Technology and Investment

Vol.1 No.3(2010), Article ID:2500,7 pages DOI:10.4236/ti.2010.13027

Do Regional Investment Grants Improve Firm Performance? Evidence from Sweden

1Ministry of Finance, Stockholm, Sweden

2The Ratio Institute, Stockholm, Sweden

3University of Bergen, Bergen, Norway

4Dalarna University, Borlänge, Sweden

5The Swedish Retail Institute, Stockholm, Sweden

E-mail: nru@du.se

Received April 14, 2010; revised July 10, 2010; accepted July 13, 2010

Keywords: Economic Efficiency, Propensity Score Matching, Sample Selection, Logit Regression, Panel Data

Abstract

The effect of Swedish regional investment grants during 1990-1999 on firm performance, in terms of returns on equity and number of employees, were studied using a propensity-score matching-method to control for sample selection. Firms that received grants did not perform better in terms of returns on equity when compared to matched firms in the control group. In most years, recipient firms also did not hire more employees. The results thus cast doubt on the use of regional investment grants as a general policy instrument to improve firm performance.

1. Introduction

Regional investment grants (RIG) distributed directly to firms are common in most industrialized countries around the world. Their goals are different, sometimes being focused on promoting economic growth in the region, other times more oriented towards alleviating the impact of structural changes in the economy. In either case, their existence is based on the assumption that they improve performance of the firms to which they are directed.

A few empirical studies have investigated whether RIG actually influence firm performance. Wren [1] found that Regional Selective Assistance (RSA) in the UK had been successful in promoting new jobs, and thus supporting its expansion. Harris [2] found that Selective Financial Assistance (SFA) in Northern Ireland contributed to more jobs and investments in the region, while Harris and Trainor [3] found that total factor productivity would have been 7-10% lower if the Northern Ireland firms had not received SFA. Harris and Trainor [4] also found that SFA reduced the probability of plant closure by 15-24%. More supportive evidence was presented by [5], who found that Greek capital subsidies targeted at food and beverage manufacturing firms contributed to higher total factor productivity.

On the other hand, Harris and Robinson [6] found that RSA in the UK had no effect on productivity when targeted plants where compared to other plants within the assisted area. Similarly, Bergström [7] found no effect of capital subsidies on total factor productivity in Sweden, while Lee [8] found that industrial targeting in Korea actually lowered total factor productivity of the targeted firms. Thus, the evidence on whether RIG improve firm performance is mixed and inconclusive.

The purpose of this paper is to study whether regional investment grants to firms in Sweden during 1990-1999 had a positive impact on firm performance, indicated by more employees and higher returns on equity. If RIG were successful, we expect that firms receiving grants will have raised employment and returns more than has a control group of firms with similar characteristics.

The analysis is based on comprehensive panel-data set covering all limited firms in Sweden during the study period. From this dataset a sub-sample of firms from the two support areas were selected, thus guaranteeing that firms receiving the grant were not compared to firms from other parts of Sweden. There were considerable differences, on average, between firms that received RIG and the other firms, differences that were controlled for in the analysis using a propensity-score matchingmethod developed by [9]. Propensity-score matching makes it possible to compare firms that had or had not received RIG but are similar in all other relevant aspects. To our knowledge this method has not been previously applied to RIG.

We find that firms receiving RIG did not have better development of returns on equity than others that did not receive grants. In addition, in most cases, RIG did not influence employment either. The exceptions were in 1994 and 1995, during the last years of the 1990 recession. Thus, our results cast doubt on the general efficiency of RIG in promoting firm performance.

The next section describes the RIG in Sweden, while Section 3 presents the data and the method of propensityscore matching as well as discussing the differencein-difference estimation procedure. Results are then presented and discussed in Section 4, while Section 5 details our conclusions.

2. Regional Grants in Sweden

In Sweden, regional investment grants directly to firms go back to the 1960s, when firms were given grants if they made new investments in outlying regions with free capacity. RIG became even more common during the 1970s and more oriented towards reducing distributional differences across regions. However, from 1990 onwards, grants have been targeted more towards promoting economic growth. Grants are limited to firms that have a market outside their own county or that face competition from outside the county. Firms are not given grants that it is believed might undermine local competition.

In order to receive RIG, the firm must apply in writing to the County Administration Board (Länsstyrelsen) or the Swedish Agency for Economic and Regional Growth (NUTEK), including a business plan and a description of the expected results. A processing officer decides whether the application is entitled of receiving support, taking into account the economic situation of the firm. For example, firms with lower probability of receiving financial support from commercial banks are more likely to receive grants so that high-risk projects are overrepresented. It is also evaluated whether the firm can expand and survive in the future, and any complaints to the Swedish Enforcement Authority (Kronofogden) are taken into account. Small firms and investments expected to increase integration and equality in society are also given priority.

Grants can be given for investment in machinery, buildings, inventory, patents, and licenses. In exceptional cases, grants can also be given for investment in education, consulting, participating in conferences, and research and development. Depending on the region, grants can cover at most 20-30% of the total investment cost.

