of the PSSRU Housing and Care Programme. We would like to thank Jeremy Porteus at the Department of Health and the members of the Steering Group for their guidance; the Housing Lea- rning and Improvement Network (funded by the Depart- ment of Health); our social services liaison contacts; the Registered Social Landlords (housing associations); the staff of the schemes; and, particularly, the residents who gave up their time to be interviewed for the project and shared their personal views and experiences with us so o- penly and honestly. Lesley Cox and Jane Dennett undert- ook the data preparation work at the PSSRU. The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and are not necessarily those of the Department of Health. REFERENCES [1] Department for Communities and Local Government, “Lifetime Homes, Lifetime Neighbourhoods. A national strategy for housing in an ageing society”, Department for Communities and Local Government, London, 2008. [2] Department of Health, “A Vision for Adult Social Care: Capable Communities and Active Citizens,” Department of Health, London, 2010. [3] Department of Health, “Government Announces Funding for Extra Care Housing, Press Release 2003/0248,” De- partment of Health, London, 2003. [4] Department of Health, “Independence, Well Being and Choice: Our Vision for the Future of Social Care for Adults in England (Cm 6499),” The Stationery Office for the Department of Health, London, 2005. [5] Laing and Buisson, “Extra-Care Housing UK Market Re- port 2010,” 10th Edition, Laing and Buisson, London, 2010. [6] S. Evans, “Community and Ageing-Maintaining Quality of Life in Housing with Care Settings,” Policy Press, Bristol, 2009. [7] K. Croucher, L. Hicks and K. Jackson, “Housing with Ca- re for Later Life: A Literature Review,” Joseph Rowntree Foundation, York, 2006. [8] F. Wright, A. Tinker, J. Hanson, H. Wojgani and R. Ma- yagoitia, “Some Social Consequences of Remodelling English Sheltered Housing and Care Homes to Extra Care,” Ageing and Society, Vol. 29, No. 1, 2009, pp. 135-153. doi:10.1017/S0144686X08007630 [9] T. Bäumker, L. Callaghan, R. Darton, J. Holder, A. Net- ten and A. Towers, “Deciding to Move into Extra Care Housing: Residents’ Views,” Ageing & Society, 2011, Vol. forthcoming. [10] S. Evans and S. Vallelly, “Social Well-Being in Extra Ca- re Housing,” Joseph Rowntree Foundation, York, 2007. [11] L. Callaghan, A. Netten and R. Darton, “The Develop- ment of Social Well-Being in New Extra Care Housing Schemes,” Joseph Rowntree Foundation, York, 2009. [12] Department of Health, “Extra Care Housing for Older Pe- ople: An Introduction for Commissioners,” Department of Health, London, 2003. [13] T. Bäumker, R. Darton, A. Netten and J. Holder, “The Development Costs and Funding of Extra Care Housing,” Public Money and Management, Vol. 31, No. 6, 2011, p. 31. [14] R. Darton, T. Bäumker, L. Callaghan, J. Holder, A. Ne- tten and A. Towers, “The Characteristics of Residents in Extra Care Housing and Care Homes in England,” Health and Social Care in the Community, Vol. forthcoming, 2011. [15] F. Wright, “Review: Housing with Care for Later Life: A Literature Review,” Ageing & Society, Vol. 27, No. 1, 2007, pp. 165-174. [16] S. Winters, “Lifetime Housing in Europe,” Proceedings of the European Seminar and Colloquium, Living Tomo- rrow Starts Today, 4-5 December 2000, Hoger Instituut Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JSSM  Evaluating Extra Care Housing for Older People in England: A Comparative Cost and 537 Outcome