RIG constitute the largest regional policy-instrument directed towards promoting firm performance in Sweden. Thus, this paper focuses on them, and excludes other grants from the empirical analysis. However, during the study period there were a number of other regional grants in Sweden, e.g., countryside-support grants, employment grants, transportation grants, and small-firm investment grants, which will also be described briefly.

Countryside-support grants, also issued by the County Administrative Board (Länsstyrelserna), aimed to contribute to sustainable rural growth in rural areas in Sweden by ensuring a minimum of commercial services. Municipalities, retail stores, and gas stations were typical recipients.

To promote growth and create new rural employment opportunities, there were two types of employment grants given to firms when they recruited new employees, or when they entered new local markets—again issued by the County Administrative Board (Länsstyrelserna), or the Swedish Agency for Economic and Regional Growth (NUTEK), or the Swedish national government itself.

Transportation grants were also available to manufacturing firms in the four most northern municipalities in Sweden to compensate them for higher transportation costs. Finally, small-firm investment grants (SFG) were available to firms with less than 50 employees but yearly revenues of more than seven million Euro.

3. Empirical Method

3.1. Data

In order to study whether regional investment grants for firms have any impact on firm performance, we need both firm-specific and region-specific data at municipality level. Firm-specific data was obtained from MMPartner, a Swedish firm that collects economic information on firms in Sweden. The data used here is from a dataset covering the annual reports of all limited firms that were tax-based in a specific municipality and active in the market during 1990-20001. The annual reports were originally submitted, as required by the law, to the Swedish patent and registration office (PRV). The dataset includes, among other items, measures of profit, number of employees, salaries, fixed costs, and liquidity. In order to include only active firms in the empirical analysis, the sample was restricted to firms with documented sales during the study period.

Municipality-specific data, including demographic measures, average income, political preferences, educational level, and unemployment, were provided by Statistics Sweden (SCB). Due to the division of some municipalities into smaller units during the study period, as well as the merger of three counties, 56 municipalities were omitted from the study, leaving 233.

Data concerning which firms received RIG during the study period was supplied by the Swedish Agency for Economic and Regional Growth (NUTEK). All data used, irrespective of original source, was collected and provided to the authors by the Swedish Institute for Growth Policy Studies (ITPS). The results have also been presented (in Swedish) previously in [10].

3.2. Propensity Score Matching

To test the effects of RIG on firm performance, we estimated the average effect on: 1) the number of employees, and 2) the return on equity2. The “treatment group” consists of firms that received RIG during the study period. Propensity-score matching was used to match “untreated” observations with “treated observations” if they had a similar probability, based on firm characteristics, of being treated (i.e., receiving a grant). To take account of time-invariant unobservable heterogeneity, a difference-in-difference propensity score matching-method was used. Thus, instead of studying numbers of employees and returns on equity directly, we focused on changes in those variables. If RIG were effective in promoting firm performance, we expect that firms receiving grants will have developed better after receiving grants than similar firms that did not receive grants. This method makes it possible to get an unbiased estimate of the treatment effect even if there were unobservable differences between firms that received RIG and other firms, as long as the differences were time-invariant.

Matching methods differ by how much weight is placed on the control observations. Nearest-neighbor matching was used here, putting all weight on the control (non-treated) observation with the most similar propensity score. This reduces bias, since only the best matches are used, but could lead to increased variance, compared to matching methods which use more control observations. We imposed a common support condition ofmaximum 0.00001 allowed distance between the propensity-score of the treated and the control. Treated observations for which no matches could be found within this distance were excluded.

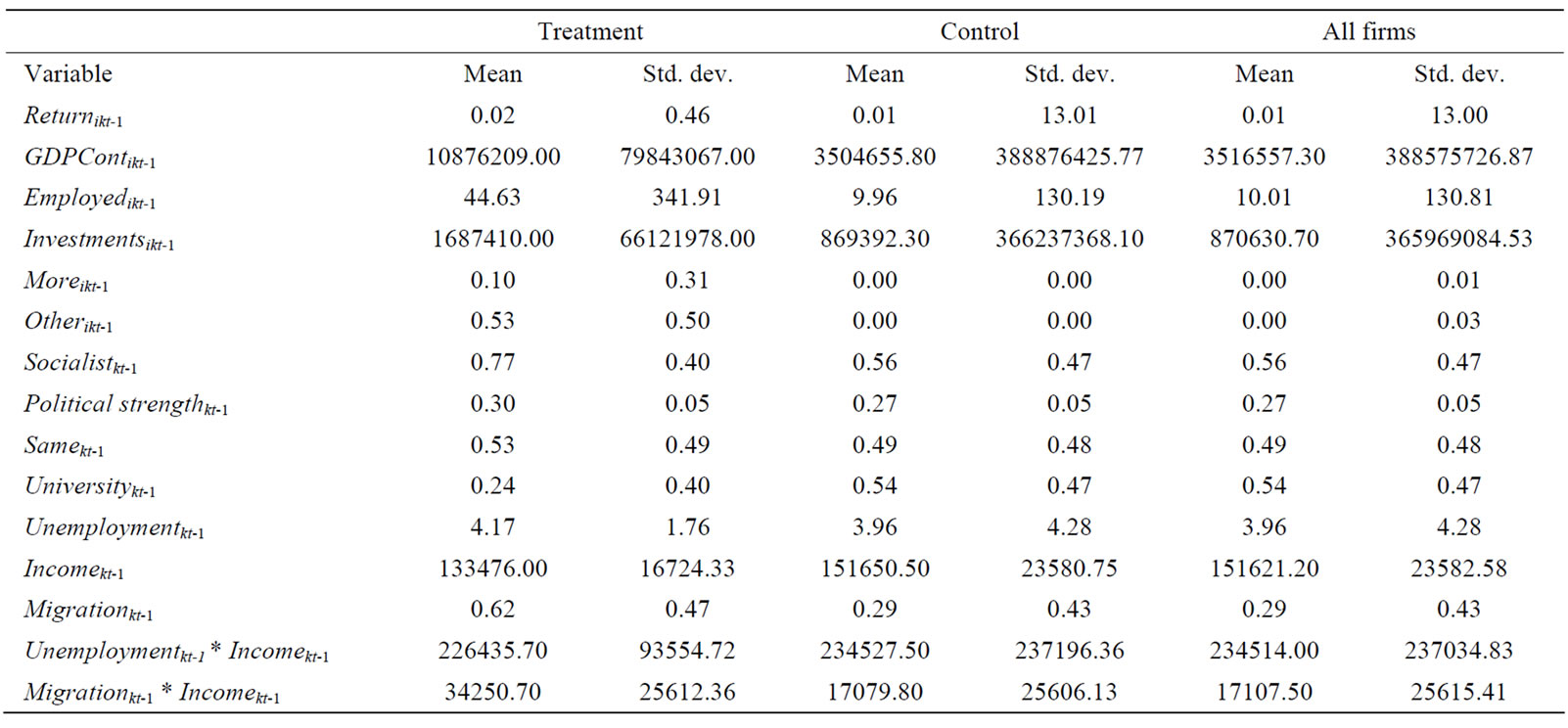

The final dataset contains 362,258 observations, of which 3,015 are from firms that received RIG. Table 1 reports means and standard deviations for the variables included in the analysis for the treatment groups, control group, and all firms. On average, firms that received RIG differed substantially from other firms, with more employees and higher returns on equity. As mentioned, this sample selection was controlled for by using propensityscore matching.

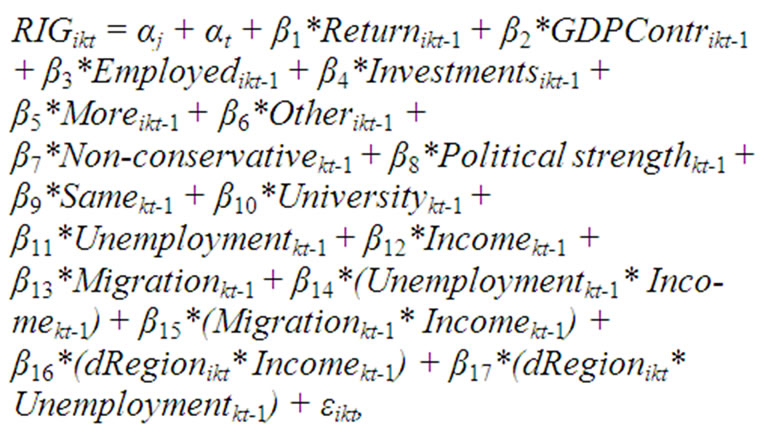

The first step in estimating the effects of RIG was thus to estimate propensity scores relating to the probability of belonging to the treatment group. Among a general set of models, the final specification was chosen using the Akaike consistent information criterion. As such, propensity scores were calculated using logit estimation of the equation

(1)

(1)

where αj and αt are region-specific and time-specific fixed effects; Returnikt-1 is the return on equity of firm i in municipality k in the previous year; GDPContrikt-1 is the direct contribution of the firm to GDP; Employedikt-1 is the number of employees of the firm; and Investmentsikt-1 is the size of the firm’s investments. Moreikt is then an indicator variable equal to one if the firm had more than one regional investment grant, and Otherikt is an indicator variable equal to one if the firm also received other types of regional grants (such as employment grants or transportation grants etc., described in Section 2).

Municipality-specific information was next included in the model: Non-conservativekt is an indicator variable equal to one if the municipality had a left-wing majority; Political strengthkt is a Herfindahl-index relating to the number of seats each party had in the local county council; and Samekt is an indicator variable equal to one if the political majority was the same in the municipality as at the national level. Universitykt is an indicator variable equal to one if the municipality had a university or university college; Unemploymentkt is the share of the municipal population unemployed; Incomekt measures average income in the municipality; and Migrationkt measures the inor outflow of people as a share of the municipal population.

Finally, since it is likely that there are interactions among some of the variables, the model also contains interaction-terms for Unemploymentkt* Incomekt, Migrationkt* Incomekt, dRegionikt* Incomekt, and dRegionikt* Unemploymentkt.