Analysis with Residential Care voor de Arbeid, Leuven, 2001. [17] M. E. Hunt, A. Feldt, R. W. Marans, L. Pastalan and K. Vakalo, “Retirement Communities: An American Origi- nal,” The Haworth Press, New York, 1984. [18] J. Citro and S. Hermanson, “Assisted Living in the United States,” American Association of Retired Persons, Public Policy Institute, Washington (DC), 1999. [19] J. Frank, “How Long Can I Stay? The Dilemma of Aging in Place in Assisted Living,” Journal of Housing for the Elderly, Vol. 15, No. 1/2, 2001, pp. 5-30. doi:10.1300/J081v15n01_02 [20] S. Sherwood, H. S. Ruchling, C. C. Sherwood and S. A. Morris, “Continuing Care Retirement Communities,” Jo- hns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore (MD) and Lon- don, 1997. [21] C. Hawes, C. D. Phillips, M. Rose, S. Holan and M. She- rman, “A National Survey of Assisted Living Facilities,” The Gerontologist, Vol. 43, No. 6, 2003, pp. 875-882. doi:10.1093/geront/43.6.875 [22] V. Regnier, “Design for Assisted Living: Guidelines for Housing the Physically and Mentally Frail,” John Wiley & Sons, New York, 2002. [23] D. A. Wolf and C. Jenkins, “Family Care and Assisted Living: An Uncertain Future?” In: S. M., G. and J. Hyde, Eds., The Assisted Living Residence: A Vision for the Future, The Johns Hopkins University Pres, Baltimore (MD), 2008, pp. 198-222. [24] J. Pynoos and P. S. Liebig, “Housing Frail Elders: Inter- national Policies, Perspectives, and Prospects,” The Johns Hopkins University Press Baltimore (MD) and London, 1995. [25] F. Heywood, C. Oldman and R. Means, “Housing and Home in Later Life,” Open University Press, Buckingham, 2002. [26] N. Appleton and M. Shreeve, “Now for Something Dif- ferent: The Extra Care Charitable Trust’s Approach to Retirement Living”, Old Chapel Publishing, Witney, 2003. [27] Housing Learning and Improvement Network, “Extra Ca- re Strategic Developments in North Yorkshire (Case Study No. 1),” Housing Learning and Improvement Net- work, Department of Health, London, 2003. [28] Department of Health, “New Report Shows that Stan- dards of Care for Older People in Homes are Improving,” Department of Health, London, 2004. [29] Office for National Statistics, “Ageing and Mortality in the UK: National Statistician’s Annual Article on the Po- pulation,” Office of National Statistics, London, 2008. [30] K. Lisenkova, R. W. McQuaid and R. E. Wright, “Intro- duction to the Economics of an Ageing World,” Journal of the Academy of Social Sciences, Vol. 5, No. 3, 2010, pp. 229-231. [31] T. Brown, “Housing an Ageing Population: The Extra Care Solution,” Keep Moat and Housing Learning and Improvement Network, London, 2011. [32] P. Fletcher, M. Riseborough, J. Humphries, C. Jenkins and P. Whittingham, “Citizenship and Services in Older Age: The Strategic Role of Very Sheltered Housing,” Housing 21, Beaconsfield, 1999. [33] Laing and Buisson, “Extra-Care Housing UK Market Re- port 2009,” 9th Edition, Laing and Buisson, London, 2009. [34] C. Oldman, “Blurring the Boundaries: A Fresh Look at Housing and Care Provision for Older People,” 2000 Edi- tion, Joseph Rowntree Foundation & Pavilion Publishing Ltd., Brighton, 2000. [35] T. Baker, “An Evaluation of an Extra Care Scheme—Ru- nnymede Court, Estover, Plymouth,” Hanover Housing Association, Staines, 2002. [36] J. Bartholomeou, “A View of the Future—The Experi- ence of Living in Extra Care,” Hanover Housing Group, Staines, 1999. [37] A. Bailey, “Making God Wait: An Alternative to Resi- dential Care,” Housing, Care and Support, Vol. 1, No. 