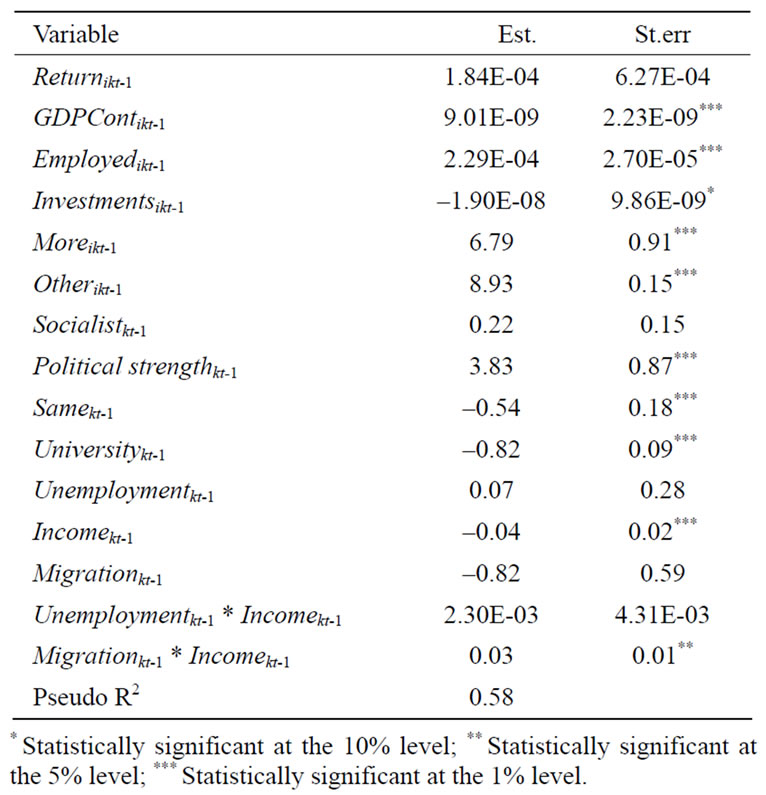

The results from logit estimation of (1) are presented in Table 2, where the regionand time-specific fixed effects, and the interactions including the region-specific fixed effects, have been excluded to save space.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics.

Table 2. Estimation results, probability of receiving regional investment grants, 1990-2000.

Firms with higher direct contribution to GDP and more employees had a higher probability of receiving a grant, as did those that had previously received either a regional investment grant or some other form of government grant. In addition, low investment in period t-1 increased the probability of receiving a grant. RIG were also more common in municipalities with strong political leadership (as measured by the Herfindahl index), no university or university college, and low average income.

The next step involved finding the best possible match in the control group for each “treated” firm, and comparing outcomes. It seems reasonable to believe, however, that RIG effects are not constant over time. We therefore divided the data into yearly sub-periods to test this possibility. Thus the logit equation used to find matches was also estimated for each year (results left out in order to save space).

3.3. Difference-in-Difference Estimates

There is also a question of the timing of grant effects, since some investments might take some time to complete, and effects on employment or returns on equity might not show up for even longer. Difference-in-difference estimates were thus calculated over one, three, and five years after the grant year.

Finally, there could also be a so-called threshold effect, if grants need to reach a certain size before having any measurable effect on employment or returns. Thus the analysis was also performed using only grants exceeding one hundred thousand SEK or exceeding one million SEK.