2, 1998, pp. 21-24. doi:10.1108/14608790199800019 [38] Royal Commission on Long Term Care, “With Respect to Old Age: Long Term Care—Rights and Responsibilities: A Report by the Royal Commission on Long Term Care, (Chairman: Professor Sir Stewart Sutherland). Research Volume 2: Alternative Models of Care for Older People,” The Stationery Office, London, 1999. [39] R. Darton, T. Bäumker, L. Callaghan and A. Netten, “The PSSRU Evaluation of the Extra Care Housing Initiative: Technical Report,” Personal Social Services Research Unit, University of Kent, Canterbury, 2011. [40] A. Bebbington, R. Darton and A. Netten, “Care Homes for Older People: Volume 2. Admissions, Needs and Outcomes. The 1995/96 National Longitudinal Survey of Publicly-Funded Admissions,” Personal Social Services Research Unit, University of Kent at Canterbury, 2001. [41] A. Netten, A. Bebbington, R. Darton and J. Forder, “Care Homes for Older People: Volume 1. Facilities, Residents and Costs,” Personal Social Services Research Unit, University of Kent at Canterbury, 2001. [42] A. Netten, R. Darton, A. Bebbington and P. Brown, “Re- sidential or Nursing Home Care? The Appropriateness of Placement Decisions,” Ageing and Society, Vol. 21, No. Part 1, 2001, pp. 3-23. [43] R. Darton, J. Forder, A. Bebbington, A. Netten, A. M. Towers and J. Williams, “Analysis to Support the Deve- lopment of the Relative Needs Formula for Older People: Final Report,” Personal Social Services Research Unity, University of Kent at Canterbury, 2006. [44] R. Darton, J. Forder, A. Netten, A. Bebbington, J. Holder, and A. M. Towers, “Slicing up the Pie: Allocation of Central Government Funding of Care of Older People,” Social Policy and Administration, Vol. 44, No. 5, 2010, pp. 529- 553. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9515.2010.00728.x [45] J. Forder and A. Netten, “The Price of Placements in Re- sidential and Nursing Home Care: The Effects of Con- Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JSSM  Evaluating Extra Care Housing for Older People in England: A Comparative Cost and 538 Outcome Analysis with Residential Care tracts and Competition,” Health Economics, Vol. 9, No. 7, 2000, pp. 643-657. doi:10.1002/1099-1050(200010)9:7<643::AID-HEC528> 3.0.CO;2-X [46] J. Beecham, “Collecting and Estimating Costs,” In: M. R. J. Knapp, Ed., The Economic Evaluation of Mental Health Care, Arena, Aldershot, 1995, pp. 61-82. [47] M. R. J. Knapp, “The Principles of Applied Cost Re- search,” In: A. Netten and J. M. Beecham, Eds., Costing Community Care: Theory and Practice, Ashgate, Alder- shot, 1993. [48] J. Beecham, “Unit Costs—Not Exactly Child’s Play,” A Guide to Estimating Unit Costs for Children’s Social Care, Department of Health, Dartington Social Research Unit and Personal Social Services Research Unit at the University of Kent, London, 2000. [49] T. Bäumker, A. Netten and R. Darton, “The Costs and Sources of Cost Variation in Extra Care Housing,” Per- sonal Social Services Research Unit, University of Kent, Canterbury, 2011. [50] T. Bäumker and A. Netten, “Costing Extra Care Hous- ing,” In: L. Curtis, Ed., Unit Costs of Health and Social Care 2011, Personal Social Services Research Unit, Can- terbury, Forthcoming. [51] A. Netten, “New Developments and Changes in Guidance on the Discount Rate,” In: A. Netten and L. Curtis, Eds., Unit Costs of Health and Social Care 2003, Personal So- cial Services Research Unit, University of Kent, Canter- bury, 2003. [52] Building Cost Information Service, “Indices and