4. Regional Investment Grants and Firm Performance

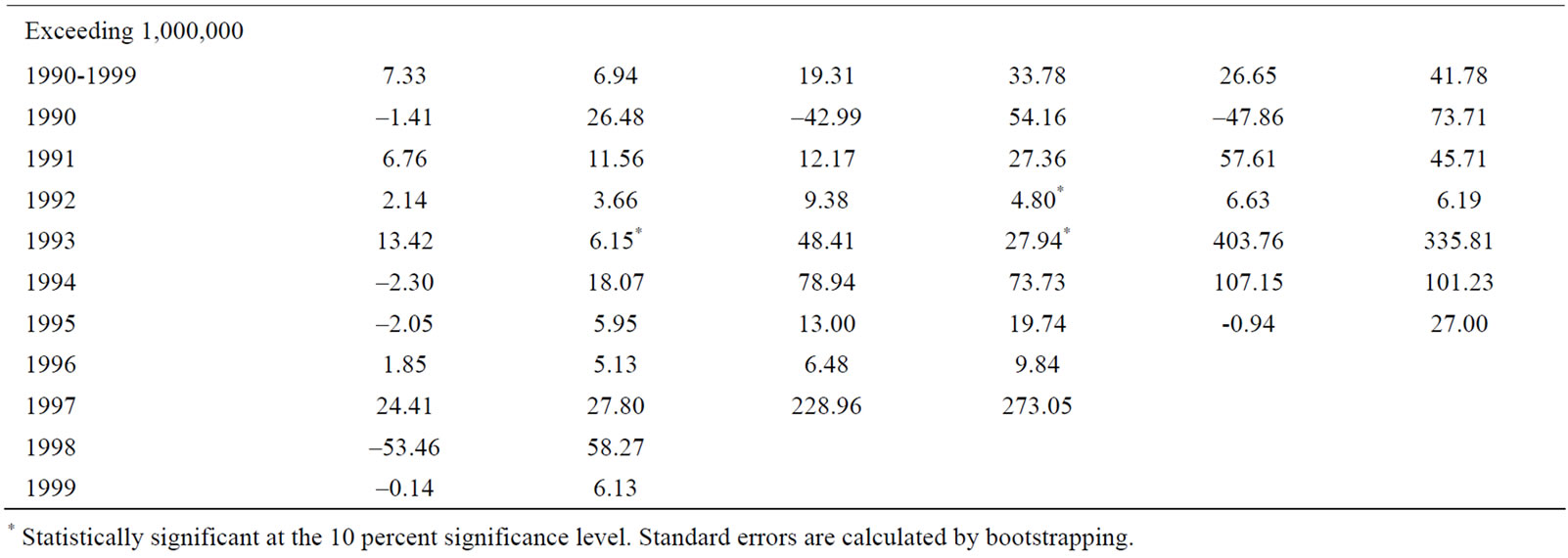

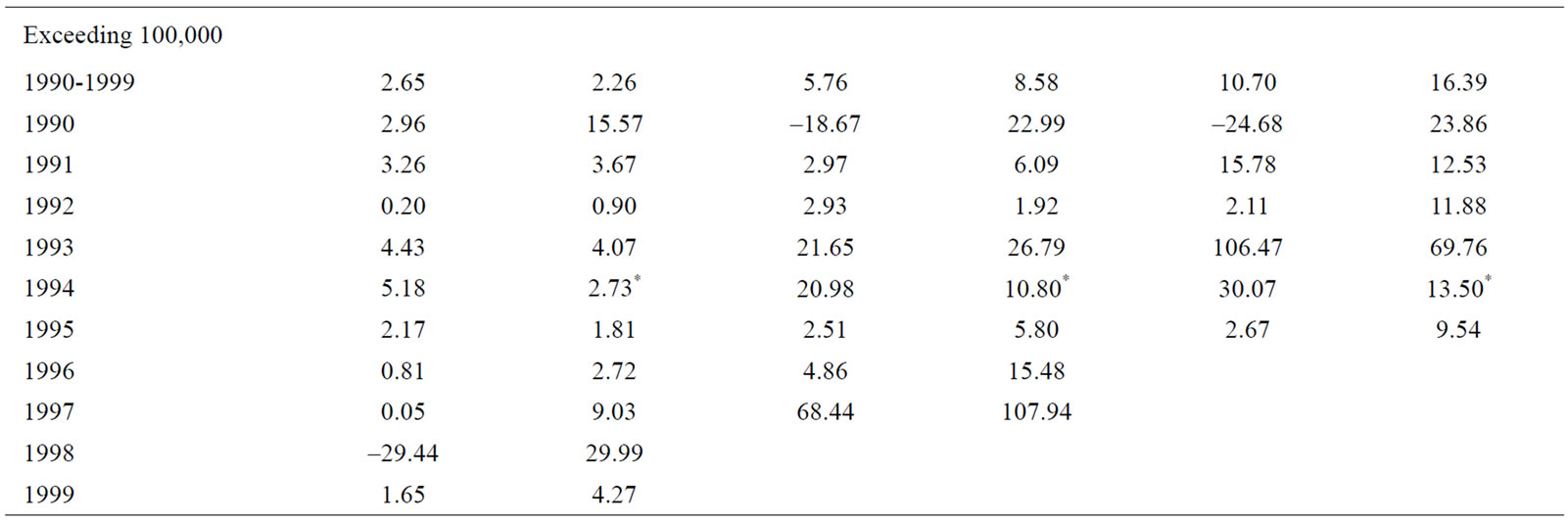

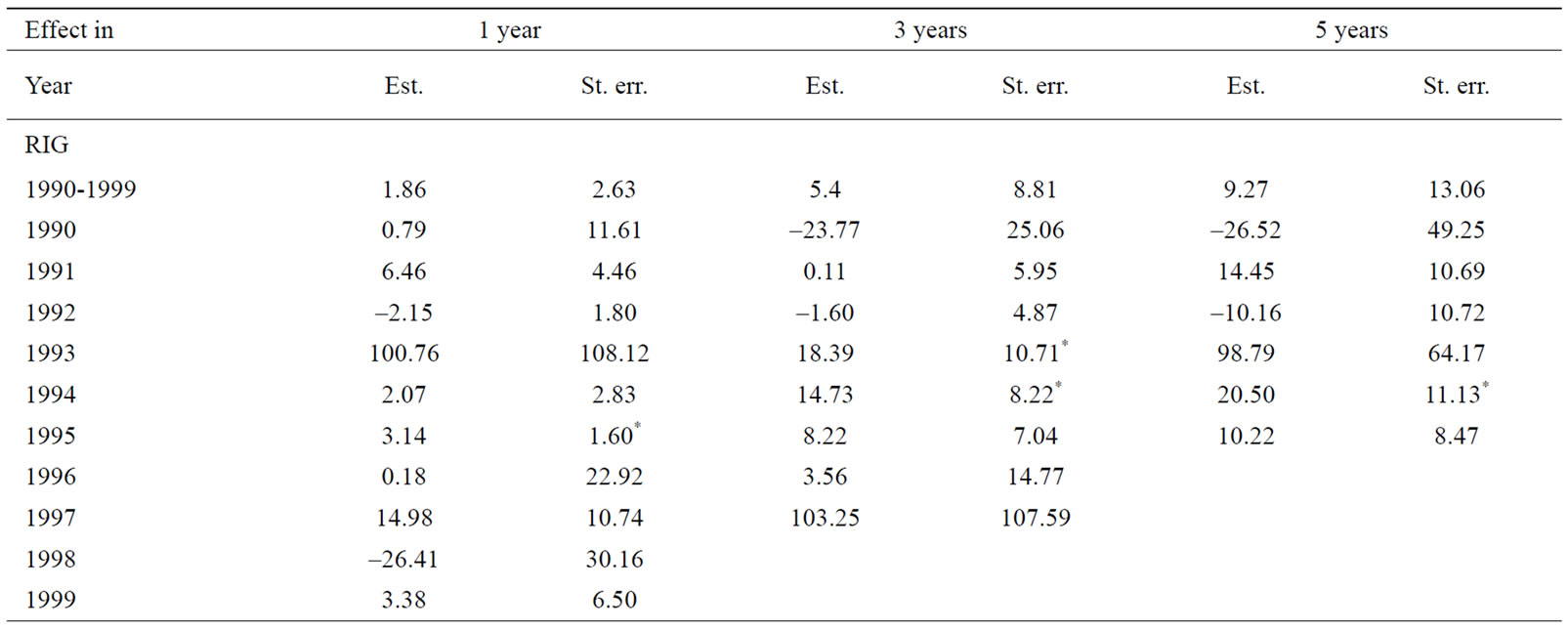

Yearly and overall difference-in-difference estimates of the effects of RIG on employment are presented (Table 3) for one-, three-, and five-year periods and for grants exceeding SEK 100,000 or SEK 1,000,000.

In most of the estimated models, no statistically significant effect on employment was found, indicating that, in general, recipient firms did not increase their number of employees more than similar firms that did not receive

Table 3. Difference-in-difference estimates, number of employees.

a grant. Hence, RIG do not seem to have been very successful in increasing employment during the study period.

However, there are a few exceptions. For grant of any size, there are positive and statistically significant effects after three years for 1993 and 1994 recipients; after 5 years for 1994 recipients; and after one year for 1995 recipients. Recipients in 1993, on average, employed 18 persons more during 1993-1996 than did firms not receiving a grant, and 15 persons more during 1994-1997. Recipients in 1994, on average, employed 20 more during 1994-1999 than did firms not receiving a grant. Recipients in 1995 also employed slightly more than others during that year. All these statistically significant results were in 1993 to 1995, i.e. during the end of the Swedish recession of the early 1990s, and this pattern holds for larger grants as well.

Recipients of over one hundred thousand SEK in 1994, on average, employed 5 more during that year, 21 more during 1994-1997, and 30 more during 1994-1999. Recipients of more than one million SEK in 1992 employed 9 more during 1992-1995, while recipients in 1993 employed 13 more during that year and 48 more during 1993-1996.

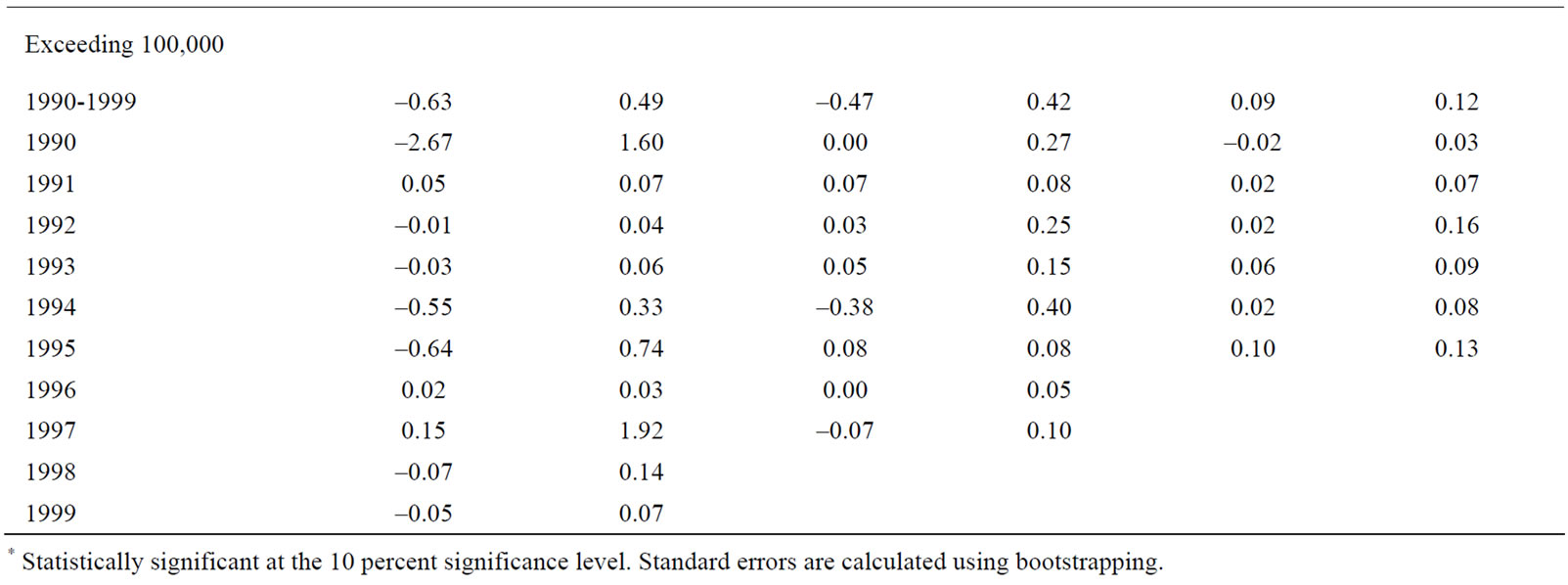

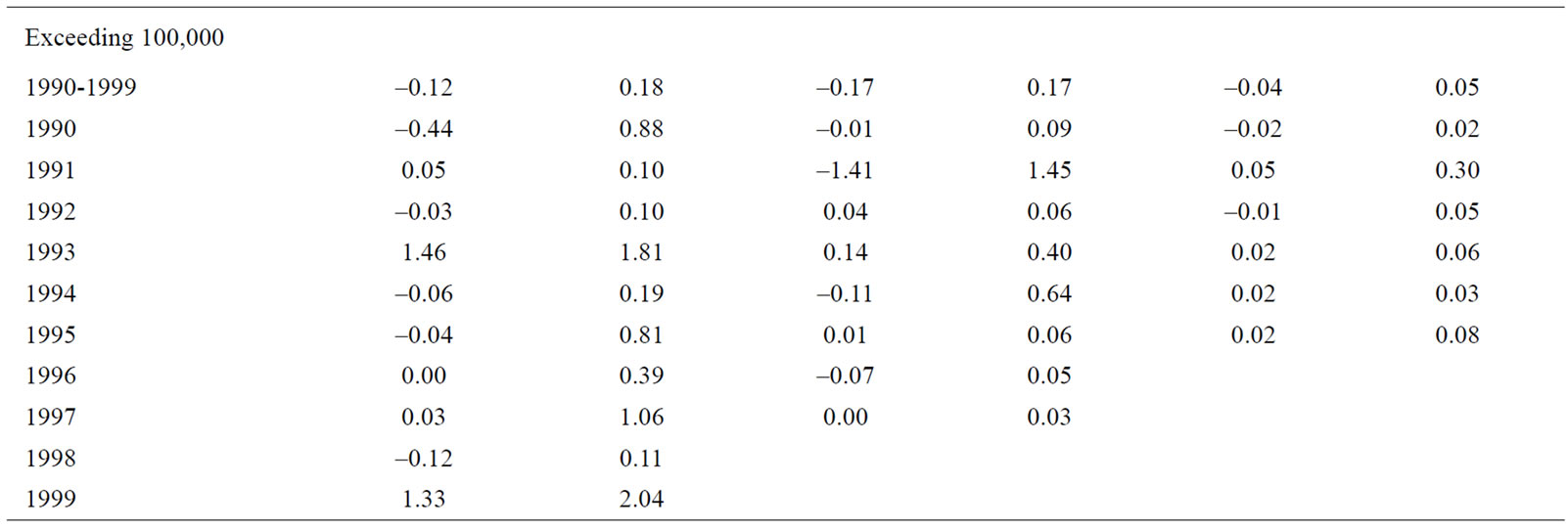

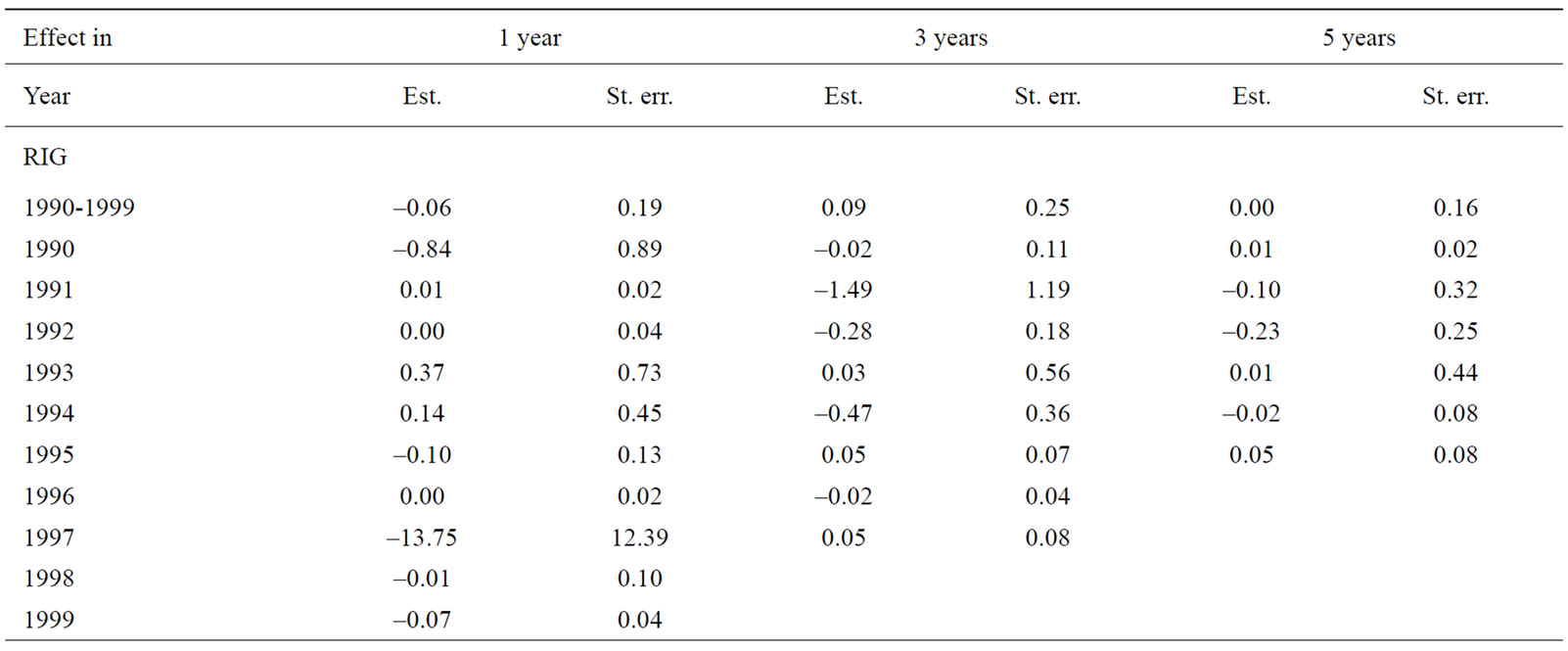

Similar estimates of effects on returns are presented in Table 4.

No statistically significant effects were found. Thus, recipient firms did not seem to perform better in terms of returns on equity than similar firms that did not receive a grant.

Table 4. Difference-in-difference estimates, the return on equity.

5. Conclusions

The aim of this paper has been to study whether regional investment grants targeted towards firms affect employment or owners’ returns on equity. To control for sample selection, we used propensity-score matching, whereby firms that received grants were compared to otherwise similar firms that received no grants during the study period.

Regional investment grants did not seem to have any impact on firm performance. Firms that received grants did not perform better in terms of returns on equity when compared to matched firms in the control group. In most years, recipient firms also did not hire more employees, and we thus conclude that, in general, RIG do not affect employment. The few exceptions during 1993-1995, were during the recovery from the early 1990s recession.

The results thus cast doubt on the use of regional investment grants as a general policy instrument to improve firm performance. An issue for future research is whether other types of regional grants may have been more successful, and whether the results are applicable to other outcome variables such as revenue growth, innovation, market capitalization, and the survival rate.

6. Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Swedish Institute for Growth Policy Studies (ITPS) for supplying the data used in this study. We also thank participants at a seminar at the Ratio Institute for valuable comments and suggestions.

7. References

[1] C. Wren, “Regional Grants. Are They Worth it?” Fiscal Studies, Vol. 26, No. 2, 2005, pp. 245-275.