Fore- casts,” BCIS, Royal Institute of Chartered Surveyors, Kingston-upon-Thames, 2008. [53] L. Curtis, “Unit Costs of Health and Social Care”, Per- sonal Social Services Research Unit, University of Kent, Canterbury, 2008. [54] Department of Health, “National Schedule of Reference Costs 1998-2008,” The Stationary Office, London, 2008. [55] Laing and Buisson, “Care of Elderly People UK Market Survey 2009,” 22nd Edition, Laing and Buisson, London, 2009. [56] F. I. Mahoney and D. W. Barthel, “Functional Evaluation: The Barthel Index,” Maryland State Medical Journal, Vol. 14, No. 2, 1965, pp. 61-65. [57] J. N. Morris, B. E. Fries, D. Mehr, C. Hawes, C. Phillips, V. Mor and L. A. Lipsitz, “MDS Cognitive Performance Scale,” Journal of Gerontology: Medical Sciences, Vol. 49, No. 4, 1994, pp. M174-M182. [58] R. B. D’Agostino, “Propensity Score Methods for Bias Reduction in the Comparison of a Treatment to a Non-Randomized Control Group,” Statistics in Medicine, Vol. 17, No. 19, 1998, pp. 2265-2281. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0258(19981015)17:19<2265::AI D-SIM918>3.0.CO;2-B [59] S. Guo, R. P. Barth and C. Gibbons, “Propensity Score Matching Strategies for Evaluating Substance Abuse Ser- vices for Child Welfare Clients,” Children and Youth Ser- vices Review, Vol. 28, No. 4, 2006, pp. 357-383. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2005.04.012 [60] P. R. Rosenbaum and D. B. Rubin, “The Central Role of the Propensity Score in Observational Studies for Causal Effects,” Biometrika, Vol. 70, No. 1, 1983, pp. 41-55. doi:10.1093/biomet/70.1.41 [61] A. Basu, J. Heckman, S. Navarro-Lozano and S. Urzua, “Use of Instrumental Variables in the Presence of Hetero- geneity and Self-Selection: An Application to Treatments of Breast Cancer Patients,” Health Economics, Vol. 16, No. 11, 2007, pp. 1153-1157. doi:10.1002/hec.1291 [62] A. Basu, D. Polsky and W. Manning, “Use of Propensity Scores in Non-Linear Response Models: The Case for Health Care Expenditures,” National Bureau of Economic Research, New York, 2008. [63] A. M. Jones, “Identification of Treatment Effects in Health Economics,” Health Economics, 2007, Vol. 16, No. 11, pp. 1127-1131. doi:10.1002/hec.1302 [64] D. B. Rubin, “Matched Sampling for Causal Effects,” Cambridge University Press, New York, 2006. [65] I. Yanovitsky, E. Zanutto and R. Hornik, “Estimating Causal Effects of Public Health Education Campaigns Using Propensity Score Methodology,” Evaluation and Program Planning, Vol. 28, 2005, pp. 209-220. doi:10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2005.01.004 [66] P. C. Austin, “A Critical Appraisal of Propensity-Score Matching in the Medical Literature between 1996 and 2003,” Statistics in Medicine, Vol. 27, No. 12, 2008, pp. 2037-2049. doi:10.1002/sim.3150 [67] J. A. Smith and P. E. Todd, “Does Matching Overcome LaLonde’s Critique of Non Experimental Estimators?” Journal of Econometrics, Vol. 125, No. 1-2, 2005, pp. 305-353. [68] P. R. Rosenbaum and D. B. Rubin, “Constructing a Con- trol Group Using Multivariate Matched Sampling Metho- ds That Incorporate the Propensity Score,” The American Statistician, Vol. 39, No. 1, 1985, pp. 33-38. doi:10.2307/2683903 [69] J. Dowie, “Why Cost-Effectiveness Should Trump (clinical) Effectiveness: The Ethical Economics of the South West Quadrant,” Health Economics, Vol. 13, No. 5, 2004, pp. 453-459. doi:10.1002/hec.861 [70] M. Knapp, “Cognitive Stimulation Therapy for People with Dementia: Cost-Effectiveness Analysis,” The British Journal of Psychiatry, Vol. 188, No. 6, 2006, pp. 574-574. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.105.010561 [71] J. S. Hoch, A.H. Briggs and A. R. Willan, “Something Old, Something New, Something Borrowed, Something Blue: A Framework for the Marriage of Health Econo- metrics and Cost-Effectiveness Analysis,” Health Eco- nomics, Vol. 11, No. 5, 2002, pp. 415-430. doi:10.1002/hec.678 Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JSSM  Evaluating Extra Care Housing for Older People in England: A Comparative Cost and Outcome Analysis with Residential Care Copyright © 2011 SciRes. JSSM 539 [72] B. van Hout, M. J. Al, G. S. Gorden and F. F. Rutten, “Costs, Effects and C/E-Ratios Alongside a Clinical Trial,” Health Economics, Vol. 3, No. 5, 1994, pp. 309- 319. doi:10.1002/hec.4730030505 [73] M. Hyde, R. D. Wiggins, P. Higgs and D. B. Blane, “A Measure of Quality of Life in Early Old Age: The Theory, Development and Properties of a Needs Satisfaction Model (CASP-19),” Aging and Mental Health, Vol. 73, No. 3, 2003, pp. 186-194. doi:10.1080/1360786031000101157 [74] E. Fenwick and S. Byford, “A Guide to Cost-Effective- ness Acceptability Curves,” The British Journal of Psy- chiatry, Vol. 187, No. 2, 2005, pp. 106-108. doi:10.1192/bjp.187.2.106 [75] E. Fenwick, B. J. O’Brien and A. Briggs, “Cost-Effec- tiveness Acceptability Curves—Facts, Fallacies and Fre- quently Asked Questions,” Health Economics, Vol. 13, No. 5, 2004, pp. 405-415. doi:10.1002/hec.903 [76] T. Bäumker, A. Netten and R. Darton, “Costs and Out- comes of an Extra Care Housing Scheme in England,” Journal of Housing for the Elderly, Vol. 24, No. 2, 2010, pp. 151-170. doi:10.1080/02763891003757098 [77] T. Bäumker, A. Netten and R. Darton, “Costs and Ou- tomes of an Extra-Care Housing Scheme in Bradford,” Joseph Rowntree Foundation, York, 2008. [78] K. Croucher, L. Hicks, M. Bevan and D. Sanderson, “Comparative Evaluation of Models of Housing with Care for Later Life,” Joseph Rowntree Foundation, York, 2007. [79] J. Manthorpe and J. Moriarty, “Housing or Care Workers? Who is Supporting Older People with High Support Needs?” Journal of Integrated Care, Vol. 19, No. 1, 2011, pp. 16-25. doi:10.5042/jic.2011.0032 [80] W. Murphy and L. Miller, “Nomination Arrangements in Extra Care Housing: Factsheet No. 25,” Housing Learn- ing and Improvement Network, Department of Health, London, 2008. [81] S. Vallelly, S. Evans, T. Fear and R. Means, “Opening Doors to Independence: A Longitudinal Study Exploring the Contribution of Extra Care Housing to the Care and Support of Older People with Dementia,” Housing 21, London, 2006. [82] Elderly Accommodation Counsel, “Statistics on Special- ist Housing Provision for Older People in England 2009,” Elderly Accommodation Counsel, London, 2009. [83] Homes and Communities Agency, “Housing Our Ageing Population: Panel for Innovation (HAPPI),” Homes and Communities Agency, London, 2009. [84] Dilnot Commission Report, “Dilnott Commission Report: Commission on Funding of Care and Support,” Depart- ment of Health, London, 2011. http://www.dilnotcommission.dh.gov.uk [85] S. Evans, “That Lot Up There and Us Down Here: Social Interaction and a Sense of Community in a Mixed Tenure UK Retirement Village,” Ageing and Society, Vol. 29, No. 2, 2009, pp. 199-216. doi:10.1017/S0144686X08007678 [86] M. Bernard, B. Bartlam, J. Sim and S. Biggs, “Housing and Care for Older People: Life in an English Pur- pose-Built Retirement Village,” Ageing & Society, Vol. 27, No. 4, 2007, pp. 555-578. doi:10.1017/S0144686X07005983