[2] R. Harris, “Regional Economic Policy in Northern Ireland 1945-1988,” Avebury, Aldershot, 1991.

[3] R. Harris and M. Trainor, “Capital Subsidies and their Impact on Total Factor Productivity: Firm-Level Evidence from Northern Ireland,” Journal of Regional Science, Vol. 45, No. 1, 2005, pp. 49-74.

[4] R. Harris and M. Trainor, “Impact of Government Intervention on Employment Change and Plant Closure in Northern Ireland, 1983-97,” Regional Studies, Vol. 41, No. 1, 2007, pp. 51-63.

[5] D. Skuras, K. Tsekouras, E. Dimara and D. Tzelepis, “The Effects of Regional Capital Subsidies on Productivity Growth: A Case Study of the Greek Food and Beverage Manufacturing Industry,” Journal of Regional Science, Vol. 46, No. 2, 2006, pp. 355-381.

[6] R. Harris and C. Robinson, “Industrial Policy in Great Britain and its Effect on Total Factor Productivity in Manufacturing Plants, 1990-1998,” Scottish Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 51, No. 4, 2004, pp. 528-543.

[7] F. Bergström, “Capital Subsidies and the Performance of Firms,” Small Business Economics, Vol. 14, No. 3, 2000, pp. 183-193.

[8] J.-W. Lee, “Government Interventions and Productivity Growth,” Journal of Economic Growth, Vol. 1, No. 3, 1996, pp. 391-414.

[9] P. Rosenbaum and D. Rubin, “The Central Role of the Propensity Score in Observational Studies for Causal Effects,” Biometrica, Vol. 70, No. 1, 1991, pp. 41-55.

[10] M. Ankarhem, N. Rudholm and S. Quoreshi, “Effektutvärdering av det regional utvecklingsbidraget: En studie av effekter på svenska aktiebolag,” Rapport A2007:26, Institutet för Tillväxtpolitiska Studier (ITPS), Sweden, 2007.

NOTES

1This means that different types of limited companies are included in the dataset, e.g., both private and public companies. It is, however, unlikely that private companies will be matched with public companies when propensity score matching is used.

2Note that the choice of output variable (e.g., employment and returns on equity) can be challenged since they are subjective